Rudolf Höss

Rudolf Franz Ferdinand Höss (also Höß, Hoeß or Hoess; 25 November 1901 – 16 April 1947)[2][3] was a German Schutzstaffel (SS) functionary during the Nazi era who was later convicted as a war criminal. He was the longest-serving commandant of Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp. He tested and implemented means to accelerate Hitler's plan to systematically exterminate the Jewish population of Nazi-occupied Europe, known as the Final Solution. On the initiative of one of his subordinates, Karl Fritzsch, Höss introduced the pesticide Zyklon B, containing hydrogen cyanide, used in the gas chambers.[4][5]

Rudolf Höss | |

|---|---|

Höss at trial before the Polish Supreme National Tribunal, 1947 | |

| Born | Rudolf Franz Ferdinand Höß 25 November 1901 |

| Died | 16 April 1947 (aged 45) |

| Known for | Commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp 4 May 1940 – 1 December 1943 8 May 1944 – 18 January 1945 |

| Spouse(s) | Hedwig Hensel ( m. 1929) |

| Children | 5 |

| Criminal charge | Nazi crimes against the Polish nation |

| Trial | Supreme National Tribunal |

| Penalty | Death penalty |

| SS career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Death's Head Units |

| Years of service | 1934–1945 |

| Rank | SS-Obersturmbannführer |

Höss joined the Nazi Party in 1922 at the age of 21 and the SS in 1934. From 4 May 1940 to November 1943, and again from 8 May 1944 to 18 January 1945, he was in charge of Auschwitz, where more than a million people were killed before the defeat of Nazi Germany.[6] Höss was hanged in 1947 following a trial before the Polish Supreme National Tribunal. During his imprisonment, at the request of the Polish authorities, he wrote his memoirs, released in English under the title Commandant of Auschwitz: The Autobiography of Rudolf Hoess.[7]

Family

Höss was born in Baden-Baden into a strict Catholic family.[8] He lived with his mother Lina (née Speck) and father Franz Xaver Höss. Höss was the eldest of three children and the only son. He was baptized Rudolf Franz Ferdinand on 11 December 1901. He was a lonely child with no companions of his own age until he entered elementary school; all of his associations were with adults. He claimed in his autobiography that he was briefly abducted by gypsies in his youth.[9] His father, a former army officer who served in German East Africa, ran a tea and coffee business; he brought his son up on strict religious principles and with military discipline, having decided that he would enter the priesthood. Höss grew up with an almost fanatical belief in the central role of duty in a moral life. During his early years, there was a constant emphasis on sin, guilt, and the need to do penance.

Rudolf Höss;

married on 17 August 1929 to Hedwig Hensel[10]

- Klaus Höss: born 6 February 1930 and died in Australia

- Heidetraud Höss: born 9 April 1932.

- Inge-Brigitt Höss: born 18 August 1933.

- Hans-Jürgen Höss: born in May 1937

- Rainer Höss: born 25 May 1965 in Stuttgart.

- Annegret Höss: born 7 November 1943.

Youth and World War I

When World War One broke out, Höss served briefly in a military hospital and then, at age 14, was admitted to his father's and grandfather's old regiment, the German Army's 21st Regiment of Dragoons. Aged 15, he fought with the Ottoman Sixth Army at Baghdad, at Kut-el-Amara, and in Palestine.[11] While stationed in Turkey, he rose to the rank of Feldwebel (sergeant-in-chief) and at 17 was the youngest non-commissioned officer in the army. Wounded three times and a victim of malaria, he was awarded the Gallipoli Star, the Iron Cross first and second class and other decorations.[12] Höss also briefly commanded a cavalry unit. When the news of the armistice reached Damascus, where he was at that time, he and a few others decided not to wait for the British to arrest them as prisoners of war, but instead to try to ride all the way back home. This involved traversing the enemy territory of Romania, but they eventually made it back home to Bavaria.[13]

Joining the Nazi party

After the Armistice of 11 November 1918, Höss completed his secondary education and soon joined some of the emerging nationalist paramilitary groups, first the East Prussian Volunteer Corps, and then the Freikorps "Rossbach" in the Baltic area, Silesia and the Ruhr. Höss participated in the armed terror attacks on Polish people during the Silesian uprisings against the Germans, and on French nationals during the Occupation of the Ruhr. He joined the Nazi Party in 1922 (Member No. 3240) after hearing a speech by Adolf Hitler in Munich.

On 31 May 1923, in Mecklenburg, Höss and members of the Freikorps attacked and beat to death local schoolteacher Walther Kadow on the wishes of farm supervisor Martin Bormann, who later became Hitler's private secretary.[14] Kadow was believed to have tipped off the French occupational authorities that Höss' fellow Nazi, paramilitary soldier Albert Leo Schlageter, was carrying out sabotage operations against French supply lines. Schlageter was arrested and executed on 26 May 1923; soon afterwards Höss and several accomplices, including Bormann, took their revenge on Kadow.[14] In 1923, after one of the killers confessed to a local newspaper, Höss was arrested and tried as the ringleader. Although he later claimed that another man was actually in charge, Höss accepted the blame as the group's leader. He was convicted and sentenced (on 15[15] or 17 May 1924[16]) to ten years in Brandenburg penitentiary, while Bormann received a one-year sentence.[17]

Höss was released in July 1928 as part of a general amnesty and joined the Artaman League, an anti-urbanization movement, or back-to-the-land movement, that promoted a farm-based lifestyle. On 17 August 1929, he married Hedwig Hensel (3 March 1908 – 1989), whom he met in the Artaman League. Between 1930 and 1943 they had five children: two sons (Klaus and Hans-Rudolf) and three daughters (Ingebrigitt, Heidetraut and Annegret). Ingebrigitt was born on a farm in northern Germany in 1934 after Heidetraut, Höss's eldest daughter, was born in 1932; and Annegret, the youngest, was born in Auschwitz in November 1943.[18][19] It was during this time that he became acquainted with Heinrich Himmler.[20]

SS career

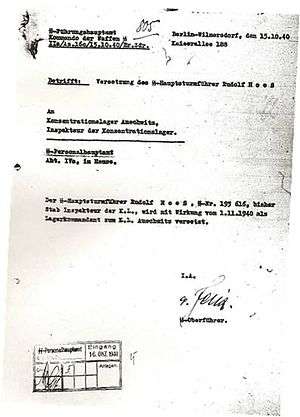

Höss joined the SS on 1 April 1934, on Himmler's effective call-to-action,[21] and joined the SS-Totenkopfverbände (Death's Head Units) in the same year. He came to admire Himmler so much that he considered whatever he said to be the "gospel" and preferred to display his picture in his office rather than that of Hitler. Höss was assigned to the Dachau concentration camp in December 1934, where he held the post of Blockführer. His mentor at Dachau was Obergruppenführer Theodor Eicke. In 1938, Höss was promoted to SS-Hauptsturmführer (captain) and was made adjutant to Hermann Baranowski in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. He joined the Waffen-SS in 1939 after the invasion of Poland. Höss excelled in that capacity, and was recommended by his superiors for further responsibility and promotion. By the end of his tour of duty there, he was serving as administrator of prisoners' property.[22][23]

Auschwitz command

On 1 May 1940, Höss was appointed commandant of a prison camp in western Poland, a territory Germany had incorporated into the province of Upper Silesia. The camp was built around an old Austro-Hungarian (and later Polish) army barracks near the town of Oświęcim; its German name was Auschwitz.[24] Höss commanded the camp for three and a half years, during which he expanded the original facility into a sprawling complex known as Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Höss had been ordered "to create a transition camp for ten thousand prisoners from the existing complex of well-preserved buildings," and he went to Auschwitz determined "to do things differently" and develop a more efficient camp than those at Dachau and Sachsenhausen where he had previously served.[25] Höss lived at Auschwitz in a villa with his wife and five children.[26]

The earliest inmates at Auschwitz were Soviet prisoners-of-war and Polish prisoners, including peasants and intellectuals. Some 700 arrived in June 1940, and were told they would not survive more than three months.[27] At its peak, Auschwitz comprised three separate facilities: Auschwitz I, Auschwitz II-Birkenau and Auschwitz III-Monowitz. These included many satellite sub-camps, and the entire camp was built on about 8,000 hectares (20,000 acres) that had been cleared of all inhabitants.[22] Auschwitz I was the administrative centre for the complex; Auschwitz II Birkenau was the extermination camp where most of the murders were committed; and Auschwitz III Monowitz was the slave-labour camp for I.G. Farbenindustrie AG, and later other German industries. The main purpose of Monowitz was the production of buna, a form of synthetic rubber.

Mass murder

In June 1941, according to Höss's trial testimony, he was summoned to Berlin for a meeting with Himmler "to receive personal orders".[22] Himmler told Höss that Hitler had given the order for the "Final solution". According to Höss, Himmler had selected Auschwitz for the extermination of Europe's Jews "on account of its easy access by rail and also because the extensive site offered space for measures ensuring isolation". Himmler described the project as a "secret Reich matter" and told Höss not to speak about it with SS-Gruppenführer Richard Glücks, head of the Nazi camp system run by the Death's Head Unit.[22] Höss said that "no one was allowed to speak about these matters with any person and that everyone promised upon his life to keep the utmost secrecy". He told his wife about the camp's purpose only at the end of 1942, since she already knew about it from Fritz Bracht. Himmler told Höss that he would be receiving all operational orders from Adolf Eichmann, who arrived at the camp four weeks later.[22]

Höss began testing and perfecting techniques of mass murder on 3 September 1941.[28] His experiments led to Auschwitz becoming the most efficiently murderous instrument of the Final Solution and the Holocaust's most potent symbol.[29] According to Höss, during standard camp operations, two or three trains carrying 2,000 prisoners each would arrive daily for four to six weeks. The prisoners were unloaded in the Birkenau camp; those fit for labour were marched to barracks in either Birkenau or one of the Auschwitz camps, while those unsuitable for work were driven into the gas chambers. At first, small gassing bunkers were located deep in the woods to avoid detection. Later, four large gas chambers and crematoria were constructed in Birkenau to make the killing process more efficient, and to handle the increasing rate of extermination.[22]

Technically [it] wasn't so hard—it would not have been hard to exterminate even greater numbers.... The killing itself took the least time. You could dispose of 2,000 head in half an hour, but it was the burning that took all the time. The killing was easy; you didn't even need guards to drive them into the chambers; they just went in expecting to take showers and, instead of water, we turned on poison gas. The whole thing went very quickly.[30]

Höss experimented with various gassing methods. According to Eichmann's trial testimony in 1961, Höss told him that he used cotton filters soaked in sulfuric acid for early killings. Höss later introduced hydrogen cyanide (prussic acid), produced from the pesticide Zyklon B, to the process of extermination, after his deputy Karl Fritzsch had tested it on a group of Russian prisoners in 1941.[5][4] With Zyklon B, he said that it took 3–15 minutes for the victims to die and that "we knew when the people were dead because they stopped screaming."[31]

In 1942, Höss had an affair with an Auschwitz inmate, a political prisoner named Eleonore Hodys[32] (or Nora Mattaliano-Hodys).[33] The woman became pregnant, and was imprisoned in a standing-only arrest cell. Released from the arrest, she had an abortion in a camp hospital in 1943 and, according to her later testimony,[34] just barely evaded being selected to be killed. The affair may have led to Höss's recall from the Auschwitz command in 1943.[33] SS judge Georg Konrad Morgen and his assistant Wiebeck investigated the case in 1944, interviewed Hodys and Höss and intended to proceed against Höss, but the case was dismissed. Morgen, Wiebeck and Hodys gave testimony after the war.[32][33]

After being replaced as the Auschwitz commander by Arthur Liebehenschel, on 10 November 1943, Höss assumed Liebehenschel's former position as the head of Amt D I in Amtsgruppe D of the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office (WVHA); he also was appointed deputy of the inspector of the concentration camps under Richard Glücks.

Operation Höss

On 8 May 1944, Höss returned to Auschwitz to supervise Operation Höss, in which 430,000 Hungarian Jews were transported to the camp and killed in 56 days[35] between May and July. Even Höss' expanded facility could not handle the huge number of victims' corpses, and the camp staff were obliged to dispose of thousands of bodies by burning them in open pits.[36]

Arrest, trial, and execution

In the last days of the war, Himmler advised Höss to disguise himself among Kriegsmarine personnel. He evaded arrest for nearly a year. When arrested on 11 March 1946 in Gottrupel (Germany), he was disguised as a gardener and called himself Franz Lang.[37] His wife had revealed his whereabouts to protect her son, Klaus, who was being “badly beaten” by British soldiers.[38][39] The British force that captured Höss included Hanns Alexander, a British captain originally from Berlin who was forced to flee to England with his entire family during the rise of Nazi Germany.[40] According to Alexander, Höss attempted to bite into a cyanide pill once he was discovered.[41] Höss initially denied his identity "insisting he was a lowly gardener, but Alexander saw his wedding ring and ordered Höss to take it off, threatening to cut off his finger if he did not. Höss' name was inscribed inside. The soldiers accompanying Alexander began to beat Höss with axe handles. After a few moments and a minor internal debate, Alexander pulled them off."[37][42]

Rudolf Höss testified at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg on 15 April 1946, where he gave a detailed accounting of his crimes. He was called as a defense witness by Ernst Kaltenbrunner's lawyer, Dr. Kauffman.[43][44] The transcript of Höss' testimony was later entered as evidence during the 4th Nuremberg Military Tribunal known as the Pohl Trial, named for principal defendant SS-Obergruppenführer Oswald Pohl.[45] Affidavits that Rudolf Höss made while imprisoned in Nuremberg were also used at the Pohl and IG Farben trials.

In his affidavit made at Nuremberg on 5 April 1946, Höss stated:

I commanded Auschwitz until 1 December 1943, and estimate that at least 2,500,000 victims were executed and exterminated there by gassing and burning, and at least another half million succumbed to starvation and disease, making a total of about 3,000,000 dead. This figure represents about 70% or 80% of all persons sent to Auschwitz as prisoners, the remainder having been selected and used for slave labor in the concentration camp industries. Included among the executed and burnt were approximately 20,000 Russian prisoners of war (previously screened out of Prisoner of War cages by the Gestapo) who were delivered at Auschwitz in Wehrmacht transports operated by regular Wehrmacht officers and men. The remainder of the total number of victims included about 100,000 German Jews, and great numbers of citizens (mostly Jewish) from The Netherlands, France, Belgium, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Greece, or other countries. We executed about 400,000 Hungarian Jews alone at Auschwitz in the summer of 1944.[46]

When accused of murdering three and a half million people, Höss replied, "No. Only two and one half million—the rest died from disease and starvation."[47]

On 25 May 1946, he was handed over to Polish authorities and the Supreme National Tribunal in Poland tried him for murder. In his essay on the Final Solution in Auschwitz, which he wrote in Kraków, he revised the previously given death toll:[48]

I myself never knew the total number, and I have nothing to help me arrive at an estimate.

I can only remember the figures involved in the larger actions, which were repeated to me by Eichmann or his deputies.

From Upper Silesia and the General Gouvernement 250,000

Germany and Theresienstadt 100,000

Holland 95,000

Belgium 20,000

France 110,000

Greece 65,000

Hungary 400,000

Slovakia 90,000 [Total 1,130,000]

I can no longer remember the figures for the smaller actions, but they were insignificant by comparison with the numbers given above. I regard a total of 2.5 million as far too high. Even Auschwitz had limits to its destructive capabilities.

In his memoir, he also revealed his mistreatment at the hands of his British captors:[49]

During the first interrogation they beat me to obtain evidence. I do not know what was in the transcript, or what I said, even though I signed it, because they gave me liquor and beat me with a whip. It was too much even for me to bear. The whip was my own. By chance it had found its way into my wife's luggage. My horse had hardly ever been touched by it, much less the prisoners. Somehow one of the interrogators probably thought that I had used it to constantly whip the prisoners.

After a few days I was taken to Minden on the Weser River, which was the main interrogation center in the British zone. There they treated me even more roughly, especially the first British prosecutor, who was a major. The conditions in the jail reflected the attitude of the first prosecutor. [...]

Compared to where I had been before, Imprisonment with the IMT [International Military Tribunal] was like staying in a health spa.

His trial lasted from 11 to 29 March 1947. Höss was sentenced to death by hanging on 2 April 1947. The sentence was carried out on 16 April next to the crematorium of the former Auschwitz I concentration camp. He was hanged on a short-drop gallows constructed specifically for that purpose, at the location of the camp's Gestapo. The message on the board that marks the site reads:

This is where the camp Gestapo was located. Prisoners suspected of involvement in the camp's underground resistance movement or of preparing to escape were interrogated here. Many prisoners died as a result of being beaten or tortured. The first commandant of Auschwitz, SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Höss, who was tried and sentenced to death after the war by the Polish Supreme National Tribunal, was hanged here on 16 April 1947.

Höss wrote his autobiography while awaiting execution; it was published in 1956 as Kommandant in Auschwitz; autobiographische Aufzeichnungen and later as Death Dealer: the Memoirs of the SS Kommandant at Auschwitz (among other editions). It consisted of two parts, one about his own life and the second about other SS men with whom he had become acquainted, mainly Heinrich Himmler and Theodor Eicke, but several others as well.[50][51]

After discussions with Höss during the Nuremberg trials at which he testified, the American military psychologist Gustave Gilbert wrote the following:

In all of the discussions, Höss is quite matter-of-fact and apathetic, shows some belated interest in the enormity of his crime, but gives the impression that it never would have occurred to him if somebody hadn't asked him. There is too much apathy to leave any suggestion of remorse and even the prospect of hanging does not unduly stress him. One gets the general impression of a man who is intellectually normal, but with the schizoid apathy, insensitivity and lack of empathy that could hardly be more extreme in a frank psychotic.[52]

Four days before he was executed, Höss acknowledged the enormity of his crimes in a message to the state prosecutor:

My conscience compels me to make the following declaration. In the solitude of my prison cell, I have come to the bitter recognition that I have sinned gravely against humanity. As Commandant of Auschwitz, I was responsible for carrying out part of the cruel plans of the 'Third Reich' for human destruction. In so doing I have inflicted terrible wounds on humanity. I caused unspeakable suffering for the Polish people in particular. I am to pay for this with my life. May the Lord God forgive one day what I have done. I ask the Polish people for forgiveness. In Polish prisons I experienced for the first time what human kindness is. Despite all that has happened I have experienced humane treatment which I could never have expected, and which has deeply shamed me. May the facts which are now coming out about the horrible crimes against humanity make the repetition of such cruel acts impossible for all time.[25]

Shortly before his execution, Höss returned to the Catholic Church. On 10 April 1947, he received the sacrament of penance from Fr. Władysław Lohn, S.J., provincial of the Polish Province of the Society of Jesus. On the next day, the same priest administered to him Holy Communion as Viaticum.[53]

In a farewell letter to his wife, Höss wrote on 11 April:

Based on my present knowledge I can see today clearly, severely and bitterly for me, that the entire ideology about the world in which I believed so firmly and unswervingly was based on completely wrong premises and had to absolutely collapse one day. And so my actions in the service of this ideology were completely wrong, even though I faithfully believed the idea was correct. Now it was very logical that strong doubts grew within me, and whether my turning away from my belief in God was based on completely wrong premises. It was a hard struggle. But I have again found my faith in my God.[25]

The same day in a farewell letter to his children, Höss told his eldest son:

Keep your good heart. Become a person who lets himself be guided primarily by warmth and humanity. Learn to think and judge for yourself, responsibly. Don't accept everything without criticism and as absolutely true... The biggest mistake of my life was that I believed everything faithfully which came from the top, and I didn't dare to have the least bit of doubt about the truth of that which was presented to me. ... In all your undertakings, don't just let your mind speak, but listen above all to the voice in your heart.[25]

Handwritten confession

The original affidavit, signed by Rudolf Höss, is displayed in a glass case in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. The photo displayed with the affidavit shows Hungarian Jewish women and children walking to one of the four gas chambers in the Birkenau death camp on 26 May 1944, carrying their baggage by hand.

References

Notes

- Graham Anderson (6 May 2014). "Rainer Höß: My Nazi family". Exberliner. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014 – via The Internet Archive.

- Harding, Thomas (September 2013). Hanns and Rudolf: The True Story of the German Jew Who Tracked Down and Caught the Kommandant of Auschwitz. Simon & Schuster. pp. 5, 288. ISBN 978-0-434-02236-6.

- Levy, Richard S. (2005). Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution (Two Vol. Set). ABC-CLIO. p. 324. ISBN 978-1-85109-439-4.

- Pressac & Pelt 1994, p. 209.

- Browning 2004, pp. 526–527.

- Piper, Franciszek & Meyer, Fritjof. "Overall analysis of the original sources and findings on deportation to Auschwitz". Review of the article "Die Zahl der Opfer von Auschwitz. Neue Erkentnisse durch neue Archivfunde", Osteuropa, 52, Jg., 5/2002, pp. 631–641.

- Fitzgibbon, Constantine; Hoess, Rudolf; Neugroschel, Joachim; Hoess, Rudolph; Levi, Primo (1 September 2000). Commandant of Auschwitz : The Autobiography of Rudolf Hoess. Phoenix. ISBN 978-1842120248.

- Michael Phayer (2000), The Catholic Church and the Holocaust: 1930–1965 Indiana University Press, ISBN 0253214718; p. 111.

- Rudolf Hess, Commandant of Auschwitz: The Autobiography of Rudolf Hess (Phoenix: Phoenix Press, 2000) pp. 15–27

- "Hedwig Höss-Hensel de vrouw van de kampcommandant en haar rol in Auschwitz. – heijmerikx.nl". www.heijmerikx.nl.

- Hilberg, Raul, Destruction of the European Jews (New York: Quadrangle Books, 1962), p. 575

- "Commandant of Auschwitz : The Autobiography of Rudolf Hoess", PDF-version as a comment of the PUBLISHER, not by himself, at PDF-page 47, actual page 39. Free download from www.bookyards.com

- This was written by himself during his last months in a Polish prison prior to his execution, but his claims have been examined and have not been questioned on this point. "Commandant of Auschwitz : The Autobiography of Rudolf Hoess" , pp. 43–44 or PDF version , pp. 51–52, free download at www.bookyards.com

- Shira Schoenberg (1990). "Martin Bormann". Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- Rudolf Höss (1958). Kommandant in Auschwitz. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. p. 37.

- Ludwig Pflücker; Jochanan Shelliem (2006). IAls Gefängnisarzt im Nürnberger Prozess: das Tagebuch des Dr. Ludwig Pflücker. Indianopolis: Jonas. p. 135. ISBN 978-3-89445-374-9.

- Evans 2003, pp. 219–220.

- Höss, Rudolf; Broad, Pery; Kremer, Johann Paul; Bezwińska, Jadwiga; Czech, Danuta (1984). KL Auschwitz seen by the SS. New York: H. Fertig. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-86527-346-7.

- "Hitler's Children", BBC documentary

- Evans 2005, p. 84.

- Rudolf Höss (1960). Commandant of Auschwitz: autobiography. World Pub. Co. p. 37.

- Prof. Douglas O. Linder, "Testimony of Rudolf Höß at the Nuremberg Trials, April 15, 1946" available online at Famous World Trials: The Nuremberg Trials: 1945–48, UMKC School of Law. OCLC 45390347

- Paul R. Bartrop (2014). Rudolf Hoess. Encountering Genocide: Personal Accounts from Victims, Perpetrators, and Witnesses. ABC-CLIO. p. 111. ISBN 978-1610693318. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- Evans 2008, p. 295.

- Hughes, John Jay (25 March 1998). A Mass Murderer Repents: The Case of Rudolf Hoess, Commandant of Auschwitz. Archbishop Gerety Lecture at Seton Hall University. PDF file, direct download.

- BBC History of World War II. Auschwitz; Inside the Nazi State.

- "Jozef Paczynski, holocaust survivor – obituary". Daily Telegraph. 5 May 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- Pressac, Jean-Claude (1989). AUSCHWITZ: Technique and Operation of the Gas Chambers p. 132. First experimental gassing in Block 11.

- Commandant of Auschwitz (2000), pp. 106–157, and Appendix 1, pp. 183–200.

- Gilbert (1995), pp. 249–50.

- Hoess Affidavit for Nuremberg Trial at Fordham.edu

- Pauer-Studer, Herlinde; Velleman, J. David (2015), "Rudolf Höss and Eleonore Hodys", Konrad Morgen, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 112–114, doi:10.1057/9781137496959_17, ISBN 9781349505043

- Langbein, Hermann (2004). People in Auschwitz. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 311, 411–413. ISBN 9780807828168.

- Romanov, Sergey (8 November 2009). "Holocaust Controversies: War-time German document mentioning Auschwitz gassings: testimony of Eleonore Hodys". Holocaust Controversies. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Jozef Boszko, Encyclopedia of the Holocaust vol. 2, p. 692

- Wilkinson, Alec, "Picturing Auschwitz", The New Yorker, 17 March 2008, pp. 50–54.

- "Nazi hunter: Exploring the power of secrecy and silence". The Globe and Mail. 7 November 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- Harding, Thomas (31 August 2013). "Was my Jewish great-uncle a Nazi hunter? by Thomas Harding". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- "Hiding in N. Virginia, a daughter of Auschwitz by Thomas Harding". washington post. 7 September 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- Overy, Richard (9 September 2013). "Hanns and Rudolf by Thomas Harding, review". The Telegraph. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- "Hanns und Rudolf". ORF.at (in German). 29 August 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Zimmerman, John C. (11 February 1999). "How Reliable are the Höss Memoirs?". Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Volume 11. pp. 396–422. Monday, 15 April 1946

- Hoess, Rudolph. Commandant of Auschwitz: The Autobiography of Rudolph Hoess. Translated by Constantine FitzGibbon. Ohio: World Publishing, 1959. p. 194

- Kevin Jon Heller. The Nuremberg Military Tribunals and the Origins of International Criminal Law. Oxford University Press. 2011. p. 149.

- Modern History Sourcebook: Rudolf Hoess, Commandant of Auschwitz: Testimony at Nuremberg, 1946

- Applebome, Peter (14 March 2007). "Veteran of the Nuremberg Trials Can't Forget Dialogue With Infamy". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- Death Dealer: The Memoirs of the SS Kommandant at Auschwitz, trans. Andrew Dollinger. Buffalo (NY): Prometheus Books, 1992, p. 40.

- Death Dealer: The Memoirs of the SS Kommandant at Auschwitz, trans. Andrew Dollinger. Idem, pp. 179–180.

- "[PDF] Commandant Of Auschwitz – Free eBooks – Bookyards.com – The Library To The World". www.bookyards.com.

- Page 16 of this PDF-file (in book form of the English version page 8), Translator's note, states "The original documents are the property of the High Commission for the Examination of Hitlerite Crimes in Poland (Glownej Komisji Badania Zbrodni Hitlercwsldch w Polsce),but the Auschwitz Museum made a photostat available to Dr.Broszat, who has fully tested its authenticity"

- Gilbert (1995), p. 260

- PAP (16 April 2012). Kat Hoess nawrócił się w Wadowicach (Executioner's Repentance in Wadowice). (in Polish)

Bibliography

- Browning, Christopher R. (2004). The Origins of the Final Solution : The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 – March 1942. Comprehensive History of the Holocaust. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1327-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Richard J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-303469-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Richard J. (2005). The Third Reich in Power. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-303790-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich At War. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-311671-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gilbert, Gustave. [1947] 1995. Nuremberg Diary. USA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80661-2.

- Harding, Thomas (8 September 2013). "The Kommandant's Daughter". Washington Post Magazine. pp. 12–17.

- Harding, Thomas (September 2013). Hanns and Rudolf: The True Story of the German Jew Who Tracked Down and Caught the Kommandant of Auschwitz. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-434-02236-6.

- Höß, Rudolf. Death Dealer: The Memoirs of the SS Kommandant at Auschwitz. edited by Steven Paskuly and translated by Andrew Pollinger. Buffalo, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 1992. ISBN 978-0-87975-714-4. Google Books preview.

- Höß, Rudolf. Kommandant in Auschwitz; autobiographische Aufzeichnungen. Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Zeitgeschichte. Quellen und Darstellungen zur Zeitgeschichte, Bd. 5. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1958. (in German)

- Höß, Rudolf. Commandant of Auschwitz: The Autobiography of Rudolf Hoess. (Constantine FitzGibbon, trans.) London: Phoenix Press, 2000. ISBN 1-84212-024-7. (A different translation of Kommandant in Auschwitz.)

- Pressac, Jean-Claude; Pelt, Robert-Jan van (1994). "The Machinery of Mass Murder at Auschwitz". In Gutman, Yisrael; Berenbaum, Michael (eds.). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 183–245. ISBN 978-0-253-32684-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ravenswood, Linda, Frau Kommandant Hoess' Pink Cardigan, Rivets Literary Magazine, 2010.

- SS Personnel Service Record of Rudolf Höss, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland, US.

Further reading

- Fest, Joachim C. and Bullock, Michael (trans.) "Rudolf Höss – The Man from the Crowd" in The Face of the Third Reich New York: Penguin, 1979 (orig. published in German in 1963), pp. 415–432. ISBN 978-0201407143.

External links

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by None |

Commandant of Auschwitz 4 May 1940 – November 1943 |

Succeeded by SS-Obersturmbannführer Arthur Liebehenschel |

| Preceded by SS-Obersturmbannführer Arthur Liebehenschel |

Commandant of Auschwitz 8 May 1944 – 18 January 1945 |

Succeeded by None |