Cretoxyrhina

Cretoxyrhina (/krɪˌtɒksiˈrhaɪnə/; meaning 'Cretaceous sharp-nose') is an extinct genus of large mackerel shark that lived about 107 to 73 million years ago during the late Albian to late Campanian of the Late Cretaceous period. The type species, C. mantelli, is more commonly referred to as the Ginsu shark, first popularized in reference to the Ginsu knife, as its theoretical feeding mechanism is often compared with the "slicing and dicing" when one uses the knife. Cretoxyrhina is traditionally classified as the likely sole member of the family Cretoxyrhinidae but other taxonomic placements have been proposed, such as within the Alopiidae and Lamnidae.

| Cretoxyrhina | |

|---|---|

| Cretoxyrhina mantelli tooth from New Jersey, USA; Naturhistorisches Museum (Vienna) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Lamniformes |

| Family: | †Cretoxyrhinidae Glückman, 1958 |

| Genus: | †Cretoxyrhina Glückman, 1958 |

| Type species | |

| †Cretoxyrhina mantelli Agassiz, 1835 | |

| Species | |

| Synonyms[7][8][9][10][11] | |

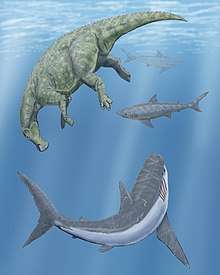

Measuring up to 8 meters (26 ft) in length and weighing up to above 3,400 kilograms (3.3 long tons; 3.7 short tons), Cretoxyrhina was one of the largest sharks of its time. Having a similar appearance and build to the modern great white shark, it was an apex predator in its ecosystem and preyed on a large variety of marine animals including mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, sharks and other large fish, pterosaurs, and occasionally dinosaurs. Its teeth, up to 8 centimeters (3 in) in height, were razor-like and had thick enamel built for stabbing and slicing prey. Cretoxyrhina was also among the fastest-swimming sharks, with hydrodynamic calculations suggesting burst speed capabilities of up to 70 kilometers per hour (43 mph). It has been speculated that Cretoxyrhina hunted by lunging at its prey at high speeds to inflict powerful blows, similar to the great white shark today, and relied on strong eyesight to do so.

Since the late 19th century, several fossils of exceptionally well-preserved skeletons of Cretoxyrhina have been discovered in Kansas. Studies have successfully calculated its life history using vertebrae from some of the skeletons. Cretoxyrhina grew rapidly during early ages and reached sexual maturity at around four to five years of age. Its lifespan has been calculated to extend to nearly forty years. Anatomical analysis of the Cretoxyrhina skeletons revealed that the shark possessed facial and optical features most similar to that in thresher sharks and crocodile sharks and had a hydrodynamic build that suggested the use of regional endothermy.

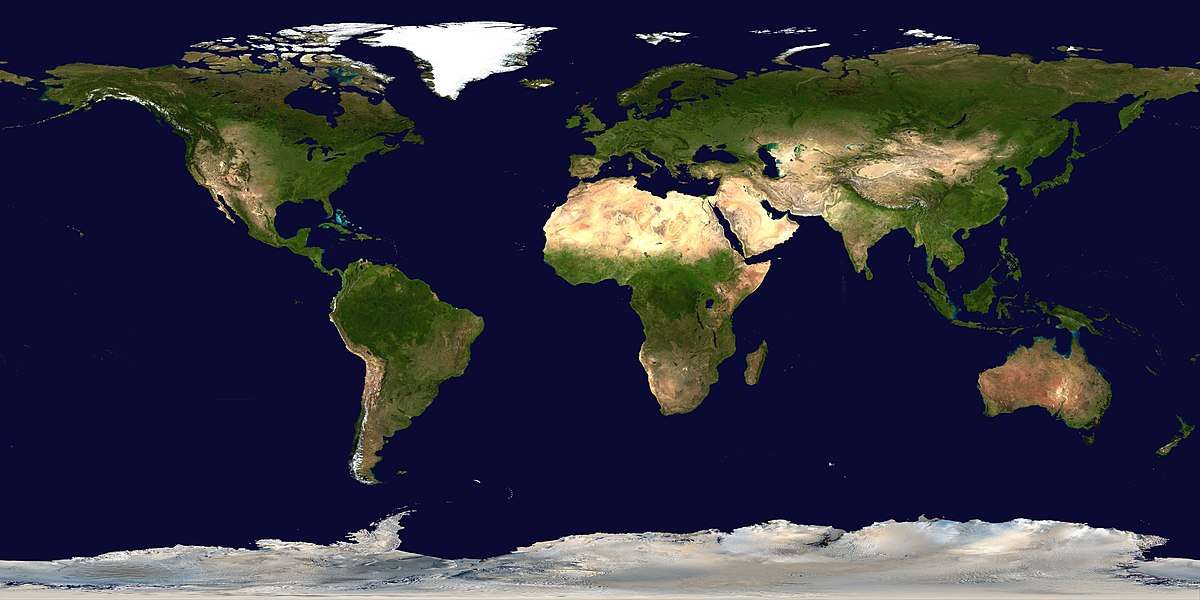

As an apex predator, Cretoxyrhina played a critical role in the marine ecosystems it inhabited. It was a cosmopolitan genus and its fossils have been found worldwide, although most frequently in the Western Interior Seaway area of North America. It preferred mainly subtropical to temperate pelagic environments but was known in waters as cold as 5 °C (41 °F). Cretoxyrhina saw its peak in size by the Coniacian, but subsequently experienced a continuous decline until its extinction during the Campanian. One factor in this demise may have been increasing pressure from competition with predators that arose around the same time, most notably the giant mosasaur Tylosaurus. Other possible factors include the gradual disappearance of the Western Interior Seaway.

Taxonomy

Research history

.jpg)

Cretoxyrhina was first described by the English paleontologist Gideon Mantell from eight C. mantelli teeth he collected from the Southerham Grey Pit near Lewes, East Sussex.[11] In his 1822 book The fossils of the South Downs, he identified them as teeth pertaining to two species of locally-known modern sharks. Mantell identified the smaller teeth as from the common smooth-hound and the larger teeth as from the smooth hammerhead, expressing some hesitation to the latter.[12] In 1843, Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz published the third volume of his book Recherches sur les poissons fossiles, where he reexamined Mantell's eight teeth. Using them and another tooth from the collection of the Strasbourg Museum (whose exact location was unspecified but also came from England), he concluded that the fossils actually pertained to a single species of extinct shark that held strong dental similarities with the three species then classified in the now-invalid genus Oxyrhina, O. hastalis, O. xiphodon, and O. desorii.[13][lower-alpha 1] Agassiz placed the species in the genus Oxyrhina but noted that the much thicker root of its teeth made enough of a difference to be a distinct species and scientifically classified the shark under the taxon Oxyrhina mantellii [lower-alpha 2] and named in honor of Mantell.[13]

During the late 19th century, paleontologists described numerous species that are now synonymized as Cretoxyrhina mantelli. According to some, there may have been as much as almost 30 different synonyms of O. mantelli at the time.[17] Most of these species were derived from teeth that represented variations of C. mantelli but deviated from the exact characteristics of the syntypes.[7] For example, in 1870, French paleontologist Henri Sauvage identified teeth from France that greatly resembled the O. mantelli syntypes from England. The teeth also included lateral cusplets (small enameled cusps that appear at the base of the tooth's main crown), which are not present in the syntypes, which led him to describe the teeth under the species name Otodus oxyrinoides based on the lateral cusplets.[18] In 1873, American paleontologist Joseph Leidy identified teeth from Kansas and Mississippi and described them under the species name Oxyrhina extenta. These teeth were broader and more robust than the O. mantelli syntypes from England.[18][19]

This all changed with the discoveries of some exceptionally well-preserved skeletons of the shark in the Niobrara Formation in West Kansas. Charles H. Sternberg discovered the first skeleton in 1890, which he described in a 1907 paper:[17]

The remarkable thing about this specimen is that the vertebral column, though of cartilaginous material, was almost complete, and that the large number of 250 teeth were in position. When Chas. R. Eastman, of Harvard, described this specimen, it proved so complete as to destroy nearly thirty synonyms used to name the animal, and derived from many teeth found in former times.

— Charles H. Sternberg, Some animals discovered in the fossil beds of Kansas, 1907

_(20765045131).jpg)

Charles R. Eastman published his analysis of the skeleton in 1894. In the paper, he reconstructed the dentition based on the skeleton's disarticulated tooth set. Using the reconstruction, Eastman identified the many extinct shark species and found that their fossils are actually different tooth types of O. mantelli, which he all moved into the species.[18][7] This skeleton, which Sternberg had sold to the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, was destroyed in 1944 by allied bombing during World War II.[18][17] In 1891, Sternberg's son George F. Sternberg discovered a second O. mantelli skeleton now housed in the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History as KUVP 247. This skeleton was reported to measure 6.1 meters (20 ft) in length and consists of a partial vertebral column with skeletal remains of a Xiphactinus as stomach contents and partial jaws with about 150 teeth visible. This skeleton was considered to be one of the greatest scientific discoveries of that year due to the unexpected preservation of cartilage.[17] George F. Sternberg would later discover more O. mantelli skeletons throughout his career. His most notable finds were FHSM VP-323 and FHSM VP-2187, found in 1950[20] and 1965[21] respectively. The former is a partial skeleton consisting of a well-preserved set of jaws, a pair of five gills, and some vertebra while the latter is a near-complete skeleton with an almost complete vertebral column and an exceptionally preserved skull holding much of the cranial elements, jaws, teeth, a set of scales, and fragments of pectoral girdles and fins in their natural positions. Both skeletons are currently housed in the Sternberg Museum of Natural History.[22] In 1968, a collector named Tim Basgall discovered another notable skeleton that, similar to FHSM VP-2187, also consisted of a near-complete vertebral column and a partially preserved skull. This fossil is housed in the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History as KUVP 69102.[23]

In 1958, Soviet paleontologist Leonid Glickman found that the dental design of O. mantelli reconstructed by Eastman made it distinct enough to warrant a new genus—Cretoxyrhina.[18][24] He also identified a second species of Cretoxyrhina based on some of the earlier Cretoxyrhina teeth, which he named Cretoxyrhina denticulata.[25][26] Originally, Glickman designated C. mantelli as the type species, but he abruptly replaced the position with another taxon identified as 'Isurus denticulatus' without explanation in a 1964 paper, a move now rejected as an invalid taxonomic amendment.[8] This nevertheless led Russian paleontologist Viktor Zhelezko to erroneously invalidate the genus Cretoxyrhina in a 2000 paper by synonymizing 'Isurus denticulatus' (and thus the genus Cretoxyrhina as a whole) with another taxon identified as 'Pseudoisurus tomosus'.[lower-alpha 3] Zhelezko also described a new species congeneric with C. mantelli based on tooth material from Kazakhstan, which he identified as Pseudoisurus vraconensis accordingly to his taxonomic reassessment.[8][27] A 2013 study led by Western Australian Museum curator and paleontologist Mikael Siverson corrected the taxonomic error, reinstating the genus Cretoxyrhina and moving 'P'. vraconensis into it.[8] In 2010, British and Canadian paleontologists Charlie Underwood and Stephen Cumbaa described Telodontaspis agassizensis from teeth found in Lake Agassiz in Manitoba that were previously identified as juvenile Cretoxyrhina teeth.[28] This species was reaffirmed into the genus Cretoxyrhina by a 2013 study led by American paleontologist Michael Newbrey using additional fossil material of the same species found in Western Australia.[10]

Between 1997 and 2008, paleontologist Kenshu Shimada published a series of papers where he analyzed the skeletons of C. mantelli including those found by the Sternbergs using modernized techniques to extensively research the possible biology of Cretoxyrhina. Some of his works include the development of more accurate dental,[29] morphological, physiological,[30] and paleoecological reconstructions,[31] ontogenetic studies,[32] and morphological-variable based phylogenetic studies[33] on Cretoxyrhina. Shimada's research on Cretoxyrhina helped shed new light on the understandings of the shark and, through his new methods, other extinct animals.[10]

Etymology

Cretoxyrhina is a portmanteau of the word creto (short for Cretaceous) prefixed to the genus Oxyrhina, which is derived from the Ancient Greek ὀξύς (oxús, "sharp") and ῥίς (rhís, "nose"). When put together they mean "Cretaceous sharp-nose", although Cretoxyrhina is believed to have had a rather blunt snout.[30] The type species name mantelli translates to "from Mantell", which Louis Agassiz named in honor of English paleontologist Gideon Mantell for supplying him the syntypes of the species.[13] The species name denticulata is derived from the Latin word denticulus (small tooth) and suffix āta (possession of), together meaning "having small teeth". This is a reference to the appearance of lateral cusplets in most of the teeth in C. denticulata.[25] The species vraconensis derived from the word vracon and the Latin ensis (from), meaning "from Vracon", which is a reference to the Vraconian substage of the Albian stage in which the species was discovered.[27] The species name agassizensis is derived from the name Agassiz and the Latin ensis (from), meaning "from Agassiz", named after Lake Agassiz where the species was discovered.[28] Coincidentally, the lake itself is named in honor of Louis Agassiz.[34] The common name Ginsu shark, originally coined in 1999 by paleontologists Mike Everhart and Kenshu Shimada, is a reference to the Ginsu knife, as the theoretical feeding mechanisms of C. mantelli was often compared with the "slicing and dicing" when one uses the knife.[35]

Phylogeny and evolution

Cretoxyrhina bore a resemblance to the modern great white shark in size, shape and ecology, but the two sharks are not closely related, and their similarities are a result of convergent evolution.[32] Cretoxyrhina has been traditionally grouped within the Cretoxyrhinidae, a family of lamnoid sharks that traditionally included other genera resulting in a paraphyletic or polyphyletic family.[36] Siverson (1999) remarked that Cretoxyrhinidae was used as a 'wastebasket taxon' for Cretaceous and Paleogene sharks and declared that Cretoxyrhina was the only valid member of the family.[37]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Possible phylogenetic relationship between Cretoxyrhina and modern mackerel sharks based on Shimada (2007)[38] |

Cretoxyrhina contains four valid species: C. vraconensis, C. denticulata, C. agassizensis, and C. mantelli. These species represent a chronospecies.[11] The earliest fossils of Cretoxyrhina are dated about 107 million years old and belong to C. vraconensis.[3] The genus would progress by C. vraconensis evolving into C. denticulata during the Early Cenomanian which evolved into C. agassizensis during the Mid-Cenomanian which in turn evolved into C. mantelli during the Late-Cenomanian. It is notable that C. agassizensis continued until the Mid-Turonian and was briefly contemporaneous with C. mantelli.[11] This progression was characterized by the reduction of lateral cusplets and the increasing size and robustness of teeth.[2][39] The Late-Albian–Mid-Turonian interval sees mainly the reduction of lateral cusplets; C. vraconensis possessed lateral cusplets in all teeth except for a few in the anterior position, which would gradually become restricted only to the back lateroposteriors in adults by the end of the interval in C. mantelli.[2] The Late Cenomanian–Coniacian interval was characterized by a rapid increase in tooth (and body) size, significant decrease of crown/height-crown/width ratio,[1][2] and a transition from a tearing-type to a cutting-type tooth form.[40] Tooth size of C. mantelli individuals inside the Western Interior Seaway peaked around 86 Ma during the latest Coniacian and then begins to slowly decline.[1] In Europe, this peak takes place earlier during the Late Turonian.[11] The youngest fossil of C. mantelli was found in the Bearpaw Formation of Alberta, dating as 73.2 million years old.[5] A single tooth identified as Cretoxyrhina sp. was recovered from the nearby Horseshoe Canyon Formation and dated as 70.44 million years old, suggesting that Cretoxyrhina may have survived into the Maastrichtian. However, the Horseshoe Canyon Formation has only brackish water deposits despite Cretoxyrhina being a marine shark, making a likely possibility that the fossil was reworked from an older layer.[6]

Phylogenetic studies through morphological data conducted by Shimada in 2005 suggested that Cretoxyrhina may alternatively be congeneric with the genus of the modern thresher sharks; the study also stated that the results are premature and may be inaccurate and recommended that Cretoxyrhina is kept within the family Cretoxyrhinidae, mainly citing the lack of substantial data for it during the analysis.[33]

Another possible model for Cretoxyrhina evolution, proposed in 2014 by paleontologist Cajus Diedrich, suggests that C. mantelli was congeneric with the mako sharks of the genus Isurus and was part of an extended Isurus lineage beginning as far the Aptian stage in the Early Cretaceous. According to this model, the Isurus lineage was initiated by 'Isurus appendiculatus' (Cretolamna appendiculata), which evolved into Isurus denticulatus (Cretoxyrhina mantelli [11]) in the Mid-Cenomanian, then 'Isurus mantelli' (Cretoxyrhina mantelli ) at the beginning of the Coniacian, then Isurus schoutedenti during the Paleocene, then Isurus praecursor, where the rest of the Isurus lineage continues.[lower-alpha 4] The study claimed that the absence of corresponding fossils during the Maastrichtian (72–66 Ma) was not a result of a premature extinction of C. mantelli, but merely a gap in the fossil record.[40] Shimada and fellow paleontologist Phillip Sternes published a poster in 2018 which voiced doubt over the credibility of this proposal, noting that the study's interpretation is largely based on data that had been arbitrarily selected and failed to cite either Shimada (1997)[lower-alpha 5] or Shimada (2005), which are key papers regarding the systematic position of C. mantelli.[9]

Biology

Morphology

Dentition

Distinguishing characteristics of Cretoxyrhina teeth include a nearly symmetrical or slanted triangular shape, razor-like and non-serrated cutting edges, visible tooth necks (bourlette), and a thick enamel coating. The dentition of Cretoxyrhina possesses the basic dental characteristics of a mackerel shark, with tooth rows closely spaced without any overlap. Anterior teeth are straight and near-symmetrical, while lateroposterior teeth are slanted. The side of the tooth facing the mouth is convex and possesses massive protuberance and nutrient grooves on the root, whereas the labial side, which faces outwards, is flat or slightly swollen.[29] Juveniles possessed lateral cusplets in all teeth,[28] and C. vraconensis consistently retained them in adulthood.[8] Lateral cusplets were retained only up to all lateroposterior teeth in adulthood in C. denticulata and C. agassizensis and only up to the back lateroposterior teeth in C. mantelli.[28] The lateral cusplets of C. vraconensis[8] and C. denticulata are round, while in C. agassizensis are sharpened to a point.[11] The anterior teeth of C. vraconensis measure 2.1–3.5 centimeters (0.8–1.4 in) in height,[8] while the largest known tooth of C. denticulata measures 3 centimeters (1.2 in).[28] C. mantelli teeth are larger, measuring 3–4 centimeters (1–2 in) in average slant height. The largest tooth discovered from this species may have measured up to 8 centimeters (3 in).[10]

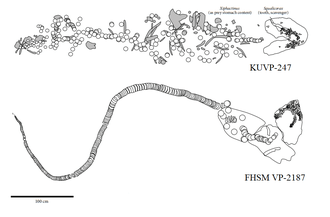

The dentition of C. mantelli is among the best-known of all extinct sharks, thanks to fossil skeletons like FHSM VP-2187, which consists of a near-complete articulated dentition. Other C. mantelli skeletons, such as KUVP-247 and KUVP-69102, also include partial jaws with some teeth in their natural positions, some of which were not present in more complete skeletons like FHSM VP-2187. Using these specimens, the dental formula was reconstructed by Shimada (1997) and revised by Shimada (2002), it was S4.A2.I4.LP11(+?)s1?.a2.i1.lp15(+?). This means that from front to back, C. mantelli had: four symphysials (small teeth located in the symphysis of a jaw), two anteriors, four intermediates, and eleven or more lateroposteriors for the upper jaw and possibly one symphysial, two anteriors, one intermediate, and fifteen or more lateroposteriors for the lower jaw. The structure of the tooth row shows a dental structure suited for a feeding behavior similar to modern mako sharks, having large spear-like anteriors to stab and anchor prey and curved lateroposteriors to cut it to bite-size pieces,[29][41] a mechanism often informally described as "slicing and dicing" by paleontologists.[35] In 2011, paleontologists Jim Bourdon and Mike Everhart reconstructed the dentition of multiple C. mantelli individuals based on their associated tooth sets. They discovered that two of these reconstructions show some notable differences in the size of the first intermediate (I1) tooth and lateral profiles, concluding that these differences could possibly represent sexual dimorphism or individual variations.[42]

.jpg)

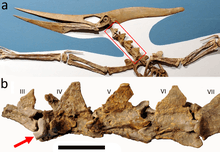

Skull

Analysis of skull and scale patterns suggests that C. mantelli had a conical head with a dorsally flat and wide skull. The rostrum does not extend much forward from the frontal margin of the braincase, suggesting that the snout was blunt.[30] Similar to modern crocodile sharks and thresher sharks, C. mantelli had proportionally large eyes, with the orbit roughly taking up one-third of the entire skull length, giving it acute vision. As a predator, good eyesight was important when hunting the large prey Cretoxyrhina fed on. In contrast, the more smell-reliant contemporaneous anacoracid Squalicorax's less advanced orbital but stronger olfactory processes was more suitable for an opportunistic scavenger.[30][43]

The jaws of C. mantelli were kinetically powerful. They have a slightly looser anterior curvature and a more robust build than that of the modern mako sharks, but otherwise were similar in general shape. The hyomandibula is elongated and was believed to swing laterally, which would allow jaw protrusion and deep biting.[30]

Skeletal anatomy

Most species of Cretoxyrhina are represented only by fossil teeth and vertebra. Like all sharks, the skeleton of Cretoxyrhina was made of cartilage, which is less capable of fossilization than bone. However, fossils of C. mantelli from the Niobrara Formation have been found exceptionally preserved;[44] this was due to the formation's chalk having high contents of calcium, allowing calcification to become more prevalent.[45] When calcified, soft tissue hardens, making it more prone to fossilization.[44]

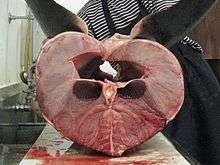

Numerous skeletons consisting of near-complete vertebral columns have been found. The largest vertebra were measured up to 87 millimeters (3 in) in diameter. Two specimens with the best-preserved vertebral columns (FHSM VP-2187 and KUVP 69102) have 218 and 201 centra, respectively, and nearly all vertebra in the column preserved; only portions of the tail tip are missing for both. Estimations of tail length calculates a total vertebral count of approximately 230 centra, which is unique as all known extant mackerel sharks possess a vertebral count of either less than 197 or greater than 282 with none in between. The vertebral centra in the trunk region were large and circular, creating an overall spindle-shaped body with a stocky trunk.[30]

An analysis of a partially complete tail fin fossil shows that Cretoxyrhina had a lunate (crescent-shaped) tail most similar with modern lamnid sharks, whale sharks, and basking sharks. The transition to tail vertebrae is estimated to be between the 140th and 160th vertebrae out of the total 230, resulting in a total tail vertebral count of 70–90 and making up approximately 30–39% of the vertebral column. The transition from precaudal (the set of vertebrae before the tail vertebrae) to tail vertebrae is also marked by a vertebral bend of about 45°, which is the highest possible angle known in extant sharks and is mostly found in fast-swimming sharks, such as lamnids.[46] These properties of the tail, along with other features such as smooth scales parallel to the body axis, a plesodic pectoral fin (a pectoral fin in which cartilage extends throughout, giving it a more secure structure that helps decrease drag), and a spindle-shaped stocky build, show that C. mantelli was capable of fast swimming.[30][46]

Physiology

Thermoregulation

Cretoxyrhina represents one of the earliest forms and possible origins of endothermy in mackerel sharks.[47] Possessing regional endothermy (also known as mesothermy), it may have possessed a build similar to modern regionally endothermic sharks like members of the thresher shark and lamnid families,[47] where red muscles are closer to the body axis compared to ectothermic sharks (whose red muscles are closer to the body circumference), and a system of specialized blood vessels called rete mirabile (Latin for "wonderful nets") is present, allowing metabolic heat to be conserved and exchanged to vital organs. This morphological build allows the shark to be partially warm-blooded,[48] and thus efficiently function in the colder environments where Cretoxyrhina has been found. Fossils have been found in areas where paleoclimatic estimates show a surface temperature as low as 5 °C (41 °F).[47] Regional endothermy in Cretoxyrhina may have been developed in response to increasing pressure from progressive global cooling and competition from mosasaurs and other marine reptiles that had also developed endothermy.[47]

Hydrodynamics and locomotion

Cretoxyrhina possessed highly dense overlapping placoid scales parallel to the body axis and patterned in parallel kneels separated by U-shaped grooves, each groove having a mean width of about 45 micrometers. This formation of scales allows efficient drag reduction and enhanced high-speed velocity capabilities, a morphotype seen only in the fastest known sharks.[30][47] Cretoxyrhina also had the most extreme case of a "Type 4" tail fin, having the highest known Cobb's angle (curvature of tail vertebrae) and tail cartilage angle (49° and 133° respectively) ever recorded in mackerel sharks.[49][47] A "Type 4" tail fin structure represents a build with maximum symmetry of the tail fin lobes, which is most efficient in fast swimming; among sharks, it is only found in lamnids.[49]

A 2017 study by PhD student Humberto Ferron analyzed the relationships between the morphological variables including the skeleton and tail fin of C. mantelli and modeled an average cruising speed of 12 km/h (7.5 mph) and a burst swimming speed of around 70 km/h (43 mph), making Cretoxyrhina possibly one of the fastest sharks known.[47]. For comparison, the modern great white shark has been modeled to reaches speeds of up to 56 km/h (35 mph)[50] and the shortfin mako, the fastest extant shark, has been modeled at a speed of 70 km/h (43 mph).[lower-alpha 6][53]

Life history

Reproduction

Although no fossil evidence for it has been found, it is inferred that Cretoxyrhina was ovoviviparous as all modern mackerel sharks are. In ovoviviparous sharks, young are hatched and grow inside the mother while competing against litter-mates through cannibalism such as oophagy (egg eating). As Cretoxyrhina inhabited oligotrophic and pelagic waters where predators such as large mosasaurs like Tylosaurus and macropredatory fish like Xiphactinus were common, it is likely that it also was an r-selected shark, where many infants are produced to offset high infant mortality rates. Similarly, pelagic sharks such as the great white shark, thresher sharks, mako sharks, porbeagle shark, and crocodile shark produce two to nine infants per litter.[32]

Growth and longevity

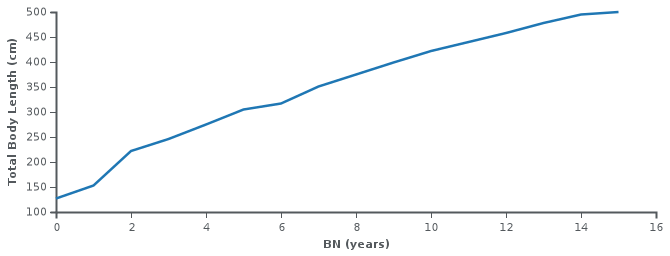

.png)

Like all mackerel sharks, Cretoxyrhina grew a growth ring in its vertebrae every year and is aged through measuring each band; due to the rarity of well-preserved vertebrae, only a few Cretoxyrhina individuals have been aged. In Shimada (1997), a linear equation for calculating the total body length of Cretoxyrhina using the centrum (the body of a vertebra) diameter of a vertebra was developed and is shown below, with TL representing total body length and CD representing centrum diameter (the diameter of each band).[32]

TL = 0.281 + 5.746CD

Using this linear equation, measurements were first conducted on the best-preserved C. mantelli specimen, FHSM VP-2187, by Shimada (2008). The measurements showed a length of 1.28 meters (4 ft) and weight of about 16.3 kilograms (36 lb) at birth, and rapid growth in the first two years of life, doubling the length within 3.3 years. From then on, size growth became steady and gradual, growing a mean estimate of 21.1 centimeters (8 in) per year until its death at around 15 years of age, at which it had grown to 5 meters (16 ft). Using the von Bertalanffy growth model on FHSM VP-2187, the maximum lifespan of C. mantelli was estimated to be 38.2 years. By that age, it would have grown over 7 meters (23 ft) long and weigh as much as 5,500 kilograms (5.4 long tons; 6.1 short tons).[32]

A remeasurement conducted by Newbrey et al. (2013) found that C. mantelli and C. agassizensis reached sexual maturity at around four to five years of age and proposed a possible revision to the measurements of the growth rings in FHSM VP-2187. The lifespan of FHSM VP-2187 and maximum lifespan of C. mantelli was also proposed to be revised to 18 and 21 years respectively using the new measurements. A 2019 study led by Italian scientist Jacopo Amalfitano briefly measured the vertebrae from two C. mantelli fossils and found that the older individual died at around 26 years of age.[11] Measurements were also conducted on other C. mantelli skeletons and a vertebra of C. agassizensis, yielding results of similar rates of rapid growth in early stages of life.[10] Such rapid growth within mere years could have helped Cretoxyrhina better survive by quickly phasing out of infancy and its vulnerabilities, as a fully grown adult would have few natural predators.[32] The study also identified a syntype tooth of C. mantelli from England and calculated the individual's maximum length of 8 meters (26 ft), making the tooth the largest known specimen yet.[10][lower-alpha 7]

The graph below represents the length growth per year of FHSM VP-2187 according to Shimada (2008)[lower-alpha 8][32]

Paleobiology

Prey relationships

The powerful kinetic jaws, high-speed capabilities, and large size of Cretoxyrhina suggest a very aggressive predator.[30][31] Cretoxyrhina's association with a diverse number of fossils showing signs of devourment confirms that it was an active apex predator that fed on much of the variety of marine megafauna in the Late Cretaceous.[31][55] The highest trophic level it occupied was a position shared only with large mosasaurs such as Tylosaurus during the latter stages of the Late Cretaceous. It played a critical role in many marine ecosystems.[55]

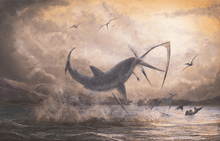

Cretoxyrhina mainly preyed on other active predators including ichthyodectids (a type of large fish that includes Xiphactinus),[31] plesiosaurs,[31][56] turtles,[57] mosasaurs,[31][58][35] and other sharks.[31] Most fossils of Cretoxyrhina feeding upon other animals consist of large and deep bite marks and punctures on bones, occasionally with teeth embedded in them.[35] Isolated bones of mosasaurs and other marine reptiles that have been partially dissolved by digestion, or found in coprolites, are also examples of Cretoxyrhina feeding.[35][58] There are a few skeletons of Cretoxyrhina containing stomach contents known, including a large C. mantelli skeleton (KUVP 247) which possesses skeletal remains of the large ichthyodectid Xiphactinus and a mosasaur in its stomach region.[31] Cretoxyrhina may have occasionally fed on pterosaurs, evidenced by a set of cervical vertebrae of a Pteranodon from the Niobrara Formation with a C. mantelli tooth lodged deep between them. Although it cannot be certain if the fossil itself was a result of predation or scavenging, it was likely that Pteranodon and similar pterosaurs were natural targets for predators like Cretoxyrhina, as they would routinely enter water to feed and thus be well within reach.[59][60]

Although Cretoxyrhina was mainly an active hunter, it was also an opportunistic feeder and may have scavenged from time to time. Many fossils with Cretoxyrhina feeding marks show no sign of healing, an indicator of a deliberate predatory attack on a live animal, leading to the possibility that at least some of the feeding marks were made from scavenging.[31] Remains of partial skeletons of dinosaurs like Claosaurus and Niobrarasaurus show signs of feeding and digestion by C. mantelli. They were likely scavenged carcasses swept into the ocean due to the paleogeographical location of the fossils being that of an open ocean.[61][62]

Hunting strategies

The hunting strategies of Cretoxyrhina are not well documented because many fossils with Cretoxyrhina feeding marks cannot be distinguished between predation or scavenging. If they were indeed a result of the former, that would mean that Cretoxyrhina most likely employed hunting strategies involving a main powerful and fatal blow similar to ram feeding seen in modern requiem sharks and lamnids. A 2004 study by shark experts Vittorio Gabriotti and Alessandro De Maddalena observed that the modern great white shark reaching lengths of greater than 4 meters (13 ft) commonly ram its prey with massive velocity and strength to inflict single fatal blows, sometimes so powerful that prey would be propelled out of the water by the impact's force. As Cretoxyrhina possessed a robust stocky build capable of fast swimming, powerful kinetic jaws like the great white shark, and reaches lengths similar to or greater than it, a hunting style like this would be likely.[56]

Paleoecology

Range and distribution

Cretoxyrhina had a cosmopolitan distribution with fossils having been found worldwide. Notable locations include North America, Europe,[63] Israel,[64] and Kazakhstan.[8] Cretoxyrhina mostly occurred in temperate and subtropical zones.[2] It has been found in latitudes as far north as 55° N, where paleoclimatic estimates calculate an average sea surface temperature of 5–10 °C (41–50 °F). Fossils of Cretoxyrhina are most well known in the Western Interior Seaway area,[64] which is now the central United States and Canada.[65] During a speech in 2012, Mikael Siverson noted that Cretoxyrhina individuals living offshore were usually larger than those inhabiting the Western Interior Seaway, some of the offshore C. mantelli fossils yielding total lengths of up to 8 meters (26 ft), possibly 9 meters (30 ft).[66]

Habitat

Cretoxyrhina inhabited mainly temperate to subtropical pelagic oceans. A tooth of Cretoxyrhina found in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation in Alberta (a formation where the only water deposits found consist of brackish water and no oceans) suggests that it may have, on occasion, swum into partially fresh-water estuaries and similar bodies of water. However, a rework from an underlying layer may be a more likely explanation of such occurrence.[67] The climate of marine ecosystems during the temporal range of Cretoxyrhina was generally much warmer than modern day due to higher atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases influenced by the shape of the continents at the time.[68]

The interval during the Cenomanian and Turonian of 97–91 Ma saw a peak in sea surface temperatures averaging over 35 °C (95 °F) and bottom water temperatures around 20 °C (68 °F), about 7–8 °C (45–46 °F) warmer than modern day.[68] Around this time, Cretoxyrhina coexisted with a radiating increase in diversity of fauna like mosasaurs.[69] This interval also included a rise in global δ13C levels, which marks significant depletion of oxygen in the ocean, and caused the Cenomanian-Turonian anoxic event.[68] Although this event led to the extinction of as much as 27% of marine invertebrates,[70] vertebrates like Cretoxyrhina were generally unaffected.[71] The rest of the Cretaceous saw a progressive global cooling of earth's oceans, leading to the appearance of temperate ecosystems and possible glaciation by the Early Maastrichtian.[68] Subtropical areas retained high biodiversity of all taxa, while temperate ecosystems generally had much lower diversity. In North America, subtropical provinces were dominated by sharks, turtles, and mosasaurs such as Tylosaurus and Clidastes, while temperate provinces were mainly dominated by plesiosaurs, hesperornithid seabirds, and the mosasaur Platecarpus.[72]

Competition

Cretoxyrhina lived alongside many predators that shared a similar trophic level in a diverse pelagic ecosystem during the Cretaceous.[55] Most of these predators included large marine reptiles, some of which already occupied the highest trophic level when Cretoxyrhina first appeared.[86] During the Albian to Turonian, about 107 to 91 Ma, Cretoxyrhina was contemporaneous and coexisted with Mid-Cretaceous pliosaurs. Some of these pliosaurs included Megacephalosaurus, which attained lengths of 9 meters (30 ft).[87] By the Mid-Turonian, about 91 Ma, pliosaurs became extinct.[71][88] It is thought that the radiation of sharks like Cretoxyrhina may have been a major contributing factor to the acceleration of their extinction.[89] The ecological void they left was quickly filled by emerging mosasaurs, which also came to occupy the highest trophic levels.[90] Large mosasaurs like Tylosaurus, which reached in excess of 14 meters (46 ft) in length,[42] may have competed with Cretoxyrhina, and evidence of interspecific interactions such as bite marks from either have been found.[31] There were also many sharks that occupied a similar ecological role with Cretoxyrhina such as the cardabiodontids Cardabiodon[10] and Dwardius, the latter showing evidence of direct competition with C. vraconensis based on intricate distribution patterns between the two.[81]

A 2010 study by paleontologists Corinne Myers and Bruce Lieberman on competition in the Western Interior Seaway used quantitative analytical techniques based on Geographical Information Systems (GIS) and tectonic reconstructions to reconstruct the theoretical competitive relationships between ten of the most prevalent and abundant marine vertebrates of the region, including Cretoxyrhina. Their calculations determined that Cretoxyrhina was likely to have faced the most competition with Squalicorax falcatus, Squalicorax kaupi, and Tylosaurus spp., but was unlikely to face competition from other predators such as Platecarpus spp. or Xiphactinus spp.. The study also concluded that none of the competitive relationships were severe enough to apply candidate competitive replacement (CCR), which is when a species' distribution is affected due to being outcompeted by another.[91]

Extinction

The causes of the extinction of Cretoxyrhina are uncertain. What is known is that it declined slowly over millions of years.[2] Since its peak in size during the Coniacian, the size[1] and distribution[2] of Cretoxyrhina fossils gradually declined until its eventual demise during the Campanian.[1] Siverson and Lindgren (2005) noted that the age of the youngest fossils of Cretoxyrhina differed between continents. In Australia, the youngest Cretoxyrhina fossils were dated approximately 83 Ma during the Santonian, while the youngest North American fossils known at the time (which were dated in the Early Campanian) were at least two million years older than the youngest fossils in Europe. The differences between ages suggests that Cretoxyrhina may have become locally extinct in such areas over time until the genus as a whole went extinct.[2]

It has been noted that the decline of Cretoxyrhina coincides with the rise of newer predators such as Tylosaurus, suggesting that increasing pressure from competition with the mosasaur and other predators of similar trophic levels may have played a major contribution to Cretoxyrhina 's decline and eventual extinction. Another possible factor was the gradual shallowing and shrinking of the Western Interior Seaway, which would have led to the disappearance of the pelagic environments preferred by the shark; this factor does not explain the decline and extinction of Cretoxyrhina elsewhere.[42] It has been suggested that the extinction of Cretoxyrhina may have helped the further increase the diversity of mosasaurs.[90]

Notes

- These are now identified as Cosmopolitodus hastalis and Isurus desori;[14] Oxyrhina xiphodon is now considered conspecific with Cosmopolitodus hastalis.[15]

- The original spelling made by Agassiz ended with -ii. Later authors dropped the extra letter, spelling it as mantelli. Although this is a clear misspelling, it is maintained as the valid spelling of the species according to ICZN Article 33.4 due to its predominant usage over the original.[16]

- This taxon is a nomen dubium whose referred specimens now represent Cardabiodon and Dwardius.[8]

- 'Isurus appendiculatus' and 'Isurus mantelli' are scientific names proposed and used by Diedrich (2014). The original and more widely accepted scientific names of these taxa are shown in parenthesis.[40]

- Shimada (1997) is cited in Diedrich (2014); the latter failed to use the citation in any of his claims regarding the systematic placement of C. mantelli, using it only in stratigraphic and historical notes.[40]

- These swimming speed estimates were calculated based on hydrodynamic models. However, some research suggests that living fish may be incapable of swimming up to such calculated rates due to physiological limitations unforseen by such hydrodynamic modeling. For example, Svendsen et al., (2016) found that accelerometer tags and high-speed video analyses suggest maximum speeds of marlin are closer 10–15 m/s (22–34 mph) contrary to 35 m/s (78 mph) estimates calculated from traditional hydrodynamic modeling, as speeds higher than the former were predicted to cause serious damage to fin tissue. Other fast-swimming fish were also observed to have similar limitations.[51] Likewise, Semmens et al., (2019) observed that living great white sharks reach maximum speeds of 6.5 m/s (15 mph) when attacking seals.[52]

- This syntype is in the collection of the British Museum of Natural History cataloged as NHMUK PV OR 4498.[54] This was not mentioned in Newbrey et al. (2013).[10]

- The chart is based only on vertebrae from FHSM VP-2187. It does not represent the genus Cretoxyrhina as a whole.[32]

- This map shows only select localities mentioned in scientific literature. It does not represent all findings of Cretoxyrhina.

See also

- Prehistoric fish

- List of prehistoric cartilaginous fish

References

- Kenshu Shimada (1997). "Stratigraphic Record of the Late Cretaceous Lamniform Shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Agassiz), in Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 100 (3/4): 139–149. doi:10.2307/3628002. JSTOR 3628002.

- Mikael Siverson and Johan Lindgren (2005). "Late Cretaceous sharks Cretoxyrhina and Cardabiodon from Montana, USA" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- David Ward (2009). Fossils of the Gault Clay – Sharks and Rays. The Paleontological Association. pp. 279–299.

- J.G. Ogg and L.A. Hinnov (2012). Cretaceous. The Geologic Time Scale 2012. pp. 793–853. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-59425-9.00027-5. ISBN 9780444594259.

- Todd Cook, Eric Brown, Patricia E. Ralrick, and Takuya Konish. (2017). "A late Campanian euselachian assemblage from the Bearpaw Formation of Alberta, Canada: some notable range extensions". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 54 (9): 973–980. Bibcode:2017CaJES..54..973C. doi:10.1139/cjes-2016-0233. hdl:1807/77762.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Derek William Larson, Donald B. Brinkman, and Phil R. Bell (2010). "Faunal assemblages from the upper Horseshoe Canyon Formation, an early Maastrichtian cool-climate assemblage from Alberta, with special reference to the Albertosaurus sarcophagus bonebed". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 47 (9): 1159–1181. Bibcode:2010CaJES..47.1159L. doi:10.1139/E10-005.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Charles R. Eastman (1894). "Beiträge zur Kenntniss der Gattung Oxyrhina: mit besonderer Berücksichtigung von Oxyrhina mantelli Agassiz" [Contributions to the knowledge of the genus Oxyrhina: with special reference to Oxyrhina mantelli Agassiz]. Palaeontographica (in German). E. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung: 149–191.

- Mikael Siverson, David John Ward, Johan Lindgren, and L. Scott Kelly (2013). "Mid-Cretaceous Cretoxyrhina (Elasmobranchii) from Mangyshlak, Kazakhstan and Texas, USA". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 37 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/03115518.2012.709440.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Phillip Sternes and Kenshu Shimada (2018), Caudal fin of the Late Cretaceous shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Lamniformes: Cretoxyrhinidae), morphometrically compared to that of extant lamniform sharks, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-12-05, retrieved 2018-12-05

- Michael G. Newbrey, Mikael Siversson, Todd D. Cook, Allison M. Fotheringham, and Rebecca L. Sanchez (2013). "Vertebral Morphology, Dentition, Age, Growth, and Ecology of the Large Lamniform Shark Cardabiodon ricki". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 60 (4): 877–897. doi:10.4202/app.2012.0047.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jacopo Amalfitano; Luca Giusberti; Eliana Fornaciari; Fabio Marco Dalla Vicchia; Valeria Luciani; Jürgen Kriwet; Giorgio Carnevale (2019). "Large deadfall of the 'ginsu' shark Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Agassiz, 1835) (Neoselachii, Lamniformes) from the Upper Cretaceous of northeastern Italy". Cretaceous Research. 98 (June 2019): 250–275. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.02.003.

- Gideon Mantell; Mary Ann Mantell (1822). The fossils of the South Downs; or illustrations of the geology of Sussex. Lupton Relfe. doi:10.3931/e-rara-16021.

- Louis Agassiz (1833–1843) [1838]. Recherches sur les poissons fossiles (in French). 3. Museum of Comparative Zoology.

- László Kocsis (2009). "Central Paratethyan shark fauna (Ipolytarnóc, Hungary)". Geologica Carpathica. 58 (1): 27–40. Archived from the original on 2018-11-25. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- "Additions to and a review of the Miocene Shark and Ray fauna of Malta". The Central Mediterranean Naturalist. 3 (3): 131–146.

- Bruno Cahuzac, Sylvain Adnet, Cappetta Henri, and Romain Vullo (2007). "Les espèces et genres de poissons sélaciens fossiles (Crétacé, Tertiaire) créés dans le Bassin d'Aquitaine ; recensement, taxonomie" [The fossil species and genera of Selachians fishes (Cretaceous, Tertiary) created in the Aquitaine Basin ; inventory, taxonomics]. Bulletin de la Société Linnéenne de Bordeaux (in French). 142 (45): 3–43.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mike Everhart (2002). "A Giant Ginsu Shark". Oceans of Kansas. Archived from the original on 2018-11-11. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- Jim Bourdon. "Cretoxyrhina". Archived from the original on 2018-11-11. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- Joseph Leidy (1873). "Fossil Vertebrates". Contributions to the Extinct Vertebrate Fauna of the Western Territories. 1: 302–303.

- "FHSM VP 323". Fort Hays State University's Sternberg Museum of Natural History.

- "FHSM VP 2187". Fort Hays State University's Sternberg Museum of Natural History.

- Mike Everhart (1999). "Large Sharks in the Western Interior Sea". Oceans of Kansas. Archived from the original on 2018-07-04. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- "Kansas University Vertebrate Paleontology Database". Kansas University Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum.

- E. V. Popov (2016). "An annotated bibliography of the Soviet paleoichthyologist Leonid Glickman (1929–2000)" (PDF). Proceedings of the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 320 (1): 25–49. doi:10.31610/trudyzin/2016.320.1.25. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-11-11. Retrieved 2018-11-10.

- Leonid Glickman (1958). "Rates of evolution in Lamoid sharks" (PDF). Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR (in Russian). 123: 568–571.

- W. James Kennedy, Christopher King, and David J. Ward (2008). "The Upper Albian and Lower Cenomanian succession at Kolbay, eastern Mangyshlak, southwest Kazakhstan". Bulletin de l'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belqique, Sciences de la Terre. 78: 117–147.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- V.I. Zhelezko (2000). "The evolution of teeth systems of sharks of Pseudoisurus Gluckman, 1957 genus – the biggest pelagic sharks of Eurasia" (PDF). Materialy Po Stratigrafii I Paleontologii Urala (in Russian). 1 (4): 136–141.

- Charlie J. Underwood and Stephen L. Cumbaa (2009). "Chondrichthyans from a Cenomanian (Late Cretaceous) bonebed, Saskatchewan, Canada". Palaeontology. 53 (4): 903–944. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00969.x.

- Kenshu Shimada (1997). "Dentition of the Late Cretaceous lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli from the Niobrara Chalk of Kansas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (2): 269–279. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10010974.

- Kenshu Shimada (1997). "Skeletal Anatomy of the Late Cretaceous Lamniform Shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli, from the Niobrara Chalk in Kansas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (4): 642–652. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10011014. JSTOR 4523854.

- Kenshu Shimada (1997). "Paleoecological relationships of the Late Cretaceous lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Agassiz)". Journal of Paleontology. 71 (5): 926–933. doi:10.1017/S002233600003585X.

- Kenshu Shimada (2008). "Ontogenetic parameters and life history strategies of the late Cretaceous lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli, based on vertebral growth increments". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28: 21–33. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[21:OPALHS]2.0.CO;2.

- Kenshu Shimada (2005). "Phylogeny of lamniform sharks (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii) and the contribution of dental characters to lamniform systematics". Paleontological Research. 9: 55–72. doi:10.2517/prpsj.9.55.

- Upham, Warren (1880). The Geology of Central and Western Minnesota. A Preliminary Report. [From the General Report of Progress for the Year 1879.]. St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S.A.: The Pioneer Press Co. p. 18. From p. 18: "Because of its relation to the retreating continental ice-sheet it is proposed to call this Lake Agassiz, in memory of the first prominent advocate of the theory that the drift was produced by land-ice."

- Mike Everhart (2009). "Cretoxyrhina mantelli, the Ginsu Shark". Oceans of Kansas. Archived from the original on 2018-04-24. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- J. G. Maisey (2012). "What is an 'elasmobranch'? The impact of palaeontology in understanding elasmobranch phylogeny and evolution". Journal of Fish Biology. 80 (5): 918–951. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2012.03245.x. PMID 22497368.

- Mikael Siverson (1999). "A new large lamniform shark from the uppermost Gearle Siltstone (Cenomanian, Late Cretaceous) of Western Australia". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences. 90: 49–66. doi:10.1017/S0263593300002509.

- Kenshu Shimada (2007). "Skeletal and Dental Anatomy of Lamniform shark Cretalamna appendiculata, from Upper Cretaceous Niobrara Chalk of Kansas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (3): 584–602. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[584:SADAOL]2.0.CO;2.

- Mark Wilson, Mark V.H. Wilson, Alison M. Murray, A. Guy Plint, Michael G. Newbrey, and Michael J. Everhart (2013). "A high-latitude euselachian assemblage from the early Turonian of Alberta, Canada". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 11 (5): 555–587. doi:10.1080/14772019.2012.707990.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- C. G. Diedrich (2014). "Skeleton of the Fossil Shark Isurus denticulatus from the Turonian (Late Cretaceous) of Germany – Ecological Coevolution with Prey of Mackerel Sharks". Paleontology Journal. 2014: 1–20. doi:10.1155/2014/934235.

- Kenshu Shimada (2002). "Dental homologies in lamniform sharks (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii)". Journal of Morphology. 251 (1): 38–72. doi:10.1002/jmor.1073. PMID 11746467.

- Jim Bourdon and Michael Everhart (2011). "Analysis of an associated Cretoxyrhina mantelli dentition from the Late Cretaceous (Smoky Hill Chalk, Late Coniacian) of western Kansas" (PDF). Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 114 (1–2): 15–32. doi:10.1660/062.114.0102. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-04-04. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- Kenshu Shimada and David J. Cicimurri (2005). "Skeletal anatomy of the Late Cretaceous shark, Squalicorax (Neoselachii, Anacoracidae)". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 79 (2): 241–261. doi:10.1007/BF02990187.

- Mike Everhart. "Sharks of Kansas". Oceans of Kansas. Archived from the original on 2018-09-02. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- Denton Lee O’Neal (2015). Chemostratigraphic and depositional characterization of the Niobrara Formation, Cemex Quarry, Lyons, CO (PDF) (Thesis). Colorado School of Mines. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-11-11. Retrieved 2018-11-10.

- Kenshu Shimada, Stephen L. Cumbaa, and Deanne van Rooyen (2006). "Caudal Fin Skeleton of the Late Cretaceous Lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli, from the Niobrara Chalk of Kansas". New Mexico Museum of Natural History Bulletin. 35: 185–191.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Humberto G. Ferron (2017). "Regional endothermy as a trigger for gigantism in some extinct macropredatory sharks". PLOS One. 12 (9): e0185185. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1285185F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185185. PMC 5609766. PMID 28938002.

- John K. Carlson, Kenneth J. Goldman, and Christopher G. Lowe. (2004). "Metabolism, Energetic Demand, and Endothermy" in Carrier, J.C., J.A. Musick and M.R. Heithaus. Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives. CRC Press. pp. 203–224. ISBN 978-0-8493-1514-5.

- Sun H. Kim, Kenshu Shimada, and Cynthia K. Rigsby (2013). "Anatomy and Evolution of Heterocercal Tail in Lamniform Sharks". The Anatomical Record. 296 (3): 433–442. doi:10.1002/ar.22647. PMID 23381874.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Bruce A. Wright (2007) Alaska's Great White Sharks. Top Predator Publishing Company. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-615-15595-1.

- Morten B. S. Svendsen; Paolo Domenici; Stefano Marras; Jens Krause; Kevin M. Boswell; Ivan Rodriguez-Pinto; Alexander D. M. Wilson; Ralf H. J. M. Kurvers; Paul E. Viblanc; Jean S. Finger; John F. Steffensen (2016). "Maximum swimming speeds of sailfish and three other large marine predatory fish species based on muscle contraction time and stride length: a myth revisited". Biology Open. 5 (10): 1415–1419. doi:10.1242/bio.019919. ISSN 2046-6390.

- Jayson M. Semmens; Alison A. Kock; Yuuki Y. Watanabe; Charles M. Shepard; Eric Berkenpas; Kilian M. Stehfest; Adam Barnett; Nicholas L. Payne (2019). "Preparing to launch: biologging reveals the dynamics of white shark breaching behaviour". Marine Biology. 166 (7). doi:10.1007/s00227-019-3542-0. ISSN 0025-3162.

- C. Díez, M. Soto, and J. M. Blanco (2015). "Biological characterization of the skin of shortfin mako shark Isurus oxyrinchus and preliminary study of the hydrodynamic behaviour through computational fluid dynamics". Journal of Fish Biology. 87 (1): 123–137. doi:10.1111/jfb.12705. PMID 26044174.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "PV OR 4498". Natural History Museum Specimen Collection. 2009-01-07. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- Anne Sørensen, Finn Surlyk, and Johan Lindgren (2013). "Food resources and habitat selection of a diverse vertebrate fauna from the upper lower Campanian of the Kristianstad Basin, southern Sweden". Cretaceous Research. 42: 85–92. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2013.02.002.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mike Everhart (2005). "Bite marks on an elasmosaur (Sauropterygia; Plesiosauria) paddle from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) as probable evidence of feeding by the lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli" (PDF). PalArch's Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 2 (2). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- Kenshu Shimada and G. E. Hooks (2004). "Shark-bitten protostegid turtles from the Upper Cretaceous Mooreville Chalk, Alabama". Journal of Paleontology. 78: 205–210. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2004)078<0205:SPTFTU>2.0.CO;2.

- Mike Everhart (1999). "Parts is parts and pieces is pieces". Oceans of Kansas. Archived from the original on 2018-06-26. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- Mark P. Witton (2018). "Pterosaurs in Mesozoic food webs: a review of fossil evidence". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 455 (1): 7–23. Bibcode:2018GSLSP.455....7W. doi:10.1144/SP455.3.

- David W.E. Hone, Mark P. Witton, and Michael B. Habib (2018). "Evidence for the Cretaceous shark Cretoxyrhina mantelli feeding on the pterosaur Pteranodon from the Niobrara Formation". PeerJ. 6 (e6031): e6031. doi:10.7717/peerj.6031. PMC 6296329. PMID 30581660.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mike Everhart and Keith Ewell (2006). "Shark-bitten dinosaur (Hadrosauridae) caudal vertebrae from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Coniacian) of western Kansas". Kansas Academy of Science. 109: 27–35. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2006)109[27:SDHCVF]2.0.CO;2.

- Mike J. Everhart and Shawn A. Hamm (2005). "A new nodosaur specimen (Dinosauria: Nodosauridae) from the Smoky Hill Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of western Kansas". Kansas Academy of Science. 108: 15–21. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2005)108[0015:ANNSDN]2.0.CO;2.

- Iyad S. Zalmout (2001). "A selachian fauna from the Late Cretaceous of Jordan". Yarmouk University.

- Andrew Retzler, Mark A. Wilson, and Yoav Avnib (2012). "Chondrichthyans from the Menuha Formation (Late Cretaceous: Santonian–Early Campanian) of the Makhtesh Ramon region, southern Israel". Cretaceous Research. 40: 81–89. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2012.05.009.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Stephen L. Cumbaa, Kenshu Shimada, and Todd D. Cook (2010). "Mid-Cenomanian vertebrate faunas of the Western Interior Seaway of North America and their evolutionary, paleobiogeographical, and paleoecological implications". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 295 (1–2): 199–214. Bibcode:2010PPP...295..199C. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.05.038.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mikael Siverson (2012). "Lamniform Sharks: 110 Million Years of Ocean Supremacy". YouTube (Podcast). Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- Alison M. Murray and Todd D. Cook (2016). "Overview of the Late Cretaceous fishes of the Northern Western Interior Seaway". Cretaceous Period: Biotic Diversity and Biogeography. 71: 255–261. Archived from the original on 2018-12-30. Retrieved 2018-12-30.

- Oliver Friedrich, Richard D. Norris, and Jochen Erbacher (2012). "Evolution of middle to Late Cretaceous oceans – A 55 m.y. record of Earth's temperature and carbon cycle". Geology. 40 (2): 107–110. Bibcode:2012Geo....40..107F. doi:10.1130/G32701.1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Nathalie Bardet, Alexandra Houssaye, Jean-Claude Rage, and Xabier Pereda Suberbiola (2008). "The Cenomanian-Turonian (late Cretaceous) radiation of marine squamates (Reptilia): the role of the Mediterranean Tethys". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 179 (6): 605–622. doi:10.2113/gssgfbull.179.6.605.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- In Brief (2008-06-16). "Submarine eruption bled Earth's oceans of oxygen". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 2014-01-06. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- L. Barry Albright III, David D. Gillette, and Alan L. Titus (2007). "Plesiosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian-Turonian) tropic shale of southern Utah, Part 1: New records of the pliosaur Brachauchenius lucasi". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27: 31–40. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[31:PFTUCC]2.0.CO;2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Elizabeth L. Nicholls and Anthony P. Russel (1990). "Paleobiogeography of the Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway of North America: the vertebrate evidence". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 79 (1–2): 149–169. Bibcode:1990PPP....79..149N. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(90)90110-S.

- Cretoxyrhina at fossilworks.org

- Boris Ekrt; Martin Košt'ák; Martin Mazuch; Silke Voigt; Frank Wiese (2008). "New records of teleosts from the Late Turonian (Late Cretaceous) of the Bohemian Cretaceous Basin (Czech Republic)". Cretaceous Research. 29 (4): 659–673. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2008.01.013.

- Mikael Siverson (1996). "Lamniform sharks of the Mid Cretaceous Alinga Formation and Beedagong Claystone, Western Australia" (PDF). Palaeontology. 39 (4): 813–849.

- Annie P. McIntosh; Kenshu Shimada; Michael J. Everhart (2016). "Late Cretaceous Marine Vertebrate Fauna from the Fairport Chalk Member of the Carlile Shale in Southern Ellis County, Kansas, U.S.A.". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 119 (2): 222–230. doi:10.1660/062.119.0214.

- Christopher Gallardo; Kenshu Shimada; Bruce A. Shumacher (2013). "A New Late Cretaceous Marine Vertebrate Assemblage from the Lincoln Limestone Member of the Greenhorn Limestone in Southeastern Colorado". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 115 (3–4): 107–116. doi:10.1660/062.115.0303.

- Nikita V. Zelenkov; Alexander O. Averianov; Evgeny V. Popov (2017). "An Ichthyornis-like bird from the earliest Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) of European Russia". Cretaceous Research. 75 (1): 94–100. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2017.03.011.

- Andrei V. Panteleyev; Evgenii V. Popov; Alexander O. Averianov (2004). "New record of Hesperornis rossicus (Aves, Hesperornithiformes) in the Campanian of Saratov Province, Russia". Paleontological Research. 8 (2): 115–122. doi:10.2517/prpsj.8.115.

- Akihiro Misaki; Hideo Kadota; Haruyoshi Maeda (2008). "Discovery of mid-Cretaceous ammonoids from the Aridagawa area, Wakayama, southwest Japan". Paleontological Research. 12 (1): 19–26. doi:10.2517/1342-8144(2008)12[19:DOMAFT]2.0.CO;2.

- Mikael Siverson and Marcin Machalski (2017). "Late late Albian (Early Cretaceous) shark teeth from Annopol, Pol". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 41 (4): 433–463. doi:10.1080/03115518.2017.1282981.

- Samuel Giersch; Eberhard Frey; Wolfgang Stinnesbeck; Arturo H. Gonzalez (2008). "Fossil fish assemblages of northeastern Mexico: New evidence of Mid Cretaceous Actinopterygian radiation" (PDF). 6th Meeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Paleontologists: 43–45.

- Naoshu Kitamura (2019). "Features and paleoecological significance of the shark fauna from the Upper Cretaceous Hinoshima Formation, Himenoura Group, Southwest Japan" (PDF). Paleontological Research. 23 (2): 110–130. doi:10.2517/2014PR020.

- Octávio MateusI; Louis L. Jacobs; Anne S. Schulp; Michael J. Polcyn; Tatiana S. Tavares; André Buta Neto; Maria Luísa Morais; Miguel T. Antunes (2011). "Angolatitan adamastor, a new sauropod dinosaur and the first record from Angola" (PDF). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 83 (1): 221–233. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652011000100012. PMID 21437383.

- Guillaume Guinot; Jorge D. Carrillo-Briceno (2017). "Lamniform sharks from the Cenomanian (Upper Cretaceous) of Venezuela" (PDF). Cretaceous Research. 82 (2018): 1–20. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2017.09.021.

- Oliver Hampe (2005). "Considerations on a Brachauchenius skeleton (Pliosauroidea) from the lower Paja Formation (late Barremian) of Villa de Leyva area (Colombia)". Institut Fur Palaontologie. 8: 37–51. doi:10.1002/mmng.200410003.

- Bruce A. Schumacher, Kenneth Carpenter, and Michael J. Everhart (2013). "A new Cretaceous Pliosaurid (Reptilia, Plesiosauria) from the Carlile Shale (middle Turonian) of Russell County, Kansas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (3): 613–628. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.722576.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kenshu Shimada and Tracy K. Ystesund (2007). "A dolichosaurid lizard, Coniasaurus cf. C. crassidens, from the Upper Cretaceous Carlile Shale in Russell County, Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 110 (3 & 4): 236–242. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2007)110[236:ADLCCC]2.0.CO;2.

- Boris Ekrt, Martin Košťák, Martin Mazuch, J. Valiceck (2001). "Short note on new records of late Turonian (Upper Cretaceous) marine reptile remains from the Upohlavy quarry (NW Bohemia, Czech Republic)". Bulletin of the Czech Geological Survey. 76 (2): 101–106.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Michael Everhart. "Rapid evolution, diversification and distribution of mosasaurs (Reptilia; Squamata) prior to the KT Boundary". Tate 2005 11th Annual Symposium in Paleontology and Geology.

- Corinne Myers and Bruce Lieberman (2010). "Sharks that pass in the night: using Geographical Information Systems to investigate competition in the Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 278 (1706): 681–689. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1617. PMC 3030853. PMID 20843852.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cretoxyrhina. |