Foot binding

Foot binding was the Chinese custom of applying tight wrappings to the feet of young girls to modify their shape and size. The practice possibly originated among upper class court dancers during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period in 10th-century China, then gradually became popular among the elite during the Song dynasty. Foot binding eventually spread to most social classes by the Qing dynasty and the practice finally came to an end in the early 20th century. Bound feet were at one time considered a status symbol as well as a mark of beauty. Yet foot binding was a painful practice and significantly limited the mobility of women, resulting in lifelong disabilities for most of its subjects. Feet altered by binding were called lotus feet.

| Foot binding | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A Chinese woman showing her foot, image by Lai Afong, c. 1870s | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 纏足 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 缠足 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative (Min) Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 縛跤 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 缚跤 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Foot binding was practiced in different forms, and the more severe form of binding may have been developed in the 16th century. It has been estimated that by the 19th century, 40–50% of all Chinese women may have had bound feet, and up to almost 100% among upper-class Chinese women.[1] The prevalence and practice of foot binding however varied in different parts of the country.

There had been attempts to end the practice during the Qing dynasty; Manchu Kangxi Emperor tried to ban foot binding in 1664 but failed.[2] In the later part of the 19th century, Chinese reformers challenged the practice but it was not until the early 20th century that foot binding began to die out as a result of anti-foot-binding campaigns. By 2007, there were only a few surviving elderly Chinese women known to have bound feet.[1]

History

Origin

There are a number of stories about the origin of foot binding before its establishment during the Song dynasty. One of these involves the story of a favourite consort of the Southern Qi emperor Xiao Baojuan, Pan Yunu (died 501 AD), who had delicate feet and danced barefoot on a floor decorated with golden lotus flower design. The emperor expressed admiration and said that "lotus springs from her every step!" (步步生蓮), a reference to the Buddhist legend of Padmavati under whose feet lotus springs forth. This story may have given rise to the terms "golden lotus" or "lotus feet" used to describe bound feet; there is, however, no evidence that Consort Pan ever bound her feet.[3]

The general view is that the practice is likely to have originated in the time of the 10th-century Emperor Li Yu of the Southern Tang, just before the Song dynasty.[2] Li Yu created a six-foot tall golden lotus decorated with precious stones and pearls, and asked his concubine Yao Niang (窅娘) to bind her feet in white silk into the shape of the crescent moon, and perform a ballet-like dance on the points of her feet on the lotus.[2] Yao Niang's dance was said to be so graceful that others sought to imitate her.[4] The binding of feet was then replicated by other upper-class women and the practice spread.[5]

Some of the earliest possible references to foot binding appear around 1100, when a couple of poems seemed to allude to the practice.[6][7][8][9] Soon after 1148,[9] in the earliest extant discourse on the practice of foot binding, scholar Zhang Bangji wrote that a bound foot should be arch shaped and small.[10][11] He observed that "women's footbinding began in recent times; it was not mentioned in any books from previous eras."[9] In the 13th century, scholar Che Ruoshui wrote the first known criticism of the practice: "Little girls not yet four or five years old, who have done nothing wrong, nevertheless are made to suffer unlimited pain to bind [their feet] small. I do not know what use this is."[9][12][13]

The earliest archaeological evidence for foot binding dates to the tombs of Huang Sheng, who died in 1243 at the age of 17, and Madame Zhou, who died in 1274. Each had her feet bound with 6-foot-long gauze strips. Zhou's skeleton was well preserved and showed that her feet fit the narrow, pointed slippers that were buried with her.[9] The style of bound feet found in Song dynasty tombs, where the big toe was bent upward, appears to be different from the norm of later eras, and the excessive smallness of the feet, the "three-inch golden lotus", may be a later development in the 16th century.[14][15]

Later eras

At the end of the Song dynasty, men would drink from a special shoe whose heel contained a small cup. During the Yuan dynasty, some would also drink directly from the shoe itself. This practice was called "toast to the golden lotus" and lasted until the late Qing dynasty.[16]

The first European to mention footbinding was the Italian missionary Odoric of Pordenone in the 14th century during the Yuan dynasty.[17] However, no other foreign visitors to Yuan China mentioned the practice, including Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo (who nevertheless noted the dainty walk of Chinese women who took very small steps), perhaps an indication that it was not a widespread or extreme practice at that time.[18] The practice however was encouraged by the Mongol rulers on their Chinese subjects.[5] The practice became increasingly common among the gentry families, later spreading to the general population, as commoners and theatre actors alike adopted footbinding. By the Ming period, the practice was no longer the preserve of the gentry, but it was considered a status symbol.[19][20][21] As foot binding restricted female movement, one side effect of its rising popularity was the corresponding decline of the art of dance in China in women, and it became increasingly rare to hear about beauties and courtesans who were also great dancers after the Song era.[22][23]

The Manchus issued a number of edicts to ban the practice, first in 1636 when the Manchu leader Hong Taiji declared the founding of the new Qing dynasty, then in 1638, and another in 1664 by the Kangxi Emperor.[19] However, few Han Chinese complied with the edicts and Kangxi eventually abandoned the effort in 1668. By the 19th century, it was estimated that 40–50% of Chinese women had bound feet, and among upper class Han Chinese women, the figure was almost 100%.[1] Bound feet became a mark of beauty and were also a prerequisite for finding a husband. They also became an avenue for poorer women to marry into money in some areas; for example, in late 19th century Guangdong, it was customary to bind the feet of the eldest daughter of a lower-class family who was intended to be brought up as a lady. Her younger sisters would grow up to be bond-servants or domestic slaves and be able to work in the fields, but the eldest daughter would be assumed to never have the need to work. Women, their families and their husbands took great pride in tiny feet, with the ideal length, called the "Golden Lotus", being about three Chinese inches long (around 4 inches or 10 centimetres in Western measurement).[24][25] This pride was reflected in the elegantly embroidered silk slippers and wrappings girls and women wore to cover their feet.

Some women with bound feet might not have been able to walk without the support of their shoes and thus would have been severely limited in their mobility.[26] However, many women with bound feet were still able to walk and work in the fields, albeit with greater limitations than their non-bound counterparts. In the 19th and early 20th century, dancers with bound feet were popular, as were circus performers who stood on prancing or running horses. Women with bound feet in one village in Yunnan Province even formed a regional dance troupe to perform for tourists in the late 20th century, though age has since forced the group to retire.[27] In other areas, women in their 70s and 80s could be found providing limited assistance to the workers in the rice fields well into the 21st century.[1]

Demise

Opposition to foot binding had been raised by some Chinese writers in the 18th century. In the mid-19th century, many of the rebel leaders of the Taiping Rebellion were of Hakka background whose women did not bind their feet, and foot binding was outlawed.[28][29] The rebellion however failed, and Christian missionaries, who had provided education for girls and actively discouraged what they considered a barbaric practice, then played a part in changing elite opinion on footbinding through education, pamphleteering, and lobbying of the Qing court.[30][31] The earliest-known Western anti-foot binding society, Jie Chan Zu Hui (截纏足会), was formed in Xiamen in 1874 by 60-70 women in meeting presided over by a missionary John MacGowan.[32] In 1895, Christian women in Shanghai led by Alicia Little formed the Natural Foot (tianzu, literally Heavenly Foot) Society.[32][33] It was also championed by the Woman's Christian Temperance Movement founded in 1883 and advocated by missionaries including Timothy Richard, who thought that Christianity could promote equality between the sexes.[34]

Reform-minded Chinese intellectuals began to consider footbinding to be an aspect of their culture that needed to be eliminated.[35] In 1883, Kang Youwei founded the Anti-Footbinding Society near Canton to combat the practice, and anti-footbinding societies sprang up across the country, with membership for the movement claimed to reach 300,000.[36] The anti-footbinding movement however stressed pragmatic and patriotic reasons rather than feminist ones, arguing that abolition of footbinding would lead to better health and more efficient labour.[31] Reformers such as Liang Qichao, influenced by Social Darwinism, also argued that it weakened the nation, since enfeebled women supposedly produced weak sons.[37] At the turn of the 20th century, early feminists, such as Qiu Jin, called for the end of foot-binding.[38][39] Many members of anti-footbinding groups pledged to not bind their daughters' feet nor to allow their sons to marry women with bound feet.[32][40] In 1902, the Empress Dowager Cixi issued an anti-foot binding edict, but it was soon rescinded.[41]

In 1912, the new Republic of China government banned foot binding (though not actively implemented),[42] and leading intellectuals of the May Fourth Movement saw footbinding as a major symbol of China's backwardness.[43] Local warlords such as Yan Xishan in Shanxi engaged in their own sustained campaign against footbinding with feet inspectors and fines for those who continued with the practice,[42] while regional governments of the later Nanjing regime also enforced the ban.[30] The campaign against footbinding was very successful in some regions; in one province, a 1929 survey showed that whereas only 2.3% of girls born before 1910 had unbound feet, 95% of those born after were not bound.[44] In a region south of Beijing, Dingxian, where over 99% of women were once bound, no new cases were found among those born after 1919.[45][46] In Taiwan, the practice was also discouraged by the ruling Japanese from the beginning of Japanese rule, and from 1911 to 1915 it was gradually made illegal.[47] The practice however lingered on in some regions in China; in 1928, a census in rural Shanxi found that 18% of women had bound feet,[27] while in some remote rural areas such as Yunnan Province it continued to be practiced until the 1950s.[48][49] In most parts of China, however, the practice had virtually disappeared by 1949.[44] The practice was also stigmatized in Communist China, and the last vestiges of footbinding were stamped out, with the last new case of footbinding reported in 1957.[50][51] By the 21st century, only a few elderly women in China still had bound feet.[52][53] In 1999, the last shoe factory making lotus shoes, the Zhiqiang Shoe Factory in Harbin, closed.[54]

Practice

Variations and prevalence

Foot binding was practiced in various forms and its prevalence varied in different regions. A less severe form in Sichuan, called "cucumber foot" (huanggua jiao) due to its slender shape, folded the four toes under but did not distort the heel and taper the ankle.[27][55] Some working women in Jiangsu made a pretense of binding while keeping their feet natural.[30] Not all women were always bound—some women once bound remained bound all through their lives, but some were only briefly bound, and some were bound only until their marriage.[56] Footbinding was most common among women whose work involved domestic crafts and those in urban areas;[30] it was also more common in northern China where it was widely practiced by women of all social classes, but less so in parts of southern China such as Guangdong and Guangxi where it was largely a practice of women in the provincial capitals or among the gentry.[57][58] It is thought that the necessity for women labour in the fields due to a longer crop-growing season in the South and the impracticability of bound feet working in wet rice fields limited the spread of the practice in the countryside of the South.[59]

Manchu women, as well as Mongol and Chinese women in the Eight Banners, did not bind their feet, and the most a Manchu woman might do was to wrap the feet tightly to give them a slender appearance.[60] The Manchus, wanting to emulate the particular gait that bound feet necessitated, adapted their own form of platform shoes to cause them to walk in a similar swaying manner. These "flower bowl" (花盆鞋) or "horse-hoof" shoes (馬蹄鞋) have a platform generally made of wood two to six inches in height and fitted to the middle of the sole, or they have a small central tapered pedestal. Many Han Chinese in the Inner City of Beijing also did not bind their feet, and it was reported in the mid-1800s that around 50-60% of non-banner women had unbound feet. Bound feet nevertheless became a significant differentiating marker between Han women and Manchu or other banner women.[60]

The Hakka people however were unusual among Han Chinese in not practicing foot binding at all.[61] Most non-Han Chinese people, such as the Manchus, Mongols and Tibetans, did not bind their feet; however, some non-Han ethnic groups did. Foot binding was practiced by the Hui Muslims in Gansu Province,[62] the Dungan Muslims, descendants of Hui from northwestern China who fled to central Asia, were also seen practicing foot binding up to 1948.[63] In southern China, in Guangzhou, 19th century Scottish scholar James Legge noted a mosque that had a placard denouncing foot binding, saying Islam did not allow it since it constituted violating the creation of God.[64]

Process

The process was started before the arch of the foot had a chance to develop fully, usually between the ages of 4 and 9. Binding usually started during the winter months since the feet were more likely to be numb, and therefore the pain would not be as extreme.[65]

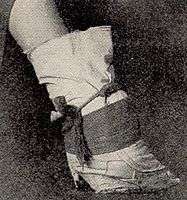

First, each foot would be soaked in a warm mixture of herbs and animal blood; this was intended to soften the foot and aid the binding. Then, the toenails were cut back as far as possible to prevent in-growth and subsequent infections, since the toes were to be pressed tightly into the sole of the foot. Cotton bandages, 3 m long and 5 cm wide (10 ft by 2 in), were prepared by soaking them in the blood and herb mixture. To enable the size of the feet to be reduced, the toes on each foot were curled under, then pressed with great force downward and squeezed into the sole of the foot until the toes broke.

The broken toes were held tightly against the sole of the foot while the foot was then drawn down straight with the leg and the arch of the foot was forcibly broken. The bandages were repeatedly wound in a figure-eight movement, starting at the inside of the foot at the instep, then carried over the toes, under the foot, and around the heel, the freshly broken toes being pressed tightly into the sole of the foot. At each pass around the foot, the binding cloth was tightened, pulling the ball of the foot and the heel together, causing the broken foot to fold at the arch, and pressing the toes underneath the sole. The binding was pulled so tightly that the girl could not move her toes at all and the ends of the binding cloth were then sewn so that the girl could not loosen it.

.jpg)

The girl's broken feet required a great deal of care and attention, and they would be unbound regularly. Each time the feet were unbound, they were washed, the toes carefully checked for injury, and the nails carefully and meticulously trimmed. When unbound, the broken feet were also kneaded to soften them and the soles of the girl's feet were often beaten to make the joints and broken bones more flexible. The feet were also soaked in a concoction that caused any necrotic flesh to fall off.[35]

Immediately after this procedure, the girl's broken toes were folded back under and the feet were rebound. The bindings were pulled even tighter each time the girl's feet were rebound. This unbinding and rebinding ritual was repeated as often as possible (for the rich at least once daily, for poor peasants two or three times a week), with fresh bindings. It was generally an elder female member of the girl's family or a professional foot binder who carried out the initial breaking and ongoing binding of the feet. It was considered preferable to have someone other than the mother do it, as she might have been sympathetic to her daughter's pain and less willing to keep the bindings tight.[65]

For most the bound feet eventually became numb. However, once a foot had been crushed and bound, attempting to reverse the process by unbinding was painful,[66] and the shape could not be reversed without a woman undergoing the same pain all over again.

Health issues

The most common problem with bound feet was infection. Despite the amount of care taken in regularly trimming the toenails, they would often in-grow, becoming infected and causing injuries to the toes. Sometimes, for this reason, the girl's toenails would be peeled back and removed altogether. The tightness of the binding meant that the circulation in the feet was faulty, and the circulation to the toes was almost cut off, so any injuries to the toes were unlikely to heal and were likely to gradually worsen and lead to infected toes and rotting flesh. The necrosis of the flesh would also initially give off a foul odor, and later the smell may come from various microorganisms that colonized the folds.[67]

If the infection in the feet and toes entered the bones, it could cause them to soften, which could result in toes dropping off; however, this was seen as a benefit because the feet could then be bound even more tightly. Girls whose toes were more fleshy would sometimes have shards of glass or pieces of broken tiles inserted within the binding next to her feet and between her toes to cause injury and introduce infection deliberately. Disease inevitably followed infection, meaning that death from septic shock could result from foot-binding, and a surviving girl was more at risk for medical problems as she grew older. It is thought that as many as 10% of girls may have died from gangrene and other infections due to footbinding.[68]

At the beginning of the binding, many of the foot bones would remain broken, often for years. However, as the girl grew older, the bones would begin to heal. Even after the foot bones had healed, they were prone to re-breaking repeatedly, especially when the girl was in her teenage years and her feet were still soft. Bones in the girls' feet would often be deliberately broken again in order to further change the size or shape of the feet. This was especially the case with the toes, as small toes were especially desirable.[69] Older women were more likely to break hips and other bones in falls, since they could not balance securely on their feet, and were less able to rise to their feet from a sitting position.[70] Other issues that might arise from foot binding included paralysis and muscular atrophy.[66]

Views and interpretations

There are many interpretations to the practice of footbinding. The interpretive models used include fashion (the Chinese customs may be compared to examples of Western women's fashion such as corsetry); seclusion (sometimes evaluated as morally superior to the gender mingling in the West); perversion (the practice imposed by men with sexual perversions), inexplicable deformation, child abuse, and extreme cultural traditionalism. In the late 20th century some feminists introduced positive overtones, arguing that it gave women a sense of mastery over their bodies, and pride in their beauty.[71]

Beauty and erotic appeal

Before footbinding was practiced in China, admiration for small feet already existed as demonstrated by the Tang dynasty tale of Ye Xian written around 850 by Duan Chengshi. This tale of a girl who lost her shoe and then married a king who sought the owner of the shoe as only her foot was small enough to fit the shoe contains elements of the European story of Cinderella, and is thought to be one of its antecedents.[72][73] For many, the bound feet were an enhancement to a woman's beauty and made her movement more dainty,[74] and a woman with perfect lotus feet was likely to make a more prestigious marriage. The desirability varies with the size of the feet – the perfect bound feet and the most desirable (called "golden lotuses") would be around 3 Chinese inches (around 4 inches (10 cm) in Western measurement) or smaller, while those larger may be called "silver lotuses" (4 Chinese inches) or "iron lotuses" (5 Chinese inches or larger and the least desirable for marriage).[75] The belief that footbinding made women more desirable to men is widely used as an explanation for the spread and persistence of footbinding.[76]

Some also considered bound feet to be intensely erotic, and Qing Dynasty sex manuals listed 48 different ways of playing with women's bound feet. Some men preferred never to see a woman's bound feet, so they were always concealed within tiny "lotus shoes" and wrappings. According to Robert van Gulik, the bound feet were also considered the most intimate part of a woman's body; in erotic art of the Qing to Song periods where the genitalia may be shown, the bound feet were never depicted uncovered.[77] Howard Levy however suggests that the barely revealed bound foot may also only function as an initial tease.[76]

An erotic effect of the bound feet was the lotus gait, the tiny steps and swaying walk of a woman whose feet had been bound. Women with such deformed feet avoided placing weight on the front of the foot and tended to walk predominantly on their heels.[65] Walking on bound feet necessitated bending the knees slightly and swaying to maintain proper movement and balance, a dainty walk that was also considered to be erotically attractive to some men.[78] Some men found the smell of the bound feet attractive, and some also apparently believed that bound feet would cause layers of folds to develop in the vagina, and that the thighs would become sensuously heavier and the vagina tighter.[79] The psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud considered footbinding to be a "perversion that corresponds to foot fetishism".[80]

Role of Confucianism

A common argument is that the revival of Confucianism as Neo-Confucianism during the Song dynasty resulted in the decline of the status of women, and that in addition to promoting the seclusion of women and the cult of widow chastity, it also contributed to the development of footbinding.[81] According to Robert van Gulik, the prominent Song Confucian scholar Zhu Xi stressed the inferiority of women as well as the need to keep men and women strictly separate.[82] It was claimed by Lin Yutang among others, probably based on an oral tradition, that Zhu Xi also promoted footbinding in Fujian as a way of encouraging chastity among women, that by restricting their movement it would help keep men and women separate.[81] However, historian Patricia Ebrey suggests that this story might be fictitious.[83]

Some Confucian moralists in fact disapproved of the erotic associations of footbinding, and unbound women were also praised.[84] The Neo-Confucian Cheng Yi was said to be against footbinding and his family and descendants did not bind their feet.[85][86] Modern Confucian scholars such as Tu Weiming also dispute any causal link between neo-Confucianism and footbinding.[87] It has been noted that Confucian doctrine in fact prohibits mutilation of the body as people should not "injure even the hair and skin of the body received from mother and father". It is however argued that such injunction applies less to women, rather it is meant to emphasize the sacred link between sons and their parents. Furthermore, it is argued that Confucianism institutionalized the family system in which women are called upon to sacrifice themselves for the good of the family, a system that fostered such practice.[88]

Historian Dorothy Ko proposed that footbinding may be an expression of the Confucian ideals of civility and culture in the form of correct attire or bodily adornment, and that footbinding was seen as a necessary part of being feminine as well as being civilized. Footbinding was often classified in Chinese encyclopedia as clothing or a form of bodily embellishment rather than mutilation; one from 1591 for example placed footbinding in a section on "Female Adornments" that included hairdos, powders, and ear-piercings. According to Ko, the perception of footbinding as a civilised practice may be evinced from a Ming dynasty account that mentioned a proposal to "entice [the barbarians] to civilize their customs" by encouraging footbinding among their womenfolk.[89] The practice was also carried out only by women on girls, and it served to emphasize the distinction between male and female, an emphasis that began from an early age.[90][91] Anthropologist Fred Blake argued that the practice of footbinding was a form of discipline undertaken by women themselves, and perpetuated by women on their daughters, so as to inform their daughters of their role and position in society, and to support and participate in the neo-Confucian way of being civilized.[88]

Feminist perspective

| Part of a series on |

| Violence against women |

|---|

| Issues |

| Killing |

| Sexual assault and rape |

| International legal framework |

| Related topics |

|

Foot binding is often seen by feminists as an oppressive practice against women who were victims of a sexist culture.[92][93] It is also widely seen as a form of violence against women.[94][95][96] Bound feet rendered women dependent on their families, particularly their men, as they became largely restricted to their homes.[97] Thus, the practice ensured that women were much more reliant on their husbands.[98] The early Chinese feminist Qiu Jin, who underwent the painful process of unbinding her own bound feet, attacked footbinding and other traditional practices. She argued that women, by retaining their small bound feet, made themselves subservient as it would mean women imprisoning themselves indoors. She believed that women should emancipate themselves from oppression, that girls can ensure their independence through education, and that they should develop new mental and physical qualities fitting for the new era.[99][39] The ending of the practice is seen as a significant event in the process of female emancipation in China.[100]

In the late 20th century some feminists introduced positive overtones, arguing that it gave women a sense of mastery over their bodies, and pride in their beauty.[101] Historian Dorothy Ko has argued that these feminists have mistakenly imposed late 20th-century middle-class Western ideals of individualism and agency on a highly traditional culture. For example, they assume that the practice represented a woman's individual freedom to enjoy sexuality, despite lack of evidence.[102]

Other interpretations

Some scholars such as Laurel Bossen and Hill Gates reject the notion that bound feet in China were considered more beautiful, or that it was a means of male control over women, a sign of class status, or a chance for women to marry well (in general, bound women did not improve their class position by marriage). They argued that foot binding was an instrumental means to reserve women to handwork, and can be seen as a way by mothers to tie their daughters down, train them in handwork and keep them close at hand, with the practice dying out as industrial textile processes were introduced.[103][104]

It has been argued that while the practice started out as a fashion, it persisted because it became an expression of Han identity after the Mongols invaded China in 1279, and later the Manchus' conquest in 1644, as it was then practiced only by Han women.[90] During the Qing dynasty, attempts were made by the Manchus to ban the practice but failed, and it has been argued the attempts at banning may have in fact led to a spread of the practice among Han Chinese in the 17th and 18th centuries.[105]

In literature, film and television

The bound foot has played a prominent part in many media works, both Chinese and non-Chinese, modern and traditional.[106] These depictions are sometimes based on observation or research and sometimes on rumors or supposition. Sometimes, as in the case of Pearl Buck's The Good Earth (1931), the accounts are relatively neutral or empirical, implying a respect for Chinese culture (note however that Buck's previous novel, "East Wind: West Wind", extensively explores the unbinding of a woman's feet, experienced as frightening and painful yet finally empowering, as part of her transition into a new, more modern and more individualistic persona under her doctor husband's tender tutelage). Sometimes the accounts seem intended to rouse like-minded Chinese and foreign opinion to abolish the custom, and sometimes the accounts imply condescension or contempt for China.[107]

- Quoted in the Jin Ping Mei, ..."displaying her exquisite feet, three inches long and no wider than a thumb, very pointed and with high insteps."[108]

- Flowers in the Mirror (1837) by Ju-Chen Li includes chapters set in the "Country of Women", where men bear children and have bound feet.[109]

- The Three-Inch Golden Lotus (1994) by Feng Jicai[110] presents a satirical picture of the movement to abolish the practice, which is seen as part of Chinese culture.

- In the film The Inn of the Sixth Happiness (1958), Ingrid Bergman portrays British missionary to China Gladys Aylward, who is assigned as a foreigner the task by a local Mandarin to unbind the feet of young women, an unpopular order that the civil government had failed to fulfill. Later, the children are able to escape troops by walking miles to safety.

- Ruthanne Lum McCunn wrote a biographical novel, Thousand Pieces of Gold (1981, adapted into a 1991 film), about Polly Bemis, a Chinese American pioneer woman. It describes her feet being bound, and later unbound, when she needed to help her family with farm labour.

- Emily Prager's short story "A Visit from the Footbinder", from her collection of short stories of the same name (1982), describes the last few hours of a young Chinese girl's childhood before the professional footbinder arrives to initiate her into the adult woman's life of beauty and pain.

- Lisa Loomer's play The Waiting Room (1994) deals with themes of body modification. One of the three main characters is an 18th-century Chinese woman who arrives in a modern hospital waiting room seeking medical help for complications resulting from her bound feet.

- Lensey Namioka's novel Ties that Bind, Ties that Break (1999) follows a girl named Ailin in China who refuses to have her feet bound, which comes to affect her future.[111]

- Lisa See's novel Snow Flower and the Secret Fan (2005) is about two Chinese girls who are destined to be friends. The novel is based upon the sacrifices women make to be married and includes the two girls being forced into getting their feet bound. The book was adapted into a 2011 film directed by Wayne Wang.

- Feng Shui and sequel Feng Shui 2 features a ghost of a foot-bound woman inhabits a bagua and cursed those who holds the item.

See also

- Artificial cranial deformation

- Attraction to disability

- Body modification

- Corset

- Cosmetic surgery

- Foot Emancipation Society

- Foot fetishism

- High-heeled footwear

- Signalling theory

- Women in ancient and imperial China

References

- Lim, Louisa (19 March 2007). "Painful Memories for China's Footbinding Survivors". Morning Edition. National Public Radio.

- "Chinese Foot Binding". BBC.

- Dorothy Ko (2002). Every Step a Lotus: Shoes for Bound Feet. University of California Press. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-0-520-23284-6.

- Dorothy Ko (2002). Every Step a Lotus: Shoes for Bound Feet. University of California Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-520-23284-6.

- Victoria Pitts-Taylor, ed. (2008). Cultural Encyclopedia of the Body. Greenwood. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-313-34145-8.

- "Han Chinese Footbinding". Textile Research Centre.

- Xu Ji 徐積 《詠蔡家婦》: 「但知勒四支,不知裹两足。」(translation: "knowing about arranging the four limbs, but not about binding her two feet); Su Shi 蘇軾 《菩薩蠻》:「塗香莫惜蓮承步,長愁羅襪凌波去;只見舞回風,都無行處踪。偷穿宮樣穩,並立雙趺困,纖妙說應難,須從掌上看。」

- Patricia Buckley Ebrey (1 December 1993). The Inner Quarters: Marriage and the Lives of Chinese Women in the Sung Period. University of California Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 9780520913486.

- Morris, Ian (2011). Why the West Rules - For Now: The Patterns of History, and What They Reveal About the Future. McClelland & Stewart. p. 424. ISBN 978-1-55199-581-6.

- Dorothy Ko (2008). Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding. University of California Press. pp. 111–115. ISBN 978-0-520-25390-2.

- "墨庄漫录-宋-张邦基 8-卷八".

- Valerie Steele; John S. Major (2000). China Chic: East Meets West. Yale University Press. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-0-300-07931-9.

- 车若水. "脚气集". Original text: 妇人纒脚不知起于何时,小儿未四五岁,无罪无辜而使之受无限之苦,纒得小来不知何用。

- Dorothy Ko (2008). Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding. University of California Press. pp. 187–191. ISBN 978-0-520-25390-2.

- Dorothy Ko (2002). Every Step a Lotus: Shoes for Bound Feet. University of California Press. pp. 21–24. ISBN 978-0-520-25390-2.

- Marie-Josèphe Bossan (2004). The Art of the Shoe. Parkstone Press Ltd. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-85995-803-2.

- Ebrey, Patricia (2003-09-02). Women and the Family in Chinese History. Routledge. p. 196. ISBN 9781134442935.

- Haw, Stephen G. (2006-11-22). Marco Polo's China: A Venetian in the Realm of Khubilai Khan. Routledge. pp. 55–56. ISBN 9781134275427.

- Li-Hsiang Lisa Rosenlee (1 February 2012). Confucianism and Women: A Philosophical Interpretation. SUNY Press. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-0-7914-8179-0.

- Valerie Steele; John S. Major (2000). China Chic: East Meets West. Yale University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-300-07931-9.

- Ping Wang (2000). Aching for Beauty: Footbinding in China. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-0-8166-3605-1.

- Anders Hansson (1996). Chinese Outcasts: Discrimination and Emancipation in Late Imperial China. Brill. p. 46. ISBN 978-9004105966.

- Robert Hans van Gulik (1961). Sexual life in ancient China: A Preliminary Survey of Chinese Sex and Society from ca. 1500 B.C. Till 1644 A.D. Brill. p. 222. ISBN 9004039171.

- Hill Gates (2014). Footbinding and Women's Labor in Sichuan. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-415-52592-3.

- Manning, Mary Ellen (10 May 2007). "China's "Golden Lotus Feet" - Foot-binding Practice". Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Bossen, Laurel (2004). "Film Review — Footbinding: Search for the Three Inch Golden Lotus". Anthropologica. 48 (2): 301–303.

- Simon Montlake (November 13, 2009). "Bound by History: The Last of China's 'Lotus-Feet' Ladies". Wall Street Journal.

- Vincent Yu-Chung Shih; Yu-chung Shi (1968). The Taiping Ideology: Its Sources, Interpretations, and Influences. University of Washington Press. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-0-295-73957-1.

- Olivia Cox-Fill (1996). For Our Daughters: How Outstanding Women Worldwide Have Balanced Home and Career. Praeger Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-275-95199-3.

- C Fred Blake (2008). Bonnie G. Smith (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. OUP USA. pp. 327–329. ISBN 978-0-19-514890-9.

- Mary I. Edwards (1986). The Cross-cultural Study of Women: A Comprehensive Guide. Feminist Press at The City University of New York. pp. 255–256. ISBN 978-0-935312-02-7.

- Whitefield, Brent (2008). "The Tian Zu Hui (Natural Foot Society): Christian Women in China and the Fight against Footbinding" (PDF). Southeast Review of Asian Studies. 30: 203–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2016.

- Dorothy Ko (2008). Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding. University of California Press. pp. 14–16. ISBN 978-0-520-25390-2.

- Vincent Goossaert; David A. Palmer (15 April 2011). The Religious Question in Modern China. University of Chicago Press. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-226-30416-8. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- Levy, Howard S. (1991). The Lotus Lovers: The Complete History of the Curious Erotic Tradition of Foot Binding in China. New York: Prometheus Books. p. 322.

- Guangqiu Xu (2011). American Doctors in Canton: Modernization in China, 1835–1935. Transaction Publishers. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-4128-1829-2.

- Connie A. Shemo (2011). The Chinese Medical Ministries of Kang Cheng and Shi Meiyu, 1872–1937. Lehigh University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-61146-086-5.

- Mary Keng Mun Chung (1 May 2005). Chinese Women in Christian Ministry. Peter Lang Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-0-8204-5198-5.

- "1907: Qiu Jin, Chinese feminist and revolutionary". ExecutedToday.com. July 15, 2011.

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony (2010-10-22). "The Art of Social Change: Campaigns against foot-binding and genital mutilation". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-09-03.

- "Cixi Outlaws Foot Binding", History Channel

- Dorothy Ko (2008). Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding. University of California Press. pp. 50–63. ISBN 978-0-520-25390-2.

- Wang Ke-wen (1996). Thomas Reilly; Jens Bangsbo; A Mark Williams (eds.). Science and Football III. Taylor & Francis. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-419-22160-9.

- Mary White Stewart (27 January 2014). Ordinary Violence: Everyday Assaults against Women Worldwide. Praeger. pp. 4237–428. ISBN 978-1-4408-2937-6.

- Margaret E. Keck, Kathryn Sikkink (1998). Activists beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Cornell University Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-8014-8456-8.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Sidney D. Gamble (September 1943). "The Disappearance of Foot-Binding in Tinghsien". American Journal of Sociology. 49 (2): 181–183. doi:10.1086/219351. JSTOR 2770363.

- Hu, Alex. The Influence of Western Women on the Anti-Footbinding Movement. Historical Reflections, Vol. 8, No. 3, Women in China: Current Directions in Historical Scholarship, Fall 1981, pp. 179-199. " Besides improvements in civil engineering, progress was made in social areas as well. The traditional Chinese practice of foot binding was widespread in Taiwan's early years. Traditional Chinese society perceived women with smaller feet as being more beautiful. Women would bind their feet with long bandages to stunt growth. Even housemaids were divided into those with bound feet and those without. The former served the daughters of the house, while the latter were assigned heavier work. This practice was later regarded as barbaric. In the early years of the Japanese colonial period, the Foot-binding Liberation Society was established to promote the idea of natural feet, but its influence was limited. The fact that women suffered higher casualties in the 1906 Meishan quake with 551 men and 700 women dead, and 1,099 men and 1,334 women injured--very different from the situation in Japan--raised public concern. Foot binding was blamed and this gave impetus to the drive to stamp out the practice."

- Favazza, Armando R. Bodies under Siege: Self-mutilation, Nonsuicidal Self-injury, and Body Modification in Culture and Psychiatry (2011), p. 118.

- "In China, foot binding slowly slips into history". Kit Gillet. Los Angeles Times. April 2012.

- "Women with Bound Feet in China". University of Virginia.

- Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding. Ko, Alice. University of California Press. 2007. 978-0520253902. "The last case of girls binding ever occurred in 1957.

- "Unbound: China's last 'lotus feet' – in pictures". The Guardian. 15 June 2015.

- David Rosenberg (May 21, 2015). "Traveling Across China to Tell the Story of a Generation of Women With Bound Feet". Slate.

- Dorothy Ko (2008). Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding. University of California Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-520-25390-2.

- Hill Gates (2014). Footbinding and Women's Labor in Sichuan. Routledge. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-415-52592-3.

- Hill Gates (2014). Footbinding and Women's Labor in Sichuan. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-415-52592-3.

- William Duiker; Jackson Spielvoge, eds. (2012). World History (7th Revised ed.). Wadsworth Publishing Co Inc. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-111-83165-3.

- Dorothy Ko (2008). Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding. University of California Press. pp. 111–115. ISBN 978-0-520-21884-0.

- Shepherd, John Robert (2019). Footbinding as Fashion: Ethnicity, Labor, and Status in Traditional China. University of Washington Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0295744414.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: the Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. pp. 246–249. ISBN 978-0-8047-3606-0.

- Lawrence Davis, Edward (2005). Encyclopedia of Contemporary Chinese Culture, Routledge, p. 333.

- James Hastings; John Alexander Selbie; Louis Herbert Gray (1916). Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8. EDINBURGH: T. & T. Clark. p. 893. Retrieved January 1, 2011.(Original from Harvard University)

- Touraj Atabaki, Sanjyot Mehendale; Sanjyot Mehendale (2005). Central Asia and the Caucasus: transnationalism and diaspora. Psychology Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-415-33260-6. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- James Legge (1880). The religions of China: Confucianism and Tâoism described and compared with Christianity. LONDON: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 111. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

mohammedan.

(Original from Harvard University) - Jackson, Beverley (1997). Splendid Slippers: A Thousand Years of an Erotic Tradition. Ten Speed Press. ISBN 978-0-89815-957-8.

- Margo DeMello (2007). Encyclopedia of Body Adornment. Greenwood Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-313-33695-9.

- Newham, Fraser (21 March 2005). "The ties that bind". The Guardian.

- Mary White Stewart (27 January 2014). Ordinary Violence: Everyday Assaults against Women Worldwide. Praeger. p. 423. ISBN 978-1-4408-2937-6.

- Cummings, S.R.; Ling, X; Stone, K (1997). "Consequences of foot binding among older women in Beijing, China". American Journal of Public Health. 87 (10): 1677–1679. doi:10.2105/AJPH.87.10.1677. PMC 1381134. PMID 9357353.

- Cummings, S. & Stone, K. (1997) "Consequences of Foot Binding Among Older Women in Beijing China", in: American Journal of Public Health EBSCO Host. Oct 1997

- Patricia Buckley Ebrey, “Gender and Sinology: Shifting Western Interpretations of Foot binding, 1300-1890,” ‘’ Late Imperial China’’ (1999) 20#2 pp 1-34.

- Shirley See Yan Ma (4 December 2009). Footbinding: A Jungian Engagement with Chinese Culture and Psychology. Taylor & Francis Ltd. pp. 75–78. ISBN 9781135190071.

- Beauchamp, Fay. "Asian Origins of Cinderella: The Zhuang Storyteller of Guangxi" (PDF). Oral Tradition. 25 (2): 447–496.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (2010). 'Cambridge Illustrated History of China (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 160–161. ISBN 9780521124331.

- King, Ian (31 March 2017). The Aesthetics of Dress. Springer. p. 59. ISBN 9783319543222.

- Hill Gates (2014). Footbinding and Women's Labor in Sichuan. Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-415-52592-3.

- Robert Hans van Gulik (1961). Sexual life in ancient China:A Preliminary Survey of Chinese Sex and Society from Ca. 1500 B.C. Till 1644 A.D. Brill. p. 218. ISBN 9004039171.

- Janell L. Carroll (2009). Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity. Cengage Learning. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-495-60499-0.

- Armando R. Favazza (2 May 2011). Bodies under Siege: Self-mutilation, Nonsuicidal Self-injury, and Body Modification in Culture and Psychiatry (third ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 117. ISBN 9781421401119.

- Hacker, Authur (2012). China Illustrated. Turtle Publishing. ISBN 9781462906901.

- Patricia Buckley Ebrey (19 September 2002). Women and the Family in Chinese History. Routledge. pp. 10–12. ISBN 978-0415288224.

- Anders Hansson (1996). Chinese Outcasts: Discrimination and Emancipation in Late Imperial China. Brill. p. 46. ISBN 978-9004105966.

- Li-Hsiang Lisa Rosenlee (April 2006). Confucianism and Women: A Philosophical Interpretation. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-7914-6749-7.

- Bonnie G. Smith (2008). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History: 4 Volume Set. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 358–. ISBN 978-0-19-514890-9.

- 丁传靖 编 (1981). 《宋人轶事汇编》. 北京: 中华书局. p. 卷9,第2册,页455.

- Bin Song (16 March 2017). "Foot-binding and Ruism (Confucianism)". Huffington Post.

- Tu Wei-ming (1985). Confucian thought: selfhood as creative transformation. State University of New York Press.

- C. Fred Blake (1994). "Foot-Binding in Neo-Confucian China and the Appropriation of Female Labor" (PDF). Signs. 19 (3): 676–712. doi:10.1086/494917.

- Ko, Dorothy (1997). "The Body as Attire: The Shifting Meanings of Footbinding in Seventeenth-Century China" (PDF). Journal of Women's History. 8 (4): 8–27. doi:10.1353/jowh.2010.0171.

- Valerie Steele; John S. Major (2000). China Chic: East Meets West. Yale University Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-300-07931-9.

- Dorothy Ko (1994). Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-century China. Stanford University Press. pp. 149–. ISBN 978-0-8047-2359-6.

- Li-Hsiang Lisa Rosenlee (February 2012). Confucianism and Women: A Philosophical Interpretation. SUNY Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780791481790.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Fan Hong (2013-04-03). Footbinding, Feminism and Freedom: The Liberation of Women's Bodies in Modern China. Routledge. ISBN 9781136303142.

- Mary White Stewart (27 January 2014). Ordinary Violence: Everyday Assaults against Women Worldwide (2nd ed.). Praeger. pp. 423–437. ISBN 9781440829383.

- Claire M. Renzetti; Jeffrey L. Edleson, eds. (6 August 2008). Encyclopedia of Interpersonal Violence. 1. SAGE Publications. p. 276–277. ISBN 978-1412918008.

- Laura L. O'Toole; Jessica R. Schiffman, eds. (1 March 1997). Gender Violence: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. New York University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0814780411.

- Fairbank, John King (1986). The Great Chinese Revolution, 1800–1985. New York: Harper & Row. p. 70.

- Le, Huy Anh S. (2014). "Revisiting Footbinding: The Evolution of the Body as Method in Modern Chinese History". Inquiries Journal. 6 (10).

- Hong Fan (1 June 1997). Footbinding, Feminism, and Freedom: The Liberation of Women's Bodies in Modern China. Routledge. pp. 90–96. ISBN 978-0714646336.

- Hong Fan (1 June 1997). Footbinding, Feminism, and Freedom: The Liberation of Women's Bodies in Modern China. Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-0714646336.

- Patricia Buckley Ebrey, “Gender and Sinology: Shifting Western Interpretations of Foot binding, 1300-1890,” ‘’ Late Imperial China’’ (1999) 20#2 pp 1-34.

- Dorothy Ko, "Rethinking sex, female agency, and footbinding", Research on Women in Modern Chinese History / Jindai Zhongguo Funu Shi Yanjiu (1999), Vol. 7, pp 75–105

- Colleen Walsh (December 9, 2011). "Unraveling a brutal custom". Harvard Gazette.

- Hill Gates (2014). Footbinding and Women's Labor in Sichuan. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-52592-3.

- Dorothy Ko (2008). Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding. University of California Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-520-25390-2.

- Mei Ching Liu, "Women and the Media in China: An Historical Perspective", Journalism Quarterly 62 (1985): 45-52.

- Patricia Ebrey, "Gender and Sinology: Shifting Western Interpretations of Footbinding, 1300–1890", Late Imperial China 20.2 (1999): 1-34.

- The Golden Lotus, Volume 1. Singapore: Graham Brash (PTE) Ltd. 1979. p. 101.

- Ruzhen Li (1965). Flowers in the Mirror. translation by Lin Tai-yi. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-00747-5.

- Jicai, Feng & Wakefield, David (Translator) (1994). The Three Inch Lotus. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Children's Book Review: Ties That Bind, Ties That Break by Lensey Namioka". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

Notes

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Berger, Elizabeth, Liping Yang, and Wa Ye. "Foot binding in a Ming dynasty cemetery near Xi’an, China." International journal of paleopathology 24 (2019): 79–88. online

- Bossen, Laurel, and Hill Gates. Bound feet, young hands: tracking the demise of footbinding in village China (Stanford University Press, 2017).

- Brown, Melissa J., and Damian Satterthwaite-Phillips. "Economic correlates of footbinding: Implications for the importance of Chinese daughters’ labor." PloS one 13.9 (2018): e0201337. online

- Brown, Melissa J. et al., “Marriage Mobility and Footbinding in Pre-1949 Rural China: A Reconsideration of Gender, Economics, and Meaning in Social Causation." Journal of Asian Studies (2012), Vol. 71 Issue 4, pp 1035–1067

- Berg, Eugene E., MD, Chinese Footbinding. Radiology Review – Orthopaedic Nursing 24, no. 5 (September/October) 66–67

- Fan Hong (1997) Footbinding, Feminism and Freedom. London: Frank Cass

- Hughes, Roxane. "Ambivalent Orientalism: Footbinding in Chinese American History, Culture and Literature". (Diss. Université de Lausanne, Faculté des lettres, 2017) online.

- Ko, Dorothy (2005) Cinderella’s Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Ko, Dorothy (2008). "Perspectives on Foot-binding" (PDF). ASIANetwork Exchange. XV (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2011.

- Levy, Howard S. (1991). The Lotus Lovers: The Complete History of the Curious Erotic Tradition of Foot Binding in China. New York: Prometheus Books.

- Ping, Wang. Aching for Beauty: Footbinding in China. New York: Anchor Books, 2002.

- Shepherd, John R. "The Qing, the Manchus, and Footbinding: Sources and Assumptions under Scrutiny." Frontiers of History in China 11.2 (2016): 279–322.

- Robert Hans van Gulik (1961). Sexual life in ancient China:A Preliminary Survey of Chinese Sex and Society from Ca. 1500 B.C. Till 1644 A.D. Brill. ISBN 9004039171.

- Collection of bound foot shoes Article on Yang Shaorong, collector of bound foot shoes. Includes images of peasant/winter models and western-style models.

- The Virtual Museum of The City of San Francisco, Chinese Foot Binding – Lotus Shoes