Dayak people

The Dayak /ˈdaɪ.ək/ or Dyak or Dayuh are one of the native groups of Borneo.[4] It is a loose term for over 200 riverine and hill-dwelling ethnic subgroups, located principally in the central and southern interior of Borneo, each with its own dialect, customs, laws, territory and culture, although common distinguishing traits are readily identifiable. Dayak languages are categorised as part of the Austronesian languages in Asia. The Dayak were animist in belief; however, many converted to Islam and since the 19th century there has been mass conversion to Christianity.[5] Today most Dayak still follow their ancient animistic traditions, but often state to belong to one of the six recognized religions in Indonesia.[6]

A sub-ethnic group of the Dayak people, Iban or Sea Dajak boy and girl in traditional clothing. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 6.3 million+ | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Borneo: | |

| 3,219,626[1] | |

| | 1,531,989 |

| | 1,029,182 |

| | 351,437 |

| | 80,708 |

| | 45,385 |

| | 45,233 |

| | 29,254 |

| | 20,028 |

| | 14,741 |

| | 11,329 |

| 3,138,788 | |

| | 1,835,900 |

| | 1,302,888 |

| 30,000[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Bornean languages (Sabahan language, Dayak languages), Malay (Sarawak Malay), Indonesian | |

| Religion | |

| Indonesia Roman Catholicism (32.5%), Islam (31.6%), Protestantism (30.2%), Hindu Kaharingan (4.8%)[3] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Austronesian peoples, especially Banjarese, Malay Indonesians, Rejang & Malagasy | |

History

The Dayak people of Borneo possess an indigenous account of their history, mostly in oral literature,[7] partly in writing in papan turai (wooden records),[8] and partly in common cultural customary practices.[9] Among prominent accounts of the origin of the Dayak people is the mythical oral epic of "Tetek Tahtum" by the Ngaju Dayak of Central Kalimantan; it narrates that the ancestors of the Dayak people descended from the heavens before moving from inland to the downstream shores of Borneo.

The independent state of Nansarunai, established by the Ma'anyan Dayaks prior to the 12th century, flourished in southern Kalimantan.[10] The kingdom suffered two major attacks from the Majapahit forces that caused the decline and fall of the kingdom by the year 1389; the attacks are known as Nansarunai Usak Jawa (meaning "the destruction of the Nansarunai by the Javanese") in the oral accounts of the Ma'anyan people. These attacks contributed to the migration of the Ma'anyans to the Central and South Borneo region.

The colonial accounts and reports of Dayak activity in Borneo detail carefully cultivated economic and political relationships with other communities as well as an ample body of research and study concerning the history of Dayak migrations.[11] In particular, the Iban or the Sea Dayak exploits in the South China Seas are documented, owing to their ferocity and aggressive culture of war against sea dwelling groups and emerging Western trade interests in the 18th and 19th centuries.[12]

In 1838, British adventurer James Brooke arrived to find the Sultan of Brunei fending off rebellion from inland tribes whose lands were being colonized. Sarawak was in chaos, in the view of the European colonist Brooke. Brooke put down the rebellion, and was made Governor of Sarawak in 1841, with the title of Rajah. Brooke suppressed headhunting and "piracy", namely the resistance of indigenous peoples to British naval authority around Borneo[13], and was also involved in looting, plunder, and the violent erasure of villages[14]. Brooke's most famous Iban enemy was Libau "Rentap"; Brooke led three expeditions against him and finally defeated him at Sadok Hill. Brooke had many Dayaks in his forces at this battle, and famously said "Only Dayaks can kill Dayaks. So he deployed Dayaks to kill Dayaks."[15] Sharif Mashor, a Melanau from Mukah, was another enemy of Brooke.

During World War II, Japanese forces occupied Borneo and treated all of the indigenous peoples poorly – massacres of the Malay and Dayak peoples were common, especially among the Dayaks of the Kapit Division.[16] In response, the Dayaks formed a special force to assist the Allied forces. Eleven US airmen and a few dozen Australian special operatives trained a thousand Dayaks from the Kapit Division in guerrilla warfare. This army of tribesmen killed or captured some 1,500 Japanese soldiers and provided the Allies with vital intelligence about Japanese-held oil fields.[17]

During the Malayan Emergency the British military hired Dayak headhunters to kill anti-colonial fighters of the Malayan National Liberation Army.[18] News of this reached parliament in 1952 after The Daily Worker published photographs of Royal Marines posing with Dayak trackers holding the decapitated heads of suspected communists.[19] Initially the British government denied any involvement in headhunting, until Colonial Secretary Oliver Lyttleton confirmed to parliament that the photographs were indeed authentic.[20]

Coastal populations in Borneo are largely Muslim in belief, however these groups (Tidung, Banjarese, Bulungan, Paser, Kutainese, Bakumpai) are generally considered to be Malayised and Islamised native of Borneo and heavily amalgated by the Malay people, culture and sultanate system. These groups identified themselves as Melayu or Malay subgroup due to the closer cultural identity to the Malay people,[21][22][23] compared from the Dayak umbrella classification, as the latter are traditionally associated for their pagan belief and tribal lifestyle.

The Dayak people classification are largely limited among the ethnic groups traditionally concentrated in southern and interior Sarawak and Kalimantan. Other native groups in dwelling in northern Sarawak, parts of Brunei and Sabah, chiefly the Bisayah, Orang Ulu, Kadazandusun, Melanau, Rungus and dozens of smaller group were categorised under a separate classification apart from the Dayaks due to the difference in culture and history.

Other groups in coastal areas of Sabah and northeastern Kalimantan; namely the Illanun, Tausūg, Sama and Bajau, although inhabiting and (in the case of the Tausug group) ruling the northern tip of Borneo for centuries, have their cultural origins from the southern Philippines. These groups though may be indigenous to coastal northeastern Borneo, they are nonetheless not Dayak, but instead are grouped under the separate umbrella term of Moro, especially in the Philippines.

Ethnicity

The term Dayak was coined by Europeans referring to the non-Malay and non-Muslim inhabitants of central and southern Borneo. There are seven main ethnic divisions of Dayaks according to their respective native languages which are:

- 1. Ngaju

- 2. Apo Kayan including Orang Ulu

- 3. Iban (Sea Dayak) or Hiban

- 4. Bidayuh (Land Dayak) or Klemantan

- 5. Kadazan, Dusun, Murut

- 6. Punan

- 7. Ot Danum

Under the main classifications, there are dozens of ethnics and hundreds of sub-ethnics dwelling in the Borneo island. There are over 50 ethnic Dayak groups speaking different languages. This cultural and linguistic diversity parallels the high biodiversity and related traditional knowledge of Borneo.

The above list of Dayak clusters by Tjilik Riwut was revised by the First International Dayak Congress and Exhibition in 2017 to become: Ngaju-Ot Danum, Apo Kayan-Kenyan, Iban, Klemantan, Kadazan-Dusun and Punan.

Languages

Dayaks do not speak just one language, even if just those on the island of Borneo (Kalimantan) are considered.[24] Their indigenous languages belong in the general classification of Malayo-Polynesian languages and to diverse groups such as Land Dayak, Malayic, Sabahan, and Barito languages.[25][26] Most Dayaks today are bilingual, in addition to their native language, are well-versed in Malay.

Many of Borneo's languages are endemic (which means they are spoken nowhere else). It is estimated that around 170 languages and dialects are spoken on the island and some by just a few hundred people, thus posing a serious risk to the future of those languages and related heritage.

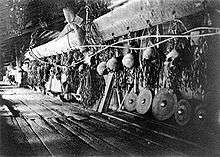

Headhunting and peacemaking

In the past, the Dayak were feared for their ancient tradition of headhunting practices (the ritual is also known as Ngayau by the Dayaks). Among the Iban Dayaks, the origin of headhunting was believed to be meeting one of the mourning rules given by a spirit which is as follows:

- The sacred jar is not to be opened except by a warrior who has managed to obtain a head, or by a man who can present a human head, which he obtained in a fight; or by a man who has returned from a sojourn in enemy country.[27]

Often, a war leader had at least three lieutenants (called manuk sabong) who in turn had some followers. The war (ngayau) rules among the Iban Dayaks are listed below:

- If a warleader leads a party on an expedition, he must not allow his warriors to fight a guiltless tribe that has no quarrel with them.

- If the enemy surrenders, he may not take their lives, lest his army be unsuccessful in future warfare and risk fighting empty-handed war raids (balang kayau).

- The first time that a warrior takes a head or captures a prisoner, he must present the head or captive to the warleader in acknowledgement of the latter's leadership.

- If a warrior takes two heads or captives, or more, one of each must be given to the warleader; the remainder belongs to the killer or captor.

- The warleader must be honest with his followers in order that in future wars he may not be defeated (alah bunoh).[28]

There were various reasons for headhunting as listed below:

- For soil fertility Dayaks hunted fresh heads before the paddy harvesting seasons after which a head festival would be held in honour of the new heads.

- To add supernatural strength which Dayaks believed to be centred in the soul and head of humans. Fresh heads can give magical powers for communal protection, bountiful paddy harvesting and disease curing.

- To exact revenge for murders based on "blood credit" principle unless "adat pati nyawa" (customary compensation token) is paid.

- To pay dowry for marriages e.g. "derian palit mata" (eye blocking dowry) for Ibans once blood has been splashed prior to agreeing to marriage and, of course, new fresh heads show prowess, bravery, ability and capability to protect his family, community and land

- For foundation of new buildings to be stronger and meaningful than the normal practice of not putting in human heads.

- For protection against enemy attacks according to the principle of "attack first before being attacked".

- As a symbol of power and social status ranking where the more heads someone has, the more respect and glory due to him. The warleader is called tuai serang (warleader) or raja berani (king of the brave) while kayau anak (small raid) leader is only called tuai kayau (raid leader) whereby adat tebalu (widower rule) after their death would be paid according to their ranking status in the community.[29]

- For territorial expansion where some brave Dayaks intentionally migrated into new areas such as Mujah "Buah Raya" or migrated from Skrang to Paku to Kanowit[30] while infighting among Ibans themselves in Batang Ai caused the Ulu Ai Ibans to migrate to Batang Kanyau River in Kapuas, Kalimantan and then proceed to Katibas and later on Ulu Rajang in Sarawak.[31] The earlier migrations from Kapuas to Batang Ai, Batang Lupar, Batang Saribas and Batang Krian rivers were also made possible by fighting the local tribes like Bukitan.

Reasons for abandoning headhunting are:

- Suppression of headhunting and piracy through punitive expeditions and enactment of relevant laws by the colonial governments such by Brooke in Sarawak and Dutch in Kalimantan.

- Peacemaking agreements at Tumbang Anoi, Kalimantan in 1874 and Kapit, Sarawak in 1924.

- Coming of Christianity, with education where Dayaks are taught that headhunting is murder and against the Christian Bible's teachings.

- Dayaks' own realisation that headhunting was more to lose than to gain

Among the most prominent legacy during the colonial rule in the Dutch Borneo (present-day Kalimantan) is the Tumbang Anoi Agreement held in 1874 in Damang Batu, Central Kalimantan (the seat of the Kahayan Dayaks). It is a formal meeting that gathered all the Dayak tribes in Kalimantan for a peace resolution. In the meeting that is reputed taken several months, the Dayak people throughout the Kalimantan agreed to end the headhunting tradition as it believed the tradition caused conflict and tension between various Dayak groups. The meeting ended with a peace resolution by the Dayak people.[32]

After mass conversions to Christianity, and anti-headhunting legislation by the colonial powers was passed, the practice was banned and appeared to have disappeared. However, the Brooke-led Sarawak government, although banning unauthorized headhunting, actually allowed "ngayau" headhunting practices by the Brooke-supporting natives during state-sanctioned punitive expeditions against their own fellow people's rebellions throughout the state, thereby never really extinguished the spirit of headhunting especially among the Iban natives. The state-sanctioned troop was allowed to take heads, properties like jars and brassware, burn houses and farms, exempted from paying door taxes and in some cases, granted new territories to migrate into. This Brooke's practice was in remarkable contrast to the practice by the Dutch in the neighbouring West Kalimantan who prohibited any native participation in its punitive expeditions. Initially, James Brooke (the first Rajah of Sarawak) did engage the British Navy troop in the Battle of Beting Maru against the Iban and Malay of the Saribas region and the Iban of Skrang under Rentap's charge but this resulted in the Public Inquiry by the British government in Singapore. Thereafter, the Brooke government gathered a local troop who were its allies.

Subsequently, the headhunting began to surface again in the mid-1940s, when the Allied Powers encouraged the practice against the Japanese Occupation of Borneo. It also slightly surged in the late 1960s when the Indonesian government encouraged Dayaks to purge Chinese from interior Kalimantan who were suspected of supporting communism in mainland China and also in the late 1990s when the Dayak started to attack Madurese emigrants in an explosion of ethnic violence.[33]

The British Empire deployed many Dayak headhunters during the Malayan Emergency against pro-independence fighters led by the Malayan Communist Party. This caused a scandal in the British parliament in 1952 when the Daily Worker published photographic evidence of British soldiers posing with said decapitated heads as trophies.

Headhunting resurfaced in 1963 among Dayak soldiers during the Confrontation Campaign by President Sukarno of Indonesia against the newly created formation of Malaysia between the pre-existing Federation of Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak on 16 September 1963. Subsequently, Dayak trackers recruited during the Malayan Emergency against the Communists' Insurgency wanted to behead enemies killed during their military operations but disallowed by their superiors.

Headhunting or human sacrifice was also practised by other tribes such as follows:

- Toraja community in Sulawesi used adat Ma’ Barata (human sacrifice) in Rambu Solo’ ritual which is still held until the arrival of the Hindi Dutch which is a custom to honour someone with a symbol of a great warrior and bravery in a war.[34]

- In Gomo, Sumatra, there ware megalithic artefacts where one of them is "batu pancung" (beheading stone) on which to tie any captive or convicted criminals for beheading.[35]

- One distinction was their ritual practice of head hunting, once prevalent among tribal warriors in Nagaland and among the Naga tribes in Myanmar. They used to take the heads of enemies to take on their power.

Agriculture, land tenure and economy

Traditionally, Dayak agriculture was based on actually Integrated Indigenous Farming System. Iban Dayaks tend to plant paddy on hill slopes while Maloh Dayaks prefer flat lands as discussed by King.[36] Agricultural Land in this sense was used and defined primarily in terms of hill rice farming, ladang (garden), and hutan (forest). According to Prof Derek Freeman in his Report on Iban Agriculture, Iban Dayaks used to practice twenty seven stages of hill rice farming once a year and their shifting cultivation practices allow the forest to regenerate itself rather than to damage the forest, thereby to ensure the continuity and sustainability of forest use and/or survival of the Iban community itself.[37][38] The Iban Dayaks love virgin forests for their dependency on forests but that is for migration, territorial expansion and/or fleeing enemies.

Dayaks organised their labour in terms of traditionally based land holding groups which determined who owned rights to land and how it was to be used. The Iban Dayaks practice a rotational and reciprocal labour exchange called "bedurok" to complete works on their farms own by all families within each longhouse. The "green revolution" in the 1950s, spurred on the planting of new varieties of wetland rice amongst Dayak tribes.

To get cash, Dayaks collect jungle produce for sales at markets. With the coming of cash crops, Dayaks start to plant rubber, pepper, cocoa, etc. Nowadays, some Dayaks plant oil palm on their lands while others seek employment or involve in trade.

One belief is when people die hornbills come into their souls.

The main dependence on subsistence and mid-scale agriculture by the Dayak has made this group active in this industry. The modern day rise in large-scale monocrop plantations such as palm oil and bananas, proposed for vast swathes of Dayak land held under customary rights, titles and claims in Indonesia, threaten the local political landscape in various regions in Borneo.

Further problems continue to arise in part due to the shaping of the modern Malaysian and Indonesian nation-states on post-colonial political systems and laws on land tenure. The conflict between the state and the Dayak natives on land laws and native customary rights will continue as long as the colonial model on land tenure is used against local customary law. The main precept of land use, in local customary law, is that cultivated land is owned and held in right by the native owners, and the concept of land ownership flows out of this central belief. This understanding of adat is based on the idea that land is used and held under native domain. Invariably, when colonial rule was first felt in the Kalimantan Kingdoms, conflict over the subjugation of territory erupted several times between the Dayaks and the respective authorities.

Religion and festivals

_-_Copy.jpg)

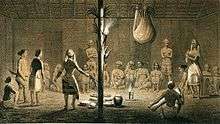

Kaharingan

The Dayak indigenous religion has been given the name Kaharingan, and may be said to be a form of animism. The name was coined by Tjilik Riwut in 1944 during his tenure as a Dutch colonial Resident in Sampit, Dutch East Indies. In 1945, during the Japanese Occupation, the Japanese referred Kaharingan as the religion of the Dayak people. During the New Order in the Suharto regime in 1980, the Kaharingan is registered as a form of Hinduism in Indonesia, as the Indonesian state only recognises 6 forms of religion i.e. Islam, Protestantism, Roman Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism respectively. The integration of Kaharingan with Hinduism is not due to the similarities in the theological system, but due to the fact that Kaharingan is the oldest belief in Kalimantan. Unlike the development in Indonesian Kalimantan, the Kaharingan is not recognised as a religion both in Malaysian Borneo and Brunei, thus the traditional Dayak belief system is known as a form of folk animism or pagan belief on the other side of the Indonesian border.[40]

The best and still unsurpassed study of a traditional Dayak religion in Kalimantan is that of Hans Scharer, Ngaju Religion: The Conception of God among a South Borneo People; translated by Rodney Needham (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1963). The practice of Kaharingan differs from group to group, but shamans, specialists in ecstatic flight to other spheres, are central to Dayak religion, and serve to bring together the various realms of Heaven (Upper-world) and earth, and even Under-world, for example healing the sick by retrieving their souls which are journeying on their way to the Upper-world land of the dead, accompanying and protecting the soul of a dead person on the way to their proper place in the Upper-world, presiding over annual renewal and agricultural regeneration festivals, etc.[41] Death rituals are most elaborate when a noble (kamang) dies.[42] On particular religious occasions, the spirit is believed to descend to partake in celebration, a mark of honour and respect to past ancestors and blessings for a prosperous future.

Iban religion

Among Iban Dayaks, their belief and way of life can be simply called the Iban religion (pengarap asal) as per Jenson's book with the same title and has been written by Benedict Sandin and others extensively. It is characterized by a supreme being in the name of Bunsu (Kree) Petara who has no parents and creates everything in this world and other worlds.[43] Under Bunsu Petara are the seven gods whose names are: Sengalang Burong as the god of war and healing, Biku Bunsu Petara as the high priest and second in command, Menjaya as the first shaman (manang) and god of medicine, Selampandai as the god of creation, Sempulang Gana as the god of agriculture and land along with Semarugah, Ini Inda/Inee/Andan as the naturally born doctor and god of justice and Anda Mara as the god of wealth.[44]

The life actions and decision-making processes of Iban Dayaks depend on divination, augury and omens. They have several methods to receive omens where omens can be obtained by deliberate seeking or chance encounters. The first method is via dream to receive charms, amulets (pengaroh, empelias, engkerabun) or medicine (obat) and curse (sumpah) from any gods, people of Panggau Libau and Gelong and any spirits or ghosts. The second method is via animal omens (burong laba) which have long-lasting effects such as from deer barking which is quite random in nature. The third method is via bird omens (burong bisa) which have short term effects that are commonly limited to a certain farming year or a certain activity at hands. The fourth method is via pig liver divination after festival celebration[45] At the end of critical festivals, the divination of the pig liver will be interpreted to forecast the outcome of the future or the luck of the individual who holds the festival.[46] The fifth but not the least method is via nampok or betapa (self-imposed isolation) to receive amulet, curse, medicine or healing.

There are seven omen birds under the charge of their chief Sengalang Burong at their longhouse named Tansang Kenyalang (Hornbill Abode), which are Ketupong (Jaloh or Kikeh or Entis) (Rufous Piculet) as the first in command, Beragai (Scarlet-rumped trogon), Pangkas (Maroon Woodpecker) on the righthand side of Sengalang Burong's family room while Bejampong (Crested Jay) as the second in command, Embuas (Banded Kingfisher), Kelabu Papau (Senabong) (Diard's Trogon) and Nendak (White-rumped shama) on the lefthand side. The calls and flights of the omen birds along with the circumstances and social status of the listeners are considered during the omen interpretations.[47]

The praying and propitiation to certain gods to obtain good omens which indicate God's favour and blessings are held in a series of three-tiered classes of minor ceremonies (bedara), intermediate rites (gawa or nimang) and major festivals (gawai) in ascending order and complexity. Any Iban Dayak will undergo some forms of simple rituals and several elaborate festivals as necessary in their lifetime from a baby, adolescent to adulthood until death. The longhouse where the Iban Dayaks stay is constructed in a unique way to function as for both living or accommodation purposes and ritual or religious practices.[48] Nearby the longhouse, there is normally a small and simple hut called langkau ampun/sukor (forgiveness/thanksgiving hut) built to place offerings to deities. Sometimes, when potentially bad omens are encountered, a small hut is quickly built and a fire is started before saying prayers to seek good outcomes.

Common among all these propitiations are that prayers to gods and/or other spirits are made by giving offerings ("piring"), certain poetic leka main and animal sacrifices ("genselan") either chickens or pigs. The number (leka or turun) of each piring offering item is based on ascending odd numbers which have meanings and purposes as below:

- piring 1 for piring jari (feeding)

- piring 3 for piring ampun (mercy) or seluwak (wastefulness spirit)

- piring 5 for piring minta (request) or bejalai (journey)

- piring 7 for piring gawai (festival) or bujang berani (brave warrior)

- piring 9 for sangkong (including others) or turu (leftover included)

Piring contains offering of various traditional foods and drinks while genselan is made by sacrificing chickens for bird omens or pigs for animal omens.

Bedara is commonly held for any general purposes before holding any rites or festivals during which a simple "miring" ceremony is done to prepare and divide piring offerings into certain portions followed by a "sampi ngau bebiau" (prayer and cleansing) poetic speeches. This most simple ceremonies have categories such as bedara matak held at the longhouse family bilek room, bedara mansau performed at the family ruai gallery, berunsur (cleansing) carried out at the tanju and river, minta ujan tauka panas (request for rain or sunniness).

The intermediate and medium-sized propitiatory rites are known as "gawa" (ritually working) with its main highlight called "nimang" (poetic incantation) that is recited by lemambang bards besides miring ceremonies. This category is smaller than or sometimes relegated from the full-scaled and thus costly festivals for cost savings but still maintaining the effectiveness to achieve the same purpose. Included in this category are "sandau ari" (mid-day ritual) held at the tanju verandah, gawai matak (unripe feast), gawa nimang tuah (Luck feast), enchaboh arong (head feast) and gawa timang beintu-intu (life caring feasts.[49]

The major festivals comprise at least seventh categories which are related to major aspects of Iban's traditional way of life i.e. agriculture, headhunting, fortune, health, death, procreation and weaving.

With paddy being the major sustenance of life among Dayaks, so the first major category comprises the agricultural-related festivals which are dedicated to paddy farming to honour Sempulang Gana who is the deity of agriculture. It is a series of festivals that include Gawai Batu (Whetstone Festival), Gawai Ngalihka Tanah (Soil Ploughing Festival), Gawai Benih (Seed Festival), Gawai Ngemali Umai (Farm Healing Festival), Gawai Matah (Harvest Initiation Festival) and Gawai Basimpan (Paddy Storing Festival). According to Derek Freeman, there are 27 steps of hill paddy farming. One common ritual activity is called "mudas" (making good) any omens found during any farming stages, especially the early bush clearing stage.

The second category includes the headhunting-related festivals to honour the most powerful deity of war, Sengalang Burong that comprises Gawai Burong (Bird Festival) and Gawai Amat/Asal (Real/Original Festival) with their successive ascending stages with most famous one being Gawai Kenyalang (Hornbill Festival). This is perhaps the most elaborate and complex festivals which can last into seven successive days of ritual inchantation by lemambang bards. It is held normally after instructed by spirits in dreams. It is performed by tuai kayau (raid leader) called bujang berani (leading warriors) and war leader (tuai serang) who are known as "raja berani" (bravery king). In the past, this festival is vital to seek divine intervention to defeat enemies such as Baketan, Ukit and Kayan during migrations into new territories.

With the suppression of headhunting, the next important and third category relates to the death-related rituals among which the biggest celebration is the Soul Festival (Gawai Antu) to honour the souls of the dead especially the famous and brave ones who are invited to visit the living for the Sebayan (Haedes) to feast and to bestow all sorts of helpful charms to the living relatives. The raja berani (brave king) can be honoured by his descendants up to three times via Gawai Antu. Other mortuary ceremonies are "beserara bungai" (flower separation) held 3 days after burial, ngetas ulit (mourning termination), berantu (Gawai Antu) or Gawai Ngelumbong (Entombing Festival).

The fourth category in term of complexity and importance is the fortune-related festivals which consist of Gawai Pangkong Tiang (Post Banging Festival) after transferring to a new longhouse, Gawai Tuah (Luck Festival) with three ascending stages to seek and to welcome lucks, and Gawai Tajau (Jar Festival) to welcome newly acquired jars.

The fifth category consists of the health-related festivals to request for curing from sickness by Menjaya or Ini Andan such as in Gawai Sakit (Sickness Festival) which is held after other smaller attempts have failed to cure the sicked persons such as begama (touching), belian (various manang rituals), Besugi Sakit (to ask Keling for curing via magical power) and Berenong Sakit (to ask for curing by Sengalang Burong) in the ascending order. Manang is consecrated via an official ceremony called "Gawai Babangun" (Manang Consecration Festival). The shaman (manang) of the Iban Dayaks have various types of pelian (ritual healing ceremony) to be held in accordance with the types of sickness determined by him through his glassy stone to see the whereabouts of the soul of the sick person.[50] Besides, Gawai Burung can also be used for healing certain difficult-to-cure sickness via magical power by Sengalang Burong especially nowadays after headhunting has been stopped. Other self-caring ritual ceremonies that are related to wellness and longevity are Nimang Bulu (Hair Adding Ceremony), Nimang Sukat (Destiny Ceremony) and Nimang Buloh Ayu (Life-Bamboo Ceremony).

The sixth category of festivals pertains to procreation. Gawai Lelabi (River Turtle Festival) is held to pray to the deity of creation called Selampadani, to announce the readiness of daughters for marriage and to solicit a suitable suitor. This is where those men with trophy head skulls become leading contenders. The wedding ceremony is called Melah Pinang (Areca nut Splitting). The god of creation Selampandai is invoked here for the fertility of the daughters to bear many children. There is a series of ritual rites from birth to adolescence of children.

_in_Tenggarong_TMnr_10005749.jpg)

The last and seventh category is Gawai Ngar (Cotton-Dyeing Festival) which is held by women who are involved in weaving pua kumbu for conventional use and ritual purposes. Ritual textiles woven by Iban women are used in the Bird Festival and in the past used to receive trophy heads. The ritual textiles have specific "engkeramba" (anthropomorphic) motifs that represent igi balang (trophy head), tiang ranyai (shrine pole), cultural heroes of Panggau and Gelong, deities and antu gerasi (demon figure).

Over the last two centuries, some Dayaks converted to Christianity, abandoned certain cultural rites and ancestors practices. All Dayak God and Deity has been labeled as mythology and converted Dayak Christian are not allowed to worship this Dayak's God and Deity indirectly making Dayak people had forgotten their original religion and ritual. Christianity was introduced by European missionaries in Borneo. Religious differences between Muslim and Christian natives of Borneo has led, at various times, to communal tensions.[51] Relations, however between all religious groups are generally good.

Many Christian Dayak has changed their name to European name but some minority still maintain their ancestors' traditional names. Since Iban has been converted to Christianity, some of them abandoned their ancestors' beliefs such as 'Miring' or celebrate 'Gawai Antu' but many celebrate only Christianized traditional festivals. However, some think there is no need to abandon their tribal beliefs to be replaced by new religions which may lead to loss of their identity and culture. They require only the appropriate modernization of their way of life to be in sync with the development and progress of contemporary time.

Despite the destruction of pagan religions in Europe by Christians, most of the people who try to conserve the Dayaks' religion are local people and certain missionaries. For example, Reverend William Howell contributed numerous articles on the Iban language, lore and culture between 1909 and 1910 to the Sarawak Gazette. The articles were later compiled in a book in 1963 entitled, The Sea Dayaks and Other Races of Sarawak.[52]

Bidayuh or Klemantan celebrates Gawai Padi (Paddy Festival)[53] or Gawai Adat Naik Dingo (Paddy Storing Festival.[54]

Society and customs

Kinship in Dayak society is traced in both lines of genealogy (tusut). Although, in Dayak Iban society, men and women possess equal rights in status and property ownership, political office has strictly been the occupation of the traditional Iban patriarch. There is a council of elders in each longhouse.

Overall, Dayak leadership in any given region, is marked by titles, a Penghulu for instance would have invested authority on behalf of a network of Tuai Rumah's and so on to a Pemancha, Pengarah to Temenggung in the ascending order while Panglima or Orang Kaya (Rekaya) are titles given by Malays to some Dayaks.

Individual Dayak groups have their social and hierarchy systems defined internally, and these differ widely from Ibans to Ngajus and Benuaqs to Kayans.

In Sarawak, Temenggong Koh Anak Jubang was the first paramount chief of Dayaks in Sarawak and followed by Tun Temenggong Jugah Anak Barieng who was one of the main signatories for the formation of Federation of Malaysia between Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak with Singapore expelled later on. He was said to be the "bridge between Malaya and East Malaysia".[15] The latter was fondly called "Apai" by others, which means father. He received no western or formal education.

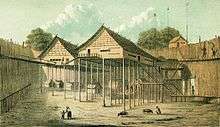

The most salient feature of Dayak social organisation is the practice of Longhouse domicile. This is a structure supported by hardwood posts that can be hundreds of metres long, usually located along a terraced river bank. At one side is a long communal platform, from which the individual households can be reached.

The Iban of the Kapuas and Sarawak have organised their Longhouse settlements in response to their migratory patterns. Iban longhouses vary in size, from those slightly over 100 metres in length to large settlements over 500 metres in length. Longhouses have a door and apartment for every family living in the longhouse. For example, a longhouse of 200 doors is equivalent to a settlement of 200 families.

The tuai rumah (long house chief) can be aided by a tuai burong (bird leader), tuai umai (farming leader) and a manang (shaman). Nowadays, each long house will have a Security and Development Committee and ad hoc committee will be formed as and when necessary for example during festivals such as Gawai Dayak.

The Dayaks are peace-loving people who live based on customary rules or adat asal which govern each of their main activities. The adat is administered by the tuai rumah aided by the Council of Elders in the longhouse so that any dispute can be settled amicably among the dwellers themselves via berandau (discussion). If no settlement can be reached at the longhouse chief level, then the dispute will escalate to a more senior leader in the region or pengulu (district chief) level in modern times and so on.

Among the main sections of customary adat of the Iban Dayaks are as follows:

- Adat berumah (House building rule)

- Adat melah pinang, butang ngau sarak (Marriage, adultery and divorce rule)

- Adat beranak (Child bearing and raising rule)

- Adat bumai and beguna tanah (Agricultural and land use rule)

- Adat ngayau (Headhunting rule) and adapt ngintu anti Pala (headskull keeping)

- Adat ngasu, berikan, ngembuah and napang (Hunting, fishing, fruit and honey collection rule)

- Adat tebalu, ngetas ulit ngau beserarak bungai (Widow/widower, mourning and soul separation rule)

- Adat begawai (festival rule)

- Adat idup di rumah panjai (Order of life in the longhouse rule)

- Adat betenun, main lama, kajat ngau taboh (Weaving, past times, dance and music rule)

- Adat beburong, bemimpi ngau becenaga ati babi (Bird and animal omen, dream and pig liver rule)

- Adat belelang (Journey rule)[55]

The Dayak life centres on the paddy planting activity every year. The Iban Dayak has their own year-long calendar with 12 consecutive months which are one month later than the Roman calendar. The months are named in accordance to the paddy farming activities and the activities in between. Other than paddy, also planted in the farm are vegetables like ensabi, pumpkin, round brinjal, cucumber, corn, lingkau and other food sources like tapioca, sugarcane, sweet potatoes and finally after the paddy has been harvested, cotton is planted which takes about two months to complete its cycle. The cotton is used for weaving before commercial cotton is traded.

Fresh lands cleared by each Dayak family will belong to that family and the longhouse community can also use the land with permission from the owning family. Usually, in one riverine system, a special tract of land is reserved for the use by the community itself to get natural supplies of wood, rattan and other wild plants which are necessary for building houses, boats, coffins and other living purposes, and also to leave living space for wild animals which is a source of meat.

Beside farming, Dayaks plant fruit trees like kepayang, dabai, rambutan, langsat, durian, isu, nyekak and mangosteen near their longhouses or on their land plots to mark their ownership of the land. They also grow plants which produce dyes for colouring their cotton treads if not taken from the wild forest. Major fishing using the tuba root is normally done by the whole longhouse as the river may take some time to recover. Any wild meat obtained will be distributed according to a certain customary law which specifies the game catcher will the head or horn and several portions of the game while others would get an equally divided portion each. This rule allows every family a chance to supply of meat which is the main source of protein.

Headhunting was an important part of Dayak culture, in particular to the Iban and Kenyah. The origin of headhunting in Iban Dayaks can be traced to the story of a chief name Serapoh who was asked by a spirit to obtain a fresh head to open a mourning jar but unfortunately he killed a Kantu boy which he got by exchanging with a jar for this purpose for which the Kantu retaliated and thus starting the headhunting practice.[27] There used to be a tradition of retaliation for old headhunts, which kept the practice alive. External interference by the reign of the Brooke Rajahs in Sarawak via "bebanchak babi" (peacemaking) in Kapit and the Dutch in Kalimantan Borneo via peacemaking at Tumbang Anoi curtailed and limited this tradition.

Apart from mass raids, the practice of headhunting was then limited to individual retaliation attacks or the result of chance encounters. Early Brooke Government reports describe Dayak Iban and Kenyah War parties with captured enemy heads. At various times, there have been massive coordinated raids in the interior and throughout coastal Borneo before and after the arrival of the Raj during Brooke's reign in Sarawak.

The Ibans' journey along the coastal regions using a large boat called "bandong" with sails made of leaves or cloths may have given rise to the term, Sea Dayak, although, throughout the 19th Century, Sarawak Government raids and independent expeditions appeared to have been carried out as far as Brunei, Mindanao, East coast Malaya, Jawa and Celebes.

Tandem diplomatic relations between the Sarawak Government (Brooke Rajah) and Britain (East India Company and the Royal Navy) acted as a pivot and a deterrence to the former's territorial ambitions, against the Dutch administration in the Kalimantan regions and client sultanates.

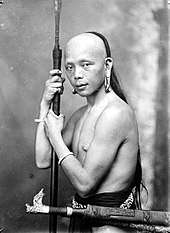

In the Indonesian region, toplessness was the norm among the Dayak people, Javanese, and the Balinese people of Indonesia before the introduction of Islam and contact with Western cultures. In Javanese and Balinese societies, women worked or rested comfortably topless. Among the Dayak, only big breasted women or married women with sagging breasts cover their breasts because they interfered with their work. Once marik empang (top cover over the shoulders) and later shirts are available, toplessness has been abandoned.[56]

Metal-working is elaborately developed in making mandaus (machetes – parang in Malay and Indonesian). The blade is made of a softer iron, to prevent breakage, with a narrow strip of a harder iron wedged into a slot in the cutting edge for sharpness in a process called ngamboh (iron-smithing).

In headhunting it was necessary to be able to draw the parang quickly. For this purpose, the mandau is fairly short, which also better serves the purpose of trailcutting in dense forest. It is holstered with the cutting edge facing upwards and at that side there is an upward protrusion on the handle, so it can be drawn very quickly with the side of the hand without having to reach over and grasp the handle first. The hand can then grasp the handle while it is being drawn. The combination of these three factors (short, cutting edge up and protrusion) makes for an extremely fast drawing-action.

The ceremonial mandaus used for dances are as beautifully adorned with feathers, as are the costumes. There are various terms to describe different types of Dayak blades. The Nyabor is the traditional Iban Scimitar, Parang Ilang is common to Kayan and Kenyah Swordsmiths, pedang is a sword with a metallic handle and Duku is a multipurpose farm tool and machete of sorts.

Normally, the sword is accompanied by a wooden shield called terabai which is decorated with a demon face to scare off the enemy. Another weapons are sangkoh (spear) and sumpit (blowpipe) with lethal poison at the tip of its laja. To protect the upper body during combat, a gagong (armour) which is made of animal hard skin such as leopards is worn over the shoulders via a hole made for the head to enter.[57]

Dayaks normally build their longhouses on high posts on high ground where possible for protection. They also may build kuta (fencing) and kubau (fort) where necessary to defend against enemy attacks. Dayaks also possess some brass and cast iron weaponry such as brass cannon (bedil) and iron cast cannon meriam. Furthermore, Dayaks are experienced in setting up animal traps (peti) which can be used for attacking enemy as well. The agility and stamina of Dayaks in jungles give them advantages. However, at the end, Dayaks were defeated by handguns and disunity among themselves against the colonialists.

Most importantly, Dayaks will seek divine helps to grant them protection in the forms of good dreams or curses by spirits, charms such as pengaroh (normally ponsonous), empelias (weapon straying away) and engkerabun (hidden from normal human eyes), animal omens, bird omens, good divination in the pig liver or by purposely seeking supernatural powers via nampok or betapa or menuntut ilmu (learning knowledge) especially kebal (weapon-proof).[58] During headhunting days, those going to farms will be protected by warriors themselves and big agriculture is also carried out via labour exchange called bedurok (which means a large number of people working together) until completion of the agricultural activity. Kalingai or pantang (tattoo) is made unto bodies to protect from dangers and other signifying purposes such as travelling to certain places.[59]

The traditional Iban Dayak male attire consists of a sirat (loincloth) attached with a small mat for sitting), lelanjang (headgear with colourful bird feathers) or a turban (a long piece of cloth wrapped around the head), marik (chain) around the neck, engkerimok (ring on thigh) and simpai (ring on the upper arms).[60] The Iban Dayak female traditional attire comprises a short "kain tenun betating" (a woven cloth attached with coins and bells at the bottom end), a rattan or brass ring corset, selampai (long scarf) or marik empang (beaded top cover), sugu tinggi (high comb made of silver), simpai (bracelets on upper arms), tumpa (bracelets on lower arms) and buah pauh (fruits on hand).[61]

The Dayaks especially Ibans appreciate and treasure very much the value of pua kumbu (woven or tied cloth) made by women while ceramic jars which they call tajau obtained by men. Pua kumbu has various motives for which some are considered sacred.[62] Tajau has various types with respective monetary values. The jar is a sign of good fortune and wealth. It can also be used to pay fines if some adat is broken in lieu of money which is hard to have in the old days. Beside the jar being used to contain rice or water, it is also used in ritual ceremonies or festivals and given as baya (provision) to the dead.[63]

The adat tebalu (widow or widower fee) for deceased women for Iban Dayaks will be paid according to her social standing and weaving skills and for the men according to his achievements in lifetime.[64][65]

Dayaks being accustomed to living in jungles and hard terrains, and knowing the plants and animals are extremely good at following animals trails while hunting and of course tracking humans or enemies, thus some Dayaks became very good trackers in jungles in the military e.g. some Iban Dayaks were engaged as trackers during the anti-confrontation by Indonesia against the formation of Federation of Malaysia and anti-communism in Malaysia itself. No doubt, these survival skills are obtained while doing activities in the jungles, which are then utilised for headhunting in the old days.

Military

Dayak war party in proas and canoes fought a battle with Murray Maxwell following the wreck of HMS Alceste in 1817 at the Gaspar Strait.[66]

The Iban Dayak's first direct encounter with the Brooke and British Navy was in 1843, during the attack by the Brooke's forces on the Batang Saribas region i.e. Padeh, Paku and Rimbas respectively. The finale of this battle was the conference at Nagna Sebuloh to sign a peace Saribas treaty to end piracy and head hunting but the natives did not sign it.[67]

In 1844, the Brooke and British Navy attacked Batang Lupar, Batang Undop and Batang Skrang to defeat the Malay shariffs and Dayak living in these regions. The Malay shariffs were easily defeated at Patusin in Batang Lupar, without a major fight despite their famous reputation and power over the native inlanders. However, during at the battle of Batang Undop, one of the Brooke and British Navy's officer i.e. Mr. Charles Wade was killed in action at the battle of Ulu Undop while chasing the Malay sheriffs upriver. Subsequently, the Brooke's Malay force headed by Datu Patinggi Ali and Mr. Steward was totally defeated by the Skrang Iban force at the battle of Kerangan Peris in the Batang Skrang region.[68]

In 1849, at the Battle of Beting Maru, sensing danger, most native boats which were returning from a sojourn at the northern Rajang river mouth landed on the Beting Maru sand bar to enable the natives escaping over land to their homelands through the Undai river while two boats of the natives acted as diversion by gallantly attacking the awaiting British man-of-war i.e. The Nenemis headed by Captain Farquhar in the dawn and retreated safely into their homeland deep in the Saribas river where they engaged the pursuing Brooke force (bala) the next day, killing two of the Brooke's Iban native entourage.[69]

Layang, the son-in-law of Libau "Rentap" was known as the first Iban slayer of a whiteman in the person of Mr. Alan Lee "Ti Mati Rugi" (Died In Vain) at the Battle of Lintang Batang in 1853, above the Skrang fort built by Brooke in 1850. The Brooke government had to launch three successive punitive expeditions against Libau Rentap to conquer his fortress known as Sadok Mount. In total, the Brooke government conducted 52 punitive expeditions against the Iban including one against the Kayan.[70]

The Iban attacked the Japanese force stationed at the Kapit fort at the end of the Second World War in 1945. The Sarawak Rangers which were mostly Dayak participated in the anti-communist insurgency during the Malayan Emergency between 1948 to 1960.[71] The Sarawak Rangers were despatched by the British to fight during the Brunei Rebellion in 1962.[72] Later, the Sarawak Rangers fought against the Indonesian forces during the Confrontation against the formation of the Federation of Malaysia along the border with Kalimantan in 1963.

Two highly decorated Iban Dayak soldiers from Sarawak in Malaysia are Temenggung Datuk Kanang anak Langkau and Sgt Ngaliguh (both awarded Seri Pahlawan Gagah Perkasa) and Awang anak Raweng of Skrang (awarded a George Cross).[73][74] So far, only one Dayak has reached the rank of a general in the Malaysian military: Brigadier-General Stephen Mundaw in the Malaysian Army, who was promoted on 1 November 2010.[75]

Malaysia's most decorated war hero is Kanang anak Langkau due to his military services helping to liberate Malaya (and later Malaysia) from the communists. The youngest of the PGB holder is ASP Wilfred Gomez of the Police Force.[76]

There were six holders of Sri Pahlawan (SP) Gagah Perkasa (the Gallantry Award) from Sarawak, and with the death of Kanang Anak Langkau, there is one SP holder in the person of Sgt. Ngalinuh.[77]

The Dayak soldiers or trackers are regarded as equivalent in bravery to the Royal Scots or the Gurkha soldiers. The Sarawak Rangers was absorbed into the British Army as the Far East Land Forces which could be deployed anywhere in the world but upon the formation of Malaysia, it becomes the Malaysian Rangers.[78]

While in Indonesia, Tjilik Riwut was remembered as he led the first airborne operation by Indonesian National Armed Forces on 17 October 1947. The team was known as MN 1001, with 17 October was celebrated annually as a special day for the Indonesian Air Force Paskhas, which traces its origins to that pioneer paratroop operation in Borneo.[79]

Politics

Kalimantan

Organised Dayak political representation in the Indonesian State first appeared during the Dutch administration, in the form of the Dayak Unity Party (Parti Persatuan Dayak) in the 1930s and 1940s. The feudal Sultanates of Kutai, Banjar and Pontianak figured prominently prior to the rise of the Dutch colonial rule. Political circumstances aside, the Dayaks in the Indonesian side actively organised under various associations beginning with the Dayak League (Sarekat Dayak) established in 1919 in Banjarmasin, to the Partai Dayak in the 1940s, which serves as an early Pan-Dayakism in Indonesia[80] and to the present day, where Dayaks occupy key positions in government.

The violent massacre of the Malay sultans, local rulers, intellectuals and politicians by the Imperial Japanese Army during the Pontianak incidents of 1943–1944 in West Borneo (present-day West Kalimantan province) created a social opportunity for the Dayak people in the West Kalimantan political and administrative system during the Orde Lama era in the Sukarno regime, as a generation of predominantly Malay administrator in West Borneo was lost during the genocide perpetrated by the Japanese. The Dayak ruling elite were mostly left unscratched due to the fact that they were then mainly located in the hinterland and because the Japanese were not interested,[80] thus giving an advantage for the Dayak leaders to fill the administrative and political position after the Indonesian independence.

In the 1955 Indonesian Constituent Assembly election, the Dayak Unity Party managed to gain:

- 146,054 votes (0.4% of the nationwide vote)

- One seat in the People's Representative Council from West Kalimantan

- 33.1% of the votes in West Kalimantan (becoming the second largest political party after Masjumi)

- the party attained 9 out of 29 seats in the West Kalimantan Regional Representative Council.

- 1.5% votes in Central Kalimantan (the party managed to obtain 6.9% of the vote in the Dayak-majority areas in the province)

The party was later disbanded after an order by the then-president Sukarno that prohibited an ethnic-based party. The members of the party were then continued their careers in other political parties. Oevaang Oerey joined the Indonesian Party (Partai Indonesia), whilst some others joined the Catholic Party (Partai Katolik).

Among the most prominent Indonesian Dayak politician is Tjilik Riwut, a member of Central Indonesian National Committee, he was honourned as the National Hero of Indonesia (Gelar Pahlawan Nasional Indonesia) in 1998 for his major contribution during the Indonesian National Revolution. He had served as the Central Kalimantan Governor between 1958 and 1967. While in 1960, Oevaang Oeray was appointed as the 3rd Governor of West Kalimantan, becoming the first governor of Dayak origin in the province. He held the office until 1966. He is also known as one of the founding fathers of Dayak Unity Party in 1945 and had been actively assisting the Brunei Revolt in 1962 during the height of Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation.

Under Indonesia, Kalimantan is now divided into five self-autonomous provinces i.e. North, West, East, South and Central Kalimantan. Under Indonesia's transmigration programme, which was initiated by the Dutch in 1905, settlers from densely populated Java and Madura were encouraged to settle in the Indonesian provinces of Borneo. The large-scale transmigration projects continued following Indonesian independence, causing social strains. In 2001 the Indonesian government ended the transmigration of Javanese settlement of Indonesian Borneo.[81]

During the killings of 1965–66 Dayaks killed up to 5,000 Chinese and forced survivors to flee to the coast and camps. Starvation killed thousands of Chinese children who were under eight years old. The Chinese refused to fight back, since they considered themselves "a guest on other people's land" with the intention of trading only.[82] 75,000 of the Chinese who survived were displaced, fleeing to camps where they were detained on coastal cities. The Dayak leaders were interested in cleansing the entire area of ethnic Chinese.[83] In Pontianak, 25,000 Chinese living in dirty, filthy conditions were stranded. They had to take baths in mud.[84] The massacres are considered a "dark chapter in recent Dayak history".[85]

From 1996 to 2003 there were violent attacks on Indonesian Madurese settlers, including executions of Madurese transmigrant communities. The violence included the 1999 Sambas riots and the Sampit conflict in 2001 in which more than 500 were killed in that year. Order was restored by the Indonesian Military.[86]

Sarawak

Dayaks political representation in Sarawak compare very poorly with their organised brethren in the Indonesian side of Borneo, partly due to the personal fiefdom that was the Brooke Rajah dominion, and possibly to the pattern of their historical migrations from the Indonesian part to the then pristine Rajang Basin. Reconstituted into British crown colony after the end of Japanese occupation in World War II, Sarawak obtained independence from the British on 22 July 1963, alongside Sabah (North Borneo) on 31 August 1963, and would join the Federation of Malaya and Singapore to form the Federation of Malaysia on 16 September 1963 under the belief of being equal partners in the "marriage" as per the 18 and 20-point agreements and the Malaysia Agreement of 1963.

Dayak political activism in Sarawak had its roots in the Sarawak National Party (SNAP) and Parti Pesaka Anak Sarawak (PESAKA) during post-independence construction in the 1960s. These parties shaped to a certain extent Dayak politics in the state, although never enjoying the real privileges and benefits of Chief Ministerial power relative to its large electorate due to their own political disunity with some Dayaks joining various political parties instead of consolidating inside one single political party. It appears that this political disunity is caused by the fact of inter-ethnic and intra-ethnic warfares among the various Dayaks ethnic groups in their past history that led to political rivalries at the loss of the whole Dayak people's power. The Dayaks need to forget their past, close ranks to unite under one umbrella party and prioritize the whole Dayak interests above all personal interests.

The first Sarawak Chief Minister was Datuk Stephen Kalong Ningkan, who was removed as the chief minister in 1966 after court proceedings and amendments to both Sarawak state constitution and Malaysian federal constitution due to some disagreements with Malaya with regards to the 18-point Agreement as conditions for the formation of Malaysia. Datuk Penghulu Tawi Sli was appointed as the second Sarawak chief minister who was a soft-spoken seat-warmer fellow and then replaced by Tuanku Abdul Rahman Ya'kub (a Melanau Muslim) as the third Sarawak chief minister in 1970 who in turn was succeeded by Abdul Taib Mahmud (a Melanau Muslim) in 1981 as fourth Sarawak chief minister. After Taib Mahmud resigned on 28 February 2014 to become the next Sarawak's governor, he appointed his brother-in-law, Adenan Satem, as the next Sarawak Chief Minister, who has in turn been succeeded by Abang Johari Openg in 2017.

Wave of Dayakism which is Dayak nationalism has surfaced at least thrice among the Dayaks in Sarawak while they are on the opposition side of politics as follows:

- Sarawak Alliance made up of SNAP and PESAKA managed to win the Sarawak Local Council Election in 1963 over the opposition pact of SUPP and PANAS, proceeding to make Stephen Kalong Ningkan as the first Sarawak Chief Minister and signing up of the Malaysia Agreement at London in 1963.[87]

- SNAP won 18 seats (with 42.70% popular vote) out of total 48 seats in Sarawak state election, 1974 while the remaining 30 seats won by Sarawak National Front. This resulted in the first Iban becoming the Opposition Leader in the Malaysian Parliament i.e. Datuk Sri Edmund Langgu being the leading Iban MP from SNAP with the SNAP president James Wong being detained under the Internal Security Act (ISA).

- PBDS (Parti Bansa Dayak Sarawak), a breakaway of SNAP in Sarawak state election in 1987 won 15 seats while its partner Permas only won 5 seats. Overall, the Sarawak National Front won 28 constituencies with PBB 14; SUPP 11 and SNAP 3.[88] In both cases, SNAP and PBDS (now both party are defunct) had joined the Malaysian National Front as the ruling coalition.

The Dayak people are still struggling to unite under one political force, perhaps due to self-enrichment of joining politics, different riverine geographical origins and past intra- and inter-tribal wars among themselves. However, the Dayak themselves fail to recognize this weakness in their political strategy. A full treatment of Dayak politics is studied by Jawan Jayum in his PhD thesis.[89]

Notable Dayaks

- Tjilik Riwut – National Hero of Indonesia and the first Governor of Central Kalimantan

- Kanang anak Langkau – National hero of Malaysia

- Stephen Kalong Ningkan – the first Chief Minister of Sarawak

- Tawi Sli – the second Chief Minister of Sarawak

- Jugah Barieng – Malaysian politician and former minister

- Pandelela Rinong – Malaysian national diving athlete

- Joseph Kalang Tie – footballer and Malaysia National Team representative

- Ahmad Koroh – The fifth Governor of Sabah

- Mohamad Adnan Robert – The sixth Governor of Sabah

- Oevaang Oeray – Third Governor of West Kalimantan

- Cornelis M.H. – The Eighth Governor of West Kalimantan

- Sugianto Sabran – The Twelfth Governor of Central Kalimantan

- Jeffrey Kitingan – President of Borneo Dayak Forum International from Sabah

- Joseph Pairin Kitingan – The former of the Chief Minister of Sabah

- Maximus Ongkili – The Malaysian Minister from Sabah

- John Daukom – Olympic Sprinter

- Suhaimi Anak Sulau – Bruneian Football Player

- Haimie Anak Nyaring – Bruneian Football Player

- Tommy Mawat Bada – Malaysian Football Player

- Henry Golding – Malaysian-born British actor

- Baru Bian - former Malaysian Minister

See also

- Bornean traditional tattooing

- Krio Dayak people and their language

- Iban people and their Iban language

- Meratus Dayak

- Hiram M. Hiller, Jr.

- Mina Susana Setra

References

- Kewarganegaraan, Suku Bangsa, Agama dan Bahasa Sehari-hari Penduduk Indonesia Hasil Sensus Penduduk 2010 [Citizenship, Ethnicity, Religion and Language Everyday, Indonesian Population Census 2010] (in Indonesian). Indonesian Central Bureau of Statistics. 2011. ISBN 978-979-064-417-5.

- "East & Southeast Asia: Brunei". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Ananta, Aris; Arifin, Evi; Hasbullah, M.; Handayani, Nur; Pramono, Wahyu (2015). Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing. p. 272. ISBN 978-981-4519-87-8. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Report for ISO 639 code: day". Ethnologue: Countries of the World. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007.

- Chalmers, Ian (2006). "The Dynamics of Conversion: the Islamisation of the Dayak peoples of Central Kalimantan" (PDF). Asian Studies Association of Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Belford, Aubrey (25 September 2011). "Borneo Tribe Practices Its Own Kind of Hinduism". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Osup, Chemaline Anak (2006). "Puisi Rakyat Iban – Satu Analisis: Bentuk Dan Fungsi" [Iban Folk Poetry – An Analysis: Form and Function] (PDF). University of Science, Malaysia (in Indonesian).

- "Use of Papan Turai by Iban". Ibanology (in Indonesian). 29 May 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Mawar, Gregory Nyanggau (21 June 2006). "Gawai". Iban Cultural Heritage. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Kerajaan Nan Sarunai". Melayu Online (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 2 May 2018. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- "Iban Migration – Peturun Iban". Iban Cultural Heritage. 26 March 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "The Orang Kaya Pemancha Dana "Bayang" of Padeh". Ibanology. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Lewis, Angeline (2019). Rajah Brooke and the ‘Pirates’ of Borneo: A Nineteenth Century Public Debate on Sea Power. UNSW Canberra: PhD thesis: School of Humanities and Social Sciences.

- "Don't Mention the Corpses: The Erasure of Violence in Colonial Writings on Southeast Asia". BiblioAsia. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- "Iban Heroes". Iban Customs & Traditions. 8 June 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- http://pariwisata.kalbar.go.id/index.php?op=deskripsi&u1=1&u2=1&idkt=4

- Heimannov, Judith M. (9 November 2007). "'Guests' can succeed where occupiers fail". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Wen-Qing, Ngoei (2019). Arc of Containment: Britain, the United States, and Anticommunism in Southeast Asia. New York: Cornell University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-1501716409.

- "This is the War in Malaya". The Daily Worker. 28 April 1952.

- Peng, Chin; Ward, Ian; Miraflor, Norma (2003). Alias Chin Peng: My Side of History. Singapore: Media Masters. pp. 302–303. ISBN 981-04-8693-6.

- Syamsuddin Haris 2005, pp. 192

- Anthony & Milner 2008, pp. 224

- S. Davidson & Henley 2007, pp. 156

- Avé, J. B. (1972). "Kalimantan Dyaks". In LeBar, Frank M. (ed.). Ethnic Groups of Insular Southeast Asia, Volume 1: Indonesia, Andaman Islands, and Madagascar. New Haven: Human Relations Area Files Press. pp. 185–187. ISBN 978-0-87536-403-2.

- Adelaar, K. Alexander (1995). Bellwood, Peter; Fox. James J.; Tryon, Darrell (eds.). "Borneo as a cross-roads for comparative Austronesian linguistics" (PDF). The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives (online ed.). Canberra, Australia: Department of Anthropology, The Australian National University: 81–102. ISBN 978-1-920942-85-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- See the language list at "Borneo Languages: Languages of Kalimantan, Indonesia and East Malaysia". Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (KITLV). Archived from the original on 9 February 2012.

- "Origin of Adat Iban: Part 3". Iban Cultural Heritage. 12 June 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Origin of Adat Iban: Part 4". Iban Cultural Heritage. 12 June 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Tradisi Kurban Manusia Di Nusantara". Ibanology (in Indonesian). 23 June 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Panglima Mujah "Buah Raya"". Ibanology (in Indonesian). 12 June 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Jerita Penyarut Batang Ai". Iban Cultural Heritage (in Indonesian). 27 June 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Robert Kenneth (26 July 2019). "Dayaks gather to mark peace treaty". New Sarawak Tribune. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "The Sampit conflict – Chronology of violence in Central Kalimantan". Discover Indonesia Online. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Tradisi Kurban Manusia Di Nusantara (Part 2 : Sulawesi)" [Human Sacrifice tradition in the Archipelago (Part 2 : Sulawesi)]. Ibanology (in Indonesian). 23 June 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Tradisi Kurban Manusia Di Nusantara (Part 3 : Sumatra)" [Human Sacrifice tradition in the Archipelago (Part 3 : Sumatra)]. Ibanology (in Indonesian). 23 June 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Victor T. King, Some aspects of Iban-Maloh contact in West Kalimantan.

- J. D. Freeman, Report on the Iban.

- J. D. Freeman, Iban Agriculture.

- "A Native of Borneo". The Wesleyan Juvenile Offering: A Miscellany of Missionary Information for Young Persons. Wesleyan Missionary Society. X: 60. June 1853. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- Baier, Martin (2007). "The Development of the Hindu Kaharingan Religion: A New Dayak Religion in Central Kalimantan". Anthropos. 102 (2): 566–570. ISSN 0257-9774. JSTOR 40389742.

- See Scharer, ibid., for many examples of shamanistic soul flight, ceremonies, etc. The most detailed study of the shamanistic ritual at funerals is by Waldemar Stöhr, Der Totenkult der Ngadju Dajak in Süd-Borneo. Mythen zum Totenkult und die Texte zum Tantolak Matei (Den Haag: Martinus Nijhoff, 1966).

- Dowlin, Nancy (1992). "Javanization of Indian Art". Indonesia. 54.

- "Perham's Sea Dyak Gods – Part I". Ibanology. 18 May 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "7 Iban gods from Raja Chenanum". Ibanology. 21 April 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Part 2: Iban augury". Iban Cultural Heritage. 27 April 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Nenung Atau Babi". Ibanology (in Indonesian). 11 June 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "The Origin Of Iban Omen Bird". Iban Cultural Heritage. 3 July 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Anggat, Stephen (3 April 2008). "The Iban Longhouse". Iban Cultural Heritage. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Leka piring Iban alu tuju ia". Ibanology (in Indonesian). 15 March 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Ibanology ‹ Log In". Ibanology. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Avé, Jan B.; King, Victor T. (1986). The People of the Weeping Forest: Tradition and Change in Borneo. Leiden, Netherlands: National Museum of Ethnology. ISBN 978-9-07131-028-7.

- Sutlive, Vinson; Sutlive, Joanne, eds. (2001). The Encyclopaedia of Iban Studies: Iban History, Society, and Culture Volume II (H-N). Kuching: The Tun Jugah Foundation. p. 697. ISBN 978-9-83405-130-3.

- Mike Reed. "Gawai Padi: A Street Party For The Rice Goddess". My One Stop Sarawak. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Lina Kunjak (30 April 2019). "Padi pun pengidup Dayak Kalimantan Barat". Suara Sarawak. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Part 1: Iban Adat Law and Custom". Iban Cultural Heritage. 22 April 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Hans Peter Duerr. "Der Mythos vom Zivilisationsprozeß 4. Der erotische Leib"

- "Gagong perengka ke beguna ba bansa Iban". Ibanology (in Indonesian). 12 June 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Pengaroh dalam budaya Iban". Ibanology (in Indonesian). 29 May 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Welcome". Borneoheadhunter. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Iban Traditional Clothing And Attire". Iban Customs & Traditions. 7 June 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- http://www.miricommunity.net/viewtopic.php?f=13&t=35112

- "Restoring Panggau Libau: a reassessment of engkeramba' in Saribas Iban ritual textiles (pua' kumbu')". Ibanology. 23 April 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Types of tajau". Ibanology. 30 May 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Iban Customary Law for Tebalu (Widow and Widower)". Ibanology. 1 March 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Kayau Indu and Iban women social status (Ranking)". Ibanology. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- No. XV. Sir Murray Maxwell, Knight". The Annual Biography and Obituary. XVI: 220–255. 1832. Retrieved on 25 July 2008. Annual Biography and Obituary, 1832 Vol. XVI, p. 239

- Spencer St John: The Life of Sir James Brooke. Chapter IV, p. 51. 1843-1844. Available at https://archive.org/stream/lifesirjamesbro01johngoog/lifesirjamesbro01johngoog_djvu.txt

- Captain Henry Keppel: The Expedition to Borneo of HMS Dido, p.110. Available at https://archive.org/stream/expeditiontobor00kellgoog/expeditiontobor00kellgoog_djvu.txt

- Spencer St John: The Life of Sir James Brooke, The Battle of Beting Marau, Chapter IX, p.174, 1849. Available at https://archive.org/stream/lifesirjamesbro01johngoog/lifesirjamesbro01johngoog_djvu.txt

- Charles Brooke: Tens Year in Sarawak, Chapter I, p. 37. Available at http://www.archive.org/stream/tenyearsinsarwa03broogoog/tenyearsinsarwa03broogoog_djvu.txt

- A. J. Stockwell; University of London. Institute of Commonwealth Studies (2004). Malaysia. The Stationery Office. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-11-290581-3.

- Abdul Majid, Harun (2007). Rebellion In Brunei - The 1962 Revolt, Imperialism, Confrontation and Oil (PDF). London, New York: I.B.Tauris. p. 125. ISBN 978 1 84511 423 7.

- "Iban Trackers". Ibanology. 3 June 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Iban Heroes Part 2". Iban Customs & Traditions. 21 January 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- The Borneo Post (2010): Stephen Mundaw becomes first Iban Brigadier General. Retrieved at https://www.theborneopost.com/2010/11/02/stephen-mundaw-becomes-first-iban-brigadier-general/. (Accessed on 18/01/2020)

- The Borneo Post (2013): PGB recipient Gomez dies battling cancer. Retrieved at https://www.theborneopost.com/2013/02/03/pgb-recipient-gomez-dies-battling-cancer/ (Accessed on 18/01/2020.

- New Sarawak Tribune (2018): Two Sarawak ‘Bravehearts’ who took on an Army of 100 CTs. Retrieved at https://www.newsarawaktribune.com.my/two-sarawak-bravehearts-who-took-on-an-army-of-100-cts/. Accessed on 18/01/2020.

- Robert Rizal Abdullah (2019). The Iban Trackers and Sarawak Rangers: 1948-1963. Available at https://ir.unimas.my/id/eprint/25997/1/The%20Iban%20Trackers%20and%20Sarawak%20Rangers.pdf. (Accessed on 18/01/2020)

- R.Rizky, T. Wibisono (2012). Mengenal Seni dan Budaya Indonesia (in Indonesian). Penebar CIF. p. 74. ISBN 9797883108.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Davidson, Jamie S. (August 2003). ""Primitive" Politics: The Rise and Fall of the Dayak Unity Party in West Kalimantan, Indonesia" (PDF). Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2014.

- M., Fearnside, Philip (1997). "Transmigration in Indonesia: Lessons from Its Environmental and Social Impacts". Environmental Management. Springer-Verlag New York Inc. 21 (4): 553–570. doi:10.1007/s002679900049. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Braithwaite, John; Braithwaite, Valerie; Cookson, Michael; Dunn, Leah (2010). Anomie and Violence: Non-truth and Reconciliation in Indonesian Peacebuilding. ANU E Press. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-921666-23-0. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

In 1967, Dayaks had expelled Chinese from the interior of West Kalimantan. In this Chinese ethnic cleansing, Dayaks were co-opted by the military who wanted to remove those Chinese from the interior who they believed were supporting communists. The most certain way to accomplish this was to drive all Chinese out of the interior of West Kalimantan. Perhaps 2,000–5,000 people were massacred (Davidson 2002:158) and probably a greater number died from the conditions in overcrowded refugee camps, including 1,500 Chinese children aged between one and eight who died of starvation in Pontianak camps (p. 173). The Chinese retreated permanently to the major towns ... the Chinese in West Kalimantan rarely resisted (though they had in nineteenth century conflict with the Dutch, and in 1914). Instead, they fled. One old Chinese man who fled to Pontianak in 1967 said that the Chinese did not even consider or discuss striking back at Dayaks as an option. This was because they were imbued with a philosophy of being a guest on other people's land with the intention of becoming a great trading diaspora.

- Hedman, Eva-Lotta E. (2008). Conflict, Violence, and Displacement in Indonesia. SOSEA-45 Series (illustrated ed.). SEAP Publications. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-87727-745-3. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

The role of indigenous Dayak leaders accounted for their "success." Regional officers and interested Dayak leaders helped to translate the virulent anti-Communist environment locally into an evident anti-Chinese sentiment. In the process, the rural Chinese were constructed as godless Communists complicit with members of the local Indonesian Communist Party ... In October 1967, the military, with the help of the former Dayak Governor Oevaang Oeray and his Lasykar Pangsuma (Pangsuma Militia) instigated and facilitated a Dayak-led slaughter of ethnic Chinese. Over the next three months, thousands were killed and roughly 75,000 more fled Sambas and northern Pontianak districts to coastal urban centers like Pontianak City and Singkawang to be sheltered in refugee and "detainment" camps. By expelling the "community" Chinese, Oeray and his gang ... intended to ingratiate themselves with Suharto's new regime.

- "Time, Volume 90, Part 2". 90. Time Inc. 1967: 37. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

Before the Indonesian Army could cool off the Dayaks, at least 250 Chinese had been slaughtered: Catholic missionaries believe that as many as 1,000 were actually killed. About 25,000 of the traumatized Chinese have descended on the sleepy West Borneo port of Pontianak, where they live in dismal squalor. The Chinese are crammed into makeshift quarters, bathe in muddy, sewage-filled canals

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Corn, Charles (1991). Distant Islands: Travels Across Indonesia. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-82374-1. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

There was a dark chapter in recent Dayak history, and it concerned the Chinese living on the island. Tribes in the lower hills had been mobilized by the Indonesian military in the mid-sixties to murder many thousands of Chinese in the

- Linder, Dianne (November 1997). "ICE Case 11: Ethnic Conflict in Kalimantan". Inventory of Conflict and Environment. Archived from the original on 18 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Sarawak Goal of Self-Government". 20 July 2015.

- Chin, James. "Sarawak's 1987 and 1991 State Elections: An Analysis of the Ethnic Vote" (PDF). Borneo Research Bulletin. Borneo Research Council. 26: 3–24.

- Jayum A. Jawan (September 1991). "Political Change and Economic Development Among the Iban of Sarawak, East Malaysia" (PDF). The University of Hull. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

Further reading

- Benedict Sandin (1967). The Sea Dayaks of Borneo Before White Rajah Rule. Macmillan.

- Derek Freeman (1955). Iban Agriculture: A Report on the Shifting Cultivation of Hill Rice by the Iban of Sarawak. H.M. Stationery Office.

- Derek Freeman (1970). Report on the Iban. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Eric Hansen (1988). Stranger in the Forest: On Foot Across Borneo. Vintage Books. ISBN 9780375724954.

- Hans Schärer (2013). Ngaju Religion: The Conception of God among a South Borneo People. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789401193467.

- Jean Yves Domalain (1973). Panjamon: I was a Headhunter. William Morrow. ISBN 9780688000288.

- Judith M. Heimann (2009). The Airmen and the Headhunters: A True Story of Lost Soldiers, Heroic Tribesmen and the Unlikeliest Rescue of World War II. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780547416069.

- Norma R. Youngberg (2000). The Queen's Gold. TEACH Services. ISBN 9781572581555.

- Peter Goullart (1965). River of the White Lily: Life in Sarawak. John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-0542-9.

- Raymond Corbey (2016). Of Jars and Gongs: Two Keys to Ot Danum Dayak Cosmology. C. Zwartenkot Art Books. ISBN 9789054500162.

- St. John, Sir Spenser (1879). The life of Sir James Brooke: rajah of Sarawak: from his personal papers and correspondence. Edinburgh & London.

- Syamsuddin Haris (2005). Desentralisasi dan otonomi daerah: desentralisasi, demokratisasi & akuntabilitas pemerintahan daerah. Yayasan Obor Indonesia. ISBN 9789799801418.

- Victor T King (1978). Essays on Borneo societies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197134344.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dayak people. |

- Tribal peoples are fighting huge hydro-electric projects that are carving up the island's rainforest

- The J. Arthur and Edna Mouw papers at the Hoover Institution Archives focuses on the interaction of Christian missionaries with Dayak people in Borneo.