Linux

Linux (/ˈlinʊks/ (![]()

| |

| Developer | Community Linus Torvalds |

|---|---|

| Written in | C, Assembly language |

| OS family | Unix-like |

| Working state | Current |

| Source model | Open source |

| Initial release | September 17, 1991 |

| Marketing target | Cloud computing, embedded devices, mainframe computers, mobile devices, personal computers, servers, supercomputers |

| Available in | Multilingual |

| Platforms | Alpha, ARC, ARM, C6x, AMD64, H8/300, Hexagon, Itanium, m68k, Microblaze, MIPS, NDS32, Nios II, OpenRISC, PA-RISC, PowerPC, RISC-V, s390, SuperH, SPARC, Unicore32, x86, XBurst, Xtensa |

| Kernel type | Monolithic |

| Userland | GNU[lower-alpha 1] |

| Default user interface | Unix shell |

| License | GPLv2[7] and others (the name "Linux" is a trademark[lower-alpha 2]) |

| Official website | www |

Distributions include the Linux kernel and supporting system software and libraries, many of which are provided by the GNU Project. Many Linux distributions use the word "Linux" in their name, but the Free Software Foundation uses the name GNU/Linux to emphasize the importance of GNU software, causing some controversy.[14][15]

Popular Linux distributions[16][17][18] include Debian, Fedora, and Ubuntu. Commercial distributions include Red Hat Enterprise Linux and SUSE Linux Enterprise Server. Desktop Linux distributions include a windowing system such as X11 or Wayland, and a desktop environment such as GNOME or KDE Plasma. Distributions intended for servers may omit graphics altogether, or include a solution stack such as LAMP. Because Linux is freely redistributable, anyone may create a distribution for any purpose.[19]

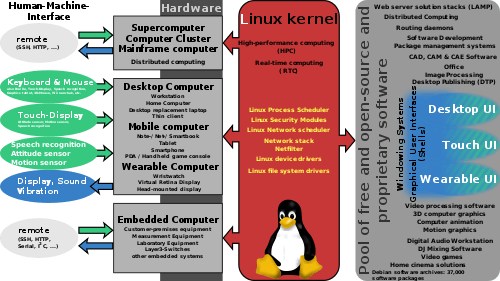

Linux was originally developed for personal computers based on the Intel x86 architecture, but has since been ported to more platforms than any other operating system.[20] Because of the dominance of Android on smartphones, Linux also has the largest installed base of all general-purpose operating systems.[22] Although it is used by only around 2.3 percent of desktop computers,[24] the Chromebook, which runs the Linux kernel-based Chrome OS, dominates the US K–12 education market and represents nearly 20 percent of sub-$300 notebook sales in the US.[25] Linux is the leading operating system on servers (over 96.4% of the top 1 million web servers' operating systems are Linux),[26] leads other big iron systems such as mainframe computers, and is the only OS used on TOP500 supercomputers (since November 2017, having gradually eliminated all competitors).[27][28][29]

Linux also runs on embedded systems, i.e. devices whose operating system is typically built into the firmware and is highly tailored to the system. This includes routers, automation controls, smart home technology (like Google Nest),[30] televisions (Samsung and LG Smart TVs use Tizen and WebOS, respectively),[31][32][33] automobiles (for example, Tesla, Audi, Mercedes-Benz, Hyundai, and Toyota all rely on Linux),[34] digital video recorders, video game consoles, and smartwatches.[35] The Falcon 9's and the Dragon 2's avionics use a customized version of Linux.[36]

Linux is one of the most prominent examples of free and open-source software collaboration. The source code may be used, modified and distributed commercially or non-commercially by anyone under the terms of its respective licenses, such as the GNU General Public License.[19]

History

Precursors

.jpg)

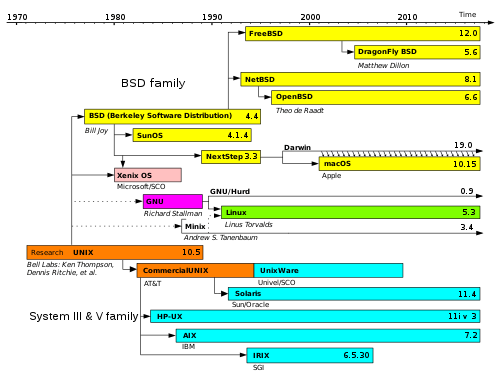

The Unix operating system was conceived and implemented in 1969, at AT&T's Bell Laboratories in the United States by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, Douglas McIlroy, and Joe Ossanna.[37] First released in 1971, Unix was written entirely in assembly language, as was common practice at the time. In 1973 in a key, pioneering approach, it was rewritten in the C programming language by Dennis Ritchie (with the exception of some hardware and I/O routines). The availability of a high-level language implementation of Unix made its porting to different computer platforms easier.[38]

Due to an earlier antitrust case forbidding it from entering the computer business, AT&T was required to license the operating system's source code to anyone who asked. As a result, Unix grew quickly and became widely adopted by academic institutions and businesses. In 1984, AT&T divested itself of Bell Labs; freed of the legal obligation requiring free licensing, Bell Labs began selling Unix as a proprietary product, where users were not legally allowed to modify Unix. The GNU Project, started in 1983 by Richard Stallman, had the goal of creating a "complete Unix-compatible software system" composed entirely of free software. Work began in 1984.[39] Later, in 1985, Stallman started the Free Software Foundation and wrote the GNU General Public License (GNU GPL) in 1989. By the early 1990s, many of the programs required in an operating system (such as libraries, compilers, text editors, a Unix shell, and a windowing system) were completed, although low-level elements such as device drivers, daemons, and the kernel, called GNU/Hurd, were stalled and incomplete.[40]

Linus Torvalds has stated that if the GNU kernel had been available at the time (1991), he would not have decided to write his own.[41] Although not released until 1992, due to legal complications, development of 386BSD, from which NetBSD, OpenBSD and FreeBSD descended, predated that of Linux. Torvalds has also stated that if 386BSD had been available at the time, he probably would not have created Linux.[42]

MINIX was created by Andrew S. Tanenbaum, a computer science professor, and released in 1987 as a minimal Unix-like operating system targeted at students and others who wanted to learn the operating system principles. Although the complete source code of MINIX was freely available, the licensing terms prevented it from being free software until the licensing changed in April 2000.[43]

Creation

In 1991, while attending the University of Helsinki, Torvalds became curious about operating systems.[44] Frustrated by the licensing of MINIX, which at the time limited it to educational use only,[43] he began to work on his own operating system kernel, which eventually became the Linux kernel.

Torvalds began the development of the Linux kernel on MINIX and applications written for MINIX were also used on Linux. Later, Linux matured and further Linux kernel development took place on Linux systems.[45] GNU applications also replaced all MINIX components, because it was advantageous to use the freely available code from the GNU Project with the fledgling operating system; code licensed under the GNU GPL can be reused in other computer programs as long as they also are released under the same or a compatible license. Torvalds initiated a switch from his original license, which prohibited commercial redistribution, to the GNU GPL.[46] Developers worked to integrate GNU components with the Linux kernel, making a fully functional and free operating system.[47]

Naming

Linus Torvalds had wanted to call his invention "Freax", a portmanteau of "free", "freak", and "x" (as an allusion to Unix). During the start of his work on the system, some of the project's makefiles included the name "Freax" for about half a year. Torvalds had already considered the name "Linux", but initially dismissed it as too egotistical.[48]

In order to facilitate development, the files were uploaded to the FTP server (ftp.funet.fi) of FUNET in September 1991. Ari Lemmke, Torvalds' coworker at the Helsinki University of Technology (HUT), who was one of the volunteer administrators for the FTP server at the time, did not think that "Freax" was a good name. So, he named the project "Linux" on the server without consulting Torvalds.[48] Later, however, Torvalds consented to "Linux".

According to a newsgroup post by Torvalds[9], the word "Linux" should be pronounced (/ˈlɪnʊks/ (![]()

![]()

![]()

Commercial and popular uptake

Adoption of Linux in production environments, rather than being used only by hobbyists, started to take off first in the mid-1990s in the supercomputing community, where organizations such as NASA started to replace their increasingly expensive machines with clusters of inexpensive commodity computers running Linux. Commercial use began when Dell and IBM, followed by Hewlett-Packard, started offering Linux support to escape Microsoft's monopoly in the desktop operating system market.[50]

Today, Linux systems are used throughout computing, from embedded systems to virtually all supercomputers,[29][51] and have secured a place in server installations such as the popular LAMP application stack. Use of Linux distributions in home and enterprise desktops has been growing.[52][53][54][55][56][57][58] Linux distributions have also become popular in the netbook market, with many devices shipping with customized Linux distributions installed, and Google releasing their own Chrome OS designed for netbooks.

Linux's greatest success in the consumer market is perhaps the mobile device market, with Android being one of the most dominant operating systems on smartphones and very popular on tablets and, more recently, on wearables. Linux gaming is also on the rise with Valve showing its support for Linux and rolling out SteamOS, its own gaming-oriented Linux distribution. Linux distributions have also gained popularity with various local and national governments, such as the federal government of Brazil.[59]

Current development

Greg Kroah-Hartman is the lead maintainer for the Linux kernel and guides its development.[60] William John Sullivan is the executive director of the Free Software Foundation,[61] which in turn supports the GNU components.[62] Finally, individuals and corporations develop third-party non-GNU components. These third-party components comprise a vast body of work and may include both kernel modules and user applications and libraries.

Linux vendors and communities combine and distribute the kernel, GNU components, and non-GNU components, with additional package management software in the form of Linux distributions.

Design

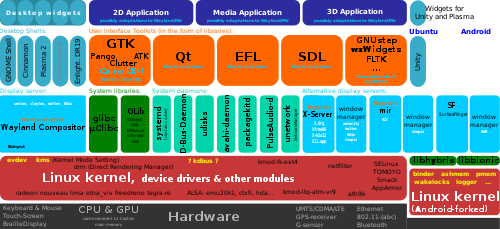

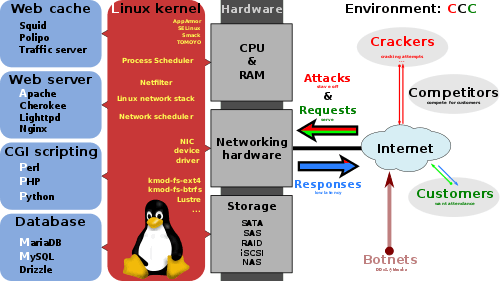

Many open source developers agree that the Linux kernel was not designed, rather it evolved through Natural Selection. Torvalds considers that although the design of Unix served as a scaffolding, "Linux grew with a lot of mutations - and because the mutations were less than random, they were faster and more directed than alpha-particles in DNA." [63] Raymond considers Linux's revolutionary aspects to be social, not technical, before Linux complex software was designed carefully by small groups, but "Linux evolved in a completely different way. From nearly the beginning, it was rather casually hacked on by huge numbers of volunteers coordinating only through the Internet. Quality was maintained not by rigid standards or autocracy but by the naively simple strategy of releasing every week and getting feedback from hundreds of users within days, creating a sort of rapid Darwinian selection on the mutations introduced by developers."[64] Bryan Cantrill, an engineer of a competing OS, agrees that "Linux wasn't designed, it evolved", but considers this to be a limitation, proposing that some features, especially those related to security[65], cannot be evolved into, "this is not a biological system at the end of the day, it's a software system." [66] A Linux-based system is a modular Unix-like operating system, deriving much of its basic design from principles established in Unix during the 1970s and 1980s. Such a system uses a monolithic kernel, the Linux kernel, which handles process control, networking, access to the peripherals, and file systems. Device drivers are either integrated directly with the kernel, or added as modules that are loaded while the system is running.[67]

The GNU userland is a key part of most systems based on the Linux kernel, with Android being the notable exception. The Project's implementation of the C library works as a wrapper for the system calls of the Linux kernel necessary to the kernel-userspace interface, the toolchain is a broad collection of programming tools vital to Linux development (including the compilers used to build the Linux kernel itself), and the coreutils implement many basic Unix tools. The project also develops Bash, a popular CLI shell. The graphical user interface (or GUI) used by most Linux systems is built on top of an implementation of the X Window System.[68] More recently, the Linux community seeks to advance to Wayland as the new display server protocol in place of X11. Many other open-source software projects contribute to Linux systems.

| User mode | User applications | For example, bash, LibreOffice, GIMP, Blender, 0 A.D., Mozilla Firefox, etc. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-level system components: | System daemons: systemd, runit, logind, networkd, PulseAudio, ... |

Windowing system: X11, Wayland, SurfaceFlinger (Android) |

Other libraries: GTK+, Qt, EFL, SDL, SFML, FLTK, GNUstep, etc. |

Graphics: Mesa, AMD Catalyst, ... | ||

| C standard library | open(), exec(), sbrk(), socket(), fopen(), calloc(), ... (up to 2000 subroutines)glibc aims to be fast, musl and uClibc target embedded systems, bionic written for Android, etc. All aim to be POSIX/SUS-compatible. | |||||

| Kernel mode | Linux kernel | stat, splice, dup, read, open, ioctl, write, mmap, close, exit, etc. (about 380 system calls)The Linux kernel System Call Interface (SCI, aims to be POSIX/SUS-compatible) | ||||

| Process scheduling subsystem |

IPC subsystem |

Memory management subsystem |

Virtual files subsystem |

Network subsystem | ||

| Other components: ALSA, DRI, evdev, LVM, device mapper, Linux Network Scheduler, Netfilter Linux Security Modules: SELinux, TOMOYO, AppArmor, Smack | ||||||

| Hardware (CPU, main memory, data storage devices, etc.) | ||||||

Installed components of a Linux system include the following:[68][69]

- A bootloader, for example GNU GRUB, LILO, SYSLINUX, or Gummiboot. This is a program that loads the Linux kernel into the computer's main memory, by being executed by the computer when it is turned on and after the firmware initialization is performed.

- An init program, such as the traditional sysvinit and the newer systemd, OpenRC and Upstart. This is the first process launched by the Linux kernel, and is at the root of the process tree: in other terms, all processes are launched through init. It starts processes such as system services and login prompts (whether graphical or in terminal mode).

- Software libraries, which contain code that can be used by running processes. On Linux systems using ELF-format executable files, the dynamic linker that manages use of dynamic libraries is known as ld-linux.so. If the system is set up for the user to compile software themselves, header files will also be included to describe the interface of installed libraries. Besides the most commonly used software library on Linux systems, the GNU C Library (glibc), there are numerous other libraries, such as SDL and Mesa.

- C standard library is the library needed to run C programs on a computer system, with the GNU C Library being the standard. For embedded systems, alternatives such as the musl, EGLIBC (a glibc fork once used by Debian) and uClibc (which was designed for uClinux) have been developed, although the last two are no longer maintained. Android uses its own C library, Bionic.

- Basic Unix commands, with GNU coreutils being the standard implementation. Alternatives exist for embedded systems, such as the copyleft BusyBox, and the BSD-licensed Toybox.

- Widget toolkits are the libraries used to build graphical user interfaces (GUIs) for software applications. Numerous widget toolkits are available, including GTK and Clutter developed by the GNOME project, Qt developed by the Qt Project and led by Digia, and Enlightenment Foundation Libraries (EFL) developed primarily by the Enlightenment team.

- A package management system, such as dpkg and RPM. Alternatively packages can be compiled from binary or source tarballs.

- User interface programs such as command shells or windowing environments.

User interface

The user interface, also known as the shell, is either a command-line interface (CLI), a graphical user interface (GUI), or controls attached to the associated hardware, which is common for embedded systems. For desktop systems, the default user interface is usually graphical, although the CLI is commonly available through terminal emulator windows or on a separate virtual console.

CLI shells are text-based user interfaces, which use text for both input and output. The dominant shell used in Linux is the Bourne-Again Shell (bash), originally developed for the GNU project. Most low-level Linux components, including various parts of the userland, use the CLI exclusively. The CLI is particularly suited for automation of repetitive or delayed tasks and provides very simple inter-process communication.

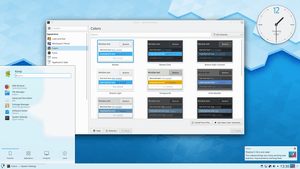

On desktop systems, the most popular user interfaces are the GUI shells, packaged together with extensive desktop environments, such as KDE Plasma, GNOME, MATE, Cinnamon, LXDE, Pantheon and Xfce, though a variety of additional user interfaces exist. Most popular user interfaces are based on the X Window System, often simply called "X". It provides network transparency and permits a graphical application running on one system to be displayed on another where a user may interact with the application; however, certain extensions of the X Window System are not capable of working over the network.[70] Several X display servers exist, with the reference implementation, X.Org Server, being the most popular.

Server distributions might provide a command-line interface for developers and administrators, but provide a custom interface towards end-users, designed for the use-case of the system. This custom interface is accessed through a client that resides on another system, not necessarily Linux based.

Several types of window managers exist for X11, including tiling, dynamic, stacking and compositing. Window managers provide means to control the placement and appearance of individual application windows, and interact with the X Window System. Simpler X window managers such as dwm, ratpoison, i3wm, or herbstluftwm provide a minimalist functionality, while more elaborate window managers such as FVWM, Enlightenment or Window Maker provide more features such as a built-in taskbar and themes, but are still lightweight when compared to desktop environments. Desktop environments include window managers as part of their standard installations, such as Mutter (GNOME), KWin (KDE) or Xfwm (xfce), although users may choose to use a different window manager if preferred.

Wayland is a display server protocol intended as a replacement for the X11 protocol; as of 2014, it has not received wider adoption. Unlike X11, Wayland does not need an external window manager and compositing manager. Therefore, a Wayland compositor takes the role of the display server, window manager and compositing manager. Weston is the reference implementation of Wayland, while GNOME's Mutter and KDE's KWin are being ported to Wayland as standalone display servers. Enlightenment has already been successfully ported since version 19.

Video input infrastructure

Linux currently has two modern kernel-userspace APIs for handling video input devices: V4L2 API for video streams and radio, and DVB API for digital TV reception.[71]

Due to the complexity and diversity of different devices, and due to the large number of formats and standards handled by those APIs, this infrastructure needs to evolve to better fit other devices. Also, a good userspace device library is the key of the success for having userspace applications to be able to work with all formats supported by those devices.[72][73]

Development

The primary difference between Linux and many other popular contemporary operating systems is that the Linux kernel and other components are free and open-source software. Linux is not the only such operating system, although it is by far the most widely used. Some free and open-source software licenses are based on the principle of copyleft, a kind of reciprocity: any work derived from a copyleft piece of software must also be copyleft itself. The most common free software license, the GNU General Public License (GPL), is a form of copyleft, and is used for the Linux kernel and many of the components from the GNU Project.[75]

Linux-based distributions are intended by developers for interoperability with other operating systems and established computing standards. Linux systems adhere to POSIX,[76] SUS,[77] LSB, ISO, and ANSI standards where possible, although to date only one Linux distribution has been POSIX.1 certified, Linux-FT.[78][79]

Free software projects, although developed through collaboration, are often produced independently of each other. The fact that the software licenses explicitly permit redistribution, however, provides a basis for larger-scale projects that collect the software produced by stand-alone projects and make it available all at once in the form of a Linux distribution.

Many Linux distributions manage a remote collection of system software and application software packages available for download and installation through a network connection. This allows users to adapt the operating system to their specific needs. Distributions are maintained by individuals, loose-knit teams, volunteer organizations, and commercial entities. A distribution is responsible for the default configuration of the installed Linux kernel, general system security, and more generally integration of the different software packages into a coherent whole. Distributions typically use a package manager such as apt, yum, zypper, pacman or portage to install, remove, and update all of a system's software from one central location.[80]

Community

A distribution is largely driven by its developer and user communities. Some vendors develop and fund their distributions on a volunteer basis, Debian being a well-known example. Others maintain a community version of their commercial distributions, as Red Hat does with Fedora, and SUSE does with openSUSE.[81][82]

In many cities and regions, local associations known as Linux User Groups (LUGs) seek to promote their preferred distribution and by extension free software. They hold meetings and provide free demonstrations, training, technical support, and operating system installation to new users. Many Internet communities also provide support to Linux users and developers. Most distributions and free software / open-source projects have IRC chatrooms or newsgroups. Online forums are another means for support, with notable examples being LinuxQuestions.org and the various distribution specific support and community forums, such as ones for Ubuntu, Fedora, and Gentoo. Linux distributions host mailing lists; commonly there will be a specific topic such as usage or development for a given list.

There are several technology websites with a Linux focus. Print magazines on Linux often bundle cover disks that carry software or even complete Linux distributions.[83][84]

Although Linux distributions are generally available without charge, several large corporations sell, support, and contribute to the development of the components of the system and of free software. An analysis of the Linux kernel showed 75 percent of the code from December 2008 to January 2010 was developed by programmers working for corporations, leaving about 18 percent to volunteers and 7% unclassified.[85] Major corporations that provide contributions include Dell, IBM, HP, Oracle, Sun Microsystems (now part of Oracle) and Nokia. A number of corporations, notably Red Hat, Canonical and SUSE, have built a significant business around Linux distributions.

The free software licenses, on which the various software packages of a distribution built on the Linux kernel are based, explicitly accommodate and encourage commercialization; the relationship between a Linux distribution as a whole and individual vendors may be seen as symbiotic. One common business model of commercial suppliers is charging for support, especially for business users. A number of companies also offer a specialized business version of their distribution, which adds proprietary support packages and tools to administer higher numbers of installations or to simplify administrative tasks.

Another business model is to give away the software in order to sell hardware. This used to be the norm in the computer industry, with operating systems such as CP/M, Apple DOS and versions of Mac OS prior to 7.6 freely copyable (but not modifiable). As computer hardware standardized throughout the 1980s, it became more difficult for hardware manufacturers to profit from this tactic, as the OS would run on any manufacturer's computer that shared the same architecture.

Programming on Linux

Most programming languages support Linux either directly or through third-party community based ports.[86] The original development tools used for building both Linux applications and operating system programs are found within the GNU toolchain, which includes the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) and the GNU Build System. Amongst others, GCC provides compilers for Ada, C, C++, Go and Fortran. Many programming languages have a cross-platform reference implementation that supports Linux, for example PHP, Perl, Ruby, Python, Java, Go, Rust and Haskell. First released in 2003, the LLVM project provides an alternative cross-platform open-source compiler for many languages. Proprietary compilers for Linux include the Intel C++ Compiler, Sun Studio, and IBM XL C/C++ Compiler. BASIC in the form of Visual Basic is supported in such forms as Gambas, FreeBASIC, and XBasic, and in terms of terminal programming or QuickBASIC or Turbo BASIC programming in the form of QB64.

A common feature of Unix-like systems, Linux includes traditional specific-purpose programming languages targeted at scripting, text processing and system configuration and management in general. Linux distributions support shell scripts, awk, sed and make. Many programs also have an embedded programming language to support configuring or programming themselves. For example, regular expressions are supported in programs like grep and locate, the traditional Unix MTA Sendmail contains its own Turing complete scripting system, and the advanced text editor GNU Emacs is built around a general purpose Lisp interpreter.

Most distributions also include support for PHP, Perl, Ruby, Python and other dynamic languages. While not as common, Linux also supports C# (via Mono), Vala, and Scheme. Guile Scheme acts as an extension language targeting the GNU system utilities, seeking to make the conventionally small, static, compiled C programs of Unix design rapidly and dynamically extensible via an elegant, functional high-level scripting system; many GNU programs can be compiled with optional Guile bindings to this end. A number of Java Virtual Machines and development kits run on Linux, including the original Sun Microsystems JVM (HotSpot), and IBM's J2SE RE, as well as many open-source projects like Kaffe and JikesRVM.

GNOME and KDE are popular desktop environments and provide a framework for developing applications. These projects are based on the GTK and Qt widget toolkits, respectively, which can also be used independently of the larger framework. Both support a wide variety of languages. There are a number of Integrated development environments available including Anjuta, Code::Blocks, CodeLite, Eclipse, Geany, ActiveState Komodo, KDevelop, Lazarus, MonoDevelop, NetBeans, and Qt Creator, while the long-established editors Vim, nano and Emacs remain popular.[87]

Hardware support

The Linux kernel is a widely ported operating system kernel, available for devices ranging from mobile phones to supercomputers; it runs on a highly diverse range of computer architectures, including the hand-held ARM-based iPAQ and the IBM mainframes System z9 or System z10.[88] Specialized distributions and kernel forks exist for less mainstream architectures; for example, the ELKS kernel fork can run on Intel 8086 or Intel 80286 16-bit microprocessors, while the µClinux kernel fork may run on systems without a memory management unit. The kernel also runs on architectures that were only ever intended to use a manufacturer-created operating system, such as Macintosh computers (with both PowerPC and Intel processors), PDAs, video game consoles, portable music players, and mobile phones.

There are several industry associations and hardware conferences devoted to maintaining and improving support for diverse hardware under Linux, such as FreedomHEC. Over time, support for different hardware has improved in Linux, resulting in any off-the-shelf purchase having a "good chance" of being compatible.[89]

In 2014, a new initiative was launched to automatically collect a database of all tested hardware configurations.[90]

Uses

Besides the Linux distributions designed for general-purpose use on desktops and servers, distributions may be specialized for different purposes including: computer architecture support, embedded systems, stability, security, localization to a specific region or language, targeting of specific user groups, support for real-time applications, or commitment to a given desktop environment. Furthermore, some distributions deliberately include only free software. As of 2015, over four hundred Linux distributions are actively developed, with about a dozen distributions being most popular for general-purpose use.[91]

Desktop

The popularity of Linux on standard desktop computers and laptops has been increasing over the years.[92] Most modern distributions include a graphical user environment, with, as of February 2015, the two most popular environments being the KDE Plasma Desktop and Xfce.[93]

No single official Linux desktop exists: rather desktop environments and Linux distributions select components from a pool of free and open-source software with which they construct a GUI implementing some more or less strict design guide. GNOME, for example, has its human interface guidelines as a design guide, which gives the human–machine interface an important role, not just when doing the graphical design, but also when considering people with disabilities, and even when focusing on security.[94]

The collaborative nature of free software development allows distributed teams to perform language localization of some Linux distributions for use in locales where localizing proprietary systems would not be cost-effective. For example, the Sinhalese language version of the Knoppix distribution became available significantly before Microsoft translated Windows XP into Sinhalese.[95] In this case the Lanka Linux User Group played a major part in developing the localized system by combining the knowledge of university professors, linguists, and local developers.

Performance and applications

The performance of Linux on the desktop has been a controversial topic;[96][97] for example in 2007 Con Kolivas accused the Linux community of favoring performance on servers. He quit Linux kernel development out of frustration with this lack of focus on the desktop, and then gave a "tell all" interview on the topic.[98] Since then a significant amount of development has focused on improving the desktop experience. Projects such as systemd and Upstart (deprecated in 2014) aim for a faster boot time; the Wayland and Mir projects aim at replacing X11 while enhancing desktop performance, security and appearance.[99]

Many popular applications are available for a wide variety of operating systems. For example, Mozilla Firefox, OpenOffice.org/LibreOffice and Blender have downloadable versions for all major operating systems. Furthermore, some applications initially developed for Linux, such as Pidgin, and GIMP, were ported to other operating systems (including Windows and macOS) due to their popularity. In addition, a growing number of proprietary desktop applications are also supported on Linux,[100] such as Autodesk Maya and The Foundry's Nuke in the high-end field of animation and visual effects; see the list of proprietary software for Linux for more details. There are also several companies that have ported their own or other companies' games to Linux, with Linux also being a supported platform on both the popular Steam and Desura digital-distribution services.[101]

Many other types of applications available for Microsoft Windows and macOS also run on Linux. Commonly, either a free software application will exist which does the functions of an application found on another operating system, or that application will have a version that works on Linux, such as with Skype and some video games like Dota 2 and Team Fortress 2. Furthermore, the Wine project provides a Windows compatibility layer to run unmodified Windows applications on Linux. It is sponsored by commercial interests including CodeWeavers, which produces a commercial version of the software. Since 2009, Google has also provided funding to the Wine project.[102][103] CrossOver, a proprietary solution based on the open-source Wine project, supports running Windows versions of Microsoft Office, Intuit applications such as Quicken and QuickBooks, Adobe Photoshop versions through CS2, and many popular games such as World of Warcraft. In other cases, where there is no Linux port of some software in areas such as desktop publishing[104] and professional audio,[105][106][107] there is equivalent software available on Linux. It is also possible to run applications written for Android on other versions of Linux using Anbox.

Components and installation

Besides externally visible components, such as X window managers, a non-obvious but quite central role is played by the programs hosted by freedesktop.org, such as D-Bus or PulseAudio; both major desktop environments (GNOME and KDE) include them, each offering graphical front-ends written using the corresponding toolkit (GTK or Qt). A display server is another component, which for the longest time has been communicating in the X11 display server protocol with its clients; prominent software talking X11 includes the X.Org Server and Xlib. Frustration over the cumbersome X11 core protocol, and especially over its numerous extensions, has led to the creation of a new display server protocol, Wayland.

Installing, updating and removing software in Linux is typically done through the use of package managers such as the Synaptic Package Manager, PackageKit, and Yum Extender. While most major Linux distributions have extensive repositories, often containing tens of thousands of packages, not all the software that can run on Linux is available from the official repositories. Alternatively, users can install packages from unofficial repositories, download pre-compiled packages directly from websites, or compile the source code by themselves. All these methods come with different degrees of difficulty; compiling the source code is in general considered a challenging process for new Linux users, but it is hardly needed in modern distributions and is not a method specific to Linux.

- Samples of graphical desktop interfaces

Cinnamon

Cinnamon Mate

Mate Pantheon

Pantheon

Unity (discontinued; started again 2020 with the release of Ubuntu 20.04)

Unity (discontinued; started again 2020 with the release of Ubuntu 20.04)

Enlightenment

Enlightenment

Sugar

Sugar_R14.0.5_Development.png) Trinity

Trinity

Netbooks

Linux distributions have also become popular in the netbook market, with many devices such as the Asus Eee PC and Acer Aspire One shipping with customized Linux distributions installed.[108]

In 2009, Google announced its Chrome OS as a minimal Linux-based operating system, using the Chrome browser as the main user interface. Chrome OS initially did not run any non-web applications, except for the bundled file manager and media player. A certain level of support for Android applications was added in later versions.[109] As of 2018, Google added the ability to install any Linux software in a container,[110], enabling Chrome OS to be used like any other Linux distribution. Netbooks that shipped with the operating system, termed Chromebooks, started appearing on the market in June 2011.[111]

Servers, mainframes and supercomputers

Linux distributions have long been used as server operating systems, and have risen to prominence in that area; Netcraft reported in September 2006, that eight of the ten (other two with "unknown" OS) most reliable internet hosting companies ran Linux distributions on their web servers,[112] with Linux in the top position. In June 2008, Linux distributions represented five of the top ten, FreeBSD three of ten, and Microsoft two of ten;[113] since February 2010, Linux distributions represented six of the top ten, FreeBSD three of ten, and Microsoft one of ten,[114] with Linux in the top position.

Linux distributions are the cornerstone of the LAMP server-software combination (Linux, Apache, MariaDB/MySQL, Perl/PHP/Python) which has achieved popularity among developers, and which is one of the more common platforms for website hosting.[115]

Linux distributions have become increasingly popular on mainframes, partly due to pricing and the open-source model.[116] In December 2009, computer giant IBM reported that it would predominantly market and sell mainframe-based Enterprise Linux Server.[117] At LinuxCon North America 2015, IBM announced LinuxONE, a series of mainframes specifically designed to run Linux and open-source software.[118][119]

Linux distributions are also dominant as operating systems for supercomputers.[29] As of November 2017, all supercomputers on the 500 list run some variant of Linux.[120]

Smart devices

Several operating systems for smart devices, such as smartphones, tablet computers, home automation (like Google Nest),[30] smart TVs (Samsung and LG Smart TVs use Tizen and WebOS, respectively),[31] and in-vehicle infotainment (IVI) systems[34] (for example Automotive Grade Linux), are based on Linux. Major platforms for such systems include Android, Firefox OS, Mer and Tizen.

Android has become the dominant mobile operating system for smartphones, running on 79.3% of units sold worldwide during the second quarter of 2013.[123] Android is also a popular operating system for tablets, and Android smart TVs and in-vehicle infotainment systems have also appeared in the market.

Although Android is based on a modified version of the Linux kernel, commentators disagree on whether the term "Linux distribution" applies to it, and whether it is "Linux" according to the common usage of the term. Android is a Linux distribution according to the Linux Foundation,[124] Google's open-source chief Chris DiBona,[125] and several journalists.[126][127] Others, such as Google engineer Patrick Brady, say that Android is not Linux in the traditional Unix-like Linux distribution sense; Android does not include the GNU C Library (it uses Bionic as an alternative C library) and some of other components typically found in Linux distributions.[128] Ars Technica wrote that "Although Android is built on top of the Linux kernel, the platform has very little in common with the conventional desktop Linux stack".[128]

Cellphones and PDAs running Linux on open-source platforms became more common from 2007; examples include the Nokia N810, Openmoko's Neo1973, and the Motorola ROKR E8. Continuing the trend, Palm (later acquired by HP) produced a new Linux-derived operating system, webOS, which is built into its line of Palm Pre smartphones.

Nokia's Maemo, one of the earliest mobile operating systems, was based on Debian.[129] It was later merged with Intel's Moblin, another Linux-based operating system, to form MeeGo.[130] The project was later terminated in favor of Tizen, an operating system targeted at mobile devices as well as IVI. Tizen is a project within The Linux Foundation. Several Samsung products are already running Tizen, Samsung Gear 2 being the most significant example.[131] Samsung Z smartphones will use Tizen instead of Android.[132]

As a result of MeeGo's termination, the Mer project forked the MeeGo codebase to create a basis for mobile-oriented operating systems.[133] In July 2012, Jolla announced Sailfish OS, their own mobile operating system built upon Mer technology.

Mozilla's Firefox OS consists of the Linux kernel, a hardware abstraction layer, a web-standards-based runtime environment and user interface, and an integrated web browser.[134]

Canonical has released Ubuntu Touch, aiming to bring convergence to the user experience on this mobile operating system and its desktop counterpart, Ubuntu. The operating system also provides a full Ubuntu desktop when connected to an external monitor.[135]

Embedded devices

Due to its low cost and ease of customization, Linux is often used in embedded systems. In the non-mobile telecommunications equipment sector, the majority of customer-premises equipment (CPE) hardware runs some Linux-based operating system. OpenWrt is a community-driven example upon which many of the OEM firmware releases are based.

For example, the popular TiVo digital video recorder also uses a customized Linux,[136] as do several network firewalls and routers from such makers as Cisco/Linksys. The Korg OASYS, the Korg KRONOS, the Yamaha Motif XS/Motif XF music workstations,[137] Yamaha S90XS/S70XS, Yamaha MOX6/MOX8 synthesizers, Yamaha Motif-Rack XS tone generator module, and Roland RD-700GX digital piano also run Linux. Linux is also used in stage lighting control systems, such as the WholeHogIII console.[138]

Gaming

In the past, there were few games available for Linux. In recent years, more games have been released with support for Linux (especially Indie games), with the exception of a few AAA title games. Android, a popular mobile platform which uses the Linux kernel, has gained much developer interest and is one of the main platforms for mobile game development along with iOS operating system by Apple for iPhone and iPad devices.

On February 14, 2013, Valve released a Linux version of Steam, a popular game distribution platform on PC.[139] Many Steam games were ported to Linux.[140] On December 13, 2013, Valve released SteamOS, a gaming oriented OS based on Debian, for beta testing, and has plans to ship Steam Machines as a gaming and entertainment platform.[141] Valve has also developed VOGL, an OpenGL debugger intended to aid video game development,[142] as well as porting its Source game engine to desktop Linux.[143] As a result of Valve's effort, several prominent games such as DotA 2, Team Fortress 2, Portal, Portal 2 and Left 4 Dead 2 are now natively available on desktop Linux.

On July 31, 2013, Nvidia released Shield as an attempt to use Android as a specialized gaming platform.[144]

Some Linux users play Windows games through Wine or CrossOver Linux.

On August 22, 2018, Valve released their own fork of Wine called Proton, aimed at gaming. It features some improvements over the vanilla Wine such as Vulkan-based DirectX 11 and 12 implementations, Steam integration, better full screen and game controller support and improved performance for multi-threaded games.[145]

Specialized uses

Due to the flexibility, customizability and free and open-source nature of Linux, it becomes possible to highly tune Linux for a specific purpose. There are two main methods for creating a specialized Linux distribution: building from scratch or from a general-purpose distribution as a base. The distributions often used for this purpose include Debian, Fedora, Ubuntu (which is itself based on Debian), Arch Linux, Gentoo, and Slackware. In contrast, Linux distributions built from scratch do not have general-purpose bases; instead, they focus on the JeOS philosophy by including only necessary components and avoiding resource overhead caused by components considered redundant in the distribution's use cases.

Home theater PC

A home theater PC (HTPC) is a PC that is mainly used as an entertainment system, especially a home theater system. It is normally connected to a television, and often an additional audio system.

OpenELEC, a Linux distribution that incorporates the media center software Kodi, is an OS tuned specifically for an HTPC. Having been built from the ground up adhering to the JeOS principle, the OS is very lightweight and very suitable for the confined usage range of an HTPC.

There are also special editions of Linux distributions that include the MythTV media center software, such as Mythbuntu, a special edition of Ubuntu.

Digital security

Kali Linux is a Debian-based Linux distribution designed for digital forensics and penetration testing. It comes preinstalled with several software applications for penetration testing and identifying security exploits.[146] The Ubuntu derivative BackBox provides pre-installed security and network analysis tools for ethical hacking.

The Arch-based BlackArch includes over 2100 tools for pentesting and security researching.[147]

There are many Linux distributions created with privacy, secrecy, network anonymity and information security in mind, including Tails, Tin Hat Linux and Tinfoil Hat Linux. Lightweight Portable Security is a distribution based on Arch Linux and developed by the United States Department of Defense. Tor-ramdisk is a minimal distribution created solely to host the network anonymity software Tor.

System rescue

Linux Live CD sessions have long been used as a tool for recovering data from a broken computer system and for repairing the system. Building upon that idea, several Linux distributions tailored for this purpose have emerged, most of which use GParted as a partition editor, with additional data recovery and system repair software:

- GParted Live – a Debian-based distribution developed by the GParted project.

- Parted Magic – a commercial Linux distribution.

- SystemRescueCD – an Arch-based distribution with support for editing Windows registry.

In space

SpaceX uses multiple redundant flight computers in a fault-tolerant design in its Falcon 9 rocket. Each Merlin engine is controlled by three voting computers, with two physical processors per computer that constantly check each other's operation. Linux is not inherently fault-tolerant (no operating system is, as it is a function of the whole system including the hardware), but the flight computer software makes it so for its purpose.[148] For flexibility, commercial off-the-shelf parts and system-wide "radiation-tolerant" design are used instead of radiation hardened parts.[148] As of July 2019, SpaceX has conducted over 76 launches of the Falcon 9 since 2010, out of which all but one have successfully delivered their primary payloads to the intended orbit, and has used it to transport astronauts to the International Space Station. The Dragon 2 crew capsule also uses Linux in conjuntion with Chromium OS for its user interface.[36]

Windows was deployed as the operating system on non-mission critical laptops used on the space station, but it was later replaced with Linux. Robonaut 2, the first humanoid robot in space, is also Linux-based.[149]

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory has used Linux for a number of years "to help with projects relating to the construction of unmanned space flight and deep space exploration"; NASA uses Linux in robotics in the Mars rover, and Ubuntu Linux to "save data from satellites".[150]

Education

Linux distributions have been created to provide hands-on experience with coding and source code to students, on devices such as the Raspberry Pi. In addition to producing a practical device, the intention is to show students "how things work under the hood".[151]

The Ubuntu derivatives Edubuntu and The Linux Schools Project, as well as the Debian derivative Skolelinux, provide education-oriented software packages. They also include tools for administering and building school computer labs and computer-based classrooms, such as the Linux Terminal Server Project (LTSP).

Others

Instant WebKiosk and Webconverger are browser-based Linux distributions often used in web kiosks and digital signage. Thinstation is a minimalist distribution designed for thin clients. Rocks Cluster Distribution is tailored for high-performance computing clusters.

There are general-purpose Linux distributions that target a specific audience, such as users of a specific language or geographical area. Such examples include Ubuntu Kylin for Chinese language users and BlankOn targeted at Indonesians. Profession-specific distributions include Ubuntu Studio for media creation and DNALinux for bioinformatics. There is also a Muslim-oriented distribution of the name Sabily that consequently also provides some Islamic tools. Certain organizations use slightly specialized Linux distributions internally, including GendBuntu used by the French National Gendarmerie, Goobuntu used internally by Google, and Astra Linux developed specifically for the Russian army.

Market share and uptake

Many quantitative studies of free/open-source software focus on topics including market share and reliability, with numerous studies specifically examining Linux.[152] The Linux market is growing rapidly, and the revenue of servers, desktops, and packaged software running Linux was expected to exceed $35.7 billion by 2008.[153] Analysts and proponents attribute the relative success of Linux to its security, reliability, low cost, and freedom from vendor lock-in.[154][155]

- Desktops and laptops

- According to web server statistics, (that is, based on the numbers recorded from visits to websites by client devices,) as of November 2018, the estimated market share of Linux on desktop computers is around 2.1%. In comparison, Microsoft Windows has a market share of around 87%, while macOS covers around 9.7%.

- Web servers

- W3Cook publishes stats that use the top 1,000,000 Alexa domains,[156] which as of May 2015 estimate that 96.55% of web servers run Linux, 1.73% run Windows, and 1.72% run FreeBSD.[157]

- W3Techs publishes stats that use the top 10,000,000 Alexa domains, updated monthly[158] and as of November 2016 estimate that 66.7% of web servers run Linux/Unix, and 33.4% run Microsoft Windows.[159]

- In September 2008, Microsoft's then-CEO Steve Ballmer stated that 60% of web servers ran Linux, versus 40% that ran Windows Server.[160]

- IDC's Q1 2007 report indicated that Linux held 12.7% of the overall server market at that time;[161] this estimate was based on the number of Linux servers sold by various companies, and did not include server hardware purchased separately that had Linux installed on it later.

- Mobile devices

- Android, which is based on the Linux kernel, has become the dominant operating system for smartphones. During the second quarter of 2013, 79.3% of smartphones sold worldwide used Android.[123] Android is also a popular operating system for tablets, being responsible for more than 60% of tablet sales as of 2013.[162] According to web server statistics, as of December 2014 Android has a market share of about 46%, with iOS holding 45%, and the remaining 9% attributed to various niche platforms.[163]

- Film production

- For years Linux has been the platform of choice in the film industry. The first major film produced on Linux servers was 1997's Titanic.[164][165] Since then major studios including DreamWorks Animation, Pixar, Weta Digital, and Industrial Light & Magic have migrated to Linux.[166][167][168] According to the Linux Movies Group, more than 95% of the servers and desktops at large animation and visual effects companies use Linux.[169]

- Use in government

- Linux distributions have also gained popularity with various local and national governments. The federal government of Brazil is well known for its support for Linux.[170][171] News of the Russian military creating its own Linux distribution has also surfaced, and has come to fruition as the G.H.ost Project.[172] The Indian state of Kerala has gone to the extent of mandating that all state high schools run Linux on their computers.[173][174] China uses Linux exclusively as the operating system for its Loongson processor family to achieve technology independence.[175] In Spain, some regions have developed their own Linux distributions, which are widely used in education and official institutions, like gnuLinEx in Extremadura and Guadalinex in Andalusia. France and Germany have also taken steps toward the adoption of Linux.[176] North Korea's Red Star OS, developed since 2002, is based on a version of Fedora Linux.[177]

Copyright, trademark, and naming

Linux kernel is licensed under the GNU General Public License (GPL), version 2. The GPL requires that anyone who distributes software based on source code under this license, must make the originating source code (and any modifications) available to the recipient under the same terms.[178] Other key components of a typical Linux distribution are also mainly licensed under the GPL, but they may use other licenses; many libraries use the GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL), a more permissive variant of the GPL, and the X.Org implementation of the X Window System uses the MIT License.

Torvalds states that the Linux kernel will not move from version 2 of the GPL to version 3.[179][180] He specifically dislikes some provisions in the new license which prohibit the use of the software in digital rights management.[181] It would also be impractical to obtain permission from all the copyright holders, who number in the thousands.[182]

A 2001 study of Red Hat Linux 7.1 found that this distribution contained 30 million source lines of code.[183] Using the Constructive Cost Model, the study estimated that this distribution required about eight thousand person-years of development time. According to the study, if all this software had been developed by conventional proprietary means, it would have cost about $1.6 billion (2020 US dollars) to develop in the United States.[183] Most of the source code (71%) was written in the C programming language, but many other languages were used, including C++, Lisp, assembly language, Perl, Python, Fortran, and various shell scripting languages. Slightly over half of all lines of code were licensed under the GPL. The Linux kernel itself was 2.4 million lines of code, or 8% of the total.[183]

In a later study, the same analysis was performed for Debian version 4.0 (etch, which was released in 2007).[184] This distribution contained close to 283 million source lines of code, and the study estimated that it would have required about seventy three thousand man-years and cost US$8.84 billion (in 2020 dollars) to develop by conventional means.

In the United States, the name Linux is a trademark registered to Linus Torvalds.[8] Initially, nobody registered it, but on August 15, 1994, William R. Della Croce, Jr. filed for the trademark Linux, and then demanded royalties from Linux distributors. In 1996, Torvalds and some affected organizations sued him to have the trademark assigned to Torvalds, and, in 1997, the case was settled.[186] The licensing of the trademark has since been handled by the Linux Mark Institute (LMI). Torvalds has stated that he trademarked the name only to prevent someone else from using it. LMI originally charged a nominal sublicensing fee for use of the Linux name as part of trademarks,[187] but later changed this in favor of offering a free, perpetual worldwide sublicense.[188]

The Free Software Foundation (FSF) prefers GNU/Linux as the name when referring to the operating system as a whole, because it considers Linux distributions to be variants of the GNU operating system initiated in 1983 by Richard Stallman, president of the FSF.[14][15] They explicitly take no issue over the name Android for the Android OS, which is also an operating system based on the Linux kernel, as GNU is not a part of it.

A minority of public figures and software projects other than Stallman and the FSF, notably Debian (which had been sponsored by the FSF up to 1996),[189] also use GNU/Linux when referring to the operating system as a whole.[136][190][191] Most media and common usage, however, refers to this family of operating systems simply as Linux, as do many large Linux distributions (for example, SUSE Linux and Red Hat Enterprise Linux). By contrast, Linux distributions containing only free software use "GNU/Linux" or simply "GNU", such as Trisquel GNU/Linux, Parabola GNU/Linux-libre, BLAG Linux and GNU, and gNewSense.

As of May 2011, about 8% to 13% of a modern Linux distribution is made of GNU components (the range depending on whether GNOME is considered part of GNU), as determined by counting lines of source code making up Ubuntu's "Natty" release; meanwhile, 6% is taken by the Linux kernel, increased to 9% when including its direct dependencies.[192]

See also

- Comparison of Linux distributions

- Comparison of open source and closed source

- Comparison of operating systems

- Comparison of X Window System desktop environments

- Criticism of Linux

- Linux Documentation Project

- Linux Foundation

- Linux From Scratch

- Linux Software Map

- List of Linux distributions

- List of games released on Linux

- List of operating systems

- Loadable kernel module

- Usage share of operating systems

Notes

- GNU is the primary userland used in nearly all Linux distributions.[2][3][4] The GNU userland contains system daemons, user applications, the GUI, and various libraries. GNU Core utilities are an essential part of most distributions. Most Linux distributions use the X Window system.[5] Other components of the userland, such as the widget toolkit, vary with the specific distribution, desktop environment, and user configuration.[6]

- "Linux" trademark is owned by Linus Torvalds[8] and administered by the Linux Mark Institute.

References

- Linux Online (2008). "Linux Logos and Mascots". Archived from the original on August 15, 2010. Retrieved August 11, 2009.

- "GNU Userland". Archived from the original on March 8, 2016.

- "Unix Fundamentals — System Administration for Cyborgs". Archived from the original on October 5, 2016.

- "Operating Systems — Introduction to Information and Communication Technology". Archived from the original on February 21, 2016.

- "The X Window System". Archived from the original on January 20, 2016.

- "PCLinuxOS Magazine - HTML". Archived from the original on May 15, 2013.

- "The Linux Kernel Archives: Frequently asked questions". kernel.org. September 2, 2014. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Reg No: 1916230". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2006.

- "Re: How to pronounce Linux?". Newsgroup: comp.os.linux. April 23, 1992. Usenet: 1992Apr23.123216.22024@klaava.Helsinki.FI. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- Eckert, Jason W. (2012). Linux+ Guide to Linux Certification (Third ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Cengage Learning. p. 33. ISBN 978-1111541538. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

The shared commonality of the kernel is what defines a system's membership in the Linux family; the differing OSS applications that can interact with the common kernel are what differentiate Linux distributions.

- "Twenty Years of Linux according to Linus Torvalds". ZDNet. April 13, 2011. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- Linus Benedict Torvalds (October 5, 1991). "Free minix-like kernel sources for 386-AT". Newsgroup: comp.os.minix. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- "What Is Linux: An Overview of the Linux Operating System". Medium. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- "GNU/Linux FAQ". Gnu.org. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- "Linux and the GNU System". Gnu.org. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- DistroWatch. "DistroWatch.com: Put the fun back into computing. Use Linux, BSD". distrowatch.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- Bhartiya, Swapnil. "Best Linux distros of 2016: Something for everyone". CIO. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- "10 Top Most Popular Linux Distributions of 2016". www.tecmint.com. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- "What is Linux?". Opensource.com. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Barry Levine (August 26, 2013). "Linux' 22th [sic] Birthday Is Commemorated - Subtly - by Creator". Simpler Media Group, Inc. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

Originally developed for Intel x86-based PCs, Torvalds' "hobby" has now been released for more hardware platforms than any other OS in history.

- Linux Devices (November 28, 2006). "Trolltech rolls "complete" Linux smartphone stack". Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- "os-ww-monthly-201510-201510-bar". Archived from the original on November 23, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

- Steven J. Vaughan-Nichols. "Chromebook shipments leap by 67 percent". ZDNet. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- "OS Market Share and Usage Trends". W3Cook.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2015.

- Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (2017). "Linux totally dominates supercomputers". ZDNet (published November 14, 2017). Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- Thibodeau, Patrick (2009). "IBM's newest mainframe is all Linux". Computerworld (published December 9, 2009). Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- Lyons, Daniel (March 15, 2005). "Linux rules supercomputers". Forbes. Archived from the original on February 24, 2007. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- "Nest Learning Thermostat open source compliance". Nest.com. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- Eric Brown (March 29, 2019). "Linux continues advance in smart TV market". linuxgizmos.com. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Sony Open Source Code Distribution Service". Sony Electronics. Archived from the original on October 4, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- "Sharp Liquid Crystal Television Instruction Manual" (PDF). Sharp Electronics. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- Steven J. Vaughan-Nichols (January 4, 2019). "It's a Linux-powered car world". ZDNet. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- IBM (October 2001). "Linux Watch (WatchPad)". Archived from the original on June 18, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- "From Earth to orbit with Linux and SpaceX | ZDNet". www.zdnet.com.

- Ritchie, D.M. (October 1984), "The UNIX System: The Evolution of the UNIX Time-sharing System", AT&T Bell Laboratories Technical Journal, 63 (8): 1577, doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1984.tb00054.x,

However, UNIX was born in 1969 ...

- Meeker, Heather (September 21, 2017). "Open source licensing: What every technologist should know". Opensource.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- "About the GNU Project – Initial Announcement". Gnu.org. June 23, 2008. Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- Christopher Tozzi (August 23, 2016). "Open Source History: Why Did Linux Succeed?". Archived from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- "Linus vs. Tanenbaum debate". Archived from the original on October 3, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- Linksvayer, Mike (1993). "The Choice of a GNU Generation – An Interview With Linus Torvalds". Meta magazine. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- "MINIX is now available under the BSD license" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, April 9, 2000, minix1.woodhull.com

- Torvalds, Linus. "What would you like to see most in minix?". Newsgroup: comp.os.minix. Usenet: 1991Aug25.205708.9541@klaava.Helsinki.FI. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- Linus Torvalds (October 14, 1992). "Chicken and egg: How was the first linux gcc binary created??". Newsgroup: comp.os.minix. Usenet: 1992Oct12.100843.26287@klaava.Helsinki.FI. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- Torvalds, Linus (January 5, 1992). "Release notes for Linux v0.12". Linux Kernel Archives. Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

The Linux copyright will change: I've had a couple of requests to make it compatible with the GNU copyleft, removing the “you may not distribute it for money” condition. I agree. I propose that the copyright be changed so that it confirms to GNU ─ pending approval of the persons who have helped write code. I assume this is going to be no problem for anybody: If you have grievances ("I wrote that code assuming the copyright would stay the same") mail me. Otherwise, The GNU copyleft takes effect since the first of February. If you do not know the gist of the GNU copyright ─ read it.

- "Overview of the GNU System". Gnu.org. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- Torvalds, Linus and Diamond, David, Just for Fun: The Story of an Accidental Revolutionary, 2001, ISBN 0-06-662072-4

- Torvalds, Linus (March 1994). "Index of /pub/linux/kernel/SillySounds". Archived from the original on October 8, 2009. Retrieved August 3, 2009.

- Garfinkel, Simson; Spafford, Gene; Schwartz, Alan (2003). Practical UNIX and Internet Security. O'Reilly. p. 21.

- Santhanam, Anand; Vishal Kulkarni (March 1, 2002). "Linux system development on an embedded device". DeveloperWorks. IBM. Archived from the original on March 29, 2007. Retrieved July 26, 2007.

- Galli, Peter (August 8, 2007). "Vista Aiding Linux Desktop, Strategist Says". eWEEK. Ziff Davis Enterprise Inc. Archived from the original on July 9, 2009. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- Paul, Ryan (September 3, 2007). "Linux market share set to surpass Win 98, OS X still ahead of Vista". Ars Technica. Ars Technica, LLC. Archived from the original on November 16, 2007. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- Beer, Stan (January 23, 2007). "Vista to play second fiddle to XP until 2009: Gartner". iTWire. iTWire. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- "Operating System Marketshare for Year 2007". Market Share. Net Applications. November 19, 2007. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- "Vista slowly continues its growth; Linux more aggressive than Mac OS during the summer". XiTiMonitor. AT Internet/XiTi.com. September 24, 2007. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- "Global Web Stats". W3Counter. Awio Web Services LLC. November 10, 2007. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- "June 2004 Zeitgeist". Google Press Center. Google Inc. August 12, 2004. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- McMillan, Robert. "IBM, Brazilian government launch Linux effort". www.infoworld.com. IDG News Service. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- "About Us - The Linux Foundation". Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "The Free Software Foundation Management". Archived from the original on November 11, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- "Free software is a matter of liberty, not price — Free Software Foundation — working together for free software". Fsf.org. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- Email correspondence on the Linux Kernel development mailing list Linus Torvalds (November 30, 2001). "Re: Coding style, a non-issue". kernel.org.

- Raymond, Eric S. (2001). O’Reilly, Tim (ed.). The Cathedral and the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary (Second edition ed.). O’Reilly & Associates. p. 16. ISBN 0-596-00108-8.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- "You have to design it you cannot asymptotically reach Security." Cantrill 2017

- Interview with Allan Jude, FreeBSD developer https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ya6h2zKlpaQ&feature=youtu.be&t=4138

- "Why is Linux called a monolithic kernel?". stackoverflow.com. 2009. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- "Anatomy of a Linux System" (PDF). O'Reilly. July 23–26, 2001. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- M. Tim Jones (May 31, 2006). "Inside the Linux boot process". IBM Developer Works. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- Jake Edge (June 8, 2013). "The Wayland Situation: Facts About X vs. Wayland (Phoronix)". LWN.net. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- "Linux TV: Television with Linux". linuxtv.org. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- Jonathan Corbet (October 11, 2006). "The Video4Linux2 API: an introduction". LWN.net. Archived from the original on October 7, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- "Part I. Video for Linux Two API Specification". Chapter 7. Changes. linuxtv.org. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- "gnu.org". www.gnu.org. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "POSIX.1 (FIPS 151-2) Certification". Archived from the original on February 26, 2012.

- "How source code compatible is Debian with other Unix systems?". Debian FAQ. the Debian project. Archived from the original on October 16, 2011.

- Eissfeldt, Heiko (August 1, 1996). "Certifying Linux". Linux Journal. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016.

- "The Debian GNU/Linux FAQ – Compatibility issues". Archived from the original on October 10, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- comments, 26 Jul 2018 Steve OvensFeed 151up 9. "The evolution of package managers". Opensource.com. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "Get Fedora". getfedora.org. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- design, Cynthia Sanchez: front-end and UI, Zvezdana Marjanovic: graphic. "The makers' choice for sysadmins, developers and desktop users". openSUSE. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- Linux Format. "Linux Format DVD contents". Archived from the original on August 8, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- linux-magazine.com. "Current Issue". Archived from the original on January 10, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- "75% of Linux code now written by paid developers". APC. Archived from the original on January 22, 2010. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- "gfortran — the GNU Fortran compiler, part of GCC". GNU GCC. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- Brockmeier, Joe. "A survey of Linux Web development tools". Archived from the original on October 19, 2006. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

- Advani, Prakash (February 8, 2004). "If I could re-write Linux". freeos.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- Bruce Byfield (August 14, 2007). "Is my hardware Linux-compatible? Find out here". Linux.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- "Linux Hardware". Linux Hardware Project. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- "The LWN.net Linux Distribution List". LWN.net. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- What is Linux. Archived at Wayback Engine. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- "Survey says: KDE Plasma is the most popular desktop Linux environment". Archived from the original on January 6, 2016.

- Nathan Willis (August 14, 2013). "Prompt-free security for GNOME". LWN.net. Archived from the original on October 7, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- "Introducing sinhala linux". Archived from the original on November 24, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

- Steven J. Vaughan-Nichols (November 13, 2018). "The Linux desktop: With great success comes great failure". Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Steven J. Vaughan-Nichols for Linux and Open Source (April 8, 2018). "The Linux desktop is in trouble". Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- "Why I quit: kernel developer Con Kolivas". APC Magazine. ACP Magazines. July 24, 2007. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- "Wayland Architecture". freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- "The Global Desktop Project, Building Technology and Communities". Archived from the original on April 26, 2006. Retrieved May 7, 2006.

- Dawe, Liam (January 1, 2013). "A 2012 review and what's in store for 2013?". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- Kegel, Dan (February 14, 2008). "Google's support for Wine in 2007". wine-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- "Open Source Patches: Wine". Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Advani, Prakash (October 27, 2000). "Microsoft Office for Linux?". FreeOS. FreeOS Technologies (I) Pvt. Ltd. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- Smith-Heisters, Ian (October 11, 2005). "Editing audio in Linux". Ars Technica. Ars Technica, LLC. Archived from the original on February 17, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- Lumma, Carl (April 2007). "Linux: It's Not Just For Computer Geeks Anymore". Keyboard Magazine. New Bay Media, LLC. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- James, Daniel (February 2004). "Using Linux For Recording & Mastering". Sound On Sound. SOS Publications Group. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- Schofield, Jack (May 28, 2009). "Are netbooks losing their shine?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on December 21, 2013. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- "Introducing the Google Chrome OS". Official Google Blog. Blogger. July 7, 2009. Archived from the original on April 10, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- Set up Linux on Chromebook

- Stein, Scott (May 11, 2011). "First Take: Samsung Series 5 Chromebook, the future of Netbooks?". Journal. CNET. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Rackspace Most Reliable Hoster in September". Netcraft. October 7, 2006. Archived from the original on November 6, 2006. Retrieved November 1, 2006.

- "Aplus.Net is the Most Reliable Hosting Company Site in June 2008". Netcraft. July 7, 2008. Archived from the original on July 27, 2008. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- "Most Reliable Hosting Company Sites in February 2010". Netcraft. March 1, 2010. Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- SecuritySpace (June 1, 2010). "Web Server Survey". SecuritySpace. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- Danner, David (April 3, 2012). "How CIOs Can Use Linux on the Mainframe to Maximize Savings and Lower TCO". Enterprise Executive. Enterprise Systems Media. Archived from the original on July 8, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- Timothy Prickett Morgan (December 11, 2009). "IBM punts Linux-only mainframes Big MIPS, deep discounts". The Register. Archived from the original on December 13, 2009. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- Babcock, Charles (August 18, 2015). "IBM's LinuxONE Mainframe: What's Old Is New Again". InformationWeek. InformationWeek. Archived from the original on July 8, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- Hoffman, Dale; Mitran, Marcel (August 17, 2015). "Open Source & ISV Ecosystem Enablement for LinuxONE and IBM z" (PDF). Linux Foundation. IBM. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites: Operating system Family / Linux". Top500.org. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- "Tesla Model S Ethernet Network Explored". Archived from the original on April 9, 2014.

- "Tesla Model S owners hack their cars, find Ubuntu". Autoblog. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- "Android Nears 80% Market Share In Global Smartphone Shipments, As iOS And BlackBerry Share Slides, Per IDC". Archived from the original on July 5, 2017.

- McPherson, Amanda (December 13, 2012). "What a Year for Linux: Please Join us in Celebration". Linux Foundation. Archived from the original on April 17, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- Proschofsky, Andreas (July 10, 2011). "Google: "Android is the Linux desktop dream come true"". derStandard.at. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- Hildenbrand, Jerry (November 8, 2012). "Ask AC: Is Android Linux?". Android Central. Mobile Nations. Archived from the original on April 8, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- Lynch, Jim (August 20, 2013). "Is Android really a Linux distribution?". ITworld. Archived from the original on February 5, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- Paul, Ryan (February 24, 2009). "Dream(sheep++): A developer's introduction to Google Android". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- "Chapter 3 - maemo Platform Overview". Wayback Machine. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- Grabham, Dan (February 15, 2010). "Inter and Nokia merge Moblin and Maemo to form MeeGo". Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- Whitwam, Ryan (February 22, 2014). "Samsung Announces Gear 2 and Gear 2 Neo Smart Watches Running Tizen, Available Worldwide In April". Archived from the original on May 4, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- Gibbs, Samuel (June 2, 2014). "Samsung Z smartphone ditches Android for Tizen software". Archived from the original on June 12, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Mer Project". Mer Project. Archived from the original on May 30, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Firefox OS architecture". Mozilla Developer Network. Mozilla. Archived from the original on June 4, 2014. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- "App ecosystem". Ubuntu. Canonical Ltd. Archived from the original on June 13, 2014. Retrieved June 13, 2014.