Hohengeroldseck

Hohengeroldseck was a state of the Holy Roman Empire. It was founded by the House of Geroldseck, a German noble family which arrived in the Ortenau region of Swabia reputedly in 948, though the first mention of the family is documented in the 1080s. The family line went extinct in 1634 and was succeeded by the Kronberg and Leyen families. In 1806, the county was raised to a Principality and adopted the family name of Leyen. Late in 1813, the Principality was mediatized by Austria and its name reverted to Hohengeroldseck, but the history of the state ended when Austria ceded it to the Grand Duchy of Baden in 1819 and merged with the district of Lahr in 1831.

The Geroldseck Family

%2C_Burgruine_Hohengeroldseck%2CBlick_von_S%C3%BCden_01.11.2016_1.jpg)

Originating in Alsace during the Carolingian and Ottonian periods, the Geroldsecks were first mentioned in a witness list dating from the 1080s, and were definitely proven to reside in the Black Forest region from 1139. They were heavily involved in mining of ores, especially silver.[1] The Hohengeroldseck family supported and rebuilt many monasteries within the Zähringen domains, notably Schuttern and Ettenheimmünster, each located about 25 kilometers from castle Hohengeroldseck. All together, the Geroldsecks founded between 16 and 20 monasteries within the southern half of modern Baden. They were closely aligned with the Bishop of Strassburg, being Vogt protectors for nearly 371 years, and twice Bishops of Strassburg, 1262–1273. Their family seat was Castle Hohengeroldseck near Biberach. [2] Walter of Geroldseck built the Castle upon the Schönberg between 1240 and 1250.

Around 1252, the family inherited the most important portions of the County of Sulz on the Neckar as well as the dominions of Schenkenzell and Lossburg and perhaps Romberg, and these formed the basis of their Lordship.[3]

In 1260, Walter of Geroldseck became Bishop of Strassburg. His brother Hermann obtained a bailiwick lying between Seltz and the Bishopric of Basel, and incurred the wrath of the latter when he seized the monastery of St. Gregory in the Alsatian Münstertal. Walter lent aid to his brother, which irritated the townspeople of Strassburg. Further attempts to assert his authority over the townspeople caused a revolt, and he was driven from the city. Walter found many allies to assist him in attempting to reclaim the city, including the Bishop of Trier, but he was defeated in the Battle of Hausbergen in 1262, and henceforth Strassburg was a free Imperial City.

In 1270, Baron Heinrich of Geroldseck married Agnes the heiress of the last Count of Veldenz and so founded the second dynasty of that territory. In 1277, the house of Geroldseck divided into Upper (Hohen-) and Lower lines, sharing some common properties such as the bailiwicks of Friesenheim and Oberschopfheim, the village Ottenheim, as well as Castle Schwanau on the Alsatian side of the Rhine. A further division of the Hohen-Geroldseck line in the beginning of the fourteenth century caused the independence of the Veldenz Counts as well as the loss of old territories in Alsace.

A different Castle Geroldseck was built in the thirteenth century on lands of the Lower Line in what is today the commune of Niederstinzel in the Wasgau region of Alsace. Hans of Geroldseck ruled from the castle as a fief of the Bishop of Metz from 1355 until his death in 1391, after which time his rights devolved to the Lords of Ochsenstein and the counts of Zweibrücken-Bitsch. Castle Geroldseck itself was destroyed by fire in 1381. Old German folktales regarded the ruins as the meeting place of great heroes, such as Ariovistus, Herman, Widukind, and Siegfried. Legends claimed that, when the Germans would be in the greatest need, these heroes would come out from the castle to help them.[4]

The Lower Line ruled its Swabian territory situated upon the city of Lahr until 1426, when the family went extinct. Baron Diebold of Hohen-Geroldseck therefore challenged the legitimate heirs, the Counts of Moers-Saarwerden, for the inheritance in 1428, but could not prevail and suffered grave economic woes.

Baron Dietrich of Hohen-Geroldseck played an ambitious role in the quarrel between Austria and the Electoral Palatinate in the 1480s, but this led to the outright conquest of Castle Geroldseck by the Palatinate in 1486. The defeat of the Elector in the Landshut Succession War in 1504 saw the return of the family to their seat.

According to the Imperial Matriculation of 1521, the Lordship of Hohengeroldseck contributed 1 cavalryman and 3 infantrymen to the Imperial Army. In 1545 and 1551 it contributed 1 cavalryman, 2 infantrymen, and 20 Florins in money. In case of emergency, a further 16 Florins was to be paid to the Army. In addition, Hohengeroldseck had to pay to the Imperial Court Chamber annually 10 Reichsthalers and 12 1/2 Kreutzer. These contribution rates remained unchanged until the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved in 1806.[5]

Elisabeth of Hohen-Geroldseck was elected to rule the Imperial Abbey of Buchau on May 28, 1523. The Abbey was a member of the Swabian League. Elisabeth had to flee in 1525 when the Peasant's War saw the League's enemies attack the Abbey. She returned shortly thereafter and completed fortifications and many building extensions. Elisabeth died in 1540.

The last of the House of Geroldseck was Baron Jacob, who began his reign in 1584. In that year, Jacob began construction of a three-storey residence in the middle of the walled enclosure of the water castle of Dautenstein in Seelbach. He moved out of Castle Hohengeroldseck in 1599 and took up residence in the Dautenstein in that same year.

Baron Jacob died in the year 1634. His daughter and heiress, Anna Maria, first married Count Frederick of Solms-Laubach, founder of the Rödelheim branch of the family. After his death, reported in places as 1649 but likely much earlier, his widow Anna Maria wed Margrave Frederick V of Baden-Durlach on 13 February 1644.

The Kronberg Family

Previously in the year 1620, the Baron of Kronberg had obtained rights to the Lordship of Hohengeroldseck as an Austrian fief in the event Baron Jacob's line went extinct. He took possession in 1635, at the same time being raised to a Count. Anna Maria petitioned the Emperor but could not receive her proper inheritance. The Counts of Kronberg never resided in Hohengeroldseck but at their ancient residence in Kronberg im Taunus.

In 1636, the Dautenstein was destroyed as a casualty of the Thirty Years' War and rebuilt shortly thereafter, though on a more modest scale.

The castle of Hohengeroldseck itself was destroyed by the French in 1689, a casualty of the War of the Palatinate. The destruction has been uniformly but erroneously attributed by 19th century authors to the actions of Marshal Crequi, who actually died in 1687, two years before the castle was laid waste.

In 1697, the Margraves of Baden seized Hohengeroldseck as allies of the French, but the Imperial Army drove them out soon after.

In 1704, Count John Nicholas died, and with him the Kronberg family went extinct. Of the Kronberg lands, the dominion of Rothenberg was disbursed to the Count of Degenfeld and Kronberg itself to the Elector of Mainz. Hohengeroldseck was granted to Count Karl Caspar von der Leyen.

The Leyen Family

In 1711, Count Karl Caspar von der Leyen was created Imperial Count which guaranteed sovereignty through Imperial immediacy.

Renovations to Castle Dautenstein in the second half of the 18th Century saw the removal of its walls, rendering its appearance similar to a large farmhouse, but the compound retained its original footprint, and the building served as a modest court for the Counts of Leyen whenever they might journey from their residential palace at Blieskastel.

However, on May 14, 1793, the French Revolutionary Army surrounded Blieskastel Palace, forcing the Leyen family to flee. Having lost all of their possessions on the left bank of the Rhine river, the nearly destitute family took up residence in the Dautenstein, where they remained until the end of their rule over Hohengeroldseck.

The peace treaty with France denied the family restoration of their lands, and numerous petitions to the Imperial Diet for compensation were fruitless, as the Final Recess of 1803 denied the family compensation granted other exiled nobles on the basis that the Leyen family did nothing to aid the war against France. Henceforth, Count Philip Francis looked to France for friendship. The Friendship paid off in that Hohengeroldseck was spared the mediatization of 1806 that consumed much larger and wealthier states by virtue that the Count was nephew to Archchancellor Karl Theodor von Dalberg,[6] a close collaborator of Napoleon's.

After the Holy Roman Empire

The County joined the Rhine Confederation as a founding member on July 12, 1806. Article V. of the Treaty of the Confederation of the Rhine raised Count Philip Francis to a Prince, and his realm became known as the Principality of Leyen. The same treaty declared Leyen separated forevermore from the Holy Roman Empire, as per Article III. The Empire itself was declared at an end on August 6, 1806. As for the army, Article XXXVIII. of the Rhine Treaty decreed a 4,000 strong combined army corps raised by "the other Princes of the Confederation," to which the Prince of Leyen had to supply a contingent of 29 soldiers and the money to equip and care for them.[7]

The outbreak of the War of the Sixth Coalition in 1813 signaled the approaching end of the French supremacy. The Battle of the Nations in mid-October removed France's grip on Germany, and the members of the Rhine Confederation either abandoned their French alliance or were overrun by the advancing Allies. On December 13, 1813, the Principality of Leyen was occupied by Austrian forces, declared "leaderless" because Prince Philip was residing in Paris at the time, and formally mediatized.

Later History

Hohengeroldseck was awarded to Austria by the Congress of Vienna in 1815. Its cession to Baden was brought about in a very complex way. At the Congress of Vienna, Austria insisted on the re-annexation of Salzburg, which had been made over to Bavaria by Napoleon after the Treaty of Schönbrunn in 1809. In the Treaty of Munich in 1816, Austria and Bavaria came to terms, with the Austrians promising to support Bavaria in its ambition to secure the County of Sponheim from Prussia and Baden's portion of the Palatinate on the right bank of the Rhine River following the death of the childless Grand Duke Charles of Baden.

At the Congress of Aix-la-Chappelle in 1818, however, the great powers came to terms with Grand Duke Charles' succession, and guaranteed his successor a full inheritance. To help meet its obligations to Bavaria, Austria proposed to cede Hohengeroldseck to Baden in exchange for Baden's transfer of that portion of Wertheim on the opposite side of the River Main (the town of Steinfeld and surrounding territory) to Bavaria. All parties accepted.[8]

On July 10, 1819, the Frankfurt Convention was held to solve all outstanding German border issues. The Convention confirmed all decisions made at the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle. Austria exchanged Hohengeroldseck for Steinfeld, which in turn was ceded to Bavaria, the protocols for the latter transfer being signed in Aschaffenburg on October 27, 1819.

The Baden authorities referred to the territory as "the Provisional District of Hohengeroldseck" until March 1, 1831, when it was merged into the District of Lahr and henceforth disappeared from history.[9]

Geographic Disposition of the State

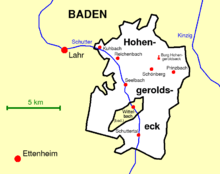

Located in the Ortenau region of Swabia, the area of the state never exceeded 45 square miles. Despite its small size, Hohengeroldseck had many neighbors. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, it was bound clockwise by the Free Imperial City of Zell to the north, the Lordship of Hausen (a possession of the Prince of Fürstenberg) to the east, the Ettenheim territory of the bishopric of Strassburg to the south as well as an enclave within the territory of Hohengeroldseck itself, an estate of a Free Imperial Knight of the autonomous Ortenau District to the southwest, territory of Nassau-Usingen to the west with portions of Baden-Durlach above and below it, and finally a tiny exclave of Further Austria to the northwest.

In addition, two small exclaves to the northwest of Hohengeroldseck shared numerous borders. The larger exclave was surrounded on three sides by three different estates of Free Imperial Knights of the Ortenau District, with an exclave of Further Austria to the north and the Free Imperial City of Gengenbach to the northeast, while the smaller exclave of Hohengeroldseck was bound to the south by the Schutterwald knightly estate (held in condominium with Austria), another exclave of Further Austria to the west, and the Free Imperial City of Offenburg to the north and east. Both exclaves were held in condominium with Austria.[10]

See also

References

- Fickler, Carl Borromeo Alois: Brief History of the houses Fürstenberg, Geroldseck und von der Leyen / Carl B. Fickler. - Karlsruhe: Macklot, 1844. - 112 S.; (dt.) - 112 S.

- Gabbert, Carsten: Die Geroldsecker und ihre Burgen Geroldseck und Hohengeroldseck : das Verhältnis des Geschlechtes zu den Burgen und deren Bedeutung im 12 (...)

- Reinhard, Johann Jacob: Pragmatische Geschichte des Hauses Geroldsek wie auch derer Reichsherschaften Hohengeroldsek, Lahr und Mahlberg in Schwaben.

- Grimm, the Brothers, Deutsche Sagen, 1816, Nr. 21, p. 28.

- Die Reichs-Matrikel aller Kreise Nebst den Usual-Matrikeln des Kaiserlichen und Reichskammergerichts, Ulm 1796, p. 89.

- Treitschke, Heinrich. History of Germany in the Nineteenth Century, Eng. Trans. 1915. Vol. 1, page 270.

- The Marquis Lucchesini: History of the Causes and Effects of the Rhine Confederation, 1821, p. 394

- Treitschke, Heinrich. The History of Germany in the Nineteenth Century, Eng. Trans., 1915. Vol. 3, page 112.

- http://www.zum.de/Faecher/G/BW/Landeskunde/rhein/territor/geroldseck/museum.htm

- See Reichskreise und Stände des schwäbischen Kreises um 1800 at https://www.leo-bw.de/detail-gis/-/Detail/details/DOKUMENT/kgl_atlas/HABW_06_09/Reichskreise+und+St%C3%A4nde+des+schw%C3%A4bischen+Kreises+um+1800