Politics of Spain

The politics of Spain takes place under the framework established by the Constitution of 1978. Spain is established as a social and democratic sovereign country[1] wherein the national sovereignty is vested in the people, from which the powers of the state emanate.[1]

.svg.png) | |

| Polity type | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

|---|---|

| Constitution | Constitution of Spain |

| Legislative branch | |

| Name | General Courts |

| Type | Bicameral |

| Meeting place | Palace of the Senate Palace of the Courts |

| Upper house | |

| Name | Senate |

| Presiding officer | Pilar Llop, President of the Senate |

| Lower house | |

| Name | Congress of Deputies |

| Presiding officer | Meritxell Batet, President of the Congress of Deputies |

| Executive branch | |

| Head of State | |

| Title | Monarch |

| Currently | Felipe VI |

| Appointer | Hereditary |

| Head of Government | |

| Title | Prime Minister |

| Currently | Pedro Sánchez |

| Appointer | Monarch |

| Cabinet | |

| Name | Council of Ministers |

| Current cabinet | Sánchez II Government |

| Leader | Prime Minister |

| Deputy leader | First Deputy Prime Minister |

| Appointer | Monarch |

| Headquarters | Palace of Moncloa |

| Judicial branch | |

| Name | Judiciary of Spain |

| Courts | High Courts of Justice |

| Supreme Court | |

| Chief judge | Carlos Lesmes |

| Seat | Convent of the Salesas Reales |

| National Court | |

| Chief judge | José Ramón Navarro |

.svg.png) |

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Spain |

|

Constitution

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Related topics

|

The form of government in Spain is a parliamentary monarchy,[1] that is, a social representative democratic constitutional monarchy in which the monarch is the head of state, while the prime minister—whose official title is "President of the Government"—is the head of government. Executive power is exercised by the Government, which is integrated by the prime minister, the deputy prime ministers and other ministers, which collectively form the Cabinet, or Council of Ministers. Legislative power is vested in the Cortes Generales (General Courts), a bicameral parliament constituted by the Congress of Deputies and the Senate. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature, administering justice on behalf of the King by judges and magistrates. The Supreme Court of Spain is the highest court in the nation, with jurisdiction in all Spanish territories, superior to all in all affairs except constitutional matters, which are the jurisdiction of a separate court, the Constitutional Court.

Spain's political system is a multi-party system, but since the 1990s two parties have been predominant in politics, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and the People's Party (PP). Regional parties, mainly the Basque Nationalist Party (EAJ-PNV), from the Basque Country, and Convergence and Union (CiU) and the Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC), from Catalonia, have also played key roles in Spanish politics. Members of the Congress of Deputies are selected through proportional representation, and the government is formed by the party or coalition that has the confidence of the Congress, usually the party with the largest number of seats. Since the Spanish transition to democracy, there have not been coalition governments; when a party has failed to obtain absolute majority, minority governments have been formed.

Regional government functions under a system known as the state of autonomies, a highly decentralized system of administration (systematically ranked 2nd in the world after Germany at the Regional Authority Index, since 1998).[2] Initially framed as a kind of "assymmetrical federalism" for the regions styled as "historic nationalities", it has evolved in practice into an approach that gives way to a devolution of powers for all regions, widely known as "coffee for everyone".[3] Exercising the right to self-government granted by the constitution, the "nationalities and regions" have been constituted as 17 autonomous communities and two autonomous cities. The form of government of each autonomous community and autonomous city is also based on a parliamentary system, in which executive power is vested in a "president" and a Council of Ministers, elected by and responsible to a unicameral legislative assembly.

The Economist Intelligence Unit rated Spain as a "full democracy" in 2016.[4]

The Crown

The King and his functions

The Spanish monarch, currently, Felipe VI, is the head of the Spanish State, symbol of its unity and permanence, who arbitrates and moderates the regular function of government institutions, and assumes the highest representation of Spain in international relations, especially with those who are part of its historical community.[5] His title is King of Spain, although he can use all other titles of the Crown. The Crown, as a symbol of the nation's unity, has a two-fold function. First, it represents the unity of the State in the organic separation of powers; hence he appoints the prime ministers and summons and dissolves the Parliament, among other responsibilities. Secondly, it represents the Spanish State as a whole in relation to the autonomous communities, whose rights he is constitutionally bound to respect.[6]

The King is proclaimed by the Cortes Generales — the Parliament — and must take an oath to carry out his duties faithfully, to obey the constitution and all laws and to ensure they are obeyed, and to respect the rights of the citizens, as well as the rights of the autonomous communities.[7]

According to the Constitution of Spain, it is incumbent upon the King:[8][9] to sanction and promulgate laws; to summon and dissolve the Cortes Generales (the Parliament) and to call elections; to call a referendum under the circumstances provided in the constitution; to propose a candidate for prime minister, and to appoint or remove him from office, as well as other ministers; to issue the decrees agreed upon by the Council of Ministers; to confer civil and military positions, and to award honors and distinctions; to be informed of the affairs of the State, presiding over the meetings of the Council of Ministers whenever opportune; to exercise supreme command of the Spanish Armed Forces, to exercise the right to grant pardons, in accordance to the law; and to exercise the High Patronage of the Royal Academies. All ambassadors and other diplomatic representatives are accredited by him, and foreign representatives in Spain are accredited to him. He also expresses the State's assent to entering into international commitments through treaties; and he declares war or makes peace, following the authorization of the Cortes Generales.

In practical terms, his duties are mostly ceremonial, and constitutional provisions are worded in such a way as to make clear the strict neutral and apolitical nature of his role.[10][11] In fact, the Fathers of the Constitution made careful use of the expressions "it is incumbent upon of the King", deliberately omitting other expressions such as "powers", "faculties" or "competences", thus eliminating any notion of monarchical prerogatives within the parliamentary monarchy.[12] In the same way, the King does not have supreme liberty in the exercise of the aforementioned functions; all of these are framed, limited or exercised "according to the constitution and laws", or following requests of the executive or authorizations of the legislature.[12]

The king is the commander-in-chief of the Spanish Armed Forces, but has only symbolic, rather than actual, authority over the Spanish military.[11] Nonetheless, the king's function as the commander-in-chief and symbol of national unity have been exercised, most notably in the military coup of 23 February 1981, where King Juan Carlos I addressed the country on national television in military uniform, denouncing the coup and urging the maintenance of the law and the continuance of the democratically elected government, thus defusing the uprising.[11]

Succession line

The Spanish Constitution, promulgated in 1978, established explicitly that Juan Carlos I is the legitimate heir of the historical dynasty.[13] This statement served two purposes. First, it established that the position of the King emanates from the constitution, the source from which its existence is legitimized democratically. Secondly, it reaffirmed the dynastic legitimacy of the person of Juan Carlos I, not so much to end old historical dynastic struggles — namely those historically embraced by the Carlist movement — but as a consequence of the renunciation to all rights of succession that his father, Juan de Borbón y Battenberg, made in 1977.[14] Juan Carlos I was constitutional king of Spain from 1978 to 2014. He abdicated in favor of his son Felipe VI.

The constitution also establishes that the monarchy is hereditary following a "regular order of primogeniture and representation: earlier line shall precede older; within the same line, closer degree shall precede more distant; within the same degree, male shall precede female; and within the same sex, older shall precede the younger".[13] What this means in practice, is that the Crown is passed to the firstborn, who would have preference over his siblings and cousins; women can only accede to the throne provided they do not have any older or younger brothers; and finally "regular order of representation" means that grandchildren have preference over the deceased King's parents, uncles or siblings.[14] Finally, if all possible rightful orders of primogeniture and representation have been exhausted, then the General Courts will select a successor in the way that best suits the interest of Spain. The heir presumptive or heir apparent holds the title of Prince or Princess of Asturias. The current heir presumptive is princess Leonor de Borbón.

Legislature

Legislative power is vested in the Spanish Parliament, the Cortes Generales. (Literally "General Courts",[15] but rarely translated as such. "Cortes" has been the historical and constitutional name used since Medieval Times. The qualifier "General", added in the Constitution of 1978, implies the nationwide character of the Parliament, since the legislatures of some autonomous communities are also labeled "Cortes").[16] The Cortes Generales are the supreme representatives of the Spanish people. This legislature is bicameral, integrated by the Congress of Deputies (Spanish: Congreso de los Diputados) and the Senate (Spanish: Senado). The General Courts exercise the legislative power of the State, approving the budget and controlling the actions of the government. As in most parliamentary systems, more legislative power is vested in the lower chamber, the Congress of the Deputies.[11] The Speaker of Congress, known as "president of the Congress of Deputies" presides a joint-session of the Cortes Generales.

Each chamber of the Cortes Generales meets at separate precincts, and carry out their duties separately, except for specific important functions, in which case they meet in a joint session. Such functions include the elaboration of laws proposed by the executive ("the Government"), by one of the chambers, by an autonomous community, or through popular initiative; and the approval or amendment of the nation's budget proposed by the prime minister.[10]

The Congress of Deputies

_14.jpg)

The Congress of Deputies must be integrated by a minimum of 300 and a maximum of 400 deputies (members of parliament) — currently 350 — elected by universal, free, equal, direct and secret suffrage, to four-year terms or until the dissolution of the Cortes Generales. The voting system used is that of proportional representation with closed party lists following D'Hondt method in which the province forms a constituency or electoral circumscription and must be assigned a minimum of 2 deputies; the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla, are each assigned one deputy.

The Congress of Deputies can initiate legislation, and they also have the power to ratify or reject the decree laws adopted by the executive. They also elect, via a vote of investiture, the prime minister (the "president of the Government"), before he or she can be formally sworn to office by the King.[10] The Congress of Deputies may adopt a motion of censure whereby it can vote out the prime minister by absolute majority. On the other hand, the prime minister may request at any time a vote of confidence from the Congress of Deputies. If he or she fails to obtain it, then the Cortes Generales are dissolved, and new elections are called.

Senate

The upper chamber is the Senate. It is nominally the chamber of territorial representation. Four senators are elected for each province, with the exception of the insular provinces, in which the number of senator varies: three senators are elected for each of the three major islands — Gran Canaria, Mallorca and Tenerife — and one senator for Ibiza-Formentera, Menorca, Fuerteventura, La Gomera, El Hierro, Lanzarote and La Palma. The autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla each elect two senators.

In addition, the legislative assembly of each autonomous community designates one senator, and another for each one million inhabitants. This designation must follow proportional representation. For the 2011 elections, this system allowed for 266 senators, 208 of which were elected and 58 of which were designated by the autonomous communities. Senators serve for four-year terms or until the dissolution of the Cortes Generales. Even though the constitution explicitly refers to the Senate as the chamber of territorial representation, as seen from the numbers before, only one-fifth of the senators actually represent the autonomous communities.[11] Since the constitution allowed for the creation of autonomous communities, but the process itself was embryonic in nature — they were formed after the promulgation of the constitution, and the outcome was unpredictable — the constituent assembly chose the province as the basis for territorial representation.[17]

The Senate has less power than the Congress of Deputies: it can veto legislation, but its veto can be overturned by an absolute majority of the Congress of Deputies. Its only exclusive power concerns the autonomous communities, thus in a way performing a function in line with its nature of "territorial representation". By an overall majority, the Senate is the institution that authorizes the Government to adopt measures to enforce an autonomous community's compliance with its constitutional duties when it has failed to do so.

For the first time ever, on Friday, 27 October 2017, the senate voted, by majority, to invoke article 155 of the constitution, which gave the central government the power to remove the government of the autonomous region of Cataluña for acting against the constitution of 1978 by having called an illegal referendum on 1 October.

Executive

The Government and the Council of Ministers

At the national level, executive power in Spain is exercised only by "the Government". (The King is the head of state, but the constitution does not attribute to him any executive faculties). The Government is composed by a prime minister, known as the "president of the Government" (Spanish: presidente del gobierno), one or more deputy prime ministers, known as "vice-presidents of the Government" (Spanish: vicepresidentes del gobierno) and all other ministers. The collegiate body composed by the prime minister, the deputy prime ministers, and all other ministers is called the Council of Ministers. The Government is in charge of both domestic and foreign policy, as well as defense and economic policies.[11] As of 2 June 2018, the prime minister of Spain is Pedro Sánchez.

The constitution[18] establishes that after elections, the King, after consulting with all political groups represented in the Congress of Deputies, proposes a candidate to the "presidency of the Government" or prime ministership through the Speaker of Congress. The candidate then presents the political program of his or her government requesting the Congress's confidence. If the Congress grants him confidence by absolute majority, the King then nominates him formally as "president of the Government"; if he or she fails to obtain absolute majority, the Congress waits 48 hours to vote again, in which case, a simple majority suffices. If he or she fails again, then the King presents other candidates until one gains confidence. However, if after two months no candidate has obtained it, then the King dissolves the Cortes Generales and calls for new elections with the endorsement of the Speaker of Congress.[18] In practice, the candidate has been the leader of the party that obtained the largest number of seats in the Congress. Since the constitution of 1978 came into effect, there have not been any coalition governments, even if the party with the largest number of seats has failed to obtained absolute majority, though in such cases the party in government has had to rely on the support of minority parties to gain confidence and to approve the State's budgets.

After the candidate obtains the confidence of the Congress of Deputies, he is appointed by the King as prime minister in a ceremony of inauguration in which he is sworn at the Audience Hall of the Palace of Zarzuela — the residence of the King — and in presence of the Major Notary of the Kingdom. The candidate takes the oath of office over an open copy of the Constitution next to a Bible. The oath of office used is: "I swear/promise to faithfully carry out the duties of the position of president of the Government with loyalty to the King; to obey and enforce the Constitution as the fundamental law of the State, as well as to keep in secret the deliberations of the Council of Ministers".

The prime ministers proposes the deputy prime ministers and the other ministers, which are then appointed by the King. The number and the scope of competences of each of the Ministries is established by the prime minister. Ministries are usually created to cover one or several similar sectors of government from an administrative function. Once formed, the Government meets as the "Council of Ministers", usually every Friday at the Palace of Moncloa in Madrid, the official residence of the prime minister who presides over the meetings, even though, on exceptions they can be held in any other Spanish city. Also, on exceptions, the meeting can be presided by the King of Spain, by request of the prime minister, in which case, the Council informs the King of the State's affairs.

From 7 June 2018, the current government consists of the Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, the Deputy Prime Minister, María del Carmen Calvo Poyato, and 17 ministers:

- Ministry of the Presidency, Relations with the Cortes and Equality - María del Carmen Calvo Poyato

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs, European Union and Cooperation - Josep Borrell i Fontelles

- Ministry of Justice - Dolores Delgado García

- Ministry of Defence - Margarita Robles Fernández

- Ministry of Finance - María Jesús Montero Cuadrado

- Ministry of the Interior - Fernando Grande-Marlaska Gómez

- Ministry of Public Works - José Luis Ábalos Meco

- Ministry of Education and Vocational Training - María Isabel Celaá Diéguez

- Ministry of Labour, Migrations and Social Security - Magdalena Valerio Cordero

- Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism - María Reyes Maroto Illera

- Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food - Luis Planas Puchades

- Ministry of Territorial Policy and Civil Service - Meritxell Batet Lamaña

- Ministry for the Ecological Transition - Teresa Ribera Rodríguez

- Ministry of Culture and Sport - José Guirao Cabrera

- Ministry of Economy and Enterprise - Nadia Calviño Santamaría

- Ministry of Health, Consumer Affairs and Social Welfare - María Luisa Carcedo

- Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities - Pedro Francisco Duque Duque

The Council of State

The constitution also established the Council of State, a supreme advisory council to the Spanish government.[19] Though the body has existed intermittently since medieval times, its current composition and the nature of its work are defined in the constitution and subsequent laws that have been published, the most recent in 2004. It is currently composed by a president, nominated by the Council of Ministers, several ex officio councillors — former prime ministers of Spain, directors or presidents of the Royal Spanish Academy, the Royal Academy of Jurisprudence and Legislation, the Royal Academy of History, the Social and Economic Council, the Attorney General of the State, the Chief of Staff, the Governor of the Bank of Spain, the Director of the Juridical Service of the State, and the presidents of the General Commission of Codification and Law — several permanent councilors, appointed by decree, and no more than ten elected councilors in addition to the Council's Secretary General. The Council of State serves only as an advisory body, that can give non-binding opinions upon request and to propose an alternative solution to the problem presented.

Judiciary

The Judiciary in Spain is integrated by judges and magistrates who administer justice in the King's name.[20] The Judiciary is composed of different courts depending on the jurisdictional order and what is to be judged. The highest ranking court of the Spanish judiciary is the Supreme Court (Spanish: Tribunal Supremo), with jurisdiction in all Spain, superior in all matters except in constitutional guarantees. The Supreme Court is headed by a president, nominated by the King, proposed by the General Council of the Judiciary. This institution is the governing body of the Judiciary, integrated by the president of the Supreme court, twenty members appointed by the King for a five-year term, among whom there are twelve judges and magistrates of all judicial categories, four members nominated by the Congress of Deputies, and four by the Senate, elected in both cases by three-fifths of their respective members. They are to be elected from among lawyers and jurists of acknowledged competence and with over 15 years of professional experience.

The Constitutional Court (Spanish: Tribunal Constitucional) has jurisdiction over all Spain, competent to hear appeals against the alleged unconstitutionality of laws and regulations having the force of law, as well as individual appeals for protection (recursos de amparo) against violation of the rights and liberties granted by the constitution.[21] It consists of 12 members, appointed by the King, 4 of which are proposed by the Congress of Deputies by three-fifths of its members, 4 of which are proposed by the Senate by three-fifths of its members as well, 2 proposed by the executive and 2 proposed by the General Council of the Judiciary. They are to be renowned magistrates and prosecutors, university professors, public officials or lawyers, all of them jurists with recognized competence or standing and more than 15 years of professional experience.

Regional government

The second article of the constitution declares the Spanish nation is the common and indivisible homeland of all Spaniards, which is integrated by nationalities and regions to which the constitution recognizes and guarantees the right to self-government.[22] Since the constitution of 1978 came into effect, these nationalities and regions progressively acceded to self-government and were constituted into 17 autonomous communities. In addition, two autonomous cities were constituted on the coast of North Africa. This administrative and political territorial division is known as the "State of Autonomies". Though highly decentralized, Spain is not a federation since the nation — as represented in the central institutions of government — retains full sovereignty.

The State, that is, the central government, has progressively and asymmetrically devolved or transferred power and competences to the autonomous communities after the constitution of 1978 came into effect. Each autonomous community is governed by a set of institutions established in its own Statute of Autonomy. The Statute of Autonomy is the basic organic institutional law, approved by the legislature of the community itself as well as by the Cortes Generales, the Spanish Parliament. The Statutes of Autonomy establish the name of the community according to its historical identity; the delimitation of its territory; the name, organization and seat of the autonomous institutions of government; and the competences that they assume and the foundations for their devolution or transfer from the central government.

All autonomous communities have a parliamentary form of government, with a clear separation of powers. Their legislatures represent the people of the community, exercising legislative power within the limits set forth in the constitution of Spain and the degree of devolution that the community has attained. Even though the central government has progressively transferred roughly the same amount of competences to all communities, devolution is still asymmetrical. More power was devolved to the so-called "historical nationalities" — the Basque Country, Catalonia and Galicia. (Other communities chose afterwards to identify themselves as nationalities as well). The Basque Country, Catalonia and Navarre have their own police forces (Ertzaintza, Mossos d'Esquadra and the Chartered Police respectively) while the National Police Corps operates in the rest of the autonomous communities. On the other hand, two communities (the Basque Country and Navarre) are "communities of chartered regime", that is, they have full fiscal autonomy, whereas the rest are "communities of common regime", with limited fiscal powers (the majority of their taxes are administered centrally and redistributed among them all for fiscal equalization).

The names of the executive government and the legislature vary between communities. Some institutions are restored historical bodies of government of the previous kingdoms or regional entities within the Spanish crown — like the Generalitat of Catalonia — while others are entirely new creations. In some, both the executive and the legislature, though constituting two separate institutions, are collectively identified with a specific name. A specific denomination may not refer to the same branch of government in all communities; for example, "Junta" may refer to the executive office in some communities, to the legislature in others, or to the collective name of all branches of government in others.

| Autonomous community | Collective name of institutions | Executive | Legislature | Identity | Co-official language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | Board of Andalusia | Council of Government | Parliament of Andalusia | Nationality | |

| Aragon | Government of Aragon | Government | Cortes of Aragon | Nationality | |

| Asturias | Government of the Princedom of Asturias | Council of Government | General Junta | Region[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Balearic Islands | Government of the Balearic Islands | Government | Parliament of the Balearic Islands | Nationality | Catalan |

| Basque Country | Basque Government | Government | Basque Parliament | Nationality | Basque |

| Canary Islands | Government of the Canary Islands | Government | Parliament of Canarias | Nationality | |

| Cantabria | Government of Cantabria | Government | Parliament of Cantabria | Region[lower-alpha 2] | |

| Castile-La Mancha | Regional Government of Castile-La Mancha | Council of Government | Cortes of Castile-La Mancha | Region | |

| Castile and León | Board of Castile and León | Board of Castile and León | Cortes of Castile and León | Region[lower-alpha 3] | |

| Catalonia | Generalitat of Catalonia | Council of Government | Parliament of Catalonia | Nationality | Catalan, Occitan |

| Community of Madrid | Government of the Community of Madrid | Government | Assembly of Madrid | Community[lower-alpha 4] | |

| Extremadura | Board of Extremadura | Board of Extremadura | Assembly of Extremadura | Region | |

| Galicia | Board of Galicia | Board of Galicia | Parliament of Galicia | Nationality | Galician |

| La Rioja | Government of La Rioja | Government | Parliament of La Rioja | Region | |

| Murcia | Government of the Región de Murcia | Council of Government | Regional Assembly of Murcia | Region | |

| Navarre | Government of Navarre | Government | Parliament of Navarre | Regional law community[lower-alpha 5] | Basque |

| Valencian Community | Generalitat Valenciana | Council of Government | Corts Valencianes | Nationality | Catalan[lower-alpha 6] |

The two autonomous cities have more limited competences. The executive is exercised by a president, which is also the major of the city. In the same way, limited legislative power is vested in a local Assembly in which the deputies are also the city councilors.

Local government

The constitution also guarantees certain degree of autonomy to two other "local" entities: the provinces of Spain (subdivisions of the autonomous communities) and the municipalities (subdivisions of the provinces). If the communities are integrated by a single province, then the institutions of government of the community replace those of the province. For the rest of the communities, provincial government is held by Provincial Deputations or Councils. With the creation of the autonomous communities, deputations have lost much of their power, and have a very limited scope of actions, with the exception of the Basque Country, where provinces are known as "historical territories" and their bodies of government retain more faculties. Except in the Basque Country, members of the Provincial Deputations are indirectly elected by citizens according to the results of the municipals elections and all of their members must be councilors of a town or a city in the province. In the Basque Country direct elections do take place.

Spanish municipal administration is highly homogenous; most of the municipalities have the same faculties, such as managing the municipal police, traffic enforcement, urban planning and development, social services, collecting municipal taxes, and ensuring civil defense. In most municipalities, citizens elect the municipal council, which is responsible for electing the mayor, who then appoints a board of governors or councilors from his party or coalition. The only exceptions are municipalities with under 50 inhabitants, which act as an open council, with a directly elected major and an assembly of neighbors. Municipal elections are held every four years on the same date for all municipalities in Spain. Councilors are allotted using the D'Hondt method for proportional representation with the exception of municipalities with under 100 inhabitants where block voting is used instead. The number of councilors is determined by the population of the municipality; the smallest municipalities having 5, and the largest — Madrid — having 57.

Political parties

Spain is a multi-party constitutional parliamentary democracy. According to the constitution, political parties are the expression of political pluralism, contributing to the formation and expression of the will of the people, and are an essential instrument of political participation.[23] Their internal structure and functioning must be democratic. The Law of Political Parties of 1978 provides them with public funding whose quantity is based on the number of seats held in the Cortes Generales and the number of votes received.[11] Since the mid-1980s two parties dominate the national political landscape in Spain: the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (Spanish: Partido Socialista Obrero Español) and the People's Party (Spanish: Partido Popular).

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) is a social democratic centre-left political party. It was founded in 1879 by Pablo Iglesias, at the beginning as a Marxist party for the workers' class, which later evolved towards social-democracy. Outlawed during Franco's dictatorship, it gained recognition during the Spanish transition to democracy period, when it officially renounced Marxism, under the leadership of Felipe González. It played a key role during the transition and the Constituent Assembly that wrote the Spanish current constitution. It governed Spain from 1982 to 1996 under the prime ministership of Felipe González. It governed again from 2004 to 2011 under the prime ministership of José Luis Rodriguez Zapatero.

The People's Party (PP) is a conservative centre-right party that took its current name in 1989, replacing the previous People's Alliance, a more conservative party founded in 1976 by seven former Franco's ministers. In its refoundation it incorporated the Liberal Party and the majority of the Christian democrats. In 2005 it integrated the Democratic and Social Center Party. It governed Spain under the prime ministership of José María Aznar from 1996 to 2004, and again from December 2011, and after much uncertainty caused by the inconclusive results of the 2015 general election and the 2016 election when the People's Party formed a minority government with confidence and supply support from conservative Ciudadanos (Cs) and the Canarian Coalition (CC), which passed due to the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) abstaining. A motion of no confidence in the Spanish government of Mariano Rajoy was held between 31 May and 1 June 2018, registered by the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) after the People's Party(PP) was found to have profited from the illegal kickbacks-for-contracts scheme of the Gürtel case. The motion was successful and resulted in the PSOE leader Pedro Sánchez becoming the new Prime Minister of Spain until his 2019 state budget was rejected requiring him to call a snap election for April 28 of the same year.

The parties or coalitions represented in the Cortes Generales after the 20 December 2015 election are:

- Podemos

- Citizens (Ciudadanos or C's)

- Republican Left of Catalonia (Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya or ERC)

- Democracy and Freedom (Democràcia i Llibertat or DiL)

- Basque Nationalist Party (Euzko Alderdi Jeltzalea, Partido Nacionalista Vasco, Parti National Basque, or PNV)

- Canarian Coalition (Coalición Canaria or CC-PNC)

- Plural Left (Spanish: Izquierda Plural, IP); a coalition of several left-wing parties, among which the largest party is the United Left (Spanish: Izquierda Unida, IU)

- Basque Country Unite (Euskal Herria Bildu or EHB).

Other parties represented in Congress from 2011 to 2015 were:

- Convergence and Union (Catalan: Convergència i Unió, CiU), a coalition of two Catalan nationalist parties; after its dissolution Democratic Convergence of Catalonia (Catalan: Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya, CDC) renamed as Democracy and Freedom (Democràcia i Llibertat or DiL).

- Socialists' Party of Catalonia (Catalan: Partit dels Socialistas de Catalunya, PSC), now integrated in the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE)

- Amaiur, a coalition of Basque nationalist parties

- Union, Progress and Democracy (Spanish: Unión, Progreso y Democracia, UPyD)

- Galician Nationalist Bloc (Galician: Bloque Nacionalista Galego, BNG)

- Commitment Coalition (Catalan: Coalició Compromís),[24] a coalition of Valencian parties, now in a coalition with Podemos.

- Citizen's Forum,

- Yes to the Future (Basque: Geroa Bai).

In addition, the Aragonese Party, United Extremadura, and the Union of Navarrese People participated in the 2011 elections forming regional coalitions with the People's Party.

Electoral process

Suffrage is free and secret to all Spanish citizens of age 18 and older to all elections, and to residents who are citizens of all European Union countries only in local municipal elections and elections to the European Parliament.

Congress of Deputies

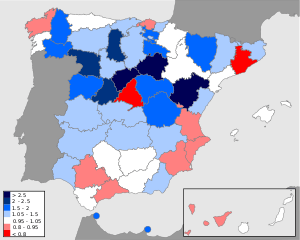

Elections to the Cortes Generales are held every four years or before if the prime minister calls for an early election. Members of the Congress of Deputies are elected through proportional representation with closed party lists where provinces serve as electoral districts; that is, a list of deputies is selected from a province-wide list.[11] Under the current system, sparsely populated provinces are overrepresented because more seats of representatives are allocated to the sparsely populated provinces than they would have if number of seats are allocated strictly according to the population proportion.[11][25]

Not only provinces with small population are over-represented in Spain's election system, the system also tends to favors major political parties.[26] Despite the use of proportional representation voting system, which in general encourages the development of a larger number of small political parties rather than a few larger ones, Spain has effectively a two-party system in which smaller and regional parties tend to be underrepresented.[11][27] This is owing to various reasons:

- Due to the great disparity in population among provinces, even though smaller provinces are overrepresented, the total number of deputies assigned to them is still small and tends to go to one or two major parties, even if other smaller parties managed to obtain more than 3% of the votes - the minimum threshold for representation in the Congress.[27]

- The average district magnitude (the average number of seats per constituency) is one of the lowest in Europe, owing to the large number of constituencies.[28] The low district magnitude tends to increase the number of wasted votes (the votes that could not affect the election results because they have been cast for the small parties which could not pass the effective threshold), and in turn increase the disproportionality (so the number of seats and the portion of votes got by a party becomes less proportional).[29] It is often regarded as the most important factor that limits the number of parties in Spain.[26][30][31] This point is advanced when Baldini and Pappalardo compare it with the case of Netherlands, where the parliament is elected using proportional representation in a single national constituency. There, the parliament is much more fragmented and the number of parties is much higher than in Spain.[30]

- The D'Hondt method (a type of highest average method) is used to allocate the seats, which slightly favors the major parties when compared to Sainte-Laguë method (another type of highest average method) or the normal kinds of largest remainder methods.[32][33] It is suggested that the use of D'Hondt method also contribute to a certain degree, though not as large as the low number of seats per constituency, to the bipolarization of the party system.[26][30]

- The 3% threshold for entering the Congress is ineffective in many provinces, where the number of seats per constituency is so low that the actual threshold to enter the Congress is effectively higher, and thus many parties cannot obtain representation in Congress despite having obtained more than the 3% threshold in the constituency.[26] For example, the actual threshold for the constituencies having 3 seats is 25%, much higher than 3%, making the 3% threshold irrelevant.[27][30] However, in the largest constituencies like Madrid and Barcelona, where the number of seats is much higher, the 3% threshold is still effective to eliminate the smallest parties.[26]

- The size of the Congress (350 members) is relatively small.[25] It is suggested by Lijphart that the small size of parliament may encourage disproportionality and so favor the large parties.[34]

Senate

In the Senate, each province, with the exception of the islands, select four senators using block voting: voters cast ballots for three candidates, and the four senators with the greatest number of votes are selected. The number of senators selected for the islands varies, depending on their size, from 3 to 1 senators. A similar procedure of block voting is used to select the three senators from the three major islands whereas the senators of the smaller islands or group of islands, are elected by plurality. In addition, the legislative assembly of each autonomous community designates one senator, and another for each additional one million inhabitants.

Electoral participation

Electoral participation, which is not compulsory, has traditionally been high, peaking just after democracy was restored in the late 1970s, falling during the 1980s, but trending upwards in the 1990s.[11] Since then, voting abstention rate has been around one-fifth to nearly one-third of the electorate.[11]

Recent historical political developments

The end of the Spanish Civil War put at end to the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939), after which a dictatorial regime was established, headed by general Francisco Franco. In 1947 he decreed, in one of the eight Fundamental Laws of his regime, the Law of Succession of the Head of State, that Spain was a monarchy with a vacant throne, that Franco was the head of State as general and caudillo of Spain, and that he would propose, when he deemed opportune, his successor, who would bear the title of King or Regent of Spain. Even though Juan of Bourbon, the legitimate heir of the monarchy, opposed the law, Franco met him in 1948, when they agreed that his son, Juan Carlos, then 10 years old, would finish his education in Spain — he was then living in Rome — according to the "principles" of the Francoist movement. In 1969, Franco finally designated Juan Carlos as his successor, with the title "Prince of Spain", bypassing his father Juan of Bourbon.

Francisco Franco died on 20 November 1975, and Juan Carlos was crowned King of Spain by the Spanish Cortes, the non-elected Assembly that operated during Franco's regime. Even though Juan Carlos I had sworn allegiance to "National Movement", the sole legal party of the regime, he expressed his support for a transformation of the Spanish political system as soon as he took office. Such an endeavor was not meant to be easy or simple, as the opposition to the regime had to ensure that nobody in their ranks would turn into extremism, and the Army had to resist the temptation to intervene to restore the "Movement".

In 1976 he designated Adolfo Suárez as prime minister — "president of the Government" — with the task of convincing the regime to dismantle itself and to call for elections to a Constituent Assembly. He accomplished both tasks, and the first democratically elected Constituent Cortes since the Second Spanish Republic met in 1977. In 1978 a new democratic constitution was promulgated and approved by referendum. The constitution declared Spain a constitutional parliamentary monarchy with H.M. King Juan Carlos I as Head of State. Spain's transformation from an authoritarian regime to a successful modern democracy was a remarkable achievement, even creating a model emulated by other countries undergoing similar transitions.[35]

Adolfo Suárez headed the prime ministership of Spain from 1977 to 1982, as the leader of the Union of the Democratic Center party. He resigned on 29 January 1981, but on 23 February 1981, day when the Congress of Deputies was to designate a new prime minister, rebel elements among the Civil Guard seized the Cortes Generales in an a failed coup that ended the day after. The great majority of the military forces remained loyal to the King, who used his personal and constitutional authority as commander-in-chief of the Spanish Armed forces, to diffuse the uprising and save the constitution, by addressing the country on television.[11]

In October 1982, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party, led by Felipe González, swept both the Congress of Deputies and Senate, winning an absolute majority in both chambers of the Cortes Generales. González headed the prime ministership of Spain for the next 13 years, during which period Spain joined NATO and the European Community.

_(cropped).jpg)

The government also created new social laws and large scale infrastructural buildings, expanding the educational system and establishing a welfare state. While traditionally affiliated with one of Spain's major trade unions, the General Union of Workers (UGT), in an effort to improve Spain's competitiveness in preparation for admission to the EC as well as for further economic integration with Europe afterwards, the PSOE distanced itself from trade unions.[36] Following a policy of liberalization, González's government closed state corporations under the state holding company, the National Industry Institute (INI), and down-sized the coal, iron and steel industries. The PSOE implemented the single market policies of the Single European Act and the domestic policies consistent with the Maastricht Treaty EMU criteria.[36] The country was massively modernized and economically developed in this period, closing the gap with other European Community members. There was also a significant cultural shift, into a tolerant contemporary open society.

In March 1996, José María Aznar, from the People's Party, obtained a relative majority in Congress. Aznar moved to further liberalize the economy, with a program of complete privatization of state-owned enterprises, labor market reform and other policies designed to increase competition in selected markets. Aznar liberalized the energy sector, national telecommunications and television broadcasting networks.[36] To ensure a successful outcome of such liberalization, the government set up the Competition Defense Court (Spanish: Tribunal de Defensa de la Competencia), an anti-trust regulator body entrusted with restricting monopolistic practices.[36] During Aznar's government Spain qualified for the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union, and adopted the euro, replacing the peseta, in 2002. Spain participated, along with the United States and other NATO allies, in military operations in the former Yugoslavia. Spanish armed forces and police personnel were included in the international peacekeeping forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo. Having obtained an absolute majority in the 2000 elections, Aznar, headed the prime ministership until 2004. Aznar supported transatlantic relations with the United States, and participated on the War on Terrorism and the invasion of Iraq. In 2004, he decided not to run as a candidate for the Popular Party, and proposed Mariano Rajoy, who had been minister under his government, as his successor as leader of the party.

In the aftermath of the terrorist bomb attacks in Madrid, which occurred just three days before the elections, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party won a surprising victory. Its leader, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, headed the prime ministership from 2004 to 2011, winning a second term in 2008. Under a policy of gender equality, his was the first Spanish Government to have the same number of male and female members in the Council of Ministers. During the first four years of his prime ministership the economy continued to expand rapidly, and the government ran budget surpluses. His government brought social liberal changes to Spain, promoting women's rights, changing the abortion law, and legalizing same-sex marriage, and tried to make the State more secular.[37] The economic crisis of 2008 took a heavy toll on Spain's economy, which had been highly dependent on construction since the boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s. When the international financial crisis hit, the construction industry collapsed, along with property values and several banks and cajas (savings banks) were in need of rescuing or consolidation.[37] Economic growth slowed sharply and unemployment soared to over 20%,[37] levels not seen since the late 1990s. In applying counter-cyclical policies during the beginning of the crisis, and the ensuing drop in State revenues, the government financing fell into deficit. During an 18-month period from 2010 to 2011, the government adopted severe austerity measures, cutting spending and laying off workers.[37]

In March 2011, Rodríguez Zapatero made his decision not to lead the Socialist Party in the coming elections, which he called ahead of schedule for 20 November 2011. The People's Party, which presented Mariano Rajoy for the third time as candidate, won a decisive victory,[37] obtaining an absolute majority in the Congress of Deputies. Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba, first deputy prime minister during Rodríguez Zapatero's government and candidate for the Socialist Party in 2011, was elected secretary general of his party in 2012, and became the leader of the opposition in Parliament.

The elections of 20 December 2015 were inconclusive, with the People's Party remaining the largest party in Congress, but unable to form a majority government. The PSOE remained the second largest party, but the Podemos and Ciudadanos parties also obtained substantial representation; coalition negotiations were prolonged[38] but failed to install a new government. This led to a further general election on 26 June 2016, in which the PP increased its number of seats in parliament, while still falling short of an overall majority.[39] Eventually on 29 October, Rajoy was re-appointed as prime minister after the majority of the PSOE members abstained in the parliamentary vote rather than oppose him.[40]

Key political issues

The nationality debate

Spanish political developments since the early twentieth century have been marked by the existence of peripheral nationalisms and the debate of whether Spain can be viewed as a plurinational federation. Spain is a diverse country with different and contrasting polities showing varying economic and social structures, as well as different languages and historical, political and cultural traditions.[41][42] Peripheral nationalist movements have been present mainly in the Basque Country, Catalonia and Galicia, some advocating for a special recognition of their "national identity" within the Spanish nation and others for their right of self-determination or independence.

The Constituent Assembly in 1978 struck a balance between the opposing views of centralism, inherited from Franco's regime, and those who viewed Spain as a "nation of nations". In the second article, the constitution recognizes the Spanish nation as the common and indivisible homeland of all Spaniards, integrated by nationalities and regions. In practice, and as it began to be used in Spanish jurisprudence, the term "nationalities" makes reference to those regions or autonomous communities with a strong historically constituted sense of identity or a recognized historical cultural identity,[43][44] as part of the indivisible Spanish nation. This recognition, and the process of devolution within the "State of Autonomies" has led to the legitimation of the Spanish state among the "nationalities", and many of its citizens feel content within the current status quo.[45] Nonetheless, tensions between peripheral nationalism and centralism continue, with some nationalist parties still advocating for a recognition of the other "nations" of the Spanish Kingdom or for a peaceful process towards self-determination. The 2014 Catalan self-determination referendum resulted in a vote of 80.76% for independence, with a turnout percentage of 37.0%, and it was supported by five political parties.

Terrorism

The Government of Spain has been involved in a long-running campaign against Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA), an armed secessionist organization founded in 1959 in opposition to Franco and dedicated to promoting Basque independence through violent means, though originally violence was not a part of their method. They consider themselves a guerrilla organization but are considered internationally as a terrorist organisation. Although the government of the Basque Country does not condone any kind of violence, their different approaches to the separatist movement are a source of tension between the Central and Basque governments.

Initially ETA targeted primarily Spanish security forces, military personnel and Spanish Government officials. As the security forces and prominent politicians improved their own security, ETA increasingly focused its attacks on the tourist seasons (scaring tourists was seen as a way of putting pressure on the government, given the sector's importance to the economy) and local government officials in the Basque Country. The group carried out numerous bombings against Spanish Government facilities and economic targets, including a car bomb assassination attempt on then-opposition leader Aznar in 1995, in which his armored car was destroyed but he was unhurt. The Spanish Government attributes over 800 deaths to ETA during its campaign of terrorism.

On 17 May 2005, all the parties in the Congress of Deputies, except the PP, passed the Government's motion giving approval to the beginning of peace talks with ETA, without making political concessions and with the requirement that it give up its weapons. PSOE, CiU, ERC, PNV, IU-ICV, CC and the mixed group —BNG, CHA, EA and NB— supported it with a total of 192 votes, while the 147 PP parliamentarians objected. ETA declared a "permanent cease-fire" that came into force on 24 March 2006 and was broken by Barajas T4 International Airport Bombings on 30 December 2006. In the years leading up to the permanent cease-fire, the government had had more success in controlling ETA, due in part to increased security cooperation with French authorities.

Spain has also contended with a Marxist resistance group, commonly known as GRAPO. GRAPO (Revolutionary group of 1 October) is an urban guerrilla group, founded in Vigo, Galicia; that seeks to overthrow the Spanish Government and establish a Marxist–Leninist state. It opposes Spanish participation in NATO and U.S. presence in Spain and has a long history of assassinations, bombings, bank robberies and kidnappings mostly against Spanish interests during the 1970s and 1980s.

In a June 2000 communiqué following the explosions of two small devices in Barcelona, GRAPO claimed responsibility for several attacks throughout Spain during the past year. These attacks included two failed armored car robberies, one in which two security officers died, and four bombings of political party offices during the 1999-2000 election campaign. In 2002, Spanish authorities were successful in hampering the organization's activities through sweeping arrests, including some of the group's leadership. GRAPO is not capable of maintaining the degree of operational capability that they once enjoyed. Most members of the groups are either in jail or abroad.

International organization participation

Spain is a member of AfDh, AsDB, Australia Group, BIS, CCC, CE, CERN, EAPC, EBRD, ECE, ECLAC, EIB, EMU, ESA, EU, FAO, IADB, IAEA, IBRD, ICAO, ICC, ICC, ICFTU, ICRM, IDA, IEA, IFAD, IFC, IFRCS, IHO, ILO, IMF, IMO, Inmarsat, Intelsat, Interpol, IOC, IOM (observer), ISO, ITU, LAIA (observer), NATO, NEA, NSG, OAS (observer), OECD, OPCW, OSCE, PCA, United Nations, UNCTAD, UNESCO, UNHCR, UNIDO, UNMIBH, UNMIK, UNTAET, UNU, UPU, WCL, WEU, WHO, WIPO, WMO, WToO, WTrO, Zangger Committee

References

- Informational notes

- Also identified as a "historical community" in its Statute of Autonomy

- Also identified as a "historical community" in its Statute of Autonomy.

- Also identified as a "historical and cultural community" in its Statute of Autonomy.

- The Community of Madrid was detached from Castile-La Mancha to conform a distinct autonomous community in the nation's interest since its capital, Madrid, is also the capital of the Spanish nation, and seat of the State's institutions of government. It is therefore, not referred to neither as a region nor as a nationality in its Statute of Autonomy.

- Navarra acceded to self-government through the "reintegration" and "improvement" of its medieval regional code of laws whereby it had some autonomy to manage its internal affairs.

- In Valencia, the language is historically and officially known as Valencian.

- Citations

- First article. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Muro & Lago 2020, p. 7.

- Fishman 2020, p. 27.

- solutions, EIU digital. "Democracy Index 2016 - The Economist Intelligence Unit". www.eiu.com. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Article 56. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Abellán Matesanz, Isabel María. "Sinópsis arículo 56 de la Constitución Española (2003, updated 2011)". Cortes Generales. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- Article 61. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Article 62. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Article 63. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Solsten, Eric; Meditz, Sandra W. (1998). "King, Prime Minister, and Council of Ministers". Spain, a country Study. Washington GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- Sir Raymond Carr; et al. "Spain". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Merino Merchán, José Fernando (December 2003). "Sinópsis artículo 62 de la Constitución Española". Cortes Generales. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- Article 57. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Abellán Matesanz, Isabel María. "Sinópsis arículo 57 de la Constitución Española (2003, updated 2011)". Cortes Generales. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- "Spain". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Alba Navarro, Manuel. "Sinópsis artículo 66 de la Constitución Española (December 2003, updated 2011)". Cortes Generales. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Alba Navarro, Manuel. "Sinópsis artículo 69 de la Constitución Española (December 2003, updated 2011)". Cortes Generales. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Article 99. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Article 107. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Article 117. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Article 159. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Article 2. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Article 6. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Valencian is the regional, historical and official name for the Catalan language in the Valencian Community

- Colomer, Josep (2004). Hand Book Of Electoral System Choice. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-4039-0454-6.

- Álvarez-Rivera, Manuel. "Elections to the Spanish Congress of Deputies". Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- González, Yolanda (23 December 2007). "Las verdades y mentiras de la ley electoral". El País. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Baldini, Gianfranco; Pappalardo, Adriano (2011). Elections, Electoral Systems and Volatile Voters. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-230-57448-9.

- Farrell, David (2011). Electoral Systems: A Comparative Introduction (2 ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 74–77. ISBN 978-1-4039-1231-2.

- Baldini, Gianfranco; Pappalardo, Adriano (2011). Elections, Electoral Systems and Volatile Voters. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-0-230-57448-9.

- Norris, Pippa (2004). Electoral Engineering - Voting Rules and Political Behavior. USA: Cambridge University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-521-82977-9.

- Farrell, David (2011). Electoral Systems: A Comparative Introduction (2 ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 67–74. ISBN 978-1-4039-1231-2.

- Baldini, Gianfranco; Adriano Pappalardo (2011). Elections, Electoral Systems and Volatile Voters. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 61–64. ISBN 978-0-230-57448-9.

- Farrell, David (2011). Electoral Systems: A Comparative Introduction (2 ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4039-1231-2.

- Gunther, Richard; Monero, José Ramón (2009). "The Politics of Spain". Cambridge Textbooks in Comparative Politics. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Spain Politics, government, and taxation". Encyclopedia of the Nations. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Minder, Raphael (20 November 2011). "Spanish Voters Deal a Blow to Socialists over the Economy". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Stephen Burgen, "'Worrying and pathetic': anger in Spain over parties' failure to form government", The Guardian, 17 February 2016

- Jones, Sam (27 June 2016). "Spanish elections: Mariano Rajoy struggles to build coalition". The Guardian.

- Jones, Sam (31 October 2016). "Mariano Rajoy sworn in as Spain's PM after deadlock broken". The Guardian.

- Villar, Fernando P. (June 1998). "Nationalism in Spain: Is It a Danger to National Integrity?". Storming Media, Pentagon Reports. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- Shabad, Goldie; Gunther, Richard (July 1982). "Language, Nationalism and Political Conflict in Spain". Comparative Politics. Comparative Politics Vol 14 No. 4. 14 (4): 443–477. doi:10.2307/421632. JSTOR 421632.

- "Nacionalidad". Real Academia Española. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Lewis, Martin W (1 September 2010). "The Nation, Nationalities, and Autonomous Regions in Spain". GeoCurrents. Map-Illustrated Analyses of Current Events and Geographical Issues. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Conversi, Daniele (2002). "The Smooth Transition: Spain's 1978 Constitution and the Nationalities Question" (PDF). National Identities, Vol 4, No. 3. Carfax Publishing, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2008.

- Bibliography

- Fishman, Robert M. (2020). "Spain in comparative perspective". In Muro, Diego; Lago, Ignacio (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Spanish Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-882693-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Muro, Diego; Lago, Ignacio (2020). "Introduction". In Muro, Diego; Lago, Ignacio (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Spanish Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-882693-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Politics of Spain. |