Qiu Jin

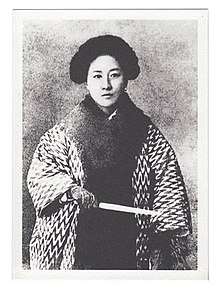

Qiu Jin (Chinese: 秋瑾; pinyin: Qiū Jǐn; Wade–Giles: Ch'iu Chin; November 8, 1875 – July 15, 1907) was a Chinese revolutionary, feminist, and writer. Her courtesy names are Xuanqing (Chinese: 璿卿; pinyin: Xuánqīng) and Jingxiong (simplified Chinese: 竞雄; traditional Chinese: 競雄; pinyin: Jìngxióng). Her sobriquet name is Jianhu Nüxia (simplified Chinese: 鉴湖女侠; traditional Chinese: 鑑湖女俠; pinyin: Jiànhú Nǚxiá) which, when translated literally into English, means "Woman Knight of Mirror Lake". Qiu was executed after a failed uprising against the Qing dynasty, and she is considered a national heroine in China; a martyr of republicanism and feminism.

Qiu Jin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 8 November 1875 |

| Died | 15 July 1907 (aged 31) |

| Cause of death | Execution by Decapitation |

| Political party | Guangfuhui Tongmenghui |

| Spouse(s) | Wang Tingjun |

| Children | Wang Yuande (王沅德) Wang Guifen (王桂芬) |

| Parent(s) | Qiu Xinhou (秋信候) |

Biography

Born in Xiamen, Fujian, China,[1] Qiu spent her childhood in her ancestral home,[2] Shaoxing, Zhejiang. While in an unhappy marriage, Qiu came into contact with new ideas. She became a member of the Tongmenghui secret society[3] who at the time advocated the overthrow of the Qing and restoration of Han Chinese governance.

In 1903, she decided to travel overseas and study in Japan,[4] leaving her two children behind. She initially entered a Japanese language school in Surugadai, but later transferred to the Girls' Practical School in Kōjimachi, run by Shimoda Utako.[5] Qiu was fond of martial arts, and she was known by her acquaintances for wearing Western male dress[6][7][1] and for her nationalist, anti-Manchu ideology. She joined the anti-Qing society Guangfuhui, led by Cai Yuanpei, which in 1905 joined together with a variety of overseas Chinese revolutionary groups to form the Tongmenghui, led by Sun Yat-sen.

Within this Revolutionary Alliance, Qiu was responsible for the Zhejiang Province. Because the Chinese overseas students were divided between those who wanted an immediate return to China to join the ongoing revolution and those who wanted to stay in Japan to prepare for the future, a meeting of Zhejiang students was held to debate the issue. At the meeting, Qiu allied unquestioningly with the former group and thrust a dagger into the podium, declaring, "If I return to the motherland, surrender to the Manchu barbarians, and deceive the Han people, stab me with this dagger!" She subsequently returned to China in 1906 along with about 2,000 students.[8]

Whilst still based in Tokyo, Qiu single-handedly edited a journal, Vernacular Journal (Baihua Bao). A number of issues were published using vernacular Chinese as a medium of revolutionary propaganda. In one issue, Qiu wrote A Respectful Proclamation to China's 200 Million Women Comrades, a manifesto within which she lamented the problems caused by bound feet and oppressive marriages[9]. Having suffered from both ordeals herself, Qiu explained her experience in the manifesto and received an overwhelmingly sympathetic response from her readers.[10] Also outlined in the manifesto was Qiu's belief that a better future for women lay under a Western-type government instead of the Qing government that was in power at the time. She joined forces with her cousin Xu Xilin[6] and together they worked to unite many secret revolutionary societies to work together for the overthrow of the Qing dynasty.

She was known as an eloquent orator[11] who spoke out for women's rights, such as the freedom to marry, freedom of education, and abolishment of the practice of foot binding. In 1906 she founded China Women's News (Zhongguo nü bao), a radical women's journal with another female poet, Xu Zihua.[12] They published only two issues before it was closed by the authorities.[13] In 1907 she became head of the Datong school in Shaoxing, ostensibly a school for sport teachers, but really intended for the military training of revolutionaries.

Death

On July 6, 1907, Xu Xilin was caught by the authorities before a scheduled uprising in Anqing. He confessed his involvement under torture and was executed. On July 12, the authorities arrested Qiu at the school for girls where she was the principal. She was tortured as well but refused to admit her involvement in the plot. Instead the authorities used her own writings as incrimination against her and, a few days later, she was publicly beheaded in her home village, Shanyin, at the age of 31[2]. Her last written words, her death poem, uses the literal meaning of her name, Autumn Gem, to lament of the failed revolution that she would never see take place:

"秋風秋雨愁煞人" ("Autumn wind, autumn rain — they make one die of sorrow")[14]

Legacy

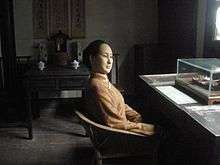

Qiu was immortalised in the Republic of China's popular consciousness and literature after her death. She is now buried beside West Lake in Hangzhou. The People's Republic of China established a museum for her in Shaoxing, named after Qiu Jin's Former Residence (绍兴秋瑾故居).

Her life has been portrayed in plays, popular movies (including the 1972 Hong Kong film Chow Ken (秋瑾)), and the documentary Autumn Gem.[15] One film, simply entitled Qiu Jin, was released in 1983 and directed by Xie Jin;[16][17]. Another film, released in 2011, was entitled Jing Xiong Nüxia Qiu Jin (竞雄女侠秋瑾), or The Woman Knight of Mirror Lake, and directed by Herman Yau. She is briefly shown in the beginning of 1911, being led to the execution ground to be beheaded. The movie was directed by Jackie Chan and Zhang Li. Immediately after her death Chinese playwrights used the incident, "resulting in at least eight plays before the end of the Ch'ing dynasty."[18]

In 2018, The New York Times published a belated obituary for her.[19]

Literary works

Because Qiu is mainly remembered in the West as revolutionary and feminist, her poetry and essays are often overlooked (though owing to her early death, they are not great in number). Her writing reflects an exceptional education in classical literature, and she writes traditional poetry (shi and ci). Qiu composes verse with a wide range of metaphors and allusions that mix classical mythology with revolutionary rhetoric.

For example, in a poem, Capping Rhymes with Sir Ishii From Sun's Root Land[20] we read the following:

| Chinese | English [21] |

|---|---|

|

漫云女子不英雄, |

Don't tell me women are not the stuff of heroes, |

Editors Sun Chang and Saussy explain the metaphors as follows:

- line 4: "Your islands" translates "sandao," literally "three islands," referring to Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu, while omitting Hokkaido - an old fashion way of referring to Japan.

- line 6: ... the conditions of the bronze camels, symbolic guardians placed before the imperial palace, is traditionally considered to reflect the state of health of the ruling dynasty. But in Qiu's poetry, it reflects instead the state of health of China.[22]

On leaving Beijing for Japan, she wrote a poem summarizing her life until that point:

| Chinese | English [23] |

|---|---|

|

日月無光天地昏,

沉沉女界有誰援。 |

Sun and moon have no light left, earth is dark; |

Further reading

- Laure deShazer, Marie. Qiu Jin, Chinese Joan of Arc. ISBN 978-1537157085.

See also

Footnotes

- Schatz, Kate; Klein Stahl, Miriam (2016). Rad women worldwide: artists and athletes, pirates and punks, and other revolutionaries who shaped history. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. p. 13.

- Porath, Jason (2016). Rejected princesses: tales of history's boldest heroines, hellions, and heretics. New York: Dey Street Press. p. 272.

- Porath, Jason (2016). Rejected princesses: tales of history's boldest heroines, hellions, and heretics. New York: Dey Street Press. p. 271.

- Barnstone, Tony; Ping, Chou (2005). The Anchor Book of Chinese Poetry. New York: Anchor Books. p. 344.

- Ono, Kazuko (1989). Chinese Women in a Century of Revolution, 1850-1950. Stanford University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780804714976.

- Ashby, Ruth; Gore Ohrn, Deborah (1995). Herstory: Women Who Changed the World. New York: Viking Press. p. 181.

- Porath, Jason (2016). Rejected princesses: tales of history's boldest heroines, hellions, and heretics. New York. p. 271.

- Ono, Kazuko (1989). Chinese Women in a Century of Revolution, 1850-1950. Stanford University Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN 9780804714976.

- Dooling, Amy D (2005). Women's literary feminism in twentieth-century China. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 52.

- Ono, Kazuko (1989). Chinese Women in a Century of Revolution, 1850-1950. Stanford University Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9780804714976.

- Dooling, Amy D. (2005). Women’s Literary Feminism in Twentieth-Century China. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 50.

- Zhu, Yun (2017). Imagining Sisterhood in Modern Chinese Texts, 1890–1937. Lanham: Lexington Books. p. 38.

- Fincher, Leta Hong (2014). Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China. London, New York: Zed Books. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-78032-921-5.

- Yan, Haiping (2006). Chinese women writers and the feminist imagination, 1905-1948. New York: Routledge. p. 33.

- Tow, Adam (2017). Autumn Gem. San Francisco: Kanopy.

- Browne, Nick; Pickowicz, Paul G.; Yau, Esther (eds.). New Chinese Cinemas: Forms, Identities, Politics. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0 521 44877 8.

- Kuhn, Annette; Radstone, Susannah (eds.). The Women's Companion to International Film. University of California Press. p. 434. ISBN 0520088794.

- Mair, Victor H. (2001). The Columbia history of Chinese literature. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 844.

- Qin, Amy (2018). "Qiu Jin, Beheaded by Imperial Forces, Was 'China's Joan of Arc'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-03-09 – via nytimes.com.

- Ayscough, Florence (1937). Chinese Women: yesterday & to-day. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 147.

- translated by Zachary Jean Chartkoff

- Chang, Kang-i Sun; Saussy, Haun (1999). Women Writers of Traditional China: An Anthology of Poetry and Criticism. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 642.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1981). The Gate of Heavenly Peace. Penguin Books. p. 85.

External links

- The Qiu Jin Museum (archived) from chinaspirit.net.cn

- Autumn Gem, documentary film