Thibodaux, Louisiana

Thibodaux (/ˈtɪbədoʊ/ TIB-ə-doh) is a city in and the parish seat of Lafourche Parish, Louisiana, United States,[4] along the banks of Bayou Lafourche in the northwestern part of the parish. The population was 14,567 at the 2010 census. Thibodaux is a principal city of the Houma–Bayou Cane–Thibodaux Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Thibodaux, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

| City of Thibodaux | |

Downtown | |

| Nickname(s): Queen City of Lafourche | |

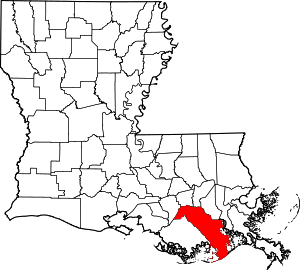

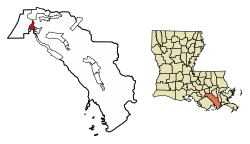

Location of Thibodaux in Lafourche Parish, Louisiana. | |

.svg.png) Location of Louisiana in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 29°47′32″N 90°49′12″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | Lafourche |

| Incorporated | 1830 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Tommy Eschete[1] |

| Area | |

| • City | 6.48 sq mi (16.79 km2) |

| • Land | 6.48 sq mi (16.79 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 13 ft (4 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • City | 14,566 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 14,425 |

| • Density | 2,225.74/sq mi (859.30/km2) |

| • Metro | 208,178 |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 70301, 70302, 70310 |

| Area code(s) | 985 |

| FIPS code | 22-75425 |

| Website | http://ci.thibodaux.la.us |

Thibodaux is nicknamed "Queen City of Lafourche."

History

The first European colonists were French, who settled here in the 18th century when the area was claimed as part of La Louisiane. The French colonists brought people from Africa in bondage as slaves to work on and develop sugar cane plantations.

This was incorporated as a town in 1830 under the name Thibodauxville, in honor of local planter Henry Schuyler Thibodaux. He provided land for the village center and served as acting governor of Louisiana in 1824.[5] The area was developed in the antebellum period for sugar cane plantations, and Thibodaux was the trading center of the agricultural area. The name was changed to Thibodeaux in 1838. The current spelling Thibodaux was officially adopted in 1918.

In 1896, the first rural free delivery of mail in Louisiana began in Thibodaux. It was the second such RFD in the United States.

Civil War

In October 1862, following the Battle of Georgia Landing (Labadieville), Thibodaux was occupied by the Union Army under Godfrey Weitzel. Before they left the city, the Confederates under General Alfred Mouton (later killed in the Battle of Mansfield in De Soto Parish), burned the depot, the bridges, sugar, and supplies that they could not carry with them.[6] In 1863, the Union under James P. Major temporarily abandoned Thibodaux but soon returned.

Winters reports that

terrified Negroes and whites raced into the town announcing that 3,000 Confederate cavalrymen were en route to attack Thibodaux and Lafourche Crossing. Union Colonel Thomas W. Cahill ordered an immediate retreat. The bayou bridges were burned, three field guns were destroyed, and as many of the men and the horses as possible were loaded . . . and ordered to Raceland. . . . Ammunition was destroyed, horses abandoned, and four field pieces were left behind.[7]

Once the area was again under Union control, they ordered people of African descent held as slaves free and to be paid wages. White planters in Thibodaux complained about having to negotiate labor contracts for the African workers. Alexander F. Pugh, a large sugar planter near Thibodaux, complained that

Negroes and federal officers took up too much time in negotiating new labor contracts. Part of the delay was occasioned by the fact that the Negroes were dissatisfied with the settlements from the past year, and additional delays were brought about because of changes in labor rules and regulations.[8] Pugh wrote in his diary: "I have agreed with the Negroes today to pay them monthly wages. It was very distasteful to me, but I could do no better. Everybody else in the neighborhood has agreed to pay the same, and mine [laborers] would listen to nothing else."[9]

Post-Reconstruction and Thibodaux massacre

In the late 19th century, after having taken back control of the state government following the Reconstruction era by use of paramilitary forces such as the White League, which suppressed black voting, white Democrats continued to consolidate their power over the state government. In the late 1880s they were challenged temporarily by a biracial coalition of Populists and Republicans. Because blacks were skilled sugar workers, they briefly retained more rights and political power than did African Americans in the north of the state on cotton plantations in this period.

But from 1880, through the Louisiana Sugar Producer's Association, some 200 major planters worked to regain slave conditions and control of workers, adopting uniform pay, withholding 80 percent of the workers' pay until after harvest, and making them accept scrip, redeemable only at plantation stores, rather than cash. There was repeated labor unrest as cane workers struck intermittently against conditions.

The Knights of Labor organized a chapter in 1886 in Shreveport, and attracted many cane workers seeking better conditions. A sugar cane workers' strike in Lafourche and three neighboring parishes involved 10,000 workers, 1,000 of whom were white, during the critical "rolling period". Planters were alarmed both by outside labor organizations and the thought of losing their total crops. The governor called in the State militia at the planters' request, who protected strikebreakers and evicted black workers. The strike was broken in Terrebone Parish.

Paramilitary forces closed off Thibodaux, where numerous black workers had taken refuge. On November 22, they began to massacre black workers and their families, killing at least 50 in what is called the "Thibodaux massacre" of November 22, 1887, Whites inflicted one of the bloodiest labor disputes in U.S. history against black people in Thibodaux. Casualties including wounded and missing were said to be in the hundreds, but there has never been an accurate count. The cane workers returned to the plantations under slavery conditions created by white planters. In the following months, Knights of Labor organizers continued to disappear.[10][11] The massacre and subsequent disenfranchisement of blacks at the turn of the century, and white Democrats' imposition of Jim Crow, ended labor organizing of cane workers until the 1940s.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 5.47 square miles (14.2 km2), all land.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 1,242 | — | |

| 1860 | 1,380 | 11.1% | |

| 1870 | 1,922 | 39.3% | |

| 1880 | 1,515 | −21.2% | |

| 1890 | 2,078 | 37.2% | |

| 1900 | 3,253 | 56.5% | |

| 1910 | 3,824 | 17.6% | |

| 1920 | 3,526 | −7.8% | |

| 1930 | 4,442 | 26.0% | |

| 1940 | 5,851 | 31.7% | |

| 1950 | 7,730 | 32.1% | |

| 1960 | 13,403 | 73.4% | |

| 1970 | 15,028 | 12.1% | |

| 1980 | 15,810 | 5.2% | |

| 1990 | 14,035 | −11.2% | |

| 2000 | 14,431 | 2.8% | |

| 2010 | 14,566 | 0.9% | |

| Est. 2019 | 14,425 | [3] | −1.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] | |||

As of the census[13] of 2000, there were 14,431 people, 5,500 households, and 3,355 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,636.8 people per square mile (1,018.6/km2). There were 6,004 housing units at an average density of 1,097.0 per square mile (423.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 64.04% White, 33.76% African American, 0.37% Native American, 0.64% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.26% from other races, and 0.90% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.03% of the population.

There were 5,500 households, out of which 29.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.1% were married couples living together, 19.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.0% were non-families. 31.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 3.10.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 24.6% under the age of 18, 17.3% from 18 to 24, 25.1% from 25 to 44, 18.9% from 45 to 64, and 14.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females, there were 85.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 79.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $26,697, and the median income for a family was $36,551. Males had a median income of $31,464 versus $21,144 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,966. About 20.6% of families and 25.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 36.3% of those under age 18 and 18.2% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

The Roman Catholic patron saints of Thibodaux are Saint Valérie, an early Christian martyr, and Saint Vitalis of Milan, her husband, also a martyr. A life-sized reliquary of Saint Valérie, containing an arm bone, was brought to Thibodaux in 1868 and is displayed in her shrine in St. Joseph Co-Cathedral in Thibodaux. A smaller reliquary, with a relic of St. Vitalis, is displayed near St. Valérie's reliquary. St. Valérie has traditionally been invoked for intercession in protecting Thibodaux from hurricanes.

Richard D'Alton Williams, a well-known 19th-century Irish patriot, poet, and physician, died of tuberculosis in Thibodaux in 1862, and is buried in St. Joseph Cemetery. His headstone was erected that year by Irish members of the 8th New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry, then encamped in Thibodaux. A famous Mississippi blues musician, Eddie "Guitar Slim" Jones, is buried in Thibodaux, where he often played, and where his manager, Hosea Hill, resided. Two-term Governor of Louisiana Francis T. Nicholls is buried in the Episcopal Cemetery on Jackson Street.

Government

The mayor of Thibodaux is elected at-large and is currently Tommy Eschete.[1] The city council of seven is elected from five single-member districts, and two at-large members.[14] Thibodaux is in Parish Council Districts 1, 2, 3, and 4.[15]

In the Louisiana Legislature, Thibodaux is represented by Rep. Jerome Richard (I-Thibodaux) and Sen. Bret Allain (R-Jeanerette). In the United States Congress, it is represented by Rep. Garret Graves (R-Baton Rouge), Sen. Bill Cassidy (R- Baton Rouge) and Sen. John Neely Kennedy (R- Madisonville).

The Louisiana Office of Juvenile Justice operates the Thibodaux Office in Thibodaux.[16]

The United States Postal Service operates the Thibodaux Post Office.[17]

ZIP codes for Thibodaux are 70301, 70302, and 70310. Thibodaux's area code is 985.

Education

Residents are zoned to schools in the Lafourche Parish Public Schools.[18]

Zoned elementary schools include:

- South Thibodaux Elementary School

- Thibodaux Elementary School

- W.S. Lafargue Elementary School

Zoned middle schools include:

- East Thibodaux Middle School

- West Thibodaux Middle School

- Sixth Ward Middle School

Thibodaux residents are zoned to Thibodaux High School.

Catholic schools include:

- Edward Douglas White Catholic High School

- St. Genevieve Catholic Elementary

- St. Joseph Catholic Elementary

Colleges:

From 1950 until 1968 C.M. Washington High School served as the segregated school for African Americans in Thibodaux.[19]

Media

The local newspaper is The Daily Comet. It was founded in 1889 as Lafourche Comet. It was owned by The New York Times Company from 1979 until 2011. The company sold this and other regional newspapers to Halifax Media Group.

Cable television and Internet are provided in Thibodaux by Reserve Telecommunications, AT&T, and Charter Spectrum.

In popular culture

- The family and city name "Thibodaux" is mentioned in Hank Williams' "Jambalaya (On The Bayou)". In 1972 Leon Russell had the song "Cajun Love Song", in which Thibodaux is mentioned. It is also mentioned in the 1970s Jerry Reed song "Amos Moses," in the 1990s George Strait song "Adalida," in Dan Baird's 1992 song "Dixie Beauxderaunt," the 1999 Jimmy Buffett song "I Will Play for Gumbo," the 2008 Toby Keith song "Creole Woman," and "Thibodaux" is the title of a song by jazz singer Marcia Ball.

- The 1989 motion picture Fletch Lives took place in Thibodaux.

Notable people

- Eric Andolsek, player for the Detroit Lions[20]

- Charlton Reid Beattie, U.S. federal judge; practiced law in Thibodaux

- Rezin Bowie, Louisiana politician and inventor of the Bowie knife; resided six years on Acadia Plantation near Thibodaux

- Braxton Bragg, Confederate general, slave-owner and planter on Bayou Lafourche in 1856-1861

- Adrian Joseph Caillouet, U.S. federal judge

- Kody Chamberlain, comic book writer and artist[21]

- Monnie T. Cheves, professor at Nichols State University; member of the Louisiana House of Representatives from Natchitoches Parish from 1952 to 1960[22]

- Thomas G. Clausen, professor at Nicholls State University from 1967 to 1972; last elected state superintendent of education, 1984-1988[23]

- Mark Davis, professional basketball player[24]

- Ronald Dominique, serial killer

- Francis Dugas, state representative from Lafourche Parish from 1956 to 1960; Robert F. Kennon's running-mate for lieutenant governor in 1963

- Alan Faneca, American football offensive lineman, nine-time Pro-Bowler, Super Bowl champion (XL)[25]

- Jeremy Gaubert, winner of 2009 World Poker Open

- Mary Gauthier, folk singer-songwriter; grew up in Thibodaux

- Jarvis Green, defensive end for the Denver Broncos[26]

- Walter Guion, U.S. senator from Louisiana

- Damian Johnson, player for the Minnesota Golden Gophers men's basketball team[27]

- Clay Knobloch, former Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana

- Louis La Garde, soldier, medical doctor and author

- Theodore K. Lawless, dermatologist, medical researcher, and philanthropist

- Oliver Marcelle, baseball player

- Graham Patrick Martin, actor TV: Major Crimes, The Closer, Two and a Half Men; Movies: The Anna Nicole Story, Bukowski, Somewhere Slow

- Whitmell P. Martin, congressman from Louisiana; moved to Thibodaux

- Jordan Mills, football player

- Numa F. Montet, congressman from Louisiana

- Doug Moreau, football player

- Drake Nevis, football player

- Francis T. Nicholls, two-term governor of Louisiana; moved to Ridgefield Plantation near Thibodaux

- Harvey Peltier, Jr., state senator from 1964 to 1976;[28] first president of the University of Louisiana System trustees from 1975 until his death in 1980[29]

- Harvey Peltier, Sr., member of both houses of the Louisiana State Legislature from Thibodaux, 1924-1940[30]

- Jerome "Dee" Richard, current member of the Louisiana House of Representatives from Thibodaux; one of two Independents in the legislature[31]

- John Robichaux, jazz musician[32]

- Greg Robinson, offensive lineman for the Detroit Lions

- Junius P. Rodriguez, academic and author

- Tom Roussel, football player

- Dustin Schuetter, actor, producer, director and screenwriter

- Billy Tauzin, congressman who lived in Thibodaux while he was in office[33]

- Theodore Ward, noted African-American playwright[34]

- Edward Douglass White, Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court[35]

- Edward Douglass White Sr., governor of Louisiana[36]

- Alfred C. Williams, state representative for East Baton Rouge Parish since 2012; former Thibodaux resident[37]

References

- "City of Thibodaux, Louisiana - Mayors Office". Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism. "Thibodaux Historical Marker".

- John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963, ISBN 0-8071-0834-0, p. 162

- Winters, p. 290

- Winters, p. 409

- Winters, pp. 409-410

- Douglass, "Thibodaux Massacre", University of Virginia, accessed 4 December 2007

- C. Wyatt Evans, "The Ambiguities of Labor in Sugar Country", History.net, accessed 4 December 2007

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "City of Thibodaux Louisiana - Council". Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- Lafourche Parish Government (2010). "Lafourche Parish Government Website". Archived from the original on 2010-07-04. Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- "Regional offices." Louisiana Office of Juvenile Justice. Retrieved on December 26, 2017. "1077 Highway 3185, Thibodaux, LA, United States"

- "THIBODAUX." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on December 26, 2017. "910 CANAL BLVD THIBODAUX, LA 70301-9998"

- Legendre, Raymond (2008-07-14). "Alumni group seeks to change school's name". Houma Today. Retrieved 2016-12-04. - See image of the historic plaque

- NFL Enterprises LLC (2010). "Eric Andolsek". Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- Chamberlain, Kody (2006). "kodychamberlain.com - Official website of Kody Chamberlain - Kody Chamberlain". Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- "In Memoriam: Monnie T. Cheves". Alexandria Daily Town Talk. August 17, 1988. p. D3. Archived from the original on September 10, 2014. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- "Thomas G. Clausen, p. 18" (PDF). parlouisiana.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 11, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- Sports Reference *LLC (2010). "Mark Davis NBA & ABA Statistics". Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- "Arizona Cardinals Website - Alan Faneca Bio". Archived from the original on 2010-08-21. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- NFL Enterprises LLC (2010). "Jarvis Green". Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- University of Minnesota (2010). "Damian Johnson Bio - Gophersports.com - Official Web Site of University of Minnesota Athletics". NeuLion. Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- "Membership in the Louisiana State Senate, 1880-Present" (PDF). senate.la.gov. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- "History". ulsystem.net. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- "Pot Of Gold For A Nervy Cajun, September 19, 1966". si.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- "Membership of the Louisiana House of Representatives, 1812-2016" (PDF). house.louisiana.gov. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- Hurricane Brassband (2009-05-11). "John Robichaux". Archived from the original on 2010-07-06. Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- Barone, Michael; and Ujifusa, Grant. The Almanac of American Politics 1988', p. 494. National Journal, 1987.

- Ward, Elise Virginia (2008). "Theodore Ward". Bridges Web Services. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- "WHITE, Edward Douglass - Biographical Information". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- Encyclopedia Louisiana (2001-12-20). "State Governors of Louisiana: Edward Douglas White". Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- "Alfred C. Williams". intelius.com. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thibodaux, Louisiana. |