The Holocaust in Estonia

The Holocaust in Estonia refers to the Nazi crimes during the occupation of Estonia by Nazi Germany. Prior to the war, there were approximately 4,300 Estonian Jews. After the Soviet 1940 occupation about 10% of the Jewish population was deported to Siberia, along with other Estonians. About 75% of Estonian Jews, aware of the fate that awaited them from Nazi Germany, escaped to the Soviet Union; virtually all of those who remained (between 950 and 1,000 people) were killed by Einsatzgruppe A and local collaborators before the end of 1941. Roma people of Estonia were also murdered and enslaved by the Nazi occupiers and their collaborators. The Nazis and their allies also killed around 6,000 ethnic Estonians and 1,000 ethnic Russians who were accused of being communist sympathizers or the relatives of communist sympathizers. In addition around 15,000 Soviet prisoners-of-war and Jews from other parts of Europe were killed in Estonia during the German occupation.[1]

Jewish life pre-Holocaust

Prior to World War II, Jewish life flourished with the level of cultural autonomy accorded being the most extensive in all of Europe, giving full control of education and other aspects of cultural life to the local Jewish population.[2] In 1936, the British-based Jewish newspaper The Jewish Chronicle reported that "Estonia is the only country in Eastern Europe where neither the Government nor the people practice any discrimination against Jews and where Jews are left in peace and are allowed to lead a free and unmolested life and fashion it in accord with their national and cultural principles."[3]

Murder of Jewish population

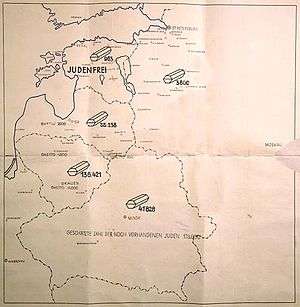

Round-ups and killings of the remaining Jews began immediately as the first stage of Generalplan Ost which would require the "removal" of 50% of Estonians.[4]:54 Undertaken by the extermination squad Einsatzkommando (Sonderkommando) 1A under Martin Sandberger, part of Einsatzgruppe A led by Walter Stahlecker, who followed the arrival of the first German troops on July 7, 1941. Arrests and executions continued as the Germans, with the assistance of local collaborators, advanced through Estonia. Estonia became a part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland. A Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police) was established for internal security under the leadership of Ain-Ervin Mere in 1942. Estonia was declared Judenfrei quite early by the German occupation regime at the Wannsee Conference.[5] The Jews who had remained in Estonia (929 according to the most recent calculation[6]) were killed.[7] Fewer than a dozen Estonian Jews are known to have survived the war in Estonia.[6]

German policy toward the Jews in Estonia

The Estonian state archives contain death certificates and lists of Jews shot dated July, August, and early September 1941. For example, the official death certificate of Rubin Teitelbaum, born in Tapa on January 17, 1907, states laconically in a form with item 7 already printed with only the date left blank: "7. By a decision of the Sicherheitspolizei on September 4, 1941, condemned to death, with the decision being carried out the same day in Tallinn." Teitelbaum's crime was "being a Jew" and thus constituting a "threat to the public order".

On September 11, 1941 an article entitled "Juuditäht seljal" – "A Jewish Star on the Back" appeared in the Estonian mass-circulation newspaper Postimees. It stated that Dr. Otto-Heinrich Drechsler, the High Commissioner of Ostland, had proclaimed ordinances in accordance with which all Jewish residents of Ostland from that day onward had to wear visible yellow six-pointed Star of David at least 10 cm (4 in). in diameter on the left side of their chest and back.

On the same day regulations[8] issued by the Sicherheitspolizei were delivered to all local police departments proclaiming that the Nuremberg Laws were in force in Ostland, defining who is a Jew, and what Jews could and could not do. Jews were prohibited from changing their place of residence, walking along the sidewalk, using any means of transportation, going to theatres, museums, cinema, or school. The professions of lawyer, physician, notary, banker, or real estate agent were declared closed to Jews, as was the occupation of street hawker. The regulations also declared that the property and homes of Jewish residents were to be confiscated. The regulations emphasized that work to this ends was to be begun as soon as possible, and that lists of Jews, their addresses, and their property were to be completed by the police by September 20, 1941.

These regulations also provided for the establishment of a concentration camp near the south-eastern Estonian city of Tartu. A later decision provided for the construction of a Jewish ghetto near the town of Harku, but this was never built, a small concentration camp being built there instead. The Estonian State Archives contain material pertinent to the cases of about 450 Estonian Jews. They were typically arrested either at home or in the street, taken to the local police station, and charged with the 'crime' of being Jews. They were either shot outright or sent to concentration camp and shot later. An Estonian woman, E. S. describes the arrest of her Jewish husband as follows:[9]

As my husband did not go out of the house, I was the one to go to town every day to see what was going on. I was very frightened when I saw a poster at the corner of Vabaduse Square and Harju Street calling for people to show where the apartments of Jews were located. On that fatal day of September 13, I went out again because the weather was fine but I remember being very worried. I rushed home and when I got there and heard some voices in our apartment I had a foreboding that something bad had happened. There were two men in our apartment from the Selbstschutz who said they were taking my husband to the police station. I ran after them and went to the chief officer and asked for permission to see my husband. The chief officer said that he could not give me permission but added, in a low voice, that I should come the next morning when the prisoners would be taken to prison and perhaps I could see my husband in the corridor. I returned the next morning as I had been advised, and it was the last time I saw my husband. On September 15 I went to the German Sicherheitspolizei on Tõnismägi in an attempt to get information about my husband. I was told he had been shot. I asked the reason since he had not been a communist but a businessman, The answer was: "Aber er war doch ein Jude." [But he was a Jew.].

Foreign Jews

After the invasion of the Baltic States, it was the intention of the Nazi government to use the Baltic countries as their main area of mass genocide. Consequently, Jews from countries outside the Baltics were deported there to be killed.[10] An estimated 10,000 Jews were killed in Estonia after having been deported to camps there from elsewhere in Eastern Europe. The Nazi regime also established 22 concentration camps in occupied Estonian territory for foreign Jews, where they would used as slave laborers. The largest, Vaivara concentration camp, served as a transit camp and processed 20,000 Jews from Latvia and the Lithuanian ghettos.[11] Usually able-bodied men were selected to work in the oil shale mines in northeastern Estonia. Women, children, and old people were killed on arrival.

At least two trainloads of Central European Jews were deported to Estonia and were killed on arrival at the Kalevi-Liiva site near Jägala concentration camp.[5]

Murder of foreign Jews at Kalevi-Liiva

According to testimony of the survivors, at least two transports with about 2,100–2,150 Central European Jews,[12] arrived at the railway station at Raasiku, one from Theresienstadt (Terezin) with Czechoslovakian Jews and one from Berlin with German citizens. Around 1,700–1,750 people were immediately taken to an execution site at the Kalevi-Liiva sand dunes and shot.[12] About 450 people were selected for work at the Jägala concentration camp.[12][13]

Transport Be 1.9.1942 from Theresienstadt arrived at the Raasiku station on September 5, 1942, after a five-day trip.[14][15] According to testimony by Ralf Gerrets, one of the accused at the war crimes trials in 1961, eight busloads of Estonian auxiliary police had arrived from Tallinn.[15] The selection process was supervised by Ain-Ervin Mere, chief of Security Police in Estonia; those transportees not selected for slave labor were sent by bus to a killing site near the camp. Later the police,[15] in teams of 6 to 8 men,[12] killed the Jews by machine gun fire. During later investigations, however, some guards of camp denied the participation of police and said that executions were done by camp personnel.[12] On the first day, a total of 900 people were murdered in this way.[12][15] Gerrets testifies that he had fired a pistol at a victim who was still making noises in the pile of bodies.[15][16] The whole operation was directed by SS commanders Heinrich Bergmann and Julius Geese.[12][15] Few witnesses pointed out Heinrich Bergmann as the key figure behind the extermination of Estonian gypsies. In the case of Be 1.9.1942, the only ones chosen for labor and to survive the war were a small group of young women who were taken through a series of concentration camps in Estonia, Poland and Germany to Bergen-Belsen, where they were liberated.[17] Camp commandant Laak used the women as sex slaves, killing many after they had outlived their usefulness.[13][18]

A number of foreign witnesses were heard at the post-war trials in Soviet Estonia, including five women who had been transported on Be 1.9.1942 from Theresienstadt.[15]

The accused Mere, Gerrets and Viik actively participated in crimes and mass killings that were perpetrated by the Nazi invaders on the territory of the Estonian SSR. In accordance with the Nazi racial theory, the Sicherheitspolizei and Sicherheitsdienst were instructed to exterminate the Jews and Gypsies. To that end, during August and September of 1941, Mere and his collaborators set up a death camp at Jägala, 30 km (19 mi) from Tallinn. Mere put Aleksander Laak in charge of the camp; Ralf Gerrets was appointed his deputy. On September 5, 1942, a train with approximately 1,500 Czechoslovak citizens arrived at the Raasiku railway station. Mere, Laak and Gerrets personally selected who of them should be executed and who should be moved to the Jägala death camp. More than 1,000 people, mostly children, the old, and the infirm, were transported to a wasteland at Kalevi-Liiva, where they were monstrously executed in a special pit. In mid-September, the second troop train with 1,500 prisoners arrived at the railway station from Germany. Mere, Laak, and Gerrets selected another thousand victims, who were then condemned by them to extermination. This group of prisoners, which included nursing women and their new-born babies, were transported to Kalevi-Liiva where they were killed.

In March 1943, the personnel of the Kalevi-Liiva camp executed about fifty Gypsies, half of whom were under 5 years of age. Also were executed 60 Gypsy children of school age...[19]

Romani people

A few witnesses pointed out Heinrich Bergmann as the key figure behind the extermination of Estonian Roma people.[17]

Estonian collaboration

The Germans recruited tens of thousands of native Estonians into the Waffen SS and the Wehrmacht.[20] Formations of note in such forces were the Estonian Legion, the 3rd Estonian SS Volunteer Brigade, and the 20th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Estonian) among others.

Units of the Eesti Omakaitse (Estonian Home Guard; approximately 1000 to 1200 men) were directly involved in criminal acts, taking part in the round-up of 200 Roma people and 950 Jews.[1] Units of Estonian Auxiliary Police participated in the extermination of Jews in the Pskov region of Russia and provided guards for concentration camps for Jews and Soviet POWs in Jägala, Vaivara, Klooga, and Lagedi.[1]

The final acts of liquidating the camps, such as Klooga, which involved the mass-shooting of roughly 2,000 prisoners, were carried out by Estonian SS units belonging to the 20th SS Division and Schutzmannschaftsbataillon of the KdS. Survivors report that, during these last days before liberation, when Jewish slave labourers were visible, the Estonian population in part attempted to help the Jews by providing food and other types of assistance."[1][21]

War crimes trials

Four Estonians deemed most responsible for the murders at Kalevi-Liiva were accused at the war crimes trials in 1961. Two were later executed, while the Soviet occupation authorities were unable to press charges against the other two due to the fact that they lived in exile.[22] There have been 7 known ethnic Estonians (Ralf Gerrets, Ain-Ervin Mere, Jaan Viik, Juhan Jüriste, Karl Linnas, Aleksander Laak and Ervin Viks) who have faced trials for crimes against humanity committed during the Nazi occupation in Estonia. The accused were charged with murdering up to 5,000 German and Czechoslovakian Jews and Romani people near the Kalevi-Liiva concentration camp in 1942–1943. Ain-Ervin Mere, commander of the Estonian Security Police (Group B of the Sicherheitspolizei) under the Estonian Self-Administration, was tried in absentia. Before the trial, Mere had been an active member of the Estonian community in England, contributing to Estonian language publications.[23] At the time of the trial, however, he was being held in custody in England, having been accused of murder. He was never deported[24] and died a free man in England in 1969. Ralf Gerrets, the deputy commandant at the Jägala camp. Jaan Viik, (Jan Wijk, Ian Viik), a guard at the Jägala labor camp, out of the hundreds of Estonian camp guards and police, was singled out for prosecution due to his particular brutality.[19] Witnesses testified that he would throw small children into the air and shoot them. He did not deny the charge.[16] A fourth accused, camp commandant Aleksander Laak (Alexander Laak), was discovered living in Canada, but committed suicide before he could be brought to trial.

In January 1962, another trial was held in Tartu. Juhan Jüriste, Karl Linnas and Ervin Viks were accused of murdering 12,000 civilians in the Tartu concentration camp.

Number of victims

Soviet-Estonian era sources estimate the total number of Soviet citizens and foreigners to be murdered in Nazi-occupied Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic to be 125,000.[25][26][27][28][29] The bulk of this number consists Jews from Central and Western Europe and Soviet prisoners-of-war killed or starved to death in prisoner-of-war camps on Estonian territory.[28][29] The Estonian History Commission estimates the total number of victims to be roughly 35,000, consisting of the following groups:[1]

- 1000 Estonian Jews,

- about 10,000 foreign Jews,

- 1000 Estonian Roma,

- 7000 other Estonians,

- 15,000 Soviet POWs.

The number of Estonian Jews killed is less than 1,000; the German Holocaust perpetrators Martin Sandberger and Walter Stahlecker cite the numbers 921 and 963 respectively. In 1994 Evgenia Goorin-Loov calculated the exact number to be 929.[6]

Modern memorials

Since the reestablishment of the Estonian independence, markers were put in place for the 60th anniversary of the mass executions that were carried out at the Lagedi, Vaivara and Klooga (Kalevi-Liiva) camps in September 1944.[30] On February 5, 1945 in Berlin, Ain Mere founded the Eesti Vabadusliit together with SS-Obersturmbannführer Harald Riipalu.[31] He was sentenced to the capital punishment during the Holocaust trials in Soviet Estonia but was not extradited by Great Britain and died there in peace. In 2002 the Government of the Republic of Estonia decided to officially commemorate the Holocaust. In the same year, the Simon Wiesenthal Center had provided the Estonian government with information on alleged Estonian war criminals, all former members of the 36th Estonian Police Battalion. In August 2018 it was reported that the memorial at Kalevi-Liiva was defaced.[32]

Collaborators

- Ralf Gerrets

- Juhan Jüriste

- Friedrich Kurg[33][34]

- Aleksander Laak

- Karl Linnas

- Ain-Ervin Mere

- Hjalmar Mäe

- Jaan Viik

- Ervin Viks

Organizations

- Einsatzgruppe A

- Estonian Auxiliary Police

- Omakaitse

- Ordnungspolizei

- Sonderkommando 1a

- Sicherheitspolizei

Concentration camps

KZ-Stammlager

KZ-Außenlager

- KZ Aseri

- KZ Auvere

- KZ Erides

- KZ Goldfields (Kohtla)

- KZ Ilinurme

- KZ Jewe

- KZ Kerestowo (Karstala in Viru Ingria, now in Gatchinsky District)

- KZ Kiviöli

- KZ Kukruse

- KZ Kunda

- KZ Kuremaa

- KZ Lagedi

- KZ Klooga, Lodensee. Commandant SS-Untersturmführer Wilhelm Werle. (b. 1907, d. 1966),;[35] September 1943 – September 1944. There were held 2 000 – 3 000 prisoners, most of them the Lithuanian Jews. When the Red Army approached, SS-men shot the 2 500 prisoners on September 19, 1944 and burned most of the bodies. The fewer than 100 prisoners succeeded in surviving by hiding. There is a monument on the location of the concentration camp.

- KZ Narwa

- KZ Pankjavitsa, Pankjewitza. It was situated app. 15 km south of the village of Pankjavitsa near the hamlet of Roodva in the former Estonian province of Petserimaa. Since 1945 Russia occupies a large part of this province including Roodva/Rootova. The camp was established in November 1943. On 11 November that year 250 prisoners from Klooga arrived. Their accommodations were barracks. Already in January 1944 the camp was shut down and the inmates were relocated to Kūdupe (in Latvia near the Estonian border), Petseri and Ülenurme. Likely the camp was closed after some kind of work was finished. It was affiliated to the Vaivara camp.[36]

- KZ Narwa-Hungerburg

- KZ Putki (in Piiri Parish, near Slantsy)

- KZ Reval (Ülemiste?)

- KZ Saka

- KZ Sonda

- KZ Soski (in Vasknarva Parish)

- KZ Wiwikond

- KZ Ülenurme

Arbeits- und Erziehungslager

Other concentration camps

References

- "Report Phase II: The German Occupation of Estonia 1941–1944" (PDF). Estonian International Commission for Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011. Retrieved June 2016. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Spector, Shmuel; Geoffrey Wigoder (2001). The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust, Volume 3. NYU Press. p. 1286. ISBN 978-0-8147-9356-5.

- "Estonia, an oasis of tolerance". The Jewish Chronicle. September 25, 1936. pp. 22–3.

- Buttar, Prit (May 21, 2013). Between Giants. ISBN 9781780961637.

- Museum of Tolerance Multimedia Learning Center Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Hietanen, Leena (April 19, 1998). "Juutalaisten kohtalo". Turun Sanomat (in Finnish). Archived from the original on July 8, 2011.

- "Küng, Andres, Communism and Crimes against Humanity in the Baltic states, A Report to the Jarl Hjalmarson Foundation seminar on April 13, 1999". rel.ee. Archived from the original on March 1, 2001. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ERA.F.R-89.N.1.S.1.L.2

- Quoted in Eugenia Gurin-Loov, Holocaust of Estonian Jews 1941, Eesti Juudi Kogukond, Tallinn 1994: pg. 224

- The Holocaust in the Baltics Archived March 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine at University of Washington

- "Concentration Camps: Vaivara". Jewish Virtual Library. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved June 2016. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Jägala laager ja juutide hukkamine Kalevi-Liival Archived September 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine – Eesti Päevaleht March 30, 2006 (in Estonian)

- "Girls Forced Into Orgies – Then Slain, Court Told". The Ottawa Citizen. Ottawa. March 8, 1961. p. 7. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- "THE GENOCIDE OF THE CZECH JEWS". old.hrad.cz. Archived from the original on May 26, 2011. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- De dödsdömda vittnar Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (Transport Be 1.9.1942 Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine) (in Swedish)

- "Estonian policemen stand trial for war crimes". ushmm.org. Video footage at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on June 22, 2007. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- "From Ghetto Terezin to Lithuania and Estonia". bterezin.org.il. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- Omakaitse omakohus Archived June 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine – JERUUSALEMMA SÕNUMID (in Estonian)

- Weiss-Wendt, Anton (2003). Extermination of the Gypsies in Estonia during World War II: Popular Images and Official Policies Archived February 20, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Holocaust and Genocide Studies 17.1, 31–61.

- Name, Author. "The 3rd Estonian SS Volunteer Brigade". www.eestileegion.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- Birn, Ruth Bettina (2001), Collaboration with Nazi Germany in Eastern Europe: the Case of the Estonian Security Police Archived June 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Contemporary European History10.2, 181–198. P. 190–191.

- Estonia at Archived November 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Jewish Virtual Library

- Estonian State Archives of the Former Estonian KGB (State Security Committee) records relating to war crime investigations and trials in Estonia, 1940–1987 (manuscript RG-06.026) – United States Holocaust Memorial Museum – document available on-line through this query page Archived June 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine using document id RG-06.026 – Also available at Axis History Forum Archived December 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine – This list includes the evidence presented at the trial. It list as evidence several articles by Mere in Estonian language newspapers published in London

- "Mainstream". Masses & Mainstream. May 7, 1961. Retrieved May 7, 2018 – via Google Books.

- Fraser, David (2005). Law after Auschwitz: towards a jurisprudence of the Holocaust. Carolina Academic Press. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-89089-243-5. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018.

- Edelheit, Hershel; Edelheit, Abraham J. (1995). Israel and the Jewish world, 1948–1993: a chronology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-313-29275-0. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018.

- "ESTONIANS GIVEN DEATH Russians Convict Them Of Aiding Nazi Exterminations". The Sun. Baltimore. March 12, 1961. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012.

- Laur, Mati; Lukas, Tõnis; Mäesalu, Ain; Pajur, Tõnu; Tannberg, T. (2002). Eesti ajalugu [The History of Estonia] (in Estonian) (2nd ed.). Tallinn: Avita. p. 270. ISBN 9789985206065. Lay summary (PDF).

- Frucht, Richard C. (2005). "The loss of independence (1939–1944)". Eastern Europe: an introduction to the people, lands, and culture – Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 80. ISBN 1-57607-800-0. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018.

- "Holocaust Markers, Estonia". heritageabroad.gov. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- Veebruari sündmused Archived March 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (in Estonian)

- https://news.err.ee/855579/holocaust-victim-memorials-vandalised-at-kalevi-liiva

- "* 1941. aasta suvesõda: omakaitselased keetsid punaseid elusalt". wordpress.com. July 3, 2007. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- Andrei Hvostov, Jakobsoni komisjon Augeiase tallis

- "Wilhelm Werle". Axis History Forum. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved June 2016. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Pankjewitza (Pankjavitsa) by Ruth Bettina Birn, in: Der Ort des Terrors. Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager Band. 8: Riga-Kaiserwald, Warschau, Vaivara, Kauen (Kaunas), Plaszów, Kulmhof/Chelmno, Belzéc, Sobibór, Treblinka. Gebundene Ausgabe – 24. Oktober 2008 von Wolfgang Benz (Herausgeber), Barbara Distel (Herausgeber), Angelika Königseder (Bearbeitung). P. 173.

- "Quelle und weiterführende Hinweise]. Siehe auch die [http://www.bundesrecht.juris.de/begdv_6/BJNR002330967.html Sechste Verordnung zur Durchführung des Bundesentschädigungsgesetzes (6. DV-BEG)". keom.de. Retrieved May 7, 2018. External link in

|title=(help) - "Kultuur ja Elu - kultuuriajakiri". kultuur.elu.ee. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- Haakristi haardes.Tallinn 1979, lk 84

- Haakristi haardes.Tallinn 1979, lk 68

- Haakristi haardes.Tallinn 1979, lk 66

- Haakristi haardes.Tallinn 1979, lk 64

- Haakristi haardes.Tallinn 1979, lk 69

Bibliography

- 12000: Tartus 16.-20.jaanuaril 1962 massimõrvarite Juhan Jüriste, Karl Linnase ja Ervin Viksi üle peetud kohtuprotsessi materjale. Karl Lemmik and Ervin Martinson. Eesti Riiklik Kirjastus. 1962

- Ants Saar, Vaikne suvi vaikses linnas. Eesti Raamat. 1971

- "Eesti vaimuhaigete saatus Saksa okupatsiooni aastail (1941–1944)", Eesti Arst, nr. March 3, 2007

- Ervin Martinson. Elukutse – reetmine. Eesti Raamat. 1970

- Ervin Martinson. Haakristi teenrid. Eesti Riiklik Kirjastus. 1962

- Inimesed olge valvsad. Vladimir Raudsepp. Eesti Riiklik Kirjastus. 1961

- Pruun katk: Dokumentide kogumik fašistide kuritegude kohta okupeeritud Eesti NSV territooriumil. Ervin Martinson and A. Matsulevitš. Eesti Raamat. 1969

- SS tegutseb: Dokumentide kogumik SS-kuritegude kohta. Eesti Riiklik Kirjastus. 1963

Further reading

- Weiss-Wendt, Anton (2009). Murder Without Hatred: Estonians and the Holocaust. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-3228-3.