Raiders of the Lost Ark

Raiders of the Lost Ark (later marketed as Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark) is a 1981 American action-adventure film directed by Steven Spielberg and written by Lawrence Kasdan from a story by George Lucas and Philip Kaufman. It was produced by Frank Marshall for Lucasfilm Ltd., with Lucas and Howard Kazanjian as executive producers. The film originated from Lucas's desire to create a modern version of the serial films of the 1930s and 1940s.

| Raiders of the Lost Ark | |

|---|---|

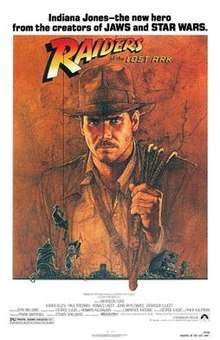

Theatrical release poster by Richard Amsel | |

| Directed by | Steven Spielberg |

| Produced by | Frank Marshall |

| Screenplay by | Lawrence Kasdan |

| Story by | |

| Starring | |

| Music by | John Williams |

| Cinematography | Douglas Slocombe |

| Edited by | Michael Kahn |

Production company | Lucasfilm Ltd. |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $20 million[2] |

| Box office | $389.9 million[3] |

The first installment in the Indiana Jones franchise, the film stars Harrison Ford as archaeologist Indiana Jones, who battles a group of Nazis searching for the Ark of the Covenant. It co-stars Karen Allen as Indiana's former lover, Marion Ravenwood; Paul Freeman as Indiana's rival, French archaeologist René Belloq; John Rhys-Davies as Indiana's sidekick, Sallah; Ronald Lacey as Gestapo agent Arnold Toht; and Denholm Elliott as Indiana's colleague, Marcus Brody. Production was based at Elstree Studios, England, but filming also took place in La Rochelle, France, Tunisia, Hawaii, and California from June to September 1980.

Raiders of the Lost Ark earned $389.9 million worldwide, becoming the highest-grossing film of 1981, and remains one of the highest-grossing films adjusted for inflation. It was nominated for eight Academy Awards in 1982, including Best Picture, and won for Best Art Direction, Film Editing, Sound, and Visual Effects with a fifth Academy Award: a Special Achievement Award for Sound Effects Editing. It is often considered one of the greatest films ever made.[4][5][6][7][8] In 1999, it was included in the U.S. Library of Congress' National Film Registry as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". The film began a franchise starting with the prequel Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. It also includes a prequel television series (The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles) and numerous video games.

Plot

In 1936, American archaeologist Indiana Jones braves an ancient booby-trapped temple in Peru to retrieve a golden idol. After superating various challenges, including traitorous guides, he is confronted by rival archaeologist René Belloq and the indigenous Hovito people. Surrounded and outnumbered, Jones is forced to surrender the idol to Belloq but manages to escape aboard a waiting seaplane.

Two Army Intelligence agents later interview Jones at Marshall College, where he holds a teaching position, and inform him that the Nazis are working with his old mentor, Abner Ravenwood, whom Jones studied under at the University of Chicago. The Nazis know that Ravenwood is the leading expert on the ancient city of Tanis in Egypt, and that he possesses the headpiece of an ancient Egyptian artifact known as "the Staff of Ra". Jones deduces that the Nazis are searching for the Ark of the Covenant, believing it will grant their armies invincibility. The agents authorize Jones to recover the Ark.

He travels to Nepal to discover that Ravenwood has died and the headpiece is in the possession of Ravenwood's daughter Marion. Jones visits Marion at her tavern before a group of thugs arrive with their Nazi commander Arnold Toht, seeking the headpiece. A gunfight erupts, the bar is set ablaze and the headpiece lands in the flames. Toht severely burns his hand trying to retrieve it and flees the bar in agony. Jones and Marion escape with the headpiece, and Marion decides to accompany Jones in his search. They travel to Cairo, Egypt, where they meet up with Jones' friend and skilled digger Sallah. He informs them that Belloq and the Nazis are digging for "the Well of Souls", believed to lead to the Ark's location, with a replica of the headpiece created from the scar on Toht's hand. Jones and Marion are attacked by a group of Nazi soldiers, and Marion is seemingly killed in an explosion during the resulting chase. After a confrontation with Belloq in a local bar Jones regroups with Sallah, and they realize that the Nazi headpiece is incomplete and that the Nazis are digging in the wrong place, as they only have part of the information regarding the Well's location.

Jones and Sallah infiltrate the Nazi dig site. Jones finds Marion alive, bound and gagged in a tent; he does not set her free in fear of alerting the Nazis, but promises to come back for her later. Jones and Sallah use their staff to locate the Ark in the snake-infested Well of Souls. They fend off the snakes using fire and gasoline before reaching the stone coffin containing the Ark. Belloq, Toht, and Nazi officer Colonel Dietrich arrive and seize the Ark from Jones, before imprisoning him and Marion in the crypt. The two escape to a local airstrip, where Jones gets into a fistfight with a mechanic and destroys the flying wing that was to transport the Ark to Berlin, Germany. The panicked Nazis load the Ark onto a truck, but Jones manages to catch up on horseback, hijack the truck, defeat the Nazis, and make arrangements to transport the Ark to London aboard tramp steamer Bantu Wind. In the cargo hold, the Nazi symbols stenciled on the crate containing the Ark spontaneously burn away.

The next day a Nazi U-boat intercepts the ship. Belloq, Toht, and Dietrich seize the Ark and Marion but cannot locate Jones, who stows away aboard the U-boat and travels with them to an island in the Aegean Sea. Once there, Belloq plans to test the power of the Ark before presenting it to Hitler. Jones reveals himself and threatens to destroy the Ark with an anti-tank rocket, but Belloq calls his bluff and Jones surrenders.

The Nazis take Jones and Marion to an area where the Ark will be opened and tie them to a post to observe. Dressed as an Israelite kohen gadol, Belloq performs a ceremonial opening of the Ark by invoking a prayer recited in synagogues when a Torah scroll is removed from the ark,[9] but finds only sand inside. As Jones warns Marion to keep her eyes shut, spirits emerge from the Ark, eventually revealing themselves to be angels of death. Flames then form above the opened Ark and bolts of energy shoot through the gathered Nazi soldiers, killing them all. The extreme heat causes Dietrich's body to shrivel, Toht's face to melt, and Belloq's head to explode. Flames then engulf and vaporize the remains of the doomed assembly in a whirlwind of fire before the Ark seals itself shut. Jones and Marion open their eyes and find the area wiped clean along with their ropes burned off, and embrace.

Back in Washington, D.C., Jones and Marcus Brody receive a large payment from the United States government for securing the Ark. The Army Intelligence agents explain that the Ark has been moved to a secure facility for further study by "top men." Jones, Marion, and Brody depart as the Ark is crated up and put into storage among countless other crates in a large government warehouse.

Cast

- Harrison Ford as Indiana Jones, an archaeology professor who often embarks on perilous adventures to obtain rare artifacts. Jones claims that he has no belief in the supernatural, only to have his skepticism challenged when he discovers the Ark. Spielberg suggested casting Ford as Jones, but Lucas objected, stating that he did not want Ford to become his "Bobby De Niro" or "that guy I put in all my movies"—a reference to Martin Scorsese's frequent collaborations with Robert De Niro.[10] Desiring a lesser known actor, Lucas persuaded Spielberg to help him search for a new talent. Among the actors who auditioned were Tim Matheson, Peter Coyote, John Shea, and Tom Selleck. Selleck was originally offered the role, but became unavailable for the part because of his commitment to the television series Magnum, P.I..[10][11] In June 1980, three weeks away from filming,[12] Spielberg persuaded Lucas to cast Ford after producers Frank Marshall and Kathleen Kennedy were impressed by his performance as Han Solo in The Empire Strikes Back.[13]

- Karen Allen as Marion Ravenwood, a spirited, tough former lover of Indiana's. She is the daughter of Abner Ravenwood, Indiana Jones' mentor, and owns a bar in Nepal. Allen was cast after auditioning with Matheson and John Shea. Spielberg was interested in her, as he had seen her performance in National Lampoon's Animal House. Sean Young had previously auditioned for the part,[10] while Debra Winger turned it down.[14]

- Paul Freeman as Dr. René Belloq, Jones' rival. Belloq is also an archaeologist after the Ark, but he is working for the Nazis. Spielberg cast Freeman after seeing him in Death of a Princess.[15] Singer Jacques Dutronc auditioned for the role but lost out to Freeman.

- Ronald Lacey as Major Arnold Toht, a sadistic Gestapo agent, who tries to torture Marion Ravenwood for the headpiece of the Staff of Ra. Lacey was cast as he reminded Spielberg of Peter Lorre.[10] Spielberg had originally offered the role to Roman Polanski, who was intrigued at the opportunity to work with Spielberg but decided to turn down the role because he wouldn't be able to make the trip to Tunisia.[16] Klaus Kinski was also offered the role, but he hated the script,[17] calling it "moronically shitty".[18]

- John Rhys-Davies as Sallah, "the best digger in Egypt" according to Indiana, who has been hired by the Nazis to help them excavate Tanis. He is an old friend of Indiana, and agrees to help him obtain the Ark, though he fears disturbing it. Spielberg initially approached Danny DeVito to play Sallah, but he could not play the part due to scheduling conflicts. Spielberg cast Rhys-Davies after seeing his performance in Shōgun.[10]

- Denholm Elliott as Dr. Marcus Brody, a museum curator, who buys the artifacts Indiana obtains for display in his museum. The U.S. government agents approach him with regard to the Ark's recovery, and he sets up a meeting between them and Indiana Jones. Spielberg hired Elliott as he was a big fan of the actor, who had performed in some of his favorite British and American films.[10]

Additionally, Wolf Kahler appears as Colonel Dietrich, a ruthless German officer leading the operation to secure the Ark. Alfred Molina, in his film debut, portrays Satipo, one of Jones' guides through the South American jungle, while George Harris plays Simon Katanga, captain of the Bantu Wind. Anthony Higgins appears as Major Gobler, Colonel Dietrich's right-hand-man, and Vic Tablian appears as both Barranca and the Monkey Man.

Don Fellows and William Hootkins appear as Colonel Musgrove and Major Eaton, two Army Intelligence agents. Producer Frank Marshall cameos as a pilot in the airplane fight sequence. The stunt team was ill, so he took the role instead. The scene required him to shoot for three days in a hot cockpit, which he joked was over "140 degrees". [10] Pat Roach plays the Nazi mechanic with whom Jones brawls in this sequence, as well as a massive Sherpa who battles Jones in Marion's bar. He had the rare opportunity to be killed twice in one film.[19] Special-effects supervisor Dennis Muren made a cameo as a Nazi spy on the seaplane Jones takes from San Francisco to Manila.[20] Terry Richards performed the role of the Cairo swordsman who is shot by Jones.

Production

Development

In 1973, George Lucas wrote The Adventures of Indiana Smith.[21] Like Star Wars, which he also wrote, it was an opportunity to create a modern version of the film serials of the 1930s and 1940s.[10] Lucas discussed the concept with Philip Kaufman, who worked with him for several weeks and came up with the Ark of the Covenant as the plot device.[22] Kaufman was told about the Ark by his dentist when he was a child.[23] The project stalled when Clint Eastwood hired Kaufman to direct The Outlaw Josey Wales.[22] Lucas shelved the idea, deciding to concentrate on his outer space adventure that would become Star Wars. In late May 1977, Lucas was in Hawaii, trying to escape the enormous success of Star Wars. Friend and colleague Steven Spielberg was also there, on vacation from work on Close Encounters of the Third Kind. While building a sand castle at the Mauna Kea Beach Hotel,[24] Spielberg expressed an interest in directing a James Bond film. Lucas convinced Spielberg that he had conceived a character "better than James Bond" and explained the concept of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Spielberg loved it, calling it "a James Bond film without the hardware",[25] although he told Lucas that the surname 'Smith' was not right for the character. Lucas replied, "OK. What about 'Jones'?" Indiana was the name of Lucas' Alaskan Malamute, whose habit of riding in the passenger seat as Lucas drove was also the inspiration for Star Wars' Chewbacca.[10] Spielberg was at first reluctant to sign on, as Lucas had told him that he would want Spielberg for an entire trilogy, and Spielberg did not want to work on two more scripts. Lucas told him, however, that he already had the next two movies written, so Spielberg agreed. But when the time came for the first sequel, it was revealed that Lucas had nothing written for either sequel.[10]

The following year, Lucas focused on developing Raiders and the Star Wars sequel The Empire Strikes Back, during which Lawrence Kasdan and Frank Marshall joined the project as screenwriter and producer respectively. Between January 23–27, 1978, for nine hours a day, Lucas, Kasdan, and Spielberg discussed the story and visual ideas. Spielberg came up with Jones being chased by a boulder,[10] which was inspired by Carl Barks' Uncle Scrooge comic "The Seven Cities of Cibola". Lucas later acknowledged that the idea for the idol mechanism in the opening scene and deadly traps later in the film were inspired by several Uncle Scrooge comics.[26] Lucas came up with a submarine, a monkey giving the Hitler salute, and Marion Ravenwood punching Jones in Nepal.[25] Kasdan used a 100-page transcript of their conversations for his first script draft,[27] which he worked on for six months.[10] Ultimately, some of their ideas were too grand and had to be cut: a mine chase,[28] an escape in Shanghai using a rolling gong as a shield,[29] and a jump from an airplane in a raft, all of which made it into the prequel, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.[10]

Spielberg and Lucas disagreed on the character: although Spielberg saw him as a Bondian playboy, Lucas felt the character's academic and adventurer elements made him complex enough. Spielberg had a darker vision of Jones, interpreting him as an alcoholic similar to Humphrey Bogart's character Fred C. Dobbs in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). This characterization fell away during the later drafts, though elements survive in Jones's reaction when he believes Marion to be dead.[25] Costume designer Deborah Nadoolman credits Secret of the Incas (1954), starring Charlton Heston as Harry Steele, as an influence on the development of the character, noting that the crew watched the film together several times.

Initially, the film was rejected by every major studio in Hollywood, mostly due to the $20 million budget and the deal Lucas was offering.[30] Eventually Paramount agreed to finance the film, with Lucas negotiating a five-picture deal. By April 1980, Kasdan's fifth draft was produced, and production was getting ready to shoot at Elstree Studios, with Lucas trying to keep costs down.[13] With four illustrators, Raiders of the Lost Ark was Spielberg's most storyboarded film of his career to date, further helping the film economically. He and Lucas agreed on a tight schedule to keep costs down and to follow the "quick and dirty" feel of the old Saturday matinée serials. Special effects were done using puppets, miniature models, animation, and camera trickery.[10] According to Spielberg, "We didn't do 30 or 40 takes; usually only four. It was like silent film—shoot only what you need, no waste. Had I had more time and money, it would have turned out a pretentious movie."[31]

Filming

Principal photography began on June 23, 1980, at La Rochelle, France, with scenes involving the Nazi submarine,[13] which had been rented from the production of Das Boot. The U-boat pen was a real one from World War II.[10] The crew moved to Elstree Studios[13] for the Well of Souls scenes, the opening sequence temple interiors and Marion Ravenwood's bar.[32] The Well of Souls scene required 7,000 snakes. The only venomous snakes were the cobras, but one crew member was bitten on set by a python.[10] The bulk of the snakes' numbers were made up with giant but harmless legless lizards known as sheltopusiks (Pseudopus apodus) which occur from the Balkan Peninsula of southeastern Europe to Central Asia. Growing to 1.3 m they are the largest legless lizards in the world and are often mistaken for snakes despite some very obvious differences such as the presence of eyelids and external ear openings, which are both absent from all snakes, and a notched rather than forked tongue. In the finished film, during the scene in which Indiana comes face-to-face with the cobra, a reflection in the glass screen that protected Ford from the snake was seen,[10] an issue that was corrected in the 2003 digitally enhanced re-release. Unlike Indiana, neither Ford nor Spielberg has a fear of snakes, but Spielberg said that seeing all the snakes on the set writhing around made him "want to puke".[10]

All the opening scenes set in the Peruvian jungle were filmed on the Hawaiian island of Kauai (to which Spielberg would return for Jurassic Park). The first shot uses a westerly view of Kalalea Mountain in Anahola, Hawaii.[33] The "temple" location is on the Huleia Stream, part of the privately owned Kipu Ranch, southwest of Lihue, the island's main town. As a working cattle ranch, Kipu is not generally open to the public.[34] The large spiders encountered by Harrison Ford and Alfred Molina are actually a harmless Mexican species of tarantulas (Brachypelma: a species which are commonly kept as exotic pets). A fiberglass boulder 22 feet (7 m) in diameter was made for the scene where Indiana escapes from the temple; Spielberg was so impressed by production designer Norman Reynolds' realization of his idea that he gave the boulder a more prominent role in the film and told Reynolds to let the boulder roll another 15 metres (50 ft).[35] The flying wing shown in the desert fight scene was a fictional model, designed by Reynolds, and Ron Cobb,[36] and custom built by Vickers.[37][38]

The scenes set in Egypt were filmed in Tunisia, and the canyon where Indiana threatens to blow up the Ark was shot in Sidi Bouhlel, just outside Tozeur.[39] The canyon location had been used for the Tatooine scenes from 1977's Star Wars (many of the location crew members were the same for both films[10]) where R2-D2 was attacked by Jawas.[10] The Tanis scenes were filmed in nearby Sedala, a harsh place due to heat and disease. Several cast and crew members fell ill and Rhys-Davies defecated in his costume during one shot.[10] Spielberg averted disease by eating only canned foods from England, but did not like the area and quickly condensed the scheduled six-week shoot to four-and-a-half weeks. Much was improvised: the scene where Marion puts on her dress and attempts to leave Belloq's tent was improvised as was the entire plane fight. During that scene's shooting, a wheel went over Ford's knee and tore his left leg's cruciate ligament, but he refused local medical help and simply put ice on it.[10]

The fight scenes in the town were filmed in Kairouan, while Ford was suffering from dysentery. Stuntman Terry Richards had practiced for weeks with his sword to create the scripted fight scene, choreographing a fight between the swordsman and Jones' whip.[40] However, after filming the initial shots of the scene, after lunch due to Ford's dysentery, Ford and Spielberg agreed to cut the scene down to a gunshot, with Ford saying to Spielberg "Let's just shoot the sucker".[41] It was later voted in at No.5 on Playboy magazine's list of best all time scenes.[40][42] Most of the truck chase was shot by second unit director Michael D. Moore following Spielberg's storyboards, including Indiana being dragged by the truck (performed by stuntman Terry Leonard), in tribute to a famous Yakima Canutt stunt. Spielberg then filmed all the shots with Ford himself in and around the truck cab.[10] Lucas directed a few other second unit shots, in particular the monkey giving the Nazi salute.[31]

The interior staircase set in Washington, D.C. was filmed in San Francisco's City Hall. The University of the Pacific's campus in Stockton, California, stood in for the exterior of the college where Jones works, while his classroom and the hall where he meets the American intelligence agents was filmed at the Royal Masonic School for Girls in Rickmansworth, Hertfordshire, England, which was again used in The Last Crusade. His home exteriors were filmed in San Rafael, California.[32] Opening sequence exteriors were filmed in Kauai, Hawaii, with Spielberg wrapping in September in 73 days, finishing under schedule in contrast to his previous film, 1941.[13][25] The Washington, D.C. coda, although it appeared in the script's early drafts, was not included in early edits but was added later when it was realized that there was no resolution to Jones' relationship with Marion.[43] Shots of the Douglas DC-3 Jones flies on to Nepal were taken from Lost Horizon, and a street scene was from a shot in The Hindenburg.[31] Filming of Jones boarding a Boeing Clipper flying-boat was complicated by the lack of a surviving aircraft. Eventually, a post-war British Short Solent flying-boat formerly owned by Howard Hughes was located in California and substituted.[44]

After viewing the film's rough cut, Lucas's then-wife and frequent collaborator Marcia Lucas opined that there was no emotional closure, because Marion did not appear at the ending. Although Marcia is not credited in the film, her suggestion led to Spielberg reshooting the final exterior sequence on the steps of San Francisco City Hall, which Karen Allen called Indy and Marion's "Casablanca moment".[45][46] The final scene, where the Ark is placed in a vast warehouse, was Spielberg's homage to Citizen Kane, in which the main character's prized childhood sled, "Rosebud", is similarly treated.[47][lower-alpha 1]

Visual effects and sound design

The special visual effects for Raiders were provided by Industrial Light & Magic and include: a matte shot to establish the Pan Am flying boat in the water[49] and miniature work to show the plane taking off and flying, superimposed over a map; animation effects for the beam in the Tanis map room; and a miniature car and passengers[50] superimposed over a matte painting for a shot of a Nazi car being forced off a cliff. The bulk of effects shots were featured in the climactic sequence wherein the Ark of the Covenant is opened and God's wrath is unleashed. This sequence featured animation, a woman to portray a beautiful spirit's face, rod puppet spirits moved through water to convey a sense of floating,[51] a matte painting of the island, and cloud tank effects to portray clouds. The melting of Toht's head was done by exposing a gelatine and plaster model of Ronald Lacey's head to a heat lamp with an under-cranked camera, while Dietrich's crushed head was a hollow model from which air was withdrawn. When the film was originally submitted to the Motion Picture Association of America, it received an R rating because of the scene in which Belloq's head explodes. The filmmakers were able to receive a PG rating when they added a veil of fire over the exploding head scene. (The PG-13 rating was not created until 1984.)[20] The firestorm that cleanses the canyon at the finish was a miniature canyon filmed upside down.[51] Brian Muir and Keith Short created the Ark prop based on the paintings of James Tissot.[52]

Ben Burtt, the sound effects supervisor, made extensive use of traditional foley work in yet another of the production's throwbacks to days of the Republic serials. He selected a .30-30 Winchester rifle for the sound of Jones' pistol. Sound effects artists struck leather jackets and baseball gloves with a baseball bat to create a variety of punching noises and body blows. For the snakes in the Well of Souls sequence, fingers running through cheese casserole and sponges sliding over concrete were used for the slithering noises. The sliding lid on a toilet cistern provided the sound for the opening of the Ark, and the sound of the boulder in the opening is a car rolling down a gravel driveway in neutral. Burtt also used, as he did in many of his films, the ubiquitous Wilhelm scream when a Nazi falls from a truck. In addition to his use of such time-honored foley work, Burtt also demonstrated the modern expertise honed during his award-winning work on Star Wars. He employed a synthesizer for the sounds of the Ark, and mixed dolphins' and sea lions' screams for those of the spirits within.[53] Michael Pangrazio created the final shot's matte painting on glass over three months.[54]

Music

John Williams composed the score for Raiders of the Lost Ark, which was the only score in the series performed by the London Symphony Orchestra, the same orchestra that performed the scores for the Star Wars saga. The score most notably features the well-known "Raiders March". This piece came to symbolize Indiana Jones and was later used in the scores for the other three films. Williams originally wrote two different candidates for Jones's theme, but Spielberg enjoyed them so much that he insisted that both be used together in what became the "Raiders March".[55] The alternately eerie and apocalyptic theme for the Ark of the Covenant is also heard frequently in the score, with a more romantic melody representing Marion and, more broadly, her relationship with Jones. The score as a whole received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Score, but lost to the score to Chariots of Fire composed by Vangelis.

Release

Merchandise

The only video game based exclusively on the film is Raiders of the Lost Ark, released in 1982 by Atari for their Atari 2600 console.[56] The first third of the video game Indiana Jones' Greatest Adventures, released in 1994 by JVC for Nintendo's Super Nintendo Entertainment System, is based entirely on the film. Several of the film's sequences are reproduced (the boulder run and the showdown with the Cairo Swordsman among them); however, several inconsistencies with the film are present in the game, such as Nazi soldiers and bats being present in the Well of Souls sequence, for example.[57] The game was developed by LucasArts and Factor 5. In the 1999 game Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine, a bonus level brings Jones back to the Peruvian temple of the film's opening scene.[58] In 2008, to coincide with the release of Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Lego released the Lego Indiana Jones line—which included building sets based on Raiders of the Lost Ark[59]—and LucasArts published a video game based on the toyline, Lego Indiana Jones: The Original Adventures, which was developed by Traveller's Tales.[60]

Marvel Comics published a comic book adaptation of the film by writer Walt Simonson and artists John Buscema and Klaus Janson. It was published as Marvel Super Special #18[61] and as a three-issue limited series.[62] This was followed with the comic book series The Further Adventures of Indiana Jones which was published monthly from January 1983 through March 1986.

In 1981, Kenner released a 30-centimetre (12 in) doll of Indiana Jones, and the following year they released nine action figures of the film's characters, three playsets, as well as toys of the Nazi truck and Jones' horse. They also released a board game. In 1984, miniature metal versions of the characters were released for a role playing game, The Adventures of Indiana Jones, and in 1995 Micro Machines released die-cast toys of the film's vehicles.[63] Hasbro released action figures based on the film, ranging from 3 to 12 inches (7.6 to 30.5 cm), to coincide with Kingdom of the Crystal Skull on May 1, 2008.[64] Later in 2008, and in 2011, two high-end sixth scale (1:6) collectible action figures were released by Sideshow Collectibles, and Hot Toys, Ltd. respectively. A novelization by Ryder Windham was released in April 2008 by Scholastic to tie in with the release of Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. A previous novelization by Scottish author Campbell Armstrong (under the pseudonym Campbell Black) was concurrently released with the film in 1981. A book about the making of the film was also released, written by Derek Taylor.

Home media

The film was released on VHS, Betamax and VideoDisc in pan and scan only, and on laserdisc in both pan and scan and widescreen.

The initial release of Raiders on VHS shipped 425,000 units at $39.95 in the United States on its first day of release, a then record.[65] The film was the first to sell over a million units worldwide with sales revenue of $25 million.[66]

For its 1999 VHS re-issue, the film was remastered in THX and made available in widescreen. The outer package was labeled Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark for consistency with the film's prequel and its sequel. The subsequent DVD release in 2003 features this title as well. The title in the film itself remains unchanged, even in the restored DVD print. In the DVD, two subtle digital revisions were added. First, a connecting rod from the giant boulder to an offscreen guidance track in the opening scene was removed from behind the running Harrison Ford; second, a reflection in the glass partition separating Ford from the cobra in the Well of Souls was removed.[67] Shortly before the theatrical release of Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Raiders (along with The Temple of Doom and The Last Crusade) was re-released on DVD with additional extra features not included on the previous set on May 13, 2008. The film was released on Blu-ray Disc in September 2012.[68] Previously, only Kingdom of the Crystal Skull had been available on Blu-ray.

Reception

Box office

Raiders of the Lost Ark, made on a $20 million budget,[2] grossed $384 million worldwide throughout its theatrical releases.

The film opened at number one in the United States, grossing $8,305,823 from 1,078 theaters during its opening weekend,[69] which caused concern for Paramount executives as they were expecting a bigger weekend and needed the film to be one of the highest-grossing films of all-time to be profitable for them[70] due to the deal that Lucasfilm had made with Paramount.[71] The film was knocked off the number one slot the following week by Superman II's record $14.1 million opening weekend and it remained behind Superman II for the next three weekends but was narrowing the gap each weekend and after adding a further 22 theaters to 1,100, returned to number one in its sixth weekend taking its gross to $79 million.[71] After 111 days of release it had grossed $135 million surpassing Grease as Paramount Pictures' highest-grossing film at that time,[72] and went on to gross $212 million in its initial release in the United States and Canada[3] making it by some distance the highest-grossing film of 1981.[73] Box Office Mojo estimates that the film sold more than 70 million tickets in the US in its initial theatrical run.[74]

It remains one of the top twenty-five highest-grossing films ever made when adjusted for inflation.[75] Its IMAX release in 2012 opened at number 14 and grossed $1,673,731 from 267 theaters ($6,269 theater average) during its opening weekend. In total, the IMAX release grossed $3,125,613 domestically.[76]

Critical reception

At the time of its release Raiders of the Lost Ark was highly acclaimed by critics and audiences alike.

In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby praised the film, calling it, "one of the most deliriously funny, ingenious and stylish American adventure movies ever made."[77] Roger Ebert in his review for the Chicago Sun-Times wrote,

"Two things, however, make Raiders of the Lost Ark more than just a technological triumph: its sense of humor and the droll style of its characters [...] We find ourselves laughing in surprise, in relief, in incredulity at the movie's ability to pile one incident upon another in an inexhaustible series of inventions."[78]

Ebert later added it to his list of "Great Movies".[79] Rolling Stone said the film was "the ultimate Saturday action matinee–a film so funny and exciting it can be enjoyed any day of the week."[80] Bruce Williamson of Playboy claimed: "There's more excitement in the first ten minutes of Raiders than any movie I have seen all year. By the time the explosive misadventures end, any movie-goer worth his salt ought to be exhausted."[81] Stephen Klain of Variety also praised the film. Yet, making an observation that would revisit the franchise with its next film, he felt that the film was surprisingly violent and bloody for a PG-rated film.[82] Christopher John reviewed Raiders of the Lost Ark in Ares Magazine #9 and commented that

"The film is as devoid of profound messages as was Star Wars. It is basically "good versus evil" with little else except action that is fast paced and exciting. The sets are exotic, the special effects are as expected – many, varied and first class. The leading lady (Karen Allen) is beautiful; the music by John Williams is spectacular, and the sum of the parts is one thoroughly enjoyable summer picture for just about everyone."[83]

There were some dissenting voices: Sight & Sound described it as an "expensively gift-wrapped Saturday afternoon pot-boiler",[84] and New Hollywood champion Pauline Kael, who once contended that she only got "really rough" on large films that were destined to be hits but were nonetheless "atrocious",[85] found the film to be a "machine-tooled adventure" from a pair of creators who "think just like the marketing division".[86] (Lucas later named a villain, played by Raiders Nazi strongman Pat Roach, in his 1988 fantasy film Willow after Kael.)[85]

The film remains well-regarded. On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 95% "Certified Fresh" rating based on 79 reviews, with an average rating of 9.26/10. The site's critical consensus stating: "Featuring bravura set pieces, sly humor, and white-knuckle action, Raiders of the Lost Ark is one of the most consummately entertaining adventure pictures of all time."[87] The film also has an 85 rating on Metacritic, indicating "universal acclaim".[88]

Awards and accolades

The film was subsequently nominated for nine Academy Awards, including Best Picture, in 1982 and won four (Best Sound, Best Film Editing, Best Visual Effects, and Best Art Direction-Set Decoration (Norman Reynolds, Leslie Dilley, and Michael D. Ford)). It also received a Special Achievement Award for Sound Effects Editing. It won numerous other awards, including a Grammy Award and Best Picture at the People's Choice Awards. Spielberg was also nominated for a Golden Globe Award.[89]

- American Film Institute

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies—No. 60

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills—No. 10

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Indiana Jones—No. 2 Hero

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "Snakes! Why did it have to be snakes?"—Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores—Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)—No. 66

Influence

Following the success of Raiders, a prequel, The Temple of Doom, and two sequels, The Last Crusade and Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, were produced, with a third sequel set for release in 2021.[93] A TV series, entitled The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, was also spun off from this film, and details the character's early years. Numerous other books, comics, and video games have also been produced.

In 1998, the American Film Institute placed the film at #60 on its top 100 films of the first century of cinema. In 2007, AFI updated the list and placed it at #66. They also named it as the 10th most thrilling film, and named Indiana Jones as the second greatest hero. In 1999, the film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the U.S. Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. Indiana Jones has become an icon, being listed as Entertainment Weekly's third favorite action hero, while noting "some of the greatest action scenes ever filmed are strung together like pearls" in this film.[94]

An amateur, near shot-for-shot remake was made by Chris Strompolos, Eric Zala, and Jayson Lamb, then children in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. It took the boys 7 years to finish, from 1982 to 1989. After production of the film, called Raiders of the Lost Ark: The Adaptation, it was shelved and forgotten until 2003, when it was discovered by Eli Roth[95][96] and acclaimed by Spielberg himself, who congratulated the boys on their hard work and said he looked forward to seeing their names on the big screen.[97] Scott Rudin and Paramount Pictures purchased the trio's life rights with the goal of producing a film based on their adventures making their remake.[98][99]

In 2014, film director Steven Soderbergh published an experimental black-and-white version of the film, with the original soundtrack and dialogue replaced by an electronic soundtrack. Soderbergh said his intention was to encourage viewers to focus on Spielberg's extraordinary staging and editing: "This filmmaker forgot more about staging by the time he made his first feature than I know to this day."[100]

Assessing the film's legacy in 1997, Bernard Weinraub, film critic for The New York Times, which had initially reviewed the film as "deliriously funny, ingenious, and stylish,"[101] maintained that "the decline in the traditional family G-rated film, for 'general' audiences, probably began" with the appearance of Raiders of the Lost Ark. "Whether by accident or design," found Weinraub, "the filmmakers made a comic nonstop action film intended mostly for adults but also for children."[102] 8 years later, in 2005, viewers of Channel 4 rated the film as the 20th-best family film of all time, with Spielberg taking best over-all director honors.[103]

On Empire magazine's list of the 500 Greatest Movies of All Time, Raiders ranked second, beaten only by The Godfather.[104] The film was ranked at #11 in a list of the 25 best action and war films of all time by The Guardian.[105][106][107]

In conjunction with the Blu-ray release, a limited one-week release in IMAX theaters was announced for September 7, 2012. Steven Spielberg and sound designer Ben Burtt supervised the format conversion. No special effects or other visual elements were altered, but the audio was enhanced for surround sound.[108]

In The Big Bang Theory episode "The 21-Second Exitation," the protagonists are slightly late to see a 21-seconds-expanded version of Raiders of the Lost Ark (which, as Leonard suggests, could include the cut sequence in which Jones entered the U-boat), and an enraged Sheldon steals the film reels, followed by dozens of fans trying to stop him and comments about the similarity of the situation to the beginning of the film, when Jones runs away from the Hovitos to the hydroplane. Furthermore, in the episode "The Raiders Minimization", Amy "ruins" the film for Sheldon by pointing out that Indiana Jones is mostly irrelevant to the plot: in his absence, the Nazis would still have found the Ark with the exact same outcome. Indiana's only contribution is to prevent a second Nazi expedition from retrieving it.

2012 replica mystery

In December 2012, the University of Chicago's admissions department received a package in the mail addressed to Henry Walton Jones, Jr., Indiana Jones' full name. The address on the stamped package was listed for a hall that was the former home of the university's geology and geography department. Inside the manila envelope was a detailed replica journal similar to the one Jones used in the movie, as well as postcards and pictures of Marion Ravenwood. The admissions department posted pictures of the contents on its Internet blog, looking for any information about the package. It was discovered that the package was part of a set to be shipped from Guam to Italy that had been sold on eBay. The package with the journal had fallen out in transit and a postal worker had sent it to the university, as it had a complete address and postage, which turned out to be fake. All contents were from a Guam "prop replicator" who sells them all over the world. The university will display its replica in the main lobby of the Oriental Institute.[109]

References

Footnotes

Citations

- "Raiders of the Lost Ark (A)". British Board of Film Classification. June 2, 1981. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- Lawrence O’Toole (June 22, 1981). "A long, cool summer of Saturday afternoons", Maclean's. Retrieved on May 18, 2020.

- "Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2007.

- "Back to the Future – Hollywood's 100 Favorite Films". Archived from the original on January 18, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- "100 Best Movies of All Time by Mr. Showbiz". filmsite.org. Archived from the original on June 18, 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- "The 100 Greatest Movies". Empire. Archived from the original on November 29, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies". afi.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- Bohnen, Michael J. (February 22, 2016). "Why Indiana Jones' Nazi-Loving Enemy Said a Torah Prayer". jta.org. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Indiana Jones: Making the Trilogy (DVD). Paramount Pictures. 2003.

- Knolle, Sharon (June 12, 2011). "30 Things You Might Not Know About 'Raiders of the Lost Ark'". Moviefone. Archived from the original on August 2, 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- "Facts and trivia of the Lost Ark". Lucasfilm. October 14, 2003. Archived from the original on May 18, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- Hearn, pp. 127–134

- Gregory Kirschling, Jeff Labrecque (March 12, 2008). "Indiana Jones: 15 Fun Facts". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on March 15, 2008. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- "The People Who Were Almost Cast". Empire Online. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- Polanski, Roman; Cronin, Paul (January 1, 2005). "Roman Polanski: Interviews". University Press of Mississippi. Retrieved December 22, 2016 – via Google Books.

- Glenn Whipp (May 22, 2008). "Keeping up with Jones". Halifax Chronicle-Herald. Archived from the original on March 9, 2009. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- Kinski, Klaus (1996). Kinski Uncut. Translated by Joachim Neugröschel. London: Bloomsbury. p. 294. ISBN 0-7475-2978-7.

- The Stunts of Indiana Jones (DVD). Paramount Pictures. 2003.

- The Light and Magic of Indiana Jones (DVD). Paramount Pictures. 2003.

- Marcus Hearn (2005). The Cinema of George Lucas. New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc, Publishers. p. 80. ISBN 0-8109-4968-7.

- Hearn, pp.112–115

- "Know Your MacGuffins". Empire. April 23, 2008. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- Jim Windolf (December 2, 2007). "Q&A: Steven Spielberg". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on February 19, 2012. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- McBride, Joseph (1997). "Rehab". Steven Spielberg. New York City: Faber and Faber. pp. 309–322. ISBN 0-571-19177-0.

- E. Summer, Walt Disney's Uncle $crooge McDuck: His Life and Times by Carl Barks, Celestial Arts ed., 1981; T. Andrae, Carl Barks and the Art of the Disney Comic Book, Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2006.

- Hearn, p.122–123

- Script 3rd Draft Archived April 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, scene 45-47

- Script 3rd Draft Archived April 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, scene 148–155

- "Raiders Of The Lost Ark: An Oral History". Empire. April 24, 2008. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- Schickel, Richard (June 15, 1981). "Cinema: Slam! Bang! A Movie Movie". Time. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- Fromter, Marco (August 18, 2006). "Around the World with Indiana Jones". Lucasfilm. Archived from the original on February 7, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- "Hokualele Rd, Anahola, Hawaii". Google Maps. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- "Worldwide guide to movie locations". Movie-locations.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- Norman Reynolds (Production Designer). Making the Trilogy (DVD). Event occurs at 17:40.

Steven said 'Why don't we make it another 50ft longer?' Which of course we did

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved July 3, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- IndyGear Props Section — Planes

- Peter Garrison (April 26, 2016). "Technicalities: The Story Behind the German Airplane in Raiders of the Lost Ark". Flying Magazine. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- Taylor, Derek (1981). The Making of Raiders of The Lost Ark. Ballantine Books.

- "Indiana Jones Stuntman Terry Richards Interview". Red Carpet News. 2012. Archived from the original on June 26, 2014. Retrieved June 24, 2014.

- "The Urban Legends of Indiana Jones". Lucasfilm. January 13, 2004. Archived from the original on June 12, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- Hayward, Anthony (July 9, 2014). "Terry Richards: Stuntman who battled four James Bonds, Luke Skywalker and Rambo and was famously shot dead by Indiana Jones". The Independent. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- "Twenty-Five Reasons to Watch Raiders Again". Lucasfilm. June 12, 2006. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- "Oakland Aviation Museum". Archived from the original on November 12, 2010. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- "3 ways in which Marcia Lucas helped save Star Wars". SYFY UK. 2017. Archived from the original on May 26, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- Jones, Brian Jay (2016). George Lucas: A Life. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. p. 297. ISBN 978-0316257442.

- McGee, Scott (August 12, 2011). "Citizen Kane (1941)". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on October 17, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

Director Steven Spielberg paid homage to the famous ending of Citizen Kane with the epilogue to Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). ... buried in a vast warehouse, much like the fate of "Rosebud" ...

- Singer, Matt (May 22, 2018). "Was the World Wrong About Kingdom of the Crystal Skull?". ScreenCrush. Archived from the original on October 28, 2019. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- Smith, Thomas G. Industrial Light & Magic: The Art of Special Effects. p. 140. 1986

- Smith, Thomas G. Industrial Light & Magic: The Art of Special Effects. p. 66. 1986

- Smith, Thomas G. Industrial Light & Magic: The Art of Special Effects. p. 62. 1986

- Marshall, Nancy Rose and Malcolm Warner (1999) James Tissot: Victorian Life, Modern Love

- The Sound of Indiana Jones (DVD). Paramount Pictures. 2003.

- Nedomansky, Vashi (May 6, 2014). "Raiders of the Lost Ark – Matte Painting". VashiVisuals. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- John Williams (2003). The Music of Indiana Jones (DVD). Paramount Pictures.

- Buchanan, Levi (May 20, 2008). "Top 10 Indiana Jones Games". IGN. Archived from the original on May 27, 2008. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- Buchanan, Levi (November 24, 2009). "Indiana Jones' Greatest Adventures Review". IGN. Archived from the original on January 21, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- "Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine – PC Preview". IGN. November 2, 1999. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- "LEGO Group Secures Exclusive Construction Category Rights to Indiana Jones(TM) Property" (Press release). The LEGO Group. 2007. Archived from the original on September 5, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- "Lego Indiana Jones: The Original Adventures Company Line". GameSpot. April 11, 2008. Archived from the original on March 28, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- "GCD :: Issue :: Marvel Super Special #18". comics.org. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- Raiders of the Lost Ark Archived March 23, 2014, at the Wayback Machine at the Grand Comics Database.

- "The Adventures of Indiana Jones". Cool Toy Review. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- Edward Douglas (February 16, 2008). "Hasbro Previews G.I. Joe, Hulk, Iron Man, Indy & Clone Wars". SuperHeroHype.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Bierbaum, Tom (May 3, 1985). "'Star Trek III,' Richie Vid Head February Sales". Variety. p. 26.

- Bierbaum, Tom (December 5, 1984). "'Raiders' Tapes Over a Million Worldwide". Variety. p. 26.

- Miss Cellania (May 21, 2008). "10 Awesome Indiana Jones Facts". Mental floss. Archived from the original on May 25, 2008. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- "Own it on Blu-ray & Digital Download Tuesday, September 18". Lucasfilm. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- "Raiders of the Lost Ark". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- "Weekend Biz Breaks B.O. Logjam; 'Raiders,' 'Titans' and 'History' Score". Variety. June 17, 1981. p. 3.

- Ginsberg, Steven (July 27, 1981). "'Superman,' 'Raiders' Neck & Neck". Daily Variety. p. 1.

- "'Ark' Tops 'Grease'". Variety. October 7, 1981. p. 6.

- "1981 Domestic Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 1, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 4, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- "Box Office Mojo Alltime Adjusted". Archived from the original on January 24, 2018. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "Raiders of the Lost Ark (IMAX) (2012)". Box Office Mojo. October 4, 2012. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- Canby, Vincent (June 12, 1981). "Raiders of the Lost Ark". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 22, 2018. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1981). "Raiders of the Lost Ark". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on May 28, 2007. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- Roger Ebert (April 30, 2000). "Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on April 30, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- Sragow, Michael (June 25, 1981). "Inside 'Raiders of the Lost Ark'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

Raiders of the Lost Ark, the new nonstop adventure directed by Steven Spielberg for George Lucas' film company, Lucasfilms Ltd., is the ultimate Saturday action matinee – a film so funny and exciting it can be enjoyed any day of the week. Every bit of it is "good parts."

- Michael G. Ryan. "Raiders of the Lost Ark 20th Anniversary". Star Wars Insider. July/August 2001.

- Klain, Stephen (June 5, 1981). "Raiders of the Lost Ark". Variety. Archived from the original on February 16, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- John, Christopher (July 1981). "Film & Television". Ares Magazine. Simulations Publications, Inc. (9): 20.

- "On Now". Sight & Sound (Autumn ed.). British Film Institute (BFI). 50 (4): 288. 1981.

- Van Gelder, Lawrence (September 4, 2001). "Pauline Kael, Provocative and Widely Imitated New Yorker Film Critic, Dies at 82". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 31, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- Kael, Pauline (June 15, 1981). "Whipped". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on September 9, 2014. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "Raiders of the Lost Ark". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- "Raiders of the Lost Ark". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 18, 2015. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- Tom O'Neil (May 8, 2008). "Will 'Indiana Jones,' Steven Spielberg and Harrison Ford come swashbuckling back into the awards fight?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- "The 54th Academy Awards (1982) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- "The 39th Annual Golden Globe Awards (1982)". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2011.

- Galvan, Manuel (September 7, 1982). "Science-fiction awards given to out-of-this-world writers". Chicago Tribune. p. 16. Archived from the original on June 19, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- Chitwood, Adam (April 25, 2017). "'Indiana Jones 5' Delayed a Year; Disney Shifts 'Wreck-It Ralph 2', 'Gigantic' and More". Collider. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Marc Bernadin (October 23, 2007). "25 Awesome Action Heroes". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 30, 2007. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- Harry Knowles (May 31, 2003). "Raiders of the Lost Ark shot-for-shot teenage remake review!!!". Ain't It Cool News. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- Jim Windolf. "Raiders of the Lost Backyard". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on May 9, 2009. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- Sarah Hepola (May 30, 2003). "Lost Ark Resurrected". Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 26, 2006. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- Harry Knowles (February 26, 2004). "Sometimes, The Good Guys Win!!! Raiders of the Lost Ark shot for shot filmmakers' life to be MOVIE!!!". Ain't It Cool News. Archived from the original on July 12, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- Dave McNary (February 25, 2004). "Rudin's on an 'Ark' lark". Variety. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- "Raiders". Extension765.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2014. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- Vincent Canby (June 12, 1981). "Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 12, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- Bernard Weinraub (July 22, 1997). "Movies for Children, and Their Parents, Are Far From 'Pollyanna'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "ET Crowned 'Greatest Family Film'". BBC News Online. December 23, 2005. Archived from the original on December 22, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "Empire 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- Heritage, Stuart (October 19, 2010). "Raiders of the Lost Ark: No 11 best action and war film of all time". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- Robey, Tim; Collin, Robbie (September 21, 2017). "Beat it, Kingsman: the 24 greatest action movies of all time". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- "The 500 Greatest Movies Of All Time, Feature | Movies – Empire". gb: Empireonline.com. December 11, 2015. Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- Itzkoff, Dave (August 14, 2012). "That's a Big Boulder, Indy: Steven Spielberg on the Imax Rerelease of 'Raiders of the Lost Ark'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 16, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- Watercutter, Angela (December 17, 2012). "Mystery of the Indiana Jones Journal Solved: It Came From the Internet. And Guam". Wired. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

Further reading

- Black, Campbell (September 1987). Raiders of the Lost Ark. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-35375-7.

- Kasdan, Lawrence (1981). Raiders of the Lost Ark: The Illustrated Screenplay. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-30327-X.

- Taylor, Derek (August 1981). The Making of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-29725-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Raiders of the Lost Ark. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Raiders of the Lost Ark |

- IndianaJones.com, Lucasfilm's official Indiana Jones site, later replace with Facebook

- Raiders of the Lost Ark at Lucasfilm.com

- Raiders of the Lost Ark on IMDb

- Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Raiders of the Lost Ark at the TCM Movie Database

- Raiders of the Lost Ark at Box Office Mojo

- Raiders of the Lost Ark at Rotten Tomatoes

- Raiders of the Lost Ark at Metacritic

- Raiders of the Lost Ark on YouTube