Central Java

Central Java (Indonesian: Jawa Tengah; Javanese: Jåwå Tengah; Hanacaraka: ꦗꦮꦠꦼꦔꦃ) is a province of Indonesia, located in the middle of the island of Java. Its administrative capital is Semarang. It is bordered by West Java in the west, the Indian Ocean and the Special Region of Yogyakarta in the south, East Java in the east, and the Java Sea in the north. It has a total area of 32,548 km², with a population of 34,552,500 in mid 2019,[2] making it the third-most populous province in both Java and Indonesia after West Java and East Java. The province also includes the island of Nusakambangan in the south (close to the border of West Java), and the Karimun Jawa Islands in the Java Sea. Central Java is also a cultural concept that includes the Special Region and city of Yogyakarta. However, administratively the city and its surrounding regencies have formed a separate special region (equivalent to a province) since the country's independence, and is administrated separately. Although known as the "heart" of Javanese culture, there are several other non-Javanese ethnic groups, such as the Sundanese on the border with West Java. Chinese Indonesians, Arab Indonesians, and Indian Indonesians are also scattered throughout the province.

Central Java Jawa Tengah | |

|---|---|

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Location of Central Java in Indonesia | |

| Coordinates: 7°30′S 110°00′E | |

| Established | 19 August 1945[1] |

| Capital and largest city | Semarang |

| Government | |

| • Body | Central Java Provincial Government |

| • Governor | Ganjar Pranowo |

| • Vice Governor | Taj Yasin Maimoen |

| Area | |

| • Total | 32,800.69 km2 (12,664.42 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 3,428 m (11,247 ft) |

| Population (mid 2019)[2] | |

| • Total | 34,552,500 |

| • Rank | 3rd in Indonesia |

| • Density | 1,100/km2 (2,700/sq mi) |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic groups | 97.9% Javanese 1.4% Sundanese 0.4% Chinese 0.3% other[3] |

| • Religion | 95.7% Islam 4.12% Christianity 0.18% other (including Kejawen) |

| • Languages | Indonesian (official) Javanese (native) Sundanese (minority) |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (Indonesia Western Time) |

| ISO 3166 code | ID-JT |

| HDI | |

| HDI rank | 13th in Indonesia (2019) |

| GRP Nominal | |

| GDP PPP (2019) | |

| GDP rank | 4th in Indonesia (2019) |

| Nominal per capita | US$ 2,775 (2019)[4] |

| PPP per capita | US$ 9,123 (2019)[4] |

| Per capita rank | 25th in Indonesia (2019) |

| Website | jatengprov |

The province has been inhabited by humans since the prehistoric-era. Remains of a Homo erectus, known as "Java Man", were found along the banks of the Bengawan Solo River, and date back to 1.7 million years ago.[5] What is present-day Central Java was once under the control of several Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms, Islamic sultanates, and the Dutch East Indies colonial government. Central Java was also the centre of the Indonesian independence movement. As the majority of modern-day Indonesians are of Javanese descent, both Central Java and East Java have a major impact on Indonesia's social, political, and economic life.

History

Etymology

The origin of the name "Java" can be traced from the Sanskrit chronicle which mentions the existence of an island called yavadvip(a) (dvipa means "island", and yava means "barley" or also "grain").[5][6] Are these grains a millet (Setaria italica) or rice, both of which have been widely found on this island in the days before the entry of Indian influence.[7] It is possible that this island has many previous names, including the possibility of originating from the word jaú which means "far away". Yavadvipa is mentioned in one of the Indian epic, Ramayana. According to the epic, Sugriva, the commander of the wanara (ape man) from Sri Rama's army, sent his envoy to Yavadvip ("Java Island") to look for the Hindu goddess Sita.[8]

Another possible assumption is that the word "Java" comes from the root words in a Proto-Austronesian language, Awa or Yawa (Similar to the words Awa'i (Awaiki) or Hawa'i (Hawaiki) used in Polynesia, especially Hawaii) which means "home".[9]

An island called Iabadiu or Jabadiu is mentioned in Ptolemy's work called Geographia which was made around 150 AD during the era of the Roman Empire. Iabadiu is said to mean "island of barley", also rich in gold, and has a silver city called Argyra at its western end. This name mentioned Java, which most likely origins from the Sanskrit term Java-dvipa (Yawadvipa).[10]

Chinese records from the Songshu and the Liangshu referred to Java as She-po (5th century AD), He-ling (640-818 AD), then called it She-po again until the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), where they began to call Zhao-Wa.[11] In the book Yingyai Shenglan, written by the Chinese Ming explorer Ma Huan, the Chinese call Java as Chao-Wa, and it was once called the She-pó (She-bó).[12] When Giovanni de' Marignolli returned from China to Avignon, he stopped at the kingdom of Saba, which he said had many elephants and was led by a queen; this name Saba might be his interpretation of She-bó.[13]

Pre-historic era

Java has been inhabited by humans or their ancestors (hominina) since prehistoric times. In Central Java and the adjacent territories in East Java remains known as "Java Man" were discovered in the 1890s by the Dutch anatomist and geologist Eugène Dubois. It belongs to the species Homo erectus,[14] and are believed to be about 1.7 million years old.[14] The Sangiran site is an important prehistoric site on Java.

Around 40,000 years ago, Australoid peoples related to modern Australian Aboriginals and Melanesians colonised Central Java. They were assimilated or replaced by Mongoloid Austronesians by about 3,000 BC, who brought with them technologies of pottery, outrigger canoes, the bow and arrow, and introduced domesticated pigs, fowls, and dogs. They also introduced cultivated rice and millet.[15]

Hindu-Buddhist and Islamic era

Recorded history began in what is now Central Java in the 7th century AD. The writing, as well as Hinduism and Buddhism, were brought by the Indians from South Asia, at the time of Central Java was a centre of power in Java back then. In 664 AD, the Chinese monk Hui-neng visited the Javanese port city he called Hēlíng (訶陵) or Ho-ling, where he translated various Buddhist scriptures into Chinese with the assistance of the Javanese Buddhist monk Jñānabhadra. It is not precisely known what is meant by the name Hēlíng. It used to be considered the Chinese transcription of Kalinga but it now most commonly thought of as a rendering of the name Areng. Hēlíng is believed to be located somewhere between Semarang and Jepara.

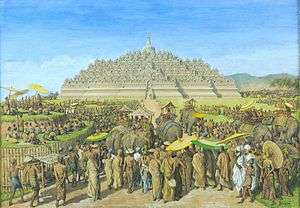

The first dated inscription in Central Java was the Canggal from 732 AD (or 654 Saka). This inscription, which hailed from Kedu, is written in Sanskrit in Pallava script. It is written that a Shaivite king named Sri Sanjaya established a kingdom called Mataram. Under the reign of Sanjaya's dynasty, several monuments such as the Prambanan temple complex were built. At the same time, a competing dynasty Sailendra arose, which adhered to Buddhism and built the Borobudur temple. After 820 AD, there was no more mention of the Hēlíng in Chinese records. This fact coincides with the overthrow of the Sailendras by the Sanjayas who restored Shaivism as the dominant religion. In the middle of the 10th century, however, the centre of power moved to eastern Java. Raden Wijaya founded the Majapahit Empire, and it reached its peak during the reign of Hayam Wuruk (m. 1350–1389). The kingdom claimed sovereignty over the entire Indonesian archipelago, although direct control tended to be limited to Java, Bali and Madura. Gajah Mada was a military leader during this time, who led numerous territorial conquests. The kingdoms in Java had previously based their power on agriculture, but Majapahit had succeeded in seizing ports and shipping lanes, in a bid to become the first commercial empire on Java. The empire suffered a setback after the death of Hayam Wuruk and the entry of Islam into the archipelago.

In the late 16th century, the development of Islam had surpassed Hinduism and Buddhism as the dominant religion in Java. The emergence of the Islamic kingdoms in Java is also inseparable from the role of Walisongo. At first, the spread of Islam was quick and was accepted by ordinary people, until the entrance of da'wah and was carried out by the rulers of the island. The Sultanate of Demak was the first recorded Islamic kingdom in Java, first led by one of the descendants of the Majapahit emperor Raden Patah, who converted to Islam. During this period, Islamic kingdoms began to develop from Pajang, Surakarta, Yogyakarta, Cirebon, and Banten to establish their power. Another Islamic kingdom, the Sultanate of Mataram, grew into a dominant force from the central and eastern parts of Java. The rulers of Surabaya and Cirebon were subdued under the rule of Mataram, and it was only Mataram and Banten Sultanates that were left behind when the Dutch arrived in the early 17th century. Some kingdoms of Islamic heritage in Java can still be found in several cities, such as Surakarta and Yogyakarta with two kingdoms each, Kasunanan and Mangkunegaran, and the Yogyakarta Sultanate and Pakualaman, respectively.

Dutch colonial rule

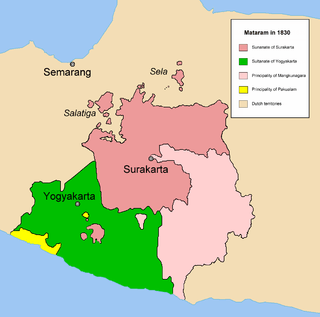

By the late 16th century, European traders began to frequent central Javanese ports. The Dutch established a presence in the region through their East India Company. Following the collapse of Demak, Mataram under the reign of Sultan Agung was able to conquer almost all of Java and beyond by the 17th century, but internal disputes and Dutch intrigues forced it to cede more land to the Dutch. These cessions finally led to several partitions of Mataram. The first was after the 1755 Treaty of Giyanti, which divided the kingdom in two, the Sultanates of Surakarta and Yogyakarta. In a few years, the former was divided again with the establishment of the Mangkunegaran following the 1757 Treaty of Salatiga.

During the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, Central Java as a Dutch colony was handed over to the British. In 1813, the Sultanate of Yogyakarta was also divided with the establishment of the Pakualaman. Following the departure of the British, the Dutch returned as stipulated in the Congress of Vienna. The Java War between 1825 and 1830 ravaged Central Java, which resulted in a consolidation of the Dutch power. The power and the territories of the already divided Mataram were greatly reduced. After the war, the Netherlands enforced the Cultivation System which was linked to famines and epidemics in the 1840s, first in Cirebon and then Central Java, as cash crops such as indigo and sugar had to be grown instead of rice.

However, the Dutch also brought modernisation to Central Java. In the 1900s, the predecessor of the modern Central Java was created, named Gouvernement of Midden-Java. Before 1905, central Java consisted of 5 gewesten (regions) namely Semarang, Rembang, Kedu, Banyumas, and Pekalongan. Surakarta was still an independent vorstenland (autonomus region) which stood alone and consisted of two regions, Surakarta and Mangkunegaran, as well as Yogyakarta. Each gewest consisted of districts. At that time, the Rembang Gewest also included Regentschap Tuban and Regentschap Bojonegoro. After the enactment of the 1905 Decentralisatie Besluit (Decentralisation Decision), the governor was given autonomy and a regional Council was formed. In addition, autonomous gemeente (municipal) was formed, namely Pekalongan, Tegal, Semarang, Salatiga, and Magelang. Since 1930, the province has been designated as an autonomous region which also has a provinciale raad (provincial council). The province consists of several residenties (residencies), which cover several regentschap (districts), and are divided into several kawedanan (districts). Central Java consists of 5 residences, namely: Pekalongan, Jepara-Rembang, Semarang, Banyumas, and Kedu.

Independence and contemporary era

On 1 March 1942, the Imperial Japanese Army landed on Java, and the following week, the Dutch colonial government surrendered unconditionally to Japan. During the Japanese rule, Java and Madura were placed under the supervision of the Japanese 16th Army. Many who lived in areas considered important to the war effort experienced torture, sex slavery, arbitrary arrest and execution, and other war crimes. Thousands of people were taken away as forced labourers (romusha) for Japanese military projects, including the Burma-Siam and Saketi-Bayah railways, and suffered or died as a result of ill-treatment and starvation. A later UN report stated that four million people died in Indonesia as a result of the Japanese occupation.[16] About 2.4 million people died in Java from famine during 1944–45.[17]

Following the surrender of Japan, Indonesia proclaimed its independence on 17 August 1945. The final stages of warfare were initiated in October when, under the terms of their surrender, the Japanese tried to re-establish the authority they relinquished to the Indonesians in towns and cities. The fiercest fighting involving the Indonesian pemuda and the Japanese was in Semarang. In a few days, British forces began to occupy the city, after which retreating Indonesian Republican forces retaliated by killing between 130 and 300 Japanese prisoners they were holding. Five hundred Japanese and 2,000 Indonesians had been killed, and the Japanese had almost captured the city six days later when British forces arrived.[18]

The province of Central Java was formalised on 15 August 1950, excluding Yogyakarta but including Surakarta.[19] There have been no significant changes in the administrative division of the province ever since. In the aftermath of the 30 September Movement in 1965, an anti-communist purge took place in Central Java, in which the army and community vigilante groups killed Communists and leftists, both actual and alleged. Others were interned in concentration camps, the most infamous of which was on the isle of Buru in Maluku, first used as a place of political exile by the Dutch. Some were executed years later, but most were released in 1979[20] In 1998, near the downfall of longtime president Suharto, anti-Chinese violence broke out in Surakarta (Solo) and surrounding areas, in which Chinese property and other buildings were burnt down. The following year, public buildings in Surakarta were burnt by supporters of Megawati Sukarnoputri after Indonesia's parliament chose Abdurrahman Wahid instead of Megawati for the presidency.

The 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake in the south and Yogyakarta devastated many buildings and caused thousands of deaths and more than 37,000 injuries.

Geography

According to the slope level of land in Central Java, 38% of the land has a slope of 0-2%, 31% has a slope of 2-15%, 19% has a slope of 15-40%, and the remaining 12% has a slope of more than 40%.

The northern coastal region of Central Java has a narrow lowland. In the Brebes area, it is 40 km wide from the coast, while in Semarang, it is only 4 km wide. This plain continues with the depression of Semarang-Rembang in the east. Mount Muria at the end of the Ice Age (around 10,000 years BC) was a separate island from Java, which eventually fused because of alluvial deposits from flowing rivers.[21] The city of Demak during the era of the Demak Sultanate was on the edge of the sea and became a thriving port. This sedimentation process is still ongoing on the coast of Semarang.[22]

In the south of the area are the Northern Cretaceous Mountains and the Kendeng Mountains, which are limestone mountains stretching from the east of Semarang from the Southwest end of Pati then east to the Lamongan and Bojonegoro in East Java.

The main range of mountains in Central Java is the North and South Serayu Mountains. The North forms a mountain chain that connects the Bogor range in West Java with the Kendeng Mountains in the east. The width of this mountain range is around 30–50 km; on the western end there is Mount Slamet, which is the highest mountain in Central Java as well as the second-highest mountain in Java, and the eastern part is the Dieng Plateau with peaks of Mount Prahu and Mount Ungaran. Between the series of North and South Serayu Mountains are separated by the Serayu Depression which stretches from Majenang in the Cilacap Regency, Purwokerto, to Wonosobo. East of this depression is the Sindoro and Sumbing volcano, and the east again (Magelang and Temanggung areas) is a continuation of depression which limits Mount Merapi and Mount Merbabu.

The Southern Serayu Mountains are part of the South Central Java Basin located in the southern part of the province. This mandala is a geoantiklin that extends from west to east along 100 kilometres and is divided into two parts separated by the Jatilawang valley, namely the western and eastern regions. The western part is formed by Mount Kabanaran (360 m) and can be described as having the same elevation as the Bandung Depression Zone in West Java or as a new structural element in Central Java. This section is separated from the Bogor Zone by the Majenang Depression.

The eastern part was built by the Ajibarang anticline (narrow anticline) which was cut by the Serayu River stream. In the east of Banyumas, the anticline developed into an anticlinorium with a width reaching 30 km in the Lukulo area (south of Banjarnegara-Midangan) or often called the Kebumen Tinggi. At the very eastern end of Mandala, the South Serayu Mountains are formed by the dome of the Kulonprogo Mountains (1022 m), which is located between Purworejo and the Progo River.

The area of the south coast of Central Java also has a narrow lowland, with a width of 10–25 km. In addition, there are South Gombong Karst Areas. Sloping hills stretch parallel to the coast, from Yogyakarta to Cilacap. East of Yogyakarta is a limestone mountain area that extends to the southern coast of East Java.

Hydrology

The rivers that empty into the Java Sea include the Bengawan Solo River, Kali Pemali, Kali Comal, and Kali Bodri, while the ones that empty into the Indian Ocean include Serayu River, Bogowonto River, Luk Ulo River and Progo River. Bengawan Solo is the longest river on the island of Java (572 km); has a spring in the Sewu Mountains (Wonogiri Regency), this river flows to the north, crosses the City of Surakarta, and finally goes to East Java and empties into the Gresik area (near Surabaya).

Among the main reservoirs (lakes) in Central Java are Gunung Rowo Lake (Pati Regency), Gajahmungkur Reservoir (Wonogiri Regency), Kedungombo Reservoir (Boyolali and Sragen Regency), Rawa Pening Lake (Semarang Regency), Cacaban Reservoir (Tegal Regency), Malahayu Reservoir (Brebes Regency), Wadaslintang Reservoir (border of Kebumen Regency and Wonosobo Regency), Gembong Reservoir (Pati Regency), Sempor Reservoir (Kebumen Regency) and Mrica Reservoir (Banjarnegara Regency).

Climate

The average temperature in Central Java is between 18–28 degrees Celsius and the relative humidity varies between 73–94%.[19] While a high level of humidity exists in most low-lying parts of the province, it drops significantly in the upper mountains.[19] The highest average annual rainfall of 3,990 mm with 195 rainy days was recorded in Salatiga.[19]

Administrative divisions

.jpg)

.jpg)

On the eve of the World War II in 1942, Central Java was subdivided into seven residencies (Dutch: residentie or plural residenties, Javanese karésiḍènan or karésidhènan) which corresponded more or less with the main regions of this area. These residencies were Banjoemas, Kedoe, Pekalongan, Semarang, and Djapara-Rembang plus the so-called Gouvernement Soerakarta and Gouvernement Jogjakarta. However, after the local elections in 1957, the role of these residencies were reduced until they finally disappeared.[23]

Today, Central Java (excluding Yogyakarta Special Region) is divided into 29 regencies (kabupaten) and six cities (kota, previously kotamadya and kota pradja), the latter being independent of any regency. The Southern (Kedu) area used to be the Surakarta Sunanate until the monarchy was un-recognised by the Indonesian government. These contemporary regencies and cities can further be subdivided into 565 districts (kecamatan). These districts are further divided into 7,804 rural communes or "villages" (desa) and 764 urban communes (kelurahan).[19]

| Name | Capital | Area (km²) | Population 2000 Census | Population 2005 Census | Population 2010 Census | Population 2015 Census |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banjarnegara Regency | Banjarnegara | 1,023.73 | 838,962 | 854,785 | 868,913 | 901,300 |

| Banyumas Regency | Purwokerto | 1,335.30 | 1,460,324 | 1,480,575 | 1,554,527 | 1,634,626 |

| Cilacap Regency | Cilacap | 2,124.47 | 1,613,964 | 1,616,922 | 1,642,107 | 1,693,937 |

| Purbalingga Regency | Purbalingga | 677.55 | 788,675 | 810,108 | 848,952 | 898,551 |

| Southwestern region | 5,161.05 | 4,701,925 | 4,762,390 | 4,914,499 | 5,128,414 | |

| Magelang City | Magelang | 16.06 | 116,800 | 124,374 | 118,227 | 120,769 |

| Kebumen Regency | Kebumen | 1,211.74 | 1,166,604 | 1,196,304 | 1,159,926 | 1,184,552 |

| Magelang Regency | Mungkid | 1,102.93 | 1,102,359 | 1,137,938 | 1,181,723 | 1,244,558 |

| Purworejo Regency | Purworejo | 1,091.49 | 704,063 | 712,851 | 695,427 | 710,275 |

| Temanggung Regency | Temanggung | 837.71 | 665,470 | 687,901 | 708,546 | 745,244 |

| Wonosobo Regency | Wonosobo | 981.41 | 739,648 | 747,984 | 754,883 | 776,847 |

| Southern (Kedu) region | 5,241.34 | 4,494,944 | 4,607,352 | 4,618,732 | 4,782,245 | |

| Surakarta (or Solo) City | Surakarta | 46.01 | 489,900 | 506,397 | 499,337 | 512,056 |

| Boyolali Regency | Boyolali | 1,008.45 | 897,207 | 923,207 | 930,531 | 963,182 |

| Karanganyar Regency | Karanganyar | 775.44 | 761,988 | 793,417 | 813,196 | 855,621 |

| Klaten Regency | Klaten | 658.22 | 1,109,486 | 1,123,484 | 1,130,047 | 1,158,400 |

| Sragen Regency | Sragen | 941.54 | 845,320 | 854,751 | 858,266 | 878,766 |

| Sukoharjo Regency | Sukoharjo | 489.12 | 780,949 | 798,574 | 824,238 | 863,528 |

| Wonogiri Regency | Wonogiri | 1,793.67 | 967,178 | 977,471 | 928,904 | 948,650 |

| Southeastern (Solo) region | 5,712.45 | 5,852,028 | 5,977,301 | 5,984,519 | 6,180,203 | |

| Pekalongan City | Pekalongan | 45.25 | 263,190 | 269,177 | 281,434 | 296,168 |

| Tegal City | Tegal | 39.68 | 236,900 | 238,676 | 239,599 | 245,995 |

| Batang Regency | Batang | 788.65 | 665,426 | 673,406 | 706,764 | 742,571 |

| Brebes Regency | Brebes | 1,902.37 | 1,711,364 | 1,751,460 | 1,733,869 | 1,780,626 |

| Pekalongan Regency | Kajen | 837.00 | 807,051 | 830,632 | 838,621 | 873,423 |

| Pemalang Regency | Pemalang | 1,118.03 | 1,271,404 | 1,329,990 | 1,261,353 | 1,288,303 |

| Tegal Regency | Slawi | 876.10 | 1,391,184 | 1,400,588 | 1,394,839 | 1,424,474 |

| Northwestern region | 5,607.08 | 6,346,519 | 6,493,929 | 6,456,479 | 6,651,560 | |

| Salatiga City | Salatiga | 57.36 | 155,244 | 165,394 | 170,332 | 183,631 |

| Semarang City | Semarang | 373.78 | 1,353,047 | 1,438,733 | 1,555,984 | 1,698,777 |

| Demak Regency | Demak | 900.12 | 984,741 | 1,008,822 | 1,055,579 | 1,116,964 |

| Grobogan Regency | Grobogan | 2,013.86 | 1,271,500 | 1,309,346 | 1,308,696 | 1,350,859 |

| Kendal Regency | Kendal | 1,118.13 | 851,504 | 907,771 | 900,313 | 941,584 |

| Semarang Regency | Ungaran | 950.21 | 834,314 | 878,278 | 930,727 | 999,817 |

| Northern region | 5,413.46 | 5,450,350 | 5,708,344 | 5,921,631 | 6,291,632 | |

| Blora Regency | Blora | 1,804.59 | 813,675 | 827,587 | 829,728 | 851,841 |

| Jepara Regency | Jepara | 1,059.25 | 980,443 | 1,041,360 | 1,097,280 | 1,186,738 |

| Kudus Regency | Kudus | 425.15 | 709,905 | 754,183 | 777,437 | 830,396 |

| Pati Regency | Pati | 1,489.19 | 1,154,506 | 1,160,546 | 1,190,993 | 1,232,214 |

| Rembang Regency | Rembang | 887.13 | 559,523 | 563,122 | 591,359 | 618,780 |

| Northeastern region | 5,665.31 | 4,218,052 | 4,346,798 | 4,486,797 | 4,719,969 | |

| Totals | 32,800.69 | 31,223,258 | 31,977,968 | 32,382,657 | 33,753,023 |

Demographics

As of the 2010 census, Central Java's population stood at 32.38 million. As of the 1990 census, the population was 28 million.[24] This reflected an increase of approximately 13.5% in 20 years. In 2019 the population was an officially estimated 34,552,500.[2]

The three biggest regencies in terms of population are: Brebes, Cilacap and Banyumas. Together they make up approximately 16% of the province's population. Major urban population centres include Greater Semarang, Greater Surakarta and the Brebes-Tegal-Slawi area in the northwest of the province.

Religion

Although the overwhelming majority of Javanese are Muslims, many also profess indigenous Javanese beliefs. Clifford Geertz, in his book about the religion of Java, made a distinction between the so-called santri Javanese and abangan Javanese.[26] He considered the former as orthodox Muslims and the latter as nominal Muslims that devote more energy to indigenous traditions.

Dutch Protestants were active in missionary activities and were rather successful. The Dutch Catholic Jesuit missionary, F.G.C. van Lith also achieved some success, especially in areas around the central-southern parts of Central Java and Yogyakarta at the beginning of the 20th century,[27] and is buried at the Jesuit necropolis at Muntilan.

Following the upheavals in 1965–66, religious identification of citizens became compulsory, and there has been a renaissance of Buddhism and Hinduism since then. As one has to choose a religion out of the five official religions in Indonesia; i.e. Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, and Buddhism, the latter two became alternatives for people who did not want to be Muslims or Christians. Confucianism is also common among Chinese Indonesians. In the post-Suharto era, it is recognised as an official religion along with the aforementioned five.

Islamic Demak Great Mosque

Islamic Demak Great Mosque Menara Kudus Mosque, one of the oldest mosques in Indonesia.

Menara Kudus Mosque, one of the oldest mosques in Indonesia. Blenduk Church, Semarang. Built in 1753, it is the oldest church in the province.

Blenduk Church, Semarang. Built in 1753, it is the oldest church in the province..jpg)

Statue of Buddha Vihara Buddhagaya Watugong, Semarang

Statue of Buddha Vihara Buddhagaya Watugong, Semarang

Ethnicity

At approximately 98%, Javanese people form the overwhelming majority of the population.[28] Central Java is known as the centre of Javanese culture. The cities of Surakarta and Yogyakarta are the centres of the Javanese royal palace that still stands today.

Significant minority ethnic groups include the Chinese Indonesians. They usually reside in urban areas, although they are also found in rural areas. In general, they primarily work in trade and services. Many speak the Javanese language with sufficient fluency as they have lived alongside the Javanese. One can feel the strong influence in Semarang and the town of Lasem in Rembang Regency, which is on the northeastern tip of Central Java. Even Lasem is nicknamed Le petit chinois or the Small Chinese City. The urban areas that are densely populated by Chinese Indonesians are called pecinan, which means "Chinatown". Additionally, in several major cities, the Arab-Indonesian community can also be found. Similar to the Chinese community, they are usually engaged in trade and services.

In areas bordering the province of West Java, there are Sundanese people and Sundanese culture, especially in the Cilacap, Brebes, and Banyumas regions. Sundanese toponyms are common in these regions such as Dayeuhluhur in Cilacap, Ciputih and Citimbang in Brebes and even Cilongok as far away in Banyumas.[29] In the interior of Blora, which borders East Java, there is an isolated Samin community, the case of which is almost the same as the Baduy people in Banten.

Language

Although Indonesian is the official language, people mostly speak Javanese as their daily language. The Solo-Jogja dialect or the Mataram dialect is considered as the standard Javanese Language.

Additionally, there are a number of Javanese dialects but in general, it consists of two, namely kulonan and timuran. The former is spoken in the western part of Central Java, consisting of the Banyumasan dialects and Tegal dialects (also called Basa Ngapak). They are quite different in pronunciation from the standard Javanese. The latter dialect is spoken in the eastern part of the province, including the Mataram dialect (Solo-Jogja), Semarang dialect, and the Pati dialect. Between the borders of the two dialects, Javanese is spoken with a mixture of both dialects; these areas are Pekalongan and the Kedu Plain, which composes Magelang and Temanggung.

Past the western region in Central Java province is the Kingdom of Sunda region, so there are residents using Sundanese language, but this language is shrinking because of the lack of support from the government. In Sundanese-populated areas, namely in the southern Brebes Regency, and the west region Cilacap Regency, around Dayeuhluhur sub-district, Sundanese is still commonly spoken.[30]

Culture

Central Java is considered to be the heart of the Javanese culture. The ideal conduct and moral of the courts (such as politeness, nobility and grace) has a tremendous influence on the people. They are known as soft-spoken, very polite, extremely class-conscious, apathetic, down-to-earth, etc. These stereotypes form what most non-Javanese see as the "Javanese Culture", when in fact, not all Javanese behave in such manner as most Javanese are far from the court culture.[9]

Mapping the Javanese cultures

The Javanese cultural area can be divided into three distinct main regions: Western, Central, and Eastern Javanese culture or in their Javanese names as Ngapak, Kejawèn and Arèk. The boundaries of these cultural regions coincide with the isoglosses of the Javanese dialects. Cultural areas west of Dieng Plateau and Pekalongan Regency are considered Ngapak whereas the border of the eastern cultural areas or Arèk lies in East Java. Consequently, culturally, Central Java consists of two cultures, while the Central Javanese Culture proper is not entirely confined to Central Java.[9]

Creative arts

Architecture

The architecture of Central Java is characterised by the juxtaposition of the old and the new and a wide variety of architectural styles, the legacy of many successive influences from the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, China, and Europe. In particular, northern coastal cities such as Semarang, Tegal, and Pekalongan can boast European colonial architecture. The European and Chinese influence can be seen in Semarang's temple of Sam Poo Kong dedicated to Zheng He and the Domed Church built in 1753. The latter is the second-oldest church in Java and the oldest in Central Java. In the former capital of Surakarta, there are also several European architectures.

Central Java also has some notable religious buildings. The Borobudur and the Prambanan temple complexes are among the largest Buddhist and Hindu structures in the world. In general, a characteristic Javanese mosque does not have a dome as its roof but a Meru-like roof which is reminiscent of a Hindu or Buddhist temple. The tower of the famous Mosque of Kudus resembles a Hindu-Javanese or Balinese temple more than a traditional Middle Eastern mosque.

Batik

Central Java is famous and well known for its exquisite batik, a generic wax-resist dyeing technique used on textiles. There are different styles of batik motifs. A centre of batik production is in Pekalongan. Other centres include Surakarta and Yogyakarta. Batik in Pekalongan style, which represent gaya pesisir (or coastal style), is different from the one in Surakarta and Yogyakarta that represent batik from the heartland of Java (gaya kejawèn).[31]

Dance

One can even see the court influences in the art forms. The dances of the courts of Java are usually slow and graceful with no excessive gestures. The people followed this approach, and as a result, slow-paced and graceful movements can even be found in folk dances throughout Central Java, though with some exceptions. One can enjoy the beauty of Central Javanese dances in "Kamajaya-Kamaratih" or "Karonsih", usually performed in a traditional Javanese wedding.

Theatre

There are several kinds of Central Javanese theatre and performing arts. The most well-known is the Javanese wayang theatre, which has several types. These are wayang kulit, wayang klitik, wayang bèbèr, wayang golèk, and wayang wong. Wayang kulit are shadow puppets theatre with leather puppets. The stories are loosely based on Mahabharata and Ramayana cycles. Wayang klitik are puppets theatre with flat wooden puppets. The stories are based on Panji (king) stories. Panji was a native Javanese princes who embarked a 'journeys of desire'.[32] Wayang bèbèr is scroll theatre, and it involves "performing" scenes of a story elaborately drawn and painted on rolled sheets. Wayang golèk consists of three-dimensional wooden puppets. The narrative can be based on anything, but usually are drawn from Islamic heroic ones. Finally, wayang wong is wayang theatre involving live figures, actors who are performing a play. The narrative, however, must be based on Mahabharata or Ramayana.

In addition to wayang, there is another form of theatre called ketoprak. It is a staged play by actors accompanied by Javanese gamelan. The narrative is free but cannot be based on Mahabharata or Ramayana.

Music

Central Javanese music is almost synonymous with gamelan. It is a musical ensemble typically featuring a variety of instruments such as metallophones, xylophones, drums, gongs, bamboo flutes, bowed and plucked strings. Vocalists may also be included. The term refers more to the set of instruments than the players of those instruments. A gamelan as a set of instruments is a distinct entity, built and tuned to stay together. Instruments from different gamelan are not interchangeable. However, gamelan is not typically Central Javanese as it is also known elsewhere.

Contemporary Javanese pop music is called campursari. It is a fusion between gamelan and Western instruments, much like kroncong. Usually, the lyrics are in Javanese, though not always. One notable singer is Didi Kempot, born in Sragen, north of Surakarta. He mostly sings in Javanese.

Literature

It can be argued that Javanese literature started in Central Java. The oldest-known literary work in the Javanese language is the inscription of Sivagrha from Kedu Plain. This inscription, which is from 856 AD, is written as a kakawin or Javanese poetry with Indian metres.[33] The oldest of narrative poems, Kakawin Ramayana, which tells the well-known story of Ramayana, is believed to have come from Central Java. It can be safely assumed that this kakawin were written in the central Java region in the 9th century.[34]

After the shift of Javanese power to eastern Java, it had been quiet from Central Java for several centuries concerning Javanese literature until the 16th century. At this time, the centre of power was shifted back to Central Java. The oldest work written in modern Javanese language concerning Islam is the so-called "Book of Bonang" or also "The Admonitions of Seh Bari". This work is extant in just one manuscript, now kept in the University of Leiden as codex Orientalis 1928. It is assumed that this manuscript originates from Tuban, in eastern Java and was taken to the Netherlands after 1598.[35] However, this work is attributed to Sunan Bonang, one of the nine Javanese saints who spread Islam in Java and Sunan Bonang came from Bonang, a place in Demak Regency, Central Java. It can be argued that this work marked the beginning of Islamic literature in the region.

However, the pinnacle of Central Javanese literature was created at the courts of the kings of Mataram in Kartasura and later in Surakarta and Yogyakarta that are mostly attributed to the Yasadipura family. The most famous member of this family is Rangga Warsita who lived in the 19th century. He is the best-known of all Javanese writers and also one of the most prolific. He is also known as bujangga panutup or "the last court poet".

Following independence, the Javanese language as a medium was pushed to the background. Still, one of the greatest contemporary Indonesian authors, Pramoedya Ananta Toer was born in 1925 in Blora. He was an author of novels, short stories, essays, polemics, and histories of his homeland and its people. A well-regarded writer in the West, his outspoken and often politically-charged writings faced censorship at home. He faced extrajudicial punishment for opposing the policies of both President Sukarno and Suharto. During imprisonment and house arrest, he became a cause célèbre for advocates of freedom of expression and human rights. In his works, he writes much about life and social problems in Java.

Cuisine

Rice is the staple food of Central Java. In addition to rice, dried cassava, known locally as gaplèk, also serve as a staple food. Javanese food tends to taste sweet. Cooked and stewed vegetables, usually in coconut milk (santen in Javanese) are prevalent. Raw vegetable, which is popular in West Java, is less prevalent in Central Java.

Saltwater fish, both fresh and dried are common, especially among coastal areas. Freshwater fish is not popular in Central Java, unlike in West Java, except perhaps for catfish known locally as lélé. It is usually fried and served with chilli condiment (sambal) and raw vegetables.

Chicken, mutton and beef are common meat. Certain parts of the population also eat dog meat, known by its euphemism daging jamu (literally "traditional medicine meat").

Tofu and tempe serve as the standard replacement to fish and meat. Famous dishes in Central Java include gudeg (sweet stew of jackfruit) and sayur lodeh (vegetables cooked in coconut milk).

Besides the aforementioned tofu, there is a strong Chinese influence in numerous dishes. Some examples of Sino-Javanese food include noodles, bakso (meatballs), lumpia, soto etc. The widespread use of sweet soybeans sauce (kecap manis) in the Javanese cuisine can also be attributed to the Chinese influence.

Nasi Gudeg, mostly found in Yogyakarta and Surakarta

Nasi Gudeg, mostly found in Yogyakarta and Surakarta Nasi Liwet Solo

Nasi Liwet Solo- Soto Kudus

Lumpia Semarang

Lumpia Semarang Tempe Goreng

Tempe Goreng

Transportation

Central Java is connected to the Trans-Java Toll Road which currently runs from Merak in Banten to Probolinggo (planned: Banyuwangi), East-Java. Within the province the toll road starts at Brebes, continuing via Semarang and Surakarta until east of Sragen. Along the north coast east of Semarang, the North Coast Road (Jalur Pantai Utara or Jalur Pantura) is the main road. Losari, the Central Javanese gate at the western border on the northern coast, could be reached from Jakarta in 4 hours drive. On the southern coast, there is also a national way which run from Kroya at the Sundanese-Javanese border, through Yogyakarta to Surakarta and then to Surabaya via Kertosono in East Java. There is furthermore a direct connection from Tegal to Purwokerto and from Semarang to Yogyakarta and Surakarta.

Central Java was the province that first introduced a railway line in Indonesia. The very first line began in 1873 between Semarang and Yogyakarta by a private company,[36] but this route is now no longer used. Today there are five lines in Central Java: the northern line which runs from Jakarta via Semarang to Surabaya. Then there is the southern line from Kroya through Yogyakarta and Surakarta to Surabaya. There is also a train service between Semarang and Surakarta and a service between Kroya and Cirebon. At last there is a route between Surakarta and Wonogiri. The line between Kutoarjo and Surakarta, the line from Cirebon to Kroya up to Purwokerto and the entire north coast line (since 2014) are double-track,[37] while second tracks from Surakarta to Kertosono (towards Surabaya) and Purwokerto-Kroya-Kutoarjo are under construction of which the latter will be finished in 2019 .[38] Other lines are single-track.

On the northern coast Central Java is served by 8 harbours. The main port is Tanjung Mas in Semarang, other harbours are located in Brebes, Tegal, Pekalongan, Batang, Jepara, Juwana and Rembang. The southern coast is mainly served by the port Tanjung Intan in Cilacap.[39]

Finally on mainland Central Java there are three commercial airports. There is one additional commercial airport on the Karimunjawa isles. The airports on the mainland are: Adisumarmo International Airport in Surakarta, Achmad Yani Airport in Semarang and Tunggul Wulung Airport in Cilacap. Karimunjawa is served by Dewadaru Airport.

Ahmad Yani International Airport in Semarang

Ahmad Yani International Airport in Semarang- Trains in Kroya Station, Cilacap Regency

Becak lining up in Surakarta street

Becak lining up in Surakarta street Port of Karimun Jawa

Port of Karimun Jawa

Economy

GDP in the province of Central Java was estimated to be around $US 98 billion in 2010, with a per capita income of around $US 3,300. Economic growth in the province is quite rapid and GDP is forecast to reach $US 180 billion by 2015. The poverty rate of its people is 13% and will be decreased below 6%.[40]

Agriculture

Much of Central Java is a fertile agricultural region. The primary food crop is wet rice. An elaborate irrigation network of canals, dams, aqueducts, and reservoirs has greatly contributed to Central Java's the rice-growing capacity over the centuries. In 2001, productivity of rice was 5,022 kilograms/ha, mostly provided from irrigated paddy field (± 98%). Klaten Regency had the highest productivity with 5525 kilograms/ha.[41]

Other crops, also mostly grown in lowland areas on small peasant landholdings, are corn (maize), cassava, peanuts (groundnuts), soybeans, and sweet potatoes. Terraced hillslopes and irrigated paddy fields are familiar features of the landscape. Kapok, sesame, vegetables, bananas, mangoes, durian fruits, citrus fruits, and vegetable oils are produced for local consumption. Tea, coffee, tobacco, rubber, sugarcane and kapok; and coconuts are exported. Several of these cash crops at a time are usually grown on large family estates. Livestock, especially water buffalo, is raised primarily for use as draft animals. Salted and dried fish are imported.[41][42]

Education

Central Java is home to such notable state universities, as Diponegoro University, Semarang State University, and Walisongo Islamic University (Universitas Islam Negeri Walisongo) in Semarang; Sebelas Maret University in Surakarta; and Jenderal Soedirman University in Purwokerto.

The Military Academy (Akademi Militer) is located in Magelang Regency while the Police Academy (Akademi Kepolisian) is located in Semarang. Furthermore, in Surakarta the Surakarta Institute of Indonesian Arts (ISI Surakarta) is located. In addition to these, Central Java has hundreds of other private higher educations, including religious institutions.

For foreign students requiring language training Salatiga has been a location for generations of students attending courses.

Tourism

There are several tourism sites in Central Java. Semarang itself has many old buildings: Puri Maerokoco and the Indonesian Record Museum are located in this city.

Borobudur, which is one of the UNESCO World Cultural Heritage sites of Indonesia, is also located in this province, in the Magelang Regency. Candi Mendut and Candi Pawon can also be found near the Borobudur temple complex.

Candi Prambanan, on the border of Klaten regency and Yogyakarta is the biggest complex of Hindu temples. It is also a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site. There are several temples in the region around the Dieng Plateau. These date from before the era of the ancient Mataram.

The Palace of the Sunan (Keraton Kasunanan) and Pura Mangkunegaran, are located in Surakarta, while the Grojogan Sewu waterfall is located in Karanganyar Regency. Several Majapahit temples and Sangiran museum are also located in Central Java.

Coat of arms and symbols

The motto of Central Java is Prasetya Ulah Sakti Bhakti Praja. This is a Javanese phrase meaning "A vow of devotion with all might to the country". The coat of arms of Central Java depicts a legendary flask, Kundi Amerta or Cupu Manik, formed in a pentagon representing Pancasila. In the centre of the emblem stands a sharp bamboo spike (representing the fight for independence, and it has 8 sections which represent Indonesia's month of Independence) with a golden five-pointed star (representing faith in God), superimposed on the black profile of a candi (temple) with seven stupas, while the middle stupa is the biggest. This candi is reminiscent of the Borobudur. Under the candi wavy outlines of waters are visible. Behind the candi two golden mountain tops are visible.

These twin mountains represents the unity between the people and their government. The emblem shows a green sky above the candi. Above, the shield is adorned with a red and white ribbon, the colours of the Indonesian flag. Lining the left and right sides of the shield are respectively stalk of rice (17 of them, representing Indonesia's day of Independence) and cotton flowers (5 of them, each one is 4-petaled, representing Indonesia's year of Independence). At the bottom, the shield is adorned with a golden red ribbon. On the ribbon the name "Central Java" (Jawa Tengah) is inscribed in black. The floral symbol of the province is the Michelia alba, while the provincial fauna is Oriolus chinensis.

Further reading

- Tourist (printed information)

- Backshall, S. et all (1999) Indonesia, The rough guide London ISBN 1-85828-429-5. Central Java – pp. 153–231

- Cribb, Robert (2000) Historical Atlas of Indonesia London: Curzon Press

- Dalton. B. (1980s) Indonesia Handbook various editions – Central Java.

- Geertz, C. (1960) The Religion of Java University Of Chicago Press 1976 paperback: ISBN 0-226-28510-3

- Hatley, Ron et al. (1984) Other Javas: away from the kraton Clayton: Monash University

- Vaisutis. Justine et al. (2007) Indonesia Eighth edition. Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd, Footscray, Victoria ISBN 978-1-74104-435-5

References

- Museum Kepresidenan (12 September 2018). "Sejarah Wilayah Indonesia". Ministry of Education and Culture. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2019.

- "Kewarganegaraan, Suku Bangsa, Agama, Bahasa, 2010 (PDF)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- "Indonesia". Badan Pusat Statistik. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Cited in Whitten, T.; Soeriaatmadja, R.E.; Suraya, A.A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. pp. 309–312:

Pope, G. (1988). "Recent advances in far eastern paleoanthropology". Annual Review of Anthropology. 17: 43–77. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.17.100188.000355.

Pope, G. (15 August 1983). "Evidence on the Age of the Asian Hominidae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 80 (16): 4988–4992. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.16.4988. PMC 384173. PMID 6410399.

de Vos, J.P.; Sondaar, P.Y. (9 December 1994). "Dating hominid sites in Indonesia" (PDF). Science Magazine. 266 (16): 4988–4992. doi:10.1126/science.7992059. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 14 March 2019. - Raffles, Thomas E. (1965) "The History of Java". Oxford University Press, p. 32.

- Raffles, Thomas E. (1965) "The History of Java". Oxford University Press, p. 2.

- Kapur, Kamlesh (2010). History of Ancient India. Sterling Publishers. ISBN 978-8120749108. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- Hatley, R., Schiller, J., Lucas, A., Martin-Schiller, B., (1984). "Mapping cultural regions of Java" in: Other Javas away from the kraton. pp. 1–32.

- J. Oliver Thomson (2013). History of Ancient Geography. Cambridge University Press. pp. 316–317. ISBN 978-1-107-68992-3.

- Denys Lombard (1990). The Javanese Crossroads: Essay of global history.

- Mills, J.V.G. (1970). Ying-yai Sheng-lan: The Overall Survey of the Ocean Shores [1433]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Yule, Sir Henry (1913). Cathay and the way thither: being a collection of medieval notices of China vol. II. London: The Hakluyt Society.

- "Java man (extinct hominid) – Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- Robert Cribb, Historical Atlas of Indonesia (2000:30)

- Cited in: Dower, John W. War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (1986; Pantheon; ISBN 0-394-75172-8).

- Van der Eng, Pierre (2008) 'Food Supply in Java during War and Decolonisation, 1940–1950.' MPRA Paper No. 8852. pp. 35–38. Archived 3 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Ricklefs 1991, p. 216.

- Archived June 29, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Robert Cribb, Historical Atlas of Indonesia (2000:170–171).

- Sunarto (2006). "Geomorphological Development of the Muria Palaeostrait in Relation to the Morphodynamics of the Wulan Delta, Central Java". Indonesian Journal of Geography.

- hermes (4 November 2018). "Semarang is sinking – 'all has become sea' for its tiny neighbour". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 4 November 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- Robert Cribb, Historical Atlas of Indonesia (2000:165)

- Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia (1997:1249)

- "Population by Region and Religion in Indonesia". BPS. 2010. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- Clifford Geertz, The Religion of Java (1976:121–131), paperback edition

- "Van Lith dan Muntilan "Bethlehem van Java"". Kompas (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 19 June 2006.

- Indonesia's Population: Ethnicity and Religion in a Changing Political Landscape. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 2003.

- Sundanese toponyms often begins with the morpheme ci-, which means "river" or "water" "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Dayeuh is a Sundanese word which means region, q.v. F.S. Eringa Soendaas-Nederlands woordenboek (1984)

- Permana, Merdeka. 2010 "Sunda Lelea yang Terkatung-katung": Pikiran Rakyat

- Ron Hatley, Mapping the Javanese cultures (1984:10–11)

- Vickers, Adrian (2005). Journeys of Desire: A Study of the Balinese Text Malat. Leiden: KITLV. ISBN 9789067181372.

- De Casparis, "A Metrical Old Javanese Inscription Dated 865 A.D." in Prasasti Indonesia II (1956:280–330)

- Zoetmulder, Petrus Josephus (1974). Kalangwan: a survey of old Javanese literature. Martinus Nijhoff. p. 231.

- Drewes, G.W.J. (1969). The Admonitions of Seh Bari. Brill. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-90-04-24793-2.

- Robert Cribb, Historical Atlas of Indonesia (2000:140)

- "Double track for Trans-Java line to be operational in March". Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Pembangunan rel ganda Purwokerto-Kroya mencapai 97,73 persen" [Construction second track Purokerto-Kroya reaches 97.73%] (in Indonesian). 15 January 2019. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Perhubungan" (in Malay). Archived from the original on 13 April 2007.

- SAID : ANGKA KEMISKINAN DI JAWA TENGAH HARUS DITURUNKAN Archived 6 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine.siaran nasional.com (diakses 20 februari 2018)

- Archived March 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Central Java. |

- Official website (in Indonesian)

- Media Online