Working Group (resistance organization)

The Working Group (Slovak: Pracovná Skupina)[lower-alpha 1] was an underground Jewish organization in the Axis-aligned Slovak State during World War II. Led by Gisi Fleischmann and Rabbi Michael Dov Weissmandl, the Working Group rescued Jews from the Holocaust by gathering and disseminating information on the Holocaust in Poland, bribing and negotiating with German and Slovak officials, and smuggling valuables to Jews deported to Poland.

Pracovná Skupina[lower-alpha 1] | |

.jpg) Memorial to the Working Group in Bratislava[lower-alpha 2] | |

| Founded | Summer 1941 |

|---|---|

| Extinction | 28 September 1944 |

| Purpose | To save European Jews, especially Slovak Jews, from being murdered in the Holocaust |

| Location |

|

| Leader | Gisi Fleischmann |

Deputy | Michael Dov Weissmandl |

Treasurer | Wilhelm Fürst |

Other members | Oskar Neumann, Tibor Kováč, Armin Frieder, Andrej Steiner |

In 1940, SS official Dieter Wisliceny forced the Slovak Jewish community to set up the Jewish Center (ÚŽ) to implement anti-Jewish decrees. Members of the ÚŽ unhappy with collaborationist colleagues began to meet in the summer of 1941. In 1942, the group worked to prevent the deportation of Slovak Jews by bribing Wisliceny and Slovak officials, lobbying the Catholic Church to intervene, and encouraging Jews to flee to Hungary. Its efforts were mostly unsuccessful, and two-thirds of Slovakia's Jews were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp and camps and ghettos in the Lublin Reservation. Initially unaware of the Nazi plan to murder all Jews, the Working Group sent relief to Slovak Jews imprisoned in Lublin ghettos and helped more than two thousand Polish Jews flee to relative safety in Hungary during Operation Reinhard. The group transmitted reports of systematic murder received from the couriers and Jewish escapees to Jewish organizations in Switzerland and the Aid and Rescue Committee in Budapest.

After transports from Slovakia were halted in October 1942, the Working Group tried to bribe Heinrich Himmler through Wisliency into halting the deportation of European Jews to Poland (the Europa Plan). Wisliceny demanded a $3 million bribe, which far exceeded the Working Group's ability to pay, and broke off negotiations in September 1943. In April and May 1944, the Working Group collected and disseminated the Vrba–Wetzler report by two Auschwitz escapees documenting the murder of hundreds of thousands of Jews. By stimulating diplomatic pressure against the Hungarian government, the report was a major factor in regent Miklós Horthy's decision to halt the deportation of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz in July. After the Slovak National Uprising in fall 1944, the Germans invaded Slovakia and the Working Group attempted to bribe the Germans into sparing the Slovak Jews. Its failure to clearly warn Jews to go into hiding is considered its greatest mistake.

Most historians agree that the actions of the Working Group had some effect in halting the deportations from Slovakia between 1942 and 1944, although the extent of their role and which of their actions should be credited is debated. The group's leaders believed that the failure of the Europa Plan was due to the indifference of mainstream Jewish organizations. Although this argument has influenced public opinion and Orthodox Jewish historiography, most historians maintain that the Nazis would not have allowed the rescue of a significant number of Jews. It has also been argued that the Working Group's negotiations were collaborationist and that it failed to warn Jews about the dangers awaiting them, but most historians reject this view. Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer considers the Working Group's members flawed heroes who deserve public recognition for their efforts to save Jews.

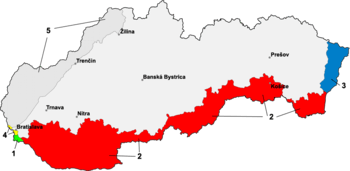

Background

On 14 March 1939, the Slovak State proclaimed its independence from Czechoslovakia under German protection; Jozef Tiso (a Catholic priest) was appointed president.[7] According to the Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, the persecution of Jews was "central to the domestic policy of the Slovak state".[8] Slovak Jews were blamed for the 1938 First Vienna Award[9][10]—Hungary's annexation of 40 percent of Slovakia's arable land and 270,000 people who had declared Czechoslovak ethnicity.[11] In the state-sponsored media, propagandists claimed that Jews were disloyal and a "radical solution of the Jewish issue" was necessary for the progress of the Slovak nation.[12] In a process overseen by the Central Economic Office (led by Slovak official Augustín Morávek), 12,300 Jewish-owned businesses were confiscated or liquidated; this deprived most Slovak Jews of their livelihood. Although Jews were initially defined based on religion,[10][13] the September 1941 "Jewish Code" (based on the Nuremberg Laws) defined them by ancestry. Among the Code's 270 anti-Jewish regulations were the requirement to wear yellow armbands, a ban on intermarriage, and the conscription of able-bodied Jews for forced labor.[14][15][13] According to the 1940 census, about 89,000 Jews (slightly more than three percent of the population) lived in the Slovak State.[13]

Jewish Center

Dieter Wisliceny, representing Reich Main Security Office Jewish-section director Adolf Eichmann, arrived in Bratislava as the Judenberater for Slovakia in September 1940.[16][17] His aim was to impoverish the Jewish community so it became a burden on gentile Slovaks, who would then agree to deport them.[17] Wisliceny ordered the dissolution of all Jewish community organizations and forced the Jews to form a Judenrat called the Jewish Center (Slovak: Ústredňa Židov, or ÚŽ).[16] The first such organization outside the Reich and German-occupied Poland, ÚŽ was the only secular Jewish organization permitted; all Jews were required to be members.[18][19] Leaders of the Jewish community were divided on how to react to this development. Some refused to associate with the ÚŽ in the belief that it would be used to implement anti-Jewish measures, but more saw participating in the ÚŽ as a way to help their fellow Jews by delaying the implementation of such measures. As a result, the ÚŽ was initially dominated by Jews who refused to collaborate and focused on charitable projects (such as soup kitchens) to help those impoverished by the anti-Jewish measures.[20]

The first leader of the ÚŽ was Heinrich Schwartz, longtime secretary of the Orthodox Jewish community, who had been chosen for his fluency in Slovak.[21][lower-alpha 3] Schwartz thwarted anti-Jewish orders to the best of his ability by delaying their implementation. He sabotaged a census of Jews in eastern Slovakia which aimed to move them to the west of the country, and Wisliceny had him arrested in April 1941.[21][24] Schwartz' replacement was Arpad Sebestyen, who fully cooperated with Wisliceny.[25][26] However, Sebestyen was aware of the activities of the Working Group and made no effort to stop them or report them to the authorities.[27] Wisliceny formed the Department for Special Affairs within the ÚŽ to ensure the prompt implementation of Nazi decrees, appointing Karol Hochberg (an ambitious, unprincipled Viennese Jew) as its director.[21][25][28] Hochberg carried out the removal of Jews from Bratislava, tarnishing the ÚŽ's reputation in the Jewish community.[3][29] Due to Sebestyen's ineffectiveness, Hochberg's department came to dominate ÚŽ operations.[30]

Formation

Dissatisfied with this state of affairs and fearful of voicing their concerns aloud due to Hochberg's influence, during the summer of 1941 many ÚŽ members began meeting in the office of ÚŽ director of emigration Gisi Fleischmann. Fleischmann's office was across the street from the main Jewish Center, which helped keep the group's activity secret. It was eventually formalized into an underground organization which became known as the Working Group.[21][25][3][lower-alpha 1] The group included Jews from across the ideological spectrum, working in concert to oppose the Holocaust.[31][2]

Fleischmann was the first cousin of Shmuel Dovid Ungar (a leading Oberlander Orthodox rabbi), but had abandoned religious Judaism for Zionism at a young age.[32] Fleischmann had been active in Jewish public-service organizations before the war, founding the Slovak chapter of the Women's International Zionist Organization and becoming leader of Slovakia's Joint Distribution Committee (JDC). Her prewar volunteer work had impressed international Jewish organizations such as the JDC, the World Jewish Congress (WJC) and the Jewish Agency for Palestine, whose aid the Working Group needed to fund its operations. Her colleagues admired her dedication to public service and ability to motivate individuals with opposing ideological views to work together towards a common goal.[33][34]

The other members of the group were Oskar Neumann, Tibor Kováč, Armin Frieder, Wilhelm Fürst, Andrej Steiner, and Shlomo Gross.[31][35] Neumann led the World Zionist Organization in Slovakia,[36] Kováč was an assimilationist, Frieder was the leading Neolog rabbi in Slovakia, and Steiner was a "non-ideological" engineer.[1] Gross represented the Orthodox community.[35] From the beginning, the Working Group had the support of moderates in the Slovak government (including minister of education Jozef Sivák; Imrich Karvaš, the governor of the national bank, and attorney Ivan Pietor), who kept the Working Group informed about the government's next moves.[37][38] Jakob Edelstein, a leader of Prague's Jewish community leader and later Theresienstadt concentration camp's Jewish elder, visited Bratislava in the autumn of 1941 and advised against cooperation with the German authorities.[1]

Michael Dov Weissmandl, a rabbi at Ungar's yeshiva, became involved in the Working Group in March 1942. He attended a meeting in Gross' stead when the latter was forced into hiding, and eventually replaced him as the group's Orthodox representative.[39] Due to its lack of representation of Orthodox Jews, Weissmandl initially objected to the Working Group;[2][39] however, he eventually concluded that the group's members were "devoted, upright, and extremely reliable people" who were working to save the Slovak Jewish community from deportation and death.[39] Due to the general respect for his wisdom and integrity, Weissmandl became a key figure in the Working Group.[40] He was the only member of the group who was not a member or employee of the ÚŽ,[41] although he did have close connections with the Orthodox faction of the ÚŽ.[25]

Many historians state that Fleischmann was the leader of the Working Group.[lower-alpha 4] Other sources are less specific about her role, stating that the group was led by Fleischmann and Weissmandl,[43][44] or not describing an explicit hierarchy.[45] Scholars have debated why Weissmandl, with his strongly anti-Zionist views and conservative Orthodox philosophy, readily accepted the leadership of a woman and Zionist.[46][47][40] According to Weissmandl, Fleischmann's leadership and interpersonal skills led him to accept her; the fact that she was a woman prevented leadership disputes.[42][48][49] Bauer notes that Weissmandl was Ungar's son-in-law, and posits that Fleischmann's cousin approved her leadership of the group.[48]

Initial efforts

During the summer of 1941, the Germans demanded 20,000 men from Slovakia for forced labor. Slovakia did not want to send gentile Slovaks, but neither did it want to care for the families of deported Jews.[50] The Jews were also a political bargaining chip between opposing factions of the Slovak People's Party who both sought to curry favor with the Germans. Tiso's political rival, Prime Minister Vojtech Tuka, organized the deportations and reported the preparations to papal chargé d'affaires Giuseppe Burzio in an attempt to discredit Tiso's Catholic credentials. Nevertheless, Tiso went through with the deportations to retain German support.[51][52] A compromise was reached in which the families of Jewish workers would accompany them, and the Slovaks would pay 500 Reichsmarks per Jew deported.[53] Slovakia was the only country to pay for the deportation of its Jewish population,[54] and the only country besides Nazi Germany to organize the deportation of its own Jewish citizens.[55]

The Working Group learned in late February 1942, probably from the Slovak government official Jozef Sivák, that the Slovak government was planning to deport all Jews to Poland. Although it was a shock, Israeli historian Gila Fatran notes that deportation was the logical outcome of the Slovak State's antisemitic policies. The Working Group believed that persuading Tiso was key to stopping the deportations, a view shared by its sympathizers in the government.[3][56] The group met on 25 February, agreeing to take a three-pronged approach to stopping the transports:[35]

- Issuing two petitions to Tiso, one from Jewish community organizations and the other from the rabbis

- Convincing business leaders that deporting Jews would compromise the economy

- Persuading the Catholic Church to intervene on humanitarian grounds

The petition from community leaders, delivered on 5 March, used pragmatic arguments for allowing the Jews to remain in Slovakia. The petition from the rabbis, delivered to Tiso on 8 March by Armin Frieder, condemned the deportations in emotive language.[35][57] Although no one in Slovakia knew about the planned Final Solution—the murder of all Jews in Nazi Germany's reach—the petitions stressed that deportation entailed "physical extermination" based on the poor conditions for Jews in Poland and news of the massacre of Soviet Jews after the invasion of the Soviet Union.[35][56] Tiso did not interfere;[58][59] despite the ban on Jews issuing official documents, the petitions were widely duplicated and circulated among Slovak government officials, legislators, bishops, and other Catholic religious leaders. However, the Slovak government supported the deportation of Jews and the protests were ineffective.[35][56]

The Working Group also begged Catholic officials to intercede on humanitarian grounds, hoping that their Christian faith would prevent them from supporting deportation.[60] The Vatican responded with a letter protesting against the deportations which was delivered to the Slovak ambassador on 14 March.[61][62] Burzio condemned the deportations in strong language in April and, according to Sicherheitsdienst (SD) reports, threatened Tiso with an interdict if he went through with them.[58][63] In response, the Slovak bishops issued a statement on 26 April accusing the Jews of deicide and of harming the Slovak economy.[63][64][65]

After failing to stop the deportations, the Working Group became increasingly demoralized;[66] however, they attempted to save as many Jews as possible. A Claims Department, led by Kováč, was set up in the ÚŽ to help Jews obtain exemptions from transport[67] and ensure that the Slovak government would honor exemptions already issued.[39] Between 26 March and 20 October 1942, about 57,000 Jews (two-thirds of the Jews in Slovakia at the time) were deported.[63][68] Eighteen trains went to Auschwitz and another thirty-nine went to ghettos and concentration and extermination camps in the Lublin district of the General Government occupation zone.[69][70] Only a few hundred survived the war.[58][68]

Aid to deportees

Intelligence gathering

The Working Group tracked the destinations of the deportation trains, learning that young women were deported to Auschwitz and young men to various sites in the Lublin district (where they were forced to work on construction projects). Deportees brought chalk which they used to write the destination on the railway carriages which returned, empty, to Slovakia.[71][70] A few managed to send postcards along the route, with disguised references to their location and the terrible conditions on Holocaust trains.[70] Although the Slovak railway company turned the trains over to the Deutsche Reichsbahn at the border, one Slovak railway worker accompanied each train to ensure that the equipment would be returned intact.[72] The Working Group interviewed these railway workers, and obtained destinations from them. Little was known about the sites to which the Jews were being taken, however, and no information about extermination facilities was available.[71][70]

Polish-speaking couriers, mostly from villages along the Polish-Slovak border, were employed to illegally cross the border and establish contact with the deportees. According to Weissmandl, contact was established with some by late April or early May.[73][74] Through the couriers, the Working Group obtain reasonably accurate information on the horrible conditions in which deportees were held; this was in addition to vague allusions in censored messages the Germans allowed them to send.[74] These letters were forwarded to the ÚŽ by their recipients in Slovakia. Additional reports reached the Bratislava activists from Jews in the countryside who had special permits allowing them to travel.[75] The Working Group also used its couriers to track deportees from the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Austria and Belgium, and to keep abreast of the situation of Jews at Theresienstadt and in the Czech lands.[76]

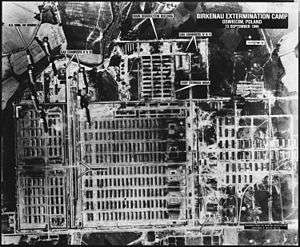

By the end of the summer, the only locations with which the Working Group had not established contact were Birkenau and Majdanek. Accurate information on these camps was not available because anyone caught within eight kilometers would be summarily executed, so as late as September 1943 (despite reports of an extermination camp at Auschwitz) Birkenau and Majdanek were still described as heavily guarded forced-labor camps.[77] In August many Slovak Jewish deportees were transported a second time, to extermination camps, with many Jews murdered in the roundups. News of this reached the Working Group by the end of the month; in October the couriers reported that Slovak Jewish deportees had been sent to "the other side of the Bug" (Bełżec extermination camp), where there were reportedly facilities for mass murder using poison gas. They also informed the Working Group of the Grossaktion Warsaw in which most of the Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto had been deported during the summer of 1942. Although the Working Group passed these reports on to its Swiss contacts in December, it downplayed them in its letter and sent the couriers back to confirm the reports (indicating that the group doubted the accuracy of the information). In this respect, their knowledge of the Final Solution was less complete than that in the Western world at the time.[78]

During the winter of 1942–43, the mass murder of Jews in Lublin and harsh weather hampered the work of the couriers. In February 1943, however, the Working Group received information that other Slovak Jews deported from the Lublin area had also been sent to Bełżec (corroborating reports of extermination facilities there). From then on, the group knew that those deported a second time had been murdered.[79] Later that spring, the couriers told the Working Group that about 10,000 Jews were still alive in the Bochnia and Stanisławów Ghettos. The Stanisławów Ghetto was liquidated before help could arrive, but the couriers urged the Jews in Bochnia to escape and provided information on routes.[80] In 1943, the Working Group still believed—erroneously—that most able-bodied Jews were allowed to live.[77]

Evasion and escape

Slovak officials promised that deportees would not be mistreated and would be allowed to return home after a fixed period.[81] Initially, even most youth-movement activists believed that it was better to report rather than risk reprisals against their families.[82] This was accompanied by a campaign of intimidation, violence, and terror by the Hlinka Guard, which carried out many of the roundups.[83] The first deportee reports trickled in during May and June 1942, citing starvation, arbitrary killings, the forcible separation of families, and poor living conditions.[84] Neumann sent members of banned Zionist youth movements by train with these reports to warn Jews to hide or flee, a task made more difficult by strict censorship and travel restrictions.[85][41][44] By June, accumulating evidence of Nazi perfidy caused many Jews not to appear for deportation or wait at home to be rounded up. Many tried to obtain false papers, fraudulent conversion certificates, or other exemptions.[86][87] Several thousand[lower-alpha 5] Jews fled to Hungary, aided by Rabbi Shmuel Dovid Ungar and the youth movements, in the spring of 1942.[31] Many others were arrested at the border and immediately deported.[85] Because Jews were not reporting for their transports, the Hlinka Guard forcibly rounded up Jews and deported some prisoners in the labor camps in Slovakia, who had been promised that they would not be deported.[61][68]

According to historian Yehoshua Büchler, the Working Group's most important sources of information on the fate of deported Jews were escapee reports.[91] Majdanek, where young Slovak Jewish men were sent, had had an active escape committee from April 1942. Dozens of escape attempts were made; the most significant was that of Dionýz Lénard, who returned to Slovakia in July and reported on the high Jewish death rate from hunger (but not on the Final Solution).[92][93] Other Slovak Jews escaped from ghettos in the Lublin area, including the Opole Lubelskie, Łuków, and Lubartów Ghettos.[91][94] An escapee from the Krychów forced-labor camp submitted a report to the Working Group which was forwarded to Istanbul.[94] In the early summer of 1943, three fugitives brought more information on extermination camps. David Milgrom, a Polish Jew from Łódź, had escaped from Treblinka in late 1942 and lived as a gentile in Poland before being smuggled into Slovakia by Working Group couriers. Milgrom, an unknown Slovak Jewish escapee from Sobibor, and another person who had spoken with an escapee from Bełżec reported to the Working Group, and their testimony was relayed to Jewish groups in Switzerland.[95] These reports finally convinced the Working Group of the German plan for total extermination of all Jews.[77]

In 1943, the Working Group helped Polish and Slovak Jews escape from Poland.[96][80] A Slovak Jewish taxi driver named Schwartz, based in Prešov (near the Polish border), helped smuggle Polish Jewish refugees over the Carpathian Mountains to Hungary but charged high fees and used harsh measures on those unable to pay. The Working Group enlisted him and similar individuals to set up smuggling operations in Prešov and other border towns, including Kežmarok, Žilina, and Liptovský Svätý Mikuláš.[97] The Zionist youth movements set up a cottage industry forging false papers; priority was given to Polish Jews, who were more vulnerable to deportation.[97][44][98] According to the Aid and Rescue Committee, between 1,900 and 2,500 adults and 114 children reached Hungary by late November 1943.[97] The success of this operation was dependent on the lukewarm attitude of the Slovak government to persecuting the Jewish refugees, a fact which Fatran attributes to lobbying by the Working Group.[99]

Efforts to inform the world

Information on the progress of the Holocaust was transmitted to the Working Group's contacts, including the Aid and Rescue Committee, Orthodox rabbi Pinchas Freudiger in Budapest, and Jewish groups in Switzerland.[100][86] The Working Group used diplomatic parcels, undercover messengers, and codes based on Hebrew and Yiddish words to bypass German censorship; Wisliceny's codename was "Willy".[101][102] Most of the correspondence was intercepted by the Abwehr in Vienna; the letters were returned to Bratislava, where German police attaché Franz Golz gave them to Wisliceny (who had jurisdiction over Jewish issues).[102] Slovak historian Katarína Hradská has suggested that the Riegner Telegram, an August 1942 report on the Holocaust, was derived in part from information provided by the Working Group, particularly the report by Majdanek escapee Dionýz Lénard.[103]

In late July 1942, the Working Group received a report of a massacre of Jews in Poland; as with other reports of atrocities, it forwarded the information to the Slovak government. Church officials and cabinet members pressured the government, and Prime Minister Vojtech Tuka asked Wisliceny to authorize a delegation of Slovak priests to the General Government zone to disprove the report.[104][105] Wisliceny had to travel to Berlin to notify Eichmann of this request. Instead of priests, the Nazis sent Wisliceny and Friedrich Fiala (the Slovak editor of a fascist newspaper, who used the visit as fodder for antisemitic propaganda). This incident probably convinced the Germans to relax their pressure on the Slovak government regarding deportations;[106][45][107] a transport scheduled for 7 August was cancelled, and deportations did not resume until mid-September.[108]

In 1943, moderate government officials who opposed the deportations could use information on the fate of deported Jews to justify their opposition. The Slovak church also took a less favorable attitude towards renewed transports than it had the previous year, which historian Gila Fatran attributes to the Working Group's news of mass deaths. In response to renewed Slovak demands to see the sites where Slovak Jews were imprisoned, Eichmann suggested that they visit Theresienstadt (where Slovak Jews had not been sent). The Slovak representatives were not allowed to go to Lublin, because most Slovak Jewish deportees had already been murdered.[109][110] Although the Working Group received the report of Auschwitz escapee Jerzy Tabeau and forwarded it to Czechoslovak government-in-exile ambassador Jaromír Kopecký in Switzerland, when and how are unclear.[111]

Relief

The Polish-speaking couriers delivered money and valuables, and smuggled letters back to Slovakia. A few letters saying that the recipient's life had been extended by the aid received persuaded the Working Group to intensify its efforts in the face of increasing evidence that the deportees were being systematically murdered.[73][112][113] Aiding deportees was a priority of the Working Group and the deportees' families and communities.[114] Through the couriers and vague allusions in censored messages from deportees, the Working Group obtained reasonably accurate information on the horrible conditions in which deportees were held. Coordinating its efforts with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the Jewish Self-Help Organization in Kraków and relatives of deportees, the Working Group attempted to track down exact addresses for aid parcels. In a July 1942 letter to WJC representative Abraham Silberschein, Fleischmann reported that the Working Group had obtained only 2,200 addresses for the tens of thousands of deported Jews.[115][116]

Zionist youth-movement activists used the information to track down deported activists and send aid to them.[91] Attempts to send money via the Slovak National Bank failed when the recipients were not found, forcing the Working Group to rely even more on the couriers (who were also charged with finding and aiding escapees). In May 1943, pressure from the Working Group caused the Slovak government to allow them to send packages of used clothing to known addresses in the Protectorate, the Reich, and the General Government zone. Fleischmann, who was in charge of the ÚŽ welfare department at the time, oversaw this operation. The only confirmed deliveries were to Theresienstadt.[117] Through couriers, the Working Group maintained contact with a group of able-bodied Jews used for forced labor on Luftwaffe airfields near Dęblin until 23 July 1944 (when the camp was liquidated). This was the last substantial surviving group of Slovak Jews in the Lublin district.[118]

Fleischmann sent a letter on 27 August 1942 to Nathan Schwalb, HeHalutz representative in Switzerland, expressing doubt that the deported Jews would ever be seen alive again. Writing that the cash-strapped local community had already spent 300,000 Slovak koruna (Ks) on relief efforts, she asked Schwalb for a monthly budget for relief efforts. Frieder and Weissmandl, deeply involved in the illegal relief efforts, were arrested on 22 September but continued their work when they were released. The Working Group received 20,000 Swiss francs from the JDC via a courier in November, their first support from an international Jewish organization. Although the JDC later deposited this sum monthly in an account at the Union Bank of Switzerland (earmarked for Working Group relief and bribery operations), it was usually insufficient for the group's needs; Fleischmann frequently had to remind the Jewish organizations in Switzerland to honor their promises to her. The money was transferred to Bratislava via Hungary, delaying its availability.[119]

Negotiation and bribery

Bribery of Slovak officials

.jpg)

Negotiations to save Slovak Jews with bribery began at Weissmandl's initiative in mid-June 1942.[120][121] The Working Group immediately approached the Slovak officials responsible for Jewish affairs,[121] who had demonstrated their corruptibility when they accepted bribes for preferential treatment during the liquidation of Jewish businesses.[18] Initially, officials were bribed to add more names to the list of Jews deemed essential to the economy (exempting them from deportation).[122]

The most influential official to be bribed was Anton Vašek, head of the Ministry of the Interior department responsible for implementing the deportations.[26][39] Although he began accepting bribes in late June 1942, he continued to organize transports[66][123] and said publicly that the "Jewish question must be solved 100 percent".[124] Due to his "high-handedness" in exercising the power over life and death, Vašek became known as "King of the Jews";[39][123] he was known to pull Jews out of cattle wagons after receiving a bribe, only to send them on the next transport.[123] Vašek's desire for money to fund his gambling and womanizing made him susceptible to bribery.[39][123] Tibor Kováč, a member of the Working Group and Vašek's former classmate, visited his office almost daily to deliver the bribes and provide him with excuses to explain the delay to his superiors.[125] The Working Group promised Vašek 100,000 Ks (about $1,600) for each month without deportations.[125][38] Due to Vašek's intervention, a 26 June transport of Jews was cancelled; Vašek presented Interior Minister Alexander Mach with a falsified report that all non-exempt Jews had already been deported. Mach was skeptical about the report, however, and the deportations resumed in July.[121]

Other officials accepted bribes from the Working Group. Augustín Morávek was dismissed in July 1942, coinciding with the slowdown in deportations.[38] Isidor Koso, head of the prime minister's office and the person who had initially proposed the deportation of Jews, received a monthly payment from the Working Group in 1942 and 1943.[126][127] Afraid of being caught, Koso refused to make personal contact with Fleischmann. However, his wife, Žofia Kosova, provided the Working Group with updates on the government's plans for the remaining Slovak Jews in exchange for bribes.[127][128] Finance minister Gisi Medricky, labor-camp director Alois Pecuch,[26][129] deportation commissioners Ján Bučenek and Karol Zábrecky, gendarme officers who ran the labor camps, and government officials with no power over deportations but useful information for the Working Group were all bribed. Although the group attempted to bribe Tiso, there is no evidence that they were successful.[129] After the war, Slovak officials denied accepting bribes.[38]

Slovakia Plan

The Working Group's negotiations with Dieter Wisliceny began during the summer of 1941, when Shlomo Gross attempted to arrange emigration. These contacts informed the Slovak Jewish leaders that Wisliceny was susceptible to bribery and the SS hierarchy was eager to get in touch with representatives of "International Jewry", whose influence on the policies of the Western Allies was greatly exaggerated in the Nazi imagination.[130] Gila Fatran suggests that Wisliceny was desperate for money;[104] Israeli historian Livia Rothkirchen emphasizes his craving for recognition, since he had been passed over for promotion in favor of Eichmann.[131] However, unlike the Slovak representatives, contact with Wisliceny carried a high risk and had to be done secretly. Hochberg, who made regular visits to Wisliceny's office, was employed as an intermediary as a last resort; the Working Group considered Hochberg a collaborator, feared that associating with him would harm their reputations, and believed him to be unreliable. Nevertheless, Fleischmann and Weissmandl agreed that it was worth making a deal with the devil to rescue Jews. At this point, the structure of the Working Group was formalized to improve its efficiency and the secrecy of its operations; Fleischmann was unanimously chosen to lead the bribery department. Due to the disagreement about involving Hochberg, negotiations with Wisliceny did not begin until mid-July[130][132] or early August.[133]

.jpg)

Exploiting Wisliceny's desire to contact international Jewish organizations, Weissmandl forged letters from "Ferdinand Roth", a fictitious Swiss official. In mid-July, Hochberg brought the letters to Wisliceny. He told the Working Group that Wisliceny had the power to stop the deportations from Slovakia and demanded $40,000 to $50,000, paid in two installments, in exchange for delaying the deportations until the following spring.[120][121][134] Hochberg also relayed Wisliceny's suggestion to expand the labor camps at Sereď, Nováky, and Vyhne to "productivize" the remaining Jews and create a financial incentive to keep them in Slovakia.[135][lower-alpha 6] The Working Group, not having expected an affirmative response, began to hope that it could save the remaining Slovak Jews.[121][132] Slovak Jewish businessman Shlomo Stern donated the first $25,000 in US dollars,[lower-alpha 7] which was probably delivered to Wisliceny on 17 August. The balance of the payoff was due in late September.[139][121][140] What happened to the money is unclear, but it was probably embezzled by Hochberg[lower-alpha 8] or Wisliceny.[104][133] Deportations were halted from 1 August to 18 September, and the Working Group assumed that its ransom operations had borne fruit.[133][45][142][lower-alpha 9]

The meeting between Hochberg and Wisliceny probably occurred after Tuka's request to send a Slovak delegation to the General Government zone, which convinced the Germans to reduce their pressure for deportations. Wisliceny collected the Jews' money and took credit for the reduction in transports. He simultaneously tried to persuade the Slovak government to approve the resumption of deportations, sending a memo to Tuka and Mach claiming that only indigent Jews were deported. Wisliceny recommended raids on Jews in hiding, cancellation of most economic exceptions, and the deportation of converts (who would be settled separately from Jews). If this was done, Wisliceny claimed, twenty-three trains could be filled and Slovakia would be the first country in southeastern Europe to become Judenrein ("cleansed of Jews"). Wisliceny pointed out that Tiso, a member of a rival faction of the Slovak People's Party, had recently claimed in a speech that Slovakia's development could only progress after the remaining Jews were deported.[106][144][145] The Working Group was unaware of Wisliceny's advocacy for continued deportations. He pretended to be on the Jews' side and was reasonable and polite, but claimed to need large sums of money to bribe his superiors.[134][146]

The JDC in Switzerland was hamstrung by restrictions on sending currency to Switzerland, and had to employ questionable smugglers to bring funds into Nazi-occupied Europe. Although Mayer was sometimes able to borrow money in Swiss francs against a postwar payment, he was unable to send the dollars demanded by Wisliceny.[147] In August and September, Weissmandl pressed his Orthodox Jewish contacts to provide the remaining $20,000. When another transport left Slovakia on 18 September, Weissmandl cabled Jewish leaders in Budapest and blamed them for the deportation. A second transport departed on 21 September, Yom Kippur. The money (donated by Hungarian Jewish philanthropist Gyula Link) probably arrived the next day,[148][149] although other sources report that the Working Group did not make the second payment until November.[150] Wisliceny forwarded $20,000 to the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office in October with the knowledge of the German ambassador to Slovakia, Hanns Ludin, via police attaché Franz Golz.[151] On 20 October, the last transport for nearly two years departed with 1,000 physically or mentally disabled Jews.[104] The Working Group assumed that the bribe had been successful.[44][152]

Europa Plan

The Working Group's contacts at the Slovak railway informed them that deportations would not resume until spring 1943. Although the group contacted Wisliceny about the evacuation of Slovak Jewish children from Lublin to Switzerland or Palestine, nothing came of it.[153][154] Weissmandl, who credited the bribing of Wisliceny with stopping the trains, believed that the Slovak Jewish leaders had an obligation to help their fellow Jews in other Nazi-occupied countries. He proposed attempting to bribe Wisliceny's superiors into halting all transports to the General Government zone, a proposal which became known as the Europa Plan. Many of the Working Group's members were skeptical of the plan, arguing that Wisliceny had been acting on his own. A larger-scale operation would be doomed to fail, and might trigger the deportation of the remaining Slovak Jews.[151] Only Fleischmann, Weissmandl, and Neumann thought the Europa Plan worth pursuing.[155][156]

In November 1942, Wisliceny told the Working Group that Reich Main Security Office head Heinrich Himmler had agreed to halt deportations to the General Government zone in exchange for $3 million.[45] Hochberg was arrested later that month for bribery and corruption.[lower-alpha 10] As a result, the Working Group took control of the ÚŽ's day-to-day operations[157] and Steiner (and later Fleischmann) met with Wisliceny directly.[158][159] The following month, Himmler obtained permission from Hitler to begin negotiations to ransom Jews for hard currency;[160] however, the Working Group could not raise the money. The JDC, skeptical of the proposal[161] and reluctant to give money to Nazis,[162] did not send any additional money to Switzerland. Mayer funneled money to the Working Group[161] despite his reluctance to violate the Trading with the Enemy Act.[162] The Hungarian Jewish community was unable or unwilling to help.[161] The Working Group contacted Abraham Silberschein of the World Jewish Congress and Nathan Schwalb of Hehalutz.[45] Schwalb became a committed supporter of the plan and contacted Palestine directly, repeating the Working Group's impression that Wisliceny had kept his promises.[163]

Due to miscommunication, the scale of the Europa Plan was not understood by leaders in Palestine until a March 1943 visit by Jewish Agency treasurer Eliezer Kaplan.[164] Kaplan believed that the plan was impossible, but he relayed more optimistic opinions from some of his colleagues in Istanbul.[165] The Yishuv expressed willingness to help fund the plan,[166] although Kaplan, David Ben-Gurion, Apolinary Hartglas, and other leaders of the Jewish Agency and the Yishuv suspected that Wisliceny's offer was extortion.[167][168] In the meantime, Wisliceny had left Slovakia to supervise the deportation and murder of Thessaloniki Jews.[169]

The Working Group's attention was diverted by the threat of resumed transports from Slovakia, which were due to begin in April 1943.[169] As the deadline approached, Fleischmann and Weissmandl became even more militant in promoting the plan to Jewish leaders. They insisted that it was feasible, that the Nazis could be bribed, and the laws governing currency transfer could be bypassed. Although they had received only $36,000 by that month,[165] deportations from Slovakia did not resume.[169][170] Fleischmann met with Wisliceny, who told her that the deportations would be halted if the Nazis received a $200,000 down payment by June.[170] The Yishuv managed to transfer about half of that sum to the Working Group, probably by laundering contributions from overseas Jewish organizations and smuggling diamonds into Turkey.[171] The JDC, the WJC, and other organizations blocked the distribution of funds[172] because their leaders believed that the Nazi promises were empty.[173] In addition, the Swiss government obstructed currency transfers on the required scale. Mayer helped to the best of his ability, but could only smuggle $42,000 to the Working Group by June and an additional $53,000 in August and September.[172] However, some of this money was needed for improving the welfare of Jews living in labor camps in Slovakia,[lower-alpha 6] aiding deportees in Poland, or smuggling refugees to Hungary.[174] One of the Working Group's requests to Wisliceny as part of the plan was improved communication with deportees; according to Fatran, Wisliceny enabled the delivery of thousands of letters from Jews imprisoned at Auschwitz, Majdanek, and Theresienstadt in late summer 1943.[175]

Breakdown of negotiations

On 2 September 1943, Wisliceny met with Working Group leaders and announced that the Europa Plan had been cancelled[176] because the delay in payment caused the Nazis to doubt "Ferdinand Roth"'s reliability.[177] After the war, he claimed that Himmler had ordered him to break off contact with the Working Group, an interpretation supported by Bauer and Rothkirchen.[178][179] The Nazis' refusal to go through with their proposal shocked the Working Group members. During this meeting, Wisliceny attempted to reinforce the group's trust in him by leaking information that the Nazis were in the process of transferring 5,000 Polish Jewish children to Theresienstadt; from there, they would be sent to Switzerland if a British ransom was paid. He also told them that Bergen-Belsen was used to house "privileged" Jews before a potential exchange.[180] Although a transport of 1,200 children from the Białystok Ghetto was sent to Theresienstadt in August 1943,[181][141] the children were sent to Auschwitz on 5 October and gassed on arrival.[182]

Wisliceny left the prospect of reopening negotiations open.[177] The Working Group blamed itself for the plan's failure, and gave Wisliceny $10,000 on 12 September in the hope of reviving negotiations.[183] The fact that the murder of Jews continued apace[lower-alpha 11] made it obvious to international Jewish leaders that the Nazis were negotiating in bad faith.[184][44] By mid-October, it was clear to international Jewish leaders that the Nazis had abandoned the plan.[185][183] When Wisliceny appeared in Bratislava again in late 1943, however, the Working Group still hoped to salvage negotiations. When Fleischmann was caught bribing a Slovak official's wife in October 1943, an incident known as the "Koso affair", communications with Jewish organizations in Switzerland were severed, so the Working Group could not guarantee that it would be able to raise the money. In early January 1944, Fleischmann was arrested again and Wisliceny left for Berlin.[71] These negotiations, as well as the prior negotiations over the Europa Plan, may have paved the way for the later blood-for-goods proposal to ransom Hungarian Jews after the German invasion of Hungary.[71][186]

The Holocaust in Hungary

Takeover of the Jewish Center

The Working Group took advantage of a reorganization in the Slovak government to remove Arpad Sebestyen, the ineffectual leader of the ÚŽ, in December 1943. The Jewish community was allowed to choose his successor; the Working Group voted unanimously for Oskar Neumann.[27][187] With full control over the ÚŽ, the Working Group distributed information about rescue operations in official circulars. Planning for how to keep the remaining Jews alive during the coming Axis defeat was the focus of the group's meetings during the next few months.[188] It continued sending aid to surviving Jews in Poland and Theresienstadt, with the resumption of deportations from Slovakia a constant threat.[188][157][189] Due to the fallout of the Koso affair, Fleischmann was forced to go in and out of hiding to avoid arrest.[188] She was arrested again on 9 January 1944, and imprisoned for four months at the Nováky camp and the Ilava prison. The Working Group sought her release and escape to Palestine, but Fleischmann refused to leave Bratislava.[190][191] Slovak authorities began to re-register Jews, prompting some to flee to Hungary.[188]

After the March 1944 German invasion of Hungary, the flow reversed and Slovak and Hungarian Jews fled back across the border to Slovakia.[188] At this time, the approximately 800,000 Jews (as defined by race) in Hungary was the largest surviving population in Europe. The Jews in Hungary had been subjected to strict antisemitic legislation and tens of thousands had been murdered, both young men conscripted into labor battalions and foreign Jews deported to Kamianets-Podilskyi, but they had not yet been deported en masse or systematically exterminated.[192] After the German invasion, the Working Group learned from sympathetic Slovak railway officials about the preparation of 120 trains for Jews deported from Hungary and relayed the information to Budapest, where it was received by the end of April.[193]

Vrba–Wetzler report

The Working Group played a central role in the distribution of the Vrba–Wetzler report in the spring of 1944. Two Auschwitz inmates, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, escaped and reached Slovakia on 21 April. After the Working Group heard of Vrba and Wetzler's escape, Neumann was dispatched to interview them; the report was completed on 27 April.[194][195] The 40-page report corroborated previous Auschwitz reports which had been forwarded to Britain by the Polish government-in-exile.[196][197] A copy of the report was sent to the head of the Judenrat of Ungvar in Carpathian Ruthenia, who unsuccessfully tried to suppress its contents. Although the information was transmitted to two other Carpathian Ruthenian transit ghettos, the Jews did not act on the report.[198] Oskar Krasniansky, who helped transcribe the report, claimed that Hungarian Zionist leader Rudolf Kastner visited Bratislava on 26 or 28 April and read a copy of the report (which was not completed until the 27th). However, Hansi Brand denied that Kastner had been to Slovakia before August.[199]

The general information in the report was smuggled into Hungary by non-Jewish couriers, reaching Budapest by early May. By the same route, the report itself reached an antifascist Lutheran organization in Budapest in late May. There were probably other, unsuccessful attempts by the Working Group to send the report.[200] Using its ties to the Slovak resistance, the Working Group sent information in the report on 22 May to Jaromír Kopecký (who received a full copy by 10 June).[201][202] In an attached letter, the group informed Kopecký about preparations for deportations from Hungary.[202] Kopecký transmitted this information to the United States State Department[76] and the ICRC in a 23 June message, reporting that 12,000 Hungarian Jews were being sent daily to their deaths.[203] The Czechoslovak government-in-exile asked the BBC European Service to publicize the information in the hope of preventing the murder of Czech Jews imprisoned at the Theresienstadt family camp at Auschwitz.[204][205] On 16 June, the BBC broadcast warnings to the German leadership that it would be tried for its crimes.[206][207] It is unclear whether the warnings influenced the fate of the Czech prisoners[111] although Polish historian Danuta Czech believes that they delayed the liquidation of the camp until July.[208]

Two more escapees, Arnošt Rosin and Czesław Mordowicz, reached Slovakia on 6 June and provided more information on the murder of the Hungarian Jews.[209][195] At the request of Burzio, Krasniansky arranged a meeting between Vrba, Mordowicz, and papal representative Monsignor Mario Martilotti, who interviewed the escapees for six hours on 20 June. According to British historian Michael Fleming, this meeting may have influenced the 25 June telegram of Pope Pius XII to Horthy, begging him to stop the deportations.[210][211]

Auschwitz bombing proposal

On 16 or 18 May, Weissmandl sent an emotional plea for help to Nathan Schwalb and detailed steps that the Allies could take to mitigate the disaster. Among his suggestions was to "blow up from the air the centers of annihilation" at Auschwitz II-Birkenau and the rail infrastructure in Carpathian Ruthenia and Slovakia used to transport Hungarian Jews to the camp.[212][201][213] Kopecký forwarded these suggestions, and on 4 July the Czechoslovak government-in-exile officially recommended bombing the crematoria and the rail infrastructure; their military significance was emphasized.[214] Although neither Auschwitz nor its rail lines were ever bombed, a cable mentioning the proposal was sent on 24 June by Roswell McClelland, the War Refugee Board representative in Switzerland.[215][216] The Hungarian government, which had claimed that the Allied aerial bombing of military targets in Budapest in April was directed by an international Jewish conspiracy,[217] intercepted the cable.[215][216] According to Bauer, the mention of bombing in the cable was interpreted by Hungarian leaders as confirming this erroneous belief.[218] By early July, the only remaining Hungarian Jews were in Budapest.[219] Hungary's Fascist regent, Miklós Horthy, believed that their presence protected the city from carpet-bombing[218] and the 2 July bombing of Budapest by the United States Army Air Forces was a reaction to the deportations.[216]

Information from the Vrba–Wetzler Report was smuggled from Hungary to diplomat George Mantello in Switzerland, who published it on 4 July.[201][111] Over the next eighteen days, at least 383 articles about Auschwitz which were based on information in the report were published in Swiss and international media.[111] Because of the publicity, Allied leaders (including US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill) threatened Horthy with a war-crimes trial if he did not stop the transports.[220] Pope Pius XII, Gustav V of Sweden, and the Red Cross also made appeals.[215] Horthy offered to allow 10,000 Jewish children to leave Hungary and unofficially halted the deportations on 7 July (with about 200,000 Jews still in Budapest),[221][215] justifying his change in policy to the Germans by claiming that a Judenrein Budapest would be carpet-bombed.[218][216] Mounting international pressure and the fact that Horthy could no longer claim ignorance of the deportees' fate (since he had a copy of the report) also probably played a significant role in the decision.[218] At the time, 12,000 Jews per day were being transported to Auschwitz.[222]

"Blood for goods" negotiations

After the invasion of Hungary, Wisliceny was sent there to organize the deportation of the Hungarian Jews. Weissmandl gave him a letter (written in Hebrew) saying that he was a reliable negotiator, and told him to show it to Pinchas Freudiger, Rudolf Kastner, and Baroness Edith Weiss (part of an influential Neolog family).[223][224] Freudiger focused on saving only his family and friends; Weiss was in hiding, but Kastner was a member of the Aid and Rescue Committee and able to take action.[225] The committee, under the impression that large bribes to Wisliceny had saved the remaining Jews in Slovakia, sought to establish connections with him immediately after his arrival in Budapest.[226] Wisliceny's superior, Adolf Eichmann, claimed that he would release one million Jews still living under Nazi occupation (primarily in Hungary) in exchange for 10,000 trucks.[227] During these negotiations, called "blood for goods", Joel Brand and other Jewish leaders adopted tactics used during the Slovakia and Europa Plan negotiations, including the use of forged letters.[228]

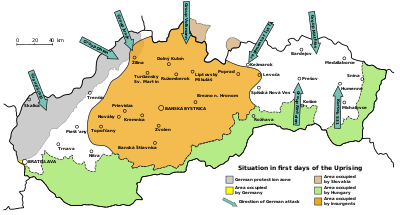

Kastner visited Bratislava in the summer of 1944 and informed the Working Group about events in Hungary, including the release of the Kastner train to Bergen-Belsen (the passengers were eventually allowed to leave for Switzerland). He asked the Working Group to help him raise money and obtain other commodities for ongoing negotiations with SS officer Kurt Becher. The group agreed to help, asking Kastner to request a moratorium on deportations from Slovakia. Fleischmann organized a committee of local Jewish businessmen to fulfill Kastner's requests. Kastner visited Bratislava again in late August with Becher's adjutant, Max Grueson. After the Working Group presented Grueson with a list of vital commodities which they could provide, Grueson promised to ask his superiors to allow Slovak Jews to flee. Before anything could be done, the Slovak National Uprising broke out after Germany invaded Slovakia.[229]

Dissolution

Overall situation

Because of Germany's imminent military defeat, much of the Slovak population and army leadership switched their allegiance to the Allies. Increasing partisan activity in the mountains presented a dilemma for Jews and, in particular, their leadership. To counter the perceived security threat of Jews in rural eastern Slovakia, the Slovak government proposed roundups; the Working Group convinced them to concentrate the Jews in western Slovakia. Although the Working Group did not support an uprising (because it feared the consequences for Slovakia's remaining Jews), Neumann gave an underground group in the Nováky labor camp funds for purchasing weapons. On 29 August, Germany invaded Slovakia in response to the increase in partisan sabotage. The Slovak National Uprising, which began that day, was crushed by the end of October.[229]

About 1,600 Jews fought with the partisans,[230] ten percent of the total insurgent force.[231] German and Slovak propaganda blamed them for the uprising,[232][233] providing the Germans with an excuse to implement the Final Solution.[234][235] Eichmann sent SS-Hauptsturmführer Alois Brunner to Bratislava to oversee the deportation and murder of about 25,000 surviving Jews in Slovakia.[236][237] Einsatzgruppe H, the Hlinka Guard Emergency Divisions, and the SS-Heimatschutz rounded up Jews and concentrated them in Sereď concentration camp for deportation to Auschwitz. Jews in eastern Slovakia were deported from other Slovak camps or massacred.[238][234]

Developments in Bratislava

Immediately after the German invasion, Neumann disbanded the ÚŽ and told its members to go into hiding or flee. Some Bratislava Jews infiltrated German intelligence operations and delivered daily reports to the Working Group, which the leaders used to decide whether or not to flee.[239] However, the Working Group did not issue a clear warning to Jews in western Slovakia to travel to partisan-controlled areas.[237] The group's leadership had shrunk significantly; Steiner was in central Slovakia upon the outbreak of the uprising and did not return to Bratislava, Weissmandl and his family were caught in a 5 September raid on Nitra and were held at Sereď,[240] and Frieder was arrested on 7 September in Bratislava.[241] Fleischmann had the opportunity to escape to the mountains, but refused to abandon her post.[242]

Due to the new Slovak government and changes in the German administration, the Working Group's contacts had been disrupted. With Grueson's help, the activists contacted Otto Koslowski (head of the SD in Slovakia), and arranged for the release of Weissmandl from Sereď. The Working Group offered Koslowski a list of goods worth seven million Swiss francs (including fifteen tractors) in exchange for the release of 7,000 Slovak Jews to Switzerland, claiming that these products (initially collected for the ransom of Hungarian Jews) could be shipped within a week. Their proposal was to send the Slovak Jews to Switzerland simultaneously with the shipment of the goods in the opposite direction.[242][243] Koslowski told the Working Group that a reply would arrive later, but at the next meeting he demanded that the Jewish leaders arrange for the orderly collection of Bratislava's Jews at Sereď and said that Brunner would arrive soon. On a visit to Bratislava on 18 September, Grueson warned the Working Group not to negotiate with Brunner.[242][237] It is unclear if the Working Group believed that the negotiations might be successful or used them as a delaying tactic, hoping to delay the murder of Slovak Jews until the war ended.[242]

Brunner arrived in Bratislava (probably on 22 or 23 September),[244] and the Working Group presented the proposal to trade commodities for Jewish lives. They also suggested improvements to Sereď to make the camp economically productive, as it had been before the uprising.[240] Brunner feigned interest in both of these proposals to distract the Working Group, arranging for a group of Jewish professionals to visit Sereď two days later.[240][245] On 24 September, Fleischmann wrote a letter to Switzerland requesting money for a new round of ransom negotiations.[246] During the visit to Sereď, the Jewish professionals from Bratislava were summarily dismissed by Brunner, but managed to learn of the murder of several inmates by guards. As a result, the Working Group recommended that the Jews in Bratislava go into hiding.[240]

28 September roundup

Fleischmann's office was raided on 26 September, giving the Germans a list of Jews. The Working Group, apparently not realizing the significance of this development, protested to Brunner (who agreed to punish the culprits).[247][237] On 28 September, Weissmandl and Kováč were summoned by Brunner on the pretext of being needed for a project at Sereď; they were imprisoned in Brunner's office, where they witnessed the use of the stolen list of Jews to prepare for a major roundup. Among the Jews at large in the city, competing rumors foretold a large operation or nothing would happen.[247] That night, Einsatzkommando 29 and local collaborators caught 1,800 Jews in Bratislava (including most of the Working Group's leadership).[237][248][249] Those arrested were held in the Jewish Center's headquarters until 6 am, when they were jammed onto freight cars and transported to Sereď (arriving at 2 am on 30 September). The first transport from Sereď since 1942 departed that day for Auschwitz, with 1,860 people.[250]

Deported with his family on 10 October, Weissmandl jumped off the train.[247][44][251] He was later rescued by Kastner and Becher and taken to Switzerland.[252][253] After the roundup, Fleischmann and Kováč were allowed to remain in Bratislava; Fleischmann refused to betray Jews in hiding, and was arrested on 15 October.[191][247] Two days later, she was deported on the last transport from Slovakia to be gassed at Auschwitz.[237][247] Labeled "return unwanted" by Brunner, Fleischmann was murdered upon her arrival.[246][191][254] Steiner, Frieder, Neumann, and Kováč survived, but Working Group treasurer William Fürst was deported and murdered.[255][256] In the second round of persecution, 13,500 Jews were deported (including 8,000 to Auschwitz) and several hundred murdered in Slovakia.[238][257]

Assessment

Overall

During the Holocaust, the Yishuv organizations in Istanbul noted the effectiveness of the Working Group's courier network and its inventiveness at reaching otherwise-inaccessible locations in occupied Poland, describing it as their "only window into the theatre of the catastrophe"; the Working Group's reports spurred other groups to take action to mitigate the Holocaust. Although the aid program could not save Jews from the Final Solution, it saved an unknown number from starvation temporarily.[86] The aid program was undertaken with little assistance from the Red Cross, which sought to maintain its neutrality by avoiding confrontation with Nazi Germany's genocidal policies.[258] Fatran writes that although the Europa Plan was "unrealistic" in hindsight, it was undertaken with the best of motives; the bulk of Slovak Jewry was not saved, but this was not due to the mistakes of the Working Group.[86][259]

According to Bauer, the Working Group was one of the only underground organizations in occupied Europe to unite the ideological spectrum (excluding communists) and to try to save Jews in other countries.[260] Livia Rothkirchen, who says that the "relentless" efforts of the Working Group achieved concrete results in multiple operations, emphasizes the uniqueness of a resistance group operating within a Nazi-directed Judenrat (which was necessary for the Working Group's successes).[261] In his introduction to a biography of Fleischmann, Simon Wiesenthal quotes Gideon Hausner (lead prosecutor at the Eichmann trial): "Gisi Fleischmann's name deserves to be immortalized in the annals of our people, and her memory should be bequeathed to further generations as a radiant example of heroism and of boundless devotion".[262] In a review of Slovakia in History, James Mace Ward described the group as "Bratislava’s legendary Jewish resistance circle" and regretted that it was not mentioned.[263]

According to Katarína Hradská, the Working Group had to negotiate with the Germans to achieve its goals; however, this led its members to self-delusion in their desperation to save other Jews from death.[264] Bauer argues that bribing Wisliceny was misguided since he did not stop the transports,[100] and that the Working Group should have issued clear warnings in September 1944, although such warnings "would have made no difference in any case".[260] Fatran writes that the conduct of the Working Group after the invasion can be explained by their previous apparent success with negotiation and their desperation to save the remaining Slovak Jews, recognizing that their actions were mistaken.[175] Bauer emphasizes that despite their faults and ultimate failure, the Working Group's members tried to rescue Jews and deserve to be recognized as heroes.[265]

Role in deportation hiatus

According to Israeli historians Tuvia Friling,[45] Shlomo Aronson,[266][267] and Bauer,[268] bribery was not a significant factor in the two-year hiatus in deportations from Slovakia. However, Bauer acknowledges that the bribing of Wisliceny may "have helped to solidify an already existing tendency".[269] Bauer notes that most of the Jews not exempt from deportation had already been deported or fled into Hungary; the halt in deportations on 1 August 1942 came shortly after several Slovak officials (including Morávek) had accepted bribes from the Working Group, while Wisliceny did not receive a bribe until 17 August.[lower-alpha 12] American historian Randolph L. Braham argues that Wisliceny "played along" with negotiations and collected the Jews' money but in fact played an active role in the deportations.[271] More cautiously, German historian Peter Longerich writes: "It remains unresolved if [the payment to Wisliceny] had any causal connection with the suspension of deportations from Slovakia".[272]

Fatran[106][134] and Paul R. Bartrop[273] emphasize the role of the Working Group in distributing reports of Nazi atrocities to Slovak leaders, who backpedaled on deportations in late 1942. Braham credits a mix of factors: the request to visit "Jewish settlements" in Poland, bribing of Slovak officials, the protection of the remaining Jews under Slovak exemption policy, and lobbying by the Catholic Church.[274] According to Rothkirchen, there were three roughly equal factors: the Working Group's activities, pressure from the Vatican, and the growing unpopularity of deportations among gentile Slovaks (who witnessed the Hlinka Guard's violence in rounding up Jews).[275][lower-alpha 13] Longerich credits the shift in public opinion as the decisive factor, although the Working Group played "a significant role".[6] Aronson says that the halt was due to a complicated mix of domestic political factors, bribes for Slovak officials who organized transports, the Catholic Church's intervention, and implementation of the Final Solution in other countries.[266][267] According to Ivan Kamenec, diplomatic pressure from the Vatican and the Allies and internal pressure, including the visible brutality of the deportations, combined to halt the transports. Kamenec emphasizes the economic aspect; the deportations harmed the economy, and the remaining Jews were in economically useful positions.[278]

Nazi Germany put increasing pressure on the Slovak State hand over its remaining Jews in 1943 and 1944, but Slovak politicians did not agree to resume the deportations.[279] Rothkirchen and Longerich emphasize the role of the defeat at Stalingrad in crystallizing popular opinion against the Nazis and preventing the resumption of the deportations,[232][257] while Bauer credits the Working Group's bribery of Slovak officials.[187] Fatran identifies the Working Group's efforts to spread news of mass death and the increasing pressure of the Catholic Church as the main factors, along with fascist politicians' fears that they would be tried for war crimes if the Axis was defeated.[104][157] Fatran notes that property confiscation and deportation did not bring the prosperity promised by antisemitic politicians.[134] According to Kamenec, the transports were not resumed due to the detrimental effect of anti-Jewish measures on the economy and strong diplomatic pressure from the Vatican and the Allies.[280]

Feasibility of the Europa Plan

It is unlikely that the Nazis would have been willing to compromise on the implementation of the Final Solution for any price that the Jews could raise and illegally transfer.[lower-alpha 14] Friling and Bauer agree that the Nazis were willing to temporarily spare about 24,000 Slovak Jews in 1942 because other populations of Jews could be exterminated with fewer political repercussions.[269][282][lower-alpha 15] However, Friling doubts that a larger-scale ransom effort could have succeeded. As a personal bribe to Himmler or other Nazi officials, it would have had little effect on the complicated bureaucracy of the Nazi murder apparatus. The Europa Plan's cost per head was exponentially lower than other Jewish ransom efforts in Transnistria[lower-alpha 16] and the Netherlands,[lower-alpha 17] making it a bad deal from the Nazi perspective.[285][282] Fatran dismisses the plan as "unrealistic", and argues that the Nazis might be willing to release individuals for high ransoms, but not a large number of Jews.[286]

Friling suggests that Wisliceny probably devised the scheme to extort money from the Jews, and had no intention of keeping his side of the agreement.[287] According to Bauer, Himmler approved the opening of negotiations in November 1942 but they "lacked a concrete basis" because Wisliceny received no further instructions.[156] According to Bauer and Longerich, Himmler's goal was to negotiate with the Americans through the Jews.[272][156] Rothkirchen thinks this is possible but unproven, and suggests that the Nazis intended to influence popular opinion in the free world and discredit reports of the Final Solution (which were reaching the Allies). She notes that Himmler's decision to suspend negotiations in September 1943 coincided with the arrest of Carl Langbehn, who was trying to negotiate a separate peace with the Western Allies on Himmler's behalf.[288][289][290] Aronson says that the negotiations might have been coordinated with antisemitic propaganda broadcasts to the West, which depicted the war as being fought on behalf of Jews.[291] Braham considers Wisliceny to have been "advancing the interests of the SS" by extorting money from Jews while continuing to participate in the Final Solution.[292] The Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos states that "the Reich’s representatives were using the negotiations merely as a means of delay and personal enrichment".[44]

Other perspectives

Weissmandl and Fleischmann believed that the Europa Plan failed because too little money was provided too late, due to the indifference of mainstream Jewish organizations. Perhaps influenced by antisemitic conspiracy theories exaggerating the wealth and power of "world Jewry", Fleischmann and Weissmandl believed that the international Jewish community had millions of dollars readily available.[293] Slovak Jewish leaders did not understand the impact of Allied currency restrictions,[270][294] and tended to "take Wisliceny's statements at face value";[lower-alpha 18] Weissmandl wrote that he suspected the negotiations to be a sham only in 1944.[295][296][lower-alpha 19] Aronson describes Weissmandl's belief that deportations from Slovakia had ceased due to bribes paid to Wisliceny as "completely detached from historical reality".[267] According to Bauer, "The effect of this false rendition of events on Jewish historical consciousness after the Holocaust was enormous, because it implied that the outside Jewish world, nonbelievers in the non-Zionist and Zionist camps alike, had betrayed European—in this case Slovak—Jewry by not sending the money in time."[269] After the war, Weissmandl accused the Jewish Agency, the JDC, and other secular Jewish organizations of deliberately abandoning Jews to the gas chambers.[298][176] Weissmandl's accusations, which supported Haredi claims that Zionists and secularists were responsible for the Holocaust, became a cornerstone of the Haredi "counter-history". For ideological reasons, his collaboration with Fleischmann—a woman and a Zionist—was minimized or omitted.[299][300][291] Many Haredi writers take Weissmandl's allegations at face value, claiming that mainstream scholars are influenced by unconscious pro-Zionist bias.[301]

Repeating claims made by Rudolf Vrba, Canadian historian John S. Conway published two articles[lower-alpha 20] in Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, a German-language academic journal, in 1979 and 1984.[302][303] The first article was based on the false premise that Lenard had escaped from Majdanek in April 1942, and information on the mass murder of Jews in gas chambers was available to the Working Group by the end of the month. In both articles, Conway said that the Working Group collaborated with the Nazis by negotiating with Wisliceny and failing to distribute the Vrba-Wetzler report to Jews in Slovakia. Their alleged motivation was to cover up the complicity of group members who had drawn up lists of Jews to be deported[304][305] and to save itself or its members' "close friends", a claim for which Conway does not cite any evidence.[306][307] Fatran criticized Conway's thesis for its selective reliance on a few pieces of evidence which were mistranslated or misinterpreted, describing his argument that the Working Group collaborated with the Nazis as "speculative and unproven";[308] Bauer deems this idea "preposterous".[309] Erich Kulka criticized Vrba's and Conway's "distorted statements" about the Working Group, which had hidden Vrba after his escape.[310][lower-alpha 21] Conway accused mainstream Israeli historians who studied the Working Group of yielding to Zionist establishment pressure and promoting a "hegemonic narrative".[314]

References

Notes

- Pracovná Skupina is Slovak for "Working Group".[1][2] Alternate names were Nebenregierung (German), referring to a "shadow government" within the official Jewish Center,[3][4][5] and Vedlejši Vlada[1] (Slovak for "subsidiary government"[6] or "Alternative Government"). Weissmandl used a Hebrew name, Hava'ad Hamistater, "Hidden Committee".[1][2]

- Mentioned on the plaque, in order, are Gisi Fleischmann, Tibor Kováč, Armin Frieder, Andrej Steiner, Oskar Neumann, Wilhelm Fürst, and Michael Dov Weissmandl.

- Slovak Jews who had come of age under Austro-Hungarian rule spoke German or Hungarian as their primary language; most were not fluent in Slovak.[22][23][21]

- Yehuda Bauer,[31] Mordecai Paldiel,[2] Livia Rothkirchen, David Kranzler,[42] and Katarína Hradská[40] agree on this point.

- Estimates vary widely because the illegal crossings were not officially recorded.[88] Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka (2018, p. 847) gave the figure of 5,000–6,000. In 1992 and 2011, Slovak historian Ivan Kamenec stated that 6,000 Jews escaped to Hungary.[89][90] Bauer (1994, pp. 73–74) stated that 8,000 had escaped; in 2002 he revised this figure to 7,000.[31] In 1992, Fatran estimated that 5,000–6,000 Jews crossed the border,[85] but four years later she changed this estimate to 10,000.[88] According to Kamenec, most of those who were successful in crossing the border bribed the guards to let them through.[90]

- About 2,500 people were living in the camps on 1 January 1943.[58] Although most sources describe the efforts to discourage deportation via the labor camps as being run by the ÚŽ—see Kamenec (2002, p. 134), Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka (2018, p. 848)—Rothkirchen[37][136] attributes them to the Working Group. Bauer notes that the camps may have "played into the hands of the Nazis" by facilitating deportations after the 1944 invasion.[137]

- According to Weissmandl's memoirs, the dollar bills were steam ironed in order to make it appear that they had been recently issued by a foreign bank.[138]

- According to the Slovak police records, Hochberg had an illegal account in which large bribes were deposited in return for the cessation of transports.[141]

- Israeli historian Shlomo Aronson notes that an 11 August meeting of Slovak officials concluded that further deportations would cripple the economy.[143]

- Andrej Steiner, a member of the Working Group, distrusted Hochberg and had provided the Slovak police with evidence against him. However, Weissmandl advocated that the Working Group try to get him released; he believed that Hochberg was useful and was concerned that he would reveal the negotiations. Fleischmann sided with Steiner, and the Working Group did not intervene on Hochberg's behalf.[153]

- For instance, in early September two transports, carrying 5,007 people, left Theresienstadt for Auschwitz despite Nazi promises not to deport any more Jews from the ghetto.[183]

- In Wisliceny's postwar testimony, he claimed that he first heard about the plan to kill all Jews at the beginning of August. Bauer alleges that this may have influenced his behavior,[269] but Rothkirchen asserts that Wisliceny distorted his chronology in order to claim that he had not known about the Final Solution earlier.[270]

- According to Ivan Kamenec, the brutality of the deportation of families in April and May caused many Slovaks to doubt the purportedly Christian character of the regime.[276] In June, the German ambassador to Slovakia, Hanns Ludin, reported that popular opinion in Slovakia had turned against the deportations, because gentile Slovaks witnessed the violence used by the Hlinka Guard against Jews.[232] Rothkirchen also highlights the role of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile and the BBC in publicizing reports of atrocities.[277]

- Bauer points out that the Nazis explicitly defined the war as a "race war"; to halt the war of extermination for practical reasons would remove their casus belli.[281] In Friling's words, compromise on the Final Solution "totally contradicted Nazi ideology".[282]

- This analysis is supported by a Nazi missive in summer 1942 advising against insisting upon the deportation of the remaining Slovak Jews.[156]

- At one point, the sum of $400 per head was suggested for the ransom of Jews in the Transnistria Governorate. Despite the potential for financial gain, the Nazis sabotaged offers of ransom in Transnistria and for Jewish children in the Balkans.[282]

- With Hitler's permission, a few Dutch Jews were allowed to leave occupied Europe after paying large sums of foreign currency. The vast majority of offers were rejected, and ultimately 28 Jews were allowed to emigrate for the average payment of some 50,000 – 100,000 Swiss francs per head.[283][284]

- In Rothkirchen (1984, p. 9)'s words. Bauer (1994, p. 100) writes, "What is amazing is that the highly intelligent Slovak Jewish leaders believed [Wisliceny] and trusted him more than they did their colleagues outside the Nazi empire, and none more so than Weissmandel. He did not trust Schwalb or Mayer, but he did trust a Nazi."

- In one of his letters to Switzerland, Weissmandl wrote, "We must accept premise No. 1, in theory and practice—that their intentions are honest in this matter... Premise No. 2: ... All this is a plot, a maneuver, a gesture of camouflage which they have undertaken to win our confidence, to undermine our already meager and paltry power to resist them... Though we must operate on the basis of premise No. 1 in our posture and money, we must also confront premise No. 2."[297]

-

- Conway, John S. (1979). "Frühe Augenzeugenberichte aus Auschwitz. Glaubwürdigkeit und Wirkungsgeschichte". Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (in German). 27 (2): 260–284. JSTOR 30197260.

- Conway, John S. (1984). "Der Holocaust in Ungarn. Neue Kontroversen und Überlegungen" (PDF). Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (in German). 32 (2): 179–212. JSTOR 30195267.

- Bauer notes that, of the Slovak Jewish leaders, only Hochberg assisted with deportations (and did not draw up deportation lists),[140][28] while Working Group members orchestrated his arrest.[311] Contradicting Conway's assertions, the Working Group, Orthodox organizations and the Zionist youth movements advised Jews to flee to Hungary and helped smuggle them across the border even before news of systematic extermination was available.[312][304][100] Kamenec said that Conway had misinterpreted some passages in his monograph On the Trail of Tragedy, possibly due to his inability to understand Slovak.[313]

Citations

- Bauer 1994, p. 74.

- Paldiel 2017, p. 103.

- Fatran 2002, p. 146.

- Kamenec 2007, p. 230.

- Kubátová 2014, p. 513.

- Longerich 2010, p. 326.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, p. 843.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, p. 844.

- Fatran 2002, pp. 141–142.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, pp. 844–845.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, pp. 842–843.

- Kamenec 2002, pp. 111–112.

- Rothkirchen 2001, p. 597.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, p. 846.

- Fatran 2002, p. 144.

- Fatran 1994, p. 165.

- Kamenec 2002, p. 114.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, p. 845.

- Bauer 2002, p. 176.

- Fatran 2002, pp. 143–144.

- Fatran 1994, p. 166.

- Bauer 1994, pp. 83–84.

- Bauer 2002, p. 172.

- Fatran 2002, pp. 144–145.

- Bauer 1994, p. 70.