Human trafficking in Texas

Human trafficking in Texas is the illegal trade of human beings as it occurs in the state of Texas. It is a modern-day form of slavery and usually involves commercial sexual exploitation or forced labor, both domestic and agricultural.

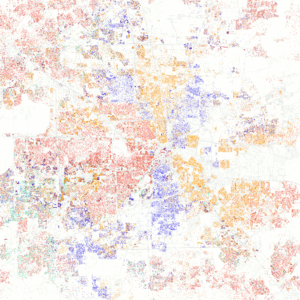

Human trafficking is particularly relevant to Texas because of its close proximity to the U.S.–Mexican border, one of the most-crossed international borders in the world,[1] and its extremely diverse population, especially in Houston.[2] According to the Department of Health and Human Services, of the more than 50,000 people annually trafficked from foreign countries into the United States, a quarter enter the country through Texas.[3] Additionally, at any given time, Texas contains around 25% of the trafficked persons in the United States, and almost a third of the calls to the National Human Trafficking Hotline are from Texas.[3] Texas is also a huge transit site for domestic trafficking, with around twenty percent of domestic trafficking victims traveling through Texas.[3]

The Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA) defines sex trafficking as the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act, in which the commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not attained 18 years of age.[4] The National Human Trafficking Resource Center reported receiving 1,731 calls and emails in 2015 about human trafficking in Texas.[5]

Overview

See also: Human trafficking and Human trafficking in the United States

Definition

According to the U.N. Protocol to Prevent Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, human trafficking is "…the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs…".[6] The transportation of children for exploitative purposes is also classified as human trafficking.[6]

Human smuggling and human trafficking

Human smuggling is the movement of people from one country into another in exchange for monetary compensation.[7] In this situation, both the smuggler and the person being smuggled are willingly participating in illegal border entry without proper documentation and are thus committing a crime against the country of entry.[7] Both can be convicted of felony.[7] However, human traffickers are committing crimes against the trafficked persons and use deception or threats to force the person into exploitative labor agreements.[7] Only the trafficker can be convicted of felony; the trafficked person is not a criminal, but a victim.[7] While human trafficking may, in some cases, involve smuggling the person across international borders, this is done against the will of the trafficked person through the use of threat, force, fraud, or any other kind of deception.[7] It is important to acknowledge that, while both human smuggling and human trafficking are prevalent in Texas, they are treated as two completely different criminal acts by the law.[7]

Current statistics

According to a 2011 study conducted by the Dallas Women's Foundation on the status of human trafficking in Dallas, Texas, "740 girls under the age of 18 were documented being marketed for sex during a 30-day period. 712 of these girls were being marketed through Internet classified web sites; 28 were being marketed through escort services."[8] According to the National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC), in 2014, there were 452 reported cases of human trafficking and 1,876 calls made to the center.[9] Texas ranked second in the nation for number of tips to the NHTRC, with 2,236 calls, emails, or tip forms received by the center.[10] Between January 1, 2007 and January 9, 2014, there were 709 human trafficking- related incidents and 176 suspects were arrested during this period.[10] The Schapiro Group reports that, on a typical weekend night in Texas, 188 girls under the age of 18 are commercially sexually exploited through internet sex ads.[2]

A 2016 study by the Institute on Domestic and Sexual Violence at the University of Texas at Austin estimated the prevalence of labor trafficking and minor sex trafficking victim prevalence to be 313,000 in the state of Texas.[11] This study also estimated the industry to cost Texas at $6.6 billion.[11]

Types of trafficking

Forced labor

Labor trafficking plays a large role in Texas' economy, but still fails to receive sufficient attention in anti-trafficking legislation.[3] The number of instances of labor trafficking has increased with the growing globalization of trade and the accompanying desire to increase profits by minimizing labor costs.[12] Because internationally trafficked forced laborers are not protected by Texas state law, employers are not bound to compliance with baseline occupational standards, such as minimum wage and benefits.[13]

Trafficked persons are employed in a variety of industries, including restaurants, farms, hotel housekeeping, and manufacturing plants, and are given minimal compensation for employment.[14] Labor trafficking schemes are perpetrated by both smaller family operations and by large organized crime, and these perpetrators are often from the same country of origin as their victims.[15] In many cases, forced laborers are international migrants promised work and a visa, but upon arrival are forced to pay off smuggling debts through employment.[15]

Domestic servitude

Domestic servitude is the forced employment of someone as a maid or nanny, and victims are often migrant women who come from low-wage communities in their home countries.[14] Perpetrators are usually married couples from the same country of origin as the trafficked person,[15] and are usually not involved in organized criminal networks,[13] making it more difficult to identify instances of this type of trafficking. Perpetrators of domestic servitude are often well-respected members of their communities and lead otherwise normal lives.[13] Countries and areas with large middle-class and upper middle-class populations, such as Texas, are commonly the destinations of this type of trafficking.[14]

It is important to make the distinction between legally employed domestic workers and illegally employed domestic servants. While legally employed domestic house workers are fairly compensated for their work in accordance with national wage laws, domestic servants are typically forced to work extremely long hours for little to no monetary compensation, and psychological and physical means are employed to limit their mobility and freedom.[14] In addition, deportation threats are often used to discourage internationally trafficked persons from seeking help.[14]

Food services

Texas serves as a hub to traffic victims to Chinese restaurants to other parts of the United States. In one case, the Hong Li Enterprise and Texas Job Agency out of Houston charged workers $300-$630 a person for transportation, job placement and housing fees. In 2014, authorities arrested the owners of Asian Garden Chinese Restaurant as part of a major human trafficking ring in San Marcos.[16]

Forced prostitution

Forced prostitution affects primarily women and children, who come from both domestic and international sources. Internationally trafficked persons are often from developing countries with inadequate legal frameworks to protect citizens from sex trafficking.[14][15] Perpetrators are typically large- scale crime rings and are often involved in other illegal activities.[13] One common scheme used to lure victims from poor, rural areas exploits romance as a coercion method, where pimps conceal their identities as traffickers and deceive women into thinking they are being courted.[15] They are then transported to America under the impression that they will be marrying their trafficker, at which point they are then forced into prostitution.[15] Clients are often of the same ethnicity as the forced prostitutes, and are usually targeted through fliers or word of mouth in their own ethnic communities.[15]

In Texas, many brothels are run behind the front of a legal business, such as restaurants or massage parlors, and sex trafficking victims are often forced to work in these businesses as well. For example, in 2005, Maximino "El Chimino" Mondragon was convicted of running a Houston sex ring involving around 120 women trafficked illegally from Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua. These women were forced to work in Mondragon's cantina-front brothel as both waitresses and prostitutes, and were forced to use sexual favors to entice men to purchase drinks from the bar.[17]

Residential brothels, often housed in apartment complexes, are another venue employed by sex traffickers for prostitution. Because residential brothels make forced prostitution schemes easier to conceal, and because they permit less- inhibited movement of traffickers and victims between cities, they are becoming increasingly more prevalent.[15] Services offering delivery of sex trafficking victims to hotels, clients' homes, or other locations, are also becoming increasingly popular for many of the same reasons.[15]

Demographics of trafficked persons

General characteristics

Most trafficked persons in Texas, whether domestic or international, come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.[15] Some internationally trafficked persons are lured by false promises of education and a better life in the United States.[18] In other situations, what begins as a smuggling arrangement can turn into a case of human trafficking. In these schemes, smuggled persons are forced into coercive labor agreements upon arrival in order to pay off smuggling debts, and additional, "unforeseen" smuggling costs incurred during transportation are often added to the total.[18] Many of these exploitative labor agreements deduct money for food and shelter, and smuggled persons are usually kept in the dark as to how much they still owe the smuggler.[18] This has become increasingly more common as increased border security has pushed up the cost of smuggling into the U.S.[15] International trafficking victims are controlled with threats of deportation, confiscation of identification and travel documents, and even threats of physical harm to other family members back at home.[19] Other reasons for trafficked persons' hesitation in reporting criminal activity to the authorities include their fear of incurring felony charges for their illegal immigration status,[19] their distrust of the criminal justice system, language barriers, and an unawareness of their own victimization, which often occurs with trafficked minors.[20]

Intense anti-immigrant hostility from some sectors of the U.S. population and increasingly stringent border control policies in the past couple decades have also fed the growing human trafficking trade.[19] These factors have severely restricted the job options of undocumented immigrants to the least desirable jobs, many of which can transform into exploitative forced labor contracts and forced prostitution.[19]

Region of origin

Latin America

A third of the 50,000 people annually trafficked into the United States are from Latin America, and the majority of these people enter the US through the Mexico–Texan border.[19] This extremely porous border has historically been the site of one of the most protracted labor migrations in the world, and currently holds the title as North America's largest transit site for young children exploited in labor and sex trafficking.[3][18][19] Mexico serves as a source, destination, and transit country for trafficked persons from countries all over Latin America, including Brazil and Guatemala, and 100,000 women are transported across Latin American borders every year for employment as prostitutes.[19]

Structural causes in Mexico

Mexico's social instability has helped feed its burgeoning human trafficking trade with the U.S.[19] Between 2000 and 2002, approximately 135,000 children in Mexico were kidnapped, presumably for exploitation in prostitution, pornography, or illegal adoption trafficking.[19] It is estimated that there are around 16,000 children currently engaged in prostitution in Mexico.[19]

While sex work is not completely legal in Mexico, most cities do have Zonas de Tolerancia (areas where prostitution is allowed), and this has made Mexico a huge destination for sex tourism and one of the world's largest hubs for sex trafficking. The high profitability of prostitution in Mexico has inevitably led to the forcible exploitation of many girls as sex workers.[1] Mexico is currently on the Tier 2 Watch List of the State Department's annual Trafficking in Persons Report, a designation given to countries that do not meet the minimum standards of the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2003 (TVPRA), but which are still making efforts to comply with these guidelines.[20] One of the reasons given for this designation is Mexico's thriving child sex trafficking industry- there are 16,000 to 20,000 Mexican and Central American children who are currently being trafficked for sex in Mexico.[20] Another significant reason is Mexico's lack of a commitment to anti-trafficking efforts on a national level and the complete absence of a national anti-trafficking law.[20] Governmental ineffectiveness and rampant corruption has corroded trust in the Mexican government, which is evident in the declining rate of crime reporting in border regions of Mexico.[20]

Running away from home is one of the largest risk factors for eventual exploitation and trafficking of both children and adults.[1] There are a variety of reasons for Mexico's large number of runaways, including domestic violence (whether directed at them or at other family members), parental substance abuse, other family dysfunctions such as extreme poverty, or constant sexual abuse perpetrated by people at home or in the community, all of which make the home an unpleasant living environment.[1][19] A large consequence of running away is the halting of formal education, leaving runaways untrained for most jobs other than sex work.[1] Because these children lack any social support from society, the government, or family, they are especially vulnerable to exploitation by pimps and traffickers, who conceal their true intentions by providing for these runaways and pretending to care for them.[1] This lack of social or medical support also leads to the development of drug addictions among some runaways as a coping mechanism, with many pimps and traffickers taking advantage of this addiction.[1]

Many of the trafficked persons from Mexico who eventually end up in the U.S. are teen mothers.[1] Despite the fact that many of these pregnancies are a result of rape from members of their community or family, they are often thrown out of their homes and receive little to no social support from society or the government.[1] As a consequence, these girls are also not able to complete their education, giving them few options for employment.[1] Because they usually receive very little or no financial support from the fathers, many of whom desert them following pregnancy, and because they typically have incomplete educations, these girls often have no other option but to turn to prostitution in order to provide for both themselves and their children.[1] In some situations, traffickers or pimps will provide assistance to pregnant girls, which they later leverage to coerce them into sex work.[1] In other situations, traffickers use the child to coerce mothers into sex work, either by threatening abuse towards the child or withholding the child from its mother.[1]

One of the major factors leading to the creation of Mexico's extensive trafficking industry (and its consequent overflow into the Texas) was the widespread sexual assaults of indigenous women during the Central American civil wars of the 1980s.[19] Thousands of poor women, mainly from rural areas, were raped during the El Salvadorean and Nicaraguan civil wars by army personnel and civil police.[19] They were subsequently shunned by their communities as tainted and ruined, leading many of them to migrate North to escape family shame and war-time conditions.[19]

"Coyotes"

"Coyote" is the colloquial term used to refer to migrant smugglers along the Mexico–United States border.[12] In the past, the coyote–migrant relationship ended once the smuggled person reached the United States.[6] However, in recent years, it has become increasingly more common for coyotes to coerce migrants into exploitative labor agreements upon reaching the U.S.[6] These labor agreements involve forced agricultural labor and forced prostitution, working conditions these migrants would never have consented to had they been previously informed.[6] Coyotes are able to use the threat of unpaid debt to coerce migrants into these agreements. The rising costs of smuggling, a result of increased border security, has made it easier for migrants to become indebted to smugglers.[6] Additionally, the expansion of the role of the coyote into transportation of the migrants to a final destination upon arrival in the U.S., where previously, the smuggler's job solely covered transportation across the border, also incurs additional expenses that the migrant must pay, and increases the likelihood of their being exploited and trafficked by the coyote as forced laborers.[6]

Smugglers sometimes offer reduced fees to women and children migrants, but then sexually assault or rape them as "payment".[19] Human traffickers masquerading as coyotes often use false promises of guaranteed jobs to lure migrants, and will sometimes kidnap women and children along the journey, either for ransom from their families, or to be sold in the US into servitude or prostitution.[19] Unaccompanied children, including runaways, are sometimes sold into prostitution by the trafficker, and their families are falsely led to believe that they died during transit.[19]

East Asia

East Asia is one of the main regions of origin for many trafficking victims coerced into prostitution.[21] Constituent regions include Northeast Asia (China, Japan, North and South Korea, Mongolia, and Russia) and Southeast Asia (Burma, Thailand, Laos, Nepal, Philippines, Cambodia, India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka), with the majority of trafficked persons coming from Southeast Asia and South Korea.[22] The majority of East Asian countries are categorized as Tier 2, Tier 2 Watch List, or Tier 3 of the State Department's annual Trafficking in Persons Report.[21]

East Asia is a large migrant exporter, with the number of people leaving the region increasing by 30% between 1995 and 2005.[22] While most of these people leave through legal means, this huge exodus of people has also facilitated the evolution of large transnational human trafficking networks, and the United States is a large destination for many of these trafficked persons.[22] These large transnational crime networks traffic primarily women and children, and cycle them through prostitution circuits with stops in large metropolitan areas around the country, usually only for several weeks at a time.[23] Texas is an attractive stop for these circuits due to its sizable Asian population, which makes it easier for Asian trafficking victims to blend in.[24] Texas sex trafficking operations involving Asian women and children typically operate out of massage parlors and hostess clubs, and are usually located in predominantly Asian areas with primarily Asian customer bases.[24]

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the world's largest hub for the trade in women and children, and accounts for a third of the world's human trafficking trade.[25] Southeast Asia is also the largest regional source for trafficking into the United States, with 60% of all internationally sourced trafficked persons in the U.S. originating from Southeast Asia.[25] Source countries include Burma, Thailand, Laos, Nepal, Philippines, Cambodia, India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka.[25] The majority of trafficked persons from Southeast Asia are involved in forced prostitution, but there are some isolated cases of forced domestic labor.[25] The main social determinant for sex trafficking in Southeast Asia is poverty, with many women promised an opportunity to earn money for their families.[25] In addition, poverty is also linked with other social determinants, such as lack of formal education and low class status.[25] Another large social determinant for sex trafficking from Southeast Asia is the low value placed in women and girls.[25] This is a result of the custom for women to change loyalties to their husbands' families following marriage and the financial burden of marriage dowries, which is placed on the bride's family and which is especially high in countries like India.[21]

Locations

El Paso

The strong economic and social ties between El Paso and Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua make El Paso one of the most popular destinations for trafficking from Mexico.[1] While Ciudad Juarez has already destroyed its Zona de Tolerancia in an effort to create a new image for the city, its plan to move sex work outside the city limit was never fully instituted.[1] As a consequence, most of Ciudad Juarez's sex workers are still located in the Zona Centro, which is the commercial center of the city's downtown area.[1] The estimated 6,000 sex workers in Ciudad Juarez operate out of a variety of businesses, including cantinas, nightclubs, bars, and the streets, and Ciudad Juarez is a huge destination for sex tourism from the United States.[1] Because of El Paso's strong links with Ciudad Juarez, this thriving sex trade and the sex trafficking trade that has developed with it has spilled into El Paso, making it one of Texas' largest entry points for trafficked persons from Mexico.[1]

Houston

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, Houston is one of the largest hubs for human trafficking in the nation[26] and the largest hub in Texas.[27] Houston has over 200 active brothels, with two new openings each month.[28]

The main factors that contribute to high levels of trafficking in Houston can be divided into transportation, demographic, and labor factors.[29] The I-10 corridor links El Paso and Houston, and thus allows easy transportation of many of the trafficking victims entering from Latin America.[1] This has made it one of the biggest human trafficking routes in the United States.[27] Additionally, Houston is a popular entryway for internationally trafficked persons due to its two large, international airports[26] and the Port of Houston, which is the largest international port in the United States and the thirteenth busiest in the world.[27] The demographic composition of Houston, with large Hispanic, Black, and Asian populations, makes it easy for trafficking victims to blend in with the local population.[27] Furthermore, Houston's thriving economy has created a huge market for laborers in industries like textiles, agriculture, restaurants, construction, and domestic work.[27] This vast diversity of industries has made it difficult for law enforcement to effectively concentrate on ending human trafficking in any one labor sector.[29] The high frequency of large sporting events, conventions, and other festivities bring in visitors from around the nation, stimulating the growth of Houston's sex industry, and making Houston a prime location for trafficking.[26]

Laws and policies

There are several pieces of legislation in place in Texas working to combat human trafficking. Recent legislation passed in Texas mandates that all incoming local law enforcement receive training on human trafficking.[30] In Houston specifically, one of the primary elements of the Juvenile Justice System is the Harris County Juvenile Probation Department (HCJPD). HCJPD is "committed to the protection of the public, utilizing intervention strategies that are community-based, family-oriented and least restrictive while emphasizing responsibility and accountability of both parent and child." Feeding into HCJPD is the juvenile court system that includes five juvenile courts (each with a different judge presiding), a juvenile mental health court, and a juvenile drug court.[26]

Organizations

- The H.U.G.S Foundation (HelpingUGrowStrong): Fights against Human Trafficking, Synthetic Drugs, & Cyber Bullying, by educating the public and assisting law enforcement in catching predators and pedophiles. Most efforts are focused locally but their reach is international, assisting in relief for children in Asia and Africa. http://www.thehugsfoundation.org

- Coalition Against Human Trafficking: works to increase community awareness of human trafficking and coordinate the identification, assistance, and protection of victims through community education, advocacy, provision of culturally and linguistically sensitive victim services, and efforts to ensure the investigation and prosecution of human traffickers.[31]

- Free the Captives: a Christian-based NGO that has objectives including educating the community, preventing, and intervening in the trafficking of at-risk teens, reducing the demand, and pursuing legal remedies to combat trafficking.[32]

- Houston Rescue and Restore: confronts modern-day slavery by educating the public, training professionals, and empowering the community to take action for the purpose of identifying, rescuing, and restoring trafficking victims to freedom.[33] Their efforts include equipping professionals in the health care industry with improved resources to recognize potential human trafficking victims as well as getting the victims in touch with support services.[34]

- CHILDREN AT RISK: A non-profit, non-partisan organization dedicated to improving the quality of life of children through strategic research, public policy analysis, education, collaboration and advocacy. The Center to End the Trafficking and Exploitation of Children has helped improve anti-trafficking laws in Texas since its inception in 2007. http://childrenatrisk.org

- Love146: an international non-profit organization dedicated to the abolition of child exploitation and sex trafficking by providing survivor care, prevention education, professional training, and encouraging grassroots empowering movements.[35]

- Mosaic Family Services: operates the Services for Victims of Trafficking Program that provides culturally and linguistically competent services to victims experiencing abuse, so that they may quickly recover from a criminal act.

- Texas Association Against Sexual Assault: educates rape centers and domestic violence shelters throughout Texas about human trafficking.

- New Friends, New Life: New Friends New Life restores and empowers formerly trafficked girls and sexually exploited women and their children.[36]

- The Key2Free: a faith-based NGO focusing on Fighting for victims rights; Relationships with law enforcement, justice system, community groups, churches and other non profits; Education and awareness to the public about sex trafficking and Emancipation and restoration of survivors of sex trafficking. http://thekey2freetx.org

- Hope Rising Ministries: a faith-based 501.C3 non-profit organization dedicated to providing hope and a future for survivors of human sex trafficking and exploitation. Uses equine assisted psychotherapy and learning and art therapy to aid in the restoration process. Also provides certification training to care givers in the internationally accepted 'Hands that Heal' curriculum. http://www.hoperisingministries.org

See also

References

- Servin, Argentina, Kimberly Brouwer, Leah Gordon, Teresita Rocha-Jimenez, and Hugo Staines. "Vulnerability Factors and Pathways Leading to Underage Entry into Sex Work in Two Mexican–US Border Cities." Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk 6, no. 1 (2015): 1-17.

- Center for Public Policy Studies. "Texas Human Trafficking Fact Sheet." (2013). Accessed November 15, 2015.

- Butler, Cheryl. "Sex Slavery in the Lone Star State: Does the Texas Human Trafficking Legislation of 2011 Protect Minors?" Akron Law Review 45 (2012): 843-85.

- "FACT SHEET: HUMAN TRAFFICKING". U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "United States Report: 1/1/2015 – 12/31/2015" (PDF). National Human Trafficking Resource Center. National Human Trafficking Resource Center. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Chacon, Jennifer. "Misery and Mypoia: Understanding the Failures of U.S. Efforts to Stop Human Trafficking." Fordham Law Review 74, no. 6 (2006): 2977-3040.

- Svitlana, Batsyukova. "Human Trafficking and Human Smuggling: Similar Nature, Different Concepts." Studies of Changing Societies: Comparative and Interdisciplinary Focus 1, no. 1 (2012): 39-49.

- "Hundreds of Young Girls Are Victimized in Texas Sex Trade Each MonthDallas Women's Foundation." Texas Non Profits. Web. 13 Apr. 2012. <http://txnp.org/Article/?ArticleID=12913>.

- "Texas." National Human Trafficking Resource Center. 2015. Accessed November 19, 2015.

- Texas Department of Public Safety. "Assessing the Threat of Human Trafficking in Texas." (2014). Accessed November 14, 2915.

- http://sites.utexas.edu/idvsa/files/2017/02/Human-Trafficking-by-the-Numbers-2016.pdf

- Hofmann, Susanne. "Borderline Slavery: Mexico, United States, and the Human Trade - Edited by Tiano, Susan and Murphy-Aguilar, Moira." Bulletin of Latin American Research 34, no. 2 (2015): 279-81. doi:10.1111.

- Schaffner, Jessica. "Optimal Deterrence: A Law and Economics Assessment of Sex and Labor Trafficking Law in the United States." Houston Law Review 51, no. 5 (2014): 1519-548.

- Srikantiah, Jayashri. "Perfect Victims and Real Survivors: The Iconic Victim in Domestic Human Trafficking Law." Boston University Law Review 87, no. 157 (2007): 157-211.

- Armendariz, Noel-Busch, Maura Nsonwu, and Lauri Heffro. "Understanding Human Trafficking: Development of Typologies of Traffickers PHASE II." First Annual Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Trafficking, 2009, 1-12.

- Chinese Restaurant in San Marcos Linked to Human Trafficking Ring

- Olsen, Lise (2008-06-29). "Crackdown on Houston sex ring freed 120 women". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2019-08-26.

- Garza, Rocio. "Addressing Human Trafficking Along the United States–Mexico Border: The Need for a Bilateral Partnership." Cardozo Journal of International and Comparative Law 19, no. 413 (2011): 413-52.

- Ugarte, Marisa B.; Zarate, Laura; Farley, Melissa (January 2004). "Prostitution and trafficking of women and children from Mexico to the United States". Journal of Trauma Practice. 2 (3/4): 147–165. doi:10.1300/J189v02n03_08.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cicero-Dominguez, Salvador. "Assessing the U.S.–Mexico Fight Against Human Trafficking and Smuggling: Unintended Results of U.S. Immigration Policy." Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights 4, no. 2 (2005): 303-30. Accessed September 24, 2015.

- Collins, Hannah. "Human Trafficking in the Indo-Asia-Pacific Region." DISAM Journal of International Security Assistance Management 3 (2014): 69-77.

- Akaha, Tsuneo. "Human Security in East Asia: Embracing Global Norms Through Regional Cooperationin Human Trafficking, Labour Migration, and HIV/AIDS." Journal of Human Security 5, no. 2 (2009): 11-34. doi:10.3316.

- "The Lost Girls". Texas Monthly. 2010-04-01. Retrieved 2019-08-26.

- U.S. Committee on Homeland Security, Combating Human Trafficking in Our Major Cities: Field Hearing before the Committee on Homeland Security, Washington D.C.: GPO, 2014.

- McGregor Perry, Kelsey, and Lindsay McEwing. "How Do Social Determinants Affect Human Trafficking in Southeast Asia, and What Can We Do about It? A Systematic Review." Health and Human Rights 15, no. 2 (2013): 138-59. JSTOR.

- Web. 16 Mar. 2012. <http://www.houstonrr.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Domestic-Minor-Sex-Trafficking-Field-Assessment-Harris-and-Galveston-Cty.pdf Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine>.

- Elom Ngwe, Job, and O. Oko Elechi. "Human Trafficking: The Modern Day Slavery of the 21st Century." African Journal of Criminology and Justice Studies 6, no. 1/2 (2012): 103-19. SocINDEX.

- "Free Our City." Free Our City. Web. 17 Mar. 2012. <http://freeourcity.org/ Archived 2012-11-09 at the Wayback Machine>.

- Rescue & Restore Coalition. "Texas Facts on Human Traffickin."Texasimpact.org/UMW/HumanTraffickFactSheet.doc. Web. 22 Feb. 2012.

- "ctcaht.org - This website is for sale! - ctcaht Resources and Information". ctcaht.org. Retrieved 2019-08-26.

- "HumanTrafficking.org | United States of America: Non-Governmental Organizations." HumanTrafficking.org: A Web Resource for Combating Human Trafficking in the East Asia Pacific Region. Web. 13 Apr. 2012. <"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-14. Retrieved 2012-04-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)>.

- "About Free the Captives." Free the Captives: Anti-human Trafficking, Houston, TX. Web. 13 Apr. 2012. <"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-05-04. Retrieved 2012-04-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)>.

- "Mission, Vision, Values | Houston Rescue and Restore Coalition." Houston Rescue and Restore Coalition. Web. 13 Apr. 2012. <"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2012-04-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)>.

- Isaac, Reena; Solak, Jennifer; Giardino, Angelo P (2011). "Health Care Providers' Training Needs Related to Human Trafficking: Maximizing the Opportunity to Effectively Screen and Intervene". Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk. 2 (1). ISSN 2155-5834.

- "Love146". Love146.

- "New Friends, New Life home page". 2015-04-18. Retrieved 2015-04-18.