Marxist historiography

Marxist historiography, or historical materialist historiography, is a school of historiography influenced by Marxism. The chief tenets of Marxist historiography are the centrality of social class and economic constraints in determining historical outcomes. While Marxist historians all follow the tenets of dialectical and historical materialism, the way Marxist historiography has developed in different regional and political contexts has varied. In particular, Marxist historiography has had unique trajectories of development in the West, in the Soviet Union, and in India, as well as in the Pan-Africanist and African American traditions, adapting to these specific regional and political conditions in different ways.

Marxist historiography has made contributions to the history of the working class, oppressed nationalities, and the methodology of history from below. The chief problematic aspect of some aspects of Marxist historiography has been an argument on the nature of history as determined or dialectical; this can also be stated as the relative importance of subjective and objective factors in creating outcomes. Marxist historians have also made this critique, particularly social historians who emphasize the need for a more humanist, historically contingent, Marxism.

Marxist history is sometimes criticized as deterministic:[1][2][3] with some practitioners positing a direction of history: towards an end state of history as classless human society. Marxist historiography, that is, the writing of Marxist history in line with the given historiographical principles, is often seen as a tool. Its aim is to bring those oppressed by history to self-consciousness, and to arm them with tactics and strategies from history: it is both a historical and a liberatory project.

Historians who use Marxist methodology, but disagree with the mainstream of Marxism, often describe themselves as marxist historians (with a lowercase M). Methods from Marxist historiography, such as class analysis, can be divorced from the liberatory intent of Marxist historiography; such practitioners often refer to their work as marxian or Marxian.

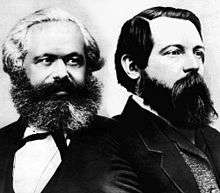

Marx and Engels

Friedrich Engels' most important historical contribution was Der deutsche Bauernkrieg (The German Peasants' War), which analysed social warfare in early Protestant Germany in terms of emerging capitalist classes. The German Peasants' War indicate the Marxist interest in history from below and class analysis, and attempts a dialectical analysis.

Marx's most important works on social and political history include The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, The Communist Manifesto, The German Ideology, and those chapters of Das Kapital dealing with the historical emergence of capitalists and proletarians from pre-industrial English society.

Engels' short treatise The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 (1870s) was salient in creating the socialist impetus in British politics.

Marx and labor

Key to understanding Marxist historiography is his view of labor. For Marx "historical reality is none other than objectified labor, and all conditions of labor given by nature, including the organic bodies of people, are merely preconditions and 'disappearing moments' of the labor process."[4] This emphasis on the physical as the determining factor in history represents a break from virtually all previous historians. Until Marx developed his theory of historical materialism, the overarching determining factor in the direction of history was some sort of divine agency. In Marx's view of history "God became a mere projection of human imagination" and more importantly "a tool of oppression".[5] There was no more sense of divine direction to be seen. History moved by the sheer force of human labor, and all theories of divine nature were a concoction of the ruling powers to keep the working people in check. For Marx, "The first historical act is... the production of material life itself."[6] As one might expect, Marxist history not only begins with labor, it ends in production: "history does not end by being resolved into "self-consciousness" as "spirit of the spirit," but that in it at each stage there is found a material result: a sum of productive forces, a historically created relation of individuals to nature and to one another, which is handed down to each generation from its predecessor..."[7] For further, and much more comprehensive, information on this topic, see historical materialism.

"Western" Historiography

A circle of historians inside the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) formed in 1946. They shared a common interest in "history from below" and class structure in early capitalist society. While some members of the group (most notably Christopher Hill and E. P. Thompson) left the CPGB after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the common points of British Marxist historiography continued in their works. They placed a great emphasis on the subjective determination of history. E. P. Thompson famously engaged Althusser in The Poverty of Theory, arguing that Althusser's theory overdetermined history, and left no space for historical revolt by the oppressed.

Thompson's The Making of the English Working Class is one of the works commonly associated with this group. Thompson's work is commonly considered the most influential work of history in the twentieth century and a crucial catalyst for social history and from social history to gender history and other studies of marginalized peoples.[8] His essay, "Time, Work, Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism" is also hugely influential and argues that industrial capitalism fundamentally altered (and accelerated) humans' relationship to time. Perhaps the most famous of the Communist Historians was E.B. Hobsbawm, who might bethe most famous and widely read historian of the 20th century. Hobsbawm is credited for establishing many of the basic historical arguments of current historiography and synthesizing huge amounts of modern historical data across time and space – most famously in his trilogy: The Age of Revolutions, The Age of Empires, and The Age of Extremes.[9] Eric Hobsbawm's Bandits is another example of this group's work.

C. L. R. James was also a great pioneer of the 'history from below' approach. Living in Britain when he wrote his most notable work The Black Jacobins (1938), he was an anti-Stalinist Marxist and so outside of the CPGB. The Black Jacobins was the first professional historical account of the greatest and only successful slave revolt in colonial American history, the Haitian Revolution. James's history is still touted as a remarkable work of history nearly a century after publication, an immense work of historical investigation, story-telling, and creativity.[10]

In the United States, Marxist historiography greatly influenced the history of slavery and labor history. Marxist historiography also greatly influenced French historians, including France's most famous and enduring historian Fernand Braudel, as well as Italian historians, most famously the Autonomous Marxist and micro-history fields.

In the Soviet Union

Marxist historiography suffered in the Soviet Union, as the government requested overdetermined historical writing. Soviet historians tended to avoid contemporary history (history after 1905) where possible and effort was predominantly directed at premodern history. As history was considered to be a politicised academic discipline, historians limited their creative output to avoid prosecution.

Notable histories include the Short Course History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolshevik), published in the 1930s, which was written in order to justify the nature of Bolshevik party life under Joseph Stalin.

In India

In India, D. D. Kosambi is considered the founding father of Marxist historiography. He was apologetic of Marxist revolution of Mao and thought of Socialist leader and Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru's policies as Pro Capitalism, He was although a mathematician but viewed Indian History from a Marxist view point[]The senior-most scholars of Marxist historiography are R. S. Sharma, Romila Thapar, Irfan Habib, D. N. Jha and K. N. Panikkar.[11]

One debate in Indian history that relates to a historical materialist schema is on the nature of feudalism in India. D. D. Kosambi in the 1960s outlined the idea of "feudalism from below" and "feudalism from above". R. S. Sharma largely agrees with Kosambi in his various books.[12][13][14][15] Most Indian Marxists argue that the economic origins of communalism are feudal remnants and the economic insecurities caused by slow development under a "world capitalist system."[16]

A number of historians have also debated Marxist historians and critically examined their analysis of history of India.[17][18][19][20] Since the late 1990s, Hindu nationalist scholars especially have polemicized against the Marxist tradition in India for neglecting what they believe to be the country's 'illustrious past.' Marxists are held responsible for aiding or defending Muslims, who figure in Hindu nationalist discourse as the enemy within.[21] An example of such a critique is Arun Shourie's Eminent Historians (1998).[22]

References

- Ben Fine; Alfredo Saad-Filho; Marco Boffo (January 2012). The Elgar Companion to Marxist Economics. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 212. ISBN 9781781001226.

- O'Rourke, J.J. (6 December 2012). The Problem of Freedom in Marxist Thought. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 5. ISBN 9789401021203.

- Stunkel, Kenneth (23 May 2012). Fifty Key Works of History and Historiography. Routledge. p. 247. ISBN 9781136723667.

- Andrey Maidansky. "The Logic of Marx's History," Russian Studies in Philosophy, vol. 51, no. 2 (Fall 2012): 45.

- Ernst Breisach. Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, 3rd Ed. (Chicago, Il: University of Chicago Press, 2007), p. 320.

- Fritz Stern. The Varieties of History: From Voltaire to the Present. Vintage Books Edition (New York: Random House: 1973), 150.

- Fritz Stern. The Varieties of History: From Voltaire to the Present. Vintage Books Edition (New York: Random House: 1973), 156–57.

- Scott,Joan. Gender and the Politics of History. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988; Revised edition, 1999

- Robin, Corey. "Eric Hobsbawm, The Communist Who Explained History" The New Yorker, May 9, 2019.

- Dubois, Laurent. The Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005.

- Bottomore, T. B. 1983. A Dictionary of Marxist thought. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- R S Sharma, Indian Feudalism (book), 2005

- R S Sharma, Early Medieval Indian Society: A Study in Feudalisation, Orient Longman, Kolkata, 2001, pp. 177–85

- R S Sharma, India's Ancient Past, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2005

- D N Jha, The Feudal Order: State Society and Ideology in Early Medieval India, Manohar Publishers, New Delhi, 2002

- Jogdand, Prahlad (1995). Dalit women in India: issues and perspective. p. 138.

- Lal, Kishori Saran. The Legacy of Muslim Rule in India. Aditya Prakashan. p. 67.

Marxists who always try to cover up the black spots of Muslim rule with thick coats of whitewash

- Seshadri, K. Indian Politics, Then and Now: Essays in Historical Perspective. Pragatee Prakashan. p. 5.

certain attempts made by some ultra-Marxist historians to justify and even whitewash tyrannical emperors of the medieval India

- Gupta, KR (2006). Studies in World Affairs, Volume 1. Atlantic Publisher. p. 249. ISBN 9788126904952.

- Wink, André (1991). Al-Hind the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: The Slave Kings and the Islamic Conquest : 11th–13th Centuries. Brill. p. 309.

apologists for Islam, as well as some marxist scholars in India have sometimes attempted to reduce Islamic iconoclasm..

- Guichard, Sylvie (2010). The Construction of History and Nationalism in India: Textbooks, Controversies and Politics. ISBN 9781136949319.

- Bryant, E. E. (2014). Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Cary, US: Oxford University Press

- Perry Anderson, In the tracks of Historical Materialism

- Paul Blackledge, Reflections on the Marxist Theory of History (2006)

- "Deciphering the past" International Socialism 112 (2006)