Jacob Lawrence

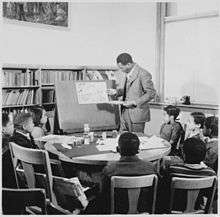

Jacob Armstead Lawrence (September 7, 1917 – June 9, 2000) was an American painter known for his portrayal of African-American life. As well as a painter, storyteller, and interpreter, he was an educator. Lawrence referred to his style as "dynamic cubism", though by his own account the primary influence was not so much French art as the shapes and colors of Harlem.[1] He brought the African-American experience to life using blacks and browns juxtaposed with vivid colors. He also taught and spent 16 years as a professor at the University of Washington.[2]

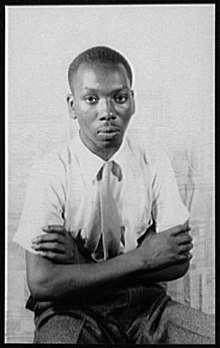

Jacob Lawrence | |

|---|---|

Jacob Lawrence in 1941 | |

| Born | September 7, 1917 |

| Died | June 9, 2000 (aged 82) Seattle, Washington |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Harlem Community Art Center |

| Known for | Paintings portraying African-American life |

Notable work | Migration Series |

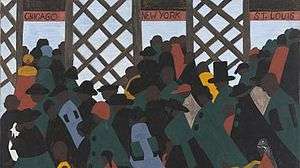

Lawrence is among the best-known 20th-century African-American painters. He was 23 years old when he gained national recognition with his 60-panel Migration Series,[3] painted on cardboard. The series depicted the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North. A part of this series was featured in a 1941 issue of Fortune. The collection is now held by two museums: the odd-numbered paintings are on exhibit in the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., and the even-numbered are on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Lawrence's works are in the permanent collections of numerous museums, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, MoMA, the Whitney Museum, the Phillips Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, Reynolda House Museum of American Art, and the Museum of Northwest Art. He is widely known for his modernist illustrations of everyday life as well as epic narratives of African-American history and historical figures.[2]

Life

Jacob Lawrence was born September 7, 1917, in Atlantic City, New Jersey. His parents moved him and his siblings from the rural south, and then divorced in 1924.[4] His mother put him and his two younger siblings into foster care in Philadelphia. When he was 13, he and his siblings moved to New York City, where he reconnected with his mother in Harlem. Lawrence was introduced to art shortly after that when their mother enrolled him in after school classes at an arts and crafts settlement house in Harlem, called Utopia Children's Center, in an effort to keep him busy. The young Lawrence often drew patterns with crayons. In the beginning, he copied the patterns of his mother's carpets. One of his art teachers noted great potential in Lawrence.

After dropping out of school at 16, Lawrence worked in a laundromat and a printing plant. He continued with art, attending classes at the Harlem Art Workshop, taught by the noted African-American artist Charles Alston. Alston urged him to attend the Harlem Community Art Center, led by the sculptor Augusta Savage. Savage secured Lawrence a scholarship to the American Artists School and a paid position with the Works Progress Administration, established during the Great Depression by the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Lawrence continued his studies as well, working with Alston and Henry Bannarn, another Harlem Renaissance artist, in the Alston-Bannarn workshop.

On July 24, 1941, Lawrence married the painter Gwendolyn Knight, also a student of Savage. She supported his work and even helped him with captions for many of his series of paintings.[2] They were married until his death in 2000.

In October 1943, during the Second World War, Lawrence was drafted into the United States Coast Guard and served as a public affairs specialist with the first racially integrated crew on the USCHC Sea Cloud, under Carlton Skinner.[5] He continued to paint and sketch while in the Coast Guard, documenting the experience of war around the world. He produced 48 paintings during this time, all of which have been lost. He achieved the rank of petty officer third class. After the war, he created his famous War Series.[2]

Back in New York, Lawrence continued to paint. He grew depressed, however, and in 1949, he checked himself into Hillside Hospital in Queens, where he stayed for 11 months. He painted as an inpatient. The works he created in hospital differed from his usual artworks because they displayed sadness and agony.[2] Shortly after leaving Hillside, Lawrence turned to theater.

After many years in New York, in 1970 Lawrence and Knight moved to the Pacific Northwest, where he had been invited to be an art professor at the University of Washington. They settled in Seattle. Some of his works are displayed in the university's Meany Hall for the Performing Arts and in the Paul G. Allen Center for Computer Science & Engineering. Lawrence's painting Theater, installed in the main lobby of Meany Hall, was commissioned by the University in 1985 for that space.[6]

Education and career

For Jacob Lawrence's education, he took Works Progress Administration art classes in New York (1934-1937) and he also studied at Harlem Art Workshop in New York in 1937.[7] Harlem provided crucial training for the majority of black artists in the United States. Lawrence was one of the first artists trained in and by the African-American community in Harlem.[8] Throughout his lengthy artistic career, Lawrence concentrated on exploring the history and struggles of African Americans. He often portrayed important periods in African-American history. The artist was 21 years old when his series of paintings of the Haitian general Toussaint L’Ouverture, who led the revolution of the slaves that eventually gained independence, was shown in an exhibit of African-American artists at the Baltimore Museum of Art. This impressive work was followed by a series of paintings of the lives of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, as well as a series of pieces about the abolitionist John Brown. Harlem artist Charles Allston instantly recognized Lawrence’s talent. "The place of Jacob Lawrence among younger painters is unique," Allston said. "Having thus far miraculously escaped the imprint of academic ideas and current vogues in art, to which young artists are most susceptible, he has followed a course of development dictated entirely by his own inner motivations."[9]

Lawrence completed the 60-panel set of narrative paintings entitled Migration of the Negro, now called the Migration Series, in 1940–41. The series was a portrayal of the Great Migration, when hundreds of thousands of African Americans moved from the rural South to the North after World War I and showed their adjusting to Northern cities. It was exhibited in New York at the Museum of Modern Art and brought him national recognition.[10] His early work involved general depictions of everyday life in Harlem and also a major series dedicated to Black History (1940-1941).[7] In the 1940s Lawrence was given his first major solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and became the most celebrated African-American painter in the country. Lawrence taught at Black Mountain College during the 1946 Summer Art Institute, where he was influenced by the teaching of Josef Albers. This is when his form and design changed in his style of realism.[7]

The "hard, bright, brittle" aspects of Harlem during the Great Depression inspired Lawrence as much as the colors, shapes and patterns inside the residents' homes. "Even in my mother's home," Lawrence told historian Paul Karlstrom, "people of my mother's generation would decorate their homes in all sorts of color... so you'd think in terms of Matisse."[11] He used water-based media throughout his career.[7] Lawrence started to gain some notice for his dramatic and lively portrayals of both contemporary scenes of African-American urban life as well as historical events, all of which he depicted in crisp shapes, bright, clear colors, dynamic patterns, and through revealing posture and gestures. However, his mother still hoped he would choose a career in the Civil Service.[4]

Shortly after moving to Washington state, Lawrence did a series of five paintings on the westward journey of African-American pioneer, George Washington Bush. These paintings are now in the collection of the State of Washington History Museum.[12]

Lawrence illustrated several works for children. Harriet and the Promised Land appeared in 1968 and used the series of paintings that told the story of Harriet Tubman.[13] It was listed as one of the year's best illustrated books by the New York Times and praised by the Boston Globe: "The author's artistic talents, sensitivity and insight into the black experience have resulted in a book that actually creates, within the reader, a spiritual experience." Two similar volumes based on his John Brown and Great Migration series followed.[14] Lawrence created illustrations for a selection of 18 of Aesop's Fables for Windmill Press in 1970, and the University of Washington Press published the full set of 23 tales in 1998.[15]

Lawrence taught at several universities including the University of Washington where he was graduate advisor to lithographer and abstract painter James Claussen[16]

In 1999, he and his wife established the Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation for the creation, presentation and study of American art, with a particular emphasis on work by African-American artists.[17] It represents their estates[18] and maintains a searchable archive of nearly a thousand images of their work.[19]

Illness and death

Lawrence continued to paint until a few weeks before his death from lung cancer on June 9, 2000, at the age of 82.[17] The New York Times described him as "One of America's leading modern figurative painters" and "among the most impassioned visual chroniclers of the African-American experience."[17] Shortly before his death he stated: "...for me, a painting should have three things: universality, clarity and strength. Clarity and strength so that it may be aesthetically good. Universality so that it may be understood by all men."[20] His last commissioned public work, the mosaic mural New York in Transit, was installed in October 2001 in the Times Square subway station in New York City.[21]

His wife, Gwendolyn Knight, survived him and died in 2005 at the age of 91.[22]

Special works of art

- And the Migrants Kept Coming and In the North the Negro had Better Educational Facilities series dedicated to black history.

- The 41 pictures of the Toussaint L’Ouverture series (1937-1938) are addressed to Haiti's struggle for independence in the 19th century.[7]

- Harriet Tubman (series), 1938–39

- Frederick Douglass (series), 1939–40

- The Migration Series was shown at the Downtown Gallery in Greenwich Village in 1941.[23] Lawrence became a nationally known figure virtually overnight because of this series.

- John Brown (series), 1941–42

- The Businessmen, 1947

Recognition

- 1941, he was the first African-American artist to be represented in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

- 1970, the NAACP awarded him the Spingarn Medal for his outstanding achievements.

- 1971, he was elected to the National Academy of Design as an Associate member and became a full Academician in 1979.

- 1974, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York held a major retrospective of his work.

- 1983, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

- 1990, he received the U.S. National Medal of Arts.

- 1995, he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[24]

- 1996, the Meadows School of the Arts at Southern Methodist University awarded him the Algur H. Meadows Award for Excellence.[25]

- 1998, Washington State awarded him its highest honor, The Washington Medal of Merit.

His work is in the permanent collections of numerous museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, the Phillips Collection, the Brooklyn Museum, the National Gallery of Art[26] and Reynolda House Museum of American Art. In May 2007, the White House Historical Association (via the White House Acquisition Trust) purchased Lawrence's The Builders (1947) for $2.5 million at auction. The painting hangs in the White House Green Room.[27]

Jacob Lawrence made 319 artworks in his life. The U.S. copyright representative for the Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation is the Artists Rights Society.[28] Major traveling exhibitions of his works have been presented in museums across the country.[29]

Legacy

- Jacob Lawrence retrospective exhibition, Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, February 6 – May 4, 2003, Seattle Art Museum

- The Seattle Art Museum offers the Gwendolyn Knight and Jacob Lawrence Fellowship, a $10,000 award to "individuals whose original work reflects the Lawrences' concern with artistic excellence, education, mentorship and scholarship within the cultural contexts and value systems that informed their work and the work of other artists of color."[30]

- The Jacob Lawrence Gallery at the University of Washington School of Art + Art History + Design offers an annual Jacob Lawrence Legacy Residency.[31]

- Between Form and Content: Perspectives on Jacob Lawrence and Black Mountain College, September 28, 2018 – January 12, 2019, Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center

Institutions that include works by Lawrence in their permanent collections include:

- Art Institute Chicago, Chicago, IL

- Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, Kalamazoo, MI

- Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN

- Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, NY

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

- Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.

- SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, GA

- Seattle Art Museum (SAM), Seattle, WA

- The Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN

- Whitney Museum of American Art, NY, NY

References

- Hughes, Robert, American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America, excerpted online at Jacob Lawrence Archived December 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Artchive.com.

- "Jacob Lawrence". Biography.com. Archived from the original on December 21, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- Migration Series Archived June 13, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Phillips Collection

- "Jacob Lawrence - Bio". Phillips Collection. Archived from the original on May 23, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- "Jacob Lawrence, USCG biography".

- "Meany Hall for the Performing Arts". Meany Center for the Performing Arts, University of Washington. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- Falconer, Morgan. "Lawrence, Jacob | Grove Art". www.oxfordartonline.com.

- "Jacob Lawrence: Exploring Stories". whitney.org. Archived from the original on May 23, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- "Black and White in Color". The Attic. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- www.sbctc.edu. "Module 1: Introduction and Definitions" (PDF). Saylor.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 1, 2012. Retrieved April 2, 2012.

- Challenge of the Modern: African-American Artists 1925-1945. 1. New York, NY: The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York. 2003. ISBN 0-942949-24-2.

- Program for Making a Life | Creating a World, Northwest African American Museum, 2008.

- Kramer, Hilton (November 17, 1968). "For Young Readers". New York Times. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- Porter, Connie (February 13, 1994). "Children's Books; Black History". New York Times. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- "Children's Books; Bookshelf". New York Times. March 15, 1998. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- About James Claussen, Website of James Claussen. Retrieved January 6, 2020

- Cotter, Holland (June 10, 2000). "Jacob Lawrence Is Dead at 82; Vivid Painter Who Chronicled Odyssey of Black Americans". New York Times. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- "The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation website". Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- "The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation Website's Searchable Archive". Archived from the original on July 7, 2008.

- Russell, Dick (2009). Black Genius: Inspirational Portraits of America's Black Leaders. Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. p. 100. ISBN 1626366462.

- "New York in Transit, Jacob Lawrence (2001)" Archived March 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, NYC Subway Organization

- Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (February 27, 2005). "Gwendolyn Knight, 91, Artist Who Blossomed Late in Life, Is Dead". New York Times. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- "Jacob Lawrence | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on May 14, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter L" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- "RECIPIENTS OF THE ALGUR H. MEADOWS AWARD FOR EXCELLENCE IN THE ARTS". SMU News. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007.

- "Tour: African American Artists: Collection Highlights". National Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- Trescott, Jacqueline (September 20, 2007). "Green Room Makeover Incorporates a Colorful Past". Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 5, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2007.

- Most frequently requested artists Archived February 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Artists Rights Society

- exhibit-E.com. "Jacob Lawrence - Artists - DC Moore Gallery". dcmooregallery.com. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- Seattle Art Museum, About the Gwendolyn Knight & Jacob Lawrence Fellowship Archived June 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, 2009.

- Bryan, Mason. "Jacob Lawrence and the art of radical imagination". crosscut.com. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

Further reading

- Bearden, Romare and Henderson, Harry. A History of African-American Artists (From 1792 to the Present), pp. 293–314, Pantheon Books (Random House), 1993, ISBN 0-394-57016-2

- Miles, J. H., Davis, J. J., Ferguson-Roberts, S. E., and Giles, R. G. (2001). Almanac of African American Heritage, Paramus, NJ: Prentice Hall Press.

- Potter, J. (2002). African American Firsts, New York, NY: Kensington Publishing Corp.

- Nesbett, Peter T., and DuBose, Michelle (2000), Jacob Lawrence: paintings, drawings, and murals (1935–1999): a catalogue raisonné

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jacob Lawrence. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Jacob Lawrence |

- "Jacob Lawrence", Queens Museum of Art website; includes reproductions of several prints from the John Brown series.

- The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation website, works at Phillips Collection

- Interactive website about Jacob Lawrence's life and work.

- Jacob Lawrence, Interior Scene (click on picture for larger image), Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio

- Jacob Lawrence Information and Artwork at Woodside Braseth Gallery, Seattle

- Jacob Lawrence at Find a Grave