Dnipro

Dnipro (Ukrainian: Дніпро [d⁽ʲ⁾n⁽ʲ⁾iˈprɔ] (![]()

Dnipro Дніпро | |

|---|---|

| Ukrainian transcription(s) | |

| • Romanization | Dnipro |

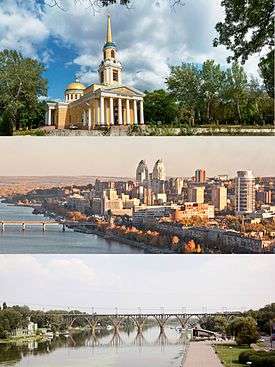

Transfiguration Cathedral, central Dnipro skyline, Merefa-Kherson bridge, Monastyrskyi Island and Dnieper river | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Location in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast | |

Dnipro Location of Dnipro in Ukraine | |

| Coordinates: 48°27′N 35°02′E | |

| Country | Ukraine |

| Oblast | Dnipropetrovsk Oblast |

| City Municipality | |

| Founded | 1776 (244 years ago) (officially[1]) |

| City Status | 1778 |

| Administrative HQ | Dnipro City Hall, 75 Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt |

| Raions | |

| Government | |

| • Type | City council, regional |

| • Mayor | Borys Filatov[2] |

| Area | |

| • City of regional significance | 409,718 km2 (158,193 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 155 m (509 ft) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • City of regional significance | |

| • Rank | 4th, UA |

| • Density | 2,411/km2 (6,240/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,000,576 |

| Demonym(s) | Dnipryanin, Dnipryanka, Dnipryani |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 49000—49489 |

| Area code(s) | +380 56(2) |

| Website | dniprorada.gov.ua |

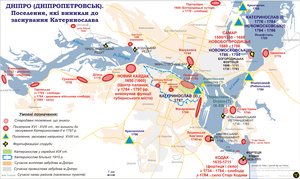

Archeological findings suggest that the first fortified town in the territory of present-day Dnipro probably dates to the mid-16th century.[1]

Known as Ekaterinoslav (Russian: Екатериносла́в, romanized: Yekaterinoslav [jɪkətʲɪrʲɪnɐˈsɫaf]; Ukrainian: Катериносла́в, romanized: Katerynoslav [kɐtɛrɪnoˈslɑu̯]) until 1925, the city was formally inaugurated by the Russian Empress Catherine the Great (Russian: Екатерина, romanized: Ekaterina - hence its then name) in 1787 as the administrative centre of the newly-acquired vast territories of imperial New Russia, including those ceded to Russia by the Ottoman Empire under the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774). Grigory Potemkin originally envisioned the city as the Russian Empire's third capital city,[9] after Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Renamed Dnipropetrovsk in 1926, it became a vital industrial centre of Soviet Ukraine, one of the key centres of the nuclear, arms, and space industries of the Soviet Union. In particular, it is home to the Yuzhmash, a major space and ballistic-missile design bureau and manufacturer. Because of its military industry, it functioned as a closed city[nb 1] until the 1990s. On 19 May 2016, Ukraine's Verkhovna Rada changed the official name of the city from Dnipropetrovsk to Dnipro.[10]

Dnipro is a powerhouse of Ukraine's business and politics and is the native city of many of the country's most important figures. Much of Ukrainian politics continues to be defined by the legacies of Leonid Kuchma, Pavlo Lazarenko and Yulia Tymoshenko, whose intermingled political careers started in Dnipropetrovsk.

History

Toponymy

Over time, Dnipro has been known by a number of names:

- Yekaterinoslav 1776–1782, reestablished 1783–1797

- Novorossiysk 1797–1802

- Yekaterinoslav 1802–1918

- Sicheslav 1918–1921 (unofficial name)[11]

- Yekaterinoslav / Katerynoslav 1918–1926

- Dnepropetrovsk / Dnipropetrovsk 1926–2016

- Dnipro 2016–present

The spelling Catharinoslav was found on some maps of the nineteenth century.[12]

In some Anglophone media the city was also known as the Rocket City.[13]

In 1918, the Central Council of Ukraine proposed to change the name of the city to Sicheslav; however, this was never finalised.[14]

In 1926 the city was renamed after Communist leader Grigory Petrovsky.[15][16] The 2015 law on decommunization required the city to be renamed,[15] and on 19 May 2016 the Ukrainian parliament passed a bill to officially rename the city to Dnipro.[10][nb 2][nb 3]

Among other names it was also known as Polovytsia.[22]

Middle Ages

A monastery was founded by Byzantine monks on Monastyrskyi Island, probably in the 9th century (870 AD). The Tatars destroyed the monastery in 1240.[23]

At the beginning of the 15th century, Tatar tribes inhabiting the right bank of the Dnieper were driven away by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. By the mid-15th century, the Nogai (who lived north of the Sea of Azov) and the Crimean Khanate invaded these lands. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Crimean Khanate agreed to a border along the Dnieper, and farther east along the Samara River (Dnieper), i.e. through what is today the city of Dnipro. It was in this time that a new force appeared: the free people, the Cossacks. They later became known as Zaporozhian Cossacks (Zaporizhia – the lands south of Prydniprovye, translate as "The Land Beyond the Weirs [Rapids]"). This was a period of raids and fighting causing considerable devastation and depopulation in that area; the area became known as the Wild Fields.

Early modern

Archeological findings strongly suggest that the first fortified town in what is now Dnipro was probably built in the mid-16th century.[1][24] In 1635, the Polish Government built the Kodak Fortress above the Dnieper Rapids at Kodaky (on the south-eastern outskirts of modern Dnipro), partly as a result of rivalry in the region between Poland, Turkey and Crimean Khanate,[24] and partly to maintain control over Cossack activity (i.e. to suppress the Cossack raiders and to prevent peasants moving out of the area).[25] On the night of ¾ August 1635, the Cossacks of Ivan Sulyma captured the fort by surprise, burning it down and butchering the garrison of about 200 West European mercenaries under Jean Marion.[25] The fort was rebuilt by French engineer Guillaume Le Vasseur de Beauplan[26] for the Polish Government in 1638, and had a mercenary garrison.[25] Kodak was captured by Zaporozhian Cossacks on 1 October 1648, and was garrisoned by the Cossacks until its demolition in accordance with the Treaty of the Pruth in 1711.[27] The ruins of the Kodak are visible now. There is currently a project to restore it and create a tourist centre and park-museum.[27]

Following the Treaty of Andrusovo, the lands of Zaporizhian Sich (around Kodak fortress) were under a condominium between the Russian Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Rzeczpospolita relinquished its control over the area with signing of the 1686 Treaty of Perpetual Peace and, thus, handing over Zaporizhia to Russia.

In 1688 Zaporozhian Cossacks and Tatar forces unsuccessfully tried to destroy the Russian troops in the town's Bohorodytsia Fortress (built for the Russian Tsar) but ended up destroying the unprotected lower town only.[1] Cossacks in 1711 forced the Russians troops out of the town under the Treaty of the Pruth; this time in an alliance with the Tatars and the Ottoman Empire.[1] Two fortresses on territory of the future Ukrainian metropolis, Kodak Fortress and Bohorodytsia Fortress (on territory of Samar), were razed in accordance to the Russian treaty.

In the mid-1730s Russians troops returned to the Bohorodytsia Fortress.[1]

The Zaporozhian village of Polovytsia was founded in the late-1760s, between the settlements of Stari (Old) and Novi (New) Kodaky. It was located at the present centre of the city to the West to district of Central Terminal and the Ozyorka farmers market.[28]

Cossacks and the Russian army had fought against the Ottoman Empire for control of this area in the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774). The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca ended this war in July 1774, and in May 1775 the Russian army destroyed the Zaporozhian Sich, thus eliminating the political autonomy of Cossacks. In 1775, Prince Grigori Potemkin was appointed governor of Novorossiya, and after the destruction of the Zaporozhian Sich, he started founding cities in the region and encouraging foreign settlers.

Establishment of Catherine's city

Prior to 1926 the city currently called Dnipro was known as Ekaterinoslav, which could be approximately rendered as "the glory of Catherine", with reference to Catherine the Great, who reigned as Empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. (The Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) connects city traditions with the name of Saint Catherine of Alexandria (c. 287 to c. 305).[29][30] According to one account, the city was founded in 1787[1] (the official founding year was set to 1776 in 1976 in an effort to please the general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Leonid Brezhnev[1]) as the administrative centre of Russia's newly re-established Azov Governorate (founded in 1775).

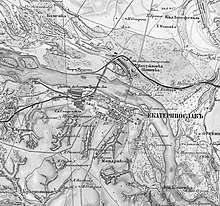

The original town of Yekaterinoslav was founded in 1777 by the Azov Governor Vasiliy Alexeyevich Chertkov (in office 1775-1781) on the orders of Grigory Potemkin,[31] not in the current location, but at the confluence of the River Samara with the Kilchen River near Loshakivka, north of the Dnieper.[31] The city was named in honor of the Russian Empress Catherine the Great.[31] By 1782 the city had a population of 2,194.[31] However the site had been badly chosen - spring waters transformed the city into a bog.[28][31] The settlement there was later renamed Novomoskovsk (today Novomoskovsk, Ukraine).[32]

On 22 January 1784 Catherine the Great signed an Imperial Ukase stating the following, "the gubernatorial city under name of Yekaterinoslav to be by better convenience on the right bank of Dnieper near Kaidak" ("губернскому городу под названием Екатеринослав быть по лучшей удобности на правой стороне реки Днепр у Кайдака…").[31] Construction started on the site of Zaporizhian sloboda Polovytsia that had existed at least since 1740s.[31] Here were the wintering estates of the Cossack officers Mykyta Korzh, Lazar Hloba, and others.[31]

The ceremonial laying the foundation of Yekaterinoslav as the centre of the Yekaterinoslav Viceroyalty took place on 20 May 1787 on the hill where Zhovtneva Square is now.[31] The population of Yekaterinoslav-Kil'chen were (according to some sources) transferred to the new site. Potemkin had extremely ambitious plans for the city. In drafting and construction of the city took part prominent Russian architects Ivan Starov, Vasily Stasov, Andreyan Zakharov.[31] The city's development started along Dnieper from two opposite ends divided by deep ravines.[31] It was to be about 30 by 25 km (19 by 16 mi) in size, and included[28] Transfiguration Cathedral (the claim that it was intended as the largest in the world probably results from confusing Potemkin's reference to San Paulo-fuori-le-mura in Rome with St Peter's Basilica.[32]); university (never built); botanical garden on Monastyrskyi Island and wide straight avenues through the city. In 1790 at the hilly part of the city was built the Potemkin's princely palace on draft of Ivan Starov.[31] The cathedral's foundation stone was laid by Empress Catherine II and Austrian Emperor Joseph II, during Catherine's Crimean journey[33] on 20 May [O.S. 9 May] 1787, which was heralded as the official date of founding the city. Nevertheless, the cathedral as originally designed was never to be built. The site for the Potemkin palace was bought from retired Cossack yesaul (colonel) Lazar Hloba, who owned much of the land near the city. Part of Lazar Hloba's gardens still exist and are now called Hloba Park.[28]

A combination of yet another Russo-Turkish war that broke out later in 1787, bureaucratic procrastination, defective workmanship, and theft resulted in what was built being less than originally planned. Construction stopped after the death of Potemkin (1791) and of his sponsor, Empress Catherine (1796), who was succeeded by her son Emperor Paul I - known for his open antipathy to his mother's policies and undertakings. Plans were reconsidered and scaled back. The size of the cathedral was reduced, and construction finished only in 1835.

The origin of industrial centre

In 1794 in the city started to operate a big treasury-sponsored manufacture that consisted of two factories: cloth factory that was transferred here from town of Dubrovny Mogilev Governorate along with workers and serf-peasants and silk-stockings factory that was brought from village of Kupavna near Moscow.[31] The workers for silk stockings factory were bought at an auction for 16,000 rubles.[31] In 1797 at the cloth factory worked 819 permanent workers among which were 378 women and 115 children.[31] At the stockings factory a bigger portion of workers consisted of women.[31] Those workers lived in barracks that were located where today is Lakes (Ozerna) Square and along Dnieper embankment where later appeared a factory sloboda.[31] To those manufactures were also assigned 1,186 men of rural population who were settled along Mokra Sura River where later appeared Sursko-Lytovska (Sura-Lithuanian) Sloboda.[31] Most of buildings for those factories were built out of wood on a draft of Russian architect Fyodor Volkov.

Work conditions at those factories as well as during initial development of the city were harsh.[31] People were dying in hundreds from cold, famine, and back-breaking work.[31] Even Potemkin himself was forced to admit that fact.[31] The factories did not always pay their workers on time and often underpay.[31] The factory report of 26 March 1797 indicated about "inadequate" accommodations of workers dwellings.[31] It was a hastily assembled housing suitable only for summertime.[31]

From 1797 to 1802,[31] the city was renamed as Novorossiysk by the Russian Emperor Paul I of Russia,[31] when it served as a centre of the recreated Novorossiya Governorate, and subsequently, till 1925, of the Ekaterinoslav Governorate.

The city business in majority was based in processing of agricultural raw materials.[31] Only in 1832 in the city was founded a small iron-casting factory of Zaslavsky, which became the first company of its kind.[31] The factory only employed 15 workers.[31]

Despite the bridging of the Dnieper in 1796 and the growth of trade in the early 19th century, Ekaterinoslav remained small until the 1880s, when the railway was built and industrialization of the city began.[34] The boom was caused by two men: John Hughes, a Welsh businessman who built an iron works at what is now Donetsk (then Yuzovka) in 1869–72, and developed the Donetsk coal deposits;[28] and the Russian geologist Alexander Pol, who discovered the Kryvyi Rih iron ore in 1866, during archaeological research.[28]

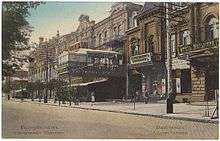

The Donetsk coal was necessary for smelting pig-iron from the Kryvyi Rih ore, producing a need for a railway to connect Yozovka with Kryvyi Rih. Permission to build the railway was given in 1881, and it opened in 1884. The railway crossed the Dnieper at Ekaterinoslav. The city grew quickly; new suburbs appeared: Amur, Nyzhnodniprovsk and the factory areas developed. In 1897, Ekaterinoslav became the third city in the Russian Empire to have electric trams. The Higher Mining School opened in 1899, and by 1913 it had grown into the Mining Institute.[28]

Russian defeat in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, among other things, resulted in widespread revolts against the government in many places of Russia, Ekaterinoslav being one of the major hot spots.[35] Dozens of people were killed and hundreds wounded. There was a wave of anti-Semitic attacks.[28]

From 1902 to 1933, the historian of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, Dmytro Yavornytsky, was Director of the Dnipro Museum, which was later named after him. Before his death in 1940, Yavornytsky wrote a History of the City of Ekaterinoslav, which lay in manuscript for many years. It was only published in 1989 as a result of the Gorbachev reforms.

Ukrainian War of Independence

After the Russian February revolution in 1917, Ekaterinoslav became a city within autonomy of Ukrainian People's Republic under Tsentralna Rada government. In November 1917, the Bolsheviks led a rebellion and took power for a short time. On 5 April 1918 the German army took control of the city.[37] And according to the February 1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk between the Ukrainian People's Republic and the Central Powers it became part of the Ukrainian People's Republic.[38] The city experienced occupation by German and Austrian-Hungarian armies that were allies of Ukrainian Hetman Pavlo Skoropadskyi and helped him to keep authority in the country.

In the time of the Ukrainian Directorate government, with its dictator Symon Petlura, the city had periods of uncertain power. At times the anarchists of Nestor Makhno held the city, and at others Denikin's Volunteer Army. Military operations of the Red Army, which came in from the North, captured the city in 1919, and despite attempts by Russian General Wrangel in 1920, he was unable to reach Yekaterinoslav. The War ended the following year.

Soviet Union and Nazi rule

The city was renamed after the Communist leader of Ukraine Grigory Petrovsky in 1926.[16][39] Petrovsky was later involved in the organization of the Holodomor.[16]

Dnipropetrovsk was under Nazi occupation from 26 August 1941[40] to 25 October 1943.[41] As part of the Holocaust, in February 1942 Einsatzgruppe D reduced the city's Jewish population from 30,000 to 702 over the course of four days.[42]

Closed city

As early as July 1944, the State Committee of Defence in Moscow decided to build a large military machine-building factory in Dnipropetrovsk on the location of the pre-war aircraft plant. In December 1945, thousands of German prisoners of war began construction and built the first sections and shops in the new factory. This was the foundation of the Dnipropetrovsk Automobile Factory.

Joseph Stalin suggested special secret training for highly qualified engineers and scientists to become rocket construction specialists.

In 1954 the administration of this automobile factory opened a secret design office with the name "Southern" (konstruktorskoe biuro Yuzhnoe – in Russian) to construct military missiles and rocket engines. Hundreds of talented physicists, engineers and machine designers moved from Moscow and other large cities in the Soviet Union to Dnipropetrovsk to join this "Southern" design office. In 1965, the secret Plant No. 586 was transferred to the Ministry of General Machine-Building of the USSR. The next year this plant officially changed its name to "the Southern Machine-building Factory" (Yuzhnyi mashino-stroitel’nyi zavod) or in abbreviated Russian, simply Yuzhmash.

The first "General Constructor" and head of the "Southern" design office was Mikhail Yangel, a prominent scientist and outstanding designer of space rockets, who managed not only the design office, but the entire factory from 1954 to 1971. Yangel designed the first powerful rockets and space military equipment for the Soviet Ministry of Defence.

In 1951 the Southern Machine-building Factory began manufacturing and testing new military rockets for the battlefield. The range of these first missiles was only 270 kilometres (168 miles). By 1959 Soviet scientists and engineers developed new technology, and as a result, the "Southern" design office (KBYu – as abbreviated in Russian) started a new machine-building project making ballistic missiles. Under the leadership of Yangel, KBYu produced such powerful rocket engines that the range of these ballistic missiles was practically without limits. During the 1960s, these powerful rocket engines were used as launch vehicles for the first Soviet space ships. During Makarov's directorship, Yuzhmash designed and manufactured four generations of missile complexes of different types. These included space launch vehicles Kosmos, Tsyklon-2, Tsyklon-3 and Zenit. Under the leadership of Yangel's successor, V. Utkin, the KBYu created a unique space-rocket system called Energia-Buran. Yuzhmash engineers manufactured 400 technical devices that were launched in artificial satellites (Sputniks). For the first time in the world space industry, the Dnipropetrovsk missile plant organised the serial production of space Sputniks. By the 1980s, this plant manufactured 67 different types of space ships, 12 space research complexes and four defence space rocket systems.

These systems were used not only for purely military purposes by the Ministry of Defence, but also for space research, for global radio and television networks, and for ecological monitoring. Yuzhmash initiated and sponsored the international space program of socialist countries, called Interkosmos.

On the eve of the collapse of the Soviet Union, KBYu had 9 regular and corresponding members of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, 33 full professors and 290 scientists holding a PhD They awarded scientific degrees and presided over a prestigious graduate school at KBYu, which attracted talented students of physics from all over the USSR. More than 50,000 people worked at Yuzhmash. At the end of the 1950s, Yuzhmash became the main Soviet design and manufacturing centre for different types of missile complexes. The Soviet Ministry of Defence included Yuzhmash in its strategic plans. The military rocket systems manufactured in Dnipropetrovsk became the major component of the newly born Soviet Missile Forces of Strategic Purpose.

According to contemporaries, Yuzhmash was a separate entity inside the Soviet state. After a long period of competition with the Moscow centre of rocket construction of V. Chelomei (a successor of Koroliov), Yuzhmash rocket designs won in 1969. Since that time leaders of the Soviet military industrial complex preferred Yuzhmash rocket models. By the end of the 1970s, this plant became the major centre for designing, constructing, manufacturing, testing and deploying strategic and space missile complexes in the Soviet Union. The general designer and director of Yuzhmash supervised the work of numerous research institutes, design centres and factories all over the Soviet Union from Moscow, Leningrad and Kiev, to Voronezh and Yerevan. The Soviet state provided billions of Soviet rubles to finance Yuzhmash projects.

Officially, Yuzhmash manufactured agricultural tractors and special kitchen equipment for everyday needs, such as mincing-machines or juicers for civilian Soviet households. In official reports for the general audience there was no information about the production of rockets or spaceships. However, hundreds of thousands of workers and engineers in the city of Dnipropetrovsk worked in this plant and members of their families (up to 60% of the city population) knew about the "real production" of Yuzhmash. This missile plant became a significant factor in the arms race of the Cold War. This is why the Soviet government approved of the KGB's secrecy about Yuzhmash and its products. According to the Soviet government's decision, the city of Dnipropetrovsk was officially closed to foreign visitors in 1959. No citizen of a foreign country (even of the socialist ones) was allowed to visit the city or district of Dnipropetrovsk. After the late 1950s ordinary Soviet people called Dnipropetrovsk "the rocket closed city." Only during perestroika was Dnipropetrovsk opened to foreigners again in 1987.

Contemporary

In June 1990,[43] the women's department of Dnipropetrovsk preliminary prison was destroyed in prison riots. In the ten years that followed, women under investigation (i.e. not convicted) in Dnipropetrovsk oblast were either held in Preliminary Prison 4 in Kryvyi Rih or in "detention blocks" in Dnipropetrovsk; this contravened Ukrainian Law "On preliminary incarceration". Journeys from Kryviy Rih took up to six hours in special railway carriages with grated windows. Some prisoners had to do this 14 or 15 times. After complaints by the ombudsman (Nina Karpacheva) the head of the State prison department of Ukraine (Vladimir Levochkin) arranged that finances were given for the provision of women's cells in Dnipropetrovsk Preliminary Prison, making the lives of the 15,000 unconvicted women-detainees easier from August 2000.[44]

In 2005, the most powerful representative of the "Dnipropetrovsk Faction" in Ukrainian politics was Leonid Kuchma, the former President of Ukraine and former senior manager of Yuzhmash.

In June and July 2007, Dnipropetrovsk experienced a wave of random serial killings that were dubbed by the media as the work of the "Dnipropetrovsk maniacs".[45] In February 2009, three youths were sentenced for their part in 21 murders, and numerous other attacks and robberies.[46]

On 27 April 2012, four bombs exploded near four tram stations in Dnipropetrovsk, injuring 26 people.

During the 2014 Euromaidan regional state administration occupations protests against President Viktor Yanukovych were also held in Dnipropetrovsk.[47] On 26 January, 3,000 anti-Yanukovych activists attempted to capture the local regional state administration building, but failed.[48][49][50][51][52] This was mirrored by instances of rioting[53] and the beating up of anti-Yanukovych protesters.[54][55] Dnipropetrovsk Governor Kolesnikov called the anti-Yanukovych protesters 'extreme radical thugs from other regions'.[56] Two days later about 2,000 public sector employees called an indefinite rally in support of the Yanukovych government.[57] Meanwhile, the government building was reinforced with barbed wire.[57][58][59] On 19 February 2014 there was an anti-Yanukovych picket near the Regional State Administration.[60] On 22 February 2014 after another anti-Yanukovych picket near the Regional State Administration Dnipropetrovsk Mayor Ivan Kulichenko left Yanukovych's Party of Regions "for peace in the city".[61] Simultaneously the Dnipropetrovsk City Council vowed to supports "the preservation of Ukraine as a single and indivisible state", although some members called for separatism and for federalization of Ukraine.[61] The City Council also decided to rename city's Lenin Square into "Heroes of Independence Square".[61] In the Regional State Administration building protesters dismantled Viktor Yanukovych portrait.[61] 22 February 2014 was also the day that Yanukovych was ousted out of office, after violent events in Kiev.[62]

According to media reports, Dnipropetrovsk was relatively quiet during the 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine, with pro-Russian Federation protestors outnumbered by those opposing outside intervention.[63][64] In March 2014 the city's Lenin Square was renamed "Heroes of Independence Square" in honor of the people killed during Euromaidan.[64][65] The statue of Lenin on the square was removed.[64][66] In June 2014 another Lenin monument was removed and replaced by a monument to the Ukrainian military fighting the War in Donbass.[67][68]

In order to comply with the 2015 decommunization law the city was renamed Dnipro in May 2016, after the river that flows through the city.[10][15]

Government

The City of Dnipro is governed by the Dnipro City Council. It is a city municipality that is designated as a separate district within its oblast.

Administratively, the city is divided into "districts in city" ("raiony v misti"). Presently, there are 8 of them. Aviatorske, an urban-type settlement located near the Dnipropetrovsk International Airport, is also a part of Dnipro Municipality.

The City Council Assembly makes up the administration's legislative branch, thus effectively making it a city 'parliament' or rada. The municipal council is made up of 12 elected members, who are each elected to represent a certain district of the city for a four-year term. The current council was elected in 2015. The council has 29 standing commissions which play an important role in the oversight of the city and its merchants.

Dnipro has five single-mandate parliamentary constituencies entirely within the city, through which members of parliament (MPs) are elected to represent the city in Rada. At the last (2014) general election, were won by PPB and independent candidates with. In multimember districts city voted for Opposition Bloc, union of all political forces that did not endorse Euromaidan.

In the last decades the city has generally supported candidates belonging to the Party of Regions and (in the 1990s) Communist Party of Ukraine in national and local elections. There was the same situation in presidential elections, with strong support for Leonid Kuchma and Viktor Yanukovych. After the 2014 events of Euromaidan, which included mass demonstrations and clashes in the central city, Regions lost its influence, and Dnipropetrovsk supported Petro Poroshenko. In the 2015 Ukrainian local elections Borys Filatov of the patriotic UKROP[69] was elected Mayor of Dnipro.[70]

Dnipro is also the seat of the oblast's local administration controlled by the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast Rada. The governor of the oblast is the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast Rada speaker, appointed by the President of Ukraine.

Subdivisions

| Code | Name of raion | Year of creation | Area (hectares) | Population in 2006 | Most important streets and areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amur-Nyzhnodniprovskyi | 1918/1926 | 7,162.6 | 154,400 | Streets: Vulytsia Peredova, Prospekt Manuilyvskyi, Prospekt Slobozhanskyi, Vulytsia Kalynova, Vulytsia Vidchyznyana, Vulytsia Yantarna, Donetske Shose Areas: Amur, Nizhnedneprovsk, Kirillovka, Borzhom, Sultanovka, Sakhalin, Berezanovka, Sonyachnyi Estate, Frunzensky Estate, Livoberezhnyi Estates 1 and 2. |

| 2 | Shevchenkivskyi | 1973 | 3,145.2 | 152,000 | Streets: Prospekt Bohdana Khmelnytskoho, Vulytsia Mykhaila Hrushevskoho/Vulytsia Sichovykh Striltsiv, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, Vulytsia Sviatoslava Khorobroho, Zaporizke Shosse, Vulytsia Krotova Areas: Tsentr, Slobodka, Razvlika-Podstantsiya, 12th Kvartal, Topol Estate 1, 2 and 3, Mirnyi, Danila Nechaya. |

| 3 | Sobornyi | 1935 | 4,409.3 | 169,500 | Streets: Prospekt Gagarina, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, Sicheslavska naberezhna/Peremogy, Vulytsia Volodymyra Vernadskoho, Vulytsia Gogolya, Vulytsia Chesnyshevskogo, Vulytsia Kosmichna, Vulytsia Yasnopolyanska Areas: Tsentr, Narodny (Lagerny), Podstantsiya, Sokol Estate 1 and 2, Peremoga Estate 1–6, Mandrykivka, Lotskamenka, Tonnelnaya Balka, Monastyrskyi Ostriv, Kosa. |

| 4 | Industrialnyi | 1969 | 3,267.9 | 132,700 | Streets: Prospekt Slobozhanskyi, Vulytsia Petra Kalnyshevskoho, Vulytsia Osinnya, Vulytsia Baykalska, Vulytsia Vinokurova Areas: Klochko, Samarovka (Yozhefstal), Oleksandrivka, Livoberezhnyi Estate 1–3; Nizhnedniprovskyi Pipe Production Plant. |

| 5 | Tsentralnyi | 1932 | 1,040.3 | 67,200 | Streets: Vulytsia Staryi Shlyakh, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, Prospekt Pushkina, Vulytsia Yaroslava Mudroho, Vulytsia Voitsekhovycha, Vulytsia Korolenko, Prospekt Bohdana Khmelnytskoho, Staromostova Square Areas: Bus Station, River Station and port. |

| 6 | Chechelivskyi | 1933 | 3,589.7 | 120,600 | Vulytsia Robitnycha, Prospekt Nigoyana, Prospekt Pushkina, Vulytsia Kirovozhska, Vulytsia Makarova, Vulytsia Titova, Vulytsia Budivelnykiv, Prospekt Bohdana Khmelnytskoho Areas: Chechelovka, Aptekarska Balka/Shlyakhova, 12th Kvartal, Krasnopole, Southern Machine-building Plant. |

| 7 | Novokodatskyi | 1920 | 10,928 | 157,400 | Streets: Vulytsia Naberezhna Zavodska, Prospekt Nigoyana, Prospekt Mazepy, Prospekt Metallurgov, Vulytsia Kyivska, Vulytsia Kommunarovska, Prospekt Svobody, Vulytsia Brativ Trofimovykh, Vulytsia Mostova, Vulytsia Mayakovskogo, Vulytsia Budennogo Areas: Toromske, Dievka, Sukhachevka, Yasny, Novi Kaydaki, Sukhii Ostriv, Chervonij Kamin Estate, Kommunar Estate, Parus Estate 1 and 2, Zakhidnyi Estate, Petrovsky Factory and other metallurgical plants. |

| 8 | Samarskyi | 1977 | 6,683.4 | 77,900 | Streets: Vulytsia Marshala Malinovskogo, Vulytsia Molodogvardiiska, Vulytsia Semaforna, Vulytsia Tomska, Vulytsia Kosmonavta Volkova, Vulytsia 20 rokiv Peremogy, Vulytsia Gavanska Areas: Chapli, Pridniprovsk, Igren, Rybalske (Fischersdorf), Odinkovka, Shevchenko, Pivnichnyi Estate, Nizhniodniprovsk-Vuzol. |

Five of the eight city districts were renamed late November 2015 to comply with decommunization laws.[71]

Geography

The city is built mainly upon both banks of the Dnieper, at its confluence with the Samara River. In the loop of a major meander, the Dnieper changes its course from the north west to continue southerly and later south-westerly through Ukraine, ultimately passing Kherson, where it finally flows into the Black Sea.

Nowadays both the north and south banks play home to a range of industrial enterprises and manufacturing plants. The airport is located about 15 km (9.3 mi) south-east of the city.

The centre of the city is constructed on the right bank which is part of the Dnieper Upland, while the left bank is part of the Dnieper Lowland. The old town is situated atop a hill that is formed as a result of the river's change of course to the south. The change of river's direction is caused by its proximity to the Azov Upland located southeast of the city.

One of the city's streets, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, links the two major architectural ensembles of the city and constitutes an important thoroughfare through the centre, which along with various suburban radial road systems, provides some of the area's most vital transport links for both suburban and inter-urban travel.

Climate

Under the Köppen–Geiger climate classification system, Dnipro has a humid continental climate (Dfa/Dfb).[72] Snowfall is more common in the hills than at the city's lower elevations. The city has four distinct seasons: a cold, snowy winter; a hot summer; and two relatively wet transition periods. However, according to other schemes (such as the Salvador Rivas-Martínez bioclimatic one), Dnipro has a Supratemperate bioclimate, and belongs to the Temperate xeric steppic thermoclimatic belt, due to high evapotranspiration.[73] During the summer, Dnipro is very warm (average day temperature in July is 24 to 28 °C (75 to 82 °F), even hot sometimes 32 to 36 °C (90 to 97 °F). Temperatures as high as 36 °C (97 °F) have been recorded in May. Winter is not so cold (average day temperature in January is −4 to 0 °C (25 to 32 °F), but when there is no snow and the wind blows hard, it feels extremely cold. A mix of snow and rain happens usually in December.

The best time for visiting the city is in late spring (late April and May), and early in autumn: September, October, when the city's trees turn yellow. Other times are mainly dry with a few showers.[74]

"However, the city is characterized with significant pollution of air with industrial emissions."[75] The "severely polluted air and water" and allegedly "vast areas of decimated landscape" of Dnipro and Donetsk are considered by some to be an environmental crisis.[76] Though exactly where in Dnipropetrovsk these areas might be found is not stated.[76]

| Climate data for Dnipro (1981–2010, extremes 1948–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.3 (54.1) |

17.5 (63.5) |

24.1 (75.4) |

31.8 (89.2) |

36.1 (97.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

39.8 (103.6) |

40.9 (105.6) |

36.5 (97.7) |

32.6 (90.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

40.9 (105.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1.0 (30.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

6.0 (42.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.7 (78.3) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.6 (81.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

0.2 (32.4) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.6 (25.5) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

1.8 (35.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.1 (21.0) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

10.6 (51.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.8 (62.2) |

15.9 (60.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

5.0 (41.0) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

4.9 (40.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −30.0 (−22.0) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

−19.2 (−2.6) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

3.9 (39.0) |

5.9 (42.6) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−17.9 (−0.2) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

−30.0 (−22.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 45 (1.8) |

43 (1.7) |

43 (1.7) |

38 (1.5) |

44 (1.7) |

64 (2.5) |

59 (2.3) |

43 (1.7) |

41 (1.6) |

39 (1.5) |

46 (1.8) |

45 (1.8) |

552 (21.7) |

| Average rainy days | 9 | 8 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 132 |

| Average snowy days | 16 | 15 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 15 | 64 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 88 | 85 | 79 | 67 | 62 | 66 | 65 | 62 | 70 | 77 | 87 | 88 | 75 |

| Source: Pogoda.ru.net[77] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Dnipro is a primarily industrial city of around one million people; in being such it has developed into a large urban centre over the past few centuries to become, today, Ukraine's fourth-largest city after Kyiv, Kharkiv and Odesa.

Immediately after its foundation, Dnipro, or as it was then known Yekaterinoslav, began to develop exclusively on the right bank of the Dnieper River. At first the city developed radially from the central point provided by the Transfiguration Cathedral. Neoclassical structures of brick and stone construction were preferred and the city began to take on the appearance of a typical European city of the era. Of these buildings many have been retained in the city's older Sobornyi District.[78] Amongst the most important buildings of this era are the Transfiguration Cathedral, and a number of buildings in the area surrounding Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, including the Khrennikov House.

Over the next few decades, until the October Revolution in 1917 the city did not change much in appearance and the predominant architectural style remained that of neo-classicism. Notable buildings built in the era preceding the Bolsheviks' rise to power and the establishment of communist Ukraine and later its absorption into the Soviet Union, include the main building of the Dnipro Polytechnic, which was built in 1899–1901,[81] the art-nouveau inspired building of the city's former Duma,[82] the Dnipropetrovsk National Historical Museum, and the Mechnikov Regional Hospital. Other buildings of the era that did not fit the typical architectural style of the time in Dnipropetrovsk include,[83] the Ukrainian-influenced Grand Hotel Ukraine, the Russian revivalist style railway station (since reconstructed),[84] and the art-nouveau Astoriya building on Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt.

Stalinist architecture (monumental soviet classicism) dominates in the city centre.[86] Once the bolsheviks had taken power in Dnipropetrovsk the city was gradually purged of tsarist-era monuments and monumental architecture was stripped of Imperial coats of arms and other non-socialist symbolism. In 1917, a monument to Catherine the Great that stood in front of the Mining Institute was replaced with one of Russian academic Mikhail Lomonosov.[87] Later, due to damage from the Second World War, a number of large buildings were reconstructed. The main railway station, for example, was stripped of its Russian-revival ornamentation and redesigned in the style of Stalinist social-realism,[88] whilst the Grand Hotel Ukraine survived the war but was later simplified much in design, with its roof being reconstructed in a typical French mansard style as opposed to the ornamental Ukrainian baroque of the pre-war era. Other badly damaged buildings were, more often than not, demolished completely and replaced with new structures.[89] This is one of the main reasons why much of Dnipro's central avenue, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, is designed in the style of Stalinist Social Realism.[90] Many pre-revolution buildings were also reconstructed to suit new purposes. For example, the Emperor Nicholas II Commercial Institute in the city was reconstructed to serve as the administrative centre for the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, a function it fulfils to this day. Other buildings, such as the Potemkin Palace were given over to the proletariat, in this case as the students' union of the Oles Honchar Dnipro National University.

After the death of Stalin and appointment of Khrushchev, who had spent his early working years in Ukraine, as party secretary, the industrialisation of Dnipropetrovsk became even more profound, with the Southern (Yuzhne) Missile and Rocket factory being set up in the city. However, this was not the only development and many other factories, especially metallurgical and heavy-manufacturing plants, were set up in the city.[91] At this point Dnipropetrovsk became one of the most important manufacturing cities in the Soviet Union, producing many goods from small articles like screws and vacuum cleaners to aircraft engine pieces and ballistic missiles. As a result of all this industrialisation the city's inner suburbs became increasingly polluted and were gradually given over to large, unsightly industrial enterprises. At the same time the extensive development of the city's left bank and western suburbs as new residential areas began.[91] The low-rise tenant houses of the Khrushchev era (Khrushchyovkas) gave way to the construction of high-rise prefabricated apartment blocks (similar to German Plattenbaus). In 1976 in line with the city's 1926 renaming a large monumental statue of Grigoriy Petrovsky was placed on the square in front of the city's station.[92] This statue was destroyed by an angry mob early 2016.[93]

To this day the city is characterised by its mix of architectural styles, with much of the city's centre consisting of pre-revolutionary buildings in a variety of styles, stalinist buildings and constructivist architecture, whilst residential districts are, more often than not, made up of aesthetically simple, technically outdated mid-rise and high-rise housing stock from the Soviet era. Despite this, the city does have a large number of 'private sectors' were the tradition of building and maintaining individual detached housing has continued to this day.

Since the independence of Ukraine in 1991 and the economic development that followed, a number of large commercial and business centres have been built in the city's outskirts.

Late November 2015 about 300 streets, 5 of the 8 city districts and one metro station were renamed to comply with decommunization laws.[71]

Demographics

|

|

The population of the city is about 1 million people. In 2011, the average age of the city's resident population was 40 years. The number of males declined slightly more than the number of females. The natural population growth in Dnipro is slightly higher than growth in Ukraine in general.

Between 1923 and 1933 the Ukrainian proportion of the population of Dnipropetrovsk increased from 16% to 48%. This was part of a national trend.[106]

| Year | Ethnicity of Citizens | Foreign Citizens |

Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russian | Ukrainian | Jewish | Polish | German | |||

| 1887 | 47,200 | 17,787 | 39,979 | 3,418 | 1,438 | 1,075 | [97] |

| 1887 | 42.6% | 16.0% | 36.1% | 3.1% | 1.3% | 1.0% | [97] |

| 1904(?) | 52% | 40% | 4.5% | Not Stated | Not Stated | [101] | |

| Ethnic group | 1926[107] | 1939[108] | 1959[109] | 1989[110] | 2001[110] | 2017[111] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ukrainians | 36.0% | 54.6% | 61.5% | 62.5% | 72.6% | 82% |

| Russians | 31.6% | 23.4% | 27.9% | 31.0% | 23.5% | 13% |

| Jews | 26.8% | 17.9% | 7.6% | 3.2% | 1.0% | |

| Belarusians | 1.9% | 1.9% | 1.7% | 1.0% |

In a survey in June–July 2017, 63% of residents said that they spoke Russian at home, 9% spoke Ukrainian, and 25% spoke Ukrainian and Russian equally.[111]

The same survey reported the following results for the religion of adult residents.[111]

- 49% Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyivan Patriarchate

- 6% Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate

- 7% atheist

- 1% belong to other religions

- 28% believe in God, but do not belong to any religion

- 5% found it difficult to answer

Economy

.jpg)

Dnipro is a major industrial centre of Ukraine. It has several facilities devoted to heavy industry that produce a wide range of products, including cast-iron, launch vehicles, rolled metal, pipes, machinery, different mining combines, agricultural equipment, tractors, trolleybuses, refrigerators, different chemicals and many others. The most famous and the oldest (founded in the 19th century) is the Metallurgical Plant named after Petrovsky. The city also has big food processing and light industry factories. Many sewing and dress-making factories work for France, Canada, Germany and Great Britain , using the most advanced technologies, materials and design. Dnipro has also dominated in the aerospace industry since the 1950s; construction department Yuzhnoye Design Bureau and Yuzhmash are well known to the specialists all over the world. In 2018 a private Texas-based aerospace firm Firefly Aerospace opened a Research and Development (R&D) center in Dnipro to develop small and medium-sized launch vehicles for commercial launches to orbit.[112]

Metals and metallurgy is the city's core industry in terms of output. Employment in the city is concentrated in large-sized enterprises. Metallurgical enterprises are based in the city and account for over 47% of its industrial output. These enterprises are important contributors to the city's budget and, with 80% of their output being exported, to Ukraine's foreign exchange reserve. Dnipro serves as the main import hub for foreign goods coming into the oblast and, on average, accounted for 58% of the oblast's imports between 2005 and 2011. With economic conditions improving even further in 2010 and 2011, registered unemployment fell to about 4,100 by the end of 2011.

Dniproavia, an airline, has its head office on the grounds of Dnipropetrovsk International Airport.[113] The main shareholder in the airline is Ukrainian-Israeli entrepreneur Ihor Kolomoyskyi's Privat Group, a global business group, based in the city and grouped around the Privatbank. Privat Group controls thousands of companies of virtually every industry in Ukraine, European Union, Georgia, Ghana, Russia, Romania, United States and other countries. Steel, oil & gas, chemical and energy are sectors of the group's prime influence and expertise. None of the group's capital is publicly traded on the stock exchange. Group's founding owners are natives of Dnipro and made their entire career here. Privatbank, the core of the group, is the largest commercial bank in Ukraine. In March 2014 was named by the American review magazine Global Finance as "the Best Bank in Ukraine for 2014" while British magazine The Banker in November 2013 named again the same bank as "the Bank of the year 2013 in Ukraine".

Privat Group is in business conflict with the Interpipe, also based in Dnipro area. The influential metallurgical mill company founded and mostly owned by the local business oligarch Viktor Pinchuk. Other company headquartered in Dnipro is ATB-Market. The company owns the largest national network of retail shops. The City of Dnipro's economy is dominated by the wholesale and retail trade sector, which accounted for 53% of the output of non-financial enterprises in 2010.

| Year | Factories & Plants |

Employees | Production Volume[114] | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rubles | 2007 £ million |

2007 USD million | ||||

| 1880 | 49 | 572 | 1,500,000 | £10.5 m | $21 m | [97] |

| 1903 | 194 | 10,649 | 21,500,000 | £177.5 m | $355 m | [97] |

| Year | Enterprises | Earnings[114][115] | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rubles | 2007 £ million |

2007 USD million | |||

| 1900 | 1,800 | 40,000,000 | £328.7 m | $658 m | [101] |

| 1940 | 622 | 1,096,929,000 | £2,120.3 m | $4,242 m | [97] |

Transport

Local transportation

The main forms of public transport used in Dnipro are trams, buses, electric trolley buses and marshrutkas—private minibuses. In addition to this there are a large number of taxi firms operating in the city, and many residents have private cars.

The city's municipal roads also suffer from the same funding problems as the trams, with many of them in a very poor technical state. It is not uncommon to find very large potholes and crumbling surfaces on many of Dnipro's smaller roads. Major roads and highways are of better quality. In recent years the situation has, however, been improving, with a number of new used trams bought from the German cities of Dresden and Magdeburg,[116] and a number of roads, including Schmidt Street and Moskovsky Street being reconstructed with modern road-building techniques.[117]

Dnipro also has a metro system, opened in 1995, which consists of one line and 6 stations.[118] The 1980 official plans for four different lines were never made reality.[119] In 2011 the metro was transferred to municipal ownership in the hope that this will help it secure a loan from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.[120] In 2011, plans envisioned an expansion of three station, Teatralna, Tsentralna and Muzeina, to be completed by 2015.[121] The opening of these three stations have been repeatedly delayed and they will not open until 2023 at the earliest.[122][123]

Suburban transportation

Dnipro has some highways crossing through the city. The most popular routes are from Kiyv, Donetsk, Kharkiv and Zaporizhia. Transit through the city is also available. As of 2011 the city is also seeing construction of a southern urban bypass, which will allow automobile traffic to proceed around the city centre. This is expected to both improve air quality and reduce transport issues from heavy freight lorries that pass through the city centre.

The largest bus station in eastern Ukraine is located in Dnipro, from where bus routes are available to all over the country, including some international routes to Russia, Poland, Germany, Moldova and Turkey. It is located near the city's central railway station.

In the summertime, there are some routes available by hydrofoils on the Dnieper River, whilst various tourist ships on their way down the river, (Kiev–Kherson–Odessa) tend to make a stop in the city. Dnipro's river port is located close to the area surrounding the central railway station, on the banks of the river. It is a good example of constructivist architecture from the late period of the Soviet Union.

Rail

The city is a large railway junction, with many daily trains running to and from Eastern Europe and on domestic routes within Ukraine.

There are two railway terminals, Dnipro Holovnyi (main station) and Dnipro Lotsmanska (south station).

Two express passenger services run each day between Kiev and Dnipro under the name 'Capital Express'. Other daytime services include suburban trains to towns and villages in the surrounding Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. Most long-distance trains tend to run at night to reduce the amount of daytime hours spent travelling by each passenger.

Domestic connections exist between Dnipro and Kiev, Lviv, Simferopol, Odessa, Ivano-Frankivsk, Truskavets, Donetsk, Kharkiv and many other smaller Ukrainian cities, whilst international destinations include, amongst others, Minsk in Belarus, Moscow's Kursky Station and Saint Petersburg's Vitebsky Station in Russia, Baku—the capital of Azerbaijan, and the Bulgarian seaside resort of Varna.

Aviation

The city is served by Dnipropetrovsk International Airport (IATA: DNK) and is connected to European and Middle Eastern cities with daily flights. It is located 15 km (9.3 mi) southeast from the city center.

Water transportation

The city has a river port located on the left bank of the Dnieper. There is also a railroad freight station.

Education

There are 163 educational institutions among them schools, gymnasiums and boarding schools. For children of pre-school age there are 174 institutions, also a lot of out-of -school institutions such as center of out-of-school work. Eighty-seven institutions that are recognized on all Ukrainian and regional levels.

In a survey in June–July 2017, adult respondents reported the following educational levels:[111]

- 1% primary or incomplete secondary education

- 13% general secondary education

- 46% vocational secondary education

- 39% university education (including incomplete university education)

In 2006 Dnipropetrovsk hosted the All-Ukrainian Olympiad in Information Technology; in 2008, that for Mathematics, and in 2009 the semi-final of the All-Ukrainian Olympiad in Programming for the Eastern Region. In the same year as the latter took place, the youth group 'Eksperiment', an organisation promoting increased cultural awareness amongst Ukrainians, was founded in the city.

Higher education

Dnipro is a major educational centre in Ukraine and is home to two of Ukraine's top-ten universities; the Oles Honchar Dnipro National University and Dnipro Polytechnic National Technical University. The system of high education institutions connects 38 institutions in Dnipro, among them 14 of IV and ІІІ levels of accreditation, and 22 of І and ІІ levels of accreditation. In year 2012 National Mining Institute was on the 7th and National University named after O. Honchar was on the 9th place among the best high education institutions in "TOP-200 Ukraine" list.

The list below is a list of all current state-organised higher educational institutions (not included are non-independent subdivisions of other universities not based in Dnipro).

|

|

Currently around 55,000 students study in Dnipro, a significant number of whom are students from abroad.

Culture

Attractions

The city has a variety of theatres (plus an Opera) and museums of interest to tourists, including the Dmytro Yavornytsky National Historical Museum. There are also several parks, restaurants and beaches.

The major streets of the city were renamed in honour of Marxist heroes during the Soviet era. Following the 2015 law on decommunization these have been renamed.[15][71]

The central thoroughfare is known as Akademik Yavornytskyi Prospekt, a, wide and long boulevard that stretches east to west through the centre of the city. It was founded in the 18th century and parts of its buildings are the actual decoration of the city. In the heart of the city is Soborna Square, which includes the majestic cathedral founded by order of Catherine the Great in 1787.

On the square, there are some remarkable buildings: the Museum of History, Diorama "Battle for the Dnieper River (World War II)", and also the park in which one can rest in the hot summer. Walking down the hill to the Dnieper River, one arrives in the large Taras Shevchenko Park (which is on the right bank of the river) and on Monastyrsky Island. This island is one of the most interesting places in the city. In the 9th century, the Byzantine monks based a monastery here.

A few areas retain their historical character: all of Central Avenue, some street-blocks on the main hill (the Nagorna part) between Pushkin Prospekt and Embankment, and sections near Globa (formerly known as Chkalov park until it was recently renamed) and Shevchenko parks have been untouched for 150 years.

The Dnieper River keeps the climate mild. It is visible from many points in Dnipro. From any of the three hills in the city, one can see a view of the river, islands, parks, outskirts, river banks and other hills.

There was no need to build skyscrapers in the city in Soviet times. The major industries preferred to locate their offices close to their factories and away from the centre of town. Most new office buildings are built in the same architectural style as the old buildings. A number, however, display more modern aesthetics, and some blend the two styles.

Sports

FC Dnipro football club, used to play in the Ukrainian Premier League and UEFA Europa League, and were the only Soviet team to win the USSR Federation Cup twice. The club was owned by the Privat Group. Note: A bandy team, a basketball team and others use the same name.

Other local football include: FC Lokomotyv Dnipropetrovsk and FC Spartak Dnipropetrovsk, both of which have large fan bases. SC Dnipro-1 is another team emerged in 2017.

Recently the city built a new soccer stadium; the Dnipro-Arena has a capacity of 31,003 people and was built as a replacement for Dnipro's old stadium, Stadium Meteor. The Dnipro-Arena hosted the 2010 FIFA World Cup qualification game between Ukraine and England on 10 October 2009. The Dnipro Arena was initially chosen as one of the Ukrainian venues for their joint Euro 2012 bid with Poland. However, it was dropped from the list in May 2009 as the capacity fell short of the minimum 33,000 seats required by UEFA.[124][125]

The city is the centre of Ukrainian bandy. The Ukrainian Federation of Bandy and Rink-Bandy has its office in the city.[126] The foremost local bandy club is Dnipro Dnipropetrovsk, which won the Ukrainian championship in 2014.

Notable people from Dnipro

- Oksana Baiul – figure skating Olympic gold medalist, 1994

- Helena Blavatsky – founder of Theosophical Society

- Henadiy Boholyubov – billionaire businessman, Privat Group

- Marina Maximillian Blumin – singer-songwriter and Kokhav Nolad contestant

- Gennadiy Bogolyubov (born 1961/1962), Dipro-born Ukrainian-Israeli billionaire businessman.

- Artem Dolgopyat (born 1997), Ukrainian-born Israeli artistic gymnast.

- Marharyta Dorozhon – Ukrainian/Israeli Olympic javelin thrower

- Viktor Chebrikov – head of the KGB from December 1982 to October 1988.

- Artem Dolgopyat (born 1997), Israeli artistic gymnast (second in world championships)

- Katherine Esau – botanist

- Kyrylo Fesenko – NBA basketball player

- Vsevolod Garshin – Russian writer

- Helen Gerardia – painter[127]

- Linor Goralik – writer

- Ilya Kabakov – contemporary artist

- Leonid Kogan – violinist

- Yuri Krasny — educational theorist

- Victor Kravchenko – Soviet dissident

- Inessa Kravets – long jumper and triple jumper (holds women's record in triple jump)

- Leonid Kuchma – President of Ukraine in 1994–2005

- Pavlo Lazarenko – Prime Minister of Ukraine in 1996–97

- Leonid Levin – computer scientist

- Konstantin Lopushansky – film director

- Yuriy Meshkov – President of Crimea in 1994–1995

- Igor Morozov (singer) – Russian-Ukrainian opera singer, soloist of Moscow's Bolshoi-Theatre, "People's Artist of Russia"

- David Nachmansohn – biochemist

- Mikhail Nekrich – musician

- Igor Olshansky – NFL defensive tackle

- Viktor Petrov – historian and writer also known under his pen names Domontovych and Ber

- Gregor Piatigorsky – cellist

- Viktor Pinchuk – business oligarch

- Olesya Povh – Olympic bronze medalist runner

- Oleh Protasov – former Ukrainian footballer

- Sergei Prokofiev – composer

- Inna Ryzhykh – professional triathlete

- Boris Sagal – American television and film director, born there.

- Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson – "Lubavitcher Rebbe" headed the Worldwide Chabad-Lubavitch Movement, posthumously awarded the U.S. Congressional Gold Medal

- Moses Schönfinkel – logician and mathematician

- Adel Tankova (born 2000) – Ukrainian-born Israeli Olympic figure skater

- Oleg Tsaryov – deputy of the Verkhovna Rada in 2002–2014, politician and separatist leader of Novorossiya in 2014

- Oleg Tverdokhleb – athlete, 400-metre hurdles

- Yulia Tymoshenko – Prime Minister of Ukraine in 2005 and 2007–10, and candidate in the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election

- Tatiana Volosozhar – figure skating Olympic gold medalist, 2014

- Anna Goloktionova - Humanitarian Mental Health Coordinator

See also List of mayors and political chiefs of the Dnipro city administration.

Twin towns – sister cities

Dnipro is twinned with:[128][129]

See also

- Dnepropetrovsk maniacs

- Golden Rose Synagogue, Dnipro

Notes

- A closed city did not allow foreigners inside without official permission.

- On 29 December 2015 the city council officially changed the reference of the city naming from referring to Petrovsky to being in honor of Saint Peter,[17] thus making the name consistent with the law without actually changing the name itself. On 3 February 2016 a draft law was registered in the Verkhovna Rada (the Ukrainian parliament) to change the name of the city to Dnipro.[18] On 19 May 2016 the Ukrainian parliament passed a bill to officially rename the city (to Dnipro). The resolution was approved by 247 out of the 344 MPs, with 16 opposing the measure.[10] The city's mayor Borys Filatov described the renaming of the city as "controversial and irrelevant".[19] Oleksandr Vilkul (who stood against Filatov at the last election for mayor) claimed that 90% of residents were opposed to the change in the city's name.[19]

- On 1 June 2016 the Ukrainian parliament refused to support a resolution to cancel the renaming.[20] On 16 June 2016, 48 MPs appealed against the renaming in the Constitutional Court of Ukraine.[21] The Constitutional Court refused to consider this case on 12 October 2016.[20]

- There is some confusion concerning the date of this map. According to the image file the map is by Schubert and dates from about 1860, but Ukrainian Wikipedia claims that it dates from 1885. The map shows the old Amur railway bridge across the river, which was completed in 1884.

References

- Oleh Repan. The origins of Dnipro, the city and its name. The Ukrainian Week. July 2017 (page 46)

- Borys Filatov becomes Dnipropetrovsk mayor – election commission, Ukrinform (18 November 2015)

- Чисельність населення на 1 липня 2011 року, та середня за січень–червень 2011 року [Population as of 1 July 2011, and the average for January – June 2011]. Department of Statistics in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 20 October 2013.

- Общие сведения и статистика [General information and statistics]. gorod.dp.ua (in Russian). Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- Ukrcensus.gov.ua — City Archived 9 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed on 8 March 2007

- "Official statistics, 01.08.2012 (Ukrainian)". Dneprstat.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "Coordinates + Total Distance". MapCrow. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- "Чисельність наявного населення України (Actual population of Ukraine)" (PDF) (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Charles Wynn. Workers, Strikes, and Pogroms: The Donbass-Dnepr Bend in Late Imperial Russia, 1870–1905 - "[The Empress] and her favorite, Prince Grigorii Potemkin, the city's first governor-general and the de facto viceroy of southern Russia, had big plans for Ekaterinoslav. Potemkin envisioned Ekaterinoslav as the 'Athens of southern Russia' and as Russia's third capital - 'the centre of the administrative, economic, and cultural life of southern Russia.'"

- "Dnipropetrovsk renamed Dnipro". UNIAN. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

The decision comes into force from the date of its adoption.

(in Ukrainian) Верховна Рада України (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine), Поіменне голосування про проект Постанови про перейменування міста Дніпропетровська Дніпропетровської області (№3864) (Roll-call vote on the draft resolution on renaming of Dnipropetrovsk Dnipropetrovsk region №3864), 19 May 2016. - Проект Закону про внесення змін до статті 133 Конституції України (щодо перейменування Дніпропетровської області) [Draft Law on Amendments to Article 133 of the Constitution of Ukraine (regarding the renaming of the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast)], Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, 27 April 2018, Number 8329 of the 8th session of the VIII convocation, retrieved 28 April 2018 Пояснювальна записка 27.04.2018 [Explanatory Note 27 April 2018]

- "English map of 1820" (JPG). Arhivtime.ru. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Zhuk, S (2010). Rock and Roll in the Rocket City: The West, Identity, and Ideology in Soviet Dniepropetrovsk, 1960–1985. Woodrow Wilson Center Press with Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801895500.

- Rada approves historic bills to part with Soviet legacy, The Ukrainian Weekly (17 April 2015)

- Poroshenko signed the laws about decomunization. Ukrayinska Pravda. 15 May 2015

Poroshenko signs laws on denouncing Communist, Nazi regimes, Interfax-Ukraine. 15 May 20

Goodbye, Lenin: Ukraine moves to ban communist symbols, BBC News (14 April 2015) - Ukraine tears down controversial statue, by Rostyslav Khotin, BBC News (27 November 2009)

Same article on UNIAN. - LB.ua, Днепропетровск собираются "переименовать" в честь Святого Петра (Dnepropetrovsk to be "renamed" in honour of St. Peter), 29 December 2015.

- (in Ukrainian) In Rada registered a bill to rename Dnipropetrovsk, Ukrayinska Pravda (3 February 2016)

- Kyiv Post, Verkhovna Rada renames Dnipropetrovsk as Dnipro, 19 May 2016.

- (in Ukrainian) Constitutional Court refused to consider renaming Dnipropetrovsk, Ukrayinska Pravda (12 October 2016)

- MPs appeal against Dnipropetrovsk renaming at Constitutional Court, Interfax-Ukraine (6 June 2016)

- Mikhail Levchenko. Hanshchyna (Ганьщина Україна). Opyt russko-ukrainskago slovari︠a︡. Tip. Gubernskago upravlenii︠a︡, 1874

- "Welcome to Dnipropetrovsk! " City Guide – Dnipropetrovsk". Gorod.dp.ua. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Go2Kiev Dnepropetrovsk". Go2kiev.com. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Plokhy, Serhii, The Cossacks and Religion in Early Modern Ukraine, pub Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-19-924739-0, pages 26, 37, 40, 51, 60–1, 142, 245, and 268.

- Guillaume le Vasseur de Beauplan wrote a book Description d'Ukrainie, published in 1651 and 1660.

- www.day.kiev.ua Above Kodak, this year the unique fortress marks its 375th anniversary, by Mykola Chaban, 2010.

- "www.eugene.com.ua Dnepropetrovsk History". Eugene.com.ua. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Днепропетровск празднует именины. Память великомученицы Екатерины [Dnepropetrovsk celebrates its nameday. In the memory of Catherine the Great Martyr]. mir-pravoslaviya.org.ua (in Russian). 25 December 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- Святая великомученица Екатерина Александрийская [The Holy Great Martyr Catherine of Alexandria] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- Establishment and development of the Dnipropetrovsk city (Виникнення і розвиток міста Дніпропетровськ). The History of Cities and Villages of the Ukrainian SSR.

- S. S. Montefiore: Prince of Princes – The Life of Potemkin

- Kavun, Maksim. Загадки Преображенского собора [Riddles surrounding the Transfiguration Cathedral] (in Russian). Gorod.dp.ua. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "Ukrainetrek Dnepropetrovsk (City)". Ukrainetrek.com. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Surh, Gerald (27 October 2003). "Ekaterinoslav City in 1905: Workers, Jews, and Violence]". International Labor and Working-Class History. 64: 139–166. doi:10.1017/S0147547903000231.

- "Grand Hotel Ukraine, Hotel's History". Grand-hotel-ukraine.dp.ua. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- War Without Fronts: Atamans and Commissars in Ukraine, 1917–1919 by Mikhail Akulov, Harvard University, August 2013 (page 102)

- Borderlands into Bordered Lands: Geopolitics of Identity in Post-Soviet Ukraine (Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society, Vol. 98) (Volume 98), Ibidem Verlag, 2010, ISBN 383820042X (page 24)

- The Kravchenko Case: One Man's War Against Stalin by Gary Kern, Enigma Books, 2007, ISBN 978-1-929631-73-5, page 191

- "1941". MusicAndHistory. Archived from the original on 28 August 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- "Onwar.com, Red Army crosses Dniepr River". Onwar.com. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Hilberg 1985, p. 372.

- New York Times, 20 June 1990 Evolution in Europe; Soviet Troops Kill an Inmate During Riot in Ukrainian Jail This stated that TASS had issued a statement saying that there had been a riot by 2,000 inmates in a prison in Dnipropetrovsk. The riot broke out on Thursday 14 June 1990, and was quelled by Soviet troops on Friday 15 June 1990, killing one prisoner and wounding another.

- "Kievskie vedomosti, 14 August 2000". Khpg.org. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "Case 92: Dnepropetrovsk Maniacs – Casefile: True Crime Podcast". Casefile: True Crime Podcast. 11 August 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- "Dnepropetrovsk Maniacs: Court delivers its verdicts" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 12 February 2012.

- "Ukraine protests spread to Yanukovich heartland". Financial Times. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "В Днепропетровске больше трех тысяч человек собрались возле ОГА – Днепропетровск". Dp.vgorode.ua. 26 January 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- Ukraine protests 'spread' into Russia-influenced east, BBC News (26 January 2014)

- "EuroMaidan rallies in Ukraine (Jan. 24–27 live updates)". Kyiv Post. 26 January 2014.

- "Восток и Юг Украины вышел пикетировать ОГА: в Запорожье стреляют в митингующих, а в Сумах просят подмоги (обновлено 2.34)". Delo UA. 27 January 2014.

- "Майдан в Днепропетровске: стычки с титушками и ультиматум губернатору". Delo.ua. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- "Беспорядки в Днепропетровске, ранены четыре человека, семь задержаны – Днепропетровск". Dp.vgorode.ua. 26 January 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- "Видео как "Титушки" избивают людей возле "Днепр-Арены" – Днепропетровск". Dp.vgorode.ua. 27 January 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- "Днепропетровск: титушки и милиция против местного Майдана". News.liga.net. 26 January 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- "Колесников не увидел "титушек" возле здания Днепропетровской ОГА – Днепропетровск.comments.ua". Dnepr.comments.ua. 26 January 2014. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- "Регионы онлайн: "Крымское Межигорье" показали людям – Новости Украины сегодня, последние новостиУкраины – bigmir)net – Новости дня – bigmir)net". News.bigmir.net. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- "Днепропетровскую ОГА обнесли колючей проволокой и смазали солидолом – Днепропетровск". Dp.vgorode.ua. 28 January 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- "Бывший СССР: Украина: Государство временно недоступно". Lenta.ru. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- "Disturbances escalate in western Ukraine". euronews.com. 20 February 2014. Archived from the original on 12 June 2015.

- (in Ukrainian) Residents Dnipropetrovsk forced mayor to withdraw from the Party of Regions Archived 7 September 2014 at Archive.today, Espreso TV (February 22, 2014)

(in Russian) Dnipropetrovsk mayor left the PR 'for peace in the city' Archived 5 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, NEWSru.ua (February 22, 2014)

(in Ukrainian) In Dnepropetrovsk Lenin Square was renamed Heroes Square, the Mayor released from PR, Ukrayinska Pravda (February 22, 2014) - Ukraine crisis timeline, BBC News

- В Днепропетровске состоялись два митинга: за и против новой власти [Two meetings took place in Dnepropetrovsk: for and against the new government] (in Russian). ukrinform.ua. 1 March 2014. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014.

- Olga Rudenko, Special for USA TODAY (14 March 2014). "In East Ukraine, fear of Putin, anger at Kiev". Usatoday.com. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "Ukraine: the Day After". Weeklystandard.com. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "Пам'ятник Леніну у Дніпропетровську остаточно перетворили в купу каміння "Monument to Lenin in Dnipropetrovsk finally turned into a pile of stones"". ТСН.ua. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "Lenin Statue Toppled in Ukrainian City of Dnipropetrovsk". Yahoo News Singapore. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- (in Ukrainian) "Another monument to Lenin was dismantled in Dnipropetrovsk". Ukrayinska Pravda. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Democracy and Disorientation: Ukraine Votes in Local Elections by Balázs Jarábik, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (23 October 2015 )

- Borys Filatov becomes Dnipropetrovsk mayor – election commission, Ukrinform (18 November 2015)

- (in Ukrainian) Street signs were Dnipropetrovsk nedekomunizovanymy, Radio Svoboda (2 December 2015)

- Peel, M. C.; Finlayson B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen−Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Rivas-Martínez, Salvador (2004). "Bioclimatic & Biogeographic Maps of Europe". University of León. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- See also: klimadiagramme.de – Climate in Dnipropetrovsk URL accessed on 20 March 2007

- "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine – Population". Mfa.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- www.mongabay.com Russia – Geography states: "Since 1990 Russian experts have added to the list the following less spectacular but equally threatening environmental crises: the Dnepropetrovsk-Donets and Kuznets coal-mining and metallurgical centres, which have severely polluted air and water and vast areas of decimated landscape;..."

- "Климат Днепра (Climate of Dnipro)" (in Russian). Pogoda.ru.net. 2016. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- "История Днепропетровска и Приднепровья". Gorod.dp.ua. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "История Днепропетровска и Приднепровья". Gorod.dp.ua. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- In East Ukraine, fear of Putin, anger at Kiev

Ukraine: the Day After

Пам'ятник Леніну у Дніпропетровську остаточно перетворили в купу каміння "Monument to Lenin in Dnipropetrovsk finally turned into a pile of stones" - Вт, 12 марта 201307:51. "Национальный Горный Университет – Днепропетровск". Gorod.dp.ua. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Городская Дума – Старый Днепропетровск – Ретрофото – Фотоальбомы – Памятники, архитектура, история, туризм". Dneprotur.ucoz.com. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "История Днепропетровска и Приднепровья". Gorod.dp.ua. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Железнодорожный вокзал, Днепропетровск, Украина [Railway station, Dnepropetrovsk, Ukraine] (in Russian). ef2012.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012.

- "Торговый комплекс "Пассаж"". Akselrod-estate.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "От "сталинского ампира" до "брежневского минимализма" " www.DNEPR.com – Главный портал города Днепропетровска". DNEPR.com. 7 October 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Вт, 12 марта 201307:51 (14 September 2011). "Ломоносову М.В., памятник – Днепропетровск". Gorod.dp.ua. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Центральный железнодорожный вокзал был уничтожен во время войны. Потребовалось строительство нового здания

- "История Днепропетровска и Приднепровья". Gorod.dp.ua. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Центральный проспект почти полностью был разрушен. Практически его нужно было создать заново

- "История Днепропетровска и Приднепровья". Gorod.dp.ua. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- В 1976 г. архитектурно-художественная композиция привокзальной площади была завершена постановкой памятника Г. И. Петровскому

- Soviet-Era. "Monument Torn Down in Eastern Ukraine". www.rferl.org.

- Eugene.com states that the population in the early 19th century was 6,389, whilst Cheba states that this was the population in 1800.

- Kardasis, Vassilis, Diaspora Merchants in the Black Sea: The Greeks in Southern Russia, 1775–1861, pub Lexington Books, 2001, ISBN 0-7391-0245-1, page 34.

- ""History" a Dnipropetrovsk Travel Page by Cheba". VirtualTourist.com. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Dnepropetrovsk Jewish Community (DJC.com) – About Yekaterinoslav Dnepropetrovsk, accessed 1 February 2014. (English language version of this page has disappeared since 2008, but Russian language version still present.)

- Cheba states that in a census for 1 January 1866 the population was 22,846. Eugene.com states 22,816 for 1865, while DJC.com states 22,846 for 1865.

- Eugene.com states that the population in 1887 was 48,000, whilst Gerald Surh states that it was 47,000. Polish wikipedia says 48100.

Dnepropetrovsk History. www.eugene.com.ua

Surh, Gerald, Ekaterinoslav City in 1905: Workers, Jews, and Violence - Eugene.com states that the population in 1897 was 121,200, Cheba says 121,216, and Surh says 112,800, whilst Vassilis Kardasis states that it was 113,000.

Dnepropetrovsk History. www.eugene.com.ua

"History" a Dnipropetrovsk Travel Page by Cheba

Gerald Surh, Ekaterinoslav City in 1905: Workers, Jews, and Violence

Kardasis, Vassilis, Diaspora Merchants in the Black Sea: The Greeks in Southern Russia, 1775–1861 - "Surh, Gerald, Ekaterinoslav City in 1905: Workers, Jews, and Violence, published in International Labor and Working-Class History No. 64, Fall 2003, pages 139–166". Journals.cambridge.org. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- The emergency evacuation of cities: a cross-national historical and geographical study, by Wilbur Zelinsky, Leszek A. Kosiński, pub Rowman & Littlefield, 1991, ISBN 978-0-8476-7673-6.

- "China in Figures" says 1,178,000.

- "Dnipropetrovsk." The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2008. Encyclopedia.com.

- United Nations Statistics Division: cities, population, census years (discontinued), code 14720 give the population for the city proper as 1,147,000 for 1996, and 1,122,400 for 1998.

Eugene.com states that the population in 1998 was 1,137,000 - Volodymyr Kubiyovych; Zenon Kuzelia, Енциклопедія українознавства (Encyclopedia of Ukrainian studies), 3-volumes, Kiev, 1994, ISBN 5-7702-0554-7

- Всесоюзная перепись населения 1926 года. М.: Издание ЦСУ Союза ССР, 1928–29

- Всесоюзная перепись населения 1939 года. Национальный состав населения районов, городов и крупных сел союзных республик СССР. г. Днепропетровск [All-Union census of 1939. The national composition of the population of the districts, cities and large villages of the Union Republics of the USSR. City of Dnepropetrovsk] (in Russian). demoscope.ru. Retrieved 27 July 2019.