Henley-on-Thames

Henley-on-Thames (/ˌhɛnli-/ (![]()

| Henley-on-Thames | |

|---|---|

Town hall | |

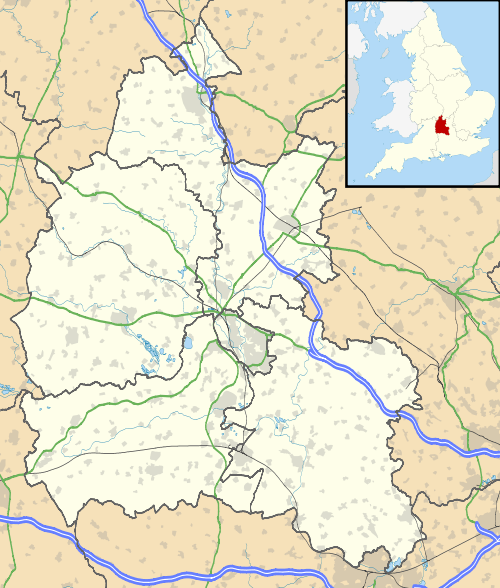

Henley-on-Thames Location within Oxfordshire | |

| Area | 5.58 km2 (2.15 sq mi) |

| Population | 11,619 (2011 Census) |

| • Density | 2,082/km2 (5,390/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | SU7682 |

| • London | 33 miles (53 km) |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Henley-on-Thames |

| Postcode district | RG9 |

| Dialling code | 01491 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Oxfordshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Henley-on-Thames Town Council |

History

The first record of Henley is from 1179, when it is recorded that King Henry II "had bought land for the making of buildings". King John granted the manor of Benson and the town and manor of Henley to Robert Harcourt in 1199. A church at Henley is first mentioned in 1204. In 1205 the town received a paviage grant, and in 1234 the bridge is first mentioned. In 1278 Henley is described as a hamlet of Benson with a chapel. The street plan was probably established by the end of the 13th century.

As a demesne of the crown it was granted in 1337 to John de Molyns, whose family held it for about 250 years. It is said that members for Henley sat in parliaments of Edward I and Edward III, but no writs have been found to substantiate this.

The existing Thursday market, it is believed, was granted by a charter of King John. A market was certainly in existence by 1269; however, the jurors of the assize of 1284 said that they did not know by what warrant the earl of Cornwall held a market and fair in the town of Henley. The existing Corpus Christi fair was granted by a charter of Henry VI.

During the Black Death pandemic that swept through England in the 14th century, Henley lost 60% of its population.[2]

A variation on its name can be seen as "Henley up a Tamys" in 1485.[3]

By the beginning of the 16th century, the town extended along the west bank of the Thames from Friday Street in the south to the Manor, now Phyllis Court, in the north and took in Hart Street and New Street. To the west, it included Bell Street and the Market Place.

Henry VIII granted the use of the titles "mayor" and "burgess", and the town was incorporated in 1568 in the name of the warden, portreeves, burgesses and commonalty. The original charter was issued by Elizabeth I but replaced by one from George I in 1722.[4]

Henley suffered at the hands of both parties in the Civil War. Later, William III rested here on his march to London in 1688, at the nearby recently rebuilt Fawley Court, and received a deputation from the Lords. The town's period of prosperity in the 17th and 18th centuries was due to manufactures of glass and malt, and trade in corn and wool. Henley-on-Thames supplied London with timber and grain.

A workhouse to accommodate 150 people was built at West Hill in Henley in 1790, and was later enlarged to accommodate 250 as the Henley Poor Law Union workhouse.[5]

Prior to 1974 Henley was a municipal borough with a Borough Council comprising twelve Councillors and four Aldermen, headed by a Mayor. The Local Government Act 1972 resulted in the re-organisation of local government in that year. Henley became part of Wallingford District Council, subsequently re-named South Oxfordshire District Council. The borough council became a town council but the role of mayor was retained.

Landmarks and structures

Henley Bridge is a five arched bridge across the river built in 1786. It is a Grade I listed historic structure. During 2011 the bridge underwent a £200,000 repair programme after being hit by the boat Crazy Love in August 2010.[6] About a mile upstream of the bridge is Marsh Lock.

Chantry House is the second Grade I listed building in the town. It is unusual in having more storeys on one side than on the other.[7]

The Church of England parish church of St Mary the Virgin is nearby and has a 16th-century tower.

The Old Bell is a pub in the centre of Henley. The building has been dated from 1325: the oldest-dated building in the town.[8]

To celebrate Queen Victoria's Jubilee, 60 oak trees were planted in the shape of a Victoria Cross near Fairmile, the long straight road to the northwest of the town.[9]

Two notable buildings just outside Henley, in Buckinghamshire, are:

- Fawley Court, a red-brick building designed by Christopher Wren for William Freeman (1684) with subsequent interior remodelling by James Wyatt and landscaping by Lancelot "Capability" Brown.

- Greenlands, which took its present form when owned by W. H. Smith and is now home to Henley Business School

Property

Lloyds Bank's analysis of house price growth in 125 market towns in England over the year to June 2016 (using Land Registry data), found that Henley was the second-most expensive market town in the country with an average property price of £748,001.[10]

Transport

The town's railway station is the terminus of the Henley Branch Line from Twyford. In the past there have been direct services to London Paddington. There are express mainline rail services from Reading (6 miles or 10 km away) to Paddington. Trains from High Wycombe (12 miles or 20 km away) go to London Marylebone. The M4 motorway (junction 8/9) and the M40 motorway (junction 4) are both about 7 miles (12 km) away.

Well-known institutions and organisations

The River and Rowing Museum, located in Mill Meadows, is the town's one museum. It was established in 1998, and officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II. The museum, designed by the architect David Chipperfield, features information on the River Thames, the sport of rowing, and the town of Henley itself.

The University of Reading's Henley Business School is near Henley, as is Henley College.

Rupert House School is a preparatory school located in Bell Street.

Rowing

Henley is a world-renowned centre for rowing. Each summer the Henley Royal Regatta is held on Henley Reach, a naturally straight stretch of the river just north of the town. It was extended artificially. The event became "Royal" in 1851, when Prince Albert became patron of the regatta.[11]

Other regattas and rowing races are held on the same reach, including Henley Women's Regatta, the Henley Boat Races for women's and lightweight teams between Oxford and Cambridge University, Henley Town and Visitors Regatta, Henley Veteran Regatta, Upper Thames Small Boats Head, Henley Fours and Eights Head, and Henley Sculls. These "Heads" often attract strong crews that have won medals at National Championships.[12]

Local rowing clubs include:

- Henley Rowing Club (located upstream of Henley Bridge)

- Leander Club (world-famous, home to Olympic and World Champions, near Henley Bridge)

- Phyllis Court Rowing Club (part of the Phyllis Court Club and set up for recreational rowing)

- Upper Thames Rowing Club (located just upstream from the 3/4-mile mark/Fawley/Old Blades)

- Henley Whalers (associated with UTRC) focus on fixed-seat rowing and sailing.

The regatta depicted throughout Dead in the Water, an episode of the British detective television series Midsomer Murders, was filmed at Henley.

Other sports

Henley has the oldest football team Henley Town F.C. recognised by the Oxfordshire Football Association, they play at The Triangle ground. Henley also has a rugby union club Henley Hawks which play at the Dry Leas ground, a hockey club Henley Hockey Club which play at Jubilee Park, and Henley Cricket Club which has played at Brakspear Ground since 1886.[13] a new club in Henley was started in September 2016 called Henley Lions FC.

Notable people

- Sir Martyn Arbib led the Perpetual fund management company during the late 20th century, unusually based in Henley-on-Thames, rather than London. Arbib was a major benefactor in the establishment of the River and Rowing Museum at Henley, which opened in 1998.

- Mary Blandy (1720–1752) lived at Blandy House her family's home in Henley, now a dental surgery. In 1752, she was hanged for the murder, by poisoning, of her father, Francis Blandy who had opposed her engagement to a Scottish man who was already married. She proclaimed on the day of the hanging in Oxford: "Gentlemen, don't hang me high for the sake of decency". Mary is buried with her parents at St Mary The Virgin's Church, despite that being forbidden at the time for a murderer.[14] She is said to haunt the Kenton Theatre, the family house and St Mary's churchyard.[15]

- Sir William Hamilton (1730–1803), British diplomat, antiquarian, archaeologist and vulcanologist was born in Henley-on-Thames.

- American science fiction writer James Blish (1921–1975) lived in Henley from 1968 until his death.

- Jonathan Bowden (1962–2012) lived in Rotherfield Peppard (post town Henley-on-Thames) throughout the 1970s.

- Russell Brand, English comedian, actor and activist, lives in Henley-on-Thames.[16]

- British engineer Ross Brawn, best known for his role as the technical director of the Scuderia Ferrari f1 team and former team principal of Mercedes Grand Prix.

- Winston Churchill led the Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars, (C Squadron) who were based at "The White House" on Market Place in 1908 and some years after that.

- Sir Frank Crisp (1843–1919), first baronet, lawyer and microscopist, the ideator of Friar Park. The "Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let It Roll)" composed by the former Beatle George Harrison is dedicated to him.

- Esther Deuzeville (1786–1851), as Esther Copley later a writer of children's books and works on domestic economy addressed to the working people, lived here with her parents until her marriage in 1809. There is a plaque to her and her family in the United Reformed Church.[17]

- French general Charles-François Dumouriez (1739–1823) is buried at St Mary the Virgin parish church.

- The Freeman family of Fawley Court: Several generations of Freemans lived at Fawley Court on the outskirts of Henley from 1684 to 1852. They contributed significantly to the development of Henley and the surrounding area as well as more generally to architecture and the study of antiquities (John (Cooke) Freeman and Sambrooke Freeman), and veterinary science and equitation (Strickland Freeman).

- Humphrey Gainsborough (1718–1776), brother of the artist Thomas Gainsborough, was a pastor and inventor who lived in Henley. A blue plaque marks his house, "The Manse".

- Musician and former Beatle George Harrison (1943–2001) purchased and restored the buildings and gardens of Friar Park, Henley-on-Thames in 1970, and lived there until his death. His widow, Olivia Harrison, continues to live on the estate. George and Olivia's only child, Dhani Harrison was raised at Friar Park.

- Michael Heseltine, Baron Heseltine of Thenford preceded Boris Johnson as Conservative MP for Henley-on-Thames.

- Tony Hall, Baron Hall of Birkenhead lives in Henley-on-Thames.

- John Hunt, Baron Hunt of Fawley (1905–1987) had a house in Henley, where he lived from his retirement until his death.

- Politician Boris Johnson was the Member of Parliament until he resigned after being elected Mayor of London in 2008.

- Author Simon Kernick was raised in Henley-on-Thames.

- Politician William Lenthall (1591–1662) was born in Henley-on-Thames. He was Speaker of the House of Commons between 1640 and 1660.

- Hugo Nicolson, music producer.

- Jewellery historian Jack Ogden lives in Henley-on-Thames.

- Author George Orwell (1903–1950) spent some of his formative years in Henley-on-Thames.

- Broadcaster Andrew Peach lives in Henley with his wife and two children.

- Prince Stanisław Albrecht Radziwiłł (1917–1976) is buried at St Anne's church, Fawley Court just outside Henley.

- Singer Lee Ryan lives in Henley.

- Mathematician Marcus du Sautoy lives in Henley.

- Broadcaster Phillip Schofield lives in Henley with his wife and two daughters.

- Financier Urs Schwarzenbach lives at Culham Court, Aston, east of Henley.

- Entrepreneur, philanthropist and workplace revolutionary Dame Stephanie Shirley lives in Henley with her husband.

- Singer Dusty Springfield (1939–1999) has a gravesite and marker in the grounds of St Mary the Virgin parish church. Her ashes were scattered in Henley and in Ireland at the Cliffs of Moher. Each year her fans gather in Henley to celebrate "Dusty Day" on the closest Sunday to her birthday (16 April).

- Sir Ninian Stephen, Australian judge and Governor-General of Australia (1982–1989) was born in Henley

- Harry Stott, joint winner of I'd Do Anything and star of TV show Roman Mysteries.

- Actor David Tomlinson (1917–2000) was born and raised in Henley.

- Author and journalist Andrew Tristem lives in Henley-on-Thames.

- Actor Jonathan Lloyd Walker was born and raised here. He now lives in West Vancouver, Canada.

- Food writer and television presenter Mary Berry lives in Henley.

- Harriet Wheeler, known as the lead singer and songwriter of the 1980s/90s alternative rock band The Sundays.

See also

- Brakspear Brewery, founded in 1779 but now moved to Witney

- Henley Festival, held each July

- Leander Club, one of the world's oldest rowing clubs

- Henley shirt, a garment named after the town because it was the traditional uniform of the rowing clubs

- Stuart Turner Ltd, Henley-based engineering company founded in 1906

Media

Henley's local newspaper is the Henley Standard.

BBC Radio Berkshire (94.6,95.4,104.1,104.4), Heart Berkshire (97.0, 102.9, 103.4), Reading 107 (107.0), all broadcast from Reading, serve an area including Henley, as does Time 106.6 (106.6) broadcast from Slough. London's radio stations such as Capital FM and Magic 105.4 along with a few others can also be received. Regatta Radio (87.7) is broadcast during Henley Royal Regatta.

As Henley is on an overlap of TV regions, it is possible to receive signals from both BBC London and BBC South transmitters, as well as ITV London and ITV Meridian (West). However, the local relay transmitter for Henley only broadcasts programmes from ITV and BBC London, making Henley the only part of Oxfordshire included within the London television region.

References

- "Area: Henley-on-Thames (Parish): Key Figures for 2011 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- Hylton, Stuart (2007). A History of Reading. Phillimore & Co Ltd. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-86077-458-4.

- "Plea Rolls of the Court of Common Pleas; CP 40/892". Anglo-Ammerican Legal Tradition. University of Houston. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Lewis, Samuel, ed. (1931) [1848]. "Hendred, East – Henstead". A Topographical Dictionary of England (Seventh ed.). London: Samuel Lewis. pp. 478–482. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- "Henley, Oxfordshire". The Workhouse. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- "Bridge damage costs £200,000 in repairs". Henley Standard. 5 September 2011. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014.

- Historic England. "Chantry House (Grade I) (1047033)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- "Old Bell". UK: Brakspear. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Map". Google Maps. Google.

- "The 10 most expensive market towns revealed - Money Observer". www.moneyobserver.com.

- ""Royal Patronage", Henley Royal Regatta". Archived from the original on 19 August 2013.

- "2011 Henley Royal Regatta". world rowing. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- "About Us - Henley Cricket Club". www.henleycricketclub.co.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- McKenzie, Andrea. "Blandy, Mary". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2620. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Ian (12 January 2012). "Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin, Henley on Thames". Mysterious Britain and Ireland. Retrieved 5 April 2020. (updated 26 December 2018)

- "Russell Brand taking to the water for big day". Henley Standard. 14 August 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- Mitchell, Rosemary, "Copley, Esther (1786–1851)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (Oxford: OUP, 2004). . Subscription required, accessed 8 May 2010

Further reading

- Allison, Barbara (2011). "Henley's Major Inns in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries". Oxoniensia. Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society. LXXVI: 55–79. ISSN 0308-5562.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Cardinals (2014). Friar Park: A Pictorial History. Campfire Publishing. ISBN 978-1502573261.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 335–345. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Townley, Simon C, ed. (2011). A History of the County of Oxford. Victoria County History. 16: Binfield Hundred (Part One): Henley-on-Thames and Environs. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer. ISBN 978-1-904356-38-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Henley Guide. With fifteen illustrations". London: Hickman and Stapledon. 1826{{inconsistent citations}} Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Henley-on-Thames. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henley-on-Thames. |