Tylosaurus

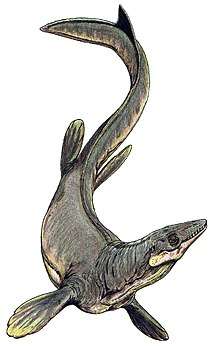

Tylosaurus (from the ancient Greek τυλος (tylos) "protuberance, knob" + Greek σαυρος (sauros) "lizard") was a mosasaur, a large, predatory marine reptile closely related to modern monitor lizards and to snakes, from the Late Cretaceous.

| Tylosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| "Bunker" T. proriger (KUVP 5033) mounted skeleton in the Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center in Woodland Park, Colorado | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Superfamily: | †Mosasauroidea |

| Family: | †Mosasauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Tylosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Tylosaurus Marsh, 1872 |

| Type species | |

| †Tylosaurus proriger Cope, 1869 | |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

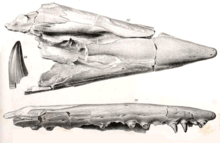

A distinguishing characteristic of Tylosaurus is its elongated, cylindrical premaxilla (snout) from which it takes its name. Unlike other mosasaurs, Tylosaurus did not have teeth all the way forward on its premaxilla, as the bony protuberance was free of teeth.[9] Tylosaurus also have 24 to 26 teeth in the upper jaw, 20 to 22 teeth on the palate, 26 teeth on the lower jaw, 29 to 30 vertebrate between the skull and hip, 6 to 7 vertebrae in the hip, 33 to 34 vertebrae in the tail with chevrons, and a further 56 to 58 vertebrae making up the tip of the tail.[8]

Early restorations showing Tylosaurus with a dorsal crest were based on misidentified tracheal cartilage, but when the error was discovered, depicting mosasaurs with such crests was already a trend.[10][11] Its skin had many small scales.

Size

Along with plesiosaurs, sharks, fish, and other mosasaurs, Tylosaurus was a dominant predator of the Western Interior Seaway during the Late Cretaceous. The genus was among the largest of the mosasaurs (along with Mosasaurus hoffmannii), with the possibly conspecific[8] Hainosaurus bernardi reaching lengths up to 12.2 meters (40 ft), and T. pembinensis reaching comparable sizes.[12] T. proriger, the largest species of Tylosaurus, reached lengths of about 14 m (46 ft).[13]

In late 2014 the Guinness World Records awarded the museum with a record for Largest Publicly Displayed Mosasaur - Bruce. The record was added to the 2016 print edition of the Guinness World Records.[14]

Discovery and naming

Like many other mosasaurs, the early history of this taxon is complex and involves the infamous rivalry between two early American paleontologists, Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh. Originally, the name "Macrosaurus" proriger was proposed by Cope for a fragmentary skull and thirteen vertebrae collected from near Monument Rocks in western Kansas in 1868.[15] It was placed in the collections of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. Only a year later, Cope redescribed the same material in greater detail and referred it, instead, to the English mosasaur taxon Liodon. Then, in 1872, Marsh named a more complete specimen as a new genus, Rhinosaurus ("nose lizard"), but soon discovered that this name had already been used for a different animal. Cope suggested that Rhinosaurus be replaced by yet another new name, Rhamposaurus which also proved to be preoccupied. Marsh finally erected Tylosaurus later in 1872, to include the original Harvard material as well as additional, more complete specimens which had also been collected from Kansas.[16] A giant specimen of T. proriger, recovered in 1911 by C. D. Bunker near Wallace, Kansas is one of the largest skeletons of Tylosaurus ever found. It is currently on display at the University of Kansas Museum of Natural history.

In 1918, Charles H. Sternberg found a Tylosaurus, with the remains of a plesiosaur in its stomach.[17] The specimen is currently on display in the Smithsonian, while the plesiosaur remains are stored in the collections. Although these important specimens were briefly reported by Sternberg in 1922 the find was largely overlooked until 2001. This specimen was rediscovered and described by Michael J. Everhart in 2004.[18] This find formed the basis for the story line in the 2007 National Geographic IMAX movie Sea Monsters: A Prehistoric Adventure, and a book Sea Monsters: Prehistoric Creatures of the Deep.[19]

A photograph of a Tylosaurus skull was taken by George F. Sternberg about 1926 after he collected and prepared the specimen. It was discovered in the Smoky Hill Chalk of Logan County, Kansas. Sternberg offered the specimen to the Smithsonian and included a photograph in his letter to Charles Gilmore. Copies of the original photos are in the archives of the Sternberg Museum of Natural History (FHSM). The specimen is FHSM VP-3, the exhibit specimen in the same museum.

A 34 feet (10 m) long Tylosaurus found in Kansas by Alan Komrosky in 2009 is now on display at the Museum of World Treasures in Wichita, Kansas.[20]

Tylosaurus has now been described from formations in Saskatchewan and South Dakota.[21]

Classification

Though many species of Tylosaurus have been named over the years, only a few are now recognized by scientists as taxonomically valid. They are as follows: Tylosaurus proriger (Cope, 1869[15]), from the Santonian and lower to middle Campanian of North America (Kansas, Alabama, Nebraska, etc.) and Tylosaurus nepaeolicus (Cope, 1874[22]), from the Santonian of North America (Kansas). Tylosaurus kansasensis, named by Everhart in 2005[23] from the late Coniacian of Kansas, has been shown to be based on juvenile specimens of T. nepaeolicus.[24] It is likely that T. proriger evolved as a paedomorphic variety of T. nepaeolicus, retaining juvenile features into adulthood and attaining much larger adult size.[24]

A closely related genus, Hainosaurus, is known from the Cretaceous of North America and Europe. Both Tylosaurus and Hainosaurus are members of the group Tylosaurinae[25] and are referred to informally as "tylosaurines" or "tylosaurs." Research published in 2016, however, indicates that Hainosaurus is likely congeneric with Tylosaurus.[8] Bell[26] placed the tylosaurines together with the plioplatecarpine mosasaurs (Platecarpus, Plioplatecarpus, etc.) in an informal monophyletic grouping which he called the "Russellosaurinae."

The cladogram is modified from a phylogenetic analysis by Jiménez-Huidobro & Caldwell (2019) using Tylosaurus species with sufficiently known material to model accurate relationships.[5]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Growth

Konishi and colleagues in 2018 assigned specimen FHSM VP-14845, a small juvenile with an estimated skull length of 30 centimeters (12 in), to Tylosaurus based on the proportions of the braincase and the arrangement of the teeth in the snout and on the palate. However, the specimen lacks the characteristic snout projection of other Tylosaurus, which is present in juveniles of T. nepaeolicus and T. proriger with skull lengths of 40–60 cm (16–24 in). This suggests that Tylosaurus acquired the snout projection rapidly at an early stage in life, and also suggests that it did not develop due to sexual selection. Konishi and colleagues suggested a function in ramming prey, as employed by the modern orca.[9]

Diet

Stomach contents associated with specimens of Tylosaurus proriger indicate that this mosasaur had a varied diet, including fish, sharks, smaller mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and flightless diving birds such as Hesperornis.[27][18]

The Talkeetna Mountains Hadrosaur was a hadrosaurid of indeterminate classification whose carcass appeared to have been deposited in a bathyal or outer shelf environment that later became Alaska's Matanuska Formation. Every element of its skeleton not found in a concretion bore many closely spaced oval conical depressions ranging in diameter from 2.12–5.81 millimeters (0.083–0.229 in) and 1.64–3.62 mm (0.065–0.143 in) deep. These depressions are probably bite marks. The depressions are not symmetrical enough for gastropod drill marks and are not shaped like sponge borings. None of the preserved fish fossils of the Matanuska Formation fit the size or geometry of the borings. The size and spacing and shape by contrast, however, closely resembles the teeth of Tylosaurus proriger. The apparent tooth marks are unlikely to have occurred before the carcass was washed out to sea since that would have punctured the body, preventing the buildup of bloating gases that allowed the carcass to drift out to sea in the first place. The distribution of bite marks corresponds inversely to the presence of flesh in the animal. For instance, lower limb bones sustained the most damage because there was the least amount of flesh shielding the bones at those locations. The concretions formed as the flesh chemically reacted to the seafloor on the largest parts of the animal where the scavenging mosasaur would be unable to fully wrap its jaws around the carcass. Bones pulled free from the carcass were buried in the mud and preserved in mudstone.[28]

References

- J. G. Ogg; L. A. Hinnov (2012). Cretaceous. The Geologic Time Scale 2012. pp. 793–853. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-59425-9.00027-5. ISBN 9780444594259.

- Abelaid Loera Flores (2013). "Occurrence of a tylosaurine mosasaur (Mosasauridae; Russellosaurina) from the Turonian of Chihuahua State, Mexico" (PDF). Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana. 65 (1): 99–107.

- J.W.M. Jagt; J. Lindgren; M. Machalski; A. Radwański (2005). "New records of the tylosaurine mosasaur Hainosaurus from the Campanian-Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) of central Poland". Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 84 (Special Issue 3): 303–306. doi:10.1017/S0016774600021077.

- J.J. Hornung; M. Reich (2015). "Tylosaurine mosasaurs (Squamata) from the Late Cretaceous of northern Germany". Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 94 (1): 55–71. doi:10.1017/njg.2014.31.

- Paulina Jiménez-Huidobro; Michael W. Caldwell (2019). "A New Hypothesis of the Phylogenetic Relationships of the Tylosaurinae (Squamata: Mosasauroidea)" (PDF). Frontiers in Earth Science. 7 (47). doi:10.3389/feart.2019.00047.

- Louis L. Jacobs; Octávio Mateus; Michael J. Polcyn; Anne S. Schulp; Miguel Telles Antunes; Maria Luísa Morais; Tatiana da Silva Tavares (2006). "The occurrence and geological setting of Cretaceous dinosaurs, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and turtles from Angola" (PDF). Paleontological Society of Korea. 22 (1): 91–110.

- Norbert Keutgen; Zbigniew Remin; John W.M. Jagt (2017). "The late Maastrichtian Belemnella kazimiroviensis group (Cephalopoda, Coleoidea) in the Middle Vistula valley (Poland) and the Maastricht area (the Netherlands, Belgium) – taxonomy and palaeobiological implications". Palaeontologia Electronica. 20.2.38A: 1–29. doi:10.26879/671.

- Paulina Jimenez-huidobro and Michael W. Caldwell (2016). "Reassessment and reassignment of the early Maastrichtian mosasaur Hainosaurus bernardi Dollo, 1885, to Tylosaurus Marsh, 1872". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Online edition (3): e1096275. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1096275.

- Konishi, Takuya; Jiménez-Huidobro, Paulina; Caldwell, Michael W. (2018). "The Smallest-Known Neonate Individual of Tylosaurus (Mosasauridae, Tylosaurinae) Sheds New Light on the Tylosaurine Rostrum and Heterochrony". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (5): 1–11. doi:10.1080/02724634.2018.1510835.

- "H.F. Osborn 1899". Oceans of Kansas. April 18, 2008. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- "Mosasaur Fringe". Oceans of Kansas. January 13, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- Lindgren, J. (2005). "The first record of Hainosaurus (Reptilia, Mosasauridae) from Sweden". Journal of Paleontology. 79 (6): 1157–1165. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2005)079[1157:TFROHR]2.0.CO;2.

- "Fact File: Tylosaurus Proriger from National Geographic". Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- "Largest mosasaur on display". Guinness World Records. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- Cope ED. 1869. [Remarks on Macrosaurus proriger.] Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 11(81): 123.

- Marsh OC. 1872. Note on Rhinosaurus. American Journal of Science 4 (20): 147.

- Sternberg, C. H. (1922). "Explorations of the Permian of Texas and the chalk of Kansas". Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions. 30 (1): 119–120. doi:10.2307/3624047. JSTOR 3624047.

- Everhart, Michael J. (2004). "Plesiosaurs as the Food of Mosasaurs; New Data on the Stomach Contents of a Tylosaurus proriger (Squamata; Mosasauridae) from the Niobrara Formation of Western Kansas". The Mosasaur. 7: 41–46.

- Everhart, Michael J. (2007). Sea Monsters : Prehistoric Creatures of the Deep. National Geographic. ISBN 978-1426200854.

- "Museum Of World Treasures". Worldtreasures.org. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- "[dinosaur] Tylosaurus saskatchewanensis (new species) + African araripemydid turtle Taquetochelys decorata". dml.cmnh.org. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- Cope ED. 1874. Review of the vertebrata of the Cretaceous period found west of the Mississippi River. U. S. Geological Survey of the Territories, Bulletin 1 (2): 3-48.

- Everhart, M.J. (2005). "Tylosaurus kansasensis, a new species of tylosaurine (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the Niobrara Chalk of western Kansas, USA". Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 84 (3): 231–240. doi:10.1017/S0016774600021016.

- Paulina Jiménez-Huidobro, Tiago R. Simões & Michael W. Caldwell. (2016). Re-characterization of Tylosaurus nepaeolicus (Cope, 1874) and Tylosaurus kansasensis Everhart, 2005: Ontogeny or sympatry? Cretaceous Research, doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.04.008

- Williston SW. 1898. Mosasaurs. The University Geological Survey of Kansas, Part V. 4: 81-347 (pls. 10-72).

- Bell GL. Jr. 1997. A phylogenetic revision of North American and Adriatic Mosasauroidea. pp. 293-332 In: Callaway J. M. and E. L Nicholls, (eds.), Ancient Marine Reptiles, Academic Press, 501 pages.

- Martin, J. E.; Bjork, P. R. (1987). Martin, J. E.; Ostrander, G. E. (eds.). "Gastric residues associated with a mosasaur from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) Pierre Shale in South Dakota". Papers in Vertebrate Paleontology in Honor of Morton Green : Dakoterra. 3: 68–72.

- Pasch, A. D.; May, K. C. (2001). "Taphonomy and paleoenvironment of a hadrosaur (Dinosauria) from the Matanuska Formation (Turonian) in South-Central Alaska". In Tanke, D.H.; Carpenter, K.; Skrepnick, M. W. (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press. pp. 219–236.

- Bell GL. Jr. 1997. Part IV: Mosasauridae - Introduction. pp. 281–292 In: Callaway J. M. and E. L Nicholls, (eds.), Ancient Marine Reptiles, Academic Press, 501 pages.

- Everhart MJ. 2001. Revisions to the biostratigraphy of the Mosasauridae (Squamata) in the Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Chalk (Late Cretaceous) of Kansas. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 104 (1-2): 56–75.

- Everhart MJ. 2005. Earliest record of the genus Tylosaurus (Squamata; Mosasauridae) from the Fort Hays Limestone (Lower Coniacian) of western Kansas. Transactions 108 (3/4): 149–155.

- Everhart MJ. 2005. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press, 322 pp.

- Kiernan CR. 2002. Stratigraphic distribution and habitat segregation of mosasaurs in the Upper Cretaceous of western and central Alabama, with an historical review of Alabama mosasaur discoveries. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22 (1): 91-103.

- Russell DA. 1967. Systematics and morphology of American mosasaurs (Reptilia, Sauria). Yale Univ. Bull. 23: 241 pp.

- Novas FE, Fernández M, Gasparini ZB, Lirio JM, Nuñez HJ, Puerta P. 2002. Lakumasaurus antarcticus, n. gen. et sp., a new mosasaur (Reptilia, Squamata) from the Upper Cretaceous of Antarctica. Ameghiniana 39 (2): 245–249.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tylosaurus. |