Henry le Despenser

Henry le Despenser (c.1341–23 August 1406) was an English nobleman and Bishop of Norwich whose reputation as the 'Fighting Bishop' was gained for his part in suppressing the Peasants' Revolt in East Anglia and in defeating the peasants at the Battle of North Walsham in the summer of 1381.

Henry le Despenser | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Norwich | |

14th-century carving of Henry le Despenser, misericord in a chancel stall in King's Lynn Minster | |

| Installed | 12 July 1370 |

| Term ended | 23 August 1406 |

| Predecessor | Thomas Percy |

| Successor | Alexander Tottington |

| Other posts | Archdeacon of Llandaff (around 1364–?) Canon of Salisbury (?–1370) |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 17 December 1362 |

| Consecration | 20 April 1370 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c.1341 |

| Died | 23 August 1406 Elmham, Norfolk |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Parents | Edward le Despenser and Anne Ferrers |

| Alma mater | Oxford University |

As a young man he studied at Oxford University and held numerous positions in the English Church. He fought in Italy before being consecrated as a bishop in 1370. Parliament agreed to allow Despenser to lead a crusade to Flanders in 1383, which was directed against Louis II of Flanders, a supporter of the antipope Clement VII. The crusade was in defence of English economic and political interests. Although well funded, the expedition was poorly equipped and lacked proper military leadership. After initial successes, a disastrous attempt to besiege the city of Ypres forced Despenser to return to England. Upon his return he was impeached in parliament. His temporalities were confiscated by Richard II of England, but were returned in 1385, the year he accompanied the king northward to repel a potential French invasion of Scotland.

Despenser was an energetic and able administrator who staunchly defended his diocese against Lollardy. In 1399, he was among those who stood by Richard, following the landing of Henry Bolingbroke in Yorkshire towards the end of June. He was arrested for refusing to come to terms with Bolingbroke. The following year, he was implicated in the Epiphany Rising, but was pardoned.

Birth and ancestry

Henry le Despenser was the youngest son of Edward le Despenser (1310–1342), by his wife Anne Ferrers (died 1367),[1] daughter of Sir Ralph Ferrers of Groby. Henry was born around 1342, the year that his father was killed at the siege of Vannes.[2] He and his three brothers all grew up to become soldiers. His eldest brother Edward le Despencer, 1st Baron le Despencer[3] (around 1335–1375) was reputed to be one of the greatest knights of his age: he and Henry fought together for Pope Urban V in his war against Milan in 1369.[2] Comparatively little is known of his other siblings: Hugh le Despenser fought abroad and died in Padua in March 1374, Thomas fought in France and died unmarried in 1381 and Gilbert le Despenser died in 1382. Their sister Joan was a nun at Shaftesbury Abbey until her death in 1384.[4]

The le Despenser family originated from the lords of Gomiécourt in north-eastern France.[5] Henry's grandmother Eleanor de Clare was a granddaughter of Edward I of England.

Henry's great-grandfather Hugh le Despenser, 1st Earl of Winchester (1262–1326) and grandfather Hugh Despenser the Younger (1286–1326), who was a favourite of Edward II, were both exiled and later executed after the rebellion of Queen Isabella and her lover Mortimer against Edward II of England.[6] Hugh le Despenser had become Edward II's adviser, holding power until the king's defeat at the Battle of Bannockburn, but he was later restored to favour. His son was appointed the king's chamberlain and enjoyed a still larger share of royal favour. The barons were hostile to the Despensers, due to their acquired wealth and perceived arrogance, and in 1321 they were banished.[7] Their sentences were soon afterwards annulled and from 1322 they played an important role in the governing of the country, but in 1326 Isabella acted against them and both men were tried and executed.

In 1375, Despenser's nephew Thomas le Despenser, 1st Earl of Gloucester succeeded his father Edward. Thomas was captured and killed following the attempt to restore Richard II in the Epiphany Rising.

Early career

In 1353 (as an eleven-year-old boy) Henry 'de Exon' became the canon of Llandaff[8] and a year later he was secured a canonry of Salisbury Cathedral. By the age of nineteen he had become the rector of Bosworth[1] and by February 1361 he was a master at Oxford University, studying civil law.[1] He was ordained on 17 December 1362. By 20 April 1364 he was archdeacon of Llandaff. Of his early life Capgrave tells us that he spent some time in Italy fighting for Pope Urban V in his war against Milan in 1369:

In this same tyme was Ser Herry Spenser a grete werrioure in Ytaile, or the tyme that he was promoted.[2][9]

Bishop of Norwich

In 1370 Despenser, then the canon of Salisbury, was appointed as Bishop of Norwich by a papal bull dated 3 April 1370. He was consecrated at Rome on 20 April and returned to England. He received the spiritualities of his see from the Archbishop of Canterbury on 12 July 1370 and the temporalities from the king on 14 August.[2][10]

Involvement in the suppression of the Peasants' Revolt

During the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, rebels from Kent and Essex marched to London and, once admitted to the city, managed to capture the Tower of London. King Richard, who had promised to agree to all the demands of the peasants, met the rebels outside the city, where the leader of the peasants Wat Tyler was killed and the rebellion was ended. The king's promises were retracted.

The rebellion quickly spread to other parts of England, including the diocese of Norwich, where it lasted for less than a fortnight.[11] On 14 June a group of rebels reached Thetford and from there the insurrection spread over south-western Norfolk towards the Fens. At the same time the rebels, led by a local dyer, Geoffrey Litster, moved across the north-eastern part of the county, urging insurrection throughout the local area. Over the next few days, the rebels converged on Norwich, Lynn and Swaffham.[11] Norwich, then one of the largest and most important cities in the realm, was taken and occupied by Litster and his followers, who caused considerable damage to the property and possessions of their enemies once they managed to enter the city.[11] The Norwich rebels then travelled to Yarmouth, destroying legal records and landowners' possessions; other insurgents moving across north-east Norfolk destroyed court rolls and taxation documents; there were numerous incidents of pillage and extortion across the whole county.[11]

Despenser first heard news of the rising in his own diocese at a time when he was absent at his manor of Burley in Rutland, 100 miles (160 km) west of Norwich. Armed, he hastened back to Norfolk via Peterborough, Cambridge and Newmarket, with a company of only eight lances and a small body of bowmen. His followers increased on the way, and by the time he reached North Walsham, near the Norfolk coast, he had a considerable force under his command. There he found the rebels entrenched and defended by makeshift fortifications. According to Thomas Walsingham,[2] in the Battle of North Walsham the bishop himself led the assault and overpowered his enemies in hand-to-hand fighting. Many were slain or captured, including the rebels' leader, who was hanged, drawn and quartered soon afterwards. Despenser personally superintended Litster's execution. In the following months he proceeded to deal with other rebels in his diocese. But the rigour with which he put down the rebellion made him highly unpopular in Norfolk and in the following year a plot was organised to murder him. The scheme was betrayed in time by one of the conspirators, and the plotters were dealt with by the authorities.[2][12] Following his successful crushing of the rebellion, Despenser commissioned a reredos to sit on the altar in St Luke's chapel, Norwich Cathedral illustrating scenes from Christ's final days. His intention may have been to remind the peasantry to accept their lot in life as Christ had done.[13]

The Norwich Crusade of 1383

Soon after Urban VI had been elected pope in 1378, Robert of Geneva was elected as a rival pope, taking the name Pope Clement VII and removing himself to Avignon. The so-called Western Schism subsequently caused a great crisis in the Church and created rivalry and conflict throughout Christian Europe. It was eventually resolved as a result of the Council of Constance (1414–1418).

In the autumn and winter of 1382, Flanders had been invaded by Charles VI of France. Philip Van Artevelde had fallen at the Battle of Roosebeke and the country had been compelled to submit to the French king, who obliged all the conquered towns to recognise Clement VII. In response to events in Flanders, Pope Urban issued bulls for the proclamation of a crusade, choosing Bishop Despenser to lead a campaign against the followers of Clement VII in Flanders. He granted Despenser extraordinary powers for the fulfillment of his mission and plenary indulgence to those who should take part in or contribute support to it.[14]

Both the commons and King Richard II were enthusiastic about the launch of a crusade to Flanders, for political and economic reasons: revenues from the English wool staple (that had ceased following the advance of the French) could be resumed; sending the bishop and not the king or his uncles to Flanders would enable John of Gaunt's unpopular plans for a royal crusade to Castille to be abandoned; French forces would be drawn away from the Iberian peninsula; and Anglo-Flemish relations would be strengthened. Another advantage in approving a crusade was that its cost would be borne by the Church and not by means of government levies: ever since the Peasants' Revolt, the government was fearful of the consequences of imposing a tax to pay for a new war against the French.

On 6 December 1382, Richard ordered the crusade to be published throughout England.[2] Later that month the bishop and his men took the cross at St. Paul's Cathedral. In February 1383 Parliament, after hesitating in entrusting the mission to a churchman, ultimately assigned to him the subsidy which it had granted the king in the previous October for carrying on the war in Flanders.[15] The king's only stipulation was that the crusaders should await the arrival of William Beauchamp before launching offensive operations against the French and their allies.

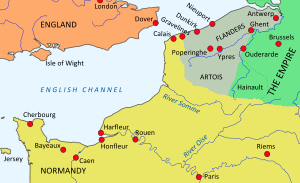

The bishop issued mandates for the publication of the bulls[16] and the archbishop did the same.[17] The enterprise was ardently seconded by the friars and contributions of immense value were made from all quarters, but especially, according to Henry Knighton,[18] from "the rich ladies of England". The English landed at Calais in May 1383 and proceeded to attack Gravelines, which was in the hands of the French. Gravelines, Dunkirk and the neighbouring country (including the towns of Bourbourg, Bergues, Poperinghe, and Nieuport) soon fell. On 25 May the crusaders put to flight a Franco-Flemish army, under the command of the Count of Flanders, in a pitched battle fought near Dunkirk.[19][20] Despenser was then persuaded by his followers to attempt to besiege Ypres, which was to prove to be the turning point of the crusade. He was unwilling to attack the city but his Gantois allies and some of his officers insisted that Ypres should be taken.[21]

.png)

The inhabitants of Ypres were well prepared for a siege by the time the English and their allies arrived and attacked the city on 8 June 1383. Dwellings in the outlying suburbs had been abandoned; the timber from them was used to strengthen the earth ramparts and the stone gates of the city. A mission had been dispatched to Paris to replace artillery powder stocks. The city was well organised under the command of the Castellan of Ypres, John d'Oultre, and had been divided into different defensive sectors. Although the ramparts were low, they were well protected with a double wet ditch, a high thorny hedge reinforced with stakes and a wooden stockade and fire-step.[22]

The English attacked the Temple Gate on the first day but were beaten off. Over the next three days the city gates were attacked simultaneously, without success. Before the end of the first week of the siege, reinforcements arrived to completely encircle the city walls and the outer ditch was breached using soil. On the eighth day (15 June) Despenser attacked the defences with artillery, firing on the Messines Gate and damaging it, but not enough to cause the city defences to be breached. Over the following days of the siege, sustained artillery attacks had little overall effect and the assaults of Despenser's troops were all beaten off.[23] An attempt to drain the ditches seriously threatened the Yprois, but the attempt was unsuccessful and the besieged managed to communicate with the Duke of Burgundy through Louis le Mâle, who was able to raise a large French army to come to the aid of the city.[24] On 8 August, after eight weeks of effort, Despenser abruptly decided to abandon the siege, leaving his allies to continue on their own.

After the débâcle at Ypres, the bishop's forces divided, some going back to England, some remaining with the bishop and others under Sir Thomas Trivet and Sir Hugh Calveley retiring to Bourbourg and Bergues.[25] The bishop and Calveley had wished to advance into France, but Sir William Elmham, Trivet and some of the other commanders refused to go.[26] The bishop, after entering Picardy for some distance, was obliged to fall back upon Gravelines. It turned out that the French had little stomach for a showdown with the English and their allies, preferring instead to negotiate: part of the French army was unwilling to fight when Despenser and Calveley encountered it when moving towards Picardy. It is possible that had King Richard crossed the Channel with a large English army, the campaign would have ended in a famous victory.[27] However, for the demoralised and disease-ridden English forces, the arrival of the French headed by the boy-king Charles VI was decisive. Charles had taken the oriflamme on 2 August and his army was mustered in Arras on 15 August.[28] They advanced into Flanders, reaching Thérouanne by the end of August, Drincham on 5 September, Bergues on 7 September (forcing Trivet's and Elmham's retreat to Bourbourg and Gravelines) and Dunkirk on 9 September. Bourbourg was besieged on 12 September:[29] two days later the Duke of Brittany persuaded the French to negotiate a surrender and the English garrison was given safe conduct from the town.[27] The French army then proceeded along the coast and besieged Gravelines. There, without Despenser's authority, the defenders accepted bribes and the bishop's treasurer pocketed 5000 francs. Despenser at first refused the surrender terms,[29] but a few days later Gravelines was evacuated and Despenser ordered it to be sacked. By the end of October the remaining crusaders had returned across the English Channel.[28]

Career after 1383

Soon after returning from Flanders, the bishop was impeached in parliament, on 26 October 1383, in the presence of the king.[30] The chancellor Michael de la Pole accused him of not mustering his troops at Calais, as had been agreed; not recruiting a high enough number of armed men; refusing to certify properly who his military leaders were; deceiving the king by not allowing a secular lord to command the expedition to Flanders; and disbanding his forces prematurely.[30] Despenser denied all the charges, insisting that enough men had assembled at Ypres, that he had chosen his commanders well and that he had not refused to obey the king's orders. After de la Pole declared the bishop's replies to be insufficient, Despenser requested another hearing to defend himself still further, which was granted. In this hearing Despencer proceeded to blame his own commanders for forcing him to retreat from Ypres and then evacuate the garrisons. All his arguments were refuted and he was blamed for the failure of the expedition. His temporalities were confiscated and he was ordered to repay any costs taken from money gained from the French.[31][32]

Despenser's fall from grace did not last long. Following Scottish incursions into England, it was decided that the 18-year-old King Richard should lead an army into Scotland, marking the start of his military career.[33] In 1385 every magnate of consequence, including Despenser, joined the immense host that advanced north with the king,[34]

finding a country totally waste, where there was nothing to plunder, and little that could even be destroyed, excepting here and there a tower, whose massive walls defied all means of destruction then known, or a cluster of miserable huts.... (Sir Walter Scott, Scotland, vol. 1).[35]

The English army reached Edinburgh, which was sacked, but then retreated back to England, despite John of Gaunt's wish to go on to Fife.[34] The Scottish campaign was one of the last times that Despenser marched with an army.

Henry le Despenser continued to be controversial after his fighting career was over, mainly because of the vigorous methods he used to maintain control over the laity in his diocese and his own cathedral church. He defended the orthodoxy of the church against Lollardy as passionately as he defended his episcopal rights and privileges.

For over a decade Despenser was involved in disputes with the chapter of Norwich Cathedral and with other religious communities in his diocese, mainly concerning the bishop's right to intervene in their internal affairs. In 1394 the monks appealed successfully to Pope Boniface IX against Despenser, but in 1395 matters were still not resolved, for that year the pope ordered William Courtenay the Archbishop of Canterbury to assist in mediating between the parties. On Richard II's instruction, the bishop and the convent instead appeared before Archbishop Courtenay and a royal council, but Courtenay's death in July 1396 prevented a resolution of the dispute from being finalised until 1398, when a royal commission decided in favour of Despenser. Pope Boniface annulled the decisions of the commission in 1401, after the convent appealed to him, but the papal sentences were ignored by Despenser. Eventually the monks came to terms with the bishop and accepted a loss of their autonomy.[36]

Fighting Lollardy

Since 1381, there had been a growing fear of Lollardy among the English political elite. The Lollards had first appeared in the 1370s and had briefly found favour with the upper classes, but in 1382 power was given for the authorities to detain heretics and examine them in a Church court. During the second half of his reign Richard II became steadily more determined to maintain religious orthodoxy and acted increasingly harshly to suppress the Lollards.[37] His successor Henry IV went even further, introducing the death penalty for heresy and for possession of a bible.

Despenser took active steps to maintain orthodoxy in his own diocese. The chronicler Thomas Walsingham praised Henry's actions against the Lollards and contrasted him with his fellow bishops:

He swore, moreover, and did not repent of what he said, that if anyone belonging to that perverse sect should presume to preach in his diocese, they should be taken to the fire or beheaded. Consequently, having understood this, no one belonging to that tendency had any desire to embrace martyrdom, with the result that, up to now, the faith and true religion have remained unaffected within the bounds of his episcopal authority. (Walsingham, Historia Anglicana).[38]

Henry however appears not to have dealt too savagely in dealing with heretics. On 1 May 1399, William Sawtrey, a Norfolk curate and a Lollard, was examined before him. Sawtrey recanted his heresies in public and apparently received no serious punishment, but after moving to London, Sawtrey's heretical preaching attracted the attention of Archbishop Thomas Arundel and he was summoned to appear before a convocation at St. Paul's. Despenser did not attend but sent a written memorandum on 23 February. Following his trial Sawtrey was condemned as a relapsed heretic and was burned in chains at Smithfield in 1401.[1]

Final years

Upon the death of John of Gaunt on 3 February 1399, his son Henry Bolingbroke became the Duke of Lancaster, but Richard II moved quickly to strip him of his patrimony. Bolingbroke resolved to return to England from Paris[39] to claim the restoration of his family estates and in July 1399 he disembarked at Ravenspur.[40] Henry le Despenser reacted to these events by standing loyally by Richard. On 2 July he commissioned three vicars-general to deputise for him whilst he was absent from the diocese and by 10 July he had reached St. Albans with reinforcements for the Duke of York's army.[40] There he joined up with York and they travelled to join the king as he returned from Ireland, whilst Bolingbroke moved south towards Bristol to intercept Richard's supporters.[40] Despenser was with York at Berkeley Castle when he came to terms with Bolingbroke at the end of July, but the bishop refused to submit and was arrested and briefly imprisoned.[41] On 30 September Bolingbroke was proclaimed king in London, an event that Despenser may have witnessed.[42] The bishop attended the first parliament of the new reign on 6 October 1399, in which it was agreed that King Richard should be imprisoned.[42] After this time Despenser's influence in his diocese seems to have diminished, power having shifted to Sir Thomas Erpingham.[43][44]

Henry was implicated in the abortive ‘Epiphany Rising' of January 1400, during which his nephew Thomas, Earl of Gloucester played a key part and was subsequently executed. Thomas had been created Earl of Gloucester by Richard II, but in 1399 was accused of being involved in the death of the son of the Duke of Gloucester and as a result lost his earldom. He joined in the conspiracy of the earls of Rutland, Kent and Huntingdon and was with their army at Cirencester, when they were attacked by the townsmen, who burnt Thomas le Despenser's lodgings. Thomas fled, boarding a ship, but the captain forced him to Bristol, where on 13 January [45] he was released to the mob and beheaded at the high cross.[46]

In the aftermath of the rebellion Henry le Despenser appointed John Derlington, the archdeacon of Norwich, as his vicar-general on 5 February 1400 and then submitted himself to the custody of Archbishop Arundel who accompanied him to Parliament on 20 January 1401.[47] There his enemy Sir Thomas Erpingham falsely accused him of being involved in the plot. He was finally reconciled to Henry IV when the king granted him a pardon in 1401.[48]

Despenser died on 23 August 1406,[49] and was buried in Norwich Cathedral before the high altar. A brass inscription dedicated to him was placed there, but has since been destroyed.[50]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Henry le Despenser | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- DNB

- DNB (1900)

- Burke, B. (1814–1892), A genealogical and heraldic dictionary of the peerage and baronetage of the British Empire (1869) p.670 online version

- Allington-Smith 2003, pp. 3-4.

- Allington-Smith 2003, p. 1.

- McKisack 2004.

- The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 8, Slice 2 On-line version

- "Henry de Exon 1353-?, By exch. with Geoffrey de Cornasano for a canonry with reservn. of preb. in Lanchester colleg. ch., co. Dur., 12 March 1353 (CPL. 11 482; see above p. 32)." (from: 'Canons of Llandaff', Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300–1541: volume 11: The Welsh dioceses (Bangor, Llandaff, St Asaph, St Davids) (1965), pp. 32-34, compid=32454&strquery=llandaff On-line version Date accessed: 13 June 2010.

- Capgrave 1858, p. 158.

- Fasti ecclesiae Anglicanae, p.465

- Reid 1994, p. 86.

- Knighton, Chronicle

- Beckwith, S. (1993). Christ's Body: Identity, Culture and Society in Late Medieval Writings. London: Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-13476-157-9.

- Allington-Smith 2003, chapter 4.

- Walsingham, Hist. Angl. ii. 84

- Walsingham, Hist. Angl. ii. 78 et seq.; Knighton, p. 2673 et seq.

- Wilkins, Concil Magnæ Brit. iii. 176-8

- Knighton. p. 2671

- Westminster Chronicle On-line version Archived 29 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Knighton On-line version Archived 17 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Becke 1927, p. 553.

- Becke 1927, pp. 550-51.

- Becke 1927, pp. 553-54.

- Becke 1927, p. 555.

- Becke 1927, p. 562.

- McKisack 2004, p. 432.

- Allington-Smith 2003, pp. 69-70.

- Saul 1999, p. 105.

- Aston 1965, p. 146.

- Aston 1965, p. 128.

- Aston 1965, p. 131.

- Allington-Smith 2003, pp. 73-78.

- Oxford DNB 'Richard II'

- McKisack 2004, pp. 439-40.

- Scott 1845, p. 224.

- Norwich Cathedral p.297

- Saul 1999, chapter 13.

- Allington-Smith 2003, p. 107.

- History of England p.7

- Allington-Smith 2003, p. 123.

- Chronique de la trahison et mort de Richart II, p.292

- Allington-Smith 2003, p. 124.

- Allington-Smith 2003, p. 99.

- DNB (1900)

- Chronicles of the revolution, 1397–1400: the reign of Richard II By Chris Given-Wilsonp.xv

- DNB 1900

- DNB

- Stubbs 1896, pp. 26-27, 32.

- Le Neve 1854, p. 465.

- Blomefield 1806, chapter 38.

Sources

- British History Online. "Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300–1541: volume 11 – The Welsh dioceses (Bangor, Llandaff, St Asaph, St Davids)".

- Allington-Smith, R. (2003). Henry Despenser: the fighting bishop. Dereham: Larks Press. ISBN 1-904006-16-7.

- Aston, Margaret (November 1965). "The Impeachment of Bishop Despenser". Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. 38 (98): 127. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1965.tb02203.x.

- Becke, Major A.F., Late R.F.A. (January 1927). "Ypres: the story of a thousand years". Journal of the Royal Artillery. 53 (4): 549.

- Norwich Cathedral: City, Church and Diocese, 1096–1996. London: Hambleton Press. 1996. ISBN 1-85285-134-1.

- Blomefield, Francis (1806). "An Essay towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk: Volume 3: The History of the City and County of Norwich, part 1 (The city of Norwich, chapter 38: Of the Bishoprick)". British History Online. pp. 454–599.

- Capgrave, John (1858). The Book of the Illustrious Henries. Translated by Hingeston, Francis Charles. London: Longman etc. OCLC 01005280.

- Davies, R.G. "Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (DNB): Henry Despenser".

- Le Neve, J. (1854). Fasti ecclesiae Anglicanae. https://archive.org/stream/fastiecclesiaean02leneuoft#page/464/mode/2up/search/despenser: Oxford University Press. p. 465.CS1 maint: location (link)

- McKisack, M. (2004) [1959]. The Fourteenth Century 1307–1399. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821712-9.

- Reid, A. (1994). An Historical Atlas of Norfolk. Norwich: Norfolk Museums Service. ISBN 0-903101-60-2.

- Saul, Nigel (1999). Richard II. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07875-7.

- Scott, Sir Walter (1845). Scotland. 1. London: Longman. pp. 222–225. OCLC 977080471.

- Stubbs, William (1896). Constitutional History of England. 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 923437472.

- Tuck, Anthony. "Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (DNB): 'Richard II (1367–1400), king of England and lord of Ireland, and duke of Aquitaine'".

Attribution

Further reading

- Oman, Charles (1906). The Great Revolt of 1381. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 861753209.

- Thompson, Sir Edward (1904). Chronicon Adae de Usk A.D. 1377–1421. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 871729931.

- Williams, Benjamin (1846). Chronicque de la traïson et mort de Richart Deux (in French). London: Aux dépens de la Société. OCLC 03028230.

| Catholic Church titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Thomas Percy |

Bishop of Norwich 1370–1406 |

Succeeded by Alexander Tottington |