Wilhelm Keitel

Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel (22 September 1882 – 16 October 1946) was a German field marshal and war criminal during the Nazi era who served as Chief of the Armed Forces High Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, OKW) during World War II. In this capacity, Keitel signed a number of criminal orders and directives that led to a war of unprecedented brutality and criminality.

Wilhelm Keitel | |

|---|---|

Keitel as field marshal in 1942 | |

| Chief of Armed Forces High Command | |

| In office 4 February 1938 – 8 May 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Werner von Blomberg (as Reich Minister of War) |

| Succeeded by | None (position abolished) |

| Head of Armed Forces Office in Reich Ministry of War | |

| In office 1 October 1935 – 4 February 1938 | |

| Preceded by | Walter von Reichenau |

| Succeeded by | None (position abolished) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel 22 September 1882 Helmscherode, Duchy of Brunswick, German Empire |

| Died | 16 October 1946 (aged 64) Nuremberg, Allied-occupied Germany |

| Cause of death | Execution |

| Spouse(s) | Lisa Fontaine ( m. 1909) |

| Relatives | Bodewin Keitel (brother) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) | "Lakeitel" |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | German Army |

| Years of service | 1901–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Oberkommando der Wehrmacht |

| Battles/wars | World War I

World War II |

| Awards | Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross |

| Criminal conviction | |

| Known for | War crimes of the Wehrmacht |

| Conviction(s) | Crimes against humanity Crimes against peace Criminal conspiracy War crimes |

| Trial | Nuremberg trials |

| Criminal penalty | Death penalty |

Keitel's rise to the Wehrmacht high command began with his appointment as the head of the Armed Forces Office at the Reich Ministry of War in 1935. After Hitler took command of the Wehrmacht in 1938, he replaced the ministry with the OKW, with Keitel as its chief. Keitel was reviled among his military colleagues as Hitler's habitual "yes-man".

After the war, Keitel was indicted by the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg as one of the "major war criminals". He was found guilty on all counts of the indictment: crimes against humanity, crimes against peace, criminal conspiracy, and war crimes. Keitel was sentenced to death and executed by hanging in 1946.

Early life and pre-Wehrmacht career

Keitel was born in the village of Helmscherode near Gandersheim in the Duchy of Brunswick, Germany. The eldest son of Carl Keitel (1854–1934), a middle-class landowner, and his wife Apollonia Vissering (1855–1888), he planned to take over his family's estates after completing his education at a gymnasium but this foundered on his father's resistance. Instead, he embarked on a military career in 1901, becoming an officer cadet of the Prussian Army. As a commoner, he did not join the cavalry, but a field artillery regiment in Wolfenbüttel, serving as adjutant from 1908.[1] On 18 April 1909, Keitel married Lisa Fontaine, a wealthy landowner's daughter at Wülfel near Hanover.[2]

During World War I, Keitel served on the Western Front and took part in the fighting in Flanders, where he was severely wounded.[3] After being promoted to captain, Keitel was then posted to the staff of an infantry division in 1915.[4] After the war, Keitel was retained in the newly created Reichswehr of the Weimar Republic and played a part in organizing the paramilitary Freikorps units on the Polish border. In 1924, Keitel was transferred to the Ministry of the Reichswehr in Berlin, serving with the Truppenamt ('Troop Office'), the post-Versailles disguised German General Staff. Three years later, he returned to field command.[3]

Now a lieutenant-colonel, Keitel was again assigned to the Ministry of War in 1929 and was soon promoted to Head of the Organizational Department ("T-2"), a post he held until Adolf Hitler took power in 1933. Playing a vital role in the German re-armament, he traveled at least once to the Soviet Union to inspect secret Reichswehr training camps. In the autumn of 1932, he suffered a heart attack and double pneumonia.[5] Shortly after his recovery, in October 1933, Keitel was appointed as deputy commander of the 3rd Infantry Division; in 1934, he was given command of the 22nd Infantry Division at Bremen.[6]

Rise to the Wehrmacht High Command

In 1935, at the recommendation of General Werner von Fritsch, Keitel was promoted to the rank of major general and appointed chief of the Reich Ministry of War's Armed Forces Office (Wehrmachtsamt), which oversaw the army, navy, and air force.[7][8] After assuming office, Keitel was promoted to lieutenant general on 1 January 1936.[9]

On 21 January 1938, Keitel received evidence revealing that the wife of his superior, War Minister Werner von Blomberg, was a former prostitute.[10] Upon reviewing this information, Keitel suggested that the dossier be forwarded to Hitler's deputy, Hermann Göring, who used it to bring about Blomberg's resignation.[11]

Hitler took command of the Wehrmacht in 1938 and replaced the War Ministry with the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht), with Keitel as its chief.[12] As a result of his appointment, Keitel assumed the responsibilities of Germany's War Minister.[13] Soon after his promotion, Keitel convinced Hitler to appoint Walther von Brauchitsch as Commander-in-Chief of the Army, replacing von Fritsch.[14] He became a full general in November 1938.[15]

World War II

Field Marshal Ewald von Kleist labelled Keitel nothing more than a "stupid follower of Hitler" because of his servile "yes man" attitude with regard to Hitler. His sycophancy was well known in the army, and he acquired the nickname 'Lakeitel', a pun derived from Lakai ("lackey") and his surname.[16][17] Hermann Göring's description of Keitel as having "a sergeant's mind inside a field marshal's body" was a feeling often expressed by his peers. He had been promoted because of his willingness to function as Hitler's mouthpiece.[18]

Keitel was predisposed to manipulation because of his limited intellect and nervous disposition; Hitler valued his hard work and obedience.[19] On one occasion, Burkhart Müller-Hillebrand asked who Keitel was: upon finding out he became horrified at his own failure to salute his superior. Franz Halder, however, told him: "Don't worry, it's only Keitel".[19] German officers consistently bypassed him and went directly to Hitler.[15]

After Germany defeated France in the Battle of France in six weeks, Keitel described Hitler as “the greatest warlord of all time”.[20]

The planning for Operation Barbarossa, the 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union, was begun tentatively by Halder with the redeployment of the 18th Army into an offensive position against the Soviet Union.[21] On 31 July 1940, Hitler held a major conference that included Keitel, Halder, Alfred Jodl, Erich Raeder, Brauchitsch and Hans Jeschonnek which further discussed the invasion. The participants did not object to the invasion.[22] Hitler asked for war studies to be completed[23] and Georg Thomas was given the task of completing two studies on economic matters. The first study by Thomas detailed serious problems with fuelling and rubber supplies. Keitel bluntly dismissed the problems, telling Thomas that Hitler would not want to see it. This influenced Thomas' second study which offered a glowing recommendation for the invasion based upon fabricated economic benefits.[24]

Keitel played an important role after the failed 20 July plot in 1944. He sat on the Army "court of honour" that handed over many officers who were involved, including Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben, to Roland Freisler's notorious People's Court. Around 7,000 people were arrested, many of whom were tortured by the Gestapo, and around 5,000 were executed.[25]

In April and May 1945, during the Battle of Berlin, Keitel called for counterattacks to drive back the Soviet forces and relieve Berlin. However, there were insufficient German forces to carry out such counterattacks. After Hitler's suicide on 30 April, Keitel stayed on as a member of the short-lived Flensburg government under Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz. Upon arriving in Flensburg, Albert Speer, the Minister of Armaments and War Production, said that Keitel grovelled to Dönitz in the same way as he had done to Hitler. On 7 May 1945, Alfred Jodl, on behalf of Dönitz, signed Germany's unconditional surrender on all fronts. Joseph Stalin considered this an affront, so a second signing was arranged at the Berlin suburb of Karlshorst 8 May. There, Keitel signed the German surrender to the Soviet Union. Five days later he was arrested along with the rest of the Flensburg Government, at the request of the U.S.[26]

Role in crimes of the Wehrmacht and the Holocaust

Keitel had full knowledge of the criminal nature of the planning and the subsequent Invasion of Poland, agreeing to its aims in principle.[27] The Nazi plans included mass arrests, population transfers and mass murder. Keitel did not contest the regime's assault upon basic human rights or counter the role of the Einsatzgruppen in the murders.[27] The criminal nature of the invasion was now obvious; local commanders continued to express shock and protest over the events they were witnessing.[28] Keitel continued to ignore the protests among the officer corps while they became morally numbed to the atrocities.[27]

Keitel issued a series of criminal orders from April 1941.[29] The orders went beyond established codes of conduct for the military and broadly allowed the execution of Jews, civilians and non-combatants for any reason. Those carrying out the murders were exempted from court-martial or later being tried for war crimes. The orders were signed by Keitel, however, other members of the OKW and the OKH, including Halder, wrote or changed the wording of his orders. Commanders in the field interpreted and carried out the orders.[30]

In the summer and autumn of 1941, German military lawyers unsuccessfully argued that Soviet prisoners of war should be treated in accordance with the Geneva Convention. Keitel rebuffed them, writing: "These doubts correspond to military ideas about wars of chivalry. Our job is to suppress a way of life."[31] In September 1941, concerned that some field commanders on the Eastern Front did not exhibit sufficient harshness in implementing the May 1941 order on the "Guidelines for the Conduct of the Troops in Russia", Keitel issued a new order, writing: "[The] struggle against Bolshevism demands ruthless and energetic action especially also against the Jews, the main carriers of Bolshevism".[32] Also in September, Keitel issued an order to all commanders, not just those in the occupied Soviet Union, instructing them to use "unusual severity" to stamp out resistance. In this context, the guideline stated that execution of 50 to 100 "Communists" was an appropriate response to a loss of a German soldier.[32] Such orders and directives further radicalised the army's occupational policies and enmeshed it in the genocide of the Jews.[33]

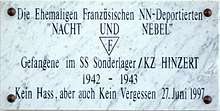

In December 1941, Hitler instructed the OKW to subject, with the exception of Denmark, Western Europe (which was under military occupation) to the Night and Fog Decree.[34] Signed by Keitel,[35] the decree made it possible for foreign nationals to be transferred to Germany for trial by special courts, or simply handed to the Gestapo for deportation to concentration camps. The OKW further imposed a blackout on any information concerning the fate of the accused. At the same time, Keitel increased pressure on Otto von Stülpnagel, the military commander in France, for a more ruthless reprisal policy in the country.[34] In October 1942, Keitel signed the Commando Order that authorized the killing of enemy special operations troops even when captured in uniform.[36]

In the spring and summer of 1942, as the deportations of the Jews to extermination camps progressed, the military initially protested when it came to the Jews that laboured for the benefit of the Wehrmacht. The army lost control over the matter when the SS assumed command of all Jewish forced labour in July 1942. Keitel formally endorsed the state of affairs in September, reiterating for the armed forces that "evacuation of the Jews must be carried out thoroughly and its consequences endured, despite any trouble it may cause over the next three or four months".[37]

Trial, conviction, and execution

After the war, Keitel faced the International Military Tribunal (IMT), which indicted him on all four counts before it: conspiracy to commit crimes against peace, planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression, war crimes and crimes against humanity. Most of the case against him was based on his signature being present on dozens of orders that called for soldiers and political prisoners to be killed or 'disappeared'.[38] In court, Keitel admitted that he knew many of Hitler's orders were illegal.[39] His defence relied almost entirely on the argument he was merely following orders in conformity to "the leader principle" (Führerprinzip) and his personal oath of loyalty to Hitler.[18]

The IMT rejected this defence and convicted him on all charges. Although the tribunal's charter allowed "superior orders" to be considered a mitigating factor, it found Keitel's crimes were so egregious that "there is nothing in mitigation". In its judgment against him, the IMT wrote, "Superior orders, even to a soldier, cannot be considered in mitigation where crimes as shocking and extensive have been committed consciously, ruthlessly and without military excuse or justification." It was also pointed out that while he claimed the Commando Order, which ordered Allied commandos to be shot without trial, was illegal, he had reaffirmed it and extended its application. It also noted several instances where he issued illegal orders on his own authority.[38]

In his statement before the Tribunal, Keitel said: "As these atrocities developed, one from the other, step by step, and without any foreknowledge of the consequences, destiny took its tragic course, with its fateful consequences."[40] To underscore the criminal rather than military nature of Keitel's acts, the Allies denied his request to be shot by firing squad. Instead, he was executed at Nuremberg Prison by hanging.[41]

Keitel was executed by American Army Sergeant John C. Woods.[42] His last words were: "I call on God Almighty to have mercy on the German people. More than 2 million German soldiers went to their death for the fatherland before me. I follow now my sons – all for Germany."[43] The trap door was small, causing head injuries to Keitel and several other condemned men as they dropped.[44] Many of the executed Nazis fell from the gallows with insufficient force to snap their necks, resulting in a suffocating death struggle that in Keitel's case lasted 24 minutes.[42] The corpses of Keitel and the other nine executed men were, like Hermann Göring's, cremated at Ostfriedhof (Munich) and the ashes were scattered in the river Isar.[39]

Memoirs

Before his execution, Keitel published his memoirs which were titled in English as In the Service of the Reich. It was later re-edited as The Memoirs of Field-Marshal Keitel by Walter Görlitz ISBN 978-0-8154-1072-0. Another work by Keitel later published in English was named Questionnaire on the Ardennes offensive.[45]

See also

- . 8 May 1945 – via Wikisource.

References

Notes

- Mitcham & Mueller 2012, p. 1.

- Goerlitz 2003, p. 140.

- Mitcham & Mueller 2012, p. 2.

- Goerlitz 2003, pp. 140–141.

- Mitcham & Mueller 2012, pp. 2–3.

- Mitcham Jr. 2001, pp. 163–164.

- Wheeler-Bennett 1980, pp. 372–74.

- Hildebrand 1986, p. 45.

- Mitcham Jr. 2001, p. 164.

- Mitcham Jr. 2001, p. 8.

- Shirer 1990, p. 313.

- Megargee 2000, pp. 41–44.

- Megargee 2000, pp. 44–45.

- Megargee 2000, p. 42.

- Tucker 2005, p. 691.

- Stahel 2009, p. 277.

- Kane 2004, p. 708.

- Walker 2006, p. 85.

- Shepherd 2016, p. 29.

- Kershaw 2001, p. 300.

- Stahel 2009, p. 34.

- Stahel 2009, pp. 37–39.

- Stahel 2009, p. 85.

- Stahel 2009, p. 86.

- Tucker 2005, p. 681.

- Knopp 2001, p. 135.

- Browning 2004, p. 20.

- Browning 2004, p. 79.

- Heer et al. 2008, p. 17.

- Heer et al. 2008, pp. 17–20.

- Mazower 2008, p. 160.

- Förster 1998, p. 276.

- Shepherd 2016, p. 171.

- Shepherd 2016, pp. 193–194.

- Editorial staff n.d.

- USHMM n.d.

- Shepherd 2016, p. 304.

- de Vabres 2008.

- Darnstädt 2005.

- Conot 2000, p. 356.

- Wilkes, Jr. 2002.

- Zeller Jr. 2007.

- Smith 1946.

- Piper 2007.

- Keitel 1949.

Bibliography

- Browning, Christopher (2004). The Origins of the Final Solution. University of Nebraska Press and Yad Vashem. ISBN 0-8032-1327-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burleigh, Michael (2010). Moral Combat: Good and Evil in World War II. New York and London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-719576-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Conot, Robert E. (2000) [1947]. Justice at Nuremberg. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-88184-032-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Darnstädt, Thomas (4 April 2005). "EinGlücksfall der Geschichte". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 15 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de Vabres, M. (2008). "Judgement:Keitel". The Avalon Project. Lillian Goldman Law Library. Retrieved 11 November 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Editorial staff (n.d.). "Night and Fog Decree". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Förster, Jürgen (1998). "Complicity or Entanglement? The Wehrmacht, the War and the Holocaust (pages 266–283)". In Michael Berenbaum & Abraham Peck (ed.). The Holocaust and History The Known, the Unknown, the Disputed and the Reexamiend. Bloomington: Indian University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33374-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goerlitz, Walter (2003). "Keitel, Jodl, and Warlimont". In Barnett, Correlli (ed.). Hitler's Generals. Grove Press. pp. 139–175. ISBN 978-0802139948.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heer, Hannes; Manoschek, Walter; Pollak, Alexander; Wodak, Ruth (2008). The Discursive Construction of History: Remembering the Wehrmacht's War of Annihilation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230013230.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hildebrand, Klaus (1986). The Third Reich. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-04-9430327.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kane, Thomas M. (2004). "Keitel, Wilhelm". In Bradford, James C. (ed.). International Encyclopedia of Military History. Routledge. pp. 707–708. ISBN 978-1-135-95034-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keitel, Wilhelm (1949). Questionnaire on the Ardennes offensive. Historical Division, Headquarters, United States Army, Europe. ASIN B0007K46NA.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kershaw, Ian (2001). Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis. Penguin. ISBN 978-0140272390.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knopp, Guido (2001) [1998]. Hitlers Krieger [Hitler's Warriors] (in Swedish). Translated by Irheden, Ulf. Leipzig: Goldmann Verlag. ISBN 91-89442-17-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mazower, Mark (2008). Hitler's Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 9780713996814.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Megargee, Geoffrey (2006). War of Annihilation. Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front, 1941. Rowman & Littelefield. ISBN 0-7425-4481-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Megargee, Geoffrey P. (2000). Inside Hitler's High Command. Lawrence, Kansas: Kansas University Press. ISBN 0-7006-1015-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitcham, Samuel; Mueller, Gene (2012). Hitler's Commanders: Officers of the Wehrmacht, the Luftwaffe, the Kriegsmarine, and the Waffen-SS. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-44221-153-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitcham Jr., Samuel W. (2001). Hitler's Field Marshals and Their Battles. New York City, New York: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1130-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mueller, Gene (1979). The Forgotten Field Marshal: Wilhelm Keitel. Durham, NC: Moore Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87716-105-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Piper, Ernst (16 January 2007). "Der Tod durch den Strick dauerte 15 Minuten". Spiegel Online (in German). Der Spiegel. Retrieved 17 November 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stahel, David (2009). Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76847-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shepherd, Ben (2016). Hitler's Soldiers: The German Army in the Third Reich. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300179033.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shirer, William L. (1990). Rise And Fall Of The Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-72868-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Kingsbury (16 October 1946). "The Execution of Nazi War Criminals". Nuremberg Gaol, Germany. International News Service. Retrieved 17 November 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tucker, Spencer (2005). World War II: A Student Encyclopedia. ABC Clio. ISBN 1-85109-857-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- USHMM (n.d.). "Wilhelm Keitel: Biography". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 6 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walker, Andrew (2006). The Nazi War Trials. CPD Ltd. ISBN 978-1-903047-50-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilkes, Jr., Donald E. (2002). ""The Trial of the Century – and of all time". Part two". Popular Media. University of Georgia School of Law. 33. Retrieved 17 November 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wheeler-Bennett, John W. (1980) [1953]. Nemesis of Power: The German Army in Politics 1918–1945. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-06864-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zeller Jr., Tom (17 January 2007). "The Nuremberg Hangings — Not So Smooth Either". New York Times. Retrieved 15 October 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Volume 2, Chapter XV, Part 3: The Reich Cabinet" (PDF). Office of United States Chief of Counsel For Prosecution of Axis Criminality. 1946. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- Wilhelm Keitel in the German National Library catalogue