Dio Chrysostom

Dio Chrysostom (/ˈdiːoʊ ˈkrɪsəstəm, krɪˈsɒstəm/; Greek: Δίων Χρυσόστομος Dion Chrysostomos), Dion of Prusa or Dio Cocceianus (c. 40 – c. 115 AD), was a Greek orator, writer, philosopher and historian of the Roman Empire in the 1st century AD. Eighty of his Discourses (or Orations; Λόγοι) are extant, as well as a few Letters and a funny mock essay "In Praise of Hair", as well as a few other fragments. His surname Chrysostom comes from the Greek chrysostomos (χρυσόστομος), which literally means "golden-mouthed".

Life

He was born at Prusa (now Bursa) in the Roman province of Bithynia (now part of northwestern Turkey). His father, Pasicrates, seems to have bestowed great care on his son Dio's education and the early training of his mind. At first he occupied himself in his native place, where he held important offices, with the composition of speeches and other rhetorical and sophistical essays, but he later devoted himself with great zeal to the study of philosophy. He did not, however, confine himself to any particular sect or school, nor did he give himself up to any profound speculations, his object being rather to apply the doctrines of philosophy to the purposes of practical life, and more especially to the administration of public affairs, and thus to bring about a better state of things. The Stoic and Platonist philosophies, however, appear to have had the greatest charms for him.

He went to Rome during Vespasian's reign (69–79 AD), by which time he seems to have got married and had a child.[1] He became a critic of the Emperor Domitian,[2] who banished him from Rome, Italy, and Bithynia in 82 for advising one of the Emperor's conspiring relatives.[3] On the advice of the Delphic oracle,[4] he put on the clothes of a beggar,[5] and with nothing in his pocket but a copy of Plato's Phaedo and Demosthenes's oration on the Embassy, he lived the life of a Cynic philosopher, undertaking a journey to the countries in the north and east of the Roman empire. He thus visited Thrace, Mysia, Scythia, and the country of the Getae,[6] and owing to the power and wisdom of his orations, he met everywhere with a kindly reception, and did much good.[7] He was a friend of Nerva,[8] and when Domitian was murdered in 96 AD, Dio used his influence with the army stationed on the frontier in favour of Nerva. Under Emperor Nerva's reign, his exile was ended, and he was able to return home to Prusa. He adopted the surname Cocceianus in later life to honour the support given to him by the emperor,[9] whose full name was Marcus Cocceius Nerva. Nerva's successor, Trajan, entertained the highest esteem for Dio,[10] and showed him the most marked favour. His kindly disposition gained him many eminent friends, such as Apollonius of Tyana and Euphrates of Tyre, and his oratory the admiration of all. In his later life Dio had considerable status in Prusa, and there are records of him being involved in an urban renewal lawsuit about 111.[9] He probably died a few years later.

Writings

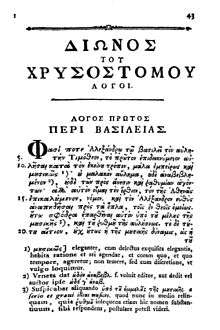

Dio Chrysostom was part of the Second Sophistic school of Greek philosophers which reached its peak in the early 2nd century. He was considered as one of the most eminent of the Greek rhetoricians and sophists by the ancients who wrote about him, such as Philostratus,[11] Synesius,[12] and Photius.[13] This is confirmed by the eighty orations of his which are still extant, and which were the only ones known in the time of Photius. These orations appear to be written versions of his oral teaching, and are like essays on political, moral, and philosophical subjects. They include four orations on Kingship addressed to Trajan on the virtues of a sovereign; four on the character of Diogenes of Sinope, on the troubles to which men expose themselves by deserting the path of Nature, and on the difficulties which a sovereign has to encounter; essays on slavery and freedom; on the means of attaining eminence as an orator; political discourses addressed to various towns which he sometimes praises and sometimes blames, but always with moderation and wisdom; on subjects of ethics and practical philosophy, which he treats in a popular and attractive manner; and lastly, orations on mythical subjects and show-speeches. He argued strongly against permitting prostitution.[14] He also claimed that the epics of Homer had been translated and were sung in India;[15] this is unlikely to be true, and there may have been confusion with the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, of which there are some parallels in subject matter.[16] Two orations of his (37 and 64) are now assigned to Favorinus. Besides the eighty orations we have fragments of fifteen others, and there are extant also five letters under Dio's name.

Dio believed that it was the Trojans that had won the Trojan War.[17] Some modern researchers also agree with this. For example, A. Belyakov and O. Matveychev in their book also adhere to this point of view referring to a number of modern sources.[18]

He wrote many other philosophical and historical works, none of which survive. One of these works, Getica, was on the Getae,[11] which the Suda incorrectly attributes to Dio Cassius.[19]

Editions

- Hans von Arnim, Dionis Prusaensis quem uocant Chrysostomum quae exstant omnia (Berlin, 1893–1896).

- C. Bost-Pouderon, Dion Chrysostome. Trois discours aux villes (Orr. 33-35) (Salerne, 2006).

- C. Bost-Pouderon (ed.), Dion de Pruse dit Dion Chrysostome. Oeuvres (Or. XXXIII-XXXVI (Paris, CUF, 2011).

- Trans. J. W. Cohoon, Dio Chrysostom, I, Discourses 1-11, 1932. Harvard University Press, Loeb Classical Library:

- Trans. J. W. Cohoon, Dio Chrysostom, II, Discourses 12-30, 1939.

- Trans. J. W. Cohoon & H. Lamar Crosby, Dio Chrysostom, III, Discourses 31-36, 1940.

- Trans. H. Lamar Crosby, Dio Chrysostom, IV, Discourses 37-60, 1946.

- Trans. H. Lamar Crosby, Dio Chrysostom, V, Discourses 61-80. Fragments. Letters, 1951.

- H.-G. Nesselrath (ed), Dio von Prusa. Der Philosoph und sein Bild [Discourses 54-55, 70-72], introduction, critical edition, commentary, translation, and essays by E. Amato et al., Tübingen 2009.

Notes

- Dio Chrysostom, Orat. xlvi. 13

- Dio Chrysostom, Orat. iii. 13

- Dio Chrysostom, Orat. xiii. 1

- Dio Chrysostom, Orat. xiii. 9

- Dio Chrysostom, Orat. xiii. 11

- Dio Chrysostom, Orat. xii. 16

- Dio Chrysostom, Orat. xxxvi.; comp. Orat. xiii. 11 ff.

- Dio Chrysostom, Orat. xlv. 2

- Pliny, Epistles, x. 81

- Dio Chrysostom, Orat. iii. 2

- Philostratus, Vitae sophistorum i.7

- Synesius, Dion

- Photius, Bibl. Cod. 209

- Dio Chrysostom, Orat. vii.133‑152

- Dio Chrysostom, Orat. liii. 6-8

- McEvilley, T., (2002), The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies, page 387. Allworth Communications.

- "Dio Chrysostom - Luwian Studies".

- "Trojan Horse of Western History".

- Suda, Dion

Further reading

- Eugenio Amato, Xenophontis imitator fidelissimus. Studi su tradizione e fortuna erudite di Dione Crisostomo tra XVI e XIX secolo (Alessandria: Edizioni dell'Orso, 2011) (Hellenica, 40).

- Eugenio Amato, Traiani Praeceptor. Studi su biografia, cronologia e fortuna di Dione Crisostomo (Besansçon: PUFC, 2014).

- T. Bekker-Nielsen, Urban Life and Local Politics in Roman Bithynia: The Small World of Dion Chrysostomos (Aarhus, 2008).

- P. Desideri, Dione di Prusa (Messina-Firenze, 1978).

- A. Gangloff, Dion Chrysostome et les mythes. Hellénisme, communication et philosophie politique (Grenoble, 2006).

- B.F. Harris, "Dio of Prusa", in Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt 2.33.5 (Berlin, 1991), 3853-3881.

- C.P. Jones, The Roman World of Dio Chrysostom (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1978).

- Simon Swain, Hellenism and Empire. Language, Classicism, and Power in the Greek World, AD 50-250 (Oxford, 1996), 187–241.

- Simon Swain. Dio Chrysostom (Oxford, 2000).

- Aldo Brancacci, Rhetorike philosophousa. Dione Crisostomo nella cultura antica e bizantina (Napoli: Bibliopolis, 1986) (Elenchos, 11).

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dio Chrysostom |

Texts of Dio

- Complete works at LacusCurtius (English translation complete; some items in Greek also)

Secondary material

- Dio Chrysostom at Livius.Org

- Introduction to the Loeb translation at LacusCurtius