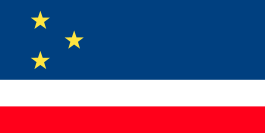

Flag of Gagauzia

The flag of Gagauzia (Gagauz: Gagauz Yerin bayraa) has served as an official symbol of the Gagauz Territorial Unit since 1995, and is recognized as a regional symbol by Moldova. Popularly known as the "Sky Flag", it is a triband of blue-white-red, with a wider blue stripe, charged with three yellow stars arranged in triangular pattern. The overall symbolism is debated, but the stars may represent the three Gagauz municipalities within Moldova. The tricolor is reminiscent of the Russian flag, which is also popular in Gagauzia; the issue has created friction between Gagauz and Moldovan politicians.

| |

| Names | Gagauz Yerin bayraa, Sky Flag |

|---|---|

| Use | State flag |

| Proportion | 1:2 |

| Adopted | October 31, 1995 |

Variant flag of Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia | |

| Use | Civil flag |

Variant flag of Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia | |

| Use | Ethnic flag |

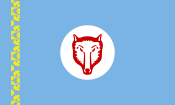

While the emergence of Gagauz nationalism dates back to the 1900s, when it opposed Tsarist autocracy, separate symbols for the Gagauz people and their territory are comparatively new. Several ethnic and semi-official flags were recorded for Gagauz separatists during the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, generally featuring the grey wolf (or bozkurt). The unrecognized Gagauz Republic adopted such symbolism in various forms; the device was featured on its official flag, which reportedly existed in only one copy.

Despite their initial popularity, grey-wolf flags were tainted by controversy, being read as references to Pan-Turkism and the eponymous far-right group. They fell out of use in 2000–2010, but reemerged as popular in the following decade. In 2017, Governor Irina Vlah proposed the introduction of a flag bearing the wolf's head in red as a "historical flag" with official status. If adopted, this resolution would not replace the "Sky Flag".

Symbolism

The current "national flag" of Gagauzia has "a blue field bearing a narrow white and red horizontal stripes on the bottom and three yellow stars on the upper hoist."[1] Reportedly, the three stars stand for "the past, present and future",[2] or, alternatively, for the three constituent municipalities of Gagauzia: Comrat (Komrat), Ceadîr-Lunga (Çadır-Lunga), and Vulcănești (Valkaneş).[3] Writer Ștefan Curoglu was an early proponent of a triband arrangement, which were to attest the ancestry of Gagauz people. In this interpretation, each color represents an ancestral contributor to Gagauz ethnogenesis: the Pechenegs, the Kipchaks, and the Oghuz Turks.[4]

The triband replaced earlier designs with a grey wolf (bozkurt) or wolf's head. These were notably in use under the unrecognized Gagauz Republic of Governor Stepan Topal (1990–1995). According to reports of the time, the imagery recalls "a myth of the Gagauz people's founding", when "a wolf led [the Gagauz] to freedom."[2] Writing in 1990, Curoglu linked the wolf's head with another tradition, that of "nine mourners", or "nine wolves", guarding the Gagauz nation, or with the folkloric depiction of the pole star as a wolf.[4] Other readings describe the bozkurt as a Pan-Turkic symbol, namely as "the legendary grey wolf that led the Turks across the mountains onto the steppes."[5] Researcher Anatol Măcriș claims that the ancient Gagauz flag had "a wolf on a green field", and proposes that it may derive from the Dacian Draco.[6]

History

Origins

The Gagauz trace their origins to the Despotate of Dobruja, being a Turkic or Turkified Christian people which resisted the spread of Islam. Chased out of the Ottoman Empire, they were accepted by the Russian Empire, which settled them in Bessarabia and the Budjak; most of the latter was returned to Moldavia in 1856, together with its Gagauz, but re-annexed by Russia in 1878.[7] Gagauzia first expressed aspirations of becoming an independent nation in the wake of the 1905 Revolution: a small republic, called Gagauz Khalki or "Comrat Republic", survived for two weeks in January 1906.[8] Although cited as a precedent by later nationalists, this polity was mainly concerned with land reform, rather than ethnic self-determination.[9]

A second statehood was established following the February Revolution of 1917, with hopes of joining the Moldavian Democratic Republic (RDM) as an autonomous unit. The community was allocated two seats in the RDM legislature, Sfatul Țării.[10] Invaded by the Ukrainian People's Republic and the Odessa Soviet Republic, the Gagauz polity sought protection from the Kingdom of Romania, and eventually supported the union of Bessarabia with Romania.[11] During the interwar, in Greater Romania, Gagauz nationalism was centered on the localized version of Romanian Orthodoxy, in combination with the tenets of Turkish nationalism, and even Kemalism. The synthesis was effected by the priest and propagandist Mihail Ciachir.[12]

Gagauzia developed into a multicultural region under the early stages of Romanian rule.[13] The Gagauz resisted measures to bring about their Romanianization or expulsion, but were also exposed to Russification during the first and second Soviet occupations. This process was intensified following the consolidation of a Moldavian SSR within the Soviet Union, although some linguistic concessions were made in the 1950s and '60s.[14] The first attested nationalist flags of the Gagauz people emerged during the Perestroika years, before the fall of the Moldavian SSR. The emancipation movement used "a light blue field bearing a centered yellow disk charged with a black wolf's head."[1] This was also reported as a black wolf's head in profile, on a golden circle with outer white ring, all on a field of light blue.[4] Another variant of the flag, which was notably painted as a mural in Comrat, is "blue with white borders and has a white medallion in the middle showing the Bozkurt".[5] This was originally a military flag, designed in 1990 by Petru (Pötr) Vlah. In his version, the wolf's head, colored grey, was shown in profile, facing the mast; the bordure was a sewn pattern.[15]

The ethnic flag had numerous other reported variants. A triangular pennon, of uncertain coloring, had the wolf's head, cabossed, on a plain circle, with no outer ring. This version was reported as in use by Topal's government in August 1990, and flown alongside the Soviet flag during the separatist uprising.[4] During the parallel protests for the establishment of Comrat State University, Gagauz activists allegedly used a light-blue field defaced with a red wolf's head on a white disk, with a yellow motif running vertical near the mast.[16][17]

On August 11, 1990, a Gagauz Republic was formed, seceding from the Moldavian SSR and seeking to unite with the Gagauz in Ukraine. Although the new state of Moldova had lost any control over the region by 1992, the nationalist movement became divided between a minority which pressed for Gagauzia to join the Russian Federation and a majority which looked forward to autonomy within Moldova.[18] As reported by historian Frederick Quinn, by 1993 the Topal government was using a new version of the Gagauz flag, its "only extant copy" displayed in Topal's own office. It showed the full-bodied wolf in black, facing the mast and standing on a mound, all within a golden-and-red circle. This was superimposed over a triband closely resembling the current flag, but with a narrower white stripe, and with the three stars aligned vertically.[19]

Under the "Special Status"

In December 1994, Gagauzia and Moldova agreed on a "Special Status" for the former, which became the first autonomous ethnic enclave to achieve recognition in all of post-communist Eastern Europe.[20] This led to the adoption of a revised flag, in its current form, with the nickname "Sky Flag".[21] It was favored over the wolf symbols, which were resented by moderate Gagauz, in particular those who feel a religious solidarity with the Pontic Greeks; the grey wolf was also seen as associated with the far-right of Pan-Turkism, as embodied by the Idealist Hearths.[22] After 2000, the wolf's head symbol has been quietly taken out of public displays.[23] In 2010 the new flag was taken to the top of Mount Elbrus by Anna Zanet, daughter of the nationalist poet-journalist Todur Zanet.[21][24]

Gagauzia's flag remains central to the disputes between Romanian nationalism and those Gagauz who fear a potential unification with Romania. Also in 2010, Governor Mihail Formuzal announced that he and his cabinet opposed the decree by Moldovan President Mihai Ghimpu, which ordered the flying of state symbols at half-mast on June 28—that is, for the commemoration of Soviet annexation. Formuzal referred in particular to the lowering of the "Sky Flag", which "can only be done by order of the Governor. I will not issue such an order."[25] Instead, June 28 was celebrated in Gagauzia as a "day of liberation from Romanian fascist occupation".[25]

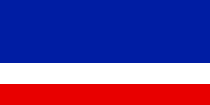

After a unionist rally in May 2012, the Gagauz mayor of Comrat, Nicolai Dudoglo, threatened that his city would only hoist the Gagauz symbols, and remove Moldovan flags.[26] In 2014, in the context of the Ukrainian crisis and pro-Russian unrest on Moldova's borders, there was some concern about similar events unfolding in Moldova. In Moldova's Parliament, Gheorghe Duca moved to ban the Gagauz flag as resembling the flag of Crimea, but his motion was met with opposition from the Party of Communists.[27] Also during that interval, a group of pro-Russian Gagauz in Comrat flew the flag of Russia.[28] Public institutions in Gagauzia still displayed the flag of Europe, honoring Moldova's pro-enlargement policy, but the employees' mood was reported as sour on this issue.[29]

At her swearing-in ceremony the following year, Governor Irina Vlah made a show of kissing the Gagauz flag, and thereafter gave unofficial equal status to the Moldovan and Russian flags.[30] Vlah created additional controversy by wearing a scarf of blue-red-white, colors which are shared by Gagauzia and Russia. Moldovan voices saw this as evidence that Vlah was "set[ting] herself up as a promoter of Russian interests."[31] Russia Day 2016 was openly celebrated in Comrat with Governor Vlah's approval. As Radio Free Europe reports, it saw the Gagauz waiving a "flurry of Russian Federation flags".[32] By March of the following year, the European flag had been reportedly removed from the gubernatorial residence in Comrat.[33]

During August 2017, Governor Vlah announced an initiative to reinstate the "historical flag" of Gagauzia as an official symbol, to be flown on state buildings alongside the "Sky Flag". Speaking at the time, she identified the former as a flag appearing at public rallies in 1990–1994, and argued that the proposal "has been for long discussed in our society."[17] Illustrations and videos published alongside such reports showed a return to the red wolf's head on a white disk, over a field of light blue.[16][17] According to a report on Realitatea TV, Vlah was inspired by a separatist group, Gagauz Halkı, which resumed its activities in March 2017.[16] In September, Ana Sözü newspaper reported that there were political disagreements which made it improbable that the commission for a new flag would ever be functional.[15]

Notes

- Minahan, p. 630

- Quinn, p. 24

- Bulut, p. 62

- "Nové vlajky. Gagauzsko", in Vexilologie. Zpravodaj Vexilologického Klubu při okd Praha, Issue 81, 1991, pp. 1602–1603

- Smith Albion, p. 6

- Măcriș, p. 58

- Kapaló, pp. 47–53, 58–83; Măcriș, pp. 5–74, 96–99, 117–119, 149–195; Minahan, pp. 631–632

- Bulut, p. 63; Kapaló, p. 54; Minahan, p. 632

- Kapaló, p. 54. See also Basciani, pp. 61–62

- Basciani, p. 89

- Minahan, pp. 632–633

- Kapaló, pp. 56–115. See also Bulut, p. 62

- Măcriș, pp. 60–84

- Kapaló, pp. 53–83; Minahan, pp. 633–634. See also Măcriș, pp. 84–85, 87–89, 106–107, 120–141

- "İş komisiyasız da belli! Gagauz Respublikamızın hem Milli Bayraamızın işi bitti!", in Ana Sözü, September 29, 2017, p. 1

- (in Romanian) Drapelul mișcării separatiste din anii '90 din Găgăuzia va fi oficializat. Irina Vlah: Sub acest simbol s-au desfășurat primele mitinguri, Realitatea TV, August 23, 2017

- (in Romanian) Iurii Botnarenco, "Drapelul așa-numitei Republici Găgăuzia va fi oficializat la Comrat", in Adevărul Moldova, August 19, 2017

- Minahan, p. 634. See also Kapaló, pp. 76–78; Smith Albion, pp. 7–10

- Quinn, pp. 24, 160

- Minahan, p. 634–635. See also Măcriș, pp. 85–87, 106–107; Smith Albion, pp. 6–10

- Ülkü Çelik Şavk, "Todur (Fedor) Zanet Gagauzluk ve Gagauzlara Adanmış Bir Hayat", in Tehlikedeki Diller Dergisi, Winter 2013, p. 134

- Kapaló, pp. 80–81

- Kapaló, p. 81

- (in Romanian) Monitor Media, "Ziarul găgăuz Ana Sözü a ajuns pe Elbrus", in Moldova Azi, August 9, 2010

- (in Romanian) "Comrat: 'Ziua eliberării de sub ocupația fasciștilor români'", in Timpul de Dimineață, June 29, 2010

- (in Romanian) Vitalie Călugăreanu, Moldova. Tendințele unioniste de la Chișinău au agitat Rusia, Deutsche Welle, May 14, 2012

- (in Romanian) "Deputații vor discuta mâine situația Ucrainei în spatele ușilor închise", in Timpul de Dimineață, March 20, 2014

- Paul Goble, Commentaries: A Russian Flag Over Gagauzia, Jamestown Foundation, April 4, 2014

- (in French) Victoria Puiu, "Moldavie. Les Gagaouzes se sentent trop éloignés de la culture européenne", in Courrier International, May 20, 2014

- Kit Gillet, A Tiny Region in Moldova Holds the Key to Understanding Eastern Ukraine's Future, Business Insider, May 25, 2015

- Igor Botan, Real and Imagined Dangers in the Elections in Gagauzia, E-democracy.md (Association for Participatory Democracy ADEPT), March 16, 2015

- (in Romanian) Tatiana Ețco, Cum a fost sărbătorită Ziua Rusiei la Comrat (mai mult) și la Chișinău (mai puțin), Radio Free Europe, June 13, 2016

- (in Romanian) Svetlana Corobceanu, "O zi 'fără politic' în Găgăuzia", in Jurnal de Chișinău, March 17, 2017

References

- Alberto Basciani, La difficile unione. La Bessarabia e la Grande Romania, 1918–1940. Rome: Aracne Editore, 2007. ISBN 978-88-548-1248-2

- Remzi Bulut, "The Economic and Political Structure of Gagauzian Turks", in Journal of Institute of Social Sciences (Mehmet Akif Ersoy University), Vol. 3, Issue 6, Autumn 2016, pp. 60–71.

- James Alexander Kapaló, Text, Context and Performance: Gagauz Folk Religion in Discourse and Practice. Leiden & Boston: Brill Publishers, 2011. ISBN 978-90-04-19799-2

- Anatol Măcriș, Găgăuzii. Bucharest: Editura Paco, 2008.

- James Minahan, Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations. Ethnic and National Groups around the World, Volume II D–K. Westport & London: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002. ISBN 0-313-32110-8

- Frederick Quinn, Democracy at Dawn: Notes from Poland and Points East. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-89096-786-5

- Adam Smith Albion, Travels in Romania, Moldova and Gagauzia, Institute of Current World Affairs Letters, ASA-7 1995, Europe/Russia (May 10, 1995).