Happiness

The term happiness is used in the context of mental or emotional states, including positive or pleasant emotions ranging from contentment to intense joy.[1] It is also used in the context of life satisfaction, subjective well-being, eudaimonia, flourishing and well-being.[2][3]

Since the 1960s, happiness research has been conducted in a wide variety of scientific disciplines, including gerontology, social psychology and positive psychology, clinical and medical research and happiness economics.

Definitions

'Happiness' is the subject of debate on usage and meaning,[4][5][6][7] and on possible differences in understanding by culture.[8][9]

The word is mostly used in relation to two factors:[10]

- the current experience of the feeling of an emotion (affect) such as pleasure or joy,[1] or of a more general sense of 'emotional condition as a whole'.[11] For instance Daniel Kahneman has defined happiness as "what I experience here and now".[12] This usage is prevalent in dictionary definitions of happiness.[13][14][15]

- appraisal of life satisfaction, such as of quality of life.[16] For instance Ruut Veenhoven has defined happiness as "overall appreciation of one's life as-a-whole."[17][18] Kahneman has said that this is more important to people than current experience.[19]

Some usages can include both of these factors. Subjective well-being (swb)[20] includes measures of current experience (emotions, moods, and feelings) and of life satisfaction.[21] For instance Sonja Lyubomirsky has described happiness as “the experience of joy, contentment, or positive well-being, combined with a sense that one's life is good, meaningful, and worthwhile.”[22] Eudaimonia,[23] is a Greek term variously translated as happiness, welfare, flourishing, and blessedness. Xavier Landes[24] has proposed that happiness include measures of subjective wellbeing, mood and eudaimonia.[25]

These differing uses can give different results.[26] For instance the correlation of income levels has been shown to be substantial with life satisfaction measures, but to be far weaker, at least above a certain threshold, with current experience measures.[27][28] Whereas Nordic countries often score highest on swb surveys, South American countries score higher on affect-based surveys of current positive life experiencing.[29]

The implied meaning of the word may vary depending on context,[30] qualifying happiness as a polyseme and a fuzzy concept.

Some users accept these issues, but continue to use the word because of its convening power.[31]

Philosophy

Philosophy of happiness is often discussed in conjunction with ethics. Traditional European societies, inherited from the Greeks and from Christianity, often linked happiness with morality, which was concerned with the performance in a certain kind of role in a certain kind of social life. However, with the rise of individualism, begotten partly by Protestantism and capitalism, the links between duty in a society and happiness were gradually broken. The consequence was a redefinition of the moral terms. Happiness is no longer defined in relation to social life, but in terms of individual psychology. Happiness, however, remains a difficult term for moral philosophy. Throughout the history of moral philosophy, there has been an oscillation between attempts to define morality in terms of consequences leading to happiness and attempts to define morality in terms that have nothing to do with happiness at all.[32]

In the Nicomachean Ethics, written in 350 BCE, Aristotle stated that happiness (also being well and doing well) is the only thing that humans desire for their own sake, unlike riches, honour, health or friendship. He observed that men sought riches, or honour, or health not only for their own sake but also in order to be happy. For Aristotle the term eudaimonia, which is translated as 'happiness' or 'flourishing' is an activity rather than an emotion or a state. Eudaimonia (Greek: εὐδαιμονία) is a classical Greek word consists of the word "eu" ("good" or "well being") and "daimōn" ("spirit" or "minor deity", used by extension to mean one's lot or fortune). Thus understood, the happy life is the good life, that is, a life in which a person fulfills human nature in an excellent way. Specifically, Aristotle argued that the good life is the life of excellent rational activity. He arrived at this claim with the "Function Argument". Basically, if it is right, every living thing has a function, that which it uniquely does. For Aristotle human function is to reason, since it is that alone which humans uniquely do. And performing one's function well, or excellently, is good. According to Aristotle, the life of excellent rational activity is the happy life. Aristotle argued a second best life for those incapable of excellent rational activity was the life of moral virtue.

Western ethicists have made arguments for how humans should behave, either individually or collectively, based on the resulting happiness of such behavior. Utilitarians, such as John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham, advocated the greatest happiness principle as a guide for ethical behavior.[33]

Friedrich Nietzsche critiqued the English Utilitarians' focus on attaining the greatest happiness, stating that "Man does not strive for happiness, only the Englishman does." Nietzsche meant that making happiness one's ultimate goal and the aim of one's existence, in his words "makes one contemptible." Nietzsche instead yearned for a culture that would set higher, more difficult goals than "mere happiness." He introduced the quasi-dystopic figure of the "last man" as a kind of thought experiment against the utilitarians and happiness-seekers. these small, "last men" who seek after only their own pleasure and health, avoiding all danger, exertion, difficulty, challenge, struggle are meant to seem contemptible to Nietzsche's reader. Nietzsche instead wants us to consider the value of what is difficult, what can only be earned through struggle, difficulty, pain and thus to come to see the affirmative value suffering and unhappiness truly play in creating everything of great worth in life, including all the highest achievements of human culture, not least of all philosophy.[34][35]

In 2004 Darrin McMahon claimed, that over time the emphasis shifted from the happiness of virtue to the virtue of happiness.[36]

Not all cultures seek to maximise happiness,[37][38][39] and some cultures are averse to happiness.[40][41]

Religion

Eastern religions

Buddhism

Happiness forms a central theme of Buddhist teachings.[42] For ultimate freedom from suffering, the Noble Eightfold Path leads its practitioner to Nirvana, a state of everlasting peace. Ultimate happiness is only achieved by overcoming craving in all forms. More mundane forms of happiness, such as acquiring wealth and maintaining good friendships, are also recognized as worthy goals for lay people (see sukha). Buddhism also encourages the generation of loving kindness and compassion, the desire for the happiness and welfare of all beings.[43][44]

Hinduism

In Advaita Vedanta, the ultimate goal of life is happiness, in the sense that duality between Atman and Brahman is transcended and one realizes oneself to be the Self in all.

Patanjali, author of the Yoga Sutras, wrote quite exhaustively on the psychological and ontological roots of bliss.[45]

Confucianism

The Chinese Confucian thinker Mencius, who had sought to give advice to ruthless political leaders during China's Warring States period, was convinced that the mind played a mediating role between the "lesser self" (the physiological self) and the "greater self" (the moral self), and that getting the priorities right between these two would lead to sage-hood. He argued that if one did not feel satisfaction or pleasure in nourishing one's "vital force" with "righteous deeds", then that force would shrivel up (Mencius, 6A:15 2A:2). More specifically, he mentions the experience of intoxicating joy if one celebrates the practice of the great virtues, especially through music.[46]

Abrahamic religions

Judaism

Happiness or simcha (Hebrew: שמחה) in Judaism is considered an important element in the service of God.[47] The biblical verse "worship The Lord with gladness; come before him with joyful songs," (Psalm 100:2) stresses joy in the service of God. A popular teaching by Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, a 19th-century Chassidic Rabbi, is "Mitzvah Gedolah Le'hiyot Besimcha Tamid," it is a great mitzvah (commandment) to always be in a state of happiness. When a person is happy they are much more capable of serving God and going about their daily activities than when depressed or upset.[48]

Roman Catholicism

The primary meaning of "happiness" in various European languages involves good fortune, chance or happening. The meaning in Greek philosophy, however, refers primarily to ethics.

In Catholicism, the ultimate end of human existence consists in felicity, Latin equivalent to the Greek eudaimonia, or "blessed happiness", described by the 13th-century philosopher-theologian Thomas Aquinas as a Beatific Vision of God's essence in the next life.[49]

According to St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, man's last end is happiness: "all men agree in desiring the last end, which is happiness."[50] However, where utilitarians focused on reasoning about consequences as the primary tool for reaching happiness, Aquinas agreed with Aristotle that happiness cannot be reached solely through reasoning about consequences of acts, but also requires a pursuit of good causes for acts, such as habits according to virtue.[51] In turn, which habits and acts that normally lead to happiness is according to Aquinas caused by laws: natural law and divine law. These laws, in turn, were according to Aquinas caused by a first cause, or God.

According to Aquinas, happiness consists in an "operation of the speculative intellect": "Consequently happiness consists principally in such an operation, viz. in the contemplation of Divine things." And, "the last end cannot consist in the active life, which pertains to the practical intellect." So: "Therefore the last and perfect happiness, which we await in the life to come, consists entirely in contemplation. But imperfect happiness, such as can be had here, consists first and principally in contemplation, but secondarily, in an operation of the practical intellect directing human actions and passions."[52]

Human complexities, like reason and cognition, can produce well-being or happiness, but such form is limited and transitory. In temporal life, the contemplation of God, the infinitely Beautiful, is the supreme delight of the will. Beatitudo, or perfect happiness, as complete well-being, is to be attained not in this life, but the next.[53]

Islam

Al-Ghazali (1058–1111), the Muslim Sufi thinker, wrote "The Alchemy of Happiness", a manual of spiritual instruction throughout the Muslim world and widely practiced today.

Psychology

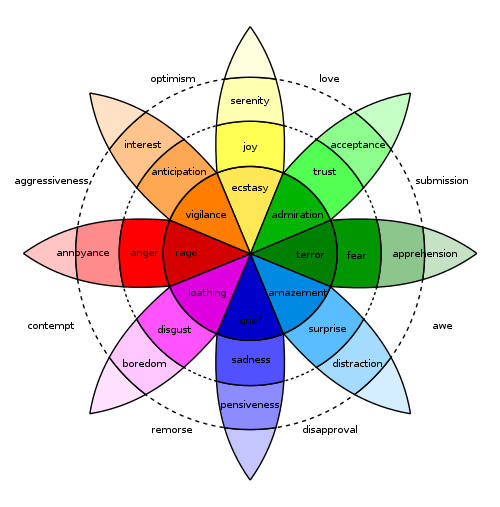

Happiness in its broad sense is the label for a family of pleasant emotional states, such as joy, amusement, satisfaction, gratification, euphoria, and triumph.[54]

Happiness can be examined in experiential and evaluative contexts. Experiential well-being, or "objective happiness", is happiness measured in the moment via questions such as "How good or bad is your experience now?". In contrast, evaluative well-being asks questions such as "How good was your vacation?" and measures one's subjective thoughts and feelings about happiness in the past. Experiential well-being is less prone to errors in reconstructive memory, but the majority of literature on happiness refers to evaluative well-being. The two measures of happiness can be related by heuristics such as the peak-end rule.[55]

Some commentators focus on the difference between the hedonistic tradition of seeking pleasant and avoiding unpleasant experiences, and the eudaimonic tradition of living life in a full and deeply satisfying way.[56]

Theories on how to achieve happiness include "encountering unexpected positive events",[57] "seeing a significant other",[58] and "basking in the acceptance and praise of others".[59] However others believe that happiness is not solely derived from external, momentary pleasures.[60]

Theories

Maslow's hierarchy of needs

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is a pyramid depicting the levels of human needs, psychological, and physical. When a human being ascends the steps of the pyramid, he reaches self-actualization. Beyond the routine of needs fulfillment, Maslow envisioned moments of extraordinary experience, known as peak experiences, profound moments of love, understanding, happiness, or rapture, during which a person feels more whole, alive, self-sufficient, and yet a part of the world. This is similar to the flow concept of Mihály Csíkszentmihályi.

Self-determination theory

Self-determination theory relates intrinsic motivation to three needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness.

Modernization and freedom of choice

Ronald Inglehart has traced cross-national differences in the level of happiness based on data from the World Values Survey.[61] He finds that the extent to which a society allows free choice has a major impact on happiness. When basic needs are satisfied, the degree of happiness depends on economic and cultural factors that enable free choice in how people live their lives. Happiness also depends on religion in countries where free choice is constrained.[62]

Positive psychology

Since 2000 the field of positive psychology has expanded drastically in terms of scientific publications, and has produced many different views on causes of happiness, and on factors that correlate with happiness.[63] Numerous short-term self-help interventions have been developed and demonstrated to improve happiness.[64][65]

Measurement

People have been trying to measure happiness for centuries. In 1780, the English utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham proposed that as happiness was the primary goal of humans it should be measured as a way of determining how well the government was performing.[66]

Several scales have been developed to measure happiness:

- The Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS) is a four-item scale, measuring global subjective happiness from 1999. The scale requires participants to use absolute ratings to characterize themselves as happy or unhappy individuals, as well as it asks to what extent they identify themselves with descriptions of happy and unhappy individuals.[67][68]

- The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) from 1988 is a 20-item questionnaire, using a five-point Likert scale (1 = very slightly or not at all, 5 = extremely) to assess the relation between personality traits and positive or negative affects at "this moment, today, the past few days, the past week, the past few weeks, the past year, and in general".[69][70] A longer version with additional affect scales was published 1994.[71]

- The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) is a global cognitive assessment of life satisfaction developed by Ed Diener. A seven-point Likert scale is used to agree or disagree with five statements about one's life.[72][73]

- The Cantril ladder method[74] has been used in the World Happiness Report. Respondents are asked to think of a ladder, with the best possible life for them being a 10, and the worst possible life being a 0. They are then asked to rate their own current lives on that 0 to 10 scale.[75][74]

- Positive Experience; the survey by Gallup asks if, the day before, people experienced enjoyment, laughing or smiling a lot, feeling well-rested, being treated with respect, learning or doing something interesting. 9 of the top 10 countries in 2018 were South American, led by Paraguay and Panama. Country scores range from 85 to 43.[76]

Since 2012, a World Happiness Report has been published. Happiness is evaluated, as in “How happy are you with your life as a whole?”, and in emotional reports, as in “How happy are you now?,” and people seem able to use happiness as appropriate in these verbal contexts. Using these measures, the report identifies the countries with the highest levels of happiness. In subjective well-being measures, the primary distinction is between cognitive life evaluations and emotional reports.[77]

The UK began to measure national well being in 2012,[78] following Bhutan, which had already been measuring gross national happiness.[79][80]

Happiness has been found to be quite stable over time.[81][82]

Relationship to physical characteristics

As of 2016, no evidence of happiness causing improved physical health has been found; the topic is being researched at the Lee Kum Sheung Center for Health and Happiness at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.[83] A positive relationship has been suggested between the volume of the brain's gray matter in the right precuneus area and one's subjective happiness score.[84]

Possible limits on happiness seeking

Some studies, including 2018 work by June Gruber a psychologist at University of Colorado, has suggested that seeking happiness can have negative effects, such as failure to meet over-high expectations.[85][86] A 2012 study found that psychological well-being was higher for people who experienced both positive and negative emotions.[87][88] Other research has analysed possible trade-offs between happiness and meaning in life.[89][90][91]

Not all cultures seek to maximise happiness.[40][92][93][38][39]

Sigmund Freud said that all humans strive after happiness, but that the possibilities of achieving it are restricted because we "are so made that we can derive intense enjoyment only from a contrast and very little from the state of things."[94]

Economic and political views

In politics, happiness as a guiding ideal is expressed in the United States Declaration of Independence of 1776, written by Thomas Jefferson, as the universal right to "the pursuit of happiness."[95] This seems to suggest a subjective interpretation but one that goes beyond emotions alone. It has to be kept in mind that the word happiness meant "prosperity, thriving, wellbeing" in the 18th century and not the same thing as it does today. In fact, happiness .[96]

Common market health measures such as GDP and GNP have been used as a measure of successful policy. On average richer nations tend to be happier than poorer nations, but this effect seems to diminish with wealth.[97][98] This has been explained by the fact that the dependency is not linear but logarithmic, i.e., the same percentual increase in the GNP produces the same increase in happiness for wealthy countries as for poor countries.[99][100][101][102] Increasingly, academic economists and international economic organisations are arguing for and developing multi-dimensional dashboards which combine subjective and objective indicators to provide a more direct and explicit assessment of human wellbeing. Work by Paul Anand and colleagues helps to highlight the fact that there many different contributors to adult wellbeing, that happiness judgement reflect, in part, the presence of salient constraints, and that fairness, autonomy, community and engagement are key aspects of happiness and wellbeing throughout the life course.

Libertarian think tank Cato Institute claims that economic freedom correlates strongly with happiness[103] preferably within the context of a western mixed economy, with free press and a democracy. According to certain standards, East European countries when ruled by Communist parties were less happy than Western ones, even less happy than other equally poor countries.[104]

Since 2003, empirical research in the field of happiness economics, such as that by Benjamin Radcliff, professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame, supported the contention that in democratic countries life satisfaction is strongly and positively related to the social democratic model of a generous social safety net, pro-worker labor market regulations, and strong labor unions.[105] Similarly, there is evidence that public policies which reduce poverty and support a strong middle class, such as a higher minimum wage, strongly affect average levels of well-being.[106]

It has been argued that happiness measures could be used not as a replacement for more traditional measures, but as a supplement.[107] According to the Cato institute, people constantly make choices that decrease their happiness, because they have also more important aims. Therefore, government should not decrease the alternatives available for the citizen by patronizing them but let the citizen keep a maximal freedom of choice.[108]

Good mental health and good relationships contribute more than income to happiness and governments should take these into account.[109]

Contributing factors and research outcomes

Research on positive psychology, well-being, eudaimonia and happiness, and the theories of Diener, Ryff, Keyes, and Seligmann covers a broad range of levels and topics, including "the biological, personal, relational, institutional, cultural, and global dimensions of life."[110]

See also

- Action for Happiness

- Aversion to happiness

- Biopsychosocial model

- Bluebird of happiness

- Extraversion, introversion and happiness

- Hedonic treadmill

- Laurie Santos

- Mania

- Paradox of hedonism

- Psychological well-being

- Serotonin

- Thomas Traherne

References

- "happiness". Wolfram Alpha. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- Anand, P (2016). Happiness Explained. Oxford University Press.

- See definition section below.

- Feldman, Fred (2010). What is This Thing Called Happiness?. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199571178.001.0001. ISBN 9780199571178.

- The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy states that "An important project in the philosophy of happiness is simply getting clear on what various writers are talking about." https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/happiness/ Archived 2018-06-11 at the Wayback Machine

- "Two Philosophical Problems in the Study of Happiness". Archived from the original on 2018-10-14. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- Smith, Richard (2008). "The Long Slide to Happiness". Journal of Philosophy of Education. 42 (3–4): 559–573. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9752.2008.00650.x. Archived from the original on 2018-10-14. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- "How Universal is Happiness?" Ruut Veenhoven, Chapter 11 in Ed Diener, John F. Helliwell & Daniel Kahneman (Eds.) International Differences in Well-Being, 2010, Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 978-0-19-973273-9

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2018-10-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "particularly section 4". Archived from the original on 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- Dan Haybron (https://www.slu.edu/colleges/AS/philos/site/people/faculty/Haybron/ Archived 2019-08-30 at the Wayback Machine, http://www.happinessandwellbeing.org/project-team/ Archived 2018-10-12 at the Wayback Machine); "I would suggest that when we talk about happiness, we are actually referring, much of the time, to a complex emotional phenomenon. Call it emotional well-being. Happiness as emotional well-being concerns your emotions and moods, more broadly your emotional condition as a whole. To be happy is to inhabit a favorable emotional state.... On this view, we can think of happiness, loosely, as the opposite of anxiety and depression. Being in good spirits, quick to laugh and slow to anger, at peace and untroubled, confident and comfortable in your own skin, engaged, energetic and full of life." https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/04/13/happiness-and-its-discontents/ Archived 2018-10-12 at the Wayback Machine Haybron has also used the term thymic, by which he means 'overall mood state' in this context; https://philpapers.org/rec/HAYHAE Archived 2018-10-18 at the Wayback Machine Xavier Landes <https://www.sseriga.edu/landes-xavier Archived 2019-08-30 at the Wayback Machine> has described a similar concept of mood. https://www.satori.lv/article/kas-ir-laime Archived 2019-05-13 at the Wayback Machine

- "People don’t want to be happy the way I’ve defined the term – what I experience here and now. In my view, it’s much more important for them to be satisfied, to experience life satisfaction, from the perspective of ‘What I remember,’ of the story they tell about their lives."https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium.MAGAZINE-why-nobel-prize-winner-daniel-kahneman-gave-up-on-happiness-1.6528513 Archived 2018-10-08 at the Wayback Machine

- "Happy | Definition of happy in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Archived from the original on 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "HAPPINESS | meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". Archived from the original on 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- "The definition of happy". Archived from the original on 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- Graham, Michael C. (2014). Facts of Life: ten issues of contentment. Outskirts Press. pp. 6–10. ISBN 978-1-4787-2259-5.

- https://personal.eur.nl/veenhoven/Pub2010s/2012k-full.pdf Archived 2017-08-09 at the Wayback Machine, 1.1

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/happiness/ Archived 2018-06-11 at the Wayback Machine 2011, "‘Happiness’ is often used, in ordinary life, to refer to a short-lived state of a person, frequently a feeling of contentment: ‘You look happy today’; ‘I’m very happy for you’. Philosophically, its scope is more often wider, encompassing a whole life. And in philosophy it is possible to speak of the happiness of a person’s life, or of their happy life, even if that person was in fact usually pretty miserable. The point is that some good things in their life made it a happy one, even though they lacked contentment. But this usage is uncommon, and may cause confusion.' https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/well-being/ Archived 2018-10-25 at the Wayback Machine 2017

- “People don’t want to be happy the way I’ve defined the term – what I experience here and now. In my view, it’s much more important for them to be satisfied, to experience life satisfaction, from the perspective of ‘What I remember,’ of the story they tell about their lives.https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium.MAGAZINE-why-nobel-prize-winner-daniel-kahneman-gave-up-on-happiness-1.6528513

- See e.g. 'Can Happiness be Measured', Action for Happiness, http://www.actionforhappiness.org/why-happiness Archived 2018-10-18 at the Wayback Machine

- See Subjective well-being#Components of SWB

- The How of Happiness, Lyubomirsky, 2007

- Kashdan, Todd B.; Biswas-Diener, Robert; King, Laura A. (2008). "Reconsidering happiness: The costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia". The Journal of Positive Psychology. 3 (4): 219–233. doi:10.1080/17439760802303044.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-08-30. Retrieved 2019-08-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://www.satori.lv/article/kas-ir-laime Archived 2019-05-13 at the Wayback Machine Contact the author for English version

- "I am happy when I'm unhappy." Mark Baum character, The Big Short (film), https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/The_Big_Short_(film)#Mark_Baum Archived 2018-10-17 at the Wayback Machine

- "Surveying large numbers of Americans in one case, and what is claimed to be the first globally representative sample of humanity in the other, these studies found that income does indeed correlate substantially (.44 in the global sample), at all levels, with life satisfaction—strictly speaking, a “life evaluation” measure that asks respondents to rate their lives without saying whether they are satisfied. Yet the correlation of household income with the affect measures is far weaker: globally, .17 for positive affect, –.09 for negative affect; and in the United States, essentially zero above $75,000 (though quite strong at low income levels). If the results hold up, the upshot appears to be that income is pretty strongly related to life satisfaction, but weakly related to emotional well-being, at least above a certain threshold." Section 3.3, Happiness, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/happiness/#HedVerEmoSta Archived 2018-06-11 at the Wayback Machine

- "High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being", Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 21/9/10

- https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/182843/happiest-people-world-swiss-latin-americans.aspx

- "How does happiness come into this classification? For better or worse, it enters in three ways. It is sometimes used as a current emotional report – “How happy are you now?,” sometimes as a remembered emotion, as in “How happy were you yesterday?,” and very often as a form of life evaluation, as in “How happy are you with your life as a whole these days?” People answer these three types of happiness question differently, so it is important to keep track of what is being asked. The good news is that the answers differ in ways that suggest that people understand what they are being asked, and answer appropriately." John Helliwell and Shun Yang, p11, World Happiness Report 2012 http://worldhappiness.report/ed/2012/ Archived 2016-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "Some have argued that it is misleading to use ‘happiness’ as a generic term to cover subjective well-being more generally. While ‘subjective well-being’ is more precise, it simply does not have the convening power of ‘happiness’. The main linguistic argument for using happiness in a broader generic role is that happiness plays two important roles within the science of well-being, appearing once as a prototypical positive emotion and again as part of a cognitive life evaluation question. This double use has sometimes been used to argue that there is no coherent structure to happiness responses. The converse argument made in the World Happiness Reports is that this double usage helps to justify using happiness in a generic role, as long as the alternative meanings are clearly understood and credibly related. Evidence from a growing number of large scale surveys shows that the answers to questions asking about the emotion of happiness differ from answers to judgmental questions asking about a person’s happiness with life as a whole in exactly the ways that theory would suggest. Answers to questions about the emotion of happiness relate well to what is happening at the moment. Evaluative answers, in response to questions about life as a whole, are supported by positive emotions, as noted above, but also driven much more, than are answers to questions about emotions, by a variety of life circumstances, including income, health and social trust." John F. Helliwell and others, World Happiness Report, 2015, quoted in What's Special About Happiness as a Social Indicator? John F. Helliwell, Published online: 25 February 2017, Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2017.

- MacIntyre, Alasdair (1998). A Short History of Ethics (Second ed.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. p. 167.

- Mill, John Stuart (1879). Utilitarianism. Longmans, Green, and Co.

- "Nietzsche's Moral and Political Philosophy". stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-01-12. Retrieved 2015-08-10.

- "Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 2015-08-15. Retrieved 2015-08-10.

- McMahon, Darrin M. (2004). "From the happiness of virtue to the virtue of happiness: 400 B.C. – A.D. 1780". Daedalus. 133 (2): 5–17. doi:10.1162/001152604323049343. JSTOR 20027908.

- Hornsey, Matthew J.; Bain, Paul G.; Harris, Emily A.; Lebedeva, Nadezhda; Kashima, Emiko S.; Guan, Yanjun; González, Roberto; Chen, Sylvia Xiaohua; Blumen, Sheyla (2018). "How Much is Enough in a Perfect World? Cultural Variation in Ideal Levels of Happiness, Pleasure, Freedom, Health, Self-Esteem, Longevity, and Intelligence" (PDF). Psychological Science (Submitted manuscript). 29 (9): 1393–1404. doi:10.1177/0956797618768058. PMID 29889603. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-12-19. Retrieved 2018-11-02.

- See the work of Jeanne Tsai

- See Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness#Meaning of "happiness" ref. the meaning of the US Declaration of Independence phrase

- Joshanloo, Mohsen; Weijers, Dan (2014). "Aversion to Happiness Across Cultures: A Review of Where and Why People are Averse to Happiness". Journal of Happiness Studies. 15 (3): 717–735. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9489-9.

- "Study sheds light on how cultures differ in their happiness beliefs". Archived from the original on 2018-10-10. Retrieved 2018-10-10.

- "In Buddhism, There Are Seven Factors of Enlightenment. What Are They?". About.com Religion & Spirituality. Archived from the original on 2016-04-09. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- "Buddhist studies for primary and secondary students, Unit Six: The Four Immeasurables". Buddhanet.net. Archived from the original on 2003-02-27. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- Bhikkhu, Thanissaro (1999). "A Guided Meditation". Archived from the original on 2006-06-13. Retrieved 2006-06-06.

- Levine, Marvin (2000). The Positive Psychology of Buddhism and Yoga : Paths to a Mature Happiness. Lawrence Erlbaum. ISBN 978-0-8058-3833-6.

- Chan, Wing-tsit (1963). A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01964-2.

- Yanklowitz, Shmuly. "Judaism's value of happiness living with gratitude and idealism." Archived 2014-11-12 at the Wayback Machine Bloggish. The Jewish Journal. March 9, 2012.

- Breslov.org. Archived November 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Accessed November 11, 2014.

- Aquinas, Thomas. "Question 3. What is happiness". Summa Theologiae. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007.

- "Summa Theologica: Man's last end (Prima Secundae Partis, Q. 1)". Newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 2011-11-05. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- "Summa Theologica: Secunda Secundae Partis". Newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 2013-05-18. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- "Summa Theologica: What is happiness (Prima Secundae Partis, Q. 3)". Newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 2012-01-09. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- "Catholic Encyclopedia: Happiness". newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 2012-05-01. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- Algoe, Sara B.; Haidt, Jonathan (2009). "Witnessing excellence in action: the 'other-praising' emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration". The Journal of Positive Psychology. 4 (2): 105–27. doi:10.1080/17439760802650519. PMC 2689844. PMID 19495425.

- Kahneman, Daniel; Riis, Jason (2005). "Living, and thinking about it: two perspectives on life" (PDF). In Huppert, Felicia A; Baylis, Nick; Keverne, Barry (eds.). The science of well-being. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198567523.003.0011. ISBN 978-0-19-856752-3. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Deci, Edward L.; Ryan, Richard M. (2006). "Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: an introduction". Journal of Happiness Studies. 9 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1.

- Cosmides, Leda; Tooby, John (2000). "Evolutionary Psychology and the Emotions". In Lewis, Michael; Haviland-Jones, Jeannette M. (eds.). Handbook of emotions (2 ed.). New York [u.a.]: Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-57230-529-8. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- Lewis, Michael (2016-07-12). "Self-Conscious emotions". In Barrett, Lisa Feldman; Lewis, Michael; Haviland-Jones, Jeannette M. (eds.). Handbook of Emotions (Fourth ed.). Guilford Publications. p. 793. ISBN 978-1-4625-2536-2. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Marano, Hara Estroff (1 November 1995). "At Last—a Rejection Detector!". Psychology Today. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Seligman, Martin E. P. (2004). "Can happiness be taught?". Daedalus. 133 (2): 80–87. doi:10.1162/001152604323049424. JSTOR 20027916.

- Inglehart, Ronald; Foa, Roberto; Peterson, Christopher; Welzel, Christian (July 2008). "Development, Freedom, and Rising Happiness: A Global Perspective (1981–2007)". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 3 (4): 264–285. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00078.x.

- Inglehart, Ronald F. (2018). Cultural Evolution: People's Motivations Are Changing, and Reshaping the World. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108613880. ISBN 978-1-108-61388-0.

- Wallis, Claudia (2005-01-09). "Science of Happiness: New Research on Mood, Satisfaction". TIME. Archived from the original on November 15, 2010. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- Bolier, Linda; Haverman, Merel; Westerhof, Gerben J; Riper, Heleen; Smit, Filip; Bohlmeijer, Ernst (8 February 2013). "Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies". BMC Public Health. 13 (1): 119. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-119. PMC 3599475. PMID 23390882.

- "40 Scientifically Proven Ways To Be Happier". 2015-02-19. Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2018-02-12.

- Tokumitsu, Miya (June 2017). "Did the Fun Work?". The Baffler. 35. Archived from the original on 2019-07-25. Retrieved 2019-02-03.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 22, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Lyubomirsky, Sonja; Lepper, Heidi S. (February 1999). "A Measure of Subjective Happiness: Preliminary Reliability and Construct Validation". Social Indicators Research. 46 (2): 137–55. doi:10.1023/A:1006824100041. JSTOR 27522363.

- "Rutgers University-Camden |". Archived from the original on 2012-04-15. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- Watson, David; Clark, Lee A.; Tellegen, Auke (1988). "Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 54 (6): 1063–70. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. PMID 3397865.

- Watson, David; Clark, Lee Anna (1994). "The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Expanded Form". Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences Publications. The University of Iowa. doi:10.17077/48vt-m4t2. Archived from the original on 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- "SWLS Rating Form". tbims.org. Archived from the original on 2012-04-16. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- Diener, Ed; Emmons, Robert A.; Larsen, Randy J.; Griffin, Sharon (1985). "The Satisfaction With Life Scale". Journal of Personality Assessment. 49 (1): 71–75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. PMID 16367493.

- Levin, K. A.; Currie, C. (2014). "Reliability and Validity of an Adapted Version of the Cantril Ladder for Use with Adolescent Samples". Social Indicators Research. 119 (2): 1047–1063. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0507-4.

- "FAQ". Archived from the original on 2018-12-31. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- https://www.gallup.com/analytics/248906/gallup-global-emotions-report-2019.aspx Gallup Global Emotions 2019

- Helliwell, John; Layard, Richard; Sachs, Jeffrey, eds. (2012). World Happiness Report. ISBN 978-0-9968513-0-5. Archived from the original on 2016-07-18. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- "Measuring National Well-being: Life in the UK, 2012". Ons.gov.uk. 2012-11-20. Archived from the original on 2013-03-26. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- "The Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan" (PDF). National Council. Royal Government of Bhutan. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-16. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Kelly, Annie (1 December 2012). "Gross national happiness in Bhutan: the big idea from a tiny state that could change the world". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 2018-04-05. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- Baumeister, Roy F.; Vohs, Kathleen D.; Aaker, Jennifer L.; Garbinsky, Emily N. (November 2013). "Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life". The Journal of Positive Psychology. 8 (6): 505–516. doi:10.1080/17439760.2013.830764.

- Costa, Paul T.; McCrae, Robert R.; Zonderman, Alan B. (August 1987). "Environmental and dispositional influences on well-being: Longitudinal follow-up of an American national sample". British Journal of Psychology. 78 (3): 299–306. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1987.tb02248.x. PMID 3620790.

- Gudrais, Elizabeth (November–December 2016). "Can Happiness Make You Healthier?". Harvard Magazine. Archived from the original on 2017-10-16. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- Toichi, Motomi; Yoshimura, Sayaka; Sawada, Reiko; Kubota, Yasutaka; Uono, Shota; Kochiyama, Takanori; Sato, Wataru (2015-11-20). "The structural neural substrate of subjective happiness". Scientific Reports. 5: 16891. Bibcode:2015NatSR...516891S. doi:10.1038/srep16891. PMC 4653620. PMID 26586449.

- "Positive Emotion and Psychopathology Lab - Director Dr. June Gruber". Archived from the original on 2018-10-10. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/jan/04/trying-to-be-happy-could-make-you-miserable-study-finds

- Adler, Jonathan M.; Hershfield, Hal E. (2012). "Mixed Emotional Experience is Associated with and Precedes Improvements in Psychological Well-Being". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e35633. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...735633A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035633. PMC 3334356. PMID 22539987.

- Also https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256542618_When_Feeling_Bad_Can_Be_Good_Mixed_Emotions_Benefit_Physical_Health_Across_Adulthood Archived 2019-01-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Baumeister, Roy F.; Vohs, Kathleen D.; Aaker, Jennifer L.; Garbinsky, Emily N. (2013). "Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life". The Journal of Positive Psychology. 8 (6): 505–516. doi:10.1080/17439760.2013.830764.

- Abe, Jo Ann A. (2016). "A longitudinal follow-up study of happiness and meaning-making". The Journal of Positive Psychology. 11 (5): 489–498. doi:10.1080/17439760.2015.1117129.

- "The Differences between Happiness and Meaning in Life". Archived from the original on 2018-11-14. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- Hornsey, Matthew J.; Bain, Paul G.; Harris, Emily A.; Lebedeva, Nadezhda; Kashima, Emiko S.; Guan, Yanjun; González, Roberto; Chen, Sylvia Xiaohua; Blumen, Sheyla (2018). "How Much is Enough in a Perfect World? Cultural Variation in Ideal Levels of Happiness, Pleasure, Freedom, Health, Self-Esteem, Longevity, and Intelligence" (PDF). Psychological Science. 29 (9): 1393–1404. doi:10.1177/0956797618768058. PMID 29889603.

- Springer (17 March 2014). "Study sheds light on how cultures differ in their happiness beliefs". Science X Network. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Freud, S. Civilization and its discontents. Translated and edited by James Strachey, Chapter II. New York: W. W. Norton. [Originally published in 1930].

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. (1964). "The Lost Meaning of "The Pursuit of Happiness"". The William and Mary Quarterly. 21 (3): 325–27. doi:10.2307/1918449. JSTOR 1918449.

- Fountain, Ben (17 September 2016). "Two American Dreams: how a dumbed-down nation lost sight of a great idea". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2016-11-23. Retrieved 2017-01-19.

- Frey, Bruno S.; Alois Stutzer (2001). Happiness and Economics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-06998-2.

- "In Pursuit of Happiness Research. Is It Reliable? What Does It Imply for Policy?". The Cato institute. 2007-04-11. Archived from the original on 2011-02-19. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- "Wealth and happiness revisited Growing wealth of nations does go with greater happiness" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-10-16. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- Leonhardt, David (2008-04-16). "Maybe Money Does Buy Happiness After All". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2009-04-24. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- "Economic Growth and Subjective Well-Being: Reassessing the Easterlin Paradox" (PDF). bpp.wharton.upenn.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2012.

- Akst, Daniel (2008-11-23). "Boston.com". Boston.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-13. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- In Pursuit of Happiness Research. Is It Reliable? What Does It Imply for Policy? Archived 2011-02-19 at the Wayback Machine The Cato institute. April 11, 2007

- The Scientist's Pursuit of Happiness Archived February 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Policy, Spring 2005.

- Radcliff, Benjamin (2013) The Political Economy of Human Happiness (New York: Cambridge University Press). See also this collection of full-text peer reviewed scholarly articles on this subject by Radcliff and colleagues (from "Social Forces," "The Journal of Politics," and "Perspectives on Politics," among others) Archived 2015-07-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Michael Krassa (14 May 2014). "Does a higher minimum wage make people happier?". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2015-07-07. Retrieved 2017-08-29.

- Weiner, Eric J. (2007-11-13). "Four months of boom, bust, and fleeing foreign credit". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 22, 2007.

- Coercive regulation and the balance of freedom Archived 2009-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, Edward Glaeser, Cato Unbound 11.5.2007

- Mental health and relationships 'key to happiness' Archived 2018-03-16 at the Wayback Machine BBC

- Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi 2000.

Further reading

- Anand Paul "Happiness Explained: What Human Flourishing Is and What We Can Do to Promote It", Oxford: Oxford University Press 2016. ISBN 0-19-873545-6

- Michael Argyle "The psychology of happiness", 1987

- Boehm, J.K.; Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). "Does Happiness Promote Career Success?". Journal of Career Assessment. 16 (1): 101–16. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.378.6546. doi:10.1177/1069072707308140.

- Norman M. Bradburn "The structure of psychological well-being", 1969

- C. Robert Cloninger, Feeling Good: The Science of Well-Being, Oxford, 2004.

- Gregg Easterbrook "The progress paradox – how life gets better while people feel worse", 2003

- Michael W. Eysenck "Happiness – facts and myths", 1990

- Daniel Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness, Knopf, 2006.

- Carol Graham "Happiness Around the World: The Paradox of Happy Peasants and Miserable Millionaires", OUP Oxford, 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-954905-4

- W. Doyle Gentry "Happiness for dummies", 2008

- James Hadley, Happiness: A New Perspective, 2013, ISBN 978-1-4935-4526-1

- Joop Hartog & Hessel Oosterbeek "Health, wealth and happiness", 1997

- Hills P., Argyle M. (2002). "The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: a compact scale for the measurement of psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences". Psychological Wellbeing. 33 (7): 1073–82. doi:10.1016/s0191-8869(01)00213-6.

- Robert Holden "Happiness now!", 1998

- Barbara Ann Kipfer, 14,000 Things to Be Happy About, Workman, 1990/2007, ISBN 978-0-7611-4721-3.

- Neil Kaufman "Happiness is a choice", 1991

- Stefan Klein, The Science of Happiness, Marlowe, 2006, ISBN 1-56924-328-X.

- Koenig HG, McCullough M, & Larson DB. Handbook of religion and health: a century of research reviewed (see article). New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

- McMahon, Darrin M., Happiness: A History, Atlantic Monthly Press; 2005. ISBN 0-87113-886-7

- McMahon, Darrin M., The History of Happiness: 400 B.C. – A.D. 1780, Daedalus journal, Spring 2004.

- Richard Layard, Happiness: Lessons From A New Science, Penguin, 2005, ISBN 978-0-14-101690-0.

- Luskin, Frederic, Kenneth R. Pelletier, Dr. Andrew Weil (Foreword). "Stress Free for Good: 10 Scientifically Proven Life Skills for Health and Happiness." 2005

- James Mackaye "Economy of happiness", 1906

- Desmond Morris "The nature of happiness", 2004

- David G. Myers, Ph.D., The Pursuit of Happiness: Who is Happy – and Why, William Morrow and Co., 1992, ISBN 0-688-10550-5.

- Niek Persoon "Happiness doesn't just happen", 2006

- Benjamin Radcliff The Political Economy of Human Happiness (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- Ben Renshaw "The secrets of happiness", 2003

- Fiona Robards, "What makes you happy?" Exisle Publishing, 2014, ISBN 978-1-921966-31-6

- Bertrand Russell "The conquest of happiness", orig. 1930 (many reprints)

- Martin E.P. Seligman, Authentic Happiness, Free Press, 2002, ISBN 0-7432-2298-9.

- Alexandra Stoddard "Choosing happiness – keys to a joyful life", 2002

- Władysław Tatarkiewicz, Analysis of Happiness, The Hague, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1976

- Elizabeth Telfer "Happiness : an examination of a hedonistic and a eudaemonistic concept of happiness and of the relations between them...", 1980

- Ruut Veenhoven "Bibliography of happiness – world database of happiness : 2472 studies on subjective appreciation of life", 1993

- Ruut Veenhoven "Conditions of happiness", 1984

- Joachim Weimann, Andreas Knabe, and Ronnie Schob, eds. Measuring Happiness: The Economics of Well-Being (MIT Press; 2015) 206 pages

- Eric G. Wilson "Against Happiness", 2008

- Articles and videos

- Journal of Happiness Studies, International Society for Quality-of-Life Studies (ISQOLS), quarterly since 2000, also online

- A Point of View: The pursuit of happiness (January 2015), BBC News Magazine

- Srikumar Rao: Plug into your hard-wired happiness – Video of a short lecture on how to be happy

- Dan Gilbert: Why are we happy? – Video of a short lecture on how our "psychological immune system" lets us feel happy even when things don't go as planned.

- TED Radio Hour: Simply Happy – various guest speakers, with some research results

External links

- History of Happiness – concise survey of influential theories

- The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry "Pleasure" – ancient and modern philosophers' and neuroscientists' approaches to happiness

- The World Happiness Forum promotes dialogue on tools and techniques for human happiness and wellbeing.

- Action For Happiness is a UK movement committed to building a happier society

- Improving happiness through humanistic leadership – University of Bath, UK

- The World Database of Happiness – a register of scientific research on the subjective appreciation of life.

- Oxford Happiness Questionnaire – Online psychological test to measure your happiness.

- Track Your Happiness – research project with downloadable app that surveys users periodically and determines personal factors

- Pharrell Williams – Happy (Official Music Video) added to YouTube by P. Williams: i Am Other – Retrieved 2015-11-21

- Four Levels of Happiness – A modern take on the Greco-Christian understanding of happiness in 4 levels.