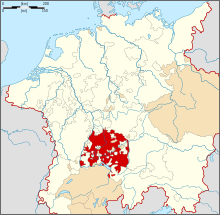

Schwäbisch Hall

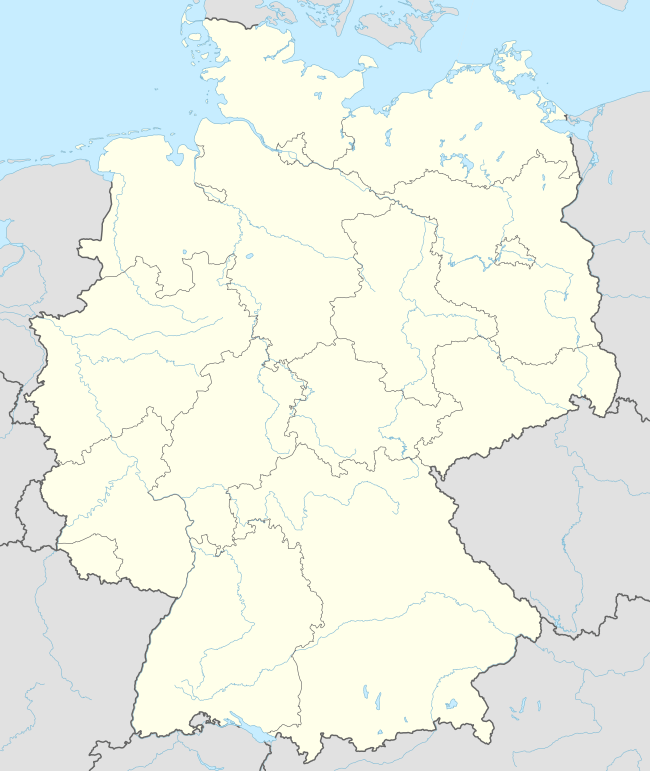

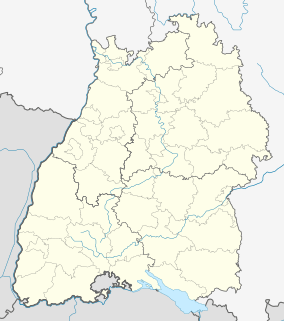

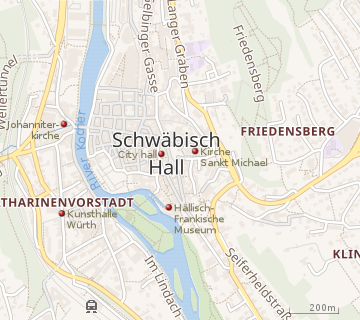

Schwäbisch Hall (German pronunciation: [ˈʃvɛːbɪʃ ˈhal]; "Swabian Hall"), or Hall for short,[2] is a town in the German state of Baden-Württemberg and capital of the district of Schwäbisch Hall. The town is located in the valley of the Kocher river in the north-eastern part of Baden-Württemberg.

Schwäbisch Hall | |

|---|---|

Marktplatz in Christmas time | |

Coat of arms | |

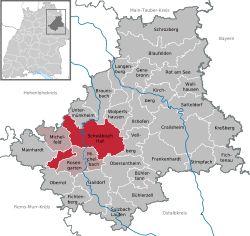

Location of Schwäbisch Hall within Schwäbisch Hall district  | |

Schwäbisch Hall  Schwäbisch Hall | |

| Coordinates: 49°6′44″N 9°44′15″E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Baden-Württemberg |

| Admin. region | Stuttgart |

| District | Schwäbisch Hall |

| Subdivisions | Kernstadt and 8 Stadtteile |

| Government | |

| • Lord Mayor | Hermann-Josef Pelgrim (SPD) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 104.23 km2 (40.24 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 304 m (997 ft) |

| Population (2018-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 40,440 |

| • Density | 390/km2 (1,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 74523 |

| Dialling codes | 0791, 07907 (Sulzdorf, Tüngental), 07977 (Sittenhardt, Wielandsweiler) |

| Vehicle registration | SHA, CR |

| Website | www.schwaebischhall.de |

Hall was a Free Imperial City for five centuries until it was annexed by Württemberg in 1802.

Etymology

"Schwäbisch" refers to the Swabian League (German: Schwäbischer Bund). The origin of the second part of the name, "Hall", is unclear. It might be derived from a West Germanic word family that means "drying something by heating it", possibly referring to the open-pan salt making method[3] used there until the saltworks closed down in 1925.[4]

History

Early history

Imperial City of [Swabian] Hall Reichsstadt [Schwäbisch] Hall | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1280–1802 | |||||||||

| Status | Free Imperial City of the Holy Roman Empire | ||||||||

| Capital | Schwäbisch Hall | ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Founded | Uncertain | ||||||||

• Gained Imperial immediacy | 1280 | ||||||||

• Erste Zwietracht | 1340 | ||||||||

• Zweite Zwietracht | 1510–12 | ||||||||

| 1650 | |||||||||

• Mediatised to Württemberg | 1802 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Salt was produced from brine by the Celts at the site of Schwäbisch Hall as early as the fifth century BCE.[5] The town was first mentioned in a document called Öhringer Stiftungsbrief dating from 1063.[5] The village probably belonged first to the Counts of Comburg-Rothenburg and went from them to the Imperial house of Hohenstaufen (ca 1116). It was probably Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa who founded the imperial mint and started the coining of the so-called Heller. Hall flourished through the production of salt and coins. Since 1204 it has been called a town.[5]

After the fall of the house of Hohenstaufen, Hall defended itself successfully against the claims of a noble family in the neighbourhood[5] (the Schenken von Limpurg). The conflict was finally settled in 1280 by Rudolph I of Habsburg; this allowed the undisturbed development into a Free Imperial City (Reichsstadt) of the Holy Roman Empire. Emperor Louis IV the Bavarian granted a constitution that settled internal conflicts (Erste Zwietracht) in 1340. After this, the city was governed by the inner council (Innerer Rat) which was composed by twelve noblemen, six "middle burghers" and eight craftsmen. The head of the council was the Stättmeister (mayor). A second phase of internal conflicts 1510–12 (Zweite Zwietracht) brought the dominating role of the nobility to an end. The confrontation with the noble families was started by Stättmeister Hermann Büschler, whose daughter Anna Büschler is the subject of a popular book by Harvard professor Steven Ozment ("The Bürgermeister's Daughter: Scandal in a sixteenth-century German town"). The leading role was taken over by a group of families who turned into a new ruling class. Amongst them where the Bonhöffers, the ancestors of Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

Middle ages

From the 14th to the 16th centuries, Hall systematically acquired a large territory in the surrounding area, mostly from noble families and the Comburg monastery. The wealth of this era can still be seen in some gothic buildings like St. Michael's Church (rebuilt 1427–1526) with its impressive stairway (1507). The town joined the Protestant Reformation very early. Johannes Brenz, a follower of Martin Luther, was made pastor of St. Michael's Church in 1522 and quickly began to reform the church and the school system along Lutheran lines.

Hall suffered severely during the Thirty Years' War, though it was never besieged or scene of a battle. However, it was forced to pay enormous sums to the armies of the various parties, especially to the imperial, Swedish and French troops, who also committed numerous atrocities and plundered the town and the surrounding area. Between 1634 and 1638 every fifth inhabitant died of hunger and diseases, especially from the bubonic plague. The war left the town an impoverished and economically ruined place. But with the help of reorganizations of salt production and trade and a growing wine trade, there was an astonishingly fast recovery.

17th century to early 20th century

Fires were a constant threat to the mostly wooden houses of the town. The great fires of 1680 and especially of 1728 destroyed much of the city, which led to new buildings in the Baroque style, such as the city hall.

The Napoleonic wars brought the history of Hall as a Free Imperial City to an end. Following the Treaty of Lunéville (1801), the duke of Württemberg was allowed by Napoleon to occupy the town and several other minor states as a compensation for territories on the Left Bank of the Rhine that fell to France. This took place in 1802 — Hall lost its territory and its political independence and became a Oberamtsstadt (seat of an Oberamt, comparable to a county). Ownership of the salt works was handed over to the state. A long economic crisis during the 19th century forced many citizens to move to other places in Germany or to emigrate overseas, mostly to the United States. While other towns like Heilbronn grew steadily due to the Industrial Revolution, the population of Hall stagnated. The economic situation improved during the second half of the 19th century — a main factor was the railway line to Heilbronn (1862) — but was not followed by a significant growth of the town. It was not until the 1920s and 1930s that new settlements were built on the heights surrounding the old town. Hall also grew through the incorporation of Steinbach (1930) and Hessental (1936).

In 1827, a health spa was established on one of the islands in the Kocher river. Especially after the building of the railway (1862) it became a considerable economical factor. The well-preserved old town also brought a rising number of tourists. Since the beginning of the 20th century, Hall has developed many festivities. Especially well known are the theatre productions which are performed every year in the centre of the city on the steps of St. Michael.

Nazi Germany and World War II

In 1934, Hall was officially named Schwäbisch Hall. During the Third Reich a Luftwaffe air base was built at Hessental.[5] During Kristallnacht on 9 November 1938, local Nazis burned the synagogue in Steinbach and devastated shops and houses of Jewish citizens.[5] Approximately 40 Jewish citizens of Schwäbisch Hall fell victim to the Holocaust in extermination camps in Eastern Europe.[5] In 1944 a concentration camp was established next to the train station Hall-Hessental. The train station at Hall was targeted by an American air raid on February 23, 1945, but the devastation was mostly limited to the suburbs of St. Katharina and Unterlimpurg. The town was occupied by US Army troops on April 17, 1945 without serious resistance; though several buildings were destroyed or damaged, the historical old town suffered comparatively little.

Post World War II

In 1960, Schwäbisch Hall reached the status of a Große Kreisstadt.[5] This means that the city took over some tasks of the district.[5] From the end of World War II until the end of the Cold War, Dolan Barracks and Schwäbisch Hall Army Air Field was a kaserne which hosted a series of US Army aviation units and ordnance units until it was turned back over to German control in 1993.[6]

Demographics

As of December 31, 2009, Schwäbisch Hall has a population of 36,799. The residents of Schwäbisch Hall come from over 100 countries.[7] As of December 31, 2008, there are 18,838 Protestants, 7,375 Roman Catholics and 10,234 who are either in another religion or not religious.[8] In 2017 Schwäbisch Hall had a population of over 39,000.

Architecture

Schwäbisch Hall has a mix of historic and modern buildings.[7] The older are mostly medieval, and with Timber Frame, Gothic and Baroque styles dominating the city center. The more modern are on the outskirts and suburbs, helping preserve the history of the city.

|

City hall by night.

City hall by night..jpg) Ensemble of houses with modern Kunsthalle Würth

Ensemble of houses with modern Kunsthalle Würth- Johanniterhalle, exhibition site of Darmstadt Madonna

Culture

There is an outdoor summer theater which performs on the open-air staircase at St. Michael's Church and at the Globe Theatre.[2] The Hällisch-Frankische Museum and the Hohenloher Freilandmuseum (Wackershofen open air museum) shows the history of the region starting from the Middle Ages.[2]

The Kunsthalle Würth, a modern art gallery, can be explored to see paintings, graphic art, and sculptures dating from the 19th century onward.[2] Schwäbisch Hall and the surrounding area offer a plenty of leisure activities which includes sports flying, swimming, hiking and cycling.[2]

Other parts of the city's culture includes the Salt Festival where the historical salt economy of the town is celebrated, the Summer Night Festival, the Baker's Oven Festival and the Christmas Market which includes traditional handicrafts.[9]

Education

Schwäbisch Hall has a long tradition as a city of learning.[10]

Schwäbisch Hall offers education opportunities through vocational schools and various technical schools. Programs are offered in schools such as Schwäbisch Hall Evangelical School of Social Work, Social Service Department of Social Professions, Protestant vocational school for the elderly, School of Alternative Education Nursing, School of Nursing and the Ayurvedic teaching and training institute, the Institute of Ayurveda and Yoga.[10]

Due to a branch of the Goethe-Institut at Schwäbisch Hall, the town attracts up to 2,000 students a year, coming from countries around the world to study the German language.[11] The programs are especially popular during the summer, as college students attend the program over their break to earn credits and improve their German.

The City Archives Hall is a documentation centre, which allows for historical research and memory management.[12] The duties of the City Archives Hall are the ordering, preparing, evaluating and management of its archives and collections, to support historical research, to collaborate in exhibitions and to publish its own or other publications on the history of Schwäbisch Hall.[12]

The archive keeps official records and files of the present city administration and its predecessors, and of collection items of different type and origin, which refer to the city, such as photographs, posters, graphics, paintings, maps and plans, or a newspaper clipping collection.[12] There are also extensive library collections in the literature on the history of Schwäbisch Hall and the region, as well as valuable historical prints.[12]

Politics

Hermann-Josef Pelgrim is the current Lord Mayor.[7] The city administration was an early mover in the migration from Microsoft Windows to GNU/Linux and open source software in the early years of the 21st century.[13]

Next scheduled elections for citizens of Schwäbisch Hall

| Election | Timeframe | Length of term | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mayor | Spring 2013 | 8 Years | [14] |

| Federal | Autumn 2013 | 4 years | |

| Ortschaftsrat | Summer 2014 | 5 years | |

| Council | Summer 2014 | 5 years | |

| District Council | Summer 2014 | 5 years | |

| European Parliament | Summer 2014 | 5 years | |

| State | Spring 2016 | 5 years |

Economy

Schwäbisch Hall is the most important regional economic hub between Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Nuremberg.[15] Formerly, salt was important to Schwäbisch Hall,[7] but today the economy is shaped by a group of medium-sized companies,[5] focusing mainly on trade and services sectors.[2] A number of businesses dealing in property finance, solar energy and telecommunications sectors also have their headquarters in Schwäbisch Hall.[2] Notable companies are Bausparkasse Schwäbisch Hall AG, a housing credit company, founded in 1944 and RECARO Aircraft Seating, an aircraft seats manufacturer.

Annually, there are up to 600 overnight stays in Schwäbisch Hall hotels by Goethe-Institut students.[11]

| overnight stays | Source | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 193,213 | [16] |

| By foreigners | 41,600 | |

| Tax rates | Rate | Source |

| Land tax A | 400 v.H. | [16] |

| Land tax B | 400 v.H. | |

| Trade tax | 280 v.H. | |

| Retail trade | Source | |

| Catchment area | 160,000 people | [16] |

| Town SHA | 305.1 Mio. Euro | |

| Per capita | 8,320 Euro | |

| Purchasing power of town | 100.2 | |

| Employment stats | Source | |

| People employed and subjected to social insurance | 20,563 | [16] |

| producing trade | 5,188 | |

| trade, restaurants and traffic | 3,424 | |

| service sector | 11,951 | |

| Incoming commuters | 12,119 | |

| Outgoing commuters | 4,809 | |

| Unemployment rate | 4.5% |

Transport

Roads

Schwäbisch Hall has an exit on the Autobahn 6 (Heilbronn–Nürnberg). Federal highways 14 (Stuttgart–Nürnberg) and 19 (Ulm–Aalen–Schwäbisch Hall–Würzburg) also run through the town.

Railways

Schwäbisch Hall-Hessental station is at the junction of the Waiblingen–Schwäbisch Hall railway and the Crailsheim–Heilbronn railway and Schwäbisch Hall station (the town station) is on the Crailsheim–Heilbronn railway.

Health

Schwäbisch Hall has a history with brine.[17] The first brine bath started in 1827.[17] Diakonie-Krankenhaus, with 574 beds, is the main hospital in Schwäbisch Hall.[17] There are 100 general practitioners, medical specialists and physiotherapists in Schwäbisch Hall.[17] There are health fairs such as Well-Vital Health Fair and the Haller Gesundheits- und Naturheiltagen in Schwäbisch Hall.[17]

Sports

The sports played in Schwäbisch Hall include swimming, light athletics, tennis, shooting, soccer, baseball, handball and American football.[18] There are 22 sports halls and 25 outdoor playing fields.[18] The Schwäbisch Hall Unicorns have been among the preeminent German American football teams ever since their two national championships in 2011 and 2012. The Unicorns are further notable for being the former team of Moritz Böhringer.

People from Schwäbisch Hall

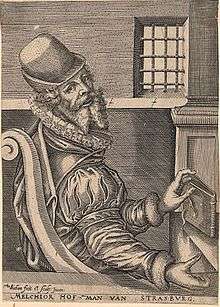

- Melchior Hofmann (around 1500–1543), Baptist leader

- Thomas Schweicker (1540-1602), Famous artist who was notable for his lack of arms.

- Johann Ulrich Steigleder (1593–1635), composer and organist

- Louis Brown (1836–1916), professor of art and important history painter in Munich

- Otto Ruff (1871–1939), chemist

- Walter Haeussermann, (1914–2010), German-American aerospace engineer and physicist[19]

- Hans Beißwenger, (1916–1943), Luftwaffe pilot

- Wolfgang Gönnenwein (1933–2015), conductor, music educator and politician

- Walter Müller, (born 1943), physician and politician (SPD)

- Joachim Rücker (born 1951), diplomat, Special Envoy of the UN Secretary General and Head of United Nations Human Rights Council

- Susanne Erding-Swiridoff also known as Susanne Zargar Swiridoff (born 1955), a well known music composer and recipient of many national and international prizes, including the prestigious award of the Deutsche Villa Massimo. She teaches non-European music at Stuttgart music academy.

- Heinrich Schmieder (1970–2010), German actor known for playing Rochus Misch in Downfall (Der Untergang).

- Marco Sailer, (born 1985), footballer for SV Darmstadt 98

- Tobias Weis, (born 1985), footballer for TSG 1899 Hoffenheim.[20]

- Louk Sorensen, (born 1985), Irish professional tennis player

- Jonas Koch (born 1993), cyclist

- Bahram Nikmard (born 1974 in Tehran), painter, living in Hall since 2003.[21]

Twin towns - sister cities

Schwäbisch Hall is twinned with:[22]

References

- "Bevölkerung nach Nationalität und Geschlecht am 31. Dezember 2018". Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg (in German). July 2019.

- The city of Schwäbisch Hall, Goethe-Institut, retrieved March 22, 2011

- Kuno Ulshöfer, Herta Beutter (ed.): Hall und das Salz. Beiträge zur hällischen Stadt- und Salinengeschichte, Sigmaringen 1982, p. 8.

- "Schwäbisch Hall". castleroad.de. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- The history of Schwäbisch Hall - an overview, Schwäbisch Hall, retrieved March 23, 2011

- Elkins, Walter. "U.S. ARMY INSTALLATIONS - HEILBRONN". USARMYGERMANY.COM. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Welcome, Schwäbisch Hall, retrieved March 23, 2011

- "Religion" (in German). Schwäbisch Hall. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- GmbH, Q4U. "Festivals and Celebrations – City Schwäbisch Hall". www.schwaebischhall.de. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- "Schulen in Schwäbisch Hall" (in German). Schwäbisch Hall. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- Goethe-Institute, Schwäbisch Hall, retrieved March 23, 2011

- "Stadt- und Hospitalarchiv" (in German). Schwäbisch Hall. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "Open Source for municipalities". Schwäbisch Hall. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- "Wahlen in Schwäbisch Hall". Schwäbisch Hall. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- Learning German in Schwäbisch Hall, Goethe Institute, retrieved March 22, 2011

- "Overview of Economic Data". Schwäbisch Hall. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- "Health and Wellness". Schwäbisch Hall. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- The sports city, Schwäbisch Hall, retrieved March 23, 2011

- "Walter Haeussermann". stimme.de. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- "Tobias Weis". TSG 1899 Hoffenheim. Archived from the original on September 6, 2009. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- "Bahram Nikmard". gallery44.co.uk Contemprary Art. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "Schwäbisch Hall und ihre Partnerstädte". schwaebischhall.de (in German). Schwäbisch Hall. Retrieved 2019-11-28.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Schwäbisch Hall. |

- Official website (in English)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.