RMS Lancastria

RMS Lancastria was a British ocean liner requisitioned by the UK Government during the Second World War. She was sunk on 17 June 1940 during Operation Ariel. Having received an emergency order to evacuate British nationals and troops in excess of its capacity of 1,300 passengers,[2] modern estimates range between 3,000 and 5,800 fatalities—the largest single-ship loss of life in British maritime history.[3][4]

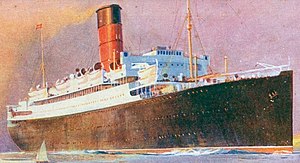

A postcard of RMS Lancastria from 1927 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: |

|

| Namesake: |

|

| Owner: | Cunard Line |

| Builder: | William Beardmore and Company |

| Launched: | 31 May 1920 |

| Maiden voyage: | 19 June 1922 |

| Out of service: | 17 June 1940 |

| Nickname(s): |

|

| Fate: | Sunk by air attack on 17 June 1940 off St. Nazaire |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage: | 16,243 GRT |

| Length: | 578 ft (176 m) |

| Beam: | 70 ft (21 m) |

| Height: | 43 ft (13 m) |

| Draught: | 31.4 ft (9.6 m) |

| Decks: | 7 decks and a shelter deck |

| Installed power: | 6 steam turbines, 2,500 nhp |

| Propulsion: | twin screw |

| Speed: | 16.5 knots (31 km/h; 19 mph) |

| Capacity: |

|

| Crew: | 300 |

Career

The ship was launched in 1920 as Tyrrhenia by William Beardmore and Company of Dalmuir on the River Clyde for Anchor Line, a subsidiary of Cunard. She was the sister ship of RMS Cameronia that Beardmore's had built for the same customer the previous year.[5] Tyrrhenia was 16,243 gross register tons, 578 feet (176 m) long and could carry 2,200 passengers in three classes. She made her maiden voyage, Glasgow–Quebec City–Montreal, on 19 June 1922.[6]

In 1924 she was refitted for two classes and renamed Lancastria, after passengers complained that they could not properly pronounce Tyrrhenia. She sailed scheduled routes between Liverpool and New York until 1932, and was then used as a cruise ship in the Mediterranean Sea and Northern Europe.[7] On 10 October 1932 Lancastria rescued the crew of the Belgian cargo ship SS Scheldestad, which had been abandoned in a sinking condition in the Bay of Biscay.[8] In 1934 the Catholic Boy Scouts of Ireland chartered Lancastria for a pilgrimage to Rome.[7][9] At the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, Lancastria was in the Bahamas. She was ordered to sail from Nassau to New York for refitting as she had been requisitioned as a troopship, becoming HMT Lancastria. Unnecessary fittings were removed, she was repainted in battleship grey, the portholes were blacked out, and a 4-inch gun was installed. She was first used to ferry men and supplies between Canada and the United Kingdom. In April 1940, she was one of twenty troopships in Operation Alphabet, the evacuation of troops from Norway, and was bombed on the return journey although she escaped damage. Shortly afterwards, Lancastria carried troops to consolidate the invasion of Iceland. Returning to Glasgow, the captain requested that surplus oil in her tanks be removed, but there was insufficient time before she was ordered to Liverpool for a refit. Crew members were either discharged or sent on leave.[10]

Loss

Lancastria was sunk on 17 June 1940 off the French port of St. Nazaire while taking part in Operation Ariel, the evacuation of British nationals and troops from France, two weeks after the Dunkirk evacuation.

Outward voyage

Within hours of berthing at Liverpool, Lancastria was urgently recalled to sea; loud-speaker announcements at the main railway station successfully recalled nearly all the crew members;[11] she arrived in Plymouth on 15 June to await orders. She was originally sent to Quiberon Bay as part of Operation Arial (or Ariel), which was the evacuation of the remainder of the British Expeditionary Force which had been cut-off to the south of the German advance through France, amounting to some 124,000 men, mostly logistic support troops, from various ports in western France. Accompanying Lancastria was the 20,341-ton liner, Franconia. Finding that she was not required for the evacuation from Lorient, the captain of Lancastria, Rudolph Sharp, was sent on towards the port of St. Nazaire, where many more troops were waiting to be lifted, On the way, an air raid damaged Franconia which returned to England for repairs, leaving Lancastria to continue alone. She arrived in the mouth of the Loire estuary late on 16 June. Because the port has to be accessed along a tidal channel, Lancastria anchored in the Charpentier Roads, some 5 miles (8.0 km) south-west of St. Nazaire, at 04:00 on 17 June,[12] along with some thirty other merchant vessels of all sizes.[13]

Embarkation

Early in the morning, three RNVR officers came aboard to ask how many troops Lancastria could take. Her normal complement in troopship configuration was 2,180 including 330 crew; however, Captain Sharp had brought 2,653 men back from Norway, so he replied that he could take 3,000 "at a pinch". He was told that he should take as many as he possibly could "without regard to the limits of International Law".[12] Troops were ferried out to Lancastria and the other larger ships by destroyers, tugs, fishing boats and other small craft,[13] a round trip of three or four hours, sometimes being machine-gunned by German aircraft, although apparently without casualties.[14] By the mid-afternoon of 17 June she had embarked an unknown number (estimates range from 4,000 up to 9,000)[4] line-of-communication troops (including Pioneer and Royal Army Service Corps soldiers) and Royal Air Force personnel, together with about forty civilian refugees, including embassy staff and employees of Fairey Aviation of Belgium with their families.[15] People were crowded into whatever spaces were available including the large cargo holds. One Royal Engineers officer reported that he had been told by one of Lancastria's loading officers that over 7,200 people had come aboard. Captain Sharp estimated the number to be 5,500.[16]

At 13:50, during an air-raid, the nearby Oronsay, a 20,000-ton Orient Liner, was hit on the bridge by a German bomb. Lancastria was free to depart and the captain of the British destroyer HMS Havelock advised her to do so; but, without a destroyer escort as defence against possible submarine attack, Sharp decided to wait for Oronsay before leaving.[17]

Sinking

A fresh air raid began at 15:50 by Junkers Ju 88 bomber aircraft from Kampfgeschwader 30. Lancastria was hit by three or possibly four bombs. A number of survivors reported that one bomb had gone down the ship's single funnel which is most likely, given the speed with which the ship sank – about 15–20 minutes. The testimony of an engineering officer, Frank Brogden, who was in the engine room at the time contradicts this. Brogden's account states that one bomb landed close to the funnel and entered No. 4 hold. Two other bombs landed in No. 2 and No. 3 holds while a fourth landed close to the port side of the ship, rupturing the fuel oil tanks, though even with this damage, the ship should have stayed afloat for longer, unless the report of the bomb in the funnel was true.[18] As the ship began to list to starboard, orders were given for the men on deck to move to the port side in an effort to counteract it, but this caused a list to port which could not be corrected.[19] The ship was equipped with sixteen lifeboats and 2,500 life jackets;[14] but many of the boats could not be launched because they had been damaged in the bombing or because of the angle of the hull. The first boat away was filled with women and children but it capsized on landing in the water and a second had to be lowered for them. A third boat had its bottom stove in by landing too fast. A large number of men who jumped over the side were killed by hitting the side of the hull or had their necks broken by their life jackets on impact with the water.[20] As Lancastria began to capsize, some of those who were still on board managed to scramble onto the ship's underside. According to some accounts, these were heard to be singing 'Roll Out the Barrel' and 'There'll Always Be an England', though some survivors strongly deny this.[18] The ship sank at 16:12, within twenty minutes of being hit,[21] which gave little time for other vessels to respond. Many of those in the water drowned because there were insufficient life jackets, or died from hypothermia, or were choked by fuel oil.[22] According the Jonathan Fenby novel "The Sinking of the Lancastria" the German aircraft straffed survivors in the water.[23]

Survivors were taken aboard other British and US evacuation vessels, the trawler HMT Cambridgeshire rescuing 900.[24] Capt WG Euston recommended several of his crew for awards, including Stanley Kingett for "making repeated journeys in a lifeboat to pick up exhausted men from the water while under machine-gun fire from enemy planes", and William Perrin for "keeping up continuous machine-gun fire in an attempt to prevent enemy planes machine-gunning men in the water."[25] There were 2,477 survivors, of whom about 100 were still alive in 2011.[4] Many families of the dead knew only that they died with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF); the death toll accounted for roughly a third of the total losses of the BEF in France.[4] She sank around 5 nmi (9.3 km) south of Chémoulin Point in the Charpentier roads, around 9 nmi (17 km) from St. Nazaire. Lancastria Association names 1,738 people known to have been killed.[26] In 2005, Fenby wrote that estimates of the death toll vary from fewer than 3,000 to 5,800 people although it is also estimated that as many as 6,500 people perished, the largest loss of life in British maritime history.[3]

Rudolph Sharp survived the sinking and went on to command the RMS Laconia, losing his life on 12 September 1942 in the Laconia incident off West Africa.[27]

Availability of information

The immense loss of life was such that the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, immediately suppressed news of the disaster through the D-Notice system,[28] telling his staff that "The newspapers have got quite enough disaster for today at least". In his memoirs, Churchill stated that he had intended to release the news a few days later, but that events in France "crowded upon us so black and so quickly that I forgot to lift the ban".[29]

The sinking was announced that evening during the English-language Nazi propaganda radio programme, Germany Calling by its presenter William Joyce, better known as "Lord Haw-Haw"; however his claims were notoriously unreliable and had little public credence.[30] The story was finally broken in the United States by the Press Association on 25 July,[31] in The New York Times, and the next day in Britain by The Scotsman, more than five weeks after the sinking. Other British newspapers then covered the story, including the Daily Herald (also on 26 July), which carried the story on its front page, and Sunday Express on 4 August; the latter included a photograph of the capsized ship with her upturned hull lined with men under the headline "Last Moments of the Greatest Sea Tragedy of All Time".[4] All the photographs of the sinking were taken by Frank Clements, a volunteer storeman aboard HMS Highlander, who was exempt from the regulations prohibiting the use of cameras by service personnel.[28]

However, there were earlier reports of the sinking and the scale of the disaster from survivors in local British newspapers. Mr H J Cooper is quoted in the Chelmsford Chronicle on 28 June: "I am afraid thousands died, but tell the world they sang 'Roll out the Barrel' as they died."[32] Private Ronald Herbert Yorke (Sherwood Foresters) is quoted in the Ripley and Heanor News on 5 July: "Hundreds of my pals were imprisoned below. They had no chance, because the ship went down in 15 minutes. Those who got away were machine gunned in the water".[33]

In July 2007 another request for documents held by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) related to the sinking was rejected by the British government. Lancastria Association of Scotland made a further request in 2009. They were told that release under the FOIA would not be given because of several exemptions.[34][lower-alpha 1] In the face of continued campaigning by relatives, the MoD stated in 2015 that all known documents had long since been released through the National Archives.[35] On 17 June 2010 (70th anniversary of the sinking) Janet Dempsey gave a lecture at The National Archives entitled "Forgotten Tragedy: The Loss of HMT Lancastria". This drew on all known information held at Kew. A transcript and podcast are available from The National Archives website.

Wreck status

The British government has not made the site a war grave under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986, stating that it has no jurisdiction over French territorial waters.[36] Early in the 21st century the French Government placed an exclusion zone around the wreck site.

The Lancastria Association of Scotland began a campaign in 2005 to secure greater recognition for the loss of life aboard Lancastria and the acknowledgment of the endurance of survivors that day. It petitioned Government of the United Kingdom to have the wreck site designated an official maritime war grave. The British Government did not do so as it was within French territorial waters, outside the jurisdiction of the Act.[37] The campaign received support from all parties, but the MoD said that such a move would be "purely symbolic" and have no effect. In 2006, 14 additional wrecks sunk at the Battle of Jutland were designated as war graves, but Lancastria was not.

The MoD stated in 2015 that "as the French Government has provided an appropriate level of protection to Lancastria through French law and it is formally considered a military maritime grave by the MoD, we believe that the wreck has the formal status and protection it deserves."[35]

Legacy

All service personnel killed during the Second World War are recorded by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, and where known that they lost their lives on Lancastria; 1,816 burials are recorded, over 400 of them in France.[38]

The missing British military dead from the sinking of Lancastria (those whose bodies were not recovered or were unable to be identified) are commemorated on a number of Commonwealth War Graves Commission memorials (those identified were buried in cemeteries and are marked with Commission headstones). Around 700 missing of the British Expeditionary Force are commemorated on the Dunkirk Memorial. The missing dead who served in the Navy are commemorated on the naval memorials at Chatham, Plymouth and Portsmouth, with missing merchant seamen named at the Tower Hill Memorial, and the missing airmen who went down with the ship, listed on the Runnymede Memorial.[39][40]

After the war, Lancastria Survivors Association was founded by Major Peter Petit, but this lapsed on his death in 1969. It reformed in 1981 as The HMT Lancastria Association and continues the tradition of a parade and remembrance service at the Church of St Katharine Cree in the City of London, where there is a memorial stained glass window.[41] The Lancastria Association of Scotland was formed in 2005 and holds its annual service at St George's West Church in Edinburgh.[42]

The Lancastria Association of Scotland has members throughout the UK, France and the rest of Europe as well as members in North America, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. It also organises the largest memorial service for the victims in the UK. The service, which is attended by survivors and relatives of both victims and survivors together with representatives of the French and Scottish Governments and a number of veterans organisations and is held on the Saturday closest to the anniversary of 17 June each year at St. George's West Church, Edinburgh.

In June 2010 to mark the 70th anniversary of the sinking, special ceremonies and services of remembrance were held in Edinburgh and St. Nazaire. As the 100th anniversary of the RMS Titanic sinking took place in 2012, fresh calls were made for "official recognition" of the loss of Lancastria by the British Government.[43] The day of the 75th anniversary of the loss of Lancastria was marked in the Westminster Parliament on 17 June 2015 at Prime Minister's Questions by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, who was standing in for the Prime Minister. Osborne said of the sinking; "It was kept secret at the time for reasons of wartime secrecy, but I think it is appropriate today in this House of Commons to remember all those who died, those who survived, and those who mourn them."[44]

In June 2008, the first batch of commemorative medals were presented to survivors and relatives of victims and survivors; the HMT Lancastria Commemorative Medal, which represented "official Scottish Government recognition" of the Lancastria disaster.[45] The medal was designed by Mark Hirst, grandson of Lancastria survivor Walter Hirst.[46] The inscription on the rear of the medal reads: "In recognition of the ultimate sacrifice of the 4000 victims of Britain's worst ever maritime disaster and the endurance of survivors – We will remember them".[45] The front of the medal depicts Lancastria with the text "HMT Lancastria – 17th June 1940". The medal ribbon has a grey background with a red and black central stripe, representative of the ship's wartime and merchant marine colours.

.jpg)

A memorial on the sea-front at St Nazaire was unveiled on 17 June 1988, "in proud memory of more than 4,000 who died and in commemoration of the people of Saint Nazaire and surrounding districts who saved many lives, tended wounded and gave a Christian burial to victims".[42]

Lancastria is represented at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire by a sessile oak tree and a plaque.[47] St Katharine Cree church in the City of London has a memorial window to Lancastria. It also has a model of the ship in a glass case and the ship's bell is also in the church.[48] Scouting Ireland's national campsite Larch Hill has an anchor memorial to Lancastria, commemorating the legacy of the Catholic Boy Scouts of Ireland's pilgrimage in 1932.[49]

In October 2011, the Lancastria Association of Scotland has erected a memorial to the victims on the site where the ship was built, the former Dalmuir shipyard at Clydebank, Glasgow, now the grounds of the Golden Jubilee Hospital.[46] In September 2013, a plaque was unveiled at Liverpool's Pier Head by Lord Mayor Gary Millar commemorating the loss of the ship.[50][51] The site of Lancastria's wreck lies in French territorial waters and is therefore ineligible for protection under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986; however, at the request of the British Government, in 2006 the French authorities gave the site legal protection as a war grave.[52]

References

Notes

- Section 36; prejudice to the effective conduct of public affairs; Section 40(2); contains personal information; Section 40(3); Release would contravene section 10 of the Data Protection Act 1998: "processing likely to cause damage or distress"; Section 41; supplied in confidence; Section 44; Exempt from disclosure under the Human Rights Act 1998.

Citations

- Talbot-Booth, EC (1937). Merchant Ships. London: Sampson-Low and Marston.

- "Lancastria Association of Scotland". Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- Fenby 2005, p. 247.

- "BBC – History – World Wars: The 'Lancastria' – a Secret Sacrifice in World War Two".

- "Lancastria". Chris's Cunard Page. Archived from the original on 12 August 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- "Lancastria". Greatships.net. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- "About Us : History of Scouting in Ireland". Scouting Ireland. 2009. Archived from the original on 6 November 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- "Belgian Merchant P–Z" (PDF). Belgische Koopvaardij. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/letters/scouts-trip-to-rome-1934-1.1147797

- Fenby 2005, pp. 9–11.

- Fenby 2005, p. 12.

- Tackle 2009, p. 132.

- Fenby 2005, p. 103.

- Fenby 2005, p. 112.

- Sebag-Montiefiore 2006, p. 487.

- Tackle 2009, pp. 132–133.

- Sebag-Montiefiore 2006, pp. 489.

- Tackle 2009, p. 134.

- Fenby 2005, pp. 141–142.

- Sebag-Montiefiore 2006, pp. 492–493.

- Fenby 2005, p. 163.

- Tackle 2009, p. 135.

- Fenby 2005, pp. 164–165.

- Sebag-Montiefiore 2006, p. 495.

- Bowler, Pete (17 June 2000). "Survivors mark forgotten disaster". The Guardian.

- "Victim list". Lancastria.org.uk. 17 June 1940. Retrieved 3 June 2015. List of those found and buried ashore, or reported to be on board at the time of the sinking and presumed lost in the action

- "Rudolph Sharp (British) – Crew lists of Ships hit by U-boats". uboat.net. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- Tackle 2009, p. 136.

- Churchill 1949, p. 172.

- Fenby 2005, p. 206.

- "LANCASTRIA SUNK, SAYS U.S.". Hull Daily Mail. 25 July 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "They Sang As They Died". Chelmsford Chronicle (9172). 28 June 1940. p. 3. Retrieved 5 March 2019 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "More Ripley Lads Back Home – How a Ripley Private Escaped". Ripley and Heanor News (2675). 5 July 1940. p. 3. Retrieved 5 March 2019 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Martyred Ships: Cold Cases. Maritime Mysteries. Grand Angle Productions. 2012. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014.

- Fraser, Graham (13 June 2015). "Lancastria: The forgotten tragedy of World War Two". BBC Scotland. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- "War grave campaign in legal move". BBC News website. BBC. 25 June 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- "War grave campaign in legal move". BBC News website. BBC. 20 November 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- Fenby 2005, p. 234.

- "The Sinking of HMT Lancastria". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- According to CWGC Records of identified Burials in France as of 17 June 1940 of "Lancastria" total 1486 (British Army 1449; RAF 33 CWGC Record Merchant Navy 4CWGC record

- "About us". Archived from the original on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- "The Lancastria Association of Scotland". Lancastria Organization website. Archived from the original on 26 August 2009.

- "Recognition remains sunk without a trace, by Mark Hirst". The Scotsman. 19 April 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- https://www.maritimeviews.co.uk/focus-on-falmouth/operation-ariel-and-falmouth/

- "Lancastria dead gain recognition". BBC online. 12 June 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "Victims of HMT Lancastria sinking honoured with memorial". The Telegraph. 1 October 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- The National Memorial Arboretum

- "HMT. Lancastria 17th June 1940 & Operation Aerial".

- "NMC Lay a wreath at the Memorial for The Lancastria" (PDF). Scouting Ireland – InSIde Out. July 2012. p. 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2016.

- "Page Not Found". Archived from the original on 3 October 2013.

- Lancastria Victims Remembered Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Howe, Earl, The Right Honorable (17 June 2015). "The 75th anniversary of the sinking of HMT Lancastria". www.gov.uk. Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

Bibliography

- Churchill, Winston S. (1949). The Second World War: Their Finest Hour (Volume II). London: Cassell & Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crabb, Brian James (2002). The Forgotten Tragedy: The Story of the Loss of HMT Lancastria. Donington: Shaun Tyas. ISBN 1-900289-50-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fenby, Jonathan (2005). The Sinking of the "Lancastria": Britain's Greatest Maritime Disaster and Churchill's Cover-up. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-5930-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sebag-Montiefiore, Hugh (2006). "The Sinking of the Lancastria". Dunkirk: Fight to the Last Man. London: Viking Press. pp. 487–495. ISBN 0670910821.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tackle, Patrick (2009). The British Army in France After Dunkirk. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-84415-852-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Sheridan, Robert N. (1989). "Question 23/87". Warship International. XXVI (3): 311. ISSN 0043-0374.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lancastria (ship, 1922). |

- LancastriaArchive.org.uk

- Works about RMS Lancastria at WorldCat Identities