Member of the European Parliament

A Member of the European Parliament (MEP) is a person who has been elected to serve as a popular representative in the European Parliament.[1]

When the European Parliament (then known as the Common Assembly of the ECSC) first met in 1952, its members were directly appointed by the governments of member states from among those already sitting in their own national parliaments. Since 1979, however, MEPs have been elected by direct universal suffrage. Earlier European organizations that were a precursor to the European union did not have MEPs. Each member state establishes its own method for electing MEPs – and in some states this has changed over time – but the system chosen must be a form of proportional representation. Some member states elect their MEPs to represent a single national constituency; other states apportion seats to sub-national regions for election.

Election

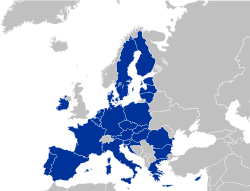

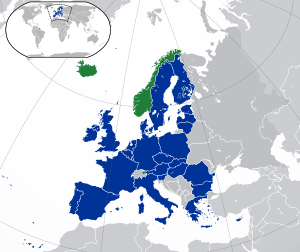

From 1 January 2007, when Romania and Bulgaria joined the EU, there were 785 MEPs, but their number was reduced to 736 at the elections in 2009. With effect from the elections held in May 2014 the number has risen again and now stands nominally at 751, with each member state having at least six and at most 96 MEPs.[2]

Elections are held once every five years, on the basis of universal suffrage. There is no uniform voting system for the election of MEPs; rather, each member state is free to choose its own system, subject to three restrictions:

- The system must be a form of proportional representation, under either the party list or Single Transferable Vote system.

- The electoral area may be subdivided if this will not generally affect the proportional nature of the voting system.

- Any election threshold on the national level must not exceed five percent.

The allocation of seats to each member state is based on the principle of degressive proportionality, so that, while the size of the population of each nation is taken into account, smaller states elect more MEPs than would be strictly justified by their populations alone. As the number of MEPs granted to each member state has arisen from treaty negotiations, there is no precise formula for the apportionment of seats. No change in this configuration can occur without the unanimous consent of all national governments.

Length of service

The European Parliament has a high turnover of members compared to some national parliaments. For instance, after the 2004 elections, the majority of elected members had not been members in the prior parliamentary session, though that could largely be put down to the recent enlargement. Hans-Gert Pöttering served the longest continuous term from the first elections in 1979 until 2014.

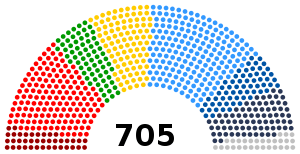

MEPs within the Parliament

MEPs are organised into seven different cross-nationality political groups, except the 57 non-attached members known as Non-Inscrits. The two largest groups are the European People's Party (EPP) and the Socialists & Democrats (S&D). These two groups have dominated the Parliament for much of its life, continuously holding between 40 and 70 percent of the seats together. No single group has ever held a majority in Parliament.[3] As a result of being broad alliances of national parties, European groups parties are very decentralised and hence have more in common with parties in federal states like Germany or the United States than unitary states like the majority of the EU states.[4] Although, the European groups, between 2004 and 2009, were actually more cohesive than their US counterparts.[5][6]

Aside from working through their groups, individual members are also guaranteed a number of individual powers and rights within the Parliament:

- the right to table a motion for resolution

- the right to put questions to the Council of the European Union, the Commission, and to the leaders of the Parliament

- the right to table an amendment to any text in committee

- the right to make explanations of vote

- the right to raise points of order

- the right to move the inadmissibility of a matter

The job of an MEP

Every month except August the Parliament meets in Strasbourg for a four-day plenary session. Six times a year the Parliament meets for two days each in Brussels,[7] where the Parliament's committees, political groups, and other organs also mainly meet.[8] The obligation to spend one week a month in Strasbourg was imposed on Parliament by the Member State governments at the 1992 Edinburgh summit.[9]

Payment and privileges

The total cost of the European Parliament is approximately €1.756 billion euros per year according to its 2014 budget, about €2.3 million per member of parliament.[10] As this cost is shared by over 500 million citizens of 27 countries, the cost per taxpayer is considerably smaller than that of national parliaments.

Salary

Until 2009, MEPs were paid (by their own Member State) exactly the same salary as a member of the lower House of their own national parliament. As a result, there was a wide range of salaries in the European Parliament. In 2002, Italian MEPs earned €130,000, while Spanish MEPs earned less than a quarter of that at €32,000.[11]

However, in July 2005, the Council agreed to a single statute for all MEPs, following a proposal by the Parliament. Thus, since the 2009 elections, all MEPs receive a basic yearly salary of 38.5% of a European Court judge's salary – being around €84,000.[12] This represented a pay-cut for MEPs from some member states (e.g. Italy, Germany, and Austria), a rise for others (particularly the low-paid eastern European Members) and status quo for those from the United Kingdom, until January 2020 (depending on the euro-pound exchange rate). The much-criticised expenses arrangements were also partially reformed.[13]

Financial interests

Members declare their financial interests in order to prevent any conflicts of interest. These declarations are published annually in a register and are available on the Internet.[14]

Immunities

Under the protocol on the privileges and immunities of the European Union, MEPs in their home state receive the same immunities as their own national parliamentarians. In other member states, MEPs are immune from detention and from legal proceedings, except when caught in the act of committing an offence. This immunity may be waived by application to the European Parliament by the authorities of the member state in question.

Individual members

Members' experience

Around a third of MEPs have previously held national parliamentary mandates, and over 10% have ministerial experience at a national level. There are usually a number of former prime ministers and former members of the European Commission. Many other MEPs have held office at a regional or local level in their home states.

Current MEPs also include former judges, trade union leaders, media personalities, actors, soldiers, singers, athletes, and political activists.

Many outgoing MEPs move into other political office. Several presidents, prime ministers or deputy prime ministers of member states are former MEPs, including former President of France Nicolas Sarkozy, former Deputy PM of the United Kingdom Nick Clegg, former Prime Minister of Italy Silvio Berlusconi, Danish former Prime Minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt, and Belgian former PM Elio Di Rupo.

Dual mandates

The so-called "dual mandate", in which an individual is a member of both his or her national parliament and the European Parliament, was officially discouraged by a growing number of political parties and Member States, and is prohibited as of 2009. In the 2004–2009 Parliament, a small number of members still held a dual mandate. Notably, Ian Paisley and John Hume once held "triple mandates" as MEP, MP in the House of Commons, and MLA in the Northern Ireland Assembly simultaneously.

Gender

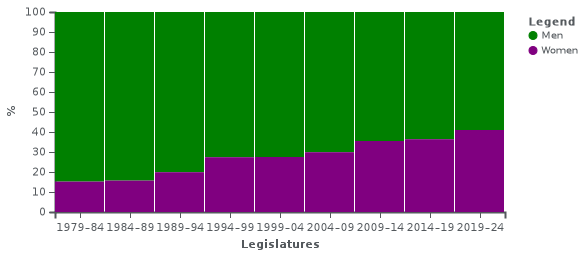

Women are generally under-represented in politics and public life in the EU, as well as in national parliaments, governments and local assemblies.[15] The percentage of women in the EU parliament has increased from 15.2 percent after the first European Parliament election in 1979 to 41 percent after 2019 European Parliament election. To reach gender parity, women should hold 50% of seats and positions of power. However, according to the goal set by the European Institute for Gender Equality, a ratio between 40 and 60 percent is considered acceptable.[17]

After the 2014 European Parliament election 11 countries of 28 reached this goal in their own quota of elected candidates. While in nine EU countries there were mechanisms in place to facilitate female representation, only in four of these countries did women exceeded 40% of elected candidates. On the other hand, in eight countries this goal was reached despite the absence of such systems.[17] The FEMM Committee requested a study exploring the results of the election in terms of gender balance.[18] EU institutions have focused on how to achieve a better gender balance (at least 40 percent) or gender parity (50 percent) in the next Parliament, and for other high-level posts in other institutions.[19]

In the 2019 elections 308 female MEPs were elected (41%). Sweden elected the highest percentage of female MEPs: 55 percent. Overall, thirteen countries elected 45 to 55 percent female MEPs, with seven countries reaching exactly 50 percent. On the other hand, Cyprus has elected zero women, and Slovakia elected only 15 percent. Other Eastern European countries, namely Romania, Greece, Lithuania and Bulgaria, all elected fewer than 30 percent female MEPs. Eight member states elected a lower number of women in 2019 than in 2014. Malta, Cyprus and Estonia lost the most female representation in the EU parliament, dropping by 17 percentage points, while Slovakia dropped by 16. However, despite the drop, Malta still elected 50 percent women in 2019. Cyprus dropped from 17 percent in 2014 to zero women this year, while Estonia dropped from 50 to 33 percent. Hungary, Lithuania and Luxembourg made the greatest gains (19, 18 and 17 percentage points respectively) when we compare 2019 with 2014, followed by Slovenia and Latvia, both increasing their percentage of women MEPs by 13 points. Luxembourg, Slovenia and Latvia all elected 50 percent female MEPs.[16]

Age

As of 2019, the youngest MEP is Kira Marie Peter-Hansen of Denmark, who was 21 at the start of the July 2019 session, and is additionally the youngest person ever elected to the European Parliament.[20][21] The oldest MEP is Silvio Berlusconi of Italy, who was 82 at the start of the July 2019 session.[20]

Election of non-nationals

European citizens are eligible for election in the member state where they reside (subject to the residence requirements of that state); they do not have to be a national of that state. The following citizens have been elected in a state other than their native country;[22]

| Name | Year (first election) |

Nationality | State of election |

Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bárbara Dührkop Dührkop | 1987 | German | Spain | Socialist |

| Anita Pollack | 1989 | Australian[23] | UK | Socialist |

| Maurice Duverger | 1989 | French | Italy | GUE/NGL |

| Wilmya Zimmermann | 1994 | Dutch | Germany | Socialist |

| Oliver Dupuis | 1994 | Belgian | Italy | Radical |

| Daniel Cohn-Bendit | 1999 | German | France | Green |

| Monica Frassoni | 1999 | Italian | Belgium | Green |

| Miquel Mayol i Raynal | 2001 | French | Spain | Green |

| Bairbre de Brún | 2004 | Irish | UK | GUE/NGL |

| Willem Schuth | 2004 | Dutch | Germany | Liberal |

| Daniel Strož | 2004 | German | Czech Republic | GUE |

| Ari Vatanen | 2004 | Finnish | France | EPP |

| Derk Jan Eppink | 2009 | Dutch | Belgium | ECR |

| Marta Andreasen | 2009 | Spanish | UK | EFD |

| Anna Maria Corazza Bildt | 2009 | Italian | Sweden | EPP |

| Konstantina Kouneva | 2014 | Bulgarian | Greece | GUE/NGL |

| Henrik Overgaard-Nielsen | 2019 | Danish | UK | NI |

- 2009 figures incomplete

Observers

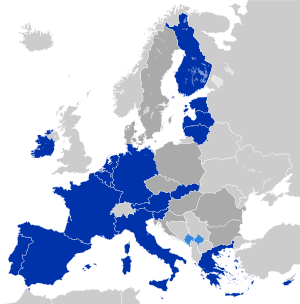

It is conventional for countries acceding to the European Union to send a number of observers to Parliament in advance. The number of observers and their method of appointment (usually by national parliaments) is laid down in the joining countries' Treaties of Accession.

Observers may attend debates and take part by invitation, but they may not vote or exercise other official duties. When the countries then become full member states, these observers become full MEPs for the interim period between accession and the next European elections. From 26 September 2005 to 31 December 2006, Bulgaria had 18 observers in Parliament and Romania 35. These were selected from government and opposition parties as agreed by the countries' national parliaments. Following accession on 1 January 2007, the observers became MEPs (with some personnel changes). Similarly, Croatia had 12 observer members from 17 April 2012, appointed by the Croatian parliament in preparation for its accession in 2013.[24]

See also

- EUobserver

- Apportionment in the European Parliament

- Category:Members of the European Parliament

- List of current Members of the European Parliament

References

![]()

![]()

- "Rule 1 in Rules of Procedure of the European Parliament (link is dead)". Europarl.europa.eu. 20 September 1976. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- "The European Parliament: historical background | Fact Sheets on the European Union | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Kreppel, Amie (2002). "The European Parliament and Supranational Party System" (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- Kreppel, Amie (2006). "Understanding the European Parliament from a Federalist Perspective: The Legislatures of the USA and EU Compared" (PDF). Center for European Studies, University of Florida. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- ""What to expect in the 2009–14 European Parliament": Analysis from a leading EU expert". European Parliament website. 2009. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- "Cohesion rates". Vote Watch. 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- European Parliament – Work in Session Retrieved 20 May 2010

- Indeed, Brussels is de facto the main base of the Parliament, as well as of the Commission and the Council. European Parliament in brief. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- "The European Parliament § Future organisation of the European Parliament". EUR-Lex.

A Protocol on the seats of the institutions will be annexed to the various Treaties, confirming the agreement reached at the Edinburgh European Council (December 1992) and stating that the European Parliament is to have its seat "in Strasbourg where the twelve periods of monthly plenary sessions, including the budget session, shall be held". Any additional plenary sessions are to be held in Brussels, as are the meetings of the various Parliamentary committees. 'The General Secretariat of the European Parliament and its departments shall remain in Luxembourg.'

- "The budget of the European Parliament". European Parliament web site. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Lungescu, Oana; Matzko, Laszlo (26 January 2004). "Germany blocks MEP pay rises". BBC News. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- Fresh start with new Members' Statute: The salary – a judgmental question. European Parliament Press Release. 7 January 2009.

- "EP adopts a single statute for MEPs".

- "EU Parliament Users' Guide Code of Conduct for Members" (PDF). European Parliament. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- Raibagi, Kashyap (22 May 2019). "In parliaments across Europe women face alarming levels of sexism, harassment and violence". VoxEurop/EDJNet. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- Raibagi, Kashyap (10 July 2019). "EU closes in on target for gender parity in the European Parliament". VoxEurop/EDJNet. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- Pavone, Gina (26 March 2019). "How gender balanced will the next European Parliament be?". OBC Transeuropa/EDJNet. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- "Analysis of political parties' and independent candidates' policies for gender balance in the European Parliament after the elections of 2014". Publications Office of the EU. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- Shreeves, Rosamund; Prpic, Martina; Claros, Eulalia. "Women in politics in the EU" (PDF). European Parliament. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- "40% of MEPs in EU Parliament are female, new figures show". EUObserver. 2 July 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Meet the European Parliament's youngest ever MEP". BBC News. 2 July 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- 1984 to 2004 from: Corbett, R. et al (2007) The European Parliament (7th ed) London, John Harper Publushing. p.21

- In addition, Australian and other Commonwealth citizens residing in the United Kingdom, up until Brexit, were eligible to vote and stand for election there.

- "Parliament to welcome Croatian "observer" members". European Parliament. 2 July 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

Further reading

- The European Parliament (eighth edition, 2011, John Harper publishing), by Richard Corbett, Francis Jacobs and Michael Shackleton.