DVD

DVD (abbreviation for Digital Versatile Disc or Digital Video Disc)[8][9] is a digital optical disc storage format invented and developed in 1995 and released in late 1996. The medium can store any kind of digital data and is widely used for software and other computer files as well as video programs watched using DVD players. DVDs offer higher storage capacity than compact discs while having the same dimensions.

| |

The data side of a DVD manufactured by Sony DADC | |

| Media type | Optical disc |

|---|---|

| Encoding | DVD-ROM and DVD-R(W) use one encoding, DVD-RAM and DVD+R(W) uses another |

| Capacity | 4.7 GB (single-sided, single-layer – common) 8.5 GB (single-sided, double-layer) 9.4 GB (double-sided, single-layer) 17.08 GB (double-sided, double-layer) Up to four layers are possible in a standard form DVD. |

| Read mechanism | 300-650 nm laser, 10.5 Mbit/s (1×) |

| Write mechanism | 650 nm laser with a focused beam using more power than for reading, 10.5 Mbit/s (1×) |

| Standard | DVD Forum's DVD Books[1][2][3] and DVD+RW Alliance specifications |

| Developed by | Sony, Panasonic, Toshiba, Philips, Samsung |

| Dimensions | Diameter: 12 cm (4.7 in) Thickness: 1.2 mm (0.047 in) |

| Weight | 16 grams (0.56 oz) |

| Usage | Standard definition video, standard definition sound, PS2, Xbox and Xbox 360 games |

| Extended from | LaserDisc Compact disc |

| Extended to | DVD+RW, DVD-RAM (Fixed-track writable media) HD-DVD Blu-ray |

| Released | November 1, 1996 (Japan)[4] January 1997 (CIS and other Asia) March 24, 1997 (United States)[5][6][7] March 1998 (Europe) February 1999 (Australia) |

Prerecorded DVDs are mass-produced using molding machines that physically stamp data onto the DVD. Such discs are a form of DVD-ROM because data can only be read and not written or erased. Blank recordable DVD discs (DVD-R and DVD+R) can be recorded once using a DVD recorder and then function as a DVD-ROM. Rewritable DVDs (DVD-RW, DVD+RW, and DVD-RAM) can be recorded and erased many times.

DVDs are used in DVD-Video consumer digital video format and in DVD-Audio consumer digital audio format as well as for authoring DVD discs written in a special AVCHD format to hold high definition material (often in conjunction with AVCHD format camcorders). DVDs containing other types of information may be referred to as DVD data discs.

Etymology

The Oxford English Dictionary comments that, "In 1995, rival manufacturers of the product initially named digital video disc agreed that, in order to emphasize the flexibility of the format for multimedia applications, the preferred abbreviation DVD would be understood to denote digital versatile disc." The OED also states that in 1995, "The companies said the official name of the format will simply be DVD. Toshiba had been using the name 'digital video disc', but that was switched to 'digital versatile disc' after computer companies complained that it left out their applications."[10]

"Digital versatile disc" is the explanation provided in a DVD Forum Primer from 2000[11] and in the DVD Forum's mission statement.[12]

History

Development

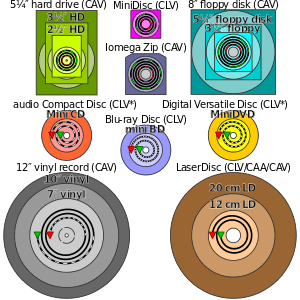

* Some CD-R(W) and DVD-R(W)/DVD+R(W) recorders operate in ZCLV, CAA or CAV modes, but most work in constant linear velocity (CLV) mode.

There were several formats developed for recording video on optical discs before the DVD. Optical recording technology was invented by David Paul Gregg and James Russell in 1963 and first patented in 1968. A consumer optical disc data format known as LaserDisc was developed in the United States, and first came to market in Atlanta, Georgia in December 1978. It used much larger discs than the later formats. Due to the high cost of players and discs, consumer adoption of LaserDisc was very low in both North America and Europe, and was not widely used anywhere outside Japan and the more affluent areas of Southeast Asia, such as Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia and Taiwan.

Released in 1987, CD Video used analog video encoding on optical discs matching the established standard 120 mm (4.7 in) size of audio CDs. Video CD (VCD) became one of the first formats for distributing digitally encoded films in this format, in 1993.[13] In the same year, two new optical disc storage formats were being developed. One was the Multimedia Compact Disc (MMCD), backed by Philips and Sony (developers of the CD and CD-i), and the other was the Super Density (SD) disc, supported by Toshiba, Time Warner, Matsushita Electric, Hitachi, Mitsubishi Electric, Pioneer, Thomson, and JVC. By the time of the press launches for both formats in January 1995, the MMCD nomenclature had been dropped, and Philips and Sony were referring to their format as Digital Video Disc (DVD).[14][15] The Super Density logo would later be reused in Secure Digital.

Representatives from the SD camp asked IBM for advice on the file system to use for their disc, and sought support for their format for storing computer data. Alan E. Bell, a researcher from IBM's Almaden Research Center, got that request, and also learned of the MMCD development project. Wary of being caught in a repeat of the costly videotape format war between VHS and Betamax in the 1980s, he convened a group of computer industry experts, including representatives from Apple, Microsoft, Sun Microsystems, Dell, and many others. This group was referred to as the Technical Working Group, or TWG.

On August 14, 1995, an ad hoc group formed from five computer companies (IBM, Apple, Compaq, Hewlett-Packard, and Microsoft) issued a press release stating that they would only accept a single format.[16] The TWG voted to boycott both formats unless the two camps agreed on a single, converged standard. They recruited Lou Gerstner, president of IBM, to pressure the executives of the warring factions. In one significant compromise, the MMCD and SD groups agreed to adopt proposal SD 9, which specified that both layers of the dual-layered disc be read from the same side—instead of proposal SD 10, which would have created a two-sided disc that users would have to turn over.[17] As a result, the DVD specification provided a storage capacity of 4.7 GB for a single-layered, single-sided disc and 8.5 GB for a dual-layered, single-sided disc.[17] The DVD specification ended up similar to Toshiba and Matsushita's Super Density Disc, except for the dual-layer option (MMCD was single-sided and optionally dual-layer, whereas SD was two half-thickness, single-layer discs which were pressed separately and then glued together to form a double-sided disc[15]) and EFMPlus modulation designed by Kees Schouhamer Immink.

Philips and Sony decided that it was in their best interests to end the format war, and agreed to unify with companies backing the Super Density Disc to release a single format, with technologies from both. After other compromises between MMCD and SD, the computer companies through TWG won the day, and a single format was agreed upon. The TWG also collaborated with the Optical Storage Technology Association (OSTA) on the use of their implementation of the ISO-13346 file system (known as Universal Disk Format) for use on the new DVDs.

In September 1995, Samsung announced it would start mass-producing DVDs by September 1996.[18] The format launched on November 1, 1996 in Japan, mostly only with music video releases. The first major releases from Warner Home Video arrived on December 20, 1996, with four titles being available.[lower-alpha 1][4]

Adoption

Movie and home entertainment distributors adopted the DVD format to replace the ubiquitous VHS tape as the primary consumer video distribution format.[19] They embraced DVD as it produced higher quality video and sound, provided superior data lifespan, and could be interactive. Interactivity on LaserDiscs had proven desirable to consumers, especially collectors. When LaserDisc prices dropped from approximately $100 per disc to $20 per disc at retail, this luxury feature became available for mass consumption. Simultaneously, the movie studios decided to change their home entertainment release model from a rental model to a for purchase model, and large numbers of DVDs were sold.

At the same time, a demand for interactive design talent and services was created. Movies in the past had uniquely designed title sequences. Suddenly every movie being released required information architecture and interactive design components that matched the film's tone and were at the quality level that Hollywood demanded for its product.

DVD as a format had two qualities at the time that were not available in any other interactive medium: enough capacity and speed to provide high quality, full motion video and sound, and low cost delivery mechanism provided by consumer products retailers. Retailers would quickly move to sell their players for under $200, and eventually for under $50 at retail. In addition, the medium itself was small enough and light enough to mail using general first class postage. Almost overnight, this created a new business opportunity and model for business innovators to re-invent the home entertainment distribution model. It also gave companies an inexpensive way to provide business and product information on full motion video through direct mail.

Immediately following the formal adoption of a unified standard for DVD, two of the four leading video game console companies (Sega and The 3DO Company) said they already had plans to design a gaming console with DVDs as the source medium.[20] (Sony, despite being one of the developers of the DVD format and eventually the first company to actually release a DVD-based console, stated at the time that they had no plans to use DVD in their gaming systems.[20]) Game consoles such as the PlayStation 2, Xbox, and Xbox 360 use DVDs as their source medium for games and other software. Contemporary games for Windows were also distributed on DVD. Early DVDs were mastered using DLT tape,[21] but using DVD-R DL or +R DL eventually became common.[22] TV DVD combos, combining a standard definition CRT TV or an HD flat panel TV with a DVD mechanism under the CRT or on the back of the flat panel, were also once available for purchase.[23]

Specifications

The DVD specifications created and updated by the DVD Forum are published as so-called DVD Books (e.g. DVD-ROM Book, DVD-Audio Book, DVD-Video Book, DVD-R Book, DVD-RW Book, DVD-RAM Book, DVD-AR (Audio Recording) Book, DVD-VR (Video Recording) Book, etc.).[1][2][3] DVD discs are made up of two discs; normally one is blank, and the other contains data. Each disc is 0.6mm thick, and are glued together to form a DVD disc. The gluing process must be done carefully to make the disc as flat as possible to avoid both birefringence and "disc tilt", which is when the disc is not perfectly flat, preventing it from being read.[24][25]

Some specifications for mechanical, physical and optical characteristics of DVD optical discs can be downloaded as freely available standards from the ISO website.[26] There are also equivalent European Computer Manufacturers Association (Ecma) standards for some of these specifications, such as Ecma-267 for DVD-ROMs.[27] Also, the DVD+RW Alliance publishes competing recordable DVD specifications such as DVD+R, DVD+R DL, DVD+RW or DVD+RW DL. These DVD formats are also ISO standards.[28][29][30][31]

Some DVD specifications (e.g. for DVD-Video) are not publicly available and can be obtained only from the DVD Format/Logo Licensing Corporation (DVD FLLC) for a fee of US$5000.[32][33] Every subscriber must sign a non-disclosure agreement as certain information on the DVD Books is proprietary and confidential.[32]

Discs with multiple layers

Like other optical disc formats before it, a basic DVD disc—known as DVD-5 in the DVD Books, while called Type A in the ISO standard—contains a single data layer readable from only one side. However, the DVD format also includes specifications for three types of discs with additional recorded layers, expanding disc data capacity beyond the 4.7 GB of DVD-5 while maintaining the same physical disc size.

Double-sided discs

Borrowing from the LaserDisc format, the DVD standard includes DVD-10 discs (Type B in ISO) with two recorded data layers such that only one layer is accessible from either side of the disc. This doubles the total nominal capacity of a DVD-10 disc to 9.4 GB, but each side is locked to 4.7 GB. Like DVD-5 discs, DVD-10 discs are defined as single-layer (SL) discs.[26]

Double-sided discs identify the sides as A and B. The disc structure lacks the dummy layer where identifying labels are printed on single-sided discs, so information such as title and side are printed on one or both sides of the non-data clamping zone at the center of the disc.

DVD-10 discs fell out of favor because, unlike dual-layer discs, they require users to manually flip them to access the complete content (a relatively egregious scenario for DVD movies) while offering only a negligible benefit in capacity. Additionally, without a non-data side, they proved harder to handle and store.

Dual-layer discs

Dual-layer discs also employ a second recorded layer, however both are readable from the same side (and unreadable from the other). These DVD-9 discs (Type C in ISO) nearly double the capacity of DVD-5 discs to a nominal 8.5 GB, but fall below the overall capacity of DVD-10 discs due to differences in the physical data structure of the additional recorded layer. However, the advantage of not needing to flip the disc to access the complete recorded data – permitting a nearly contiguous experience for A/V content whose size exceeds the capacity of a single layer – proved a more favorable option for mass-produced DVD movies.

DVD hardware accesses the additional layer (layer 1) by refocusing the laser through an otherwise normally-placed, semitransparent first layer (layer 0). This laser refocus—and the subsequent time needed to reacquire laser tracking—can cause a noticeable pause in A/V playback, the length of which varies between hardware.[34] Studios began printing a standard message on keep cases explaining that this pause is not an indication of a damaged or defective disc.

Dual-layer DVDs are recorded using Opposite Track Path (OTP).[35] Most dual-layer discs are mastered with layer 0 starting at the inside diameter and proceeding outward—as is the case for most optical media, regardless of layer count—while Layer 1 starts at the absolute outside diameter and proceeds inward. Additionally, data tracks are spiraled such that the disc rotates the same direction to read both layers. DVD video DL discs can be mastered slightly differently: a single media stream can be divided between the layers such that layer 1 starts at the same diameter that layer 0 finishes. This modification reduces the visible layer transition pause because after refocusing, the laser remains in place rather than losing additional time traversing the remaining disc diameter.

DVD-9 was the first commercially successful implementation of such technology.

Additional types

DVD-18 discs (Type D in ISO) effectively combines the DVD-9 and DVD-10 disc types by containing four recorded data layers (allocated as two sets of layers 0 and 1) such that only one layer set is accessible from either side of the disc. These discs provide a total nominal capacity of 17.0 GB, with 8.5 GB per side.

The DVD Book also permits an additional disc type called DVD-14: a hybrid double-sided disc with one dual-layer side, one single-layer side, and a total nominal capacity of 12.3 GB.[36] DVD-14 has no counterpart in ISO.[26]

Both of these additional disc types are extremely rare due to their complicated and expensive manufacturing.[36]

![]()

DVD recordable and rewritable

HP initially developed recordable DVD media from the need to store data for backup and transport.[37] DVD recordables are now also used for consumer audio and video recording. Three formats were developed: DVD-R/RW, DVD+R/RW (plus), and DVD-RAM. DVD-R is available in two formats, General (650 nm) and Authoring (635 nm), where Authoring discs may be recorded with CSS encrypted video content but General discs may not.[38]

Although most current DVD writers can write in both the DVD+R/RW and DVD-R/RW formats (usually denoted by "DVD±RW" or the existence of both the DVD Forum logo and the DVD+RW Alliance logo), the "plus" and the "dash" formats use different writing specifications. Most DVD hardware plays both kinds of discs, though older models can have trouble with the "plus" variants.

Some early DVD players would cause damage to DVD±R/RW/DL when attempting to read them.

The form of the spiral groove that makes up the structure of a recordable DVD encodes unalterable identification data known as Media Identification Code (MID). The MID contains data such as the manufacturer and model, byte capacity, allowed data rates (also known as speed), etc..

Dual-layer recording

Dual-layer recording (occasionally called double-layer recording) allows DVD-R and DVD+R discs to store nearly double the data of a single-layer disc—8.5 and 4.7 gigabyte capacities, respectively.[39] The additional capacity comes at a cost: DVD±DLs have slower write speeds as compared to DVD±R. DVD-R DL was developed for the DVD Forum by Pioneer Corporation; DVD+R DL was developed for the DVD+RW Alliance by Mitsubishi Kagaku Media (MKM) and Philips.[40]

Recordable DVD discs supporting dual-layer technology are backward-compatible with some hardware developed before the recordable medium.[40] Many current DVD recorders support dual-layer technology, and while the costs became comparable to single-layer burners over time, blank dual-layer media has remained more expensive than single-layer media.

Capacity

The basic types of DVD (12 cm diameter, single-sided or homogeneous double-sided) are referred to by a rough approximation of their capacity in gigabytes. In draft versions of the specification, DVD-5 indeed held five gigabytes, but some parameters were changed later on as explained above, so the capacity decreased. Other formats, those with 8 cm diameter and hybrid variants, acquired similar numeric names with even larger deviation.

The 12 cm type is a standard DVD, and the 8 cm variety is known as a MiniDVD. These are the same sizes as a standard CD and a mini-CD, respectively. The capacity by surface area (MiB/cm2) varies from 6.92 MiB/cm2 in the DVD-1 to 18.0 MB/cm2 in the DVD-18.

Each DVD sector contains 2,418 bytes of data, 2,048 bytes of which are user data. There is a small difference in storage space between + and - (hyphen) formats:

| Designation | Sides | Layers (total) | Diameter (cm) | Capacity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (GB) | ||||||

| DVD-1[43] | SS SL | 1 | 1 | 8 | 1.46 | |

| DVD-2 | SS DL | 1 | 2 | 8 | 2.65 | |

| DVD-3 | DS SL | 2 | 2 | 8 | 2.92 | |

| DVD-4 | DS DL | 2 | 4 | 8 | 5.31 | |

| DVD-5 | SS SL | 1 | 1 | 12 | 4.70 | |

| DVD-9 | SS DL | 1 | 2 | 12 | 8.54 | |

| DVD-10 | DS SL | 2 | 2 | 12 | 9.40 | |

| DVD-14[36] | DS SL+DL | 2 | 3 | 12 | 13.24 | |

| DVD-18 | DS DL | 2 | 4 | 12 | 17.08 | |

| Designation | Sides | Layers (total) | Diameter (cm) | Capacity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (GB) | ||||||

| DVD-R | SS SL (1.0) | 1 | 1 | 12 | 3.95 | |

| DVD-R | SS SL (2.0) | 1 | 1 | 12 | 4.70 | |

| DVD-RW | SS SL | 1 | 1 | 12 | 4.70 | |

| DVD+R | SS SL | 1 | 1 | 12 | 4.70 | |

| DVD+RW | SS SL | 1 | 1 | 12 | 4.70 | |

| DVD-R | SS DL | 1 | 2 | 12 | 8.50 | |

| DVD-RW | SS DL | 1 | 2 | 12 | 8.54 | |

| DVD+R | SS DL | 1 | 2 | 12 | 8.54 | |

| DVD+RW | SS DL | 1 | 2 | 12 | 8.54 | |

| DVD-RAM | SS SL | 1 | 1 | 8 | 1.46* | |

| DVD-RAM | DS SL | 2 | 1 | 8 | 2.47* | |

| DVD-RAM | SS SL (1.0) | 1 | 1 | 12 | 2.58 | |

| DVD-RAM | SS SL (2.0) | 1 | 1 | 12 | 4.70 | |

| DVD-RAM | DS SL (1.0) | 2 | 1 | 12 | 5.15 | |

| DVD-RAM | DS SL (2.0) | 2 | 1 | 12 | 9.39* | |

| Type | Sectors | Bytes | KB | MB | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVD-R SL | 2,298,496 | 4,707,319,808 | 4,707,320 | 4,707 | 4.7 |

| DVD+R SL | 2,295,104 | 4,700,372,992 | 4,700,373 | 4,700 | 4.7 |

| DVD-R DL | 4,171,712 | 8,543,666,176 | 8,543,666 | 8,544 | 8.5 |

| DVD+R DL | 4,173,824 | 8,547,991,552 | 8,547,992 | 8,548 | 8.5 |

DVD drives and players

DVD drives are devices that can read DVD discs on a computer. DVD players are a particular type of devices that do not require a computer to work, and can read DVD-Video and DVD-Audio discs.

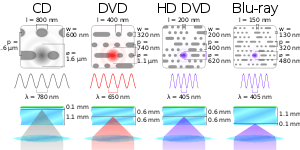

Laser and optics

All three common optical disc media (Compact disc, DVD, and Blu-ray) use light from laser diodes, for its spectral purity and ability to be focused precisely. DVD uses light of 650 nm wavelength (red), as opposed to 780 nm (far-red, commonly called infrared) for CD. This shorter wavelength allows a smaller pit on the media surface compared to CDs (0.74 µm for DVD versus 1.6 µm for CD), accounting in part for DVD's increased storage capacity.

In comparison, Blu-ray Disc, the successor to the DVD format, uses a wavelength of 405 nm (violet), and one dual-layer disc has a 50 GB storage capacity.

Transfer rates

Read and write speeds for the first DVD drives and players were 1,385 kB/s (1,353 KiB/s); this speed is usually called "1×". More recent models, at 18× or 20×, have 18 or 20 times that speed. Note that for CD drives, 1× means 153.6 kB/s (150 KiB/s), about one-ninth as swift.[43][44]

| Drive speed (not rotations) | Data rate | ~Write time (minutes)[45] | Revolutions per minute (constant linear velocity, CLV)[46][47][lower-alpha 2] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mbit/s | MB/s | Single-Layer | Dual-Layer | ||

| 1× | 11 | 1.4 | 57 | 103 | 1400 (inner) 580 (outer)[44] |

| 2× | 22 | 2.8 | 28 | 51 | 2800 (inner) 1160 (outer) |

| 2.4× | 27 | 3.3 | 24 | 43 | 3360 (inner) 1392 (outer) |

| 2.6× | 29 | 3.6 | 22 | 40 | 3640 (inner) 1508 (outer) |

| 3× | 44 | 5.5 | 14 | 26 | 4200 (inner) 2320 (outer) |

| 4× | 44 | 5.5 | 14 | 26 | 5600 (inner) 2900 (outer) |

| 6× | 67 | 8.3 | 9 | 17 | 8400 (inner) 3480 (outer) |

| 8× | 89 | 11.1 | 7 | 13 | 4640 (CAV; no longer uses pure CLV) |

| 10× | 111 | 13.9 | 6 | 10 | 5800 |

| 12× | 133 | 16.6 | 5 | 9 | 6960 |

| 16× | 177 | 22.2 | 4 | 6 | 9280 |

| 18× | 199 | 24.9 | 3 | 6 | 10440 |

| 20× | 222 | 27.7 | 3 | 5 | 11600 |

| 22× | 244 | 30.5 | 3 | 5 | 12760 |

| 24× | 266 | 33.2 | 2 | 4 | 13920 |

DVDs can spin at much higher speeds than CDs - DVDs can spin at up to 32000 RPM vs 23000 for CDs. However, in practice, discs should never be spun at their highest possible speed, to allow for a safety margin and for slight differences between discs. DVD recordable and rewritable discs can be read and written using either constant angular velocity (CAV), constant linear velocity (CLV) or Zoned Constant Linear Velocity (Z-CLV or ZCLV).[48]

Due to the slightly lower data density of dual layer DVDs (4.25 GB instead of 4.7 GB per layer), the required rotation speed is around 10% faster for the same data rate, which means that the same angular speed rating equals equals a 10% higher physical angular rotation speed. For that reason, the increase of reading speeds of dual layer media has stagnated at 12× (constant angular velocity) for half-height optical drives released since around 2005, and slim type optical drives are only able to record dual layer media at 6× (constant angular velocity), while reading speeds of 8× are still supported by such.[49][50][51]

Disc quality measurements

The quality and data integrity of optical media is measureable, which means that future data losses caused by deterioating media can be predicted well in advance by measuring the rate of correctable data errors.[52]

Errors on DVDs are measured as:

- PIE — Pairity Inner Error

- PIF — Pairity Inner Failure

- POE — Pairity Outer Error

- POF — Pairity Outer Failure

A higher rate of errors may indicate a lower media quality, deterioating media, scratches and dirt on the surface, and/or a malfunctioning DVD writer.

PI errors, PI failures and PO errors are correctable, while a PO failure indicates a CRC error, one 2048 byte block (or sector) of data loss, a result of too many consecutive smaller errors.

Additional parameters that can be measured are laser beam focus errors, tracking errors, jitter and beta errors (inconsistencies in lengths of lands and pits).

Support of measuring the disc quality varies among optical drive vendors and models.

DVD-Video

DVD-Video is a standard for distributing video/audio content on DVD media. The format went on sale in Japan on November 1, 1996,[4] in the United States on March 24, 1997 to line up with the 69th Academy Awards that day;[6] in Canada, Central America, and Indonesia later in 1997, and in Europe, Asia, Australia, and Africa in 1998. DVD-Video became the dominant form of home video distribution in Japan when it first went on sale on November 1, 1996, but it shared the market for home video distribution in the United States until June 15, 2003, when weekly DVD-Video in the United States rentals began outnumbering weekly VHS cassette rentals.[55] DVD-Video is still the dominant form of home video distribution worldwide except for in Japan where it was surpassed by Blu-ray Disc when Blu-ray first went on sale in Japan on March 31, 2006.

Security

The Content Scramble System (CSS) is a digital rights management (DRM) and encryption system employed on almost all commercially produced DVD-video discs. CSS utilizes a proprietary 40-bit stream cipher algorithm. The system was introduced around 1996 and was first compromised in 1999.

The purpose of CSS is twofold:

- CSS prevents byte-for-byte copies of an MPEG (digital video) stream from being playable since such copies do not include the keys that are hidden on the lead-in area of the restricted DVD.

- CSS provides a reason for manufacturers to make their devices compliant with an industry-controlled standard, since CSS scrambled discs cannot in principle be played on noncompliant devices; anyone wishing to build compliant devices must obtain a license, which contains the requirement that the rest of the DRM system (region codes, Macrovision, and user operation prohibition) be implemented.[56]

While most CSS-decrypting software is used to play DVD videos, other pieces of software (such as DVD Decrypter, AnyDVD, DVD43, Smartripper, and DVD Shrink) can copy a DVD to a hard drive and remove Macrovision, CSS encryption, region codes and user operation prohibition.

Consumer restrictions

The rise of filesharing has prompted many copyright holders to display notices on DVD packaging or displayed on screen when the content is played that warn consumers of the illegality of certain uses of the DVD. It is commonplace to include a 90-second advertisement warning that most forms of copying the contents are illegal. Many DVDs prevent skipping past or fast-forwarding through this warning.

Arrangements for renting and lending differ by geography. In the U.S., the right to re-sell, rent, or lend out bought DVDs is protected by the first-sale doctrine under the Copyright Act of 1976. In Europe, rental and lending rights are more limited, under a 1992 European Directive that gives copyright holders broader powers to restrict the commercial renting and public lending of DVD copies of their work.

DVD-Audio

DVD-Audio is a format for delivering high fidelity audio content on a DVD. It offers many channel configuration options (from mono to 5.1 surround sound) at various sampling frequencies (up to 24-bits/192 kHz versus CDDA's 16-bits/44.1 kHz). Compared with the CD format, the much higher-capacity DVD format enables the inclusion of considerably more music (with respect to total running time and quantity of songs) or far higher audio quality (reflected by higher sampling rates, greater sample resolution and additional channels for spatial sound reproduction).

DVD-Audio briefly formed a niche market, probably due to the very sort of format war with rival standard SACD that DVD-Video avoided.

Security

DVD-Audio discs employ a DRM mechanism, called Content Protection for Prerecorded Media (CPPM), developed by the 4C group (IBM, Intel, Matsushita, and Toshiba).

Although CPPM was supposed to be much harder to crack than a DVD-Video CSS, it too was eventually cracked, in 2007, with the release of the dvdcpxm tool. The subsequent release of the libdvdcpxm library (based on dvdcpxm) allowed for the development of open source DVD-Audio players and ripping software. As a result, making 1:1 copies of DVD-Audio discs is now possible with relative ease, much like DVD-Video discs.

Successors and decline

In 2006, two new formats called HD DVD and Blu-ray Disc were released as the successor to DVD. HD DVD competed unsuccessfully with Blu-ray Disc in the format war of 2006–2008. A dual layer HD DVD can store up to 30 GB and a dual layer Blu-ray disc can hold up to 50 GB.[57][58]

However, unlike previous format changes, e.g., vinyl to Compact Disc or VHS videotape to DVD, there is no immediate indication that production of the standard DVD will gradually wind down, as they still dominate, with around 75% of video sales and approximately one billion DVD player sales worldwide as of April 2011. In fact, experts claim that the DVD will remain the dominant medium for at least another five years as Blu-ray technology is still in its introductory phase, write and read speeds being poor and necessary hardware being expensive and not readily available.[59][60]

Consumers initially were also slow to adopt Blu-ray due to the cost.[61] By 2009, 85% of stores were selling Blu-ray Discs. A high-definition television and appropriate connection cables are also required to take advantage of Blu-ray disc. Some analysts suggest that the biggest obstacle to replacing DVD is due to its installed base; a large majority of consumers are satisfied with DVDs.[62] The DVD succeeded because it offered a compelling alternative to VHS. In addition, the uniform media size let manufacturers make Blu-ray players (and HD DVD players) backward-compatible, so they can play older DVDs. This stands in contrast to the change from vinyl to CD, and from tape to DVD, which involved a complete change in physical medium. As of 2019 it is still commonplace for studios to issue major releases in "combo pack" format, including both a DVD and a Blu-ray disc (as well as a digital copy). Also, some multi-disc sets use Blu-ray for the main feature, but DVDs for supplementary features (examples of this include the Harry Potter "Ultimate Edition" collections, the 2009 re-release of the 1967 The Prisoner TV series, and a 2007 collection related to Blade Runner). Another reason cited (July 2011) for the slower transition to Blu-ray from DVD is the necessity of and confusion over "firmware updates" and needing an internet connection to perform updates.

This situation is similar to the changeover from 78 rpm shellac recordings to 45 rpm and 33⅓ rpm vinyl recordings. Because the new and old media were virtually the same (a disc on a turntable, played by a needle), phonograph player manufacturers continued to include the ability to play 78s for decades after the format was discontinued.

Manufacturers continue to release standard DVD titles as of 2020, and the format remains the preferred one for the release of older television programs and films. Shows that were shot and edited entirely on film, such as Star Trek: The Original Series, cannot be released in high definition without being re-scanned from the original film recordings. Certain special effects were also updated to appear better in high-definition.[63] Shows that were made between the early 1980s and the early 2000s were generally shot on film, then transferred to cassette tape, and then edited natively in either NTSC or PAL, making high-definition transfers literally impossible as these SD standards were baked into the final cuts of the episodes. Star Trek: The Next Generation is the only such show that has gotten a Blu-Ray release. The process of making high-definition versions of TNG episodes required finding the original film clips, re-scanning them into a computer at high definition, digitally re-editing the episodes from the ground up, and re-rendering new visual effects shots, an extraordinarily labor-intensive ordeal that cost Paramount over $12 million. The project was a financial failure and resulted in Paramount deciding very firmly against giving Deep Space Nine and Voyager the same treatment.[64] However, What We Left Behind included small amounts of remastered Deep Space Nine footage.

DVDs are also facing competition from video on demand services.[65][66][67][68] With increasing numbers of homes having high speed Internet connections, many people now have the option to either rent or buy video from an online service, and view it by streaming it directly from that service's servers, meaning they no longer need any form of permanent storage media for video at all. By 2017, digital streaming services had overtaken the sales of DVDs and Blu-rays for the first time.[69]

Longevity

Longevity of a storage medium is measured by how long the data remains readable, assuming compatible devices exist that can read it: that is, how long the disc can be stored until data is lost. Numerous factors affect longevity: composition and quality of the media (recording and substrate layers), humidity and light storage conditions, the quality of the initial recording (which is sometimes a matter of mutual compatibility of media and recorder), etc.[70] According to NIST, "[a] temperature of 64.4 °F (18 °C) and 40% RH [Relative Humidity] would be considered suitable for long-term storage. A lower temperature and RH is recommended for extended-term storage."[71]

According to the Optical Storage Technology Association (OSTA), "Manufacturers claim lifespans ranging from 30 to 100 years for DVD, DVD-R and DVD+R discs and up to 30 years for DVD-RW, DVD+RW and DVD-RAM."[72]

According to a NIST/LoC research project conducted in 2005–2007 using accelerated life testing, "There were fifteen DVD products tested, including five DVD-R, five DVD+R, two DVD-RW and three DVD+RW types. There were ninety samples tested for each product. [...] Overall, seven of the products tested had estimated life expectancies in ambient conditions of more than 45 years. Four products had estimated life expectancies of 30–45 years in ambient storage conditions. Two products had an estimated life expectancy of 15–30 years and two products had estimated life expectancies of less than 15 years when stored in ambient conditions." The life expectancies for 95% survival estimated in this project by type of product are tabulated below:[70]

| Disc type | 0–15 years | 15–30 years | 30–45 years | over 45 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVD-R | 20% | 20% | 0% | 60% |

| DVD+R | 20% | 0% | 40% | 40% |

| DVD-RW | 0% | 0% | 50% | 50% |

| DVD+RW | 0% | 33.3% | 33.3% | 33.3% |

- 0–15 years

- 15–30 years

- 30–45 years

- over 45 years

See also

- List of computer hardware

- Book type

- Digital video recorder

- Disk-drive performance characteristics

- DVD authoring

- DVD ripper

- DVD region code

- DVD TV game - Interactive movie

- Professional disc

- DVD single

Notes

- The four titles being The Fugitive, Blade Runner: Director's Cut, Eraser, and Assassins.

- Due to the data track circumference of 12cm discs being 2.4 times as long at the outer edge as at the innermost edge of the data area, a constant angular velocity number equals the physical rotation speed the disc has when accessed with the same constant linear velocity number at the outermost edge. This means that the listed CLV (constant linear velocity) speeds at the outer edge equal the same number of rotations per minute as the same CAV (constant angular velocity) rating number.

References

- "DVD FLLC - DVD Format Book". Dvdfllc.co.jp. Archived from the original on April 25, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "DVD FLLC - DVD Format Book". Dvdfllc.co.jp. Archived from the original on February 2, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "BOOKS OVERVIEW". Mpeg.org. Archived from the original on May 1, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- Taylor, Jim (March 21, 1997). "DVD Frequently Asked Questions (with answers!)". Video Discovery. Archived from the original on March 29, 1997. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- Johnson, Lawrence B. (September 7, 1997). "For the DVD, Disney Magic May Be the Key". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 29, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2009.

- Copeland, Jeff B. (March 23, 1997). "Oscar Day Is Also DVD Day". E! Online. Archived from the original on April 11, 1997. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- Staff (March 24, 1997). "Creative Does DVD". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on February 18, 1998. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- Popular Mechanics, June 1997, p. 69;

- Jim Taylor, DVD demystified, McGraw Hill, 1998, 1st edition, p. 405

- Oxford English Dictionary, DVD.

- "DVD Primer". DVD Forum. September 6, 2000. Archived from the original on June 9, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- "DVD Forum's Mission". DVD Forum. January 14, 2010. Archived from the original on May 10, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- "Super Video Compact Disc, A Technical Explanation (PDF)" (PDF). Philips System Standards and Licensing. 1998: 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2008. Retrieved February 13, 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "WCES: The Calm Before the Storm". Next Generation. Imagine Media (3): 18. March 1995.

- "DVD Plagued by Double Standards". Next Generation. Imagine Media (6): 16–17. June 1995.

- "Electronic Giants Battle On". Next Generation. Imagine Media (11): 19. November 1995.

- "DVD: coming soon to your PC?". Computer Shopper. 16 (3): 189. March 1, 1996.

- Souter, Gerry (2017) [1997]. "DVD: The Five-Inch Digital Video Disc". Buying and Selling Multimedia Services. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-136-13437-1.

- Uhlig, Robert (November 22, 2004). "DVD kills the video show as digital age takes over". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on February 16, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "DVD Game Consoles?". Next Generation. No. 18. Imagine Media. June 1996. p. 40.

- "What is DLT? | DVD Authoring". www.hellmanproduction.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- "How to make a proper DVD master | DVD Authoring". www.hellmanproduction.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ISO ISO Freely Available Standards Archived October 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on 2009-07-24

- "Standard ECMA-267". Ecma-international.org. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ISO ISO/IEC 17344:2009, Data interchange on 120 mm and 80 mm optical disc using +R format – Capacity: 4,7 Gbytes and 1,46 Gbytes per side (recording speed up to 16X) Archived April 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on 2009-07-26

- ISO ISO/IEC 25434:2008, Data interchange on 120 mm and 80 mm optical disc using +R DL format – Capacity: 8,55 Gbytes and 2,66 Gbytes per side (recording speed up to 16X) Archived April 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on 2009-07-26

- ISO ISO/IEC 17341:2009, Data interchange on 120 mm and 80 mm optical disc using +RW format – Capacity: 4,7 Gbytes and 1,46 Gbytes per side (recording speed up to 4X) Archived April 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on 2009-07-26

- ISO ISO/IEC 26925:2009, Data interchange on 120 mm and 80 mm optical disc using +RW HS format – Capacity: 4,7 Gbytes and 1,46 Gbytes per side (recording speed 8X) Archived April 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on 2009-07-26

- DVD FLLC (2009) DVD Format Book Archived April 4, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on 2009-08-14

- DVD FLLC (2009) How To Obtain DVD Format/Logo License (2005–2009) Archived March 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on 2009-08-14

- "DVD players benchmark". hometheaterhifi.com. Archived from the original on March 13, 2008. Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- "DVD Studio Pro 4 User Manual". documentation.apple.com. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "DVD-14". AfterDawn Ltd. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- Watson, James. "The recordable DVD clinic". The Register. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2001.

- "DVD Media / DVD-R Media". Tape Resources. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 9, 2011.

- "DVDs" (PDF). PDST Technology in Education. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 2, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- DeMoulin, Robert. "Understanding Dual Layer DVD Recording". BurnWorld.com. Archived from the original on April 21, 2010. Retrieved July 6, 2007.

- "DVD Book A: Physical parameters". Mpeg.org. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- "AVOS Companies – OSFAL Group" (PDF). www.avos.eu. Archived from the original on May 28, 2008.

- Taylor, Jim. "DVD Demystifed FAQ". Dvddemystified.com. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- "Understanding DVD -Recording Speed". Optical Storage Technology Association. Archived from the original on June 11, 2004. Retrieved August 9, 2011.

- The write time is wildly optimistic for higher (>4x) write speeds, due to being calculated from the maximum drive write speed instead of the average drive write speed.

- "Angular Speed of a DVD - The Physics Factbook". hypertextbook.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "DVD-ROM". August 8, 2003. Archived from the original on August 8, 2003.

- "Understanding DVD -Recording Speed". Optical Storage Technology Association. Archived from the original on June 11, 2004. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- Archive of discontinued Hitachi-LG Data Storage optical drives

- Archive of TSSTcorp optical drive manuals

- Pioneer computer drive archive

- QPxTool (error scanning software) - Frequently asked questions

- "QPxTool glossary". qpxtool.sourceforge.io. QPxTool. August 1, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- One DVD “DATA” Sector - LightByte

- Bakalis, Anna (June 20, 2003). "It's unreel: DVD rentals overtake videocassettes". Washington Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2007.

- "IEEE - Copy Protection for DVD Video p.2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2009.

- "What is Blu-ray Disc?". Sony. Archived from the original on December 3, 2009. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- "DVD FAQ: 3.13 – What about the new HD formats?". September 21, 2008. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- "High-Definition Sales Far Behind Standard DVD's First Two Years". Movieweb.com. February 20, 2008. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- "Blu-ray takes 25% Market share". September 21, 2008. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

- Martorana, Robert (November 4, 2009). "Slow Blu-ray Adoption: A Threat to Hollywood's Bottom Line?". Seeking Alpha. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2011.

- "Gates And Ballmer On "Making The Transition"". BusinessWeek. April 19, 2004. Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- "Kirk/Spock STAR TREK To Get All-New HD Spaceships". Aintitcool.com. Archived from the original on December 9, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- Burt, Kayti (February 6, 2017). "Star Trek: DS9 & Voyager HD Blu-Ray Will Likely Never Happen". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- "Are DVDs becoming obsolete?". Electronics.howstuffworks.com. November 1, 2014. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- "Amazon.com: Customer Discussions: When will DVDs be obsolete?". Amazon.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- Romano, Nick. "Is the DVD Becoming Obsolete?". ScreenCrush. Archived from the original on April 12, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- "DVD Going The Way Of VHS In 2016 - CINEMABLEND". Cinemablend.com. June 6, 2014. Archived from the original on April 12, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- Sweney, Mark (January 5, 2017). "Film and TV streaming and downloads overtake DVD sales for first time". Theguardian.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- Final Report: NIST/Library of Congress (LC) Optical Disc Longevity Study Archived February 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Loc.gov, September 2007 (table derived from figure 7)

- Chang, Wo (August 21, 2007). "NIST Digital Media Group: docs/disccare". National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- "Understanding DVD - Disc Longevity". Osta.org. Archived from the original on May 2, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

Further reading

- Bennett, Hugh (April 2004). "Understanding Recordable and Rewritable DVD". Optical Storage Technology Association. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2006.

- Labarge, Ralph (2001). DVD Authoring and Production. Gilroy, California: CMP Books. ISBN 1-57820-082-2.

- Taylor, Jim (2000). DVD Demystified (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0-07-135026-8.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Inside DVD-Video/MPEG Format |

- DVD at Curlie

- Dvddemystified.com: DVD Frequently Asked Questions and Answers

- Dual Layer Explained – Informational Guide to the Dual Layer Recording Process

- YouTube "DVD Gallery": 1997 Toshiba DVD demo disc (segment) — an in-store Toshiba demonstration disc with technical information on the "then-new" DVD format.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to DVD. |