Necrophilia

Necrophilia, also known as necrophilism, necrolagnia, necrocoitus, necrochlesis, and thanatophilia,[1] is sexual attraction towards or a sexual act involving corpses. It is classified as a paraphilia by the World Health Organization (WHO) in its International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic manual, as well as by the American Psychiatric Association[2] in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM).

| Necrophilia | |

|---|---|

| |

| The Hatred, painted by Pietro Pajetta, 1896. | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Origins of term

Various terms for the crime of corpse-violation animate sixteenth- through nineteenth-century works on law and legal medicine.[3] The plural term "nécrophiles" was coined by Belgian physician Joseph Guislain in his lecture series, Leçons Orales Sur Les Phrénopathies, given around 1850, about the contemporary necrophiliac François Bertrand:[4]

It is within the category of the destructive madmen [aliénés destructeurs] that one needs to situate certain patients to whom I would like to give the name of necrophiliacs [nécrophiles]. The alienists have adopted, as a new form, the case of Sergeant Bertrand, the disinterrer of cadavers on whom all the newspapers have recently reported. However, don't think that we are dealing here with a form of phrenopathy which appears for the first time. The ancients, in speaking about lycanthropy, have cited examples to which one can more or less relate the case which has just now attracted the public attention so strongly.

Psychiatrist Bénédict Morel popularised the term about a decade later when discussing Bertrand.[2]

History

In the ancient world, sailors returning corpses to their home country were often accused of necrophilia.[5] Singular accounts of necrophilia in history are sporadic, though written records suggest the practice was present within Ancient Egypt. Herodotus writes in The Histories that, to discourage intercourse with a corpse, ancient Egyptians left deceased beautiful women to decay for "three or four days" before giving them to the embalmers.[6][7][8] Herodotus also alluded to suggestions that the Greek tyrant Periander had defiled the corpse of his wife, employing a metaphor: "Periander baked his bread in a cold oven."[9] Acts of necrophilia are depicted on ceramics from the Moche culture, which reigned in northern Peru from the first to eighth century CE.[10] A common theme in these artifacts is the masturbation of a male skeleton by a living woman.[11] Hittite law from the 16th century BC through to the 13th century BC explicitly permitted sex with the dead.[12] In what is now Northeast China, the ethnic Xianbei emperor Murong Xi (385–407) of the Later Yan state had intercourse with the corpse of his beloved empress Fu Xunying, after the latter was already cold and put into the coffin.[13]

In Renaissance Italy, following the reputed moral collapse brought about by the Black Death and before the Roman Inquisition of the Counter-Reformation, literature was replete with sexual references; these include necrophilia, as in the epic poem Orlando Innamorato by Matteo Maria Boiardo, first published in 1483.[14] In a notorious modern example, American serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer was a necrophiliac. Dahmer wanted to create a sex slave who would mindlessly consent to whatever he wanted. When his attempts failed, and his male victim died, he would keep the corpse until it decomposed beyond recognition, continuously masturbating and performing sexual intercourse on the body.[15] To be aroused, he had to murder his male victims before performing sexual intercourse with them. Dahmer stated that he only killed his victims because they wanted to leave after having sex, and would be angry with him for drugging them.[16] British serial killer Dennis Nilsen is also considered to have been a necrophiliac.[17]

Classification

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), recurrent, intense sexual interest in corpses can be diagnosed under Other Specified Paraphilic Disorder (necrophilia) when it causes marked distress or impairment in important areas of functioning.[18] A ten-tier classification of necrophilia exists:[19]

- Role players: People who get aroused when pretending their partner is dead during sexual activity.

- Romantic necrophiliacs: Bereaved people who remain attached to their dead lover's body.

- Necrophiliac fantasisers: People who fantasise about necrophilia, but do not physically interact with corpses.

- Tactile necrophiliacs: People who are aroused by touching or stroking a corpse, without engaging in intercourse.

- Fetishistic necrophiliacs: People who remove objects (e.g., panties or a tampon) or body parts (e.g., a finger or genitalia) from a corpse for sexual purposes, without engaging in intercourse.

- Necromutilomaniacs: People who derive pleasure from mutilating a corpse while masturbating, without engaging in intercourse.

- Opportunistic necrophiliacs: People who normally have no interest in necrophilia, but take the opportunity when it arises.

- Regular necrophiliacs: People who preferentially have intercourse with the dead.

- Homicidal necrophiliacs: Necrosadists,[20] people who murder someone in order to have sex with the victim.

- Exclusive necrophiliacs: People who have an exclusive interest in sex with the dead, and cannot perform at all for a living partner.

Additionally, criminologist Lee Mellor's typology of homicidal necrophiliacs consists of eight categories (A–H) and is based on the combination of two behavioural axes: destructive (offender mutilates the corpse for sexual reasons) – preservative (offender does not), and cold (offender used the corpse sexually two hours after death) – warm (offender used the corpse sexually earlier than two hours after death).[21] This renders four categories (A-D) to which Mellor adds an additional four (E-H):

- Category A (cold/destructive), e.g. Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer

- Category B (cold/preservative), e.g. Gary Ridgway, Dennis Nilsen

- Category C (warm/destructive) e.g. Andrei Chikatilo, Joseph Vacher

- Category D (warm/preservative) e.g. Robert Yates, Earle Nelson

- Category E (dabblers) e.g. Richard Ramirez, Mark Dixie

- Category F (catathymic — impulsively and explosively lashing out)

- Category G (exclusive necromutilophiles) e.g. Robert Napper, Peter Sutcliffe

- Category H (sexual cannibals & vampires) e.g. Albert Fish, Peter Kürten[21]

Dabblers have transitory opportunistic sexual relations with corpses, but do not prefer them. Catathymic necrophiliacs commit postmortem sex acts only while in a sudden impulsive state. Exclusive necromutilophiles derive pleasure purely from mutilating the corpse, while sexual cannibals and vampires are sexually aroused by eating human body parts. Category A, C, and F offenders may also cannibalise or drink the blood of their victims.[21]

Research

Humans

Necrophilia is often assumed to be rare, but no data for its prevalence in the general population exists.[22] Some necrophiliacs only fantasise about the act, without carrying it out.[23] In 1958, Klaf and Brown commented that, although rarely described, necrophiliac fantasies may occur more often than is generally supposed.[24]

Rosman and Resnick (1989) reviewed 122 cases of necrophilia. The sample was divided into genuine necrophiliacs, who had a persistent attraction to corpses, and pseudo-necrophiliacs, who acted out of opportunity, sadism, or transient interest. Of the total, 92% were male and 8% were female. 57% of the genuine necrophiliacs had occupational access to corpses, with morgue attendants, hospital orderly, and cemetery employees being the most common jobs. The researchers theorised that either of the following situations could be antecedents to necrophilia:[23]

- The necrophiliac develops poor self-esteem, perhaps due in part to a significant loss;

- (a) They are very fearful of rejection by others and they desire a sexual partner who is incapable of rejecting them; and/or

- (b) They are fearful of the dead, and transform their fear—by means of reaction formation—into a desire.

- They develop an exciting fantasy of sex with a corpse, sometimes after exposure to a corpse.

Motives

The most common motive for necrophiliacs is the possession of a partner who is unable to resist or reject them. However, in the past, necrophiliacs have expressed having more than one motive.[25]

The authors reported that of their sample of genuine necrophiliacs:[23]

- 68% were motivated by a desire for a non-resisting and non-rejecting partner

- 21% were motivated by a want for a reunion with a lost partner

- 15% were motivated by sexual attraction to dead people

- 15% were motivated by a desire for comfort or to overcome feelings of isolation

- 12% were motivated by a desire to remedy low self-esteem by expressing power over a corpse

Lesser common motives include:

- Unavailability of a living partner

- Compensation for a fear of women

- Belief that sex with a living woman was a mortal sin

- Need to achieve a feeling of total control over a sexual partner

- Compliance with a command hallucination

- Performance of a series of destructive acts

- Expression of polymorphous perverse sexual desires

- Need to perform limitless sexual activity[25]

IQ data was limited, but not abnormally low. About half of the sample had a personality disorder, and 11% of true necrophiliacs were psychotic. Rosman and Resnick concluded that their data challenged the conventional view of necrophiliacs as generally psychotic, mentally deficient, or unable to obtain a consenting partner.[23]

Rosman and Resnick (1989) reviewed information from 34 cases of necrophilia describing the individuals' motivations for their behaviours. These individuals reported the desire to possess a non-resisting and non-rejecting partner (68%), reunions with a deceased romantic partner (21%), sexual attraction to corpses (15%), overcoming feelings of isolation (15%), and seeking self-esteem by expressing power over a homicide victim (12%).[26]

Other animals

Necrophilia has been observed in mammals, birds, reptiles and frogs.[28] In 1960, Robert Dickerman described necrophilia in ground squirrels, which he termed "Davian behaviour" in reference to a limerick about a necrophiliac miner named Dave. The label is still used for necrophilia in animals.[29] Certain species of arachnids and insects practice sexual cannibalism, where the female cannibalises her male mate before, during, or after copulation.

Kees Moeliker made an observation while he was sitting in his office at the Natural History Museum Rotterdam, when he heard the distinctive thud of a bird hitting the glass facade of the building. Upon inspection, he discovered a drake (male) mallard lying dead outside the building. Next to the downed bird, a second drake mallard was standing close by. As Moeliker observed the couple, the living drake pecked at the corpse of the dead one for a few minutes then mounted the corpse and began copulating with it. The act of necrophilia lasted for about 75 minutes, in which time, according to Moeliker, the living drake took two short breaks before resuming with copulating behaviour. Moeliker surmised that at the time of the collision with the window the two mallards were engaged in a common pattern in duck behaviour called "attempted rape flight". "When one died the other one just went for it and didn't get any negative feedback – well, didn't get any feedback," according to Moeliker.[30][31] Necrophilia had previously only been reported in heterosexual mallard pairs.[30]

In a short paper known as "Sexual Habits of the Adélie Penguin", deemed too shocking for contemporary publication, George Murray Levick described "little hooligan bands" of penguins mating with dead females in the Cape Adare rookery, the largest group of Adélie penguins, in 1911 and 1912.[32][33] This is nowadays ascribed to lack of experience of young penguins; a dead female, with eyes half-closed, closely resembles a compliant female.[34] A gentoo penguin was observed attempting to have intercourse with a dead penguin in 1921.[35]

A male New Zealand sea lion was once observed attempting to copulate with a dead female New Zealand fur seal in the wild. The sea lion nudged the seal repeatedly, then mounted her and made several pelvic thrusts. Approximately ten minutes later, the sea lion became disturbed by the researcher's presence, dragged the corpse of the seal into the water, and swam away while holding it.[36] A male sea otter was observed holding a female sea otter underwater until she drowned before repeatedly copulating with her carcass. Several months later, the same sea otter was again observed copulating with the carcass of a different female.[37] Copulation with a dead female pilot whale by a captive male pilot whale has been observed,[38] and possible sexual behaviour between two male humpback whales, one dead, has also been reported.[39]

In 1983, a male rock dove was observed to be copulating with the corpse of a dove that shortly before had its head crushed by a car.[40][41] In 2001, a researcher laid out sand martin corpses to attract flocks of other sand martins. In each of six trials, 1–5 individuals from flocks of 50–500 were observed attempting to copulate with the dead sand martins. This occurred one to two months after the breeding season; since copulation outside the breeding season is uncommon among birds, the researcher speculated that the lack of resistance by the corpses stimulated the behaviour.[42] Charles Brown observed at least ten cliff swallows attempt to copulate with a road-killed cliff swallow in the space of 15 minutes. He commented, "This isn't the first time I've seen cliff swallows do this; the bright orange rump sticking up seems to be all the stimulus these birds need."[43] Necrophilia has also been reported in the European swallow, grey-backed sparrow-lark, Stark's lark,[33] and the snow goose.[44] A Norwegian television report showed a male hybrid between a black grouse and western capercaillie kill a male black grouse before attempting to copulate with it.[42] In 2015, due to work done by the University of Washington, it was found that crows would commit necrophilia on dead crow corpses in about 4% of encounters with corpses.[45]

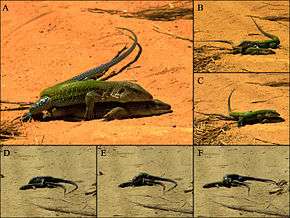

Necrophilia has been documented in various lizard species, including Ameiva ameiva,[29][46] the leopard lizard,[47] and Holbrookia maculata.[48] There are two reports of necrophilic behaviour in the sleepy lizard (Tiliqua rugosa). In one, the partner of a male lizard got caught in fencing wire and died. The male continued to display courtship behaviour towards his partner two days after her death. This lizard's necrophilia was believed to stem from its strong monogamous bond.[49] In one study of black and white tegu lizards, two different males were observed attempting to court and copulate with a single female corpse on two consecutive days. On the first day, the corpse was freshly dead, but by the second day it was bloating and emitting a strong putrid odor. The researcher attributed the behaviour to sex pheromones still acting on the carcass.[27]

Male garter snakes often copulate with dead females.[50][51] One case has been reported in the Bothrops jararaca snake with a dead South American rattlesnake.[52][53] The prairie rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis) and Helicops carinicaudus snake have both been seen attempting to mate with decapitated females, presumably attracted by still-active sex pheromones.[53][54] Male crayfish sometimes copulate with dead crayfish of either sex, and in one observation with a dead crayfish of a different species.[55][56]

In frogs, it has been observed in the foothill yellow-legged frog,[57] the yellow fire-bellied toad,[58] the common frog,[59] the Oregon spotted frog,[60] Dendropsophus columbianus,[61] and Rhinella jimi.[62] The film Cane Toads: An Unnatural History shows a male toad copulating with a female toad that had been run over by a car for eight hours.[63] Necrophilic amplexus in frogs may occur because males will mount any pliable object the size of an adult female. If the mounted object is a live frog not appropriate for mating, it will vibrate its body or vocalise a call to be released. Dead frogs cannot do this, so they may be held for hours.[59] The Amazonian frog Rhinella proboscidea sometimes practices what has been termed "functional necrophilia": a male grasps the corpse of a dead female and squeezes it until its oocytes are ejected before fertilising them.[64]

Treatment

Treatment for necrophilia is similar to that prescribed for most paraphilias. Besides advocating treatment of the associated psychopathology, there is little known on the treatment of necrophilia. There has not been a sufficient number of necrophiliacs to establish any effective treatments. However, based on the available data, clinicians are suggested to:

- Determine whether or not a patient has necrophilia

- Treat any psychopathology that is associated with necrophilia

- Establish psycho-therapeutic rapport

- Provide male patients with heightened sex drives with anti-androgens

- Help patients find a normal sexual relationship

- Help divert the necrophilic fantasies to a living object via desensitization[65]

Case studies

Jeffrey Dahmer

Jeffrey Dahmer was one of the most notorious American serial killers, sex offenders, and necrophiliacs. His fascination with death was present from childhood, during which he reportedly owned a collection of various bones. In 1978, Dahmer killed the first of several victims, later admitting to having had oral sex with some of the victims post-mortem.

Ted Bundy

Ted Bundy (born in November 1946) was an American serial killer who raped and murdered many young women during the 1970s. He also confessed to participating in necrophilic acts, claiming to have chosen secluded disposal sites for his victims' bodies specifically for post-mortem sexual intercourse.[66]

Karen Greenlee

Karen Greenlee (born 1956) is a female necrophilic criminal who was convicted of stealing a 1975 Cadillac hearse at a funeral and having sex with the corpse inside of it. She worked as an apprentice embalmer in Sacramento, California. On 17 December 1979, she stole the hearse along with the body of a 33-year-old man that was inside. She was sentenced to pay a $255 fine and 11 days in prison.

In 1987, Greenlee gave a detailed interview called “The Unrepentant Necrophile” for Jim Morton's (edited by Adam Parafrey) book Apocalypse Culture. In this interview, she stated that she had a preference for younger men and was attracted to the smell of blood and death. She considered necrophilia an addiction. The interview was held in her apartment, which was apparently a small studio filled with books, necrophilic drawings, and satanic adornments. She also had written a confession letter in which she claimed to have abused 20–40 male corpses.[67]

Dennis Nilsen

Dennis Nilsen (born in November 1945) was a Scottish serial killer and necrophiliac who murdered twelve young men between 1978 and 1983.

Following the death of his grandfather and his mother's explanation that the dead are in a "better place," Nilsen developed an association between death and intimacy, later finding posing as a corpse a source of sexual arousal. In 1978, Nilsen committed his first murder and enjoyed intercourse with the victim's corpse, keeping the body for months before disposal. Nilsen was reported to have sexually abused the corpses of various victims until his arrest.[66]

Legality

Australia

Necrophilia is not explicitly mentioned in Australian law; however, under the Crimes Act 1900 – Sect 81C, penalised for misconduct with regard to corpses is any person who:

(a) indecently interferes with any dead human body, or

(b) improperly interferes with, or offers any indignity to, any dead human body or human remains (whether buried or not), and

shall be liable to imprisonment for two years.[68]

Brazil

Article 212 of the Brazilian Penal Code (federal Decree-Law No 2.848) states as follows:[69][70]

Art. 212 – To abuse a cadaver or its ashes:

Penalty: detention, from 1 to 3 years, plus fine.

Although sex with a corpse is not explicitly mentioned, a person who has sex with a corpse may be convicted of a crime under the above Article. The legal asset protected by such Article is not the corpse's objective honour, but the feeling of good memories, respect, and veneration that living people keep about the deceased person: these persons are considered passive subjects of the corpse's violation.

India

Section 297 of the Indian Penal Code entitled "Trespassing on burial places, etc.", states as follows:[71]

Whoever, with the intention of wounding the feelings of any person, or of insulting the religion of any person, or with the knowledge that the feelings of any person are likely to be wounded, or that the religion of any person is likely to be insulted thereby, commits any trespass in any place of worship or on any place of sculpture, or any place set apart from the performance of funeral rites or as a depository for the remains of the dead, or offers any indignity to any human corpse, or causes disturbance to any persons assembled for the performance of funeral ceremonies, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to one year, or with fine, or with both.

Although sex with a corpse is not explicitly mentioned, a person who has sex with a corpse may be convicted under the above section. Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code can also be invoked.

New Zealand

Under Section 150 of the New Zealand Crimes Act 1961, it is an offence for there to be "misconduct in respect to human remains". Subsection (b) elaborates that this applies if someone "improperly or indecently interferes with or offers indignity to any dead human body or human remains, whether buried or not". This statute is therefore applicable to sex with corpses and carries a potential two-year prison sentence, although there is no relevant case law.[72]

South Africa

Section 14 of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act, 2007 prohibits the commission of a sexual act with a corpse.[73] Until codified by the act it was a common law offence.

Sweden

Section 16, § 10 of the Swedish Penal Code criminalises necrophilia, but it is not explicitly mentioned. Necrophilia falls under the regulations against abusing a corpse or grave (Brott mot griftefrid), which carries a maximum sentence of two years in prison. One person has been convicted of necrophilia. He was sentenced to psychiatric care for that and other crimes, including arson.[74]

United Kingdom

Sexual penetration of a corpse was made illegal under the Sexual Offences Act 2003, carrying a maximum sentence of two years' imprisonment. Prior to 2003, necrophilia was not illegal; however, exposing a naked corpse in public was classed as a public nuisance (R v. Clark [1883] 15 Cox 171).[75]

United States

There is no federal legislation specifically barring sex with a corpse. Multiple states have their own laws:[76][77]

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Necrophilia |

- Incidents of necrophilia

- Necrophilia in popular culture

- Vulnerability and care theory of love

- Death during consensual sex

- Karen Greenlee

- Sir Jimmy Savile

Footnotes

- Aggrawal 2016, p. 1.

- Goodwin, Robin; Cranmer, Duncan, eds. (2002). Inappropriate Relationships: The Unconventional, the Disapproved, and the Forbidden. London, England: Psychology Press. pp. 174–176. ISBN 978-0805837421.

- Janssen, Diederik F. (June 2020). "Medico-Forensic Pre-Histories of Sexual Perversion: The Case of Necrophilia (c. 1500–c. 1850)". Forensic Science International: Mind and Law: 100025. doi:10.1016/j.fsiml.2020.100025.

- Aggrawal 2016, p. 4.

- Aggrawal 2016, p. 2.

- Herodotus (c. 440 BC) (July 2001). The Histories (Book 2).

The wives of men of rank when they die are not given at once to be embalmed, nor such women as are very beautiful or of greater regard than others, but on the third or fourth day after their death (and not before) they are delivered to the embalmers. They do so about this matter in order that the embalmers may not abuse their women, for they say that one of them was taken once doing so to the corpse of a woman lately dead, and his fellow-craftsman gave information.

- Brill, Abraham A. (1941). "Necrophilia". Journal of Criminal Psychopathology. 2 (4): 433–443.

- Klaf, Franklin S.; Brown, William (1958). "Necrophilia: Brief Review and Case Report". Psychiatric Quarterly. 32 (4): 645–652. doi:10.1007/bf01563024. PMID 13634264.

Inhibited forms of necrophilia and necrophiliac fantasies may occur more commonly then is generally realised.

- Aggrawal 2010, pp. 6–7, The primary source is Histories, Book V, 92.

- Finbow, Steve (2014). Grave Desire: A Cultural History of Necrophilia. John Hunt Publishing. ISBN 9781782793410.

- Weismantel, M. (2004). "Moche sex pots: Reproduction and temporality in ancient South America" (PDF). American Anthropologist. 106 (3): 495–496. doi:10.1525/aa.2004.106.3.495.

- Boer, Roland (2014). "From Horse Kissing to Beastly Emissions: Paraphilias in the Ancient Near East". In Masterson, Mark (ed.). Sex in Antiquity: Exploring Gender and Sexuality in the Ancient World. Routledge. p. 69.

- Luan Pao-chün (1994). "The Corpse-Raping Emperor". Tales about Chinese Emperors: Their Wild and Wise Ways. Hai Feng Publishing Company. pp. 148–?.

- Davidson, Nicholas; Dean, Trevor; Lowe, K. J. P. (1994). Crime, Society and the Law in Renaissance Italy. pp. 74–98. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511523410.006. ISBN 9780511523410.

- "My Friend Dahmer #Full – Read My Friend Dahmer Issue #Full Page 214". www.comicextra.com. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Psychiatric Testimony of Jeffrey Dahmer". Court Transcripts. Criminal Profiling. 8 June 2001. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Masters, Brian (1985). Killing For Company. Arrow. ISBN 978-0099552611.

- American Psychiatric Association, ed. (2013). "Other Specified Paraphilic Disorder, 302.89 (F65.89)". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 705.

- Aggrawal, Anil (2009). "A new classification of necrophilia". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 16 (6): 316–20. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2008.12.023. PMID 19573840. (subscription required)

- Purcell & Arrigo 2006, p. 21.

- Mellor, Lee (2016). Homicide: A Forensic Psychology Casebook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC. pp. 103–105.

- Milner, J. S., Dopke, C. A., & Crouch, J. L. (2008). "Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified: Psychopathology and Theory". In Laws, D. Richard (ed.). Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment, 2nd edition. The Guilford Press. p. 399.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Resnick, Phillip J.; Soliman, Sherif (September 2012). "Planning, writing, and editing forensic psychiatric reports". International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 35 (5–6): 412–417. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2012.09.019. ISSN 0160-2527. PMID 23040708.

- Rosman, J. P.; Resnick, P. J. (1 June 1989). "Sexual attraction to corpses: A psychiatric review of necrophilia" (PDF/HTML). Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 17 (2): 153–163. PMID 2667656.

- Sazima, I. (2015). "Corpse bride irresistible: a dead female tegu lizard (Salvator merianae) courted by males for two days at an urban park in South-eastern Brazil". Herpetology Notes. 8: 15–18.

- de Mattos Brito, L. B., Joventino, I. R., Ribeiro, S. C., & Cascon, P. (2012). "Necrophiliac behaviour in the "Cururu" toad, Rhinella Jimi Steuvax, 2002, (Anura, Bufonidae) from Northeastern Brazil" (PDF). North-Western Journal of Zoology. 8 (2): 365.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Costa, H. C., da Silva, E. T., Campos, P. S., da Cunha Oliveira, M. P., Nunes, A. V., & da Silva Santos, P. (2010). "The corpse bride: a case of Davian behaviour in the green ameiva (Ameiva ameiva) in southeastern Brazil" (PDF). Herpetology Notes. 3: 79–83.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- C.W. Moeliker (2001). "The first case of homosexual necrophilia in the Anas platyrhynchos (Aves:Anatidae)" (PDF). Deinsea – Annual of the Natural History Museum Rotterdam. 8: 243–247. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- Donald MacLeod (8 March 2005). "Necrophilia among ducks ruffles research feathers". London: Guardian Unlimited. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2007.

- McKie, Robin (9 June 2012). "'Sexual depravity' of penguins that Antarctic scientist dared not reveal". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- Russell, D. G. D.; Sladen, W. J. L.; Ainley, D. G. (2012). "Dr. George Murray Levick (1876–1956): Unpublished notes on the sexual habits of the Adélie penguin". Polar Record. 48 (4): 1. doi:10.1017/S0032247412000216.

- McKie, Robin (9 June 2012). "'Sexual depravity' of penguins that Antarctic scientist dared not reveal". Guardian.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013.

- Bagshawe, T. W. (1938). "Notes on the Habits of the Gentoo and Ringed or Antarctic Penguins". The Transactions of the Zoological Society of London. 24 (3): 209. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1938.tb00391.x.

- Wilson, G. J. (1979). "Hooker's sea lions in southern New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 13 (3): 373–375. doi:10.1080/00288330.1979.9515812.

- Harris, H. S., Oates, S. C., Staedler, M. M., Tinker, M. T., Jessup, D. A., Harvey, J. T., & Miller, M. A. (2010). "Lesions and behaviour associated with forced copulation of juvenile Pacific harbor seals (Phoca Vitulina Richardsi) by southern sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis)" (PDF). Aquatic Mammals. 36 (4): 338. doi:10.1578/am.36.4.2010.331.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Brown, D. H. (1962). "Further observations on the pilot whale in captivity". Zoologica. 47 (1): 59–64.

- Pack, A. A., Salden, D. R., Ferrari, M. J., Glockner‐Ferrari, D. A., Herman, L. M., Stubbs, H. A., & Straley, J. M. (1998). "Male humpback whale dies in competitive group". Marine Mammal Science. 14 (4): 861–873. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1998.tb00771.x.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Slavid, Evelyn; Taylor, Julie (1987). "Feral Rock Dove displaying to and attempting to copulate with corpse of another" (PDF). British Birds. 8 (10): 497.

- "Randy rock doves join party with the dead". The Guardian. London. 14 March 2005. Retrieved 17 June 2007.

- Dale, S. (2001). "Necrophilic behaviour, corpses as nuclei of resting flock formation, and road-kills of Sand Martins Riparia riparia" (PDF). Ardea. 89 (3): 545–547.

- Charles Robert Brown (1998). Swallow Summer. University of Nebraska Press. p. 143.

- McKinney, F., & Evarts, S. (1998). "Sexual coercion in waterfowl and other birds". Ornithological Monographs (49): 163–195. doi:10.2307/40166723. JSTOR 40166723.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) The primary source (Gauthier & Tardif, 1991) states that "a paired male attempted to mount a recently shot bird used to attract other geese."

- Yong, Ed (18 July 2018). "Crows Sometimes Have Sex With Their Dead". The Atlantic. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Vitt, L.J. (2003). "Life versus sex: the ultimate choice". Lizards: Windows to the Evolution of Diversity. University of California Press. p. 103.

- Fallahpour, K. (2005). "Gambelia wislizenii. Necrophilia". Herpetological Review. 36: 177–178. Cited in Sazima (2015).

- Brinker, A.M, Bucklin, S.E. (2006). "Holbrookia maculata. Necrophilia". Herpetological Review. 37: 466.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cited in Sazima (2015).

- Bull, C. Michael (2000). "Monogamy in lizards" (PDF). Behavioural Processes. 51 (1): 12. doi:10.1016/s0376-6357(00)00115-7.

- Shine, R., O'Connor, D., & Mason, R. T. (2000). "Sexual conflict in the snake den" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 48 (5): 397. doi:10.1007/s002650000255. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2015.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Joy, J. E., & Crews, D. (1985). "Social dynamics of group courtship behavior in male red-sided garter snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis parietalis)". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 99 (2): 148. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.99.2.145.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Amaral. A. (1932). "Contribuição à biologia dos ophidios do Brasil. IV. Sobre um caso de necrophilia heterologa na jararaca (Bothrops jararaca)". Memórias do Instituto de Butantan. 7: 93–94. Cited in Costa et al. (2010).

- Klauber, Laurence Monroe (1972). Rattlesnakes: Their Habits, Life Histories, and Influence on Mankind, Volume 1. University of California Press. p. 718. ISBN 9780520017757.

- Santos, S. M. A., Siqueira, R., Coeti, R. Z., Cavalheri, D., & Trevine, V. (2015). "The sexual attractiveness of the corpse bride: unusual mating behaviour of Helicops carinicaudus (Serpentes: Dipsadidae)". Herpetology Notes. 8: 643–647.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pearse, A. S. (1909). "Observations on copulation among crawfishes with special reference to sex recognition". American Naturalist. 43 (516): 752. doi:10.1086/279107.

- Andrews, E. A. (1910). "Conjugation in the crayfish, Cambarus affinis". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 9 (2): 235–264. doi:10.1002/jez.1400090202.

- Bettaso, J., Haggarthy, A., Russel, E. (2008). "Rana boylii (Foothill Yellow-legged Frog). Necrogamy". Herpetological Review. 39: 462.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cited in Costa et al. (2010).

- Sinovas, P. (2009). "Bombina variegata (Yellow Fire-bellied Toad). Mating Behaviour". Herpetological Review. 40: 199. Cited in Costa et al. (2010).

- Mollov, I. A., Popgeorgiev, G. S., Naumov, B. Y., Tzankov, N. D., & Stoyanov, A. Y. (2010). "Cases of abnormal amplexus in anurans (Amphibia: Anura) from Bulgaria and Greece" (PDF). Biharean Biologist. 4 (2): 121–125.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pearl, C. A., Hayes, M. P., Haycock, R., Engler, J. D., & Bowerman, J. (2005). "Observations of interspecific amplexus between western North American ranid frogs and the introduced American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) and an hypothesis concerning breeding interference". The American Midland Naturalist. 154 (1): 126–134. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(2005)154[0126:ooiabw]2.0.co;2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Bedoya, S. C., Mantilla-Castaño, J. C., & Pareja-Márquez, I. M. (2014). "Necrophiliac and interspecific amplexus in Dendropsophus columbianus (Anura: Hylidae) in the Central Cordillera of Colombia" (PDF). Herpetology Notes. 7: 515–516.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- de Mattos Brito, L. B., Joventino, I. R., Ribeiro, S. C., & Cascon, P. (2012). "Necrophiliac behaviour in the "cururu" toad, Rhinella jimi Steuvax, 2002, (Anura, Bufonidae) from Northeastern Brazil" (PDF). North-Western Journal of Zoology. 8 (2): 365.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Lewis, Stephanie (1989). Cane Toads: an Unnatural History. New York: Doubleday.

- Izzo, T. J., Rodrigues, D. J., Menin, M., Lima, A. P., & Magnusson, W. E. (2012). "Functional necrophilia: a profitable anuran reproductive strategy?". Journal of Natural History. 46 (47–48): 2961–2967. doi:10.1080/00222933.2012.724720.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Lazarus, Arnold A. (January 1968). "A case of pseudo-necrophilia treated by behaviour therapy". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 24 (1): 113–115. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(196801)24:1<113::aid-jclp2270240137>3.0.co;2-q. ISSN 0021-9762.

- Molinari, Christina (August 2005). "NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS" (PDF). Florida Gulf Coast University Thesis: 59–60.

- Crafford, J. E. (1990), "The Role of Feral House Mice in Ecosystem Functioning on Marion Island", Antarctic Ecosystems, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 359–364, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-84074-6_40, ISBN 9783642840760

- "CRIMES ACT 1900 – SECT 81C Misconduct with regard to corpses". www6.austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Código Penal (Decreto-Lei nº 2.848)". Presidency of the Republic. 7 December 1940. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Free translation from Brazilian Portuguese to English.

- "The Indian Penal Code (IPC): Dowry Law Misuse (IPC 448) By Indian Women". Mynation.net. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- Butterworths Crimes Act 1961: Wellington: Butterworths: 2003

- "Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act 32 of 2007" (PDF). December 2007. sec. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 May 2012.

- "Fakta: Nekrofili och brott mot griftefrid". HD (in Swedish). Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- Aggrawal 2016, p. 200.

- Aggrawal 2010, pp. 201–210.

- Posner, Richard A.; Silbaugh, Katharine B. (1996). A Guide to America's Sex Laws. University of Chicago Press. pp. 213–216.

- "Texas Penal Code Chapter 42. Disorderly Conduct And Related Offenses". Archived from the original on 28 April 2014.

- Although the wording is somewhat ambiguous, the Supreme Court of Wisconsin determined this statute applied to "sexual contact or sexual intercourse with a victim already dead at the time of the sexual activity when the accused did not cause the death of the victim" in State v. Grunke.

Sources

- Aggrawal, Anil (2010). Necrophilia: Forensic and Medico-legal Aspects. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1420089127.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Aggrawal, Anil (19 April 2016). Necrophilia: Forensic and Medico-legal Aspects. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-8913-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Finbow, Steve (2014). Grave Desire: A Cultural History of Necrophilia. Winchester, UK: Zero Books. ISBN 978-1-7827-9342-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee Mellor (2016) Homicide: A Forensic Psychology Casebook. CRC Press. ISBN 9781498731522.

- Purcell, Catherine; Arrigo, Bruce A. (7 June 2006). The Psychology of Lust Murder: Paraphilia, Sexual Killing, and Serial Homicide. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-046257-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- West, Sarah G.; Resnick, Phillip J. (2017). "Necrophilia". Unusual and Rare Psychological Disorders: A Handbook for Clinical Practice and Research. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-024586-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Lisa Downing, Desiring the Dead: Necrophilia and Nineteenth-Century French Literature. Oxford: Legenda, 2003

- Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Psychopathia Sexualis. New York: Stein & Day, 1965. Originally published in 1886.

In literature

- Gabrielle Wittkop, The Necrophiliac, 1972

- Barbara Gowdy, We So Seldom Look on Love, 1992

- Frank O'Hara, Ode on Necrophilia, 1960