Walther Funk

Walther Funk (18 August 1890 – 31 May 1960) was a German economist and Nazi official who served as Reich Minister for Economic Affairs from 1938 to 1945 and was tried and convicted as a major war criminal by the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. Sentenced to life in prison, he remained incarcerated until he was released on health grounds in 1957. He died three years later.

Walther Funk | |

|---|---|

Funk with Golden Party Badge, 1942 | |

| Reichsminister of Economics | |

| In office 5 February 1938 – 8 May 1945 | |

| President | Adolf Hitler |

| Chancellor | Adolf Hitler |

| Preceded by | Hermann Göring |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| President of the Reichsbank | |

| In office 19 January 1939 – 8 May 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Hjalmar Schacht |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Reich Press Chief and State Secretary in the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda | |

| In office 13 March 1933 – 26 November 1937 | |

| Appointed by | Adolf Hitler |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Otto Dietrich |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 August 1890 Danzkehmen, East Prussia, German Empire |

| Died | 31 May 1960 (aged 69) Düsseldorf, North Rhine-Westphalia, West Germany |

| Political party | Nazi Party |

| Spouse(s) | Luise Schmidt-Sieben |

| Profession | Economist |

Early life

Funk was born into a merchant family in 1890 in Danzkehmen (present-day Sosnowka in the Russian Kaliningrad Oblast) near Trakehnen in East Prussia. He was the only one of the Nuremberg defendants who was born in the former eastern territories of Germany. He was the son of Wiesenbaumeister Walther Funk the elder and his wife Sophie (née Urbschat). He studied law, economics, and philosophy at the Humboldt University of Berlin and the University of Leipzig. In World War I, he joined the infantry, but was wounded and subsequently discharged as medically unfit for service in 1916. Following the end of the war, he worked as a journalist, and in 1924 he became the editor of the centre-right financial newspaper the Berliner Börsenzeitung. In 1920, Funk married Luise Schmidt-Sieben.

Political life

Funk, who was a nationalist and anti-Marxist, resigned from the newspaper in the summer of 1931 and joined the Nazi Party, becoming close to Gregor Strasser, who arranged his first meeting with Adolf Hitler. Partially because of his interest in economic policy, he was elected a Reichstag deputy in July 1932, and within the party, he was made chairman of the Committee on Economic Policy in December 1932, a post that he did not hold for long. After the Nazi Party came to power, he stepped down from his Reichstag position and was made Chief Press Officer of the Third Reich, a post which involved censorship of anything deemed critical of Nazi policies. His boss was Joseph Goebbels.

Third Reich career

In March 1933, Funk was appointed as a State Secretary (Staatssekretär) at the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda (Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda).[1] In the summer of 1936 when Hitler commissioned Albert Speer for the rebuilding of central Berlin, it was Funk who proposed his new title of "Inspector-General of Buildings for the Renovation of the Federal Capital".[2] In 1938, Funk became Chief Plenipotentiary for Economics (Wirtschaftsbeauftragter), as well as Reich Minister of Economics (Reichswirtschaftsminister) replacing Hjalmar Schacht, who had resigned on 26 November 1937. Schacht had been engaged in a power struggle with Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, who wanted to tie the ministry more closely to his Four Year Plan Office.[3]

Between April 1938-March 1939 Funk was also a Director of the Swiss-based multi-national Bank of International Settlements,[4] and in January 1939, Hitler appointed Funk as President of the Reichsbank. Funk recorded that by 1938 the German state had confiscated Jewish property worth two million marks, using decrees from Hitler and other top Nazis to force German Jews to leave their property and assets to the State if they emigrated, such as the Reich Flight Tax.

Funk was present at a great many important meetings, including that held in the Great Hall of the [still extant] Air Ministry on 13 February 1942 chaired by Field-Marshall Erhard Milch about the four year plan, which embraced the entire economy. 30 crucial people were present. Funk sat to the right of Milch, at his request. After much debate Albert Vogler said "there must be one man able to make decisions. Industry did not care who it was." After further discussion Funk stood up and nominated Milch as that man. Speer whispered to Milch this was not a good idea and Milch declined. Five days later Hitler conferred the role on Speer. As he and Funk walked Hitler back to his apartment in the Chancery Funk promised Speer that he would place everything at his disposal and do all in his power to help him. Speer relates that Funk "kept the promise, with minor exceptions."[5] Funk was appointed to the Central Planning Board in September 1943 and subsequently joined Robert Ley, Speer and Goebbels in the struggle against the influence on Hitler by Martin Bormann.[6] Funk and Milch were again together for Goering's birthday party on 12 January 1944 when Funk, as he did every year, delivered the birthday speech at the banquet.[7]

Nuremberg

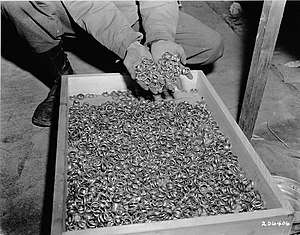

Funk was tried with other Nazi leaders at the Nuremberg trials. He was accused by Allied prosecutors of having been closely involved in the State confiscation and disposal of the property of German Jews; and of conspiracy to commit crimes against peace; planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression; war crimes and crimes against humanity. He argued that, despite his employment titles, he had very little power in the regime. He did however, admit to signing the laws that "aryanized" Jewish property and in that respect claimed to be "morally guilty". At the Nuremberg trials American Chief Prosecutor Robert Jackson labeled Funk as "The Banker of Gold Teeth", referring to the practice of extracting gold teeth from Nazi concentration camp victims, and forwarding the teeth to the Reichsbank for melting down to yield bullion. Many other gold items were stolen from victims, such as jewellery, eyeglasses and finger rings. Other items stolen from the victims included their clothing, furniture, artwork and paintings, as well as any wealth in stocks, shares, businesses and companies. Such business assets were taken by aryanization with often large and profitable businesses sold for less than their true worth. The monetary proceeds of auctions of such assets as furniture were passed to the Reichsbank in Max Heiliger accounts for use by the Nazi state or the SS. Even the hair of the victims was taken by shaving either just before or just after their murder. When clothing was distributed after the victims were shot by the Einsatzgruppen, blood stains were often visible at and near the bullet holes.[8]

Funk was clearly distressed during the proceedings and cried during presentation of evidence such as the murders carried out in the Nazi concentration camps, and needed sleeping pills at night. Hjalmar Schacht relates that he, Funk and von Papen formed a close intimate circle at Nuremburg. He felt Funk was unable to comprehend the serious nature of the duties which he had undertaken. Schacht believed that there were many matters of which Funk had no knowledge whatsoever and that he gave a poor performance in the witness-box.[9] However Albert Speer gave a different version of events. He said that when he first came into contact with Funk at Nuremberg "he looked extremely worn and downcast." But "Funk reasoned skillfully and in a way that stirred my pity" in the witness box.[10]

Göring meanwhile described Funk as "an insignificant subordinate", but documentary evidence and his wartime biography Walther Funk, A Life for the Economy were used against him during the trial, leading to his conviction on counts 2, 3 and 4 of the indictment and his sentence of life imprisonment.

Funk was held at Spandau Prison along with other senior Nazis. He was released on 16 May 1957 because of ill health. He made a last-minute call on Rudolf Hess, Albert Speer and Baldur von Schirach before leaving the prison.[11] He died three years later in Düsseldorf of diabetes.

Culture

Schacht, who knew Funk well, said he was "extraordinarily musical" being "a first-rate connoisseur of music whose personal preferences in life were decidedly for the artistic and literary." At a dinner when he sat next to Funk, the orchestra played a melody by Franz Lehar. Funk remarked "ah! Lehár - the Fuhrer is particularly fond of his music." Schacht replied, jokingly, "its a pity that Lehár is married to a Jewess" to which Funk immediately responded "that's something the Fuhrer must not know on any account![12] Speer relates how Hitler played for him a record of Liszt's Les Préludes and said "this is going to be our victory fanfare for the Russian campaign. Funk chose it!"[13]

See also

- Auschwitz concentration camp

- Nazi plunder

- Oskar Groening

- Max Heiliger

References

- ''Memoirs by Franz von Papen, London, 1952, p.312.

- Inside the Third Reich by Albert Speer, London, 1970, p.76.

- My First Seventy-Six Years, by Hjalmar Schacht, London 1955, p.377. Online

- Bank of International Settlements, "Ninth Annual Report: 1 April 1938 – 31 March 1939" p. 135-7

- Speer, 1970, pps:200-202.

- Speer, 1970, p.263.

- Speer, 1970, p.322.

- Nuremberg: Tyranny on Trial. History Channel. 1995. Television:- Not a reliable source.

- Schacht, 1955, p.455-6.

- Speer, 1970, pps:508 & 515.

- Bird, Eugene (1974). The Loneliest Man in the World. London: Secker & Warburg. p. 121. ISBN 0436042908.

- Schacht, 1955, pps:340-1 and 456.

- Speer, 1970, p.180.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Walther Funk |

- Works by or about Walther Funk at Internet Archive

- Lived in the historic villa at Sven-Hedin-Str. 11

- Funk war crimes dossier

- Newspaper clippings about Walther Funk in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Interrogation of Funk, Walther / Office of U.S. Chief of Counsel for the Prosecution of Axis Criminality / Interrogation Division Summary

_(14342874343).jpg)