Crittenden Compromise

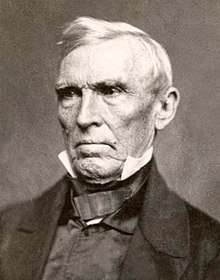

The Crittenden Compromise was an unsuccessful proposal to permanently enshrine slavery in the United States Constitution, and thereby make it unconstitutional for future congresses to end slavery. It was introduced by United States Senator John J. Crittenden (Constitutional Unionist of Kentucky) on December 18, 1860. It aimed to resolve the secession crisis of 1860–1861 that eventually led to the American Civil War by addressing the fears and grievances of Southern pro-slavery factions, and by quashing anti-slavery activities.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Background

The compromise proposed six constitutional amendments and four Congressional resolutions. Crittenden introduced the package on December 18.[1] It was tabled on December 31.

It guaranteed the permanent existence of slavery in the slave states and addressed Southern demands in regard to fugitive slaves and slavery in the District of Columbia. It proposed re-instating the Missouri Compromise (which had been functionally repealed in 1854 by the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and struck down entirely in 1857 by the Dred Scott decision), and extending the compromise line to the west, with slavery prohibited north of the 36° 30′ parallel and guaranteed south of it. The compromise included a clause that it could not be repealed or amended.

The compromise was popular among Southern members of the Senate, but it was generally unacceptable to the Republicans, who opposed the expansion of slavery beyond the states where it already existed into the territories. The opposition of their party's leader, President-elect Abraham Lincoln, was crucial. Republicans said the compromise "would amount to a perpetual covenant of war against every people, tribe, and state owning a foot of land between here and Tierra del Fuego."[2] The only territories south of the line were parts of New Mexico Territory and Indian Territory. There was considerable agreement on both sides that slavery would never flourish in New Mexico. The South refused the House Republicans' proposal, approved by committee on December 29, to admit New Mexico as a state immediately.[3] However, not all opponents of the Crittenden Compromise also opposed further territorial expansion of the United States. The New York Times referred to "the whole future growth of the Republic" and "all the Territory that can ever belong to the United States—the whole of Mexico and Central America." [4]

Components

Amendments to the Constitution

- Slavery would be prohibited in any territory of the United States "now held, or hereafter acquired," north of latitude 36 degrees, 30 minutes line. In territories south of this line, slavery of the African race was "hereby recognized" and could not be interfered with by Congress. Furthermore, property in African slaves was to be "protected by all the departments of the territorial government during its continuance." States would be admitted to the Union from any territory with or without slavery as their constitutions provided.

- Congress was forbidden to abolish slavery in places under its jurisdiction, such as a military post, within a slave state.

- Congress could not abolish slavery in the District of Columbia so long as it existed in the adjoining states of Virginia and Maryland and without the consent of the District's inhabitants. Compensation would be given to owners who refused consent to abolition.

- Congress could not prohibit or interfere with the interstate slave trade.

- Congress would provide full compensation to owners of rescued fugitive slaves. Congress was empowered to sue the county in which obstruction to the fugitive slave laws took place to recover payment; the county, in turn, could sue "the wrong doers or rescuers" who prevented the return of the fugitive.

- No future amendment of the Constitution could change these amendments or authorize or empower Congress to interfere with slavery within any slave state.[5]

Congressional resolutions

- That fugitive slave laws were constitutional and should be faithfully observed and executed.

- That all state laws which impeded the operation of fugitive slave laws, the so-called "Personal liberty laws," were unconstitutional and should be repealed.

- That the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 should be amended (and rendered less objectionable to the North) by equalizing the fee schedule for returning or releasing alleged fugitives and limiting the powers of marshals to summon citizens to aid in their capture.

- That laws for the suppression of the African slave trade should be effectively and thoroughly executed.[5]

Results

President-elect Abraham Lincoln vehemently opposed the Crittenden compromise on grounds that he opposed any policy permitting the continued expansion of slavery.[6] Both the House of Representatives and the Senate rejected Crittenden's proposal. It was part of a series of last-ditch efforts to provide the Southern states with sufficient reassurances to forestall their secession during the final session of Congress prior to the Lincoln administration taking office.

The Crittenden proposals were also discussed at the Peace Conference of 1861, a meeting of more than 100 of the nation's leading politicians, held February 8–27, 1861, in Washington, D.C. The conference, led by former President John Tyler, was the final formal effort of the states to avert the start of war. There too, the Compromise proposals failed, as the provision guaranteeing slave ownership throughout all Western territories and future acquisitions again proved unpalatable.

A February 1861 editorial in the Charleston Courier (Charleston, Missouri) summed up the mood prevalent in Southern-leaning border counties as the Crittenden proposals went down in defeat: "Men at Washington think there is no chance for peace, and indeed we can see but little, everything looks gloomy. The Crittenden resolutions have been voted down again and again. Is there any other proposition which will win, that the South can accept? If not—there comes war—and woe to the wives and daughters of our land; beauty will be but an incentive to crime, and plunder but pay for John Brown raids. Let our citizens be prepared for the worst, it may come."[7] This statement by editor George Whitcomb came in response to a fiery "letter to the editor" excoriating "disunion", from US Representative John William Noell, whose district included Charleston.

In popular culture

The novel Underground Airlines (2016) by Ben Winters is set in an alternate history where the Crittenden Compromise was accepted.[8]

References

- Amendments Proposed in Congress by Senator John J. Crittenden: December 18, 1860 Avalon Project

- James M. McPherson (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. United States of America: Oxford University Press. p. 904 pages. ISBN 0-19-516895-X.

- David M. Potter (1976). The Impending Crisis. Harper & Row. pp. 533–534. ISBN 978-0-06-131929-7.

- "The Crittenden Compromise". The New York Times. February 6, 1861.

- "Cong. Globe, 36th Cong., 2nd Sess. 114 (1860)". Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- https://courses.lumenlearning.com/atd-sanjac-ushistory1/chapter/the-origins-and-outbreak-of-the-civil-war/

- Whitcomb, Geo. (February 1, 1861). "Editorial". Charleston Courier (Charleston, Mo). Charleston, Missouri. p. 2. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

-

Ben Winters (March 14, 2019). "What Do the Make-Believe Bureaucracies of Sci-Fi Novels Say About Us?". The New York Times. p. 14 of the Sunday Book Review. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

I performed a similar maneuver when I was working on my novel 'Underground Airlines' and seeking a historical event that would sweep the Civil War from American history. In the end I needed only to resurrect the Crittenden Compromise, a set of statutes that was really proposed, really debated and really voted down by Congress, thank God, late in 1860.