Fall Rot

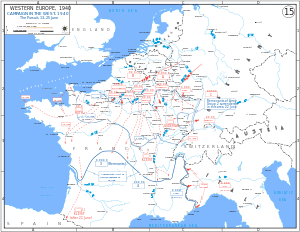

During World War II, Fall Rot (Case Red) was the plan for the second phase of the conquest of France by the German Army and began on 5 June 1940. It had been made possible by the success of Fall Gelb (Case Yellow), the invasion of the Benelux countries and northern France in the Battle of France and the encirclement of the Allied armies in the north on the Channel coast. Powerful forces were also to advance into France.[1]

| Fall Rot | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of France | |

Fall Rot (Case Red) | |

| Location | France |

| Executed by | German army |

| Outcome | German victory |

Fall Rot consisted of two sub-operations, a preliminary attack in the west began on 5 June, over the river Somme in the direction of the Seine and the main offensive by Army Group A started on 9 June in the centre over the river Aisne.[1]

Background

French defensive preparations

By the end of May 1940, the best-equipped French armies had been sent north and lost in Fall Gelb and the evacuation from Dunkirk, which cost the Allies 61 divisions. Weygand was faced with the prospect of defending a 965 km (600 mi) front from Sedan, along the Aisne and Somme rivers to Abbeville on the Channel, with 64 French divisions. The 51st (Highland) Infantry Division and a few British divisions being sent to French ports south of the Somme to form the "2nd BEF" were the only British contribution. Weygand lacked reserves to counter a breakthrough against 142 German divisions and the Luftwaffe, which had air supremacy, except over the English Channel.[2]

Between six and ten million civilian refugees had fled the fighting and clogged the roads, in what became known as L'Éxode (The Exodus) and few arrangements had been made for their reception. The population of Chartres declined from 23,000 to 800 and Lille from 200,000 to 20,000, while cities in the south such as Pau and Bordeaux rapidly grew in size.[3]

Prelude

Battle of Abbeville

The Battle of Abbeville took place from the 28 May to 4 June 1940 near Abbeville during the Battle of France in the Second World War. While Operation Dynamo, the Dunkirk evacuation, was under way, General Maxime Weygand attempted to exploit the immobilisation of German forces to attack northwards over the Somme and rescue the trapped Allied forces in the Dunkirk pocket. The Allied attack was carried out by the French 2e Division cuirassée (2nd DCr, heavy armoured division) and 4e Division cuirassée (4th DCr) and the British 1st Armoured Division. The Allied attacks reduced the size of the German bridgehead by about 50 percent.[4]

Weygand line

The French armies had fallen back on their lines of supply and communications and had easier access to repair shops, supply dumps and stores. About 112,000 evacuated French soldiers were repatriated via the Normandy and the Brittany ports. It was some substitute for the lost divisions in Flanders. The French were also able to make good a significant amount of their armoured losses and raised the 1st and 2nd DCr; the 4th DCr also had its losses replaced; morale rose and was very high by the end of May 1940.[5]

Morale improved because most French soldiers knew of German success only by hearsay; surviving French officers had gained tactical experience against German mobile units and had increased confidence in their weapons, after seeing their artillery (which the post-battle analysis of the Wehrmacht recognised as technically excellent) and tanks perform better in combat than German armour. The French tanks had heavier armour and bigger guns.[6] Between 23 and 28 May, the French reconstituted the Seventh and Tenth armies. Weygand decided on hedgehog tactics, in defence in depth, to inflict maximum attrition on German units. He employed units in towns and small villages, which were prepared for all-round defence. Behind that, the new infantry, armoured and half-mechanised divisions were ready to counter-attack and relieve the surrounded units, which were ordered to hold out at all costs.[7]

Battle

Army Group B attacked either side of Paris; in its 47 divisions it had the majority of the mobile units.[2] After 48 hours, the Germans had not broken through the French defence.[8] On the Aisne, the XVI Panzerkorps (General Erich Hoepner) employed over 1,000 armoured fighting vehicles (AFVs) in two panzer divisions and a motorised division against the French. The assault was crude and Hoepner lost 80 out of 500 AFVs in the first attack. The German 4th Army had captured bridgeheads over the Somme but the Germans struggled to get over the Aisne as the French defence in depth frustrated the crossing.[9] At Amiens, the Germans were repeatedly driven back by powerful French artillery concentrations, a marked improvement in French tactics.[10]

The German Army relied on the Luftwaffe to silence French artillery as the German infantry inched forward, only forcing crossings on the third day.[10] The Armée de l'Air (French Air Force) attempted to bomb them but failed. German sources acknowledged the battle was "hard and costly in lives, the enemy putting up severe resistance, particularly in the woods and tree lines continuing the fight when our troops had pushed past the point of resistance".[11] South of Abbeville, the French Tenth Army (General Robert Altmayer) had its front broken and it was forced to retreat to Rouen and southwards over the Seine river. The 7th Panzer Division headed west over the Seine river through Normandy and captured the port of Cherbourg on 18 June, forcing the surrender of much of the 51st (Highland) Division on 12 June.[12] German spearheads were overextended and vulnerable to counter strokes but the Luftwaffe denied the French the ability to concentrate and the fear of air attack negated their mass and mobile use by Weygand.[13]

On 10 June, the French government declared Paris an open city.[14] The German 18th Army advanced on Paris against determined French opposition but the line was broken in several places. Weygand asserted it would not take long for the French Army to disintegrate. On 13 June, Churchill attended a meeting of the Anglo-French Supreme War Council at Tours. He suggested a Franco-British Union, which the French rejected.[15] On 14 June, Paris fell and the Parisians unable to flee the city found that in most cases the Germans were extremely well mannered.[12][16]

The air superiority established by the Luftwaffe became air supremacy, with the Armée de l'Air on the verge of collapse.[17] The French had only just begun to make the majority of bomber sorties; between 5 and 9 June during Operation Paula, when over 1,815 sorties were flown, 518 by bombers. The number of sorties flown declined as losses became impossible to replace. The RAF attempted to divert the attention of the Luftwaffe with 660 sorties flown against targets over the Dunkirk area but lost many aircraft; on 21 June, 37 Bristol Blenheims were destroyed. After 9 June, French aerial resistance virtually ceased and some surviving aircraft withdrew to French North Africa. Luftwaffe attacks concentrated on the direct and indirect support of the army. The Luftwaffe attacked lines of resistance which then quickly collapsed under armoured attack.[18]

Maginot line

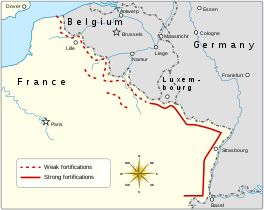

Army Group C in the east was to help Army Group A to encircle and capture the French forces on the Maginot line. The goal of the operation was to envelop the Metz region, with its fortifications, to prevent a French counter-offensive from Alsace against the German line on the Somme. The XIX Panzerkorps (General Heinz Guderian) was to advance to the French border with Switzerland and trap the French forces in the Vosges Mountains while the XVI Panzerkorps attacked the Maginot Line from the west, into its vulnerable rear to take the cities of Verdun, Toul and Metz. The French had moved the 2nd Army Group from the Alsace and Lorraine to the Weygand line on the Somme, leaving only small forces guarding the Maginot line. After Army Group B had begun its offensive against Paris and into Normandy, Army Group A began its advance into the rear of the Maginot line. On 15 June, Army Group C launched Operation Tiger, a frontal assault across the Rhine into France.[19]

German attempts to break the Maginot line prior to Tiger had failed. One assault lasted for eight hours at the north end of the line, costing the Germans 46 dead and 251 wounded for two French were killed at Ouvrage Ferme Chappy (Chappy Farm shelter) and one at Ouvrage Fermont. On 15 June, the last well-equipped French forces, including the Fourth Army, were preparing to leave as the Germans struck; only a skeleton force held the line. The Germans greatly outnumbered the French and could call upon I Armeekorps of seven divisions and 1,000 guns, although most were First World War vintage and could not penetrate the thick armour of the fortresses. Only 88 mm guns were effective and 16 were allocated to the operation; 150 mm guns and eight railway batteries were also employed. The Luftwaffe deployed Fliegerkorps V.[20]

The battle was difficult and slow progress was made against strong French resistance but the fortresses were overcome one by one.[21] Ouvrage Schoenenbourg fired 15,802 75 mm rounds at German infantry. It was the most bombarded of all the French positions but its armour protected it from fatal damage. The same day that Tiger began, Unternehmen Kleiner Bär started. Five assault divisions of the VII Armeekorps crossed the Rhine into the Colmar area with a view to advancing to the Vosges Mountains. It had 400 artillery pieces including heavy artillery and mortars. The French 104th Division and 105th Division were driven back into the Vosges Mountains on 17 June. On the same day, XIX Korps reached the Swiss border and the Maginot defences were cut off from France. Most units surrendered on 25 June and the Germans claimed to have taken 500,000 prisoners. Some main fortresses continued the fight, despite appeals for surrender. The last fort did not surrender until 10 July and then only under protest and after a request from General Alphonse Georges. Of the 58 big fortifications on the Maginot Line, ten were captured by the German army.[22]

Aftermath

Second BEF evacuation

The evacuation of the second BEF took place during Operation Aerial between 15 and 25 June. The Luftwaffe, with complete domination of the French skies, was determined to prevent more Allied evacuations after the Dunkirk debacle. Fliegerkorps I was assigned to the Normandy and Brittany sectors. On 9 and 10 June, the port of Cherbourg was subject to 15 tonnes of German bombs, while Le Havre received 10 bombing attacks that sank 2,949 GRT of escaping Allied shipping. On 17 June, Junkers Ju 88s (mainly from Kampfgeschwader 30) sank a "10,000 tonne ship" which was the 16,243 GRT liner RMS Lancastria off St Nazaire, killing some 4,000 Allied personnel (nearly doubling the British killed in the Battle of France), yet the Luftwaffe failed to prevent the evacuation of some 190,000–200,000 Allied personnel.[23]

Armistice

Discouraged by the hostile reaction in the cabinet to a British proposal for a Franco-British Union and believing his ministers no longer supported him, Prime Minister Paul Reynaud resigned on 16 June. He was succeeded by Marshal Philippe Pétain, who delivered a radio address to the French people, announcing his intention to ask for an armistice with Germany. When Hitler received word from the French government that they wished to negotiate an armistice, he selected the Forest of Compiègne, the site of the 1918 Armistice, as the venue.[24] On 21 June 1940, Hitler visited the site to start the negotiations, which took place in the railway carriage in which the 1918 Armistice was signed.[25] After listening to the preamble, Hitler left the carriage in a calculated gesture of disdain for the French delegates and negotiations were turned over to Wilhelm Keitel, the Chief of Staff of Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW). The armistice was signed on the next day at 6:36 p.m. (French time), by General Keitel for Germany and General Charles Huntziger for France and came into effect at 12:35 a.m. on 25 June, once the Franco-Italian Armistice had been signed, at 6:35 p.m. on 24 June, near Rome.[26]

Italy

Italy declared war on France and Britain on the evening of 10 June, to take effect just after midnight. The two sides exchanged air raids on the first day of war but little transpired on the Alpine front, since both France and Italy had adopted a defensive strategy. There was some skirmishing between patrols and the French forts of the Ligne Alpine exchanged fire with their Italian counterparts of the Vallo Alpino. On 17 June, France announced that it would seek an armistice with Germany and on 21 June, with a Franco-German armistice about to be signed, the Italians launched a general offensive all along the Alpine front, with the main attack in the northern sector and a secondary advance along the coast.[26] The offensive was conducted by 32 Italian divisions and penetrated a few kilometres into French territory, against the Army of the Alps (General René Olry) which held the frontier with three divisions. The coastal town of Menton was captured but on the Côte d'Azur the invasion was held up by a French NCO and seven men.[27] On the evening of 24 June, a Franco-Italian Armistice was signed at Rome and came into effect at the same time as the Second Armistice at Compiègne with Germany (22 June), just after midnight on 25 June.[26]

Footnotes

- Frieser 2005, p. 315.

- Healy 2008, p. 84.

- Jackson 2001, pp. 119–120.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 259–271.

- Alexander 2007, pp. 225–226.

- Alexander 2007, p. 227.

- Alexander 2007, pp. 231, 238.

- Alexander 2007, p. 248.

- Alexander 2007, p. 245; Maier et al. 1991, p. 297.

- Alexander 2007, p. 249.

- Alexander 2007, p. 250.

- Healy 2008, p. 85.

- Alexander 2007, p. 240.

- Shirer 1990, p. 738.

- Maier et al. 1991, pp. 300–301.

- Shirer 1941.

- Hooton 2008, p. 86.

- Hooton 2008, pp. 84–85.

- Romanych & Rupp 2010, p. 52.

- Romanych & Rupp 2010, p. 56.

- Romanych & Rupp 2010, pp. 56–80.

- Romanych & Rupp 2010, pp. 90–91.

- Hooton 2008, p. 88.

- Evans 2000, p. 156.

- Dear & Foot 2001, p. 326.

- Frieser 2005, p. 317.

- Horne 1982, p. 631.

References

Books

- Dear, I.; Foot, M. (2001). The Oxford Companion to World War II. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860446-4.

- Ellis, Major L. F. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1954]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The War in France and Flanders 1939–1940. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-056-6. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Evans, Martin Marix (2000). The Fall of France: Act of Daring. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-85532-969-0.

- Frieser, K-H. (2005). The Blitzkrieg Legend (English trans. ed.). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-294-2.

- Guderian, H. (1976) [1952]. Panzer Leader (Futura repr. ed.). London: Michael Joseph. ISBN 978-0-86007-088-7.

- Healy, M.; Prigent, J., eds. (2008). Panzerwaffe: The Campaigns in the West 1940. I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-3240-8.

- Hooton, E. R. (2008) [1994]. Phoenix Triumphant: The Rise and Rise of the Luftwaffe. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 978-1-86019-964-6.

- Horne, A. (1982) [1969]. To Lose a Battle: France 1940 (Penguin repr. ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-14-005042-4.

- Jackson, Julian (2001). France: The Dark Years, 1940–1944. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820706-1.

- Maier, K.; Rohde, H.; Stegemann, B.; Umbreit, H. (1991). Die Errichtung der Hegemonie auf dem europäischen Kontinent [Germany's Initial Conquests in Europe]. Germany and the Second World War. II (English trans. ed.). London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822885-1.

- Romanych, M.; Rupp, M. (2010). Maginot Line 1940: Battles on the French Frontier. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-499-2.

- Shirer, William L. (1941). Berlin Diary: The Journal of a Foreign Correspondent, 1934–1941. Simon & Schuster. OCLC 366845.

- Shirer, William L. (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-671-72868-7.

Journals

- Alexander, M. S. (April 2007). "After Dunkirk: The French Army's Performance Against Case Red, 25 May to 25 June 1940". War in History. 14 (2): 219–264. doi:10.1177/0968344507075873. ISSN 0968-3445.

Further reading

- Benoist-Méchin, J. (1956). Soixante jours qui ébranlèrent l'occident: 10 mai – 10 juillet 1940 [Sixty Days that Shook the West: The Fall of France 1940] (in French). Paris: A. Michel. OCLC 836238123.

- Forczyk, R. (2019) [2017]. Case Red: The Collapse of France (pbk. Osprey ed.). Oxford: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4728-2446-2.

- Prételat, A–G. (1950). Le Destin Tragique de la Ligne Maginot [The Tragic Destiny of the Maginot Line]. La Seconde Guerre mondiale, histoire et souvenirs (in French). Paris: Berger-Levrault. OCLC 12905841.

- Rodolfe, R. (1949). Combats dans la Ligne Maginot [Operations on the Maginot Line] (in French). Paris: Ponsot. OCLC 12905932.

- Rowe, V. (1959). The Great Wall of France: The Triumph of the Maginot Line (1st ed.). London: Putnam. OCLC 773604722.

- Wright, D. P., ed. (2013). 16 Cases of Mission Command (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combined Studies Institute Press US Army Combined Arms Center. ISBN 978-0-9891372-1-8. Retrieved 5 September 2015.