Empathy

Empathy is the capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing from within their frame of reference, that is, the capacity to place oneself in another's position.[1] Definitions of empathy encompass a broad range of emotional states. Types of empathy include cognitive empathy, emotional (or affective) empathy, and somatic empathy.[2][3]

_2.jpg)

Etymology

The English word empathy is derived from the Ancient Greek word ἐμπάθεια (empatheia, meaning "physical affection or passion").[4] This, in turn, comes from ἐν (en, "in, at") and πάθος (pathos, "passion" or "suffering").[5] The term was adapted by Hermann Lotze and Robert Vischer to create the German word Einfühlung ("feeling into"). This was described for the first time in English by the British critic and author, Vernon Lee, who explained "the word sympathy, with-feeling... is exercised only when our feelings enter, and are absorbed into, the form we perceive."[6] Einfühlung was officially translated by Edward B. Titchener in 1909 into the English word "empathy".[7][8][9] However, in modern Greek: εμπάθεια means, depending on context: prejudice, malevolence, malice, and hatred.[10]

Definitions

General

Empathy definitions encompass a broad range of emotional states, including caring for other people and having a desire to help them; experiencing emotions that match another person's emotions; discerning what another person is thinking or feeling;[11] and making less distinct the differences between the self and the other.[12] It can also be understood as having the separateness of defining oneself and another a blur.[13]

It also is the ability to feel and share another person's emotions. Some believe that empathy involves the ability to match another's emotions, while others believe that empathy involves being tenderhearted toward another person.[14]

Having empathy can include having the understanding that there are many factors that go into decision making and cognitive thought processes. Past experiences have an influence on the decision making of today. Understanding this allows a person to have empathy for individuals who sometimes make illogical decisions to a problem that most individuals would respond with an obvious response. Broken homes, childhood trauma, lack of parenting and many other factors can influence the connections in the brain which a person uses to make decisions in the future.[15]

Martin Hoffman is a psychologist who studied the development of empathy. According to Hoffman everyone is born with the capability of feeling empathy.[16]

Since empathy involves understanding the emotional states of other people, the way it is characterized is derived from the way emotions themselves are characterized. If, for example, emotions are taken to be centrally characterized by bodily feelings, then grasping the bodily feelings of another will be central to empathy. On the other hand, if emotions are more centrally characterized by a combination of beliefs and desires, then grasping these beliefs and desires will be more essential to empathy. The ability to imagine oneself as another person is a sophisticated imaginative process. However, the basic capacity to recognize emotions is probably innate[17] and may be achieved unconsciously. Yet it can be trained[18] and achieved with various degrees of intensity or accuracy.

Empathy necessarily has a "more or less" quality. The paradigm case of an empathic interaction, however, involves a person communicating an accurate recognition of the significance of another person's ongoing intentional actions, associated emotional states, and personal characteristics in a manner that the recognized person can tolerate. Recognitions that are both accurate and tolerable are central features of empathy.[19][20]

The human capacity to recognize the bodily feelings of another is related to one's imitative capacities, and seems to be grounded in an innate capacity to associate the bodily movements and facial expressions one sees in another with the proprioceptive feelings of producing those corresponding movements or expressions oneself.[21] Humans seem to make the same immediate connection between the tone of voice and other vocal expressions and inner feeling.

Distinctions between empathy and related concepts

Compassion and sympathy are terms associated with empathy. Definitions vary, contributing to the challenge of defining empathy. Compassion is often defined as an emotion people feel when others are in need, which motivates people to help them. Sympathy is a feeling of care and understanding for someone in need. Some include in sympathy an empathic concern, a feeling of concern for another, in which some scholars include the wish to see them better off or happier.[22]

Empathy is distinct also from pity and emotional contagion.[22] Pity is a feeling that one feels towards others that might be in trouble or in need of help as they cannot fix their problems themselves, often described as "feeling sorry" for someone. Emotional contagion is when a person (especially an infant or a member of a mob) imitatively "catches" the emotions that others are showing without necessarily recognizing this is happening.[23]

Alexithymia describes a deficiency in understanding, processing or describing emotions in oneself, unlike empathy which is about someone else.[24]

Classification

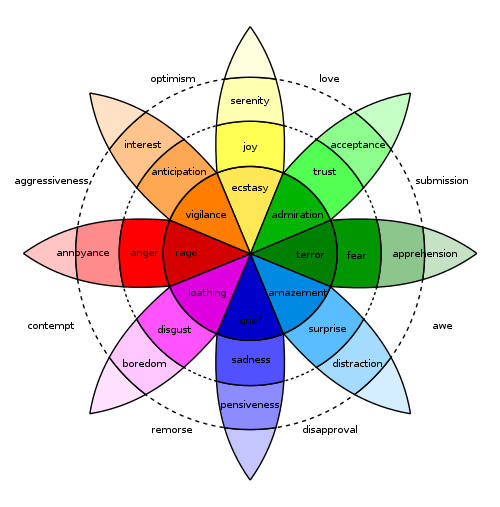

Empathy is generally divided into two major components:[25]

Affective empathy

Affective empathy, also called emotional empathy:[26] the capacity to respond with an appropriate emotion to another's mental states.[25] Our ability to empathize emotionally is based on emotional contagion:[26] being affected by another's emotional or arousal state.[27]

Affective empathy can be subdivided into the following scales:[25][28]

- Empathic concern: sympathy and compassion for others in response to their suffering.[25][29][30]

- Personal distress: self-centered feelings of discomfort and anxiety in response to another's suffering.[25][29][30] There is no consensus regarding whether personal distress is a basic form of empathy or instead does not constitute empathy.[29] There may be a developmental aspect to this subdivision. Infants respond to the distress of others by getting distressed themselves; only when they are 2 years old do they start to respond in other-oriented ways, trying to help, comfort and share.[29]

Cognitive empathy

Cognitive empathy: the capacity to understand another's perspective or mental state.[31][25][32] The terms cognitive empathy and theory of mind or mentalizing are often used synonymously, but due to a lack of studies comparing theory of mind with types of empathy, it is unclear whether these are equivalent.[33]

Although science has not yet agreed upon a precise definition of these constructs, there is consensus about this distinction.[34][35] Affective and cognitive empathy are also independent from one another; someone who strongly empathizes emotionally is not necessarily good in understanding another's perspective.[36][37]

Cognitive empathy can be subdivided into the following scales:[25][28]

- Perspective-taking: the tendency to spontaneously adopt others' psychological perspectives.[25]

- Fantasy: the tendency to identify with fictional characters.[25]

- Tactical (or "strategic") empathy: the deliberate use of perspective-taking to achieve certain desired ends.[38]

Somatic

- Somatic empathy is a physical reaction, probably based on mirror neuron responses, in the somatic nervous system.[2]

Development

Evolutionary across species

An increasing number of studies in animal behavior and neuroscience indicate that empathy is not restricted to humans, and is in fact as old as the mammals, or perhaps older. Examples include dolphins saving humans from drowning or from shark attacks. Professor Tom White suggests that reports of cetaceans having three times as many spindle cells—the nerve cells that convey empathy—in their brains as we do might mean these highly-social animals have a great awareness of one another's feelings.[39]

A multitude of behaviors has been observed in primates, both in captivity and in the wild, and in particular in bonobos, which are reported as the most empathetic of all the primates.[40][41] A recent study has demonstrated prosocial behavior elicited by empathy in rodents.[42]

Rodents have been shown to demonstrate empathy for cagemates (but not strangers) in pain.[43] One of the most widely read studies on the evolution of empathy, which discusses a neural perception-action mechanism (PAM), is the one by Stephanie Preston and de Waal.[44] This review postulates a bottom-up model of empathy that ties together all levels, from state matching to perspective-taking. For University of Chicago neurobiologist Jean Decety, [empathy] is not specific to humans. He argues that there is strong evidence that empathy has deep evolutionary, biochemical, and neurological underpinnings, and that even the most advanced forms of empathy in humans are built on more basic forms and remain connected to core mechanisms associated with affective communication, social attachment, and parental care.[13] Core neural circuits that are involved in empathy and caring include the brainstem, the amygdala, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, insula and orbitofrontal cortex.[45]

Since all definitions of empathy involves an element of for others, all distinctions between egoism and empathy fail at least for beings lacking self-awareness. Since the first mammals lacked a self-aware distinction between self and other, as shown by most mammals failing at mirror tests, the first mammals or anything more evolutionarily primitive than them cannot have had a context of default egoism requiring an empathy mechanism to be transcended. However, there are numerous examples in artificial intelligence research showing that simple reactions can carry out de facto functions the agents have no concept of, so this does not contradict evolutionary explanations of parental care. However, such mechanisms would be unadapted to self-other distinction and beings already dependent on some form of behavior benefitting each other or their offspring would never be able to evolve a form of self-other distinction that necessitated evolution of specialized non-preevolved and non-preevolvable mechanisms for retaining empathic behavior in the presence of self-other distinction, and so a fundamental neurological distinction between egoism and empathy cannot exist in any species.[46][47][48]

Ontogenetic development

By the age of two years, children normally begin to display the fundamental behaviors of empathy by having an emotional response that corresponds with another person's emotional state.[49] Even earlier, at one year of age, infants have some rudiments of empathy, in the sense that they understand that, just like their own actions, other people's actions have goals.[50][51][52] Sometimes, toddlers will comfort others or show concern for them at as early an age as two. Also during the second year, toddlers will play games of falsehood or "pretend" in an effort to fool others, and this requires that the child know what others believe before he or she can manipulate those beliefs.[53] In order to develop these traits, it is essential to expose your child to face-to-face interactions and opportunities and lead them away from a sedentary lifestyle.

According to researchers at the University of Chicago who used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), children between the ages of 7 and 12 years appear to be naturally inclined to feel empathy for others in pain. Their findings[54] are consistent with previous fMRI studies of pain empathy with adults. The research also found additional aspects of the brain were activated when youngsters saw another person intentionally hurt by another individual, including regions involved in moral reasoning.[55]

Despite being able to show some signs of empathy, including attempting to comfort a crying baby, from as early as 18 months to two years, most children do not show a fully fledged theory of mind until around the age of four.[56] Theory of mind involves the ability to understand that other people may have beliefs that are different from one's own, and is thought to involve the cognitive component of empathy.[31] Children usually become capable of passing "false belief" tasks, considered to be a test for a theory of mind, around the age of four. Individuals with autism often find using a theory of mind very difficult. e.g. the Sally–Anne test.[57][58]

Empathetic maturity is a cognitive structural theory developed at the Yale University School of Nursing and addresses how adults conceive or understand the personhood of patients. The theory, first applied to nurses and since applied to other professions, postulates three levels that have the properties of cognitive structures. The third and highest level is held to be a meta-ethical theory of the moral structure of care. Those adults operating with level-III understanding synthesize systems of justice and care-based ethics.[59]

Individual differences

Empathy in the broadest sense refers to a reaction of one individual to another's emotional state. Recent years have seen increased movement toward the idea that empathy occurs from motor neuron imitation. It cannot be said that empathy is a single unipolar construct but rather a set of constructs. In essence, not every individual responds equally and uniformly the same to various circumstances. The Empathic Concern scale assesses "other-oriented" feelings of sympathy and concern and the Personal Distress scale measures "self-oriented" feelings of personal anxiety and unease. The combination of these scales helps reveal those that might not be classified as empathetic and expands the narrow definition of empathy. Using this approach we can enlarge the basis of what it means to possess empathetic qualities and create a multi-faceted definition.[60]

Behavioral and neuroimaging research show that two underlying facets of the personality dimensions Extraversion and Agreeableness (the Warmth-Altruistic personality profile) are associated with empathic accuracy and increased brain activity in two brain regions important for empathic processing (medial prefrontal cortex and temporoparietal junction).[61]

Sex differences

The literature commonly indicates that females tend to have more cognitive empathy than males. Reviews, meta-analysis and studies of physiological measures, behavioral tests, and brain neuroimaging, however, have revealed some mixed findings.[62][63] Whereas some experimental and neuropsychological measures show no reliable sex effect, self-report data consistently indicates greater empathy in females. On average, female subjects score higher than males on the Empathy Quotient (EQ), while males tend to score higher on the Systemizing Quotient (SQ). Both males and females with autistic spectrum disorders usually score lower on the EQ and higher on SQ (see below for more detail on autism and empathy).[31] However, a series of studies, using a variety of neurophysiological measures, including MEG,[64] spinal reflex excitability,[65] electroencephalography[66][67] and N400 paradigm[68] have documented the presence of an overall gender difference in the human mirror neuron system, with female participants tending to exhibit stronger motor resonance than male participants. In addition, these aforementioned studies found that female participants tended to score higher on empathy self-report dispositional measures and that these measures positively correlated with the physiological response. Other studies show no significant difference, and instead suggest that gender differences are the result of motivational differences.[69][70]

A review published in the journal Neuropsychologia found that women tended to be better at recognizing facial effects, expression processing and emotions in general.[71] Men only tended to be better at recognizing specific behavior which includes anger, aggression and threatening cues.[71] A 2006 meta-analysis by researcher Rena A Kirkland in the journal North American Journal of Psychology found small significant sex differences favoring females in "Reading of the mind" test. "Reading of the mind" test is an advanced ability measure of cognitive empathy in which Kirkland's analysis involved 259 studies across 10 countries.[72] Another 2014 meta-analysis in the journal of Cognition and Emotion, found a small overall female advantage in non-verbal emotional recognition across 215 samples.[73]

Using fMRI, neuroscientist Tania Singer showed that empathy-related neural responses tended to be significantly lower in males when observing an "unfair" person experiencing pain.[74] An analysis from the journal of Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews also found that, overall, there are sex differences in empathy from birth, growing larger with age and which remains consistent and stable across lifespan.[75] Females, on average, were found to have higher empathy than males, while children with higher empathy regardless of gender continue to be higher in empathy throughout development.[75] Further analysis of brain tools such as event related potentials found that females who saw human suffering tended to have higher ERP waveforms than males.[75] Another investigation with similar brain tools such as N400 amplitudes found, on average, higher N400 in females in response to social situations which positively correlated with self-reported empathy.[75] Structural fMRI studies also found females to have larger grey matter volumes in posterior inferior frontal and anterior inferior parietal cortex areas which are correlated with mirror neurons in fMRI literature.[75] Females also tended to have a stronger link between emotional and cognitive empathy.[75] The researchers found that the stability of these sex differences in development are unlikely to be explained by any environment influences but rather might have some roots in human evolution and inheritance.[75] Throughout prehistory, females were the primary nurturers and caretakers of children; so this might have led to an evolved neurological adaptation for women to be more aware and responsive to non-verbal expressions. According to the Primary Caretaker Hypothesis, prehistoric males did not have the same selective pressure as primary caretakers; so therefore this might explain modern day sex differences in emotion recognition and empathy.[75]

Environmental influences

The environment has been another interesting topic of study. Many theorize that environmental factors, such as parenting style and relationships, play a significant role in the development of empathy in children. Empathy promotes pro social relationships, helps mediate aggression, and allows us to relate to others, all of which make empathy an important emotion among children.

A study done by Caroline Tisot looked at how a variety of environmental factors affected the development of empathy in young children. Parenting style, parent empathy, and prior social experiences were looked at. The children participating in the study were asked to complete an effective empathy measure, while the children's parents completed the Parenting Practices Questionnaire, which assesses parenting style, and the Balanced Emotional Empathy scale.

This study found that a few parenting practices – as opposed to parenting style as a whole – contributed to the development of empathy in children. These practices include encouraging the child to imagine the perspectives of others and teaching the child to reflect on his or her own feelings. The results also show that the development of empathy varied based on the gender of the child and parent. Paternal warmth was found to be significantly important, and was positively related to empathy within children, especially in boys. However, maternal warmth was negatively related to empathy within children, especially in girls.[76]

It has also been found that empathy can be disrupted due to trauma in the brain such as a stroke. In most cases empathy is usually impaired if a lesion or stroke occurs on the right side of the brain.[77] In addition to this it has been found that damage to the frontal lobe, which is primarily responsible for emotional regulation, can impact profoundly on a person's capacity to experience empathy toward another individual.[78] People who have suffered from an acquired brain injury also show lower levels of empathy according to previous studies. In fact, more than 50% of people who suffer from a traumatic brain injury self-report a deficit in their empathic capacity.[79] Again, linking this back to the early developmental stages of emotion, if emotional growth has been stunted at an early age due to various factors, empathy will struggle to infest itself in that individual's mind-set as a natural feeling, as they themselves will struggle to come to terms with their own thoughts and emotions. This is again suggestive of the fact that understanding one's own emotions is key in being able to identify with another individual's emotional state.

Empathic anger and distress

Anger

Empathic anger is an emotion, a form of empathic distress.[80] Empathic anger is felt in a situation where someone else is being hurt by another person or thing. It is possible to see this form of anger as a pro-social emotion.

Empathic anger has direct effects on both helping and punishing desires. Empathic anger can be divided into two sub-categories: trait empathic anger and state empathic anger.[81]

The relationship between empathy and anger response towards another person has also been investigated, with two studies basically finding that the higher a person's perspective taking ability, the less angry they were in response to a provocation. Empathic concern did not, however, significantly predict anger response, and higher personal distress was associated with increased anger.[82][83]

Influence on helping behavior

Emotions motivate individual behavior that aids in solving communal challenges as well as guiding group decisions about social exchange. Additionally, recent research has shown individuals who report regular experiences of gratitude engage more frequently in prosocial behaviors. Positive emotions like empathy or gratitude are linked to a more positive continual state and these people are far more likely to help others than those not experiencing a positive emotional state.[84] Thus, empathy's influence extends beyond relating to other's emotions, it correlates with an increased positive state and likeliness to aid others. Measures of empathy show that mirror neurons are activated during arousal of sympathetic responses and prolonged activation shows increased probability to help others.

Research investigating the social response to natural disasters looked at the characteristics associated with individuals who help victims. Researchers found that cognitive empathy, rather than emotional empathy, predicted helping behavior towards victims.[85] Others have posited that taking on the perspectives of others (cognitive empathy) allows these individuals to better empathize with victims without as much discomfort, whereas sharing the emotions of the victims (emotional empathy) can cause emotional distress, helplessness, victim-blaming, and ultimately can lead to avoidance rather than helping.[86]

Despite this evidence for empathy-induced altruistic motivation, egoistic explanations may still be possible. For example, one alternative explanation for the problem-specific helping pattern may be that the sequence of events in the same problem condition first made subjects sad when they empathized with the problem and then maintained or enhanced subjects’ sadness when they were later exposed to the same plight. Consequently, the negative state relief model would predict substantial helping among imagine-set subjects in the same condition, which is what occurred. An intriguing question arises from such findings concerning whether it is possible to have mixed motivations for helping. If this is the case, then simultaneous egoistic and altruistic motivations would occur. This would allow for a stronger sadness-based motivation to obscure the effects of an empathic concern-based altruistic motivation. The observed study would then have sadness as less intense than more salient altruistic motivation. Consequently, relative strengths of different emotional reactions, systematically related to the need situation, may moderate the predominance of egoistic or altruistic motivation.[87] But it has been shown that researchers in this area who have used very similar procedures sometimes obtain apparently contradictory results. Superficial procedural differences such as precisely when a manipulation is introduced could also lead to divergent results and conclusions. It is therefore vital for any future research to move toward even greater standardization of measurement. Thus, an important step in solving the current theoretical debate concerning the existence of altruism may involve reaching common methodological ground.[87]

Genetics

General

Research suggests that empathy is also partly genetically determined.[88] For instance, carriers of the deletion variant of ADRA2B show more activation of the amygdala when viewing emotionally arousing images.[89][90] The gene 5-HTTLPR seems to determine sensitivity to negative emotional information and is also attenuated by the deletion variant of ADRA2b.[91] Carriers of the double G variant of the OXTR gene were found to have better social skills and higher self-esteem.[92] A gene located near LRRN1 on chromosome 3 then again controls the human ability to read, understand and respond to emotions in others.[93]

Neuroscientific basis of empathy

Contemporary neuroscience has allowed us to understand the neural basis of the human mind's ability to understand and process emotion. Studies today enable us to see the activation of mirror neurons and attempt to explain the basic processes of empathy. By isolating these mirror neurons and measuring the neural basis for human mind reading and emotion sharing abilities,[94] science has come one step closer to finding the reason for reactions like empathy. Neuroscientists have already discovered that people scoring high on empathy tests have especially busy mirror neuron systems in their brains.[95] Empathy is a spontaneous sharing of affect, provoked by witnessing and sympathizing with another's emotional state. In a way we mirror or mimic the emotional response that we would expect to feel in that condition or context, much like sympathy. Unlike personal distress, empathy is not characterized by aversion to another's emotional response. Additionally, empathizing with someone requires a distinctly sympathetic reaction where personal distress demands avoidance of distressing matters. This distinction is vital because empathy is associated with the moral emotion sympathy, or empathetic concern, and consequently also prosocial or altruistic action.[94] Empathy leads to sympathy by definition unlike the over-aroused emotional response that turns into personal distress and causes a turning-away from another's distress.

In empathy, people feel what we believe are the emotions of another, which makes it both affective and cognitive by most psychologists.[11] In this sense, arousal and empathy promote prosocial behavior as we accommodate each other to feel similar emotions. For social beings, negotiating interpersonal decisions is as important to survival as being able to navigate the physical landscape.[84]

A meta-analysis of recent fMRI studies of empathy confirmed that different brain areas are activated during affective–perceptual empathy and cognitive–evaluative empathy.[96] Also, a study with patients with different types of brain damage confirmed the distinction between emotional and cognitive empathy.[26] Specifically, the inferior frontal gyrus appears to be responsible for emotional empathy, and the ventromedial prefrontal gyrus seems to mediate cognitive empathy.[26]

Research in recent years has focused on possible brain processes underlying the experience of empathy. For instance, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has been employed to investigate the functional anatomy of empathy.[97][98] These studies have shown that observing another person's emotional state activates parts of the neuronal network involved in processing that same state in oneself, whether it is disgust,[99] touch,[100][101] or pain.[102][103][104][105] The study of the neural underpinnings of empathy has received increased interest following the target paper published by Preston and Frans de Waal,[106] following the discovery of mirror neurons in monkeys that fire both when the creature watches another perform an action as well as when they themselves perform it.

In their paper, they argue that attended perception of the object's state automatically activates neural representations, and that this activation automatically primes or generates the associated autonomic and somatic responses (idea of perception-action-coupling),[107] unless inhibited. This mechanism is similar to the common coding theory between perception and action. Another recent study provides evidence of separate neural pathways activating reciprocal suppression in different regions of the brain associated with the performance of "social" and "mechanical" tasks. These findings suggest that the cognition associated with reasoning about the "state of another person's mind" and "causal/mechanical properties of inanimate objects" are neurally suppressed from occurring at the same time.[108][109]

A recent meta-analysis of 40 fMRI studies found that affective empathy is correlated with increased activity in the insula while cognitive empathy is correlated with activity in the mid cingulate cortex and adjacent dorsomedial prefrontal cortex.[110]

It has been suggested that mirroring-behavior in motor neurons during empathy may help duplicate feelings.[111] Such sympathetic action may afford access to sympathetic feelings for another and, perhaps, trigger emotions of kindness, forgiveness.[112]

Impairment

A difference in distribution between affective and cognitive empathy has been observed in various conditions. Psychopathy and narcissism have been associated with impairments in affective but not cognitive empathy, whereas bipolar disorder and borderline traits have been associated with deficits in cognitive but not affective empathy.[34] Autism spectrum disorders have been associated with various combinations, including deficits in cognitive empathy as well as deficits in both cognitive and affective empathy.[25][26][34][29][113][114] Schizophrenia, too, has been associated with deficits in both types of empathy.[115] However, even in people without conditions such as these, the balance between affective and cognitive empathy varies.[34]

Atypical empathic responses have been associated with autism and particular personality disorders such as psychopathy, borderline, narcissistic, and schizoid personality disorders; conduct disorder;[116] schizophrenia; bipolar disorder;[34] and depersonalization.[117] Lack of affective empathy has also been associated with sex offenders. It was found that offenders that had been raised in an environment where they were shown a lack of empathy and had endured the same type of abuse, felt less affective empathy for their victims.[118]

Autism

The interaction between empathy and autism is a complex and ongoing field of research. Several different factors are proposed to be at play.

A study of high-functioning adults with autistic spectrum disorders found an increased prevalence of alexithymia,[119] a personality construct characterized by the inability to recognize and articulate emotional arousal in oneself or others.[119][120][121] Based on fMRI studies, alexithymia is responsible for a lack of empathy.[122] The lack of empathic attunement inherent to alexithymic states may reduce quality[123] and satisfaction[124] of relationships. Recently, a study has shown that high-functioning autistic adults appear to have a range of responses to music similar to that of neurotypical individuals, including the deliberate use of music for mood management. Clinical treatment of alexithymia could involve using a simple associative learning process between musically induced emotions and their cognitive correlates.[125] A study has suggested that the empathy deficits associated with the autism spectrum may be due to significant comorbidity between alexithymia and autism spectrum conditions rather than a result of social impairment.[126]

One study found that, relative to typically developing children, high-functioning autistic children showed reduced mirror neuron activity in the brain's inferior frontal gyrus (pars opercularis) while imitating and observing emotional expressions.[127] EEG evidence revealed that there was significantly greater mu suppression in the sensorimotor cortex of autistic individuals. Activity in this area was inversely related to symptom severity in the social domain, suggesting that a dysfunctional mirror neuron system may underlie social and communication deficits observed in autism, including impaired theory of mind and cognitive empathy.[128] The mirror neuron system is essential for emotional empathy.[26]

Previous studies have suggested that autistic individuals have an impaired theory of mind. Theory of mind is the ability to understand the perspectives of others.[25] The terms cognitive empathy and theory of mind are often used synonymously, but due to a lack of studies comparing theory of mind with types of empathy, it is unclear whether these are equivalent.[25] Theory of mind relies on structures of the temporal lobe and the pre-frontal cortex, and empathy, i.e. the ability to share the feelings of others, relies on the sensorimotor cortices as well as limbic and para-limbic structures. The lack of clear distinctions between theory of mind and cognitive empathy may have resulted in an incomplete understanding of the empathic abilities of those with Asperger syndrome; many reports on the empathic deficits of individuals with Asperger syndrome are actually based on impairments in theory of mind.[25][129][130]

Studies have found that individuals on the autistic spectrum self-report lower levels of empathic concern, show less or absent comforting responses toward someone who is suffering, and report equal or higher levels of personal distress compared to controls.[29] The combination in those on the autism spectrum of reduced empathic concern and increased personal distress may lead to the overall reduction of empathy.[29] Professor Simon Baron-Cohen suggests that those with classic autism often lack both cognitive and affective empathy.[114] However, other research has found no evidence of impairment in autistic individuals' ability to understand other people's basic intentions or goals; instead, data suggests that impairments are found in understanding more complex social emotions or in considering others' viewpoints.[131] Research also suggests that people with Asperger syndrome may have problems understanding others' perspectives in terms of theory of mind, but the average person with the condition demonstrates equal empathic concern as, and higher personal distress, than controls.[25] The existence of individuals with heightened personal distress on the autism spectrum has been offered as an explanation as to why at least some people with autism would appear to have heightened emotional empathy,[29][113] although increased personal distress may be an effect of heightened egocentrism, emotional empathy depends on mirror neuron activity (which, as described previously, has been found to be reduced in those with autism), and empathy in people on the autism spectrum is generally reduced.[26][29] The empathy deficits present in autism spectrum disorders may be more indicative of impairments in the ability to take the perspective of others, while the empathy deficits in psychopathy may be more indicative of impairments in responsiveness to others’ emotions. These “disorders of empathy” further highlight the importance of the ability to empathize by illustrating some of the consequences to disrupted empathy development.[132]

The empathizing–systemizing theory (E-S) suggests that people may be classified on the basis of their capabilities along two independent dimensions, empathizing (E) and systemizing (S). These capabilities may be inferred through tests that measure someone's Empathy Quotient (EQ) and Systemizing Quotient (SQ). Five different "brain types" can be observed among the population based on the scores, which should correlate with differences at the neural level. In the E-S theory, autism and Asperger syndrome are associated with below-average empathy and average or above-average systemizing. The E-S theory has been extended into the Extreme Male Brain theory, which suggests that people with an autism spectrum condition are more likely to have an "Extreme Type S" brain type, corresponding with above-average systemizing but challenged empathy.[133]

It has been shown that males are generally less empathetic than females.[133] [134] The Extreme Male Brain (EMB) theory proposes that individuals on the autistic spectrum are characterized by impairments in empathy due to sex differences in the brain: specifically, people with autism spectrum conditions show an exaggerated male profile. A study showed that some aspects of autistic neuroanatomy seem to be extremes of typical male neuroanatomy, which may be influenced by elevated levels of fetal testosterone rather than gender itself.[133] [135][136] Another study involving brain scans of 120 men and women suggested that autism affects male and female brains differently; females with autism had brains that appeared to be closer to those of non-autistic males than females, yet the same kind of difference was not observed in males with autism.[137]

While the discovery of a higher incidence of diagnosed autism in some groups of second generation immigrant children was initially explained as a result of too little vitamin D during pregnancy in dark-skinned people further removed from the equator, that explanation did not hold up for the later discovery that diagnosed autism was most frequent in children of newly immigrated parents and decreased if they immigrated many years earlier as that would further deplete the body's store of vitamin D. Nor could it explain the similar effect on diagnosed autism for some European migrants America in the 1940s that was reviewed in the 2010s as a shortage of vitamin D was never a problem for these light-skinned immigrants to America. The decrease of diagnosed autism with the number of years the parents had lived in their new country also cannot be explained by the theory that the cause is genetic no matter if it is said to be caused by actual ethnic differences in autism gene prevalence or a selective migration of individuals predisposed for autism since such genes, if present, would not go away over time. It has therefore been suggested that autism is not caused by an innate deficit in a specific social circuitry in the brain, also citing other research suggesting that specificalized social brain mechanisms may not exist even in neurotypical people, but that particular features of appearance and/or minor details in behavior are met with exclusion from socialization that shows up as apparently reduced social ability.[138][139]

Psychopathy

Psychopathy is a personality disorder partly characterized by antisocial and aggressive behaviors, as well as emotional and interpersonal deficits including shallow emotions and a lack of remorse and empathy.[140][141] The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) list antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and dissocial personality disorder, stating that these have been referred to or include what is referred to as psychopathy.[142][143][144][145]

A large body of research suggests that psychopathy is associated with atypical responses to distress cues (e.g. facial and vocal expressions of fear and sadness), including decreased activation of the fusiform and extrastriate cortical regions, which may partly account for impaired recognition of and reduced autonomic responsiveness to expressions of fear, and impairments of empathy.[146][147][148][149][150] Studies on children with psychopathic tendencies have also shown such associations.[151][152][153] The underlying biological surfaces for processing expressions of happiness are functionally intact in psychopaths, although less responsive than those of controls.[150][151][152][153] The neuroimaging literature is unclear as to whether deficits are specific to particular emotions such as fear. Some recent fMRI studies have reported that emotion perception deficits in psychopathy are pervasive across emotions (positives and negatives).[154][155]

A recent study on psychopaths found that, under certain circumstances, they could willfully empathize with others, and that their empathic reaction initiated the same way it does for controls. Psychopathic criminals were brain-scanned while watching videos of a person harming another individual. The psychopaths' empathic reaction initiated the same way it did for controls when they were instructed to empathize with the harmed individual, and the area of the brain relating to pain was activated when the psychopaths were asked to imagine how the harmed individual felt. The research suggests how psychopaths could switch empathy on at will, which would enable them to be both callous and charming. The team who conducted the study say it is still unknown how to transform this willful empathy into the spontaneous empathy most people have, though they propose it could be possible to bring psychopaths closer to rehabilitation by helping them to activate their "empathy switch". Others suggested that despite the results of the study, it remained unclear whether psychopaths' experience of empathy was the same as that of controls, and also questioned the possibility of devising therapeutic interventions that would make the empathic reactions more automatic.[156][157]

Work conducted by Professor Jean Decety with large samples of incarcerated psychopaths offers additional insights. In one study, psychopaths were scanned while viewing video clips depicting people being intentionally hurt. They were also tested on their responses to seeing short videos of facial expressions of pain. The participants in the high-psychopathy group exhibited significantly less activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, amygdala and periaqueductal gray parts of the brain, but more activity in the striatum and the insula when compared to control participants.[158] In a second study, individuals with psychopathy exhibited a strong response in pain-affective brain regions when taking an imagine-self perspective, but failed to recruit the neural circuits that were activated in controls during an imagine-other perspective—in particular the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and amygdala—which may contribute to their lack of empathic concern.[159]

It was predicted that people who have high levels of psychopathy would have sufficient levels of cognitive empathy but would lack in their ability to use affective empathy. People that scored highly on psychopathy measures were less likely to portray affective empathy. There was a strong negative correlation showing that psychopathy and affective empathy correspond strongly. The DANVA-2 portrayed those who scored highly on the psychopathy scale do not lack in recognising emotion in facial expressions. Therefore, individuals who have high scores on psychopathy and do not lack in perspective-talking ability but do lack in compassion and the negative incidents that happen to others.[160]

Despite studies suggesting deficits in emotion perception and imagining others in pain, professor Simon Baron-Cohen claims psychopathy is associated with intact cognitive empathy, which would imply an intact ability to read and respond to behaviors, social cues and what others are feeling. Psychopathy is, however, associated with impairment in the other major component of empathy—affective (emotional) empathy—which includes the ability to feel the suffering and emotions of others (what scientists would term as emotional contagion), and those with the condition are therefore not distressed by the suffering of their victims. Such a dissociation of affective and cognitive empathy has indeed been demonstrated for aggressive offenders.[161] Those with autism, on the other hand, are claimed to be often impaired in both affective and cognitive empathy.[114]

One problem with the theory that the ability to turn empathy on and off constitutes psychopathy is that such a theory would classify socially sanctioned violence and punishment as psychopathy, as it means suspending empathy towards certain individuals and/or groups. The attempt to get around this by standardizing tests of psychopathy for cultures with different norms of punishment is criticized in this context for being based on the assumption that people can be classified in discrete cultures while cultural influences are in reality mixed and every person encounters a mosaic of influences (e.g. non-shared environment having more influence than family environment). It is suggested that psychopathy may be an artefact of psychiatry's standardization along imaginary sharp lines between cultures, as opposed to an actual difference in the brain.[162][163]

Other conditions

Research indicates atypical empathic responses are also correlated with a variety of other conditions.

Borderline personality disorder is characterized by extensive behavioral and interpersonal difficulties that arise from emotional and cognitive dysfunction.[164] Dysfunctional social and interpersonal behavior has been shown to play a crucial role in the emotionally intense way people with borderline personality disorder react.[165] While individuals with borderline personality disorder may show their emotions too much, several authors have suggested that they might have a compromised ability to reflect upon mental states (impaired cognitive empathy), as well as an impaired theory of mind.[165] People with borderline personality disorder have been shown to be very good at recognizing emotions in people's faces, suggesting increased empathic capacities.[166][167] It is, therefore, possible that impaired cognitive empathy (the capacity for understanding another person's experience and perspective) may account for borderline personality disorder individuals' tendency for interpersonal dysfunction, while "hyper-emotional empathy" may account for the emotional over-reactivity observed in these individuals.[165] One primary study confirmed that patients with borderline personality disorder were significantly impaired in cognitive empathy, yet there was no sign of impairment in affective empathy.[165]

One diagnostic criterion of narcissistic personality disorder is a lack of empathy and an unwillingness or inability to recognize or identify with the feelings and needs of others.[168]

Characteristics of schizoid personality disorder include emotional coldness, detachment, and impaired affect corresponding with an inability to be empathetic and sensitive towards others.[169][170][171]

A study conducted by Jean Decety and colleagues at the University of Chicago demonstrated that subjects with aggressive conduct disorder elicit atypical empathic responses to viewing others in pain.[116] Subjects with conduct disorder were at least as responsive as controls to the pain of others but, unlike controls, subjects with conduct disorder showed strong and specific activation of the amygdala and ventral striatum (areas that enable a general arousing effect of reward), yet impaired activation of the neural regions involved in self-regulation and metacognition (including moral reasoning), in addition to diminished processing between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex.[116]

Schizophrenia is characterized by impaired affective empathy,[11][34] as well as severe cognitive and empathy impairments as measured by the Empathy Quotient (EQ).[115] These empathy impairments are also associated with impairments in social cognitive tasks.[115]

Bipolar individuals have been observed to have impaired cognitive empathy and theory of mind, but increased affective empathy.[34][172] Despite cognitive flexibility being impaired, planning behavior is intact. It has been suggested that dysfunctions in the prefrontal cortex could result in the impaired cognitive empathy, since impaired cognitive empathy has been related with neurocognitive task performance involving cognitive flexibility.[172]

Lieutenant Colonel Dave Grossman, in his book On Killing, suggests that military training artificially creates depersonalization in soldiers, suppressing empathy and making it easier for them to kill other human beings.[117]

In educational contexts

Another growing focus of investigation is how empathy manifests in education between teachers and learners.[173] Although there is general agreement that empathy is essential in educational settings, research has found that it is difficult to develop empathy in trainee teachers.[174] According to one theory, there are seven components involved in the effectiveness of intercultural communication; empathy was found to be one of the seven. This theory also states that empathy is learnable. However, research also shows that it is more difficult to empathize when there are differences between people including status, culture, religion, language, skin colour, gender, age and so on.[174]

An important target of the method Learning by teaching (LbT) is to train systematically and, in each lesson, teach empathy. Students have to transmit new content to their classmates, so they have to reflect continuously on the mental processes of the other students in the classroom. This way it is possible to develop step-by-step the students' feeling for group reactions and networking. Carl R. Rogers pioneered research in effective psychotherapy and teaching which espoused that empathy coupled with unconditional positive regard or caring for students and authenticity or congruence were the most important traits for a therapist or teacher to have. Other research and publications by Tausch, Aspy, Roebuck. Lyon, and meta-analyses by Cornelius-White, corroborated the importance of these person-centered traits.[175][176]

In intercultural contexts

In order to achieve intercultural empathy, psychologists have employed empathy training. One study hypothesized that empathy training would increase the measured level of relational empathy among the individuals in the experimental group when compared to the control group.[177] The study also hypothesized that empathy training would increase communication among the experimental group, and that perceived satisfaction with group dialogue would also increase among the experimental group. To test this, the experimenters used the Hogan Empathy Scale, the Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory, and questionnaires. Using these measures, the study found that empathy training was not successful in increasing relational empathy. Also, communication and satisfaction among groups did not increase as a result of the empathy training. While there didn't seem to be a clear relationship between empathy and relational empathy training, the study did report that "relational empathy training appeared to foster greater expectations for a deep dialogic process resulting in treatment differences in perceived depth of communication".

US researchers William Weeks, Paul Pedersen et al. state that developing intercultural empathy enables the interpretation of experiences or perspectives from more than one worldview.[178] Intercultural empathy can also improve self-awareness and critical awareness of one's own interaction style as conditioned by one's cultural views[179] and promote a view of self-as-process.[180]

Applications

The empathy-altruism relationship also has broad and practical implications. Knowledge of the power of the empathic feeling to evoke altruistic motivation may lead to strategies for learning to suppress or avoid these feelings; such numbing or loss of the capacity to feel empathy for clients has been suggested as a factor in the experience of burnout among case workers in helping professions. Awareness of this impending futile effort— nurses caring for terminal patients or pedestrians walking by the homeless—may make individuals try to avoid feelings of empathy in order to avoid the resulting altruistic motivation. Promoting an understanding about the mechanisms by which altruistic behavior is driven, whether it is from minimizing sadness or the arousal of mirror neurons allows people to better cognitively control their actions. However, empathy-induced altruism may not always produce pro-social effects. It could lead one to increase the welfare of those for whom empathy is felt at the expense of other potential pro-social goals, thus inducing a type of bias. Researchers suggest that individuals are willing to act against the greater collective good or to violate their own moral principles of fairness and justice if doing so will benefit a person for whom empathy is felt.[181]

On a more positive note, aroused individuals in an empathetic manner may focus on the long-term welfare rather than just the short-term of those in need. Empathy-based socialization is very different from current practices directed toward inhibition of egoistic impulses through shaping, modeling and internalized guilt. Therapeutic programs built around facilitating altruistic impulses by encouraging perspective taking and empathetic feelings might enable individuals to develop more satisfactory interpersonal relations, especially in the long-term. At a societal level, experiments have indicated that empathy-induced altruism can be used to improve attitudes toward stigmatized groups, even used to improve racial attitudes, actions toward people with AIDS, the homeless and even convicts. Such resulting altruism has also been found to increase cooperation in competitive situations.[182]

In the field of positive psychology, empathy has also been compared with altruism and egotism. Altruism is behavior that is aimed at benefitting another person, while egotism is a behavior that is acted out for personal gain. Sometimes, when someone is feeling empathetic towards another person, acts of altruism occur. However, many question whether or not these acts of altruism are motivated by egotistical gains. According to positive psychologists, people can be adequately moved by their empathies to be altruistic,[14][183] and there are others who consider the wrong moral leaning perspectives and having empathy can lead to polarization, ignite violence and motivate dysfunctional behavior in relationships.[184]

Practical issues

The capacity to empathize is a revered trait in society.[25] Empathy is considered a motivating factor for unselfish, prosocial behavior,[185] whereas a lack of empathy is related to antisocial behavior.[25][186][187][188]

Proper empathic engagement helps an individual understand and anticipate the behavior of another. Apart from the automatic tendency to recognize the emotions of others, one may also deliberately engage in empathic reasoning. Two general methods have been identified here. An individual may simulate fictitious versions of the beliefs, desires, character traits and context of another individual to see what emotional feelings it provokes. Or, an individual may simulate an emotional feeling and then access the environment for a suitable reason for the emotional feeling to be appropriate for that specific environment.[44]

Some research suggests that people are more able and willing to empathize with those most similar to themselves. In particular, empathy increases with similarities in culture and living conditions. Empathy is more likely to occur between individuals whose interaction is more frequent.[189][190] A measure of how well a person can infer the specific content of another person's thoughts and feelings has been developed by William Ickes.[69] In 2010, team led by Grit Hein and Tania Singer gave two groups of men wristbands according to which football team they supported. Each participant received a mild electric shock, then watched another go through the same pain. When the wristbands matched, both brains flared: with pain, and empathic pain. If they supported opposing teams, the observer was found to have little empathy.[191] Bloom calls improper use of empathy and social intelligence as a tool can lead to shortsighted actions and parochialism,[192] he further defies conventional supportive research findings as gremlins from biased standards. He ascertains empathy as an exhaustive process that limits us in morality and if low empathy makes for bad people, bundled up in that unsavoury group would be many who have Asperger's or autism and reveals his own brother is severely autistic. Early indicators for a lack of empathy:

- Frequently finding oneself in prolonged arguments

- Forming opinions early and defending them vigorously

- Thinking that other people are overly sensitive

- Refusing to listen to other points of view

- Blaming others for mistakes

- Not listening when spoken to

- Holding grudges and having difficulty to forgive

- Inability to work in a team

There are concerns that the empathizer's own emotional background may affect or distort what emotions they perceive in others. [193] It is evidenced that societies that promote individualism have lower ability for empathy.[194] Empathy is not a process that is likely to deliver certain judgments about the emotional states of others. It is a skill that is gradually developed throughout life, and which improves the more contact we have with the person with whom one empathizes. Empathizers report finding it easier to take the perspective of another person when they have experienced a similar situation,[195] as well as experience greater empathic understanding.[196] Research regarding whether similar past experience makes the empathizer more accurate is mixed.[195][196]

Ethical issues

The extent to which a person's emotions are publicly observable, or mutually recognized as such has significant social consequences. Empathic recognition may or may not be welcomed or socially desirable. This is particularly the case where we recognize the emotions that someone has towards us during real time interactions. Based on a metaphorical affinity with touch, philosopher Edith Wyschogrod claims that the proximity entailed by empathy increases the potential vulnerability of either party.[197] The appropriate role of empathy in our dealings with others is highly dependent on the circumstances. For instance, Tania Singer says that clinicians or caregivers must be objective to the emotions of others, to not over-invest their own emotions for the other, at the risk of draining away their own resourcefulness.[198] Furthermore, an awareness of the limitations of empathic accuracy is prudent in a caregiving situation.

Empathic distress fatigue

Excessive empathy can lead to empathic distress fatigue, especially if it is associated with pathological altruism. The medical risks are fatigue, occupational burnout, guilt, shame, anxiety, and depression.[199][200]

Disciplinary approaches

Philosophy

Ethics

In his 2008 book, How to Make Good Decisions and Be Right All the Time:Solving the Riddle of Right and Wrong, writer Iain King presents two reasons why empathy is the "essence" or "DNA" of right and wrong. First, he argues that empathy uniquely has all the characteristics we can know about an ethical viewpoint[201] – including that it is "partly self-standing", and so provides a source of motivation that is partly within us and partly outside, as moral motivations seem to be.[202] This allows empathy-based judgements to have sufficient distance from a personal opinion to count as "moral". His second argument is more practical: he argues, "Empathy for others really is the route to value in life", and so the means by which a selfish attitude can become a moral one. By using empathy as the basis for a system of ethics, King is able to reconcile ethics based on consequences with virtue-ethics and act-based accounts of right and wrong.[203] His empathy-based system has been taken up by some Buddhists,[204] and is used to address some practical problems, such as when to tell lies,[205] and how to develop culturally-neutral rules for romance.

In the 2007 book The Ethics of Care and Empathy, philosopher Michael Slote introduces a theory of care-based ethics that is grounded in empathy. His claim is that moral motivation does, and should, stem from a basis of empathic response. He claims that our natural reaction to situations of moral significance are explained by empathy. He explains that the limits and obligations of empathy and in turn morality are natural. These natural obligations include a greater empathic, and moral obligation to family and friends, along with an account of temporal and physical distance. In situations of close temporal and physical distance, and with family or friends, our moral obligation seems stronger to us than with strangers at a distance naturally. Slote explains that this is due to empathy and our natural empathic ties. He further adds that actions are wrong if and only if they reflect or exhibit a deficiency of fully developed empathic concern for others on the part of the agent.[206]

Phenomenology

In phenomenology, empathy describes the experience of something from the other's viewpoint, without confusion between self and other. This draws on the sense of agency. In the most basic sense, this is the experience of the other's body and, in this sense, it is an experience of "my body over there". In most other respects, however, the experience is modified so that what is experienced is experienced as being the other's experience; in experiencing empathy, what is experienced is not "my" experience, even though I experience it. Empathy is also considered to be the condition of intersubjectivity and, as such, the source of the constitution of objectivity.[207]

History

Some postmodern historians such as Keith Jenkins in recent years have debated whether or not it is possible to empathize with people from the past. Jenkins argues that empathy only enjoys such a privileged position in the present because it corresponds harmoniously with the dominant liberal discourse of modern society and can be connected to John Stuart Mill's concept of reciprocal freedom. Jenkins argues the past is a foreign country and as we do not have access to the epistemological conditions of by gone ages we are unable to empathize.[208]

It is impossible to forecast the effect of empathy on the future. A past subject may take part in the present by the so-called historic present. If we watch from a fictitious past, can tell the present with the future tense, as it happens with the trick of the false prophecy. There is no way of telling the present with the means of the past.[209]

Psychotherapy

Heinz Kohut is the main introducer of the principle of empathy in psychoanalysis. His principle applies to the method of gathering unconscious material. The possibility of not applying the principle is granted in the cure, for instance when you must reckon with another principle, that of reality.

In evolutionary psychology, attempts at explaining pro-social behavior often mention the presence of empathy in the individual as a possible variable. While exact motives behind complex social behaviors are difficult to distinguish, the "ability to put oneself in the shoes of another person and experience events and emotions the way that person experienced them" is the definitive factor for truly altruistic behavior according to Batson's empathy-altruism hypothesis. If empathy is not felt, social exchange (what's in it for me?) supersedes pure altruism, but if empathy is felt, an individual will help by actions or by word, regardless of whether it is in their self-interest to do so and even if the costs outweigh potential rewards.[210]

Business and management

In the 2009 book Wired to Care, strategy consultant Dev Patnaik argues that a major flaw in contemporary business practice is a lack of empathy inside large corporations. He states that lacking any sense of empathy, people inside companies struggle to make intuitive decisions and often get fooled into believing they understand their business if they have quantitative research to rely upon. Patnaik claims that the real opportunity for companies doing business in the 21st century is to create a widely held sense of empathy for customers, pointing to Nike, Harley-Davidson, and IBM as examples of "Open Empathy Organizations". Such institutions, he claims, see new opportunities more quickly than competitors, adapt to change more easily, and create workplaces that offer employees a greater sense of mission in their jobs.[211] In the 2011 book The Empathy Factor, organizational consultant Marie Miyashiro similarly argues the value of bringing empathy to the workplace, and offers Nonviolent Communication as an effective mechanism for achieving this.[212] In studies by the Management Research Group, empathy was found to be the strongest predictor of ethical leadership behavior out of 22 competencies in its management model, and empathy was one of the three strongest predictors of senior executive effectiveness.[213]

Measurement

Research into the measurement of empathy has sought to answer a number of questions: who should be carrying out the measurement? What should pass for empathy and what should be discounted? What unit of measure (UOM) should be adopted and to what degree should each occurrence precisely match that UOM are also key questions that researchers have sought to investigate.

Researchers have approached the measurement of empathy from a number of perspectives.

Behavioral measures normally involve raters assessing the presence or absence of certain either predetermined or ad-hoc behaviors in the subjects they are monitoring. Both verbal and non-verbal behaviors have been captured on video by experimenters such as Truax.[214] Other experimenters, including Mehrabian and Epstein,[215] have required subjects to comment upon their own feelings and behaviors, or those of other people involved in the experiment, as indirect ways of signaling their level of empathic functioning to the raters.

Physiological responses tend to be captured by elaborate electronic equipment that has been physically connected to the subject's body. Researchers then draw inferences about that person's empathic reactions from the electronic readings produced.[216]

Bodily or "somatic" measures can be looked upon as behavioral measures at a micro level. Their focus is upon measuring empathy through facial and other non-verbally expressed reactions in the empathizer. These changes are presumably underpinned by physiological changes brought about by some form of "emotional contagion" or mirroring.[216] These reactions, whilst appearing to reflect the internal emotional state of the empathizer, could also, if the stimulus incident lasted more than the briefest period, be reflecting the results of emotional reactions that are based upon more pieces of thinking through (cognitions) associated with role-taking ("if I were him I would feel ...").

Paper-based indices involve one or more of a variety of methods of responding. In some experiments, subjects are required to watch video scenarios (either staged or authentic) and to make written responses which are then assessed for their levels of empathy;[217] scenarios are sometimes also depicted in printed form.[218] Measures also frequently require subjects to self-report upon their own ability or capacity for empathy, using Likert-style numerical responses to a printed questionnaire that may have been designed to tap into the affective, cognitive-affective or largely cognitive substrates of empathic functioning. Some questionnaires claim to have been able to tap into both cognitive and affective substrates.[219] More recent paper-based tools include The Empathy Quotient (EQ) created by Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright[220] which comprises a self-report questionnaire consisting of 60 items.

For the very young, picture or puppet-story indices for empathy have been adopted to enable even very young, pre-school subjects to respond without needing to read questions and write answers.[221] Dependent variables (variables that are monitored for any change by the experimenter) for younger subjects have included self reporting on a 7-point smiley face scale and filmed facial reactions.[222]

A certain amount of confusion exists about how to measure empathy. These may be rooted in another problem: deciding what empathy is and what it is not. In general, researchers have until now been keen to pin down a singular definition of empathy which would allow them to design a measure to assess its presence in an exchange, in someone's repertoire of behaviors or within them as a latent trait. As a result, they have been frequently forced to ignore the richness of the empathic process in favor of capturing surface, explicit self-report or third-party data about whether empathy between two people was present or not. In most cases, instruments have unfortunately only yielded information on whether someone had the potential to demonstrate empathy.[223] Gladstein[224] summarizes the position noting that empathy has been measured from the point of view of the empathizer, the recipient for empathy and the third-party observer. He suggests that since the multiple measures used have produced results that bear little relation to one another, researchers should refrain from making comparisons between scales that are in fact measuring different things. He suggests that researchers should instead stipulate what kind of empathy they are setting out to measure rather than simplistically stating that they are setting out to measure the unitary phenomenon "empathy"; a view more recently endorsed by Duan and Hill.[225]

In the field of medicine, a measurement tool for carers is the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy, Health Professional Version (JSPE-HP).[226]

The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) is among the oldest published measurement tools (first published in 1983) that provides a multi-dimensional assessment of empathy. It comprises a self-report questionnaire of 28 items, divided into four 7-item scales covering the above subdivisions of affective and cognitive empathy.[25][28][25][28] Among more recent multi-dimensional scales is the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE, first published in 2011).[227]

The Empathic Experience Scale is a 30-item questionnaire that was developed to cover the measurement of empathy from a phenomenological perspective on intersubjectivity, which provides a common basis for the perceptual experience (vicarious experience dimension) and a basic cognitive awareness (intuitive understanding dimension) of others' emotional states.[228]

International comparison of country-wide empathy

In a 2016 study by a US research team, self-report data from the mentioned Interreactivity Index (see Measurement) were compared across countries. From the surveyed nations, the five highest empathy scores had (in descending order): Ecuador, Saudi Arabia, Peru, Denmark and United Arab Emirates. Bulgaria, Poland, Estonia, Venezuela and Lithuania ranked as having lowest empathy scores.[229]

Other animals and empathy between species

Researchers Zanna Clay and Frans de Waal studied the socio-emotional development of the bonobo chimpanzee.[230] They focused on the interplay of numerous skills such as empathy-related responding, and how different rearing backgrounds of the juvenile bonobo affected their response to stressful events, related to themselves (loss of a fight) and of stressful events of others. It was found that the bonobos sought out body contact as a coping mechanism with one another. A finding of this study was that the bonobos sought out more body contact after watching a distressing event upon the other bonobos rather than their individually experienced stressful event. Mother-reared bonobos as opposed to orphaned bonobos sought out more physical contact after a stressful event happened to another. This finding shows the importance of mother-child attachment and bonding, and how it may be crucial to successful socio-emotional development, such as empathic-like behaviors.

Empathic-like responding has been observed in chimpanzees in various different aspects of their natural behaviors. For example, chimpanzees are known to spontaneously contribute comforting behaviors to victims of aggressive behavior in natural and unnatural settings, a behavior recognized as consolation. Researchers Teresa Romero and co-workers observed these empathic and sympathetic-like behaviors in chimpanzees at two separate outdoor housed groups.[231] The act of consolation was observed in both of the groups of chimpanzees. This behavior is found in humans, and particularly in human infants. Another similarity found between chimpanzees and humans is that empathic-like responding was disproportionately provided to individuals of kin. Although comforting towards non-family chimpanzees was also observed, as with humans, chimpanzees showed the majority of comfort and concern to close/loved ones. Another similarity between chimpanzee and human expression of empathy is that females provided more comfort than males on average. The only exception to this discovery was that high-ranking males showed as much empathy-like behavior as their female counterparts. This is believed to be because of policing-like behavior and the authoritative status of high-ranking male chimpanzees.

It is thought that species that possess a more intricate and developed prefrontal cortex have more of an ability of experiencing empathy. It has however been found that empathic and altruistic responses may also be found in sand dwelling Mediterranean ants. Researcher Hollis studied the Cataglyphis cursor sand dwelling Mediterranean ant and their rescue behaviors by ensnaring ants from a nest in nylon threads and partially buried beneath the sand.[232] The ants not ensnared in the nylon thread proceeded to attempt to rescue their nest mates by sand digging, limb pulling, transporting sand away from the trapped ant, and when efforts remained unfruitful, began to attack the nylon thread itself; biting and pulling apart the threads. Similar rescue behavior was found in other sand-dwelling Mediterranean ants, but only Cataglyphis floricola and Lasius grandis species of ants showed the same rescue behaviors of transporting sand away from the trapped victim and directing attention towards the nylon thread. It was observed in all ant species that rescue behavior was only directed towards nest mates. Ants of the same species from different nests were treated with aggression and were continually attacked and pursued, which speaks to the depths of ants discriminative abilities. This study brings up the possibility that if ants have the capacity for empathy and/or altruism, these complex processes may be derived from primitive and simpler mechanisms.

Canines have been hypothesized to share empathic-like responding towards human species. Researchers Custance and Mayer put individual dogs in an enclosure with their owner and a stranger.[233] When the participants were talking or humming, the dog showed no behavioral changes, however when the participants were pretending to cry, the dogs oriented their behavior toward the person in distress whether it be the owner or stranger. The dogs approached the participants when crying in a submissive fashion, by sniffing, licking and nuzzling the distressed person. The dogs did not approach the participants in the usual form of excitement, tail wagging or panting. Since the dogs did not direct their empathic-like responses only towards their owner, it is hypothesized that dogs generally seek out humans showing distressing body behavior. Although this could insinuate that dogs have the cognitive capacity for empathy, this could also mean that domesticated dogs have learned to comfort distressed humans through generations of being rewarded for that specific behavior.

When witnessing chicks in distress, domesticated hens, Gallus gallus domesticus show emotional and physiological responding. Researchers Edgar, Paul and Nicol[234] found that in conditions where the chick was susceptible to danger, the mother hens heart rate increased, vocal alarms were sounded, personal preening decreased and body temperature increased. This responding happened whether or not the chick felt as if they were in danger. Mother hens experienced stress-induced hyperthermia only when the chick's behavior correlated with the perceived threat. Animal maternal behavior may be perceived as empathy, however, it could be guided by the evolutionary principles of survival and not emotionality.

At the same time, humans can empathize with other species. A study by Miralles et al. (2019) showed that human empathic perceptions (and compassionate reactions) toward an extended sampling of organisms are strongly negatively correlated with the divergence time separating them from us. In other words, the more phylogenetically close a species is to us, the more likely we are to feel empathy and compassion towards it.[235]

See also

- Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion (book by Paul Bloom)

- Artificial empathy

- Attribution (psychology)

- Digital empathy

- Emotional contagion

- Emotional intelligence

- Emotional literacy

- Empathic concern

- Empathizing–systemizing theory

- Ethnocultural empathy

- Fake empathy

- Grounding in communication

- Highly sensitive person

- Humanistic coefficient

- Identification (psychology)

- Life skills

- Mimpathy

- Moral emotions

- Nonviolent Communication

- Oxytocin

- People skills

- Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

- Schema (psychology)

- Self-conscious emotions

- Sensibility

- Simulation theory of empathy

- Social emotions

- Soft skills

- Theory of mind in animals