Stigand

Stigand[lower-alpha 1] (died 1072) was an Anglo-Saxon churchman in pre-Norman Conquest England who became Archbishop of Canterbury. His birth date is unknown, but by 1020 he was serving as a royal chaplain and advisor. He was named Bishop of Elmham in 1043, and was later Bishop of Winchester and Archbishop of Canterbury. Stigand was an advisor to several members of the Anglo-Saxon and Norman English royal dynasties, serving six successive kings. Excommunicated by several popes for his pluralism in holding the two sees, or bishoprics, of Winchester and Canterbury concurrently, he was finally deposed in 1070, and his estates and personal wealth were confiscated by William the Conqueror. Stigand was imprisoned at Winchester, where he died without regaining his liberty.

Stigand | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Canterbury | |

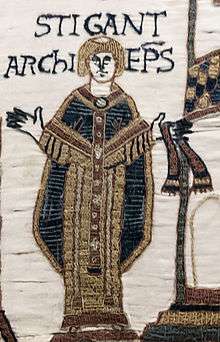

Stigand from the Bayeux Tapestry | |

| Appointed | 1052 |

| Term ended | 11 April 1070 |

| Predecessor | Robert of Jumièges |

| Successor | Lanfranc |

| Other posts | Bishop of Elmham Bishop of Winchester |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 1043 |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Stigand |

| Died | 1072, probably 21 or 22 February |

| Buried | Old Minster, Winchester |

Stigand served King Cnut as a chaplain at a royal foundation at Ashingdon in 1020, and as an advisor then and later. He continued in his role of advisor during the reigns of Cnut's sons, Harold Harefoot and Harthacnut. When Cnut's stepson Edward the Confessor succeeded Harthacnut, Stigand in all probability became England's main administrator. Monastic writers of the time accused Stigand of extorting money and lands from the church, and by 1066 the only estates richer than Stigand's were the royal estates and those of Harold Godwinson.

In 1043 Edward appointed Stigand to the see of Elmham. Four years later he was appointed to the see of Winchester, and then in 1052 to the archdiocese of Canterbury, which Stigand held jointly with Winchester. Five successive popes, including Nicholas II and Alexander II, excommunicated Stigand for holding both Winchester and Canterbury. Stigand was present at the deathbed of King Edward and at the coronation of Harold Godwinson as king of England in 1066. After Harold's death, Stigand submitted to William the Conqueror. On Christmas Day 1066 Ealdred, the Archbishop of York, crowned William King of England. Stigand's excommunication meant that he could only assist at the coronation.

Despite growing pressure for his deposition, Stigand continued to attend the royal court and to consecrate bishops, until in 1070 he was deposed by papal legates and imprisoned at Winchester. His intransigence towards the papacy was used as propaganda by Norman advocates of the view that the English church was backward and needed reform.

Early life

Neither the year nor the date of Stigand's birth is known.[1][lower-alpha 2] He was born in East Anglia, possibly in Norwich,[3] to an apparently prosperous family[4] of mixed English and Scandinavian ancestry,[5] as is shown by the fact that Stigand's name was Norse but his brother's was English.[lower-alpha 3] His brother Æthelmær, also a cleric, later succeeded Stigand as bishop of Elmham.[4] His sister held land in Norwich,[7] but her given name is unrecorded.[8]

Stigand first appears in the historical record in 1020 as a royal chaplain to King Cnut of England (reigned 1016–1035). In that year he was appointed to Cnut's church at Ashingdon, or Assandun,[5][9][10] which was dedicated by the reforming bishop Wulfstan of York.[11][lower-alpha 4] Little is known of Stigand's life during Cnut's reign, but he must have had a place at the royal court,[8] as he witnessed occasional charters.[1] Following Cnut's death Stigand successively served Cnut's sons, Harold Harefoot (reigned 1035–1040) and Harthacnut (reigned 1040–1042).[3][12] After Harthacnut died Stigand became an advisor to Emma of Normandy, Cnut's widow and the mother of Harthacnut and his successor Edward the Confessor.[3][12][lower-alpha 5] He may have been Emma's chaplain,[13] and it is possible that Stigand was already one of her advisors while Cnut was alive, and that he owed his position at Ashingdon to Emma's influence and favour. Because little is known of Stigand's activities before his appointment as a bishop, it is difficult to determine to whom he owed his position.[8]

Bishop of Elmham and Winchester

Stigand was appointed to the see of Elmham shortly after Edward the Confessor's coronation on 3 April 1043,[14] probably on Emma's advice.[15] This was the first episcopal appointment of Edward's reign.[16] The diocese of Elmham covered East Anglia in eastern England,[17] and was one of the poorer episcopal sees at that time.[8][lower-alpha 6] He was consecrated bishop in 1043,[17] but later that year Edward deposed Stigand and deprived him of his wealth.[lower-alpha 7] During the next year, however, Edward returned Stigand to office.[19] The reasons for the deposition are unknown, but it was probably connected to the simultaneous fall from power of the dowager queen, Emma.[20] Some sources state that Emma had invited King Magnus I of Norway, a rival claimant to the English throne, to invade England and had offered her personal wealth to aid Magnus.[21][lower-alpha 8] Some suspected that Stigand had urged Emma to support Magnus, and claimed that his deposition was because of this.[23] Contributing factors in Emma and Stigand's fall included Emma's wealth, and dislike of her political influence, which was linked to the reign of the unpopular Harthacnut.[24]

By 1046 Stigand had begun to witness charters of Edward the Confessor, showing that he was once again in royal favour.[25] In 1047 Stigand was translated to the see of Winchester,[17][26] but he retained Elmham until 1052.[27] He may have owed the preferment to Earl Godwin of Wessex, the father-in-law of King Edward,[28] although that is disputed by some historians.[29] Emma, who had retired to Winchester after regaining Edward's favour, may also have influenced the appointment, either alone or in concert with Godwin. After his appointment to Winchester, Stigand was a witness to all the surviving charters of King Edward during the period 1047 to 1052.[25]

Some historians, such as Frank Barlow and Emma Mason, state that Stigand supported Earl Godwin in his quarrel with Edward the Confessor in 1051–1052;[30][31] others, including Ian Walker, hold that he was neutral.[32] Stigand, whether or not he was a supporter of Godwin's, did not go into exile with the earl.[1][33] The quarrel started over a fight between Eustace of Boulogne, brother-in-law of the king, and men of the town of Dover. The king ordered Godwin to punish the town, and the earl refused. Continued pressure from Edward undermined Godwin's position, and the earl and his family fled England in 1051.[34] The earl returned in 1052 with a substantial armed force but eventually reached a peaceful accord with the king.[30] Some medieval sources state that Stigand took part in the negotiations that reached a peace between the king and his earl;[35] the Canterbury manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle calls Stigand the king's chaplain and advisor during the negotiations.[36]

Archbishop of Canterbury

Appointment to Canterbury and issues with the papacy

The Archbishopric of Canterbury became drawn into the conflict between Edward and Godwin.[37] Pope Leo IX was beginning a reform movement later known as the Gregorian Reform. Leo first focused on improving the clergy and prohibiting simony – the buying and selling of clerical and ecclesiastical offices. In 1049 Leo IX publicly pronounced that he would take more interest in English church matters and would investigate episcopal candidates more strictly before confirming them.[38] When Archbishop Edsige of Canterbury died in 1051 the monks of the cathedral chapter elected Æthelric, a relative of Earl Godwin's, as archbishop.[39] King Edward opposed the election and instead appointed Robert of Jumièges, who was Norman and already Bishop of London. Besides furthering Edward's quarrel with Godwin, the appointment signalled that there were limits to Edward's willingness to compromise on ecclesiastical reform.[38]

Although not known as a reformer before his appointment, Robert returned in 1051 from Rome, where he had gone to be confirmed by the papacy, and opposed the king's choice for Bishop of London on the grounds that the candidate was not suitable. Robert's attempts to recover church property that had been appropriated by Earl Godwin contributed to the quarrel between the earl and the king. When Godwin returned to England in 1052 Robert was outlawed and exiled,[38] following which King Edward appointed Stigand to the archbishopric.[40] The appointment was either a reward from Godwin for Stigand's support during the conflict with Edward or a reward from King Edward for successfully negotiating a peaceful conclusion to the crisis in 1052.[32] Stigand was the first non-monk to be appointed to either English archbishopric since before the days of Dunstan (archbishop from 959 to 988).[40][41][42]

The papacy refused to recognise Stigand's elevation, as Robert was still alive and had not been deprived of office by a pope.[37] Robert of Jumièges appealed to Leo IX, who summoned Stigand to Rome. When Stigand did not appear, he was excommunicated.[43] Historian Nicholas Brooks holds the view that Stigand was not excommunicated at this time, but rather was ordered to refrain from any archiepiscopal functions, such as the consecration of bishops. He argues that in 1062 papal legates sat in council with Stigand, something they would not have done had he been excommunicated.[44] The legates did nothing to alter Stigand's position either,[45] although one of the legates later helped depose Stigand in 1070.[46] However Pope Leo IX and his successors, Victor II and Stephen IX, continued to regard Stigand as uncanonically elected.[43][47]

Stigand did not travel to Rome to receive a pallium,[1] the band worn around the neck that is the symbol of an archbishop's authority,[48] from the pope. Travelling to Rome for the pallium had become a custom, practised by a number of his predecessors.[49] Instead, some medieval chroniclers state that he used Robert of Jumièges' pallium.[1] It is not known if Stigand even petitioned the papacy for a pallium soon after his appointment.[50] Owing to the reform movement, Stigand probably knew the request would be unsuccessful.[37] In 1058 Antipope Benedict X, who opposed much of the reform movement, gave Stigand a pallium.[42][51] However, Benedict was deposed the following year;[42][52] the reforming party declared Benedict an antipope, and nullified all his acts,[42] including Stigand's pallium grant.[53] The exact circumstances that led to Benedict granting a pallium are unknown, whether it was at Stigand's request or was given without prompting.[50]

After his translation to Canterbury, Stigand released Elmham to his brother Æthelmær but retained the bishopric of Winchester.[26] Canterbury and Winchester were the two richest sees in England,[54][55] and while precedent allowed the holding of a rich see along with a poor one, there was no precedent for holding two rich sees concurrently.[56] He may have retained Winchester out of avarice, or his hold on Canterbury may not have been secure.[57] Besides these, he held the abbey of Gloucester and the abbey of Ely and perhaps other abbeys also.[58] Whatever his reasons, the retention of Winchester made Stigand a pluralist: the holder of more than one benefice at the same time.[57] This was a practice that was targeted for elimination by the growing reform movement in the church.[52] Five successive popes (Leo IX, Victor II, Stephen IX, Nicholas II and Alexander II)[51] excommunicated Stigand for holding both Winchester and Canterbury at the same time.[58] It has been suggested by the historian Emma Mason that Edward refused to remove Stigand because this would have undermined the royal prerogative to appoint bishops and archbishops without papal input.[59] Further hurting Stigand's position, Pope Nicholas II in 1061 declared pluralism to be uncanonical unless approved by the pope.[52]

Stigand was later accused of simony by monastic chroniclers, but all such accusations date to after 1066, and are thus suspect owing to the post-Conquest desire to vilify the English Church as corrupt and backward.[60] The medieval chronicler William of Poitiers also claimed that in 1052 Stigand agreed that William of Normandy, the future William the Conqueror, should succeed King Edward. This claim was used as propaganda after the Conquest, but according to the historian David Bates, among others, it is unlikely to be true.[61][62] The position of Stigand as head of the church in England was used to good effect by the Normans in their propaganda before, during and after the Conquest.[63]

Ecclesiastical affairs

The diocese of York took advantage of Stigand's difficulties with the papacy and encroached on the suffragans, or bishops owing obedience to an archbishop, normally subject to Canterbury. York had long been held in common with Worcester, but during the period when Stigand was excommunicated, the see of York also claimed oversight over the sees of Lichfield and Dorchester.[64] In 1062, however, papal legates of Alexander II came to England. They did not depose Stigand, and even consulted with him and treated him as archbishop.[65] He was allowed to attend the council they held and was an active participant with the legates in the business of the council.[66]

Many of the bishops in England did not want to be consecrated by Stigand.[67] Both Giso of Wells and Walter of Hereford travelled to Rome to be consecrated by the pope in 1061, rather than be consecrated by Stigand.[68] During the brief period that he held a legitimate pallium, however, Stigand did consecrate Aethelric of Selsey and Siward of Rochester.[69] Abbots of monasteries, however, came to Stigand for consecration throughout his time as archbishop. These included not only abbots from monastic houses inside his province, such as Æthelsige as abbot of St Augustine's Abbey in Canterbury, but also Baldwin as Abbot of Bury St. Edmunds and Thurstan as Abbot of Ely.[44] After the Norman Conquest, Stigand was accused of selling the office of abbot, but no abbot was deposed for buying the office, so the charge is suspect.[70]

Stigand was probably the most lavish clerical donor of his period, when great men gave to churches on an unprecedented scale.[71] He was a benefactor to the Abbey of Ely,[7] and gave large gold or silver crucifixes to Ely, St Augustine's Abbey in Canterbury, Bury St. Edmunds Abbey, and to his cathedral church at Winchester.[72] The crucifixes given to Ely, Bury and Winchester all appear to have had about life-size figures of Christ with matching figures of the Virgin and John the Evangelist, as is recorded in the monastic histories, and were probably permanently mounted over the altar or elsewhere. These would have been made with thin sheets of precious metal over a wooden core.[73] No comparably early rood crosses with the side figures of Mary and John seem to survive, though we have large painted wooden crucifixes like the German Gero Cross of around 980, and the Volto Santo of Lucca (renewed with a later figure) which is known to have inspired Leofstan, Abbot of Bury (d. 1065) to create a similar figure, perhaps covered in precious metal, on his return from a visit to Rome.[74][lower-alpha 9] To Ely he gave gold and silver vessels for the altar, and a chasuble embroidered in gold "of such inestimable workmanship and worth, that none in the kingdom is considered richer or more valuable".[75] Although it does not appear that Stigand ever travelled to Rome, there are indications that Stigand did go on pilgrimage. A 12th-century life of Saint Willibrord, written at the Abbey of Echternach in what is now Luxembourg, records that "to this place also came Stigand, the eminent archbishop of the English". In the work, Stigand is recorded as giving rich gifts to the abbey as well as relics of saints.[76]

Advisor to the king

During Edward's reign, Stigand was an influential advisor at court and used his position to increase his own wealth as well as that of his friends and family. Contemporary valuations of the lands he controlled at the death of King Edward, as listed in Domesday Book, come to an annual income of about 2500 pounds.[1] There is little evidence, however, that he enriched either Canterbury or Winchester.[1][77] He also appointed his followers to sees within his diocese in 1058, having Siward named Bishop of Rochester and Æthelric installed as Bishop of Selsey.[28] Between his holding of two sees and the appointment of his men to other sees in the southeast of England, Stigand was an important figure in defending the coastline against invasion.[78]

Stigand may have been in charge of the royal administration.[59] He may also have been behind the effort to locate Edward the Atheling and his brother Edmund after 1052, possibly to secure a more acceptable heir to King Edward.[79] His landholdings were spread across ten counties, and in some of those counties, his lands were larger than the king's holdings.[80] Although Norman propagandists claimed that as early as 1051 or 1052 King Edward promised the throne of England to Duke William of Normandy, who later became King William the Conqueror, there is little contemporary evidence of such a promise from non-Norman sources.[81] By 1053, Edward probably realised that he would not have a son from his marriage, and he and his advisors began to search for an heir.[82] Edward the Atheling, the son of King Edmund Ironside (reigned 1016), had been exiled from England in 1017, after his father's death.[79][lower-alpha 10] Although Ealdred, the Bishop of Worcester, went to the Continent in search of Edward the Exile, Ian Walker, the biographer of King Harold Godwinson, feels that Stigand was behind the effort.[79] In the end, although Edward did return to England, he died soon after his return, leaving a young son Edgar the Ætheling.[84]

Final years and legacy

Norman Conquest

King Edward, on his deathbed, left the crown to his brother-in-law Harold Godwinson, the son of Earl Godwin.[84] Stigand performed the funeral services for Edward.[85] Norman writers claimed that Stigand crowned Harold as king in January 1066.[86] This is generally considered false propaganda, as it was in William's interest to portray Harold as uncanonically crowned. If Harold was improperly crowned, then William was merely claiming his rightful inheritance, and not deposing a rightful king.[87] The Bayeux Tapestry depicts Stigand at Harold's coronation, although not actually placing the crown on Harold's head.[88][lower-alpha 11] The English sources claim that Ealdred, the Archbishop of York, crowned Harold, while the Norman sources claim that Stigand did so, with the conflict between the various sources probably tracing to the post-Conquest desire to vilify Harold and depict his coronation as improper.[69] Current historical research has shown that the ceremony was performed by Ealdred, owing to the controversy about Stigand's position.[53][67][69] However, one historian, Pauline Stafford, theorises that both archbishops may have consecrated Harold.[90] Another historian, Frank Barlow, writing in 1979, felt that the fact that some of the English sources do not name who consecrated Harold "tip(s) the balance in favour of Stigand".[91]

Stigand did support Harold, and was present at Edward the Confessor's deathbed.[92] Stigand's controversial position may have influenced Pope Alexander II's support of William the Conqueror's invasion of England.[93][94] The reformers, led by Archdeacon Hildebrand, later Pope Gregory VII, opposed the older type of bishop, rich and installed by the lay powers.[95]

After the death of Harold at the Battle of Hastings, Stigand worked with Earl Edwin and Earl Morcar, as well as Archbishop Ealdred of York, to put Edgar the Ætheling on the throne.[96] This plan did not come to fruition, however, due to opposition from the northern earls and some of the other bishops.[97] Stigand submitted to William the Conqueror at Wallingford in early December 1066,[98][99] and perhaps assisted at his coronation on Christmas Day, 1066,[1] although the coronation was performed by Ealdred.[100] William took Stigand with him to Normandy in 1067,[101] although whether this was because William did not trust the archbishop, as the medieval chronicler William of Poitiers alleges, is uncertain.[102] Stigand was present at the coronation of William's queen, Matilda, in 1068, although once more the ceremony was actually performed by Ealdred.[103]

Deposition and death

After the first rebellions broke out in late 1067 William adopted a policy of conciliation towards the church. He gave Stigand a place at court, as well as giving administrative positions to Ealdred of York and Æthelwig, Abbot of Evesham.[104] Archbishop Stigand appears on a number of royal charters in 1069, along with both Norman and English leaders.[105] He even consecrated Remigius de Fécamp as Bishop of Dorchester in 1067.[1] Once the danger of rebellion was past, however, William had no further need of Stigand.[106] At a council held at Winchester at Easter 1070,[107] the bishops met with papal legates from Alexander II.[108] On 11 April 1070 Stigand was deposed[40] by the papal legate, Ermenfrid, Bishop of Sion in the Alps,[51][109] and was imprisoned at Winchester. His brother Æthelmær, Bishop of Elmham, was also deposed at the same council. Shortly afterwards Aethelric the Bishop of Selsey, Ethelwin the Bishop of Durham and Leofwin Bishop of Lichfield, who was married, were deposed at a council held at Windsor.[4][110][111] There were three reasons given for Stigand's deposition: that he held the bishopric of Winchester in plurality with Canterbury; that he not only occupied Canterbury after Robert of Jumièges fled but also seized Robert's pallium which was left behind; and that he received his own pallium from Benedict X, an anti-pope.[1][112] Some accounts state that Stigand did appear at the council which deposed him, but nothing is recorded of any defence that he attempted. The charges against his brother are nowhere stated, leading to a belief that the depositions were mainly political.[111] That spring he had deposited his personal wealth at Ely Abbey for safekeeping,[7] but King William confiscated it after his deposition, along with his estates.[113] The king appointed Lanfranc, a native of Italy and a scholar and abbot in Normandy, as the new archbishop.[114]

King William appears to have left the initiative for Stigand's deposition to the papacy, and did nothing to hinder Stigand's authority until the papal legates arrived in England to depose the archbishop and reform the English Church. Besides witnessing charters and consecrating Remigius, Stigand appears to have been a member of the royal council, and able to move freely about the country. But after the arrival of the legates, William did nothing to protect Stigand from deposition, and the archbishop later accused the king of acting with bad faith.[105] Stigand may even have been surprised that the legates wished him deposed.[115] It was probably the death of Ealdred in 1069 that moved the pope to send the legates, as that left only one archbishop in England; and he was not considered legitimate and unable to consecrate bishops.[111] The historian George Garnett draws the parallel between the treatment of King Harold in Domesday Book, where he is essentially ignored as king, and Stigand's treatment after his deposition, where his time as archbishop is as much as possible treated as not occurring.[116]

Stigand died in 1072[51] while still imprisoned,[117] and his death was commemorated on 21 February or 22 February.[51] Sometime between his deposition and his death the widow of King Edward and sister of King Harold, Edith of Wessex, visited him in his imprisonment and allegedly told him to take better care of himself.[118] He was buried in the Old Minster at Winchester.[1]

At King Edward's death, only the royal estates and the estates of Harold were larger and wealthier than those held by Stigand.[119] Medieval writers condemned him for his greed and for his pluralism.[1] Hugh the Chanter, a medieval chronicler, claimed that the confiscated wealth of Stigand helped keep King William on the throne.[120] A recent study of his wealth and how it was earned shows that while he did engage in some exploitative methods to gain some of his wealth, other lands were gained through inheritance or through royal favour.[121] The same study shows little evidence that he despoiled his episcopal estates, although the record towards monastic houses is more suspect.[122] There is no complaint in contemporary records about his private life, and the accusations that he committed simony and was illiterate only date from the 12th century.[123]

Although monastic chroniclers after the Norman Conquest accused him of crimes such as perjury and homicide, they do not provide any evidence of those crimes.[124][125] Almost 100 years after his death, another Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, was taunted in 1164 by King Henry II's barons with Stigand's fate for daring to oppose his king.[126] Modern historians views tend to see him as either a wily politician and indifferent bishop or to see him purely in terms of his ecclesiastical failings. The historian Frank Stenton felt that his "whole career shows that he was essentially a politician".[127] Concurring with this, the historian Nick Higham said that "Stigand was a seasoned politician whose career had been built on an accurate reading of the balance of power."[128] Another historian, Eric John, said that "Stigand had a fair claim to be the worst bishop of Christendom".[129] However, the historian Frank Barlow felt that "he was a man of cultured tastes, a patron of the arts who was generous to the monasteries which he held".[55] Alexander Rumble argued that Stigand was unlucky in living past the Conquest, stating that it could be said that Stigand was "unlucky to live so long that he saw in his lifetime not only the end of the Anglo-Saxon state but also the challenging of uncanonical, but hitherto tolerated, practices by a wave of papal reforms".[130]

Notes

- Latin: Stigantus

- The canonical age for ordination as a priest was 30, which would mean that he was born by 990, but dispensations allowing for ordination before the required age were common. If Stigand had been born by 990, he would have been at least 82 at his death, a remarkable age for his time. No chronicler or other source mentions Stigand being of a great age, which argues against him being born before 990.[2]

- Stigand derives from "Stigandr", meaning either "he who goes by long strides" or "the swift footed one".[6]

- The church was dedicated to the memory of the dead of the Battle of Assandun in 1016. It is not known whether Stigand was the first priest appointed to the church.[2]

- Harold Harefoot and Harthacnut were half-brothers, both being sons of Cnut, but by different mothers – Harold's was Ælfgifu, Harthacnut's was Emma of Normandy. Harthacnut and Edward the Confessor were half-brothers, both being sons of Emma of Normandy, by different fathers – Harthacnut's being Cnut and Edward's being Æthelred the Unready, the king whom Cnut had overthrown. Thus, while Harthacnut was related to both his predecessor and successor, Harold Harefoot and Edward were not closely related.[12]

- It was so poor that later, under successive bishops, the seat of the bishopric was moved first to Thetford, and then to Norwich.[18]

- According to later texts, Elmham was briefly passed to Grimketel who was also Bishop of Selsey, at the time, and thus guilty of simony.[1]

- Magnus was the son of St. Olaf of Norway, and his claim to the English throne came from a treaty Harthacnut and Magnus signed around 1038 that provided that if either of the two should die without heirs, the other would inherit their kingdom.[22]

- No early large metal examples have survived, though for example Charlemagne is known to have had one in his chapel at Aachen. For further information on the evolution of the large crucifix, see Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I, pp. 140–149, ISBN 0-85331-270-2.

- Edmund Ironside was the elder half-brother of Edward the Confessor; both were sons of Æthelred, with Edmund being the son of Ælfgifu of York, and Edward being the son of Emma of Normandy. Edmund Ironside had two sons, Edward the Exile and Edmund, who probably died while young in exile. Edward the Exile married while in exile and was the father of Edgar the Ætheling and Margaret of Scotland, the wife of King Malcolm III of Scotland.[83]

- The Tapestry also depicts Stigand wearing a pallium, which Norman sources usually claimed he had no right to wear.[89]

Citations

- Cowdrey "Stigand" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Rumble "From Winchester to Canterbury" Leaders of the Anglo-Saxon Church pp. 173–174

- Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 59

- Douglas William the Conqueror p. 324

- Hill Road to Hastings p. 61

- Rumble "From Winchester to Canterbury" Leaders of the Anglo-Saxon Church p. 175

- Williams English and the Norman Conquest p. 46

- Smith "Archbishop Stigand" Anglo-Norman Studies 16 p. 200

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 28

- Lawson Cnut p. 138

- Barlow English Church 1000–1066 p. 77

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology pp. 28–29

- Stafford Queen Emma and Queen Edith pp. 112–113

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 29

- Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 76

- Higham Death of Anglo-Saxon England p. 122

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 217

- Barlow English Church 1066–1154 pp. 48–49

- Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 77

- Stafford Queen Emma and Queen Edith pp. 248–250

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England p. 426

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England pp. 419–421

- Mason House of Godwine p. 44

- Stafford Unification and Conquest p. 87

- Smith "Archbishop Stigand" Anglo-Norman Studies 16 p. 201

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 223

- Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 87

- Loyn English Church pp. 58–62

- Barlow English Church 1000–1066 p. 108

- Barlow Edward the Confessor p. 123

- Mason House of Godwine p. 65

- Walker Harold p. 49

- Brooks Early History pp. 305–306

- Stafford Unification and Conquest pp. 90–91

- Mason House of Godwine p. 73

- Rex Harold II p. 61

- Smith "Archbishop Stigand" Anglo-Norman Studies 16 pp. 201–203

- Stafford Unification and Conquest pp. 89–92

- Huscroft Ruling England p. 6

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 214

- Knowles Monastic Order p. 66

- Brooks Early History p. 306

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England pp. 465–466

- Brooks Early History p. 307

- Rex Harold II p. 184

- Barlow English Church 1000–1066 p. 306

- Blair Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England p. 108

- Coredon Dictionary p. 209

- Brooks Early History pp. 291, 299, 304

- Darlington "Ecclesiastical Reform" English Historical Review p. 420

- Greenway Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300: Volume 2: Monastic Cathedrals (Northern and Southern Provinces): Canterbury: Archbishops

- Huscroft Ruling England p. 62

- Huscroft Ruling England p. 48

- Higham Death of Anglo-Saxon England p. 137

- Barlow English Church 1000–1066 p. 79

- Brooks Early History p. 205

- Stafford Unification and Conquest p. 94

- Knowles Monastic Order p. 72

- Mason House of Godwine pp. 78–79

- Huscroft Ruling England pp. 46–47

- Bates William the Conqueror pp. 77–78

- Rex Harold II p. 141

- Douglas William the Conqueror p. 170

- Barlow Feudal Kingdom p. 27

- Walker Harold p. 127

- Walker Harold pp. 148–149

- Chibnall Anglo-Norman England p. 39

- Huscroft Ruling England p. 51

- Walker Harold pp. 136–138

- Barlow English Church 1000–1066 pp. 113–115

- Dodwell Anglo-Saxon Art pp. 230–231

- Smith, et al. "Court and Piety" Catholic Historical Review p. 576

- Dodwell Anglo-Saxon Art pp. 211–213, 220 n. 39

- Dodwell Anglo-Saxon Art p. 211

- Dodwell Anglo-Saxon Art pp. 181 and 205

- Smith, et al. "Court and Piety" Catholic Historical Review p. 575

- Brooks Early History pp. 307–309

- Loyn English Church p. 64

- Walker Harold p. 75

- Smith "Archbishop Stigand" Anglo-Norman Studies 16 p. 204

- Stafford Unification and Conquest p. 92

- Barlow Edward the Confessor pp. 214–215

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology pp. 27–29 and p. 57

- Thomas Norman Conquest p. 18

- Rex Harold II p. 197

- Chibnall Anglo-Norman England p. 21

- Higham Death of Anglo-Saxon England pp. 175–180

- Rex Harold II p. 151

- Owen-Crocker "Image Making" Leaders of the Anglo-Saxon Church p. 124

- Stafford Unification and Conquest p. 83

- Barlow English Church 1000–1066 p. 60 footnote 4

- Barlow Edward the Confessor pp. 249–250

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England p. 586

- Loyn English Church p. 98

- Rex Harold II pp. 208–209

- Walker Harold pp. 183–185

- Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 203–206

- Huscroft Ruling England pp. 18–19

- Bates William the Conqueror p. 94

- Bates William the Conqueror p. 96

- Knowles Monastic Order p. 104

- Williams English and the Norman Conquest p. 11

- Bates William the Conqueror pp. 100–101

- Barlow English Church 1066–1154 p. 57

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England pp. 623–624

- Barlow Feudal Kingdom p. 87

- Huscroft Ruling England pp. 60–61

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 590

- Blumenthal Investiture Controversy pp. 148–149

- Barlow Feudal Kingdom p. 93

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England pp. 659–661

- Powell and Wallis House of Lords pp. 33–34

- Brooks Early History p. 309

- Thomas Norman Conquest p. 123

- Loyn English Church p. 69

- Garnett "Coronation and Propaganda" Transactions of the Royal Historical Society pp. 107–108

- Bates William the Conqueror pp. 168–169

- Barlow Godwins p. 161

- Stafford Queen Emma and Queen Edith p. 123 footnote 136

- Rex Harold II p. 79

- Smith "Archbishop Stigand" Anglo-Norman Studies 16 p. 211

- Smith "Archbishop Stigand" Anglo-Norman Studies 16 p. 213

- Barlow English Church 1000–1066 pp. 80–81

- Smith "Archbishop Stigand" Anglo-Norman Studies 16 p. 217

- Stafford Queen Emma and Queen Edith p. 151

- Rumble "From Winchester to Canterbury" Leaders of the Anglo-Saxon Church p. 180

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England p. 466

- Higham Death of Anglo-Saxon England pp. 219–220

- John Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England p. 174

- Rumble "From Winchester to Canterbury" Leaders of the Anglo-Saxon Church p. 179

References

- Barlow, Frank (1970). Edward the Confessor. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01671-8.

- Barlow, Frank (1979). The English Church 1000–1066: A History of the Later Anglo-Saxon Church (Second ed.). New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-49049-9.

- Barlow, Frank (1979). The English Church 1066–1154: A History of the Anglo-Norman Church. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-50236-5.

- Barlow, Frank (1988). The Feudal Kingdom of England 1042–1216 (Fourth ed.). New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-49504-0.

- Barlow, Frank (2003). The Godwins: The Rise and Fall of a Noble Dynasty. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0-582-78440-9.

- Bates, David (2001). William the Conqueror. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1980-3.

- Blair, Peter Hunter (2003). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53777-0.

- Blumenthal, Uta-Renate (1988). The Investiture Controversy: Church and Monarchy from the Ninth to the Twelfth Century. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1386-6.

- Brooks, Nicholas (1984). The Early History of the Church of Canterbury: Christ Church from 597 to 1066. London: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-0041-5.

- Chibnall, Marjorie (1986). Anglo-Norman England 1066–1166. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-15439-6.

- Coredon, Christopher (2007). A Dictionary of Medieval Terms & Phrases (Reprint ed.). Woodbridge, UK: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84384-138-8.

- Cowdrey, H. E. J. (2004). "Stigand (d. 1072)" ((subscription or UK public library membership required)). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26523. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- Darlington, R. R. (July 1936). "Ecclesiastical Reform in the Late Old English Period". The English Historical Review. 51 (203): 385–428. doi:10.1093/ehr/LI.CCIII.385. JSTOR 553127.

- Dodwell, C.R. (1982). Anglo-Saxon Art, A New Perspective. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-0926-X.

- Douglas, David C. (1964). William the Conqueror: The Norman Impact Upon England. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 399137.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Garnett, George (1986). "Coronation and Propaganda: Some Implications of the Norman Claim to the Throne of England in 1066". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. Fifth Series. 36: 91–116. doi:10.2307/3679061. JSTOR 3679061.

- Greenway, Diana E. (1971). Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300: Volume 2: Monastic Cathedrals (Northern and Southern Provinces): Canterbury : Archbishops. Institute for Historical Research. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- Higham, Nick (2000). The Death of Anglo-Saxon England. Stroud, UK: Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-2469-1.

- Hill, Paul (2005). The Road to Hastings: The Politics of Power in Anglo-Saxon England. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3308-3.

- Huscroft, Richard (2005). Ruling England 1042–1217. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0-582-84882-2.

- John, Eric (1996). Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-5053-7.

- Knowles, David (1976). The Monastic Order in England: A History of its Development from the Times of St. Dunstan to the Fourth Lateran Council, 940–1216 (Second reprint ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-05479-6.

- Lawson, M. K. (2000). Cnut: England's Viking King. Stroud, UK: Tempus Publishing, Limited. ISBN 0-7524-2964-7.

- Loyn, H. R. (2000). The English Church, 940–1154. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. ISBN 0-582-30303-6.

- Mason, Emma (2004). House of Godwine: The History of Dynasty. London: Hambledon & London. ISBN 1-85285-389-1.

- Owen-Crocker, Gale R. (2012). "Image Making: Portraits of Anglo-Saxon Church Leaders". In Rumble, Alexander R. (ed.). Leaders of the Anglo-Saxon Church: From Bede to Stigand. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 109–127. ISBN 978-1-84383-700-8.

- Powell, J. Enoch; Wallis, Keith (1968). The House of Lords in the Middle Ages: A History of the English House of Lords to 1540. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Rex, Peter (2005). Harold II: The Doomed Saxon King. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7394-7185-2.

- Rumble, Alexander R. (2012). "From Winchester to Canterbury: Ælheah and Stigand – Bishops, Archbishops and Victims". In Rumble, Alexander R. (ed.). Leaders of the Anglo-Saxon Church: From Bede to Stigand. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 165–182. ISBN 978-1-84383-700-8.

- Smith, Mary Frances (1993). "Archbishop Stigand and the Eye of the Needle". Anglo-Norman Studies Volume 16. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 199–219. ISBN 0-85115-366-6.

- Smith, Mary Frances; Fleming, Robin; Halpin, Patricia (October 2001). "Court and Piety in Late Anglo-Saxon England". The Catholic Historical Review. 87 (4): 569–602. doi:10.1353/cat.2001.0189. JSTOR 25026026.

- Stafford, Pauline (1997). Queen Emma and Queen Edith: Queenship and Women's Power in Eleventh-century England. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-22738-5.

- Stafford, Pauline (1989). Unification and Conquest: A Political and Social History of England in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 0-7131-6532-4.

- Stenton, F. M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Thomas, Hugh (2007). The Norman Conquest: England after William the Conqueror. Critical Issues in History. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-7425-3840-0.

- Walker, Ian (2000). Harold the Last Anglo-Saxon King. Gloucestershire, UK: Wrens Park. ISBN 0-905778-46-4.

- Williams, Ann (2000). The English and the Norman Conquest. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-708-4.

Further reading

- Barlow, Frank (October 1958). "Two Notes: Cnut's Second Pilgrimage and Queen Emma's Disgrace in 1043". The English Historical Review. 73 (289): 649–656. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXIII.289.649. JSTOR 557268.

- John, Eric (April 1979). "Edward the Confessor and the Norman Succession". The English Historical Review. 96 (371): 241–267. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCIV.CCCLXXI.241. JSTOR 566846.

External links

| Catholic Church titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ælfric III |

Bishop of Elmham deposed 1043 |

Succeeded by Grimketel |

| Preceded by Grimketel |

Bishop of Elmham restored 1044–1047 |

Succeeded by Æthelmær |

| Preceded by Ælfwine of Winchester |

Bishop of Winchester 1047–1070 |

Succeeded by Walkelin |

| Preceded by Robert of Jumièges |

Archbishop of Canterbury 1052–1070 |

Succeeded by Lanfranc |