Tarjadia

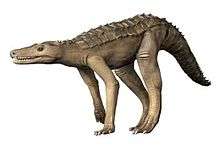

Tarjadia is an extinct genus of erpetosuchid pseudosuchian, distantly related to modern crocodilians. It is known from a single species, T. ruthae, first described in 1998 from the Middle Triassic Chañares Formation in Argentina. Partial remains have been found from deposits that are Anisian-Ladinian in age. Long known mostly from osteoderms, vertebrae, and fragments of the skull, specimens described in 2017 provided much more anatomical details and showed that it was a fairly large predator. Tarjadia predates known species of aetosaurs and phytosaurs, two Late Triassic groups of crurotarsans with heavy plating, making it one of the first heavily armored archosaurs. Prior to 2017, most studies placed it outside Archosauria as a member of Doswelliidae, a family of heavily armored and crocodile-like archosauriforms.[1][2] The 2017 specimens instead show that it belonged to the Erpetosuchidae.[3]

| Tarjadia | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Family: | †Erpetosuchidae |

| Genus: | †Tarjadia Arcucci et al. 1998 |

| Species | |

Etymology

The genus name Tarjadia is derived from Sierra de los Tarjados, the closest mountain range to the outcrops of the Los Chañares Formation where remains have been found.[4] The type species T. ruthae was named in honor of Ruth Romer, wife of the American paleontologist Alfred Romer, who led a Harvard expedition to Los Chañares in 1964 and 1965.[5] Ruth went with Alfred on the expedition and was the first woman to work in the locality.[4]

History

The first remains of Tarjadia from the Chañares Formation were mentioned by Alfred Romer in 1971. He recognized two types of osteoderms from the formation, which he tentatively attributed to the rauisuchian Luperosuchus because of their large size and similar appearance to scutes of other rauisuchians.[6] In 1990, more complete osteoderms were found from the formation, as well as associated vertebrae. Three years later, in Romer's collections at Harvard University, remains of a skull were found in association with an osteoderm that was similar to the ones described in 1971 and 1990. This allowed Tarjadia to be erected as a new genus, distinct from Luperosuchus.[4]

Specimens

The initial 1998 description of Tarjadia ruthae listed several specimens:[4]

- PULR (Museo de Paleontologia at Universidad de La Rioja) 603 (holotype):6 complete osteoderms, 3 osteoderm fragments, and at least 6 fragmentary vertebrae.

- MCZ 9319: A fragmentary skull roof and braincase, a fragment of the lower jaw, and an osteoderm fragment.

- MCZ 4076: 4 osteoderms.

In 2016, Ezcurra considered MCZ 4077 (a partial femur and osteoderm fragments), which had previously been referred to Luperosuchus and even used in a study of the histology of that genus, as actually referable to Tarjadia.[7][2] Additional specimens from various parts of the Chañares Formation were described in 2017, greatly expanding knowledge of the animal. These specimens include:[3]

- CRILAR ( Centro Regional de Investigaciones y Transferencia Tecnológica de La Rioja, Paleontología de Vertebrados)-Pv 463b: 6 osteoderm fragments.

- CRILAR-Pv 477: A partial skeleton, not including the skull.

- CRILAR-Pv 478: A partial skeleton, including a partial skull.

- CRILAR-Pv 479: The tip of a dentary, 7 vertebrae, 2 osteoderms, and rib fragments.

- CRILAR-Pv 495: A nearly complete skull and lower jaws.

- CRILAR-Pv 564: 2 vertebrae, 2 teeth, and other fragments.

- CRILAR-Pv 565: A partial skeleton including the rear part of a skull.

- CRILAR-Pv 566: A partial braincase.

Description

Osteoderms

Tarjadia has been diagnosed on the basis of its osteoderms, or bony scutes, the most common material that has been found of the genus. The paramedian osteoderms, which overlie the back to either side of the midline, are thick and rectangular. Their medial edges are serrated, allowing the two rows to suture tightly together. Smaller, more rounded osteoderms are thought to have been placed to the sides of the paramedians, although no articulated remains bearing these lateral osteoderms have been found to prove this. Both the paramedian and lateral osteoderms are deeply pitted. The paramedian osteoderms are thickest at the center and medial edges, with spongy bone between the compact outer layers.[4]

Skull

The bones of the skull table are very thick. Like the osteoderms, they are covered in coarse pitting. The surfaces of these bones also bear perforations for blood vessels, especially around the edges of the orbits, or eye sockets. The parietal bones, which lie between two openings on the skull table called supratemporal fenestrae, have a distinctive sagittal crest. On the underside of the parietals, there is a depression for the olfactory bulb of the brain, responsible for the perception of smell. An olfactory channel leads up to this depression and can be seen on the underside of the frontal bones.[4]

The fragmentary occipital area of the skull (the base of the skull) shows part of the boundary of the foramen magnum (through which the spinal cord enters the skull), channels for the vestibular system (part of the inner ear responsible for balance), and holes for the semicircular canal (also part of the vestibular system). These holes and channels are found on the supraoccipital bone. The exoccipitals and opisthotics are also known in Tarjadia, and form the paraoccipital processes, two projections for the attachments of muscles that open the lower jaw. These processes form notches that may be tympanic fossae, cavities of the middle ear.[4]

Vertebrae

The vertebrae of Tarjadia have centra, or central bodies, that are about as long as they are high. The centra have concave ventral surfaces and depressed lateral surfaces. The neural spines that project upward from the centra are laterally compressed, but have distal portions that expand into a flattened table with a groove on its upper surface. Above the flat tables of the neural arches lie the paramedian osteoderms, which also form a flat surface. Thick transverse processes on some vertebrae suggest that they make up the sacrum, the area of the spine that attaches to the pelvis. The six vertebrae known from Tarjadia probably represent the posterior dorsals, sacrals, and first caudals, comprising the end of the back vertebrae and the beginning of the tail vertebrae.[4]

Classification

Comparisons between Tarjadia and other Triassic archosaurs and archosauriforms were made in its initial 1998 description. The archosauriforms Doswellia and Euparkeria, as well as the archosauriform family Proterochampsidae, all have heavy armor over the dorsal vertebrae and existed around the same time as Tarjadia.[4] Proterochampsids do not have ornamented osteoderms like Tarjadia, nor do they have two rows of osteoderms on either side of the back (most proterochampsids, with the exception of Cerritosaurus and Chanaresuchus, have only a single row on either side). While Euparkeria has a pair of osteoderms overlying each vertebra, similar to the condition seen in Tarjadia, its osteoderms aren't ornamented. Ornamented paired osteoderms are seen as derived conditions in Doswellia and crurotarsan archosaurs.[8] Some studies have not considered Tarjadia to be a close relative of Doswellia because of differences in the structure of the vertebrae. Moreover, Tarjadia possesses a prefrontal bone in the skull which is absent in Doswellia.[4]

Among crurotarsans, vertebrae that are each overlain by a single row of pitted, paired osteoderms as in Tarjadia are seen in aetosaurs, phytosaurs, and Crocodylomorpha. Tarjadia has been distinguished from aetosaurs by its apparent lack of an anterior articular lamina (a depressed region along the front of each osteoderm), and clear differences in the skull tables. Tarjadia differs from sphenosuchians and proterosuchians, the two main Triassic crocodylomorph groups, in that its osteoderms lack any clear structures on the anterior edges of the osteoderms. In the case of sphenosuchians, the anterior edge of the osteoderm forms a process or "lappet", while in protosuchians, the anterior edge has a depressed band similar to those of aetosaurs. Out of all Triassic crurotarsans, the osteoderms of Tarjadia bear the closest resemblance to those of phytosaurs; they have a similar shape and are also heavily pitted. Moreover, the skull roof of is also pitted in phytosaurs. However, Tarjadia can be distinguished from all phytosaurs in that it has differently shaped parietal bones. The strong sagittal crest on the parietals of Tarjadia is not seen in any phytosaur.[4]

When it was first erected in 2011, the family Doswelliidae was proposed to include Doswellia, Archeopelta, and Tarjadia. Synapomorphies, or unique features of the group, include coarsely pitted and incised osteoderms and an anterior articular lamina.[1]

The phylogenetic analysis conducted by Ezcurra et al. (2017) did not confirm a close relationship between Tarjadia and Doswellia; instead, Tarjadia was recovered as an erpetosuchid pseudosuchian archosaur. The cladogram of the strict consensus tree from the study is given below.[3]

| Eucrocopoda |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Julia B. Desojo, Martin D. Ezcurra and Cesar L. Schultz (2011). "An unusual new archosauriform from the Middle–Late Triassic of southern Brazil and the monophyly of Doswelliidae". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 161 (4): 839–871. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00655.x.

- Ezcurra, Martín D. (2016-04-28). "The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms". PeerJ. 4: e1778. doi:10.7717/peerj.1778. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4860341. PMID 27162705.

- Martín D. Ezcurra; Lucas E. Fiorelli; Agustín G. Martinelli; Sebastián Rocher; M. Belén von Baczko; Miguel Ezpeleta; Jeremías R. A. Taborda; E. Martín Hechenleitner; M. Jimena Trotteyn; Julia B. Desojo (2017). "Deep faunistic turnovers preceded the rise of dinosaurs in southwestern Pangaea". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 1 (10): 1477–1483. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0305-5. PMID 29185518.

- Arcucci, A.; Marsicano, C.A. (1998). "A distinctive new archosaur from the Middle Triassic (Los Chañares Formation) of Argentina". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (1): 228–232. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011046.

- Romer, A.S. (1966). "The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. I. Introduction". Breviora. 247: 1–14.

- Romer, A.S. (1971). "The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. VIII. A fragmentary skull of a large thecodont, Luperosuchus fractus". Breviora. 373: 1–8.

- Nesbitt, Sterling; Desojo, Julia Brenda (2017-06-08). "The Osteology and Phylogenetic Position of Luperosuchus fractus (Archosauria: Loricata) from the Latest Middle Triassic or Earliest Late Triassic of Argentina". Ameghiniana. 54 (3): 261–282. doi:10.5710/AMGH.09.04.2017.3059. ISSN 1851-8044.

- Sereno, P.C. (1991). "Basal archosaurs: phylogenetic relationships and functional implications". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 11 (Suppl. 4): 1–53. doi:10.1080/02724634.1991.10011426.

External links

- Supplementary data for "Deep faunistic turnovers preceded the rise of dinosaurs in southwestern Pangaea" (2017), including geological information, anatomical details on Tarjadia ruthae, and details of a phylogenetic analysis.