Cysteine

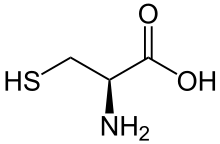

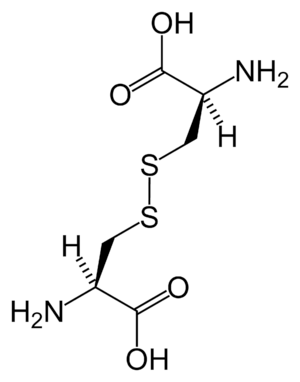

Cysteine (symbol Cys or C;[3] /ˈsɪstiiːn/)[4] is a semiessential[5] proteinogenic amino acid with the formula HO2CCH(NH2)CH2SH. The thiol side chain in cysteine often participates in enzymatic reactions, as a nucleophile. The thiol is susceptible to oxidation to give the disulfide derivative cystine, which serves an important structural role in many proteins. When used as a food additive, it has the E number E920. It is encoded by the codons UGU and UGC.

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Cysteine | |||

| Other names

2-Amino-3-sulfhydrylpropanoic acid | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| Abbreviations | Cys, C | ||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.145 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties[1] | |||

| C3H7NO2S | |||

| Molar mass | 121.15 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | white crystals or powder | ||

| Melting point | 240 °C (464 °F; 513 K) decomposes | ||

| soluble | |||

| Solubility | 1.5g/100g ethanol 19 degC [2] | ||

Chiral rotation ([α]D) |

+9.4° (H2O, c = 1.3) | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |||

Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas | ||

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Cysteine has the same structure as serine, but with one of its oxygen atoms replaced by sulfur; replacing it with selenium gives selenocysteine. Like other natural proteinogenic amino acids, cysteine has l chirality in the older d/l notation based on homology to d- and l-glyceraldehyde. In the newer R/S system of designating chirality, based on the atomic numbers of atoms near the asymmetric carbon, cysteine (and selenocysteine) have R chirality, because of the presence of sulfur (or selenium) as a second neighbour to the asymmetric carbon. The remaining chiral amino acids, having lighter atoms in that position, have S chirality.

Dietary sources

Like other common amino acids, cysteine (and its oxidized dimeric form cystine) is found in high-protein foods. Although classified as a nonessential amino acid, in rare cases, cysteine may be essential for infants, the elderly, and individuals with certain metabolic diseases or who suffer from malabsorption syndromes. Cysteine can usually be synthesized by the human body under normal physiological conditions if a sufficient quantity of methionine is available.

Like other amino acids, in its monomeric "free" form (not as part of a protein) cysteine has an amphoteric character.

Industrial sources

The majority of l-cysteine is obtained industrially by hydrolysis of animal materials, such as poultry feathers or hog hair. Despite widespread belief otherwise, little evidence shows that human hair is used as a source material and its use is explicitly banned in the European Union.[6] Synthetically produced l-cysteine, compliant with Jewish kosher and Muslim halal laws, is also available, albeit at a higher price.[7] The synthetic route involves fermentation using a mutant of E. coli. Degussa introduced a route from substituted thiazolines.[8] Following this technology, l-cysteine is produced by the hydrolysis of racemic 2-amino-Δ2-thiazoline-4-carboxylic acid using Pseudomonas thiazolinophilum.[9]

Biosynthesis

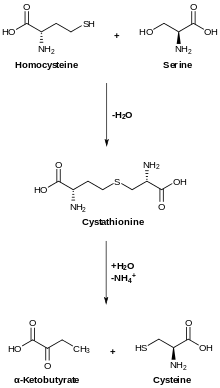

In animals, biosynthesis begins with the amino acid serine. The sulfur is derived from methionine, which is converted to homocysteine through the intermediate S-adenosylmethionine. Cystathionine beta-synthase then combines homocysteine and serine to form the asymmetrical thioether cystathionine. The enzyme cystathionine gamma-lyase converts the cystathionine into cysteine and alpha-ketobutyrate. In plants and bacteria, cysteine biosynthesis also starts from serine, which is converted to O-acetylserine by the enzyme serine transacetylase. The enzyme cysteine synthase, using sulfide sources, converts this ester into cysteine, releasing acetate.[10]

Biological functions

The cysteine sulfhydryl group is nucleophilic and easily oxidized. The reactivity is enhanced when the thiol is ionized, and cysteine residues in proteins have pKa values close to neutrality, so are often in their reactive thiolate form in the cell.[11] Because of its high reactivity, the sulfhydryl group of cysteine has numerous biological functions, and cysteine may have played an important role in the development of primitive life on Earth.[12]

Precursor to the antioxidant glutathione

Due to the ability of thiols to undergo redox reactions, cysteine has antioxidant properties. Its antioxidant properties are typically expressed in the tripeptide glutathione, which occurs in humans and other organisms. The systemic availability of oral glutathione (GSH) is negligible; so it must be biosynthesized from its constituent amino acids, cysteine, glycine, and glutamic acid. While glutamic acid is usually sufficient because amino acid nitrogen is recycled through glutamate as an intermediary, dietary cysteine and glycine supplementation can improve synthesis of glutathione.[13]

Precursor to iron-sulfur clusters

Cysteine is an important source of sulfide in human metabolism. The sulfide in iron-sulfur clusters and in nitrogenase is extracted from cysteine, which is converted to alanine in the process.[14]

Metal ion binding

Beyond the iron-sulfur proteins, many other metal cofactors in enzymes are bound to the thiolate substituent of cysteinyl residues. Examples include zinc in zinc fingers and alcohol dehydrogenase, copper in the blue copper proteins, iron in cytochrome P450, and nickel in the [NiFe]-hydrogenases.[15] The sulfhydryl group also has a high affinity for heavy metals, so that proteins containing cysteine, such as metallothionein, will bind metals such as mercury, lead, and cadmium tightly.[16]

Roles in protein structure

In the translation of messenger RNA molecules to produce polypeptides, cysteine is coded for by the UGU and UGC codons.

Cysteine has traditionally been considered to be a hydrophilic amino acid, based largely on the chemical parallel between its sulfhydryl group and the hydroxyl groups in the side chains of other polar amino acids. However, the cysteine side chain has been shown to stabilize hydrophobic interactions in micelles to a greater degree than the side chain in the nonpolar amino acid glycine and the polar amino acid serine.[17] In a statistical analysis of the frequency with which amino acids appear in different chemical environments in the structures of proteins, free cysteine residues were found to associate with hydrophobic regions of proteins. Their hydrophobic tendency was equivalent to that of known nonpolar amino acids such as methionine and tyrosine (tyrosine is polar aromatic but also hydrophobic[18]), those of which were much greater than that of known polar amino acids such as serine and threonine.[19] Hydrophobicity scales, which rank amino acids from most hydrophobic to most hydrophilic, consistently place cysteine towards the hydrophobic end of the spectrum, even when they are based on methods that are not influenced by the tendency of cysteines to form disulfide bonds in proteins. Therefore, cysteine is now often grouped among the hydrophobic amino acids,[20][21] though it is sometimes also classified as slightly polar,[22] or polar.[5]

While free cysteine residues do occur in proteins, most are covalently bonded to other cysteine residues to form disulfide bonds, which play an important role in the folding and stability of some proteins, usually proteins secreted to the extracellular medium.[23] Since most cellular compartments are reducing environments, disulfide bonds are generally unstable in the cytosol with some exceptions as noted below.

Disulfide bonds in proteins are formed by oxidation of the sulfhydryl group of cysteine residues. The other sulfur-containing amino acid, methionine, cannot form disulfide bonds. More aggressive oxidants convert cysteine to the corresponding sulfinic acid and sulfonic acid. Cysteine residues play a valuable role by crosslinking proteins, which increases the rigidity of proteins and also functions to confer proteolytic resistance (since protein export is a costly process, minimizing its necessity is advantageous). Inside the cell, disulfide bridges between cysteine residues within a polypeptide support the protein's tertiary structure. Insulin is an example of a protein with cystine crosslinking, wherein two separate peptide chains are connected by a pair of disulfide bonds.

Protein disulfide isomerases catalyze the proper formation of disulfide bonds; the cell transfers dehydroascorbic acid to the endoplasmic reticulum, which oxidizes the environment. In this environment, cysteines are, in general, oxidized to cystine and are no longer functional as a nucleophiles.

Aside from its oxidation to cystine, cysteine participates in numerous post-translational modifications. The nucleophilic sulfhydryl group allows cysteine to conjugate to other groups, e.g., in prenylation. Ubiquitin ligases transfer ubiquitin to its pendant, proteins, and caspases, which engage in proteolysis in the apoptotic cycle. Inteins often function with the help of a catalytic cysteine. These roles are typically limited to the intracellular milieu, where the environment is reducing, and cysteine is not oxidized to cystine.

Applications

Cysteine, mainly the l-enantiomer, is a precursor in the food, pharmaceutical, and personal-care industries. One of the largest applications is the production of flavors. For example, the reaction of cysteine with sugars in a Maillard reaction yields meat flavors.[24] l-Cysteine is also used as a processing aid for baking.[25]

In the field of personal care, cysteine is used for permanent-wave applications, predominantly in Asia. Again, the cysteine is used for breaking up the disulfide bonds in the hair's keratin.

Cysteine is a very popular target for site-directed labeling experiments to investigate biomolecular structure and dynamics. Maleimides selectively attach to cysteine using a covalent Michael addition. Site-directed spin labeling for EPR or paramagnetic relaxation-enhanced NMR also uses cysteine extensively.

Reducing toxic effects of alcohol

Cysteine has been proposed as a preventive or antidote for some of the negative effects of alcohol, including liver damage and hangover. It counteracts the poisonous effects of acetaldehyde. Cysteine supports the next step in metabolism, which turns acetaldehyde into acetic acid. In a rat study, test animals received an LD90 dose of acetaldehyde. Those that received cysteine had an 80% survival rate; when both cysteine and thiamine were administered, all animals survived. The control group had a 10% survival rate.[26] No direct evidence indicates its effectiveness in humans who consume alcohol at low levels.

N-Acetylcysteine

N-Acetyl-l-cysteine is a derivative of cysteine wherein an acetyl group is attached to the nitrogen atom. This compound is sold as a dietary supplement, and used as an antidote in cases of acetaminophen overdose.[27]

Sheep

Cysteine is required by sheep to produce wool. It is an essential amino acid that must be taken in from their feed. As a consequence, during drought conditions, sheep produce less wool; however, transgenic sheep that can make their own cysteine have been developed.[28]

Dietary restrictions

The animal-originating sources of l-cysteine as a food additive are a point of contention for people following dietary restrictions such as kosher, halal, vegan, or vegetarian.[29] To avoid this problem, l-cysteine can also be sourced from microbial or other synthetic processes.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cysteine. |

References

- Weast, Robert C., ed. (1981). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (62nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. C-259. ISBN 0-8493-0462-8..

- Belitz, H.-D; Grosch, Werner; Schieberle, Peter (2009-02-27). Food Chemistry. ISBN 9783540699330.

- "Nomenclature and symbolism for amino acids and peptides (IUPAC-IUB Recommendations 1983)", Pure Appl. Chem., 56 (5): 595–624, 1984, doi:10.1351/pac198456050595

- "cysteine - Definition of cysteine in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries - English. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "The primary structure of proteins is the amino acid sequence". The Microbial World. University of Wisconsin-Madison Bacteriology Department. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- "EU Chemical Requirements". Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- "Questions About Food Ingredients: What is L-cysteine/cysteine/cystine?". Vegetarian Resource Group. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Martens, Jürgen; Offermanns, Heribert; Scherberich, Paul (1981). "Facile Synthesis of Racemic Cysteine". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 20 (8): 668. doi:10.1002/anie.198106681.

- Drauz, Karlheinz; Grayson, Ian; Kleemann, Axel; Krimmer, Hans-Peter; Leuchtenberger, Wolfgang; Weckbecker, Christoph (2007). "Amino Acids". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a02_057.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- Hell R (1997). "Molecular physiology of plant sulfur metabolism". Planta. 202 (2): 138–48. doi:10.1007/s004250050112. PMID 9202491.

- Bulaj G, Kortemme T, Goldenberg DP (June 1998). "Ionization-reactivity relationships for cysteine thiols in polypeptides". Biochemistry. 37 (25): 8965–72. doi:10.1021/bi973101r. PMID 9636038.

- Vallee, Yannick; Shalayel, Ibrahim; Ly, Kieu-Dung; Rao, K. V. Raghavendra; Paëpe, Gael De; Märker, Katharina; Milet, Anne (2017-11-08). "At the very beginning of life on Earth: the thiol-rich peptide (TRP) world hypothesis". International Journal of Developmental Biology. 61 (8–9): 471–478. doi:10.1387/ijdb.170028yv. ISSN 0214-6282. PMID 29139533.

- Sekhar, Rajagopal V; Patel, Sanjeet G (2011). "Deficient synthesis of glutathione underlies oxidative stress in aging and can be corrected by dietary cysteine and glycine supplementation". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 94 (3): 847–853. doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.003483. PMC 3155927. PMID 21795440. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- Lill R, Mühlenhoff U (2006). "Iron-sulfur protein biogenesis in eukaryotes: components and mechanisms". Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22: 457–86. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104538. PMID 16824008.

- Lippard, Stephen J.; Berg, Jeremy M. (1994). Principles of Bioinorganic Chemistry. Mill Valley, CA: University Science Books. ISBN 978-0-935702-73-6.

- Baker DH, Czarnecki-Maulden GL (June 1987). "Pharmacologic role of cysteine in ameliorating or exacerbating mineral toxicities". J. Nutr. 117 (6): 1003–10. doi:10.1093/jn/117.6.1003. PMID 3298579.

- Heitmann P (January 1968). "A model for sulfhydryl groups in proteins. Hydrophobic interactions of the cystein side chain in micelles". Eur. J. Biochem. 3 (3): 346–50. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb19535.x. PMID 5650851.

- "A Review of Amino Acids (tutorial)". Curtin University. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- Nagano N, Ota M, Nishikawa K (September 1999). "Strong hydrophobic nature of cysteine residues in proteins". FEBS Lett. 458 (1): 69–71. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01122-9. PMID 10518936.

- Betts, M.J.; R.B. Russell (2003). "Hydrophobic amino acids". Amino Acid Properties and Consequences of Substitutions, In: Bioinformatics for Geneticists. Wiley. Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- Gorga, Frank R. (1998–2001). "Introduction to Protein Structure--Non-Polar Amino Acids". Archived from the original on 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- "Virtual Chembook--Amino Acid Structure". Elmhurst College. Archived from the original on 2012-10-02. Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- Sevier CS, Kaiser CA (November 2002). "Formation and transfer of disulphide bonds in living cells". Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3 (11): 836–47. doi:10.1038/nrm954. PMID 12415301.

- Huang, Tzou-Chi; Ho, Chi-Tang (2001-07-27). Hui, Y. H.; Nip, Wai-Kit; Rogers, Robert (eds.). Meat Science and Applications, ch. Flavors of Meat Products. CRC. pp. 71–102. ISBN 978-0-203-90808-2.

- "Food Ingredients and Colors". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. November 2004. Archived from the original on 2009-05-12. Retrieved 2009-09-06. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help). - Sprince H, Parker CM, Smith GG, Gonzales LJ (April 1974). "Protection against acetaldehyde toxicity in the rat by L-cysteine, thiamin and L-2-methylthiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid". Agents Actions. 4 (2): 125–30. doi:10.1007/BF01966822. PMID 4842541.

- Kanter MZ (October 2006). "Comparison of oral and i.v. acetylcysteine in the treatment of acetaminophen poisoning". Am J Health Syst Pharm. 63 (19): 1821–7. doi:10.2146/ajhp060050. PMID 16990628. S2CID 9209528.

- Powell BC, Walker SK, Bawden CS, Sivaprasad AV, Rogers GE (1994). "Transgenic sheep and wool growth: possibilities and current status". Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 6 (5): 615–23. doi:10.1071/RD9940615. PMID 7569041.

- "Kosher View of L-Cysteine". kashrut.com. May 2003.

Further reading

- Nagano N, Ota M, Nishikawa K (September 1999). "Strong hydrophobic nature of cysteine residues in proteins". FEBS Lett. 458 (1): 69–71. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01122-9. PMID 10518936.

External links

- Cysteine MS Spectrum

- International Kidney Stone Institute

- http://www.chemie.fu-berlin.de/chemistry/bio/aminoacid/cystein en.html

- 952-10-3056-9 Interaction of alcohol and smoking in the pathogenesis of upper digestive tract cancers - possible chemoprevention with cysteine

- Cystine Kidney Stones

- Kosher View of L-Cysteine