Shirley Temple

Shirley Temple Black[note 1] (April 23, 1928 – February 10, 2014) was an American actress, singer, dancer, businesswoman, and diplomat who was Hollywood's number one box-office draw as a child actress from 1935 to 1938. As an adult, she was named United States ambassador to Ghana and to Czechoslovakia, and also served as Chief of Protocol of the United States.

Shirley Temple | |

|---|---|

Temple in 1948 | |

| Born | April 23, 1928 Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Died | February 10, 2014 (aged 85) Woodside, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Alta Mesa Memorial Park, Palo Alto, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | United States |

| Other names | Shirley Temple Black |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1932–65 (as actress) 1967–92 (as public servant) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 3, including Lori Black |

| 27th United States Ambassador to Czechoslovakia | |

| In office August 23, 1989 – July 12, 1992 | |

| President | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Julian Niemczyk |

| Succeeded by | Adrian A. Basora |

| 18th Chief of Protocol of the United States | |

| In office July 1, 1976 – January 21, 1977 | |

| President | Gerald Ford Jimmy Carter |

| Preceded by | Henry E. Catto Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Evan Dobelle |

| 9th United States Ambassador to Ghana | |

| In office December 6, 1974 – July 13, 1976 | |

| President | Gerald Ford |

| Preceded by | Fred L. Hadsel |

| Succeeded by | Robert P. Smith |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Republican |

| Website | shirleytemple |

| Signature | |

Temple began her film career at the age of three in 1931. Two years later, she achieved international fame in Bright Eyes, a feature film designed specifically for her talents. She received a special Juvenile Academy Award in February 1935 for her outstanding contribution as a juvenile performer in motion pictures during 1934. Film hits such as Curly Top and Heidi followed year after year during the mid-to-late 1930s. Temple capitalized on licensed merchandise that featured her wholesome image; the merchandise included dolls, dishes, and clothing. Her box-office popularity waned as she reached adolescence.[1] She appeared in 29 films from the ages of 3 to 10 but in only 14 films from the ages of 14 to 21. Temple retired from film in 1950 at the age of 22.[2][3]

In 1958, Temple returned to show business with a two-season television anthology series of fairy tale adaptations. She made guest appearances on television shows in the early 1960s and filmed a sitcom pilot that was never released. She sat on the boards of corporations and organizations including The Walt Disney Company, Del Monte Foods, and the National Wildlife Federation.

She began her diplomatic career in 1969, when she was appointed to represent the United States at a session of the United Nations General Assembly, where she worked at the U.S. Mission under Ambassador Charles W. Yost. In 1988, she published her autobiography, Child Star.[4]

Temple was the recipient of numerous awards and honors, including the Kennedy Center Honors and a Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award. She is 18th on the American Film Institute's list of the greatest female American screen legends of Classic Hollywood cinema.

Early years

Shirley Temple was born on April 23, 1928, at UCLA Medical Center, Santa Monica in Santa Monica, California,[5] the third child of homemaker Gertrude Temple and bank employee George Temple. The family was of Dutch, English, and German ancestry.[6][7] She had two brothers: John and George, Jr.[7][8][9] The family moved to Brentwood, Los Angeles.[10]

Her mother encouraged Shirley to develop her singing, dancing, and acting talents, and in September 1931 enrolled her in Meglin's Dance School in Los Angeles.[11][12][13] At about this time, Shirley's mother began styling her daughter's hair in ringlets.[14]

While at the dance school, she was spotted by Charles Lamont, who was a casting director for Educational Pictures. Temple hid behind the piano while she was in the studio. Lamont took a liking to Temple, and invited her to audition; he signed her to a contract in 1932. Educational Pictures launched its Baby Burlesks,[15][16][17][18] 10-minute comedy shorts satirizing recent films and events, using preschool children in every role. Glad Rags to Riches was a parody of the Mae West feature She Done Him Wrong, with Shirley as a saloon singer. Kid 'n' Africa had Shirley imperiled in the jungle. The Runt Page was a pastiche of The Front Page. The juvenile cast delivered their lines as best they could, with the younger players reciting phonetically. Temple became the breakout star of this series, and Educational promoted her to 20-minute comedies. These were in the Frolics of Youth series with Frank Coghlan Jr.; Temple played Mary Lou Rogers, the baby sister in a contemporary suburban family.[19] To underwrite production costs at Educational Pictures, she and her child co-stars modeled for breakfast cereals and other products.[20][21] She was lent to Tower Productions for a small role in her first feature film (The Red-Haired Alibi) in 1932[22][23] and, in 1933, to Universal, Paramount, and Warner Bros. Pictures for various parts.[24][25]

Film career

Fox Film songwriter Jay Gorney was walking out of the viewing of Temple's last Frolics of Youth picture when he saw her dancing in the movie theater lobby. Recognizing her from the screen, he arranged for her to have a screen test for the movie Stand Up and Cheer! Temple arrived for the audition on December 7, 1933; she won the part and was signed to a $150-per-week contract that was guaranteed for two weeks by Fox Film Corporation. The role was a breakthrough performance for Temple. Her charm was evident to Fox executives, and she was ushered into corporate offices almost immediately after finishing "Baby, Take a Bow", a song-and-dance number she performed with James Dunn.

Roles

Most of the Shirley Temple films were inexpensively made at $200,000 or $300,000 apiece, and were comedy-dramas with songs and dances added, sentimental and melodramatic situations, and bearing little production value. Her film titles are a clue to the way she was marketed—Curly Top and Dimples, and her "little" pictures such as The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel. Shirley often played a fixer-upper, a precocious Cupid, or the good fairy in these films, reuniting her estranged parents or smoothing out the wrinkles in the romances of young couples.[26] Elements of the traditional fairy tale were woven into her films: wholesome goodness triumphing over meanness and evil, for example, or wealth over poverty, marriage over divorce, or a booming economy over a depressed one.[27] As the girl matured into a pre-adolescent, the formula was altered slightly to encourage her naturalness, naïveté, and tomboyishness to come forth and shine while her infant innocence, which had served her well at six but was inappropriate for her tweens (or later childhood years), was toned down.[26]

Biographer John Kasson argues:

- In almost all of these films she played the role of emotional healer, mending rifts between erstwhile sweethearts, estranged family members, traditional and modern ways, and warring armies. Characteristically lacking one or both parents, she constituted new families of those most worthy to love and protect her. Producers delighted in contrasting her diminutive stature, sparkling eyes, dimpled smile, and fifty-six blond curls by casting her opposite strapping leading men, such as Gary Cooper, John Boles, Victor McLaglen, and Randolph Scott. Yet her favorite costar was the great African American tap dancer Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, with whom she appeared in four films, beginning with The Little Colonel (1935), in which they performed the famous staircase dance.[28]

Biographer Anne Edwards wrote about the tone and tenor of Shirley Temple films:

- This was mid-Depression, and schemes proliferated for the care of the needy and the regeneration of the fallen. But they all required endless paperwork and demeaning, hours-long queues, at the end of which an exhausted, nettled social worker dealt with each person as a faceless number. Shirley offered a natural solution: to open one's heart.[29]

Edwards pointed out that the characters created for Temple would change the lives of the cold, the hardened, and the criminal with positive results. Her films were seen as generating hope and optimism, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt said, "It is a splendid thing that for just fifteen cents, an American can go to a movie and look at the smiling face of a baby and forget his troubles."[30][note 2]

Finances

On December 21, 1933, her contract was extended to a year at the same $150 per week with a seven-year option, and her mother Gertrude was hired at $25 per week as her hairdresser and personal coach.[31] Released in May 1934, Stand Up and Cheer! became Shirley's breakthrough film.[32] She performed in a short skit in the film alongside popular Fox star James Dunn, singing and tap dancing. The skit was the highlight of the film, and Fox executives rushed her into another film with Dunn, Baby Take a Bow (named after their song in Stand Up and Cheer!). Shirley's third film, also with Dunn, was Bright Eyes, a vehicle written especially for her.[33]

After the success of her first three films, Shirley's parents realized that their daughter was not being paid enough money. Her image also began to appear on numerous commercial products without her legal authorization and without compensation. To get control over the corporate unlicensed use of her image and to negotiate with Fox, Temple's parents hired lawyer Lloyd Wright to represent them. On July 18, 1934, the contractual salary was raised to $1,000 per week; meanwhile, her mother's salary was raised to $250 per week, with an additional $15,000 bonus for each movie finished. Temple's original contract for $150 per week is equivalent to $2,960 in 2019, adjusted for inflation; however, the economic value of $150 during the Great Depression was equal to around $18,500 in 2019 money due to the punishing effects of deflation—six times higher than a surface-level conversion. The subsequent salary increase to $1,000 weekly had the economic value of $123,000 in 2019 money, and the bonus of $15,000 per movie (equal to $296,000 in 2019) had the purchasing power of $1.85 million (in 2019 money) in a decade when a quarter could buy a meal.[34] Cease and desist letters were sent out to many companies and the process was begun for awarding corporate licenses.[35]

.jpg)

On December 28, 1934, Bright Eyes was released. The movie was the first feature film crafted specifically for Temple's talents and the first where her name appeared over the title.[36][37] Her signature song, "On the Good Ship Lollipop", was introduced in the film and sold 500,000 sheet-music copies. In February 1935, Temple became the first child star to be honored with a miniature Juvenile Oscar for her film accomplishments,[38][39][40][note 3] and she added her footprints and handprints to the forecourt at Grauman's Chinese Theatre a month later.[41]

Superstar

In 1935, Fox Films merged with Twentieth Century Pictures to become 20th Century Fox. Producer and studio head Darryl F. Zanuck focused his attention and resources upon cultivating Shirley's superstar status. She was said to be the studio's greatest asset. Nineteen writers, known as the Shirley Temple Story Development team, made 11 original stories and some adaptations of the classics for her.[42]

In keeping with her star status, Winfield Sheehan built Temple a four-room bungalow at the studio with a garden, a picket fence, a tree with a swing, and a rabbit pen. The living room wall was painted with a mural depicting her as a fairy-tale princess wearing a golden star on her head. Under Zanuck, she was assigned a bodyguard, John Griffith, a childhood friend of Zanuck's,[43] and, at the end of 1935, Frances "Klammie" Klampt became her tutor at the studio.[44]

1935–1937

In the contract they signed in July 1934, Temple's parents agreed to four films a year (rather than the three they wished). A succession of films followed: The Little Colonel, Our Little Girl, Curly Top (with the signature song "Animal Crackers in My Soup"), and The Littlest Rebel in 1935. Curly Top and The Littlest Rebel were named to Variety's list of top box office draws for 1935.[45]

In 1936, Captain January, Poor Little Rich Girl, Dimples,[note 4] and Stowaway were released. Curly Top was Shirley's last film before the merger between 20th Century Pictures, Inc. and the Fox Film Corporation.

Based on Temple's success, Zanuck increased budgets and production values for her films. By the end of 1935, her salary was $2,500 a week.[46] In 1937, John Ford was hired to direct the sepia-toned Wee Willie Winkie (Temple's own favorite), and an A-list cast was signed that included Victor McLaglen, C. Aubrey Smith and Cesar Romero.[47][48] Elaborate sets were built at the famed Iverson Movie Ranch in Chatsworth, for the production, with a rock feature at the heavily filmed location ranch eventually being named the Shirley Temple Rock. The film was a critical and commercial hit.[49]

Temple's parents and Twentieth Century-Fox sued British writer/critic Graham Greene for libel and won. The settlement remained in trust for the girl in an English bank until she turned 21, when it was donated to charity and used to build a youth center in England. [50][51]

Heidi was the only other Temple film released in 1937.[50] Midway through shooting of the movie, the dream sequence was added to the script. There were reports that Temple herself was behind the dream sequence and she had enthusiastically pushed for it, but in her autobiography she vehemently denied this. Her contract gave neither her or her parents any creative control over her movies. She saw this as the refusal of any serious attempt by Zanuck to build upon the success of her dramatic role in Wee Willie Winkie.[52]

One of the many examples of how Temple was permeating popular culture at the time is the references to her in the 1937 film Stand-In: newly-minted film studio honcho Atterbury Dodd (played by Leslie Howard) has never heard of Temple, much to the shock and disbelief of former child star Lester Plum (played by Joan Blondell), who describes herself as "the Shirley Temple of my day", and performs "On the Good Ship Lollipop" for him.

1938–1940

The Independent Theatre Owners Association paid for an advertisement in The Hollywood Reporter in May 1938 that included Temple on a list of actors who deserved their salaries while others' (including Katharine Hepburn and Joan Crawford) "box-office draw is nil".[53]

That year, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, Little Miss Broadway and Just Around the Corner were released. The latter two were panned by the critics, and Corner was the first of her films to show a slump in ticket sales.[54] The following year, Zanuck secured the rights to the children's novel A Little Princess, believing the book would be an ideal vehicle for the girl. He budgeted the film at $1.5 million (twice the amount of Corner) and chose it to be her first Technicolor feature. The Little Princess was a 1939 critical and commercial success, with Shirley's acting at its peak.

Convinced that the girl would successfully move from child star to teenage actress, Zanuck declined a substantial offer from MGM to star her as Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, and cast her instead in Susannah of the Mounties, her last money-maker for Twentieth Century Fox.[55][56] The film was successful, but because she made only two films in 1939, instead of three or four, Shirley dropped from number one box-office favorite in 1938 to number five in 1939.[57]

In 1939, she was the subject of the Salvador Dalí painting Shirley Temple, The Youngest, Most Sacred Monster of the Cinema in Her Time, and she was animated with Donald Duck in The Autograph Hound.

In 1940, Lester Cowan, an independent film producer, bought the screen rights to F. Scott Fitzgerald's "Babylon Revisited and Other Stories" for $80, which was a bargain. Fitzgerald thought his screenwriting days were over, and, with some hesitation, accepted Cowan's offer to write the screenplay titled "Cosmopolitan" based on the short story. After finishing the screenplay, Fitzgerald was told by Cowan that he would not do the film unless Temple starred in the lead role of the youngster Honoria. Fitzgerald objected, saying that at age 12 (going on twenty), the actress was too worldly for the part and would detract from the aura of innocence otherwise framed by Honoria's character. After meeting Shirley in July, Fitzgerald changed his mind, and tried to persuade her mother to let her star in the film. However, her mother demurred. In any case, the Cowan project was shelved by the producer. Fitzgerald was later credited with the use of the original story for The Last Time I Saw Paris starring Elizabeth Taylor.[58]

In 1940, Shirley starred in two flops at Twentieth Century Fox—The Blue Bird and Young People.[59][60] Her parents bought out the remainder of her contract, and sent her—at the age of 12—to Westlake School for Girls, an exclusive country day school in Los Angeles.[61] At the studio, the girl's bungalow was renovated, all traces of her tenure expunged, and the building was reassigned as an office.[60]

1941–1950 retirement

After her departure from Twentieth Century-Fox,[note 5] Shirley was signed by MGM for her comeback; the studio made plans to team her with Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney for the Andy Hardy series. However, upon meeting with Arthur Freed for a preliminary interview, the MGM producer exposed his genitals to her. When this elicited nervous giggles in response, Freed threw her out and ended their contract before any films were produced.[62] The next idea was teaming her with Garland and Rooney for the musical Babes on Broadway. Fearing that either of the latter two could easily upstage Temple, MGM replaced her with Virginia Weidler. As a result, her only film for Metro was Kathleen in 1941, a story about an unhappy teenager. The film was not a success, and her MGM contract was canceled after mutual consent. Miss Annie Rooney followed for United Artists in 1942, but was unsuccessful.[note 6] The actress retired from films for almost two years, to instead focus on school and activities.[63]

In 1944, David O. Selznick signed Temple to a four-year contract. She appeared in two wartime hits: Since You Went Away, and I'll Be Seeing You. Selznick, however, became romantically involved with Jennifer Jones and lost interest in developing Shirley's career. Temple was then lent to other studios. Kiss and Tell, The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer,[note 7] and Fort Apache were her few hit films at the time.[64]

According to biographer Robert Windeler, her 1947–1949 films neither made nor lost money, but "had a cheapie B look about them and indifferent performances from her".[65] Selznick suggested that she move abroad, gain maturity as an actress, and even change her name. He warned her that she was typecast, and her career was in perilous straits.[65][66] After unsuccessfully auditioning for the role of Peter Pan on the Broadway stage in August 1950,[67] Temple took stock, and admitted that her recent movies had been poor fare. She announced her retirement from films on December 16, 1950.[65][68]

Radio career

Temple had her own radio series on CBS. Junior Miss debuted March 4, 1942, in which she played the title role. The series was based on stories by Sally Benson. Sponsored by Procter & Gamble, Junior Miss was directed by Gordon Hughes, with David Rose as musical director.[69]

Merchandise and endorsements

John Kasson states:

- She was also the most popular celebrity to endorse merchandise for children and adults, rivaled only by Mickey Mouse. She transformed children's fashions, popularizing a toddler look for girls up to the age of twelve, and by the mid-1930s Ideal Novelty and Toy Company's line of Shirley Temple dolls accounted for almost a third of all dolls sold in the country.[28]

Ideal Toy and Novelty Company in New York City negotiated a license for dolls with the company's first doll wearing the polka-dot dress from Stand Up and Cheer! Shirley Temple dolls realized $45 million in sales before 1941.[70] A mug, a pitcher, and a cereal bowl in cobalt blue with a decal of the little actress were given away as a premium with Wheaties.

Successful Shirley Temple items included a line of girls' dresses, accessories, soap, dishes, cutout books, sheet music, mirrors, paper tablets, and numerous other items. Before 1935 ended, the girl's income from licensed merchandise royalties would exceed $100,000, which doubled her income from her movies. In 1936, her income from royalties topped $200,000. She endorsed Postal Telegraph, Sperry Drifted Snow Flour, the Grunow Teledial radio, Quaker Puffed Wheat,[70] General Electric, and Packard automobiles.[71][note 8]

Myths and rumors

At the height of her popularity, Temple was often the subject of many myths and rumors, with several being propagated by the Fox press department. Fox also publicized her as a natural talent with no formal acting or dance training. As a way of explaining how she knew stylized buck-and-wing dancing, she was enrolled for two weeks in the Elisa Ryan School of Dancing.[72]

False claims circulated that Temple was not a child, but a 30-year-old dwarf, due in part to her stocky body type. The rumor was so prevalent, especially in Europe, that the Vatican dispatched Father Silvio Massante to investigate whether she was indeed a child. The fact that she never seemed to miss any teeth led some people to conclude that she had all her adult teeth. Temple was actually losing her teeth regularly through her days with Fox, most notably during the sidewalk ceremony in front of Grauman's Theatre, where she took off her shoes and placed her bare feet in the cement to take attention away from her face. When acting, she wore dental plates and caps to hide the gaps in her teeth.[73] Another rumor said her teeth had been filed to make them appear like baby teeth.[74]

A rumor about Temple's trademark hair was the idea that she wore a wig. On multiple occasions, fans yanked her hair to test the rumor. She later said she wished all she had to do was wear a wig. The nightly process she endured in the setting of her curls was tedious and grueling, with weekly vinegar rinses that burned her eyes.[75]

Rumors spread that her hair color was not naturally blonde. During the making of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, news spread that she was going to do extended scenes without her trademark curls. During production, she also caught a cold, which caused her to miss a couple of days. As a result, a false report originated in Britain that all of her hair had been cut off.[74]

Television career

.jpg)

Between January 1958 and September 1961, Temple hosted and narrated a successful NBC television anthology series of fairy-tale adaptations called Shirley Temple's Storybook. Episodes ran one hour each, and Temple acted in three of the sixteen episodes. Temple's son made his acting debut in the Christmas episode, "Mother Goose".[76][77] The series was popular but faced issues. The show lacked the special effects necessary for fairy tale dramatizations, sets were amateurish, and episodes were not telecast in a regular time-slot.[78] The show was reworked and released in color in September 1960 in a regular time-slot as The Shirley Temple Show.[79][80] It faced stiff competition from Maverick, Lassie, Dennis the Menace, the 1960 telecast of The Wizard of Oz, and the Walt Disney anthology television series however, and was canceled at season's end in September 1961.[81]

Temple continued to work in television, making guest appearances on The Red Skelton Show, Sing Along with Mitch, and other shows.[79] In January 1965, she portrayed a social worker in a pilot called Go Fight City Hall that was never released.[82]

In 1999, she hosted the AFI's 100 Years...100 Stars awards show on CBS, and in 2001 served as a consultant on an ABC-TV production of her autobiography, Child Star: The Shirley Temple Story.[83]

Motivated by the popularity of Storybook and television broadcasts of Temple's films, the Ideal Toy Company released a new version of the Shirley Temple doll, and Random House published three fairy-tale anthologies under her name. Three-hundred-thousand dolls were sold within six months, and 225,000 books between October and December 1958. Other merchandise included handbags and hats, coloring books, a toy theater, and a recreation of the Baby, Take a Bow polka-dot dress.[84]

Diplomatic career

Temple became active in the California Republican Party. In 1967, she ran unsuccessfully in a special election in California's 11th congressional district to fill the seat left vacant by the leukemia death of eight-term Republican J. Arthur Younger.[85][86] She ran in the open primary as a conservative Republican and came in second with 34,521 votes (22.44%), behind Republican law school professor Pete McCloskey, who placed first in the primary with 52,882 votes (34.37%) and advanced to the general election with Democrat Roy A. Archibald, who finished fourth with 15,069 votes (9.79%), but advanced as the highest-placed Democratic candidate. In the general election, McCloskey was elected with 63,850 votes (57.2%) to Archibald's 43,759 votes (39.2%). Temple received 3,938 votes (3.53%) as an independent write-in.[87][88]

Temple was extensively involved with the Commonwealth Club of California, a public-affairs forum headquartered in San Francisco. She spoke at many meetings through the years, and was president for a period in 1984.[89][90]

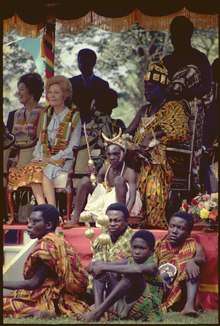

Temple got her start in foreign service after her failed run for Congress in 1967 when Henry Kissinger overheard her talking about South West Africa at a party. He was surprised that she knew anything about it.[91] She was appointed as a delegate to the 24th United Nations General Assembly (September – December 1969) by President Richard M. Nixon[92][93][94] and United States Ambassador to Ghana (December 6, 1974 – July 13, 1976) by President Gerald R. Ford.[95] She was appointed first female Chief of Protocol of the United States (July 1, 1976 – January 21, 1977), and in charge of arrangements for President Jimmy Carter's inauguration and inaugural ball.[95][96]

She served as the United States Ambassador to Czechoslovakia (August 23, 1989 – July 12, 1992), having been appointed by President George H. W. Bush,[71] and was the first and only female in this job. Temple bore witness to two crucial moments in the history of Czechoslovakia's fight against communism. She was in Prague in August 1968, as a representative of the International Federation of Multiple Sclerosis Societies, and going to meet with Czechoslovakian party leader Alexander Dubček on the very day that Soviet-backed forces invaded the country. Dubček fell out of favor with the Soviets after a series of reforms known as the Prague Spring. Temple, who was stranded at a hotel as the tanks rolled in, sought refuge on the roof of the hotel. She later reported that it was from here she saw an unarmed woman on the street gunned down by Soviet forces, the sight of which stayed with her for the rest of her life.[97]

Later, after she became ambassador to Czechoslovakia, she was present in the Velvet Revolution, which brought about the end of communism in Czechoslovakia. Temple openly sympathized with anti-communist dissidents and was ambassador when the US established formal diplomatic relations with the newly elected government led by Václav Havel. She took the unusual step of personally accompanying Havel on his first official visit to Washington, travelling on the same plane.[91]

Temple served on boards of directors of large enterprises and organizations such as The Walt Disney Company, Del Monte Foods, Bank of America, Bank of California, BANCAL Tri-State, Fireman's Fund Insurance, United States Commission for UNESCO, United Nations Association and National Wildlife Federation.[98]

Personal life

In 1943, 15-year-old Temple met John Agar (1921–2002), an Army Air Corps sergeant, physical training instructor, and member of a Chicago meat-packing family.[99][100] She married him at age 17 on September 19, 1945, before 500 guests in an Episcopal ceremony at Wilshire Methodist Church in Los Angeles.[101][102][103] On January 30, 1948, Temple bore a daughter, Linda Susan.[101][104][105] Agar became an actor, and the couple made two films together: Fort Apache (1948, RKO) and Adventure in Baltimore (1949, RKO). The marriage became troubled, and Temple divorced Agar on December 5, 1949. She was awarded custody of their daughter.[105]

In January 1950, Temple met Charles Alden Black, a World War II Navy intelligence officer and Silver Star recipient who was Assistant to the President of the Hawaiian Pineapple Company.[106][107] Conservative and patrician, he was the son of James Black, president and later chairman of Pacific Gas and Electric, and reputedly one of the richest young men in California. Temple and Black were married in his parents' Del Monte, California home on December 16, 1950, before a small assembly of family and friends.[101][107][108]

The family moved to Washington, D.C., when Black was recalled to the Navy at the outbreak of the Korean War.[109] On April 28, 1952, Temple gave birth to a son, Charles Alden Black Jr., in Washington.[101][110][111] Following the war's end and Black's discharge from the Navy, the family returned to California in May 1953. Black managed television station KABC-TV in Los Angeles, and Temple became a homemaker. Their daughter, Lori, was born on April 9, 1954;[101] she went on to be a bassist for the rock band the Melvins.

In September 1954, Charles Sr. became director of business operations for the Stanford Research Institute, and the family moved to Atherton, California.[112] The couple were married for 54 years until his death on August 4, 2005, at his home in Woodside, California, of complications from a bone marrow disease.[113]

Breast cancer

At age 44, in 1972, Temple was diagnosed with breast cancer. The tumor was removed and a modified radical mastectomy performed. At the time, cancer was typically discussed in hushed whispers, and Temple's public disclosure was a significant milestone in improving breast cancer awareness and reducing stigma around the disease.[114] She announced the results of the operation on radio and television and in a February 1973 article for the magazine McCall's.

Death

Temple died at age 85 on February 10, 2014, at her home in Woodside, California.[115][116] The cause of death, according to her death certificate released on March 3, 2014, was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).[117] Temple was a lifelong cigarette smoker but avoided displaying her habit in public because she did not want to set a bad example for her fans.[118]

Awards, honors, and legacy

Temple was the recipient of many awards and honors, including a special Juvenile Academy Award,[101] the Life Achievement Award from the American Center of Films for Children,[95] the National Board of Review Career Achievement Award,[119] Kennedy Center Honors,[120][121] and the Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award.[122]

On March 14, 1935, Shirley left her footprints and handprints in the wet cement at the forecourt of Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood. She was the Grand Marshal of the New Year's Day Rose Parade in Pasadena, California, three times in 1939, 1989, and 1999. On February 8, 1960, she received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

In February 1980, Temple was honored by the Freedoms Foundation of Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, along with U.S. Senator Jake Garn, actor James Stewart, singer John Denver, and Tom Abraham, an American businessman who worked with immigrants seeking to become US citizens.[123]

On September 11, 2002, a life-size bronze statue of the child Temple by sculptor Nijel Binns was erected on the Fox Studio lot.[124]

Her name is further immortalized by the mocktail named after her, although Temple found the drink far too sweet for her palate.

Filmography

See also

- List of former child actors from the United States

- List of oldest and youngest Academy Award winners and nominees

Notes

- While Temple occasionally used "Jane" as a middle name, her birth certificate reads "Shirley Temple". Her birth certificate was altered to prolong her babyhood shortly after she signed with Fox in 1934; her birth year was advanced from 1928 to 1929. Even her baby book was revised to support the 1929 date. She confirmed her true age when she was 21 (Burdick 5; Edwards 23n, 43n).

- Shirley and her parents traveled to Washington, D.C. late in 1935 to meet Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor. The presidential couple invited the Temple family to a cook-out at their home, where Eleanor, bending over an outdoor grill, was hit smartly in the rear with a pebble from the slingshot that Shirley carried everywhere in her little lace purse (Edwards 81).

- Temple was presented with a full-sized Oscar in 1985 (Edwards 357).

- In Dimples, Temple was upstaged for the first time in her film career by Frank Morgan, who played Professor Appleby with such zest as to render the child actress almost the amateur (Windeler 175).

- In 1941, Temple worked radio with four shows for Lux soap and a four-part Shirley Temple Time for Elgin. Of radio, she said, "It's adorable. I get a big thrill out of it, and I want to do as much radio work as I can." (Windeler 43)

- the teenager received her first on-screen kiss in the film (from Dickie Moore, on the cheek) (Edwards 136).

- When she took her first on-screen drink (and spat it out) in Bobby-Soxer, the Women's Christian Temperance Union protested that unthinking teenagers might do the same after seeing the teenage Shirley in the films (Life Staff 140).

- In the 1990s, audio recordings of the girl's film songs and videos of her films were released, but she received no royalties. Porcelain dolls were created by Elke Hutchens. The Danbury Mint released plates and figurines depicting her in her film roles, and, in 2000, a porcelain tea set (Burdick 136)

References

- "Shirley Temple". biography.com. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- Balio 227

- Windeler 26

- Child Star. McGraw-Hill. 1998. ISBN 978-0-07-005532-2.

- "Love, Shirley Temple, Collector's Book: 4 Shirley Temple's Official Hospital Birth Certificate". www.theriaults.com. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- Edwards 15, 17

- Windeler 16

- Edwards 15

- Burdick 3

- A look at the late Shirley Temple's very first home, Yahoo!. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- Edwards 29–30

- Windeler 17

- Burdick 6

- Edwards 26

- Edwards 31

- Black 14

- Edwards 31–34

- Windeler 111

- Windeler 113, 115, 122

- Black 15

- Edwards 36

- Black 28

- Edwards 37, 366

- Edwards 267–269

- Windeler 122

- Balio 227–228

- Zipes 518

- Kasson, American National Biography (2015)

- Edwards 75

- Edwards 75–76

- Shirley Temple Black, Child Star: An Autobiography, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1988, 32–36.

- Barrios 421

- Kasson 80–83

- "Measuring Worth – Results". measuringworth.com. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- Shirley Temple Black, Child Star: An Autobiography, New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1988, pp. 79–83.

- Edwards 67

- Windeler 143

- Black 98–101

- Edwards 80

- Windeler 27–28

- Black 72

- Edwards 74–75

- Edwards 77

- Edwards 78

- Balio 228

- Shirley Temple Black, Child Star: An Autobiography, New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1988, 130.

- Windeler 183

- Edwards 104–105

- Edwards 105, 363

- Edwards 106

- Windeler 35

- Shirley Temple Black, Child Star: An Autobiography, New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1988, 192–193

- "Box-office Busts/Boys and Girls". Life. pp. 13, 28. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- Edwards 120–121

- Edwards 122–123

- Windeler 207

- Edwards 124

- E. Ray Canterbery and Thomas D. Birch, F. Scott Fitzgerald: Under the Influence, St. Paul, Minn.: Paragon House, 2006, pp. 347–352.

- Burdick 268

- Edwards 128

- Windeler 38

- Harmetz, Aljean (February 11, 2014). "Shirley Temple Black, Hollywood's Biggest Little Star, Dies at 85". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- Windeler 43–45

- Windeler 49–52

- Windeler 71

- Edwards 206

- Edwards 209

- Black 479–481

- "Shirley Temple in Title Role Of 'Junior Miss' Radio Drama". Harrisburg Telegraph. February 28, 1942. p. 22. Retrieved March 28, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- Black 85–86

- Thomas; Scheftel

- Black, Shirley Temple (1988). Child Star: An Autobiography. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 39–41. ISBN 978-0-07-005532-2.

- Black, Shirley Temple (1988). Child Star: An Autobiography. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 72–73, . ISBN 978-0-07-005532-2.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Lindeman, Edith. "The Real Miss Temple". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Archived from the original on March 7, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- Black, Shirley Temple (1988). Child Star: An Autobiography. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-07-005532-2.

- Edwards 231, 233, 393

- Windeler 255

- Burdick 112–113

- Edwards 393

- Burdick 115

- Burdick 115–116

- Edwards 235–236, 393

- "Child Star: The Shirley Temple Story (2001)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- Edwards 233

- Edwards 243ff

- Windeler 80ff

- Sean Howell (July 1, 2009). "Documentary salutes Pete McCloskey". The Almanac Online. Embarcadero Publishing Co. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- Romney, Lee (June 11, 2012). "Between two public servants, Purple Heart-felt admiration". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2012. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "In Memoriam: Shirley Temple Black". commonwealthclub.org. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- Joshua Keating, "Shirley Temple Black's Unlikely Diplomatic Career: Including an Encounter with Frank Zappa", Slate, February 11, 2014.

- Edwards 356

- Windeler 85

- Aljean Harmetz, "Shirley Temple Black, Hollywood's Biggest Little Star, Dies at 85", The New York Times, February 11, 2014

- Edwards 357

- Windeler 105

- Craig R. Whitney, "Prague Journal: Shirley Temple Black Unpacks a Bag of Memories", The New York Times, September 11, 1989.

- Edwards 318, 356–357

- Edwards 147

- Windeler 53

- Edwards 355

- Edwards 169

- Windeler 54

- Black 419–421

- Windeler 68

- Edwards 207

- Windeler 72

- Edwards 211

- Edwards 215

- Edwards 217

- Windeler 72–73

- Windeler 74

- Dawicki 2005

- Olson, James Stuart (2002). Bathsheba's Breast: Women, Cancer and History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 124–144. ISBN 978-0-8018-6936-5. OCLC 186453370.

- "Hollywood star Shirley Temple dies". BBC News. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- "Shirley Temple, former Hollywood child star, dies at 85". Reuters. February 11, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- Dicker, Chris. Shirley Temple Biography: The 'Perfect Life' of the Child Star Shirley Temple During the Great Depression. Chris Dicker.

- "Obituary: Shirley Temple". BBC News. February 11, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- "Shirley Temple Black". The National Board of Review. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- "History of Past Honorees". The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Archived from the original on January 14, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- Burdick 136

- "Shirley Temple Black: 2005 Life Achievement Recipient". Screen Actors Guild. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- "Tom Abraham to be honored by Freedoms Foundation Feb. 22", Canadian Record, February 14, 1980, p. 19

- "The Shirley Temple Monument". Nijart. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

Bibliography

- Balio, Tino (1995) [1993]. Grand Design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, 1930–1939. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20334-1.

- Barrios, Richard (1995). A Song in the Dark: The Birth of the Musical Film. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-508810-6.

- Black, Shirley Temple (1989) [1988]. Child Star: An Autobiography. Warner Books, Inc. ISBN 978-0-446-35792-0., primary source

- Burdick, Loraine (2003). The Shirley Temple Scrapbook. Jonathan David Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8246-0449-3.

- Dawicki, Shelley (August 10, 2005). "In Memoriam: Charles A. Black". Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- Edwards, Anne (1988). Shirley Temple: American Princess. William Morrow and Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-688-06051-0.

- Kasson, John F. (2015) "Black, Shirley Temple" American National Biography (2015) online

- Hatch, Kristen. (2015) Shirley Temple and the Performance of Girlhood (Rutgers University Press, 2015) x, 173 pp.

- "Tempest Over Temple: Shirley sips liquor and the W.C.T.U. protests". Life. 21 (12): 140. September 16, 1946.

- Thomas, Andy; Scheftel, Jeff (1996). Shirley Temple: The Biggest Little Star. Biography. A&E Television Networks. ISBN 978-0-7670-8495-6.

- Windeler, Robert (1992) [1978]. The Films of Shirley Temple. Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8065-0725-5.

- Zipes, Jack, ed. (2000). The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-9653635-7-0.

Further reading

- Basinger, Jeanine (1993). A Woman's View: How Hollywood Spoke to Women, 1930–1960. Wesleyan University Press. pp. 262ff. ISBN 978-0-394-56351-0.

- Best, Marc (1971). Those Endearing Young Charms: Child Performers of the Screen. South Brunswick and New York: Barnes & Co. pp. 251–255.

- Bogle, Donald (2001) [1974]. Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films. The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. pp. 45–52. ISBN 978-0-8264-1267-6.

- Cook, James W.; Glickman, Lawrence B.; O'Malley, Michael (2008). The Cultural Turn in U.S. History: Past, Present, and Future. University of Chicago Press. pp. 186ff. ISBN 978-0-226-11506-1.

- Dye, David (1988). Child and Youth Actors: Filmography of Their Entire Careers, 1914–1985. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., pp. 227–228.

- Everett, Charles (2004) [1974]. "Shirley Temple and the House of Rockefeller". Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media (2): 1, 17–20.

- Kasson, John F. The Little Girl Who Fought the Great Depression: Shirley Temple and 1930s America (2014) Excerpt

- Minott, Rodney G. The Sinking of the Lollipop: Shirley Temple vs. Pete McCloskey (1968).

- Thomson, Rosemarie Garland, ed. (1996). Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body. New York University Press. pp. 185–203. ISBN 978-0-8147-8217-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shirley Temple. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Shirley Temple |

- Official website

- Shirley Temple on IMDb

- Shirley Temple at the TCM Movie Database

- Shirley Temple at Find a Grave

- Photographs of Shirley Temple

- Wee Willie Winkie at the Iverson Movie Ranch

- Norwood, Arlisha. "Shirley Temple". National Women's History Museum. 2017.

- Image of Shirley Temple and Eddie Cantor cutting President Franklin D. Roosevelt's birthday cake in Los Angeles, California, 1937. Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.