Donaldsonville, Louisiana

Donaldsonville (historically French: Lafourche-des-Chitimachas[3]) is a small city in, and the parish seat of, Ascension Parish in south Louisiana, United States,[4] located along the River Road of the west bank of the Mississippi River. The population was 7,436 at the 2010 census, a decrease of more than 150 from the 7,605 tabulation in 2000. Donaldsonville is part of the Baton Rouge Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Donaldsonville, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Donaldsonville | |

The Ascension Parish Courthouse is located on Railroad Avenue in Donaldsonville | |

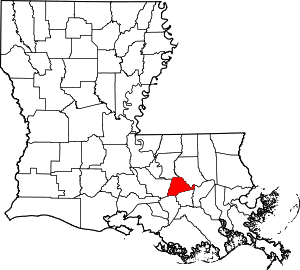

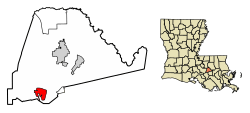

Location of Donaldsonville in Ascension Parish, Louisiana. | |

.svg.png) Location of Louisiana in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 30°6′0″N 90°59′39″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | Ascension |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Leroy Sullivan, Sr. (elected 2012) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.80 sq mi (9.84 km2) |

| • Land | 3.78 sq mi (9.78 km2) |

| • Water | 0.02 sq mi (0.06 km2) |

| Elevation | 26 ft (8 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 7,436 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 8,441 |

| • Density | 2,234.25/sq mi (862.67/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| Area code(s) | 225 |

| FIPS code | 22-21240 |

| Website | http://www.donaldsonville-la.gov/ |

Donaldsonville's historic district has what has been described as the finest collection of buildings from the antebellum era to 1933, of any of the Louisiana river towns above New Orleans.[5] Union forces attacked the city, occupying it and several of the river parishes beginning in 1862. Fort Butler was built on the west bank of the Mississippi River. The fort was successfully defended on June 28, 1863, against a Confederate attack. This battle was one of the first occasions when free blacks and fugitive slaves fought as soldiers on behalf of the Union. The fort is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

After the war, in 1868 Donaldsonville residents elected as mayor Pierre Caliste Landry, an attorney and Methodist minister; he was the first African American to be elected as mayor in the United States.[6]

History

Various cultures of indigenous peoples lived here along the Mississippi River for thousands of years prior to European colonization. The Houma and Chitimacha peoples lived in the area. During the early years of colonization, they suffered high rates of fatalities due to infectious diseases and resulting social disruption. Descendants of both tribes were federally recognized as organized groups in the 20th century and they each have reservations in Louisiana.

The French were the first Europeans to colonize the area. They named the site Lafourche-des-Chitimachas, after the regional indigenous people and the local bayou, which they gave the same name.[7] They developed agriculture in the parish, mainly as sugar cane plantations worked by African slave labor.

Acadians, expelled by the British from Acadia in 1755, began to settle in the area from 1756 to 1785, where they developed small subsistence farms. Spanish Isleños also settled here. In 1772 when the territory was under Spanish rule, the militia constructed La Iglesia de la Ascensión de Nuestro Señor Jesucristo de Lafourche de los Chetimaches (the Ascension of Our Lord Catholic Church of Lafourche of the Chitimaches) to serve the area. The region returned later to French control for a time.[8][9]

This area was included in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and became part of the United States.[8] Americans began to move into the area. Landowner and planter William Donaldson in 1806 commissioned the architect and planner, Barthelemy Lafon, to plan a new town at this site. It was renamed Donaldsonville after him.[10]

Donaldsonville was designated as the Louisiana capital (1829–1831),[11] as the result of conflict between the increasing number of Anglo-Americans, who deemed New Orleans "too noisy" and wanted to move the capital closer to their centers of population farther north in the state, and French Creoles, who wanted to keep the capital in a historically-French area.

As a result of the wealth planters gained from sugar and cotton commodity crops, they built fine mansions and other buildings in town during the antebellum years.

Civil War

In the summer of 1862, Donaldsonville was bombarded by Union forces during the American Civil War as part of the Union's effort to gain control of the Mississippi River. The Union sent gunboats to the town and warned that if shots were fired, the Union Navy would strike the area for six miles to the south and nine miles to the north and destroy every building on every plantation. Admiral David G. Farragut destroyed much of the former capital city and put Ascension Parish under martial law, extending that to other River parishes.

Historian John D. Winters, in his The Civil War in Louisiana (1963), describes the scene:

The irate naval commander, Admiral Farragut, ordered the bombardment of Donaldsonville as soon as it could be evacuated. All of the citizens of Donaldsonville . . . "left their homes and went to the bayou . . . a detachment of Yankees went to shore with fire torches in hand." The hotels, warehouses, dwellings, and some of the most valuable buildings of the town were destroyed, Plantations . . . were bombarded and set afire. . . . A citizens' committee met and decided to ask Governor Moore to keep the [Confederate] Rangers from firing on Federal boats. These attacks did no real good and brought only crude reprisals against the innocent and helped to keep the Negroes stirred up.[12]

A citizen complained that the Rangers were useless and lawless, unable or unwilling to protect Confederate property. The citizen added that the Confederate people "could not fare worse were we surrounded by a band of Lincoln's mercenary hirelings. Our homes are entered and pillaged of everything that they [Rangers] see fit to appropriate to themselves."[13]

Union forces established a base at Donaldsonville for their occupation of river parishes. They took over some plantations, running them as U.S. government plantations to supply the forces and produce cotton.[14]

Fort Butler

Many escaping slaves entered the Union lines to gain freedom. General Benjamin Butler had declared them "contrabands" of war and would not return them to slaveholders. They stayed and worked with Union forces, helping build the star-shaped Fort Butler in the town. A work of earth and wood, it was 381 feet long on the side by the Mississippi River, the other was protected by Bayou Lafourche, and the land sides by a deep moat.[14] A stockade surrounded the fort, which contained a high and thick earth parapet. There was further security from a strong log. The fort was built to accommodate 600 men, but in 1863 there were a small garrison of 180 Union men, commanded by Major Joseph Bullen of the 28th Maine; the forces were also made up of the 1st Louisiana Volunteers, a few Louisiana Native Guard convalescents, and some fugitive slaves.[14]

In June 1863, Confederate forces attacked Fort Butler at night. Led by General Tom Green, more than 1,000 Texas Rangers attacked the fort. Free blacks and fugitive slaves joined in the successful defense of the fort, in one of the first times they fought as soldiers on behalf of the Union. The New York Tribune wrote; "When action took place the negroes were stimulated to daring deeds."[14] Historian Don Frazier, wrote; "Not only did black hands build this citadel of freedom, they defended it to the death." [14] The Union kept control of the fort and ultimately won the war. It has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Post-Civil War years

After the war, Donaldsonville became the third-largest black community in the state, as more freedmen moved there to join those who had settled near Union forces for safety during the war. In 1868 the city elected the first African-American mayor in the United States, Pierre Caliste Landry,[6] a former slave who been educated in schools on a plantation owned by the Bringier family. After the war, he had advanced to become an attorney and state politician, serving in both houses of the legislature. He also became a Methodist Episcopal minister.[15]

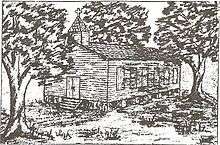

Donaldsonville is the home of one of the oldest synagogue buildings still standing in the United States.[16] The wooden structure was built in 1872 by Congregation Bikur Cholim, which disbanded in the 1940s. It is now used as an Ace Hardware store.[17] The Jewish Cemetery dates to 1800s and is located on the corner of St. Patrick Street and Marchand Drive.

Mechanization of agriculture and other changes resulted in a major loss of population in Ascension Parish from 1900 to 1930, particularly from 1920–1930. This was the period of the Great Migration, when tens of thousands of African Americans left the rural South to go for opportunities in northern and midwestern cities. Such changes also drew off business from the parish seat. Ascension Parish lost more than 16% of its population in that decade. In the Great Depression, the area struggled economically.

Historian Sidney A. Marchand, who was also an attorney, was elected as mayor of the city and state legislator during that period. He served as a state Senator and contemporary of Governor Huey Long. During the mayoral administrations of Sidney A. Marchand and his son Sidney Marchand, Jr., they directed the construction of significant infrastructure in Donaldsonville (including about 12 miles of paving, and the still-extant sewerage system). Today the Donaldsonville Historic District has what is described as the "finest collection of buildings from the pre-Civil War to 1933 period" of river towns above New Orleans.[5] It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In the 21st century, Donaldsonville is a small city with numerous historic sites. Since 2008, the River Road African American Museum, located in the city, has been included on the Louisiana African American Heritage Trail.[18] It also has parks, Civil War grounds, and shopping centers.

The official newspaper of the city is the Donaldsonville Chief, which has been published since 1871.[19]

Pelican II tragedy

The Pelican II was built at La Malbaie, Quebec, Canada, in 1992 at a cost of $15 million. It was a replica of the first ship owned by the founder of Louisiana, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville. Iberville was Le Pélican's commander in the victorious Battle of Hudson's Bay of 1697 — against three English ships.

A Louisiana company purchased Pelican II and placed it in the port of New Orleans, until 2002. It was given to the Fort Butler Foundation thereafter. The city of Donaldsonville acquired the ship from the foundation after paying $50,000 in port charges; the plan was to utilize the ship as a visitor attraction.

Pelican II sank in the Mississippi River, in November 2002. In 2004, she was refloated and moved near downtown Donaldsonville. In March of that year, she was struck by a tugboat and sank a second time. The city decided not to pay the cost of raising the ship.

In January 2008, Pelican II was struck by the tugboat Senator Stennis, which poured 30 gallons of diesel oil into the Mississippi River. The fuel leakage from the tugboat forced the closure of the river to boat traffic. City officials decided to leave the Pelican replica at the bottom of the river.[20]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.5 square miles (6.5 km2), all land. Coming upriver on the Mississippi, Donaldsonville is the point of the first expanse of land beyond the narrow natural levee. The town sits approximately 25 feet above sea level, with excellent drainage.. Donaldsonville is located where Bayou Lafourche, a distributary of the Mississippi River, formerly branched off until the entrance was dammed in 1905.[21]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 1,475 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,573 | 6.6% | |

| 1880 | 2,600 | 65.3% | |

| 1890 | 3,121 | 20.0% | |

| 1900 | 4,105 | 31.5% | |

| 1910 | 4,090 | −0.4% | |

| 1920 | 3,745 | −8.4% | |

| 1930 | 3,788 | 1.1% | |

| 1940 | 3,889 | 2.7% | |

| 1950 | 4,150 | 6.7% | |

| 1960 | 6,082 | 46.6% | |

| 1970 | 7,367 | 21.1% | |

| 1980 | 7,901 | 7.2% | |

| 1990 | 7,949 | 0.6% | |

| 2000 | 7,605 | −4.3% | |

| 2010 | 7,436 | −2.2% | |

| Est. 2019 | 8,441 | [2] | 13.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22] | |||

As of the census[23] of 2000, there were 7,605 people, 2,656 households, and 1,946 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,986.9 people per square mile (1,151.5/km2). There were 2,948 housing units at an average density of 1,157.8 per square mile (446.4/km2).

The racial makeup of the city was 29.82% White, 69.13% African American, 0.12% Native American, 0.12% Asian, 0.37% from other races, and 0.45% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.10% of the population.

There were 2,656 households, out of which 39.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.4% were married couples living together, 30.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.7% were non-families. 24.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.81 and the average family size was 3.35.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 32.1% under the age of 18, 10.6% from 18 to 24, 25.4% from 25 to 44, 19.7% from 45 to 64, and 12.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females, there were 81.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 74.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $24,084, and the median income for a family was $29,408. Males had a median income of $31,849 versus $17,528 for females. The per capita income for the city was $12,009. About 32.8% of families and 34.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 49.0% of those under age 18 and 22.2% of those age 65 or over.

Notable people

- D-D Breaux - head coach of the LSU Lady Tigers gymnastics team[24]

- Ralph Falsetta - state senator from 1975 to 1976; former mayor of Donaldsonville

- Jarvis Green - defensive end, NFL's New England Patriots

- Howard Green - defensive end, NFL

- Henry Johnson - Governor of Louisiana (1824–28)

- Plas Johnson - saxophonist

- Duncan F. Kenner (1813-1887) - built Ashland Plantation, C.S.A. ambassador to France & England, horse racer, founder of Kenner

- Joseph Aristide Landry (1817-1881), Congressman

- Pierre Caliste Landry - first African-American mayor in the US (1868)[25]

- Francis T. Nicholls - Governor of Louisiana (1877–80, 1888–92), Confederate general

- King Oliver (1881-1938) - jazz musician

- Nicholas Trist - negotiator of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo

- Sarah S. Vance - judge, U.S. District Court, Eastern District of Louisiana

- Edward Douglass White, Sr. - Governor of Louisiana (1834–38), father of the US Chief Justice

- Claiborne Williams (1868-1952) - bandleader

- Stephen Sullivan - Wide Receiver for Seattle Seahawks

See also

- Landry Tomb, in Ascension Catholic Cemetery, Donaldsonville

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Ascension Parish, Louisiana

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Cajun and Cajuns: Genealogy site for Cajun, Acadian and Louisiana genealogy, history and culture". Archived from the original on 2009-01-29. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- >"10 Best Free Things to Do in Ascension Parish" Archived 2013-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (2002). The Mississippi and the Making of a Nation: From the Louisiana Purchase to Today. National Geographic Society. p. 62. ISBN 0-7922-6913-6.

- "Old and New Names". Archived from the original on 2009-01-29. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism. "Donaldsonville Historical Marker". Archived from the original on 2012-02-29. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- Sayett. "A Eucharistic Community Since 1772". www.ascensioncatholic.com. Archived from the original on 2018-02-16. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 107. Retrieved 2016-10-14.

- "Donaldsville History - Donaldsonville, LA". www.donaldsonville-la.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-02-16. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963, ISBN 0-8071-0834-0, p. 153

- Winters, p. 153

- "Fort Butler Memorial" Archived 2013-10-19 at the Wayback Machine, Donaldsonville Chief, 16 July 2008, accessed 18 October 2013

- Shannon Burrell, "Dunn-Landry Family" Archived 2013-10-19 at the Wayback Machine, Amistad Research Center

- Gordon, Mark W. (1996). "Rediscovering Jewish Infrastructure: Update on United States Nineteenth Century Synagogues". American Jewish History. 84 (1): 11–27. doi:10.1353/ajh.1996.0013. Archived from the original on 2016-11-06. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- "Small Synagogues". Archived from the original on 2017-09-15. Retrieved 2018-11-28.

- Ron Stodghill, "Driving Back Into Louisiana’s History" Archived 2011-05-20 at the Wayback Machine, NY Times, 26 May 2008, accessed 7 July 2008

- "Donaldsonville Chief". Archived from the original on 2009-01-03. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- name=USAToday

- Martin Reuss (2 June 2004). Designing the Bayous: The Control of Water in the Atchafalaya Basin, 1800-1995. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-1-60344-632-7.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "LSUsports.net - The Official Web Site of LSU Tigers Athletics". www.lsusports.net. Archived from the original on 2018-02-16. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- Ron Stodghill, "Driving Back Into Louisiana’s History" Archived 2011-05-20 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 25 May 2008, accessed 7 July 2008

External links

- City of Donaldsonville website

- William Donaldson at Find a Grave (in New Orleans' Saint Louis Cemetery)

- Photo of Donaldsonville historical marker

- National Park Service web page on Donaldsonville Historic District

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Donaldsonville, Louisiana. |