Sobibor extermination camp

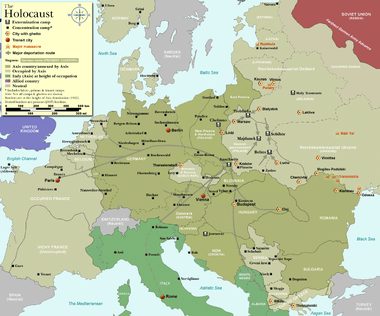

Sobibor (/soʊˈbiːbɔːr/) was an extermination camp built and operated by Nazi Germany as part of Operation Reinhard. It was located in the forest near the village of Sobibór in the General Government region of German-occupied Poland.

| Sobibor | |

|---|---|

| Extermination camp | |

.jpg) Sobibor extermination camp view, summer 1943 | |

| Other names | SS-Sonderkommando Sobibor |

| Known for | Genocide during the Holocaust |

| Location | Near Sobibór, General Government (occupied Poland) |

| Built by |

|

| Commandant |

|

| First built | October 1941 – May 1942 |

| Operational | 16 May 1942 – 14 October 1943[1] |

| Inmates | Jews, mainly from Poland |

| Number of inmates | 600–650 slave labour at any given time |

| Killed | At least 170,000–250,000 |

| Notable inmates | List of survivors of Sobibor |

As an extermination camp rather than a concentration camp, Sobibor existed for the sole purpose of killing Jews. The vast majority of prisoners were gassed within a few hours of their arrival. Those not gassed immediately were forced to assist in the operation of the camp and most died or were killed in turn within a few months. In total, some 170,000 to 250,000 people were murdered at Sobibor, making it the fourth-deadliest Nazi camp after Belzec, Treblinka, and Auschwitz.

The camp ceased operations after the prisoner revolt, which took place on 14 October 1943. The plan for this revolt involved two phases. In the first phase, teams of prisoners were to assassinate all of the SS officers separately. In the second phase, all 600 prisoners would assemble for roll call and walk to freedom out the front gate. However, the plan was disrupted after only 12 of the SS officers had been killed. The prisoners had to escape by climbing over barbed wire fences and running through a mine field under heavy machine gun fire. About 300 prisoners made it out of the camp, of whom at least 58 survived the war.

After the revolt, the Nazis demolished the camp and planted it over with pine trees. The site was neglected in the first decades after World War Two, and the camp itself had little presence in either popular or scholarly accounts of the Holocaust. It became better known after it was portrayed in the United States TV miniseries Holocaust (1978) and the British TV film Escape from Sobibor (1987). After the fall of the Soviet Union, the Sobibor Museum opened at the site, and archaeologists began excavations which continue as of 2020. In 2020, the first photographs of the camp in operation were published as part of the Sobibor perpetrator album.

Background

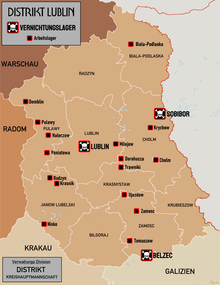

Following the invasion of Poland in 1939, the Germans began implementing the Nisko Plan. Jews were deported from ghettos across Europe to labor camps in Lublin District, a region chosen for its inhospitable conditions.[2] The Nisko Plan was abandoned in 1940, but a number of these so-called Lublin Reservation camps remained in use until 1943 or later, including several near Sobibor.

In 1941, the Nazis began experimenting with gassing Jews. In December 1941, officials at Chełmno experimented with using gas vans to kill Jews and reduce overcrowding in the Łódź Ghetto.[3] In early January, the first mass gassings were conducted at Auschwitz concentration camp. At the Wansee Conference on 20 January 1942, Reinhard Heydrich announced a plan for systematically exterminating the Jews through a system of death camps.[4] This plan was realized as Operation Reinhard, the deadliest phase of the Holocaust. Sobibór was one of the four extermination camps established as part of Operation Reinhard.[5]

Establishment

Camp construction

Nothing is known for certain about the early planning for Sobibor.[7] Some historians have speculated that planning may have begun as early as 1940, on the basis of a railway map from that year which omits several major cities but includes Sobibór and Bełżec.[8] The earliest hard evidence for Nazi interest in the site comes from the testimony of local Poles, who noticed in Autumn 1941 that SS officers were surveying the land opposite the train station.[9] When a worker at the station cafeteria asked one of the SS men what was being built, he replied that she would soon see and that it would be "a good laugh."[10]

Construction was supervised by SS-Hauptsturmführer Richard Thomalla, a civil engineer by profession, who had previously built the Bełżec extermination camp.[11] The first workers ordered to build the railroad spur were local people from neighbouring villages and towns, who worked from late 1941 to March 1942.[12] The full camp was primarily built by a work detail of about eighty Jews from ghettos within the vicinity of the camp. Most of these Jews were killed upon completion of construction, but two escaped to nearby Włodawa, where they attempted to warn the town's Jewish council about the camp and its purpose. Their warnings were met with disbelief.[13][14]

Erich Fuchs acquired a heavy gasoline engine in Lemberg, disassembled from an armoured vehicle or a tractor: a 200 horsepower, V-shaped, 8 cylinder, water-cooled motor, identical to the one at Bełżec. Fuchs installed the engine on a cement base at Sobibor in the presence of SS officers Floss, Bauer, Stangl, and Barbl, and connected the engine exhaust manifold to pipes leading to the gas chamber.[15]

In mid-April 1942, the Nazis conducted experimental gassings in the nearly finished camp. Christian Wirth, the commander of Bełżec and Inspector of Operation Reinhard, visited Sobibor to witness one of these gassings, which killed thirty to forty Jewish women brought from Krychów for this purpose.[16] He reportedly complained about the fitting of the gas chambers' doors. Some 250 Jews from Krychów were killed during these trials.[17]

At the end of April 1942, SS-Obersturmführer Franz Stangl, a high-ranking SS official, arrived at Sobibor to serve as its first commandant.[18] He was appointed by Heinrich Himmler due to his experience in the T-4 Euthanasia Program as deputy office manager at both the Hartheim and Bernburg extermination hospitals.[19]

Layout

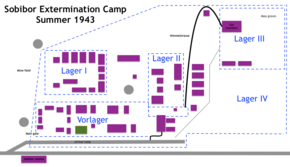

Sobibor was divided into five compounds: the Vorlager and four Lagers numbered I-IV. The Vorlager (front compound) contained living quarters and recreational buildings for the camp personnel. The SS officers lived in cottages with colorful names such as Lustiger Floh (The Merry Flea), Schwalbennest (The Swallow’s Nest), and Gottes Heimat (God’s Own Home).[20] They also had a canteen, a bowling alley, a hairdresser, and a dentist, all staffed by Jewish prisoners.[21][22] The watchmen (Trawniki men), drawn from Soviet POWs, had separate barracks, and their own separate recreational buildings, including a hair salon and a canteen.[23]

The Nazis paid great attention to the appearance of the Vorlager. It was neatly landscaped, with lawns and gardens, outdoor terraces, gravel-lined paths, and professionally painted signs.[24] This idyllic appearance helped hide the nature of the camp from prisoners, who would arrive on the adjacent ramp. Survivor Jules Schelvis recalled feeling reassured upon arrival by the Vorlager's "Tyrolean cottage-like barracks with their bright little curtains and geraniums on the windowsills".[25]

Lager I contained barracks and workshops for the prisoners.[26] These workshops included a tailor's shop, a carpenter's shop, a mechanic's shop, a sign-painter's shop, and a bakery.[27] [28] Lager I was accessible only through the adjacent Vorlager, and its western boundary was made escape-proof with a water-filled trench.[29]

Lager II was a larger multi-purpose compound. One subsection called the Erbhof contained the administration building, as well as a small farm.[30] The administration building was a pre-war structure previously used by the local Polish forestry service.[21] As part of the camp, this building was adapted to provide accommodation for some SS officers, storage for goods stolen from victims' luggage, as well as a pharmacy, whose contents were also taken from victims' luggage[31][21] On the farm, Jewish prisoners raised chickens, pigs, geese, fruits and vegetables for consumption by the SS men.[30]

Outside the Erbhof, Lager II contained facilities where new arrivals were prepared for their deaths. It contained the sorting barracks and other buildings used for storing items taken from the victims, including clothes, food, hair, gold, and other valuables.[28] At the east end was a yard where new arrivals had their luggage taken from them and were forced to undress. This area was beautified with flower beds to hide the camp's purpose from newcomers.[32][33] This yard led into the narrow enclosed path called the Himmelstrasse (road to heaven) or the Schlauch (tube), which led straight to the gas chambers in Lager III.[34][35] The Himmelstrasse was covered on both sides by fences woven with pine branches.[34]

Lager III was the extermination area. It was isolated from the rest of the camp, set back in a clearing in the forest and surrounded by its own thatched fence.[36] Prisoners from Lager I were not allowed near it, and were killed if they were suspected of having seen inside.[37][38][39] Due to a lack of eyewitness testimony, little is known about Lager III beyond the fact that it contained gas chambers, mass graves, and special separate housing for the sonderkommando prisoners who worked there.[37][40][41]

Lager IV (also called the Nordlager) was added in July 1943, and was still under construction at the time of the revolt. Located in a heavily wooded area to the north of the other camps, it was being developed as a munitions depot for processing arms taken from Red Army soldiers.[42][43][44]

Life in the camp

Prisoner life

Because Sobibor was an extermination camp, the only prisoners who lived there were the roughly 600 slave labourers forced to assist in the operation of the camp.[45] While survivors of Auschwitz use the term “selected” to mean being selected for death, at Sobibor being “selected” meant being selected to live, at least for a while.[46] The harsh conditions in the camp took the lives of most new arrivals within a few months.[47]

Work

Prisoners worked from 6am to 6pm six days a week, with a short lunch break in the middle. Officially, Sundays were half days, with the remainder of the day spent cleaning and resting. However, this tradition was not always respected.[48][49] Prisoners with specialized skills worked as goldsmiths, sign painters, gardeners, shoemakers, and tailors. While their labor camp was intended to support the functioning of the camp, much of it was diverted to enrich the SS officers. For instance, Max van Dam and Moredechai Goldfarb were nominally sign painters, but SS officers also forced them to paint landscapes, portraits, and hagiographic images of Hitler.[50][51] Similarly, 14 year old Shlomo Szmajzner was placed in charge of the machine shop in order to conceal his true job which was making gold medallions and jewelry for SS officers.[52] Because these prisoners were considered valuable, they were afforded special privileges and were less likely to be beaten or killed by the guards.[53]

Those without specialized skills performed a variety of other jobs. In Lager II, many worked in the sorting barracks, combing through the belongings of killed in the gas chambers and packaging those things which were in good condition so they could be sent to German civilians disguised as “charity gifts”.[54] These workers could also be called on to work in the railway brigade, where they helped unload arriving prisoner transports. The railway brigade was considered a relatively appealing job, since it gave famished workers access to luggage which was often full of food.[55] A particularly horrifying job was that of the “barbers” who cut the hair of women who were about to be gassed. This job was often forced upon young male prisoners in an attempt to humiliate both them and the naked women whose hair they were cutting. Armed guards supervised the process in order to ensure that barbers did not respond to victims' questions or pleas.[56]

In Lager III, a special unit of Jewish prisoners was forced to assist in the extermination process. Its tasks included removing bodies, searching cavities for valuables, scrubbing blood and excrement from the gas chambers, and cremating the corpses. Because the prisoners who belonged to this unit were direct witnesses to genocide, they were strictly isolated from other prisoners and the Nazis would periodically liquidate those unit members who hadn't already succumbed to the work's physical and psychological toll. Since no workers from Lager III survived, nothing is known about their lives or experiences.[57]

Prisoners struggled with the fact that their labor made them complicit in mass murder, albeit indirectly and unwillingly.[58] Many committed suicide.[59][60] Others endured, finding ways to resist, if only symbolically. Common symbolic forms of resistance included praying for the dead, observing Jewish religious rites, [60] and singing songs of resistance.[61] However, some prisoners found small ways of materially fighting back. For instance, while working in the sorting shed, Saartje Wijnberg would surreptitiously damage fine items of clothing to prevent them from being sent to Germany.[62] After the war, Esther Terner recounted what she and Zelda Metz did when they found an unattended pot of soup in the Nazis' canteen: "We spit in it and washed our hands in it… Don't ask me what else we did to that soup… And they ate it."[63]

Social relations

Because of the constant turnover in the camp population, many prisoners found it difficult to forge personal relationships.[47] Moreover, prisoners were disinclined to trust one another, especially when divided by culture or language.[64] The camp's minority of Dutch Jews were subject to derision and suspicion because of their assimilated manners and limited understanding of Yiddish.[65] German Jews faced these barriers as well, with the added implication that they might identify more with their captors than with their fellow prisoners.[66] Thus, when groups did form, they were generally based on family ties or shared nationality, and were completely closed off to outsiders.[64] Chaim Engel even found himself shunned by fellow Polish Jews after he began a romantic relationship with Dutch-born Saartje Wijnberg.[67] These divisions had dire consequences for many Western Jews, who were not trusted with crucial information about goings-on in the camp. In particular, the Polish and Russian organizers of the revolt deemed it necessary to restrict to knowledge of their plan until the last moment. As a result, despite their best efforts, almost none of the western prisoners survived.[68]

Because of the expectation of imminent death, prisoners adopted a day-at-a-time outlook. Crying was rare[64] and evenings were often spent enjoying whatever of life was left. As revolt organizer Leon Feldhendler recounted after the war, “The Jews only had one goal: carpe diem, and in this they simply went wild.”[69] Prisoners sang and danced in the evenings[70] and sexual or romantic relations were frequent.[71] Some of these affairs were likely transactional, especially those between female prisoners and kapos, but others were driven by genuine bonds.[72] (For instance, Saartje Wijnberg and Chaim Engel were married after the war.[72]) The Nazis allowed and even encouraged an atmosphere of merriment, going so far as to recruit prisoners for a choir at gunpoint.[73] Many prisoners interpreted these efforts as attempts by the Nazis to keep the prisoners docile and to prevent them from thinking about escape.[74]

Prisoners had a pecking order largely determined by one's usefulness to the Germans. As survivor Toivi Blatt observed, there were three categories of prisoners: the expendable “drones” whose lives were entirely at the mercy of the SS, the privileged workers whose special jobs provided some relative comforts, and finally the artisans whose specialized knowledge made them indispensable and earned them preferential treatment.[53] Moreover, as at other camps, the Nazis appointed kapos to keep their fellow prisoners in line.[75] Kapos carried out a variety of supervisory duties and enforced their commands with whips.[76] Kapos were involuntary appointees, and they varied widely in how they responded to the psychological pressures of the job. Oberkapo Moses Sturm was nicknamed "Mad Moisz" for his mercurial temperament. He would beat prisoners horrifically without provocation and then later apologize hysterically. He talked constantly of escape, sometimes merely berating the other prisoners for their inaction, other times proposing serious plans. Sturm was executed by the Nazis after one of his escape plans was betrayed by a lower ranking kapo named Herbert Naftaniel who was subsequently promoted to Oberkapo.[77] Naftaniel, nicknamed "Berliner", became a notorious figure in the camp. He viewed himself as German rather than Jewish, and took initiative in finding reasons to harass, spy on, and beat prisoners. His reign of terror came to an end after he attempted to override an order from SS-Oberscharfuhrer Karl Frenzel to increase rations for the railway brigade. With Frenzel's permission, a group of prisoners beat Berliner to death.[78]

Despite these divisions in the camp, prisoners found ways to support each other. Much of this support went to sick or injured prisoners, who were given clandestine food[79][80] as well as medicine and sanitary supplies stolen from the camp pharmacy.[81] Healthy prisoners would often take over the jobs of sick prisoners who would have been killed by the guards for not performing their duties[79] and the camp nurse Kurt Ticho regularly falsified his records to allow prisoners more than the allotted three day recovery period.[82] Prisoners sometimes attempted to rescue others from the gas chambers, but were not in general successful. For instance, members of the railway brigade attempted to warn newly arrived prisoners of their impending murder but were met with incredulity.[83] The most successful act of solidarity in the camp was the revolt on 14 October 1943, which was expressly planned so that all of the prisoners in the camp would have at least some chance of escape.[84]

Health and living conditions

Prisoners suffered from poor health due to sleep deprivation, malnourishment, stress, and the physical and emotional toll of grueling labour and constant beatings.[69][85] Lice, skin infections, and respiratory infections were common,[86] and typhoid swept the camp on at least one occasion.[87] In the first months after Sobibor opened, prisoners were regarded as easily replaceable and were shot at the first sign of illness or injury.[85] This policy resulted in such a high death rate that the constant training of new workers began to reduce the camp's efficiency. In order to increase the continuity of its labour force, the SS officers instituted a policy allowing incapacitated prisoners three days to recover. Prisoners who were still unable to work after three days were shot.[88][82]

Food in the camp was extremely limited. As at other Lublin district camps, prisoners were given about 200 grams of bread for breakfast along with ersatz coffee. Lunch was typically a thin soup sometimes with some potatoes or horse meat. Dinner could be once again simply coffee.[89] Prisoners found their personalities changing due to their constant hunger.[55] To make up for these insufficient rations, prisoners would find food other ways. Those working in the forest could smuggle mushrooms back into the camp.[90] Those working in the sorting barracks or the railway brigade would help themselves either to food or else to valuables which could be traded for food.[72] A barter system developed in the camp, which included not only prisoners but also the watchmen, who could serve as intermediaries between the Jews and local peasants, exchanging jewels and cash for food and liquor in exchange for a large cut.[91][92]

Most prisoners had little or no access to hygiene and sanitation. There were no showers in the prisoners’ living quarters and clean water was scarce.[93] Although clothing could be washed or replaced from the sorting barracks, the camp was so thoroughly infested that there was little point.[94] However, some prisoners worked in areas of the camp such as the laundry which gave them occasional access to better hygiene.[95]

Relations with the perpetrators

Prisoners lived in constant fear of SS officers, who used extreme violence to enforce not only the official camp rules but also their own personal whims.[96] Prisoners were punished for transgressions as inconsequential as smoking a cigarette,[96] resting while working,[75] and showing insufficient enthusiasm when forced to sing.[49] The most common punishment was flogging. SS officers carried 80 centimeter whips which had been specially made by slave labor prisoners using leather taken from the luggage of gas chamber victims.[97] Even when flogging wasn't in itself lethal, it would prove a death sentence if it left the recipient too injured to work.[98] The SS officers also used dogs to punish prisoners. In particular, many survivors remember an unusually large and aggressive St. Bernard named Barry who Kurt Bolender and Paul Groth would sic on prisoners.[99][100] In the summer of 1943, SS-Oberscharfuhrer Gustav Wagner and SS-Oberscharfuhrer Hubert Gomerski formed a penal brigade, consisting of prisoners who were forced to work while running. Prisoners were assigned to the penal brigade for a period of three days, but most died before their time was up.[101][102]

Prisoners developed complex relationships with their tormenters. In order to avoid the most extreme cruelties, many tried to ingratiate themselves with the SS officers,[103] for instance by choosing maudlin German folk songs when ordered to sing.[104] In other cases, prisoners found themselves unwillingly favored. SS-Oberscharfuhrer Karl Frenzel took a liking to Saartje Wijnberg, constantly smiling at her and teasingly referring to her and Chaim Engel as "bride and groom".[65] He was protective towards her, excusing her from torturous work inflicted on other Dutch prisoners[105] and sparing her when he executed all of the other sick prisoners on 11 October 1943.[106] She struggled with this attention and felt angry at herself when she noticed that she was grateful to him.[65] At his trial, Frenzel declared "I actually do believe the Jews even liked me!" [107] though both prisoners and other SS officers regarded him as exceptionally cruel and brutal.[108] Similarly, camp kommandant SS-Obersturmführer Franz Stangl "made a pet" of the 14 year old goldsmith Shlomo Szmajzner and regarded his post-war trial testimony as a personal betrayal. In particular, Stangl objected to the implication that his habit of bringing Smajzner sausages on the sabbath had been a deliberate attempt to torment the starving teenager. Szmajzner himself wasn't sure of Stangl's intentions: "it's perfectly true that he seemed to like me… still, it was funny, wasn't it, that he always brought it on a Friday evening?" [109]

Camp personnel

The personnel at Sobibor included a small cadre of German and Austrian SS Officers, and a much larger group of Soviet POWs called watchmen or Trawniki men.[110]

SS garrison

Sobibor was staffed by a rotating group of eighteen to twenty-two German and Austrian SS officers.[111] When Sobibor first opened, its kommandant was SS-Obersturmführer Franz Stangl, a meticulous organizer who worked to increase the efficiency of the extermination process.[112][29] Stangl had little interaction with the prisoners,[113] with the exception of Shlomo Szmajzner who recalled Stangl as a vain man who stood out for "his obvious pleasure in his work and his situation. None of the others --although they were, in different ways, so much worse than he-- showed this to such an extent. He had this perpetual smile on his face."[114] Stangl was transferred to Treblinka in August 1942, and his job at Sobibor was filled by SS-Obersturmführer Franz Reichleitner. Reichleitner was an alcoholic and a determined anti-semite who took little interest in what went on in the camp aside from the extermination process.[115][116] SS-Untersturmführer Johann Niemann served as the camp's deputy kommandant.[117][118]

Day-to-day operations were generally handled by SS-Oberscharfuhrer Gustav Wagner, the most feared and hated man in Sobibor. Prisoners regarded him as brutal, demanding, unpredictable, observant, and sadistic. They referred to him as "The Beast" and "Wolf".[119][120] Reporting to Wagner was SS-Oberscharfuhrer Karl Frenzel, who oversaw Lager I and acted as the camp's "judicial authority".[121] Kurt Bolender and Hubert Gomerski oversaw Lager III, the extermination area,[122][123] while SS-Oberscharfuhrer Erich Bauer and ''SS-Scharführer'' Josef Vallaster typically directed the gassing procedure itself.[124][125]

The SS officers were all German or Austrian men, generally from lower-middle class backgrounds. Many had previously worked as merchants, artisans, farmhands, nurses, and policemen.[126] Most had previously served in Aktion T4, the Nazi forced euthanasia program. In particular, a large contingent had previously served together at Hartheim Euthanasia Centre. Many practices developed at Hartheim were continued at Sobibór, including methods for deceiving victims on the way to the gas chambers.[127]

The SS officers exercised absolute authority over the prisoners and treated them as a source of entertainment.[128] They forced prisoners to sing while working, while marching, and even during public executions.[129] Some survivor testimonies recount prisoners performing mock cockfights for the SS, with their arms tied behind their backs. Others recount being forced to sing demeaning songs such as "I am a Jew with a big nose".[130] Female prisoners were sexually abused on several occasions. For instance, at a postwar trial, Erich Bauer testified that two Austrian Jewish actresses, named Ruth and Gisela, were confined in the SS barracks for sex. They were gang raped by SS men, including SS-Oberscharfuhrer Kurt Bolender and SS-Oberscharfuhrer Gustav Wagner.[131]

The SS men considered their job appealing. At Sobibor, they could enjoy creature comforts not available to soldiers fighting on the Eastern Front. The officer's compound in the camp had a canteen, a bowling alley, and a barber shop. The "officers' country club" was a short distance away, on nearby Perepsza Lake.[126] Each SS man was allowed three weeks of leave every three months, which they could spend at Haus Schoberstein, an SS-owned resort in the Austrian town of Weissenbach on Lake Attersee.[133] Moreover, the job could be lucrative: each officer received base pay of 58 Reichmarks per month, plus a daily allowance of 18 marks, and special bonuses including a Judenmordzulage (Jew murder supplement). In all, an officer at Sobibor could earn 600 marks per month in pay.[128] In addition to the official compensation, a job at Sobibor offered endless opportunities for the SS officers to covertly enrich themselves by exploiting the labor and stealing the possessions of their victims. In one case, the SS officers enslaved a 15-year-old goldsmith prodigy named Shlomo Szmajzner, who made them rings and monograms from gold extracted from the teeth of gas chamber victims.[134]

Watchmen

Sobibor was guarded by approximately 400 Trawniki men, or watchmen.[135] Survivors often refer to them as blackies, Askaris, or Ukrainians (even though many were not Ukrainian). They were captured Soviet prisoners of war who had volunteered for the SS in order to escape the abominable conditions in Nazi POW camps.[136][137] Watchmen were nominally guards, but they were also expected to perform manual labor, supervise work details, and to punish or torture disobedient prisoners.[110] They also took an active part in the extermination process, unloading Jews from newly arrived transports, chasing them along the path to Lager III, and forcing victims into the gas chambers.[138][139] They made up the firing squads that executed sick or disobedient prisoners.[136]

Prisoners regarded the watchmen as the most dangerous among the Sobibor staff, their cruelty surpassing that of the SS officers.[136] In the words of historian Marek Bem, “It can be said that the Ukrainian guards’ cynicism was in no way inferior to the SS men's premeditation.” [141] However, their loyalty was not unwavering. Many took an active part in Sobibor’s underground economy, bartering with locals on behalf of Jewish prisoners in exchange for a cut.[91] They also drank copiously despite being prohibited from doing so.[142][143] The SS officers were wary of the watchmen, limiting the amount of ammunition they could carry[136] and transferring them frequently between different camps in order to prevent them from building up local contacts or knowledge of the surrounding area.[144] Moreover, some watchmen were sympathetic to the Jews, limiting their violence to the minimum possible and even assisting with prisoners’ escape attempts.[145] In one documented instance, watchmen Victor Kisiljow and Wasyl Zischer escaped with six Jewish prisoners, but were betrayed and killed.[146]

The contingent of watchmen was divided into platoons, each headed by a Volksdeutscher.[135] Watchmen did not have a standardized uniform— many were dressed in mixed-and-matched pieces of Nazi, Soviet, and Polish uniforms, often dyed black (giving rise to the term blackies’’).[135] They received pay and rations similar to those of Waffen-SS, as well as a family allowance and holiday leave.[147]

After the 1943 revolt, watchmen were not permitted to join in the search for the escapees, since the SS were afraid that they would desert. Instead, they were sent back to Trawniki.[148] However, during the march back to Trawniki, some deserted anyway. Watchman Wasyl Hetmaniec shot and killed the group’s escort, SS-Oberscharfuhrer Herbert Floss.[149][150]

Extermination

Killing process

On either 16 or 18 May 1942, Sobibor became fully operational and began mass gassings. Trains entered the railway siding with the unloading platform, and the Jews on board were told they were in a transit camp. They were forced to hand over their valuables, were separated by sex and told to undress. The nude women and girls, recoiling in shame, were met by the Jewish workers who cut off their hair in a mere half a minute. Among the Friseur (barbers) were Toivi Blatt (age 15).[151] The condemned prisoners, formed into groups, were led along the 100-metre (330 ft) long "Road to Heaven" (Himmelstrasse) to the gas chambers, where they were killed using carbon monoxide released from the exhaust pipes of a tank engine.[152] During his trial, SS-Oberscharführer Kurt Bolender described the killing operations as follows:

Before the Jews undressed, SS-Oberscharführer Hermann Michel made a speech to them. On these occasions, he used to wear a white coat to give the impression he was a physician. Michel announced to the Jews that they would be sent to work. But before this they would have to take baths and undergo disinfection, so as to prevent the spread of diseases. After undressing, the Jews were taken through the "Tube", by an SS man leading the way, with five or six Ukrainians at the back hastening the Jews along. After the Jews entered the gas chambers, the Ukrainians closed the doors. The motor was switched on by the former Soviet soldier Emil Kostenko and by the German driver Erich Bauer from Berlin. After the gassing, the doors were opened, and the corpses were removed by the Sonderkommando members.[153]

Local Jews were delivered in absolute terror, amongst screaming and pounding. Foreign Jews, on the other hand were treated with deceitful politeness. Passengers from Westerbork, Netherlands had a comfortable journey. There were Jewish doctors and nurses attending them and no shortage of food or medical supplies on the train. Sobibor did not seem like a genuine threat.[154]

The non-Polish victims included 18-year-old Helga Deen from the Netherlands, whose diary was discovered in 2004; the writer Else Feldmann from Austria; Dutch Olympic gold medalist gymnasts Helena Nordheim, Ans Polak, and Jud Simons; gym coach Gerrit Kleerekoper; and magician Michel Velleman.[155]

After the killing in the gas chambers, the corpses were collected by Sonderkommando and taken to mass graves or cremated in the open air.[156] The burial pits were approx. 50-60m (160–200 ft) long, 10-15m (30–50 ft) wide, and 5-7m (15–20 ft) deep, with sloping sandy walls in order to facilitate the burying of corpses.[17]

Death toll

Between 170,000 and 250,000 Jews were murdered at Sobibor. The precise death toll is unknown, since no complete record survives. The most commonly cited figure of 250,000 was first proposed in 1947 by a Polish judge named Zbigniew Łukaszewicz, who interviewed survivors, railwaymen, and external witnesses to estimate of the frequency and capacity of the transports. Later research has reached the same figure drawing on more specific documentation,[157] although other recent studies have given lower estimates such as Jules Schelvis's figure of 170,165.[158] According to historian Marek Bem, "The range of scientific research into this question shows how rudimentary our current knowledge is of the number of victims of this extermination camp."[159]

One major source which can be used to estimate the death toll is the Höfle Telegram, a collection of SS cables which give precise numbers of "recorded arrivals" at each of the Operation Reinhard camps prior to 31 December 1942. Identical numbers are found in the Korherr Report, another surviving Nazi document. These sources both report 101,370 arrivals at Sobibor during the year 1942,[160] but the meaning of this figure is open to interpretation. Some scholars such as Marek Bem suggest that it refers only to Jews arriving from within the General Government.[161] However, others such as Jules Schelvis take it as a record of the total arrivals during that year and thus combine it with an estimate of the killings in 1943 to reach a total estimate.[162]

Other key sources of information include records of particular transports sent to Sobibor. In some cases, this information is detailed and systematic. For instance, the Dutch Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies archive contains precise records of each transport sent to Sobibor from the Netherlands, totaling 34,313 individuals.[163] In other cases, transports are only known through incidental evidence, such as when one of its passengers was among the survivors.

Many of the difficulties in reaching a firm death toll arise from the incompleteness of surviving evidence. Records of deportations are more likely to exist when they took place by train, meaning that estimates likely undercount the number of prisoners brought on trucks, horse-drawn carts, or by foot.[164] Moreover, even records of trains appear to contain gaps. For example, while a letter from Albert Ganzenmüller to Karl Wolff mentions past trains from Warsaw to Sobibor, no itineraries survive.[165] On the other hand, estimates may count small numbers of individuals as Sobibor victims who in fact died elsewhere, or conceivably even survived. This is because small groups of new arrivals were occasionally selected to work in one of the nearby labor camps, rather than being gassed immediately as was the norm.[166] For instance, when Jules Schelvis was deported to Sobibor on a transport carrying 3,005 Dutch Jews, he was one of 81 men selected to work in Dorohucza, though the only one to survive.[167] Although these instances were rare and some are documented well enough to be accounted for, they could still have a small cumulative effect on estimates of the death toll.[166]

Other figures have been given which differ from what is indicated by reliable historical evidence. Numbers as high as 3 million appear in reports requested immediately after the war by the Central Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes in Poland.[168] During the Sobibor trials in the 1960s, the judges adopted a figure of 152,000 victims, though they stressed that this was not a complete estimate but rather a minimum limited by the procedural rules concerning evidence.[169] Survivors have suggested numbers of victims significantly higher than what historians accept. Many recall a camp rumour that Heinrich Himmler's visit in February 1943 was intended to celebrate the millionth victim,[170] and others suggest figures even higher. Historian Marek Bem suggests that survivors' estimates disagree with the record because they reflect "the state of their emotions back then, as well as the drama and the scale of tragedy which happened in Sobibor".[171] Another high figure comes from one of the perpetrators, SS-Oberscharfuhrer Erich Bauer, who recalled his colleagues expressing regret that Sobibor "came last" in the competition among the Operation Reinhard camps, having claimed only 350,000 lives.[172]

Uprising

On the afternoon of 14 October 1943, members of the Sobibor underground covertly killed most of the on-duty SS officers and then led roughly 300 prisoners to freedom. This revolt was one of three uprisings by Jewish prisoners in extermination camps, the others being those at Treblinka extermination camp on 2 August 1943 and at Auschwitz-Birkenau on 7 October 1944.[173]

Lead up

In the summer of 1943, rumors began to circulate that Sobibor would soon cease operations. The prisoners understood that this would mean certain death for them all, since the final cohort of Bełżec prisoners had been gassed at Sobibor after dismantling their own camp. The Sobibor prisoners knew this since the Bełżec prisoners had sown messages into their clothing:[174]

We worked at Bełżec for one year and did not know where we would be sent next. They said it would be Germany… Now we are in Sobibór and know what to expect. Be aware that you will be killed also! Avenge us!”[174]

An escape committee formed in response to these rumors. Their leader was Leon Feldhendler, a former member of the judenrat in Żółkiewka. His job in the sorting barracks gave him access to additional food, sparing him from the hunger which robbed other workers of their mental acuity.[175] However, the escape committee made little progress that summer. In light of previous betrayals and the ever-looming threat of collective punishment, they kept their discussions limited to roughly seven Polish Jews. This insularity severely limited their capacity to form a plan, since none of their members had the military or strategic experience necessary to carry out a mass escape. By late September, their discussions had stalled.[175]

On September 22, the situation changed dramatically when twenty-some Jewish Red Army POWs arrived at Sobibor on a transport from the Minsk Ghetto and were selected for labor. Among them was Alexander Pechersky, a political commissar who would go on to lead the revolt. The members of the escape committee approached the newly arrived Russians with both excitement and caution. On one hand, the Russians had the expertise that would allow them to pull off an escape, but on the other hand, it wasn’t clear whether there was sufficient mutual trust.[176]

Feldhendler introduced himself to Pechersky using the alias “Baruch” and invited him to share news from outside the camp at a meeting in the women's barracks. Feldhendler was shocked to discover Pechersky's limited ability to speak Yiddish, the common language of Eastern European Jews. However, the two were able to communicate in Russian, and Pechersky agreed to attend. At the meeting, Pechersky gave a speech and took questions while his friend Solomon Leitman translated into Yiddish. (Leitman was a Polish Jew who had befriended Pechersky in the Minsk Ghetto.) Members of the escape committee were in particular struck by Pechersky’s response to a question about whether Soviet partisans would liberate the camp: “If we want anything to happen, it will be up to us.”[68]

Over the next few weeks, Pechersky met regularly with the escape committee. These meetings were held in the women’s barracks under the pretext of him having an affair with a woman known as "Luka". At first, Pechersky and Leitman discussed a plan to dig a tunnel from the carpenter’s workshop in Lager I, which was close to the perimeter fence. This idea was abandoned as too difficult. If the tunnel was too deep, it would hit the high water table and flood. Too shallow, and it would detonate one of the mines. Furthermore, it was agreed that the plan would need to give all of the prisoners a chance at escaping, and it was deemed impossible to get 600 people through a tunnel without being caught.[177]

The ultimate idea for the revolt came to Pechersky while he was assigned to the forest brigade, chopping wood near Lager III. While working, he heard the sound of a child in the gas chamber screaming "Mama! Mama!". Overcome with his feeling of powerlessness and reminded of his own daughter Elsa, he decided that the plan could not be a mere escape. Rather, it would have to be a revolt.[178]

The revolt

On 14 October 1943, Pechersky's escape plan began. Starting at 4pm, SS officers were lured to workshops on a variety of pretexts, such as being fitted for new boots or expensive clothes. They were then stabbed to death with carpenters' axes, awls and chisels discreetly recovered from property left by gassed Jews; with other tradesmen's sharp tools or with crude knives and axes made in the camp's machine shop. The blood was covered up with sawdust on the floor.[179] The escapees were armed with a number of hand grenades, a rifle, a submachine gun and several pistols that the prisoners stole from the German living quarters, as well as the sidearms captured from the dead SS men.[180] Shlomo Szmajzner also stole three rifles from the armory after convincing the watchman on guard that he was on a repair mission. He handed two rifles to Soviet POWs and insisted on keeping the third.[181][182][183] In the turmoil of the escape, Szmajzner shot a tower guard.[184][185]

Earlier in the day, SS-Oberscharführer Erich Bauer, at the top of the death list created by Pechersky, unexpectedly drove out to Chełm for supplies. The uprising was almost postponed since the prisoners believed that Bauer's death was necessary for the success of the escape. Bauer came back early from Chełm, discovered that SS-Scharführer Rudolf Beckmann had been assassinated and began shooting at the prisoners. The sound of the gunfire prompted Pechersky to jump on a table and announce the beginning of the open revolt. Philip Bialowitz recalled him saying, "If you survive, bear witness! Tell the world about this place!"[186]

Disorganized groups of prisoners ran in every direction. Ada Lichtman, a survivor of the escape recalled "Suddenly we heard shots... Mines started to explode. Riot and confusion prevailed, everything was thundering around. The doors of the workshop were opened, and everyone rushed through... We ran out of the workshop. All around were the bodies of the dead and wounded". Pechersky was able to escape into the woods and at the end of the uprising, eleven German SS personnel and an unknown number of Ukrainian guards had been killed.[187][188][189][190][191][188]

Aftermath

Immediately after the escape, in the forest, a group of fifty prisoners followed Pechersky. After a few days, Pechersky and seven other Russian POWs left claiming that they would return with food. However, they instead left to cross the Bug river and make contact with the partisans. After Pechersky did not return, the remaining prisoners split into smaller groups and sought separate ways.[192]

In 1980, Thomas Blatt asked Pechersky why he abandoned the other survivors. Pechersky answered,

My job was done. You were Polish Jews in your own terrain. I belonged in the Soviet Union and still considered myself a soldier. In my opinion, the chances for survival were better in smaller units. To tell the people straight forward: "we must part" would not have worked. You have seen, they followed every step of mine, we all would perish. [...] what can I say? You were there. We were only people. The basic instincts came into play. It was still a fight for survival. This is the first time I hear about money collection. It was a turmoil, it was difficult to control everything. I admit, I have seen the imbalance in the distribution of the weaponry but you must understand, they would rather die than to give up their arms.— Pechersky [193]

Dutch historian and Sobibor survivor Jules Schelvis estimates that 158 inmates perished in the Sobibor revolt, killed by the guards or in the minefield surrounding the camp. A further 107 were killed either by the SS, Wehrmacht, or Orpo police units pursuing the escapees. Some 53 insurgents died of other causes between the day of the revolt and 8 May 1945. There were 58 known survivors, 48 male and 10 female, from among the Arbeitshäftlinge prisoners performing slave-labour for the daily operation of Sobibor. Their time in the camp ranged from several weeks to almost two years.[194]

Liquidation and demolition

The day after the revolt, the SS shot all 159 prisoners still inside the camp.[196][197] Several days later, on 19 October, SS chief Heinrich Himmler ordered that the camp be closed and dismantled.[198][196] Jewish slave laborers were sent to Sobibor from Treblinka in order to perform the necessary labor.[199] These workers deconstructed most of the camp's buildings including the gas chambers, whose foundations were covered with asphalt and made to look like a road.[200] However, they left behind the watchmens' barracks, the forestry tower, and the kommandant's house. The commandant's house exists today as a private residence, but the forestry tower was demolished in 2004 after decaying nearly to the point of collapse.[40] The work was finished by the end of the month, and all of the Jews brought from Treblinka were shot between 1 November and 10 November.[201][1]

Post-war

Survivors

Several thousand deportees to Sobibor were spared the gas chambers because they were transferred to slave-labour camps in the Lublin reservation, upon arriving at Sobibor. These people spent several hours at Sobibor and were transferred almost immediately to slave-labour projects including Majdanek and the Lublin airfield camp, where materials looted from the gassed victims were prepared for shipment to Germany. Other forced labour camps included Krychów, Dorohucza, and Trawniki. Most of these prisoners were killed in the November 1943 massacre Operation Harvest Festival, or perished in other ways before the end of the war.[194] Of the 34,313 Jews deported to Sobibor from the Netherlands according to train schedules, 18 are known to have survived the war.[202] In June 2019 the last known survivor of the revolt, Semyon Rosenfeld, who was born in Ukraine, died at a retirement home near Tel Aviv, Israel, aged 96.[203]

Trials

SS-Oberscharführer Erich Bauer was the first SS officer tried for crimes at Sobibor.[204] Bauer was arrested in 1949 when two former Jewish prisoners from Sobibor, Samuel Lerer and Esther Terner, recognized him at a fairground in Kreuzberg.[205] A year later, Bauer was sentenced to death for crimes against humanity, though his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.[206] The second Sobibor trials occurred shortly after, against Hubert Gomerski who was given a life sentence and against Johann Klier who was acquitted.[204]

The third Sobibor trials were the Hagen Trials, whose defendants included Karl Frenzel and Kurt Bolender. Frenzel was sentenced to life imprisonment for personally killing 6 Jews and participating in the mass murder of an additional 150,000. Bolender committed suicide before sentencing.

A few of the watchmen who served at Sobibor were brought to trial in the Soviet Union, including B. Bielakow, M. Matwijenko, I. Nikifor, W. Podienko, F. Tichonowski, Emanuel Schultz, and J. Zajcew. They were convicted of treason and war crimes and were subsequently executed. In April 1963, at a court in Kiev where Alexander Pechersky was the chief prosecution witness, ten former watchmen were found guilty and executed. One was sentenced to 15 years in prison.[207] A third Soviet trial was held in Kiev in June 1965, where three watchmen Sobibor and Belzec were executed by a firing squad.[207]

In May 2011, John Demjanjuk was convicted for being an accessory to the murder of 28,060 Jews while serving as a watchman at Sobibor.[208] He was sentenced to five years in prison, but was released pending appeal. He died in a German nursing home on 17 March 2012, aged 91, while awaiting the hearing.[209]

The site post-war

In the first twenty years after the war, the site of the camp was practically deserted.[210] Locals visited the site to dig for valuables.[199][211] A visitor in the early 1950s reported "there is nothing left in Sobibor".[212]

The first monuments to Sobibor victims were erected on the site in 1965. Installed by the Council for the Protection of Struggle and Martyrdom Sites, these consisted of a memorial wall, an obelisk symbolizing the gas chambers, a sculpture of a mother and her child, and a mausoleum called the "Memory Mound".[212] The memorial wall originally listed Jews as just one of the groups persecuted at Sobibor, but the plaque was revised in 1993 to reflect the general historical consensus that only Jews were exterminated at Sobibor.[213]

The Włodawa Museum, which was responsible for the monument, established a separate Sobibór branch on 14 October 1993, on the 50th anniversary of the armed uprising of Jewish prisoners there.[214] Following the celebrations of the 60th anniversary of the revolt in 2003, the grounds of the former death camp received a grant largely funded by the Dutch government to improve the exhibits. New walkways were introduced with signs indicating points of interest, but close to the burial pits, bone fragments still litter the area.[215]

Historical and archaeological research

Until the 1990s, little was known about the physical site of the camp beyond what survivors and perpetrators could recall. After the revolt, the camp had been dismantled and planted over with trees, concealing evidence of what happened there. Archaeological investigations at Sobibor began in the 1990s.[202] In 2001, a team led by Andrzej Kola from Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń investigated the former area of Lager III, finding seven pits with a total volume of roughly 19,000 square meters. While some of these pits appear to have been mass graves, others may have been used for open air cremation.[216] The team also found pieces of barbed wire embedded in trees, which they identified as remnants of the camp's perimeter fence. Thus, they were able to partially map out the perimeter of the former camp site, which had not previously been known.[217]

In 2007, the duo of Wojciech Mazurek and Yoram Haimi began to conduct small-scale investigations. Since 2013, the camp has been excavated by a joint team of Polish, Israeli, Slovak, and Dutch archeologists led by Mazurek, Haimi, and Ivar Schute. In accordance with Jewish law, these excavations avoided mass graves and were supervised by Polish rabbis. Their discovery of the foundations of the gas chambers, in 2014, attracted worldwide media attention. Between 2011 and 2015, thousands of personal items belonging to victims were uncovered by the teams. At the ramp, large dumps of household items, including "glasses, combs, cutlery, plates, watches, coins, razors, thimbles, scissors, toothpaste" were found, but few valuables; Schute suggests that these items are indicative of victims' hopes to survive as forced laborers. In Camp 3, the area around the gas chambers, household items were not found but "gold fillings, dentures, pendants, earrings, and a gold ring" were. Schute notes that such objects could have been concealed by naked individuals, and argues that it is evidence for the "processing" of bodies at this location.[202]

In 2020, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum acquired a collection of photographs and documents from the descendants of Johann Niemann. These photos show daily life amongst the camp staff. Many show the perpetrators drinking, playing music, and playing chess with one another. These photos are significant because there had previously only been two known photographs of Sobibor during its operation. These materials have been published in a German language book and ebook by Metropol Verlag entitled Fotos aus Sobibor. The photos received voluminous press coverage because two of them appear to show John Demjanjuk in the camp.[218][219][220]

Dramatisations and testimonies

The mechanics of Sobibor death camp were the subject of interviews filmed on location for the 1985 documentary film Shoah by Claude Lanzmann. In 2001, Lanzmann combined unused interviews with survivor Yehuda Lerner shot during the making of Shoah, along with new footage of Lerner, to tell the story of the revolt and escape in his followup documentary Sobibor, October 14, 1943, 4 p.m.[221]

In the 1978 American TV miniseries Holocaust broadcast in four parts, one of the principal characters, Rudi Weiss, a German Jew, is captured by the Nazis during a partisan attack upon a German convoy. Knocked unconscious, he wakes up in Sobibor, where he meets the Russian prisoners of war. The prisoners are initially suspicious of him as a possible German spy planted within their midst, but he wins their trust and becomes part of the group that kills German SS officers as part of the uprising. Weiss and his new POW comrades successfully escape Sobibor during the mass break-out. The revolt was dramatised in the 1987 British TV film Escape from Sobibor, directed by Jack Gold and in the 2018 Russian movie Sobibor, directed by Konstantin Khabensky.

One of the survivors, Regina Zielinski, has recorded her memories of the camp, and the escape in a conversation with Phillip Adams together with Elliot Perlman, in 2013 broadcast of Late Night Live by ABC.[222]

Notes

- Arad 1987, pp. 373–374.

- Leni Yahil, Ina Friedman, Ḥayah Galai, The Holocaust: the fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945 Oxford University Press US, 1991, pp.160, 161, 204; ISBN 0-19-504523-8.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 10.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 13.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 13–14.

- Cüppers et al. 2020, p. 152.

- Bem 2015, p. 46.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 23.

- Bem 2015, pp. 48–50.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 26–27.

- Bem 2015, p. 49–50.

- Bem 2015, p. 54.

- Bem 2015, p. 56.

- Arad 1987, pp. 30–31.

- Schelvis 2014, pp. 100–101.

- Arad 1987, p. 184.

- Chris Webb, Carmelo Lisciotto, Victor Smart (2009). "Sobibor Death Camp". HolocaustResearchProject.org. Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Bem 2015, p. 57.

- Schelvis 2014, p. 262.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 69,76.

- Cüppers et al. 2020, p. 136.

- Bem 2015, p. 70.

- Bem 2015, p. 71,73.

- Bem 2015, p. 73.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 77.

- Cüppers et al. 2020, p. 136,143.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 38.

- Webb 2017, p. 37.

- Webb 2017, pp. 313–314.

- Cüppers et al. 2020, p. 136,138.

- Bem 2015, pp. 67-68.

- Cüppers et al. 2020, pp. 134-135.

- Bem 2015, pp. 52,65,73.

- Bem 2015, p. 211.

- Cüppers et al. 2020, p. 130.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 29,37.

- Cüppers et al. 2020, p. 139.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 34,66.

- Bem 2007, p. 192.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 29.

- Webb 2017, p. 40.

- Bem 2015, p. 74.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 147.

- Cüppers et al. 2020, p. 140.

- Bem 2015, p. 7.

- Rashke 2013, p. 34.

- Arad 1987, pp. 257–258.

- Bem 2015, p. 72.

- Arad 1987, p. 249.

- Rashke 2013, pp. 96–98.

- Bem 2015, pp. 188–119.

- Bem 2015, p. 69.

- Rashke 2013, p. 168.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 88.

- Bem 2015, p. 186.

- Bem 2015, p. 212.

- Bem 2015, pp. 189–90,192,356.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 11.

- Arad 1987, p. 274.

- Bem 2015, p. 245.

- Bem 2015, p. 201.

- Rashke 2013, p. 159.

- Rashke 2013, p. 433.

- Bem 2015, p. 188.

- Rashke 2013, p. 162.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 150.

- Rashke 2013, p. 163.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 150–151.

- Bem 2015, p. 187.

- Bem 2015, pp. 199–201.

- Arad 1987, pp. 278.

- Bem 2015, pp. 186–188.

- Arad 1987, p. 277.

- Arad 1987, pp. 275–279.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 91.

- Bem 2015, pp. 196–197.

- Bem 2015, pp. 197–198.

- Bem 2015, pp. 198–199.

- Bem 2015, p. 237.

- Arad 1987, p. 272.

- Bem 2015, p. 68.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 87.

- Bem 2015, p. 238.

- Rashke 2013, p. 243.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 86.

- Bem 2015, p. 183.

- Arad 1987, p. 271.

- Bem 2015, pp. 183–184.

- Arad 1987, p. 252.

- Rashke 2013, p. 161.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 84.

- Bem 2015, pp. 188–189.

- Arad 1987, p. 251.

- Arad 1987, p. 269.

- Arad 1987, p. 153.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 83–84.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 89.

- Bem 2015, p. 194.

- Bem 2015, pp. 195–196.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 92.

- Bem 2015, p. 195.

- Rashke 2013, p. 188.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 83.

- Bem 2015, p. 200.

- Rashke 2013, pp. 161–162.

- Rashke 2013, pp. 273–274.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 69.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 252–253.

- Sereny 1974, pp. 252–253.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 33–36.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 245.

- Arad 1987, pp. 141–143,117–118.

- Webb 2017, p. 314.

- Sereny 1974, p. 131.

- Bem 2015, pp. 114–115.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 260.

- Bem 2015, p. 48.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 259.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 264.

- Bem 2015, p. 115.

- Bem 2015, p. 372.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 112,255.

- Bem 2015, p. 308.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 263–264.

- Bem 2015, pp. 112–113.

- Bem 2015, p. 116.

- Bem 2015, p. 110.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 245–246.

- Bem 2015, pp. 199–200.

- Rashke 2013, p. 144.

- Arad 1987, pp. 152–153.

- Cüppers et al. 2020, p. 175.

- Bem 2015, p. 111.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 84–85,245.

- Bem 2015, p. 122.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 34.

- Bem 2015, pp. 120–121.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 103.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 63,66.

- Cüppers et al. 2020, p. 191.

- Bem 2015, p. 123.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 35.

- Bem 2015, p. 130.

- Bem 2015, p. 124.

- Bem 2015, pp. 255–256.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 136–137.

- Bem 2015, p. 125.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 181.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 249–250.

- Bem 2015, p. 220.

- Schelvis 2014, pp. 71–72.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 100: Testimony of SS-Scharführer Erich Fuchs about his own installation of the (at least) 200 HP, V-shaped, 8 cylinder, water-cooled petrol engine at Sobibor.

- Arad 1987, p. 76.

- "Sobibor". The Holocaust Explained. Jewish Cultural Centre, London. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015 – via Internet Archive.

As part of the concealment of the camp's purpose, some Dutch Jews dislodging at the ramp were ordered to write "calming letters" to their relatives in the Netherlands, with made-up details about the welcome and living conditions. Immediately after that, they were taken to the gas chambers.

CS1 maint: unfit url (link) - "Michel Velleman (Sobibór, 2 juli 1943)". Digitaal Monument Joodse Gemeenschap in Nederland. Joods Monument. 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- Matt Lebovic "70 years after revolt, Sobibor secrets are yet to be unearthed", Times of Israel 14 October 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- Eberhardt 2015, p. 124.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 198.

- Bem 2015, p. 161.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 197.

- Bem 2015, pp. 219–275.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 197–198.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 199.

- Bem 2015, p. 165.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 224.

- Bem 2015, p. 178.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 4.

- Bem 2015, pp. 162–164.

- Bem 2015, pp. 165–166.

- Bem 2015, p. 117.

- Bem 2015, p. 182.

- Klee et al. 1991, p. 232.

- Arad 1987, pp. 219–275.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 144–145.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 147–148.

- Schelvis 2007, pp. 149–150.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 152.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 153.

- Erenburg, Grossman. Black Book: Uprising in Sobibor (in Russian) Retrieved on 2009-04-21

- Eichmann Trial: Testimony of Ya'akov Biskowitz Archived 2018-09-18 at the Wayback Machine, Session 65/3. Retrieved on 2009-05-08

- Jules Schelvis & Dunya Breur. "Stanislaw Szmajzner". sobiborinterviews.nl. NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

- Schelvis, Jules (2007). Sobibor: A history of a nazi death camp. Berg (Bloomsbury). p. 159f.

- Blatt, Thomas Toivi (1997). From the Ashes of Sobibor: A Story of Survival. Northwestern University Press. p. 150.

- Blatt, Thomas Toivi (1997). From the Ashes of Sobibor: A Story of Survival. Northwestern University Press. p. 153.

- Szmajzner, Stanislaw (1968). Inferno em Sobibor: A tragédia de um adolescente judeu. Bloch Editores – via Holocaust Research Project, extracts translated to English.

- Daniels, Jonny (8 August 2016). "Holocaust hero passes away at 90". Israel National News. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- Sobibor Murderers Article Archived 2008-05-04 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2010-09-05

- Yad Vashem: Escape under Fire: The Sobibor Uprising Retrieved on 2009-05-08

- The Sobibor Death Camp Retrieved on 2010-09-06

- Sobibor survivor: 'I polished SS boots as dying people screamed Retrieved on 2010-09-06

- Ukrainians guards took part in extermination Retrieved on 2010-09-06

- Jules Schelvis (2003). Vernichtungslager Sobibor. UNRAST-Verlag, Hamburg/Münster. p. 212ff.

- Toivi Blatt interviews Sasha Pechersky about Luka in 1980 Retrieved on 2009-05-08

- Schelvis, Jules (2004). Vernietigingskamp Sobibor. De Bataafsche Leeuw. ISBN 9789067076296. Uitgeverij Van Soeren & Co (booksellers).

- Cüppers et al. 2020, p. 137.

- Rashke 2013, p. 4.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 188.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 168.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 191.

- Reuters, Archaeologists Uncover Buried Gas Chambers At Sobibor Death Camp. The Huffington Post, 18 September 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 190.

- Schute 2018, The Case of Sobibor: A German Extermination Camp in Eastern Poland.

- "Last survivor of Sobibor death camp uprising dies". BBC News. 4 June 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- Schelvis 2007, p. 2.

- Dick de Mildt. In the Name of the People: Perpetrators of Genocide, p. 381-383. Brill, 1996.

- Klee, Ernst, Dressen, Willi, Riess, Volker The Good Old Days: The Holocaust as Seen by Its Perpetrators and Bystanders. ISBN 1-56852-133-2.

- Arad, Yitzhak (2018). "Appendix B: The Fate of the Perpetrators of Operation Reinhard". The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, Revised and Expanded Edition: Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. Indiana University Press. pp. 399–400. ISBN 978-0-253-03447-2.

- Douglas 2016, p. 2,252.

- Douglas 2016, pp. 253, 257.

- Bem 2015, p. 340.

- Bem 2015, pp. 292–293.

- Bem 2015, p. 340-342.

- Rashke 2013, pp. 493,512.

- Bem 2015, p. 11,337,353.

- Lest we forget (14 March 2004), "Extermination camp Sobibor". Archived from the original on 7 March 2005. Retrieved 7 March 2005.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) The Holocaust. Retrieved on 17 May 2013.

- Bem 2015, pp. 220–221.

- Bem 2015, pp. 106–107.

- Sopke, Kerstin; Moulson, Geir (28 January 2020). "Berlin museum unveils photos possibly featuring Demjanjuk at Sobibor death camp". Times of Israel. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Lebovic, Matt (3 February 2020). "Sobibor photo album remaps Nazi death camp famous for 1943 prisoner revolt". Times of Israel. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Cüppers et al. 2020.

- Weissman 2020, p. 139.

- Regina Zielinski with Phillip Adams 'Escape from the Sobibor WW2 death camp,' Late Night Live Interview 29 October 2013

References

- Arad, Yitzhak (1987). Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253213053.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bem, Marek (2015). Sobibor Extermination Camp 1942-1943 (PDF). Translated by Karpiński, Tomasz; Sarzyńska-Wójtowicz, Natalia. Stichting Sobibor. ISBN 978-83-937927-2-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blatt, Thomas (1997). From the Ashes of Sobibor. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0810113023.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chmielewski, Jakub (2014). Obóz zagłady w Sobiborze [Death camp in Sobibor] (in Polish). Lublin: Ośrodek Brama Grodzka. Retrieved 25 September 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cüppers, Martin; Gerhardt, Annett; Graf, Karin; Hänschen, Steffen; Kahrs, Andreas; Lepper, Anne; Ross, Florian (2020). Fotos aus Sobibor (in German). Metropol Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86331-506-1.

- Douglas, Lawrence (2016). The Right Wrong Man: John Demjanjuk and the Last Great Nazi War Crimes Trial. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-7315-9.

- Eberhardt, Piotr (2015). "Estimated Numbers of Victims of the Nazi Extermination Camps". Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth Century Eastern Europe. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317470960.

- Gilead, Isaac; Haimi, Yoram; Mazurek, Wojciech (2010). "Excavating Nazi Extermination Centres". Present Pasts. 1. doi:10.5334/pp.12.

- Gross, Jan Tomasz (2012). Golden Harvest: Events at the Periphery of the Holocaust. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199939312.

- Klee, Ernst; Dressen, Willi; Riess, Volker (1991). "The Good Old Days": The Holocaust as Seen by Its Perpetrators and Bystanders. Konecky Konecky. ISBN 978-1-56852-133-6.

- Rashke, Richard (2013) [1982]. Escape from Sobibor. Open Road Integrated Media, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-4804-5851-2.

- Schelvis, Jules (2007). Sobibor: A History of a Nazi Death Camp. Berg, Oxford & New Cork. ISBN 978-1-84520-419-8.

- Schelvis, Jules (2014) [2007]. Sobibor: A History of a Nazi Death Camp. Translated by Dixon, Karin. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1472589064.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schute, Ivar (2018). "Collecting Artifacts on Holocaust Sites: A Critical review of Archaeological Research in Ybenheer, Westerbork, and Sobibor". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 22 (3): 593–613. doi:10.1007/s10761-017-0437-y.

- Sereny, Gitta (1974). Into That Darkness: from Mercy Killing to Mass Murder. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-056290-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sobibor Museum (2014) [2006], Historia obozu [Camp history], Dr. Krzysztof Skwirowski, Majdanek State Museum, Branch in Sobibór (Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku, Oddział: Muzeum Byłego Obozu Zagłady w Sobiborze), archived from the original on 7 May 2013, retrieved 25 September 2014

- Webb, Chris (2017). Sobibor Death Camp: History, Biographies, Remembrance. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-3-8382-6966-5.

- Weissman, Gary (2020). "Yehuda Lerner's Living Words Translation and Transcription in Sobibór, October 14, 1943, 4. p.m.". In McGlothlin, Erin; Prager, Brad (eds.). The Construction of Testimony: Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah and Its Outtakes. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-4735-5.

Further reading

- Arad, Yitzhak (2018) [1987]. The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, Revised and Expanded Edition: Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-02530-2.

- Berger, Sara (2013). Experten der Vernichtung: Das T4-Reinhardt-Netzwerk in den Lagern Belzec, Sobibor und Treblinka (in German). Hamburger Edition HIS. ISBN 978-3-86854-607-1.

- Novitch, Miriam (1980). Sobibor, Martyrdom and Revolt: Documents and Testimonies. ISBN 0-89604-016-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sobibór extermination camp. |

- Sobibor on the Yad Vashem website

- SOBIBOR at United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- The Sobibor Death Camp at HolocaustResearchProject.org

- Sobibor Archaeological Project at Israel Hayom

- Archaeological Excavations at Sobibór Extermination Site

- Survivor Thomas Blatt, 18-minute audio interview by WMRA

- International archeological research in the area of the former German-Nazi extermination camp in Sobibór.

- Onderzoek – Vernietigingskamp Sobibor (records of testimonies, transportation lists and other documents, from the archives of the NIOD Instituut voor Oorlogs-, Holocaust- en Genocidestudies, Netherlands)

- Archaeological Excavations at Sobibór Extermination Site, at Yad Vashem website