Clean Air Act of 1963

The Clean Air Act of 1963 (42 U.S.C. § 7401) is a United States federal law designed to control air pollution on a national level.[1] It is one of the United States' first and most influential modern environmental laws, and one of the most comprehensive air quality laws in the world.[2][3] As with many other major U.S. federal environmental statutes, it is administered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), in coordination with state, local, and tribal governments.[4] Its implementing regulations are codified at 40 C.F.R. Sub-chapter C, Parts 50–97.

.svg.png) | |

| Long title | An Act to improve, strengthen, and accelerate programs for the prevention and abatement of air pollution. |

|---|---|

| Acronyms (colloquial) | CAA |

| Nicknames | Clean Air Act of 1963 |

| Enacted by | the 88th United States Congress |

| Effective | December 17, 1963 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 88-206 |

| Statutes at Large | 77 Stat. 392 |

| Codification | |

| Titles amended | 42 U.S.C.: Public Health and Social Welfare |

| U.S.C. sections amended | 42 U.S.C. ch. 85, subch. I § 7401 et seq. |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| Motor Vehicle Air Pollution Control Act of 1965 (79 Stat. 992, Pub.L. 89–272) Air Quality Act of 1967 (81 Stat. 485, Pub.L. 90–148) Clean Air Act Extension of 1970 (84 Stat. 1676, Pub.L. 91–604) Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 (91 Stat. 685, Pub.L. 95–95) Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 (104 Stat. 2468, Pub.L. 101–549) | |

| United States Supreme Court cases | |

| Union Elec. Co. v. EPA, 427 U.S. 246 (1976) Chevron USA v. Natural Resources Defense Council, 467 U.S. 837 (1984) Whitman v. American Trucking Ass'ns, Inc., 531 U.S. 457 (2001) | |

The 1955 Air Pollution Control Act was the first U.S. federal legislation that pertained to air pollution; it also provided funds for federal government research of air pollution.[4] The first federal legislation to pertain to "controlling" air pollution was the Clean Air Act of 1963.[5] The 1963 act accomplished this by establishing a federal program within the U.S. Public Health Service and authorizing research into techniques for monitoring and controlling air pollution.[6]

It was first amended in 1965, by the Motor Vehicle Air Pollution Control Act, which authorized the federal government to set required standards for controlling the emission of pollutants from certain automobiles, beginning with the 1968 models. A second amendment, the Air Quality Act of 1967, enabled the federal government to increase its activities to investigate enforcing interstate air pollution transport, and, for the first time, to perform far-reaching ambient monitoring studies and stationary source inspections. The 1967 act also authorized expanded studies of air pollutant emission inventories, ambient monitoring techniques, and control techniques.[7] While only six states had air pollution programs in 1960, all 50 states had air pollution programs by 1970 due to the federal funding and legislation of the 1960s.[8] Amendments approved in 1970 greatly expanded the federal mandate, requiring comprehensive federal and state regulations for both stationary (industrial) pollution sources and mobile sources. It also significantly expanded federal enforcement. Also, EPA was established on December 2, 1970 in order to consolidate pertinent federal research, monitoring, standard-setting and enforcement activities into one agency with environmental protection as its primary mission.[9][10]

Further amendments were made in 1990 to address the problems of acid rain, ozone depletion, and toxic air pollution, and to establish a national permit program for stationary sources, and increased enforcement authority. The amendments also established new auto gasoline reformulation requirements, set Reid vapor pressure (RVP) standards to control Evaporative emissions from gasoline, and mandated new gasoline formulations sold from May to September in many states. Reviewing his tenure as EPA Administrator under President George H. W. Bush, William K. Reilly characterized passage of the 1990 amendments to the Clean Air Act as his most notable accomplishment.[11]

The Clean Air Act was the first major environmental law in the United States to include a provision for citizen suits. Numerous state and local governments have enacted similar legislation, either implementing federal programs or filling in locally important gaps in federal programs.

Summary

.svg.png)

Title I: Programs and Activities

Part A: Air Quality and Emissions Limitations

This section of the act declares that protecting and enhancing the nation's air quality promotes public health. The law encourages to prevent regional air pollution and control programs. It also provides technical and financial assistance for preventing air pollution at both state and local governments. Additional sub chapters cover cooperation, research, investigation, training, and other activities. Grants for air pollution planning and control programs, and interstate air quality agencies and program cost limitations are also included in this section.[12]

The act mandates air quality control regions, designated as attainment vs non-attainment. Non-attainment areas do not meet national standards for primary or secondary ambient air quality. Attainment areas meet these standards, while unclassified areas cannot be classified based on the available information.[12]

Air quality criteria, national primary and secondary ambient air quality standards, state implementation plans and performance standards for new stationary sources are covered in Part A as well. The list of hazardous air pollutants that the act establishes includes compounds of Acetaldehyde, benzene, chloroform, Phenol, and selenium. The list also includes mineral fiber emissions from manufacturing or processing glass, rock or slag fibers as well as radioactive atoms. The list can periodically be modified. The act lists unregulated radioactive pollutants such as cadmium, arsenic, and poly cyclic organic matter and it mandates listing them if they will cause or contribute to air pollution that endangers public health, under section 7408 or 7412.[12]

The remaining sub-chapters cover smokestack heights, state plan adequacy, and estimating emissions of carbon monoxide, volatile organic compounds, and oxides of nitrogen from area and mobile sources. Measures to prevent unemployment or other economic disruption include using local coal or coal derivatives to comply with implementation requirements. The final sub chapter in this act focuses on land use authority.[12]

Part B: Ozone Protection

Because of advances in the atmospheric chemistry, this section was replaced by Title VI when the law was amended in 1990.[13]

This change in the law reflected significant changes in scientific understanding of ozone formation and depletion. Ozone absorbs UVC light and shorter wave UVB, and lets through UVA, which is largely harmless to people. Ozone exists naturally in the stratosphere, not the troposphere. It is laterally distributed because it is destroyed by strong sunlight, so there is more ozone at the poles. Ozone is created when O2 comes in contact with photons from solar radiation. Therefore, a decrease in the intensity of solar radiation also results in a decrease in the formation of ozone in the stratosphere. This exchange is known as the Chapman mechanism:

- O2 + UV photon → 2 O (note that atmospheric oxygen as O is highly unstable)

- O + O2 + M → O3 (O3 is Ozone) + M

- M represents a third molecule, needed to carry off the excess energy of the collision of O + O2.

Atmospheric freon and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) contribute to ozone depletion (Chlorine is a catalytic agent in ozone destruction). Following discovery of the ozone hole in 1985, the 1987 Montreal Protocol successfully implemented a plan to replace CFCs and was viewed by some environmentalists as an example of what is possible for the future of environmental issues, if the political will is present.

Part C : Prevention of Significant Deterioration of Air Quality

The Clean Air Act requires permits to build or add to major stationary sources of air pollution. This permitting process, known as New Source Review (NSR), applies to sources in areas that meet air quality standards as well as areas that are unclassified.[14] Permits in attainment or unclassified areas are referred to as Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) permits, while permits for sources located in nonattainment areas are referred to as non attainment area (NAA) permits.[15]

The fundamental goals of the PSD program are to:

- prevent new non-attainment areas by ensuring economic growth in harmony with existing clean air;

- protect public health and welfare from any adverse effects;

- preserve and enhance the air quality in national parks and other areas of special natural recreational, scenic, or historic value.[15]:3

Part D: Plan Requirements for Non-attainment Areas

Under the Clean Air Act states are required to submit a plan for non-attainment areas to reach attainment status as soon as possible but in no more than five years, based on the severity of the air pollution and the difficulty posed by obtaining cleaner air.

The plan must include:

- an inventory of all pollutants

- permits

- control measures, means and techniques to reach standard qualifications

- contingency measures

The plan must be approved or revised if required for approval, and specify whether local governments or the state will implement and enforce the various changes. Achieving attainment status makes a request for reevaluation possible. It must include a plan for maintenance of air quality.

Title II: Emission Standards for Moving Sources

Part A: Motor Vehicle Emission and Fuel Standards

Sub-chapters of Title II cover state standards and grants, prohibited acts and actions to restrain violations, as well as a study of emissions from non road vehicles (other than locomotives) to determine whether they cause or contribute to air pollution. Motorcycles are treated in the same way as automobiles under the emission standards for new motor vehicles or motor vehicle engines. The last few sub chapters deal with high altitude performance adjustments, motor vehicle compliance program fees, prohibition on production of engines requiring leaded gasoline and urban bus standards.[16]

This part of the bill was extremely controversial the time it was passed. The automobile industry argued that it could not meet the new standards.[8] Senators expressed concern about impact on the economy. However the stricter standards led to the creation of the catalytic converter, which was a revolutionary development. (Coincidentally, these converters didn't work well with leaded gas, which contributed to the swift removal of lead from gasoline that was also recognized for having adverse health effects.)[8] Specific new emissions standards for moving sources passed years later.

Part B: Aircraft Emission Standards

Many volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are emitted over airports and affect the air quality in the region. VOCs include benzene, formaldehyde and butadienes which are known to cause health problems such as birth defects, cancer and skin irritation. Hundreds of tons of emissions from aircraft, ground support equipment, heating systems, and shuttles and passenger vehicles are released into the air, causing smog. Therefore, major cities such as Seattle, Denver, and San Francisco require a Climate Action Plan as well as a greenhouse gas inventory. Additionally, federal programs such as the Voluntary Airport Low Emissions Program (VALE) are working to offset costs for programs that reduce emissions.[17]

Title II sets emission standards for airlines and aircraft engines and adopts standards set by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). However aircraft carbon dioxide emission standards have not been established by either ICAO nor the EPA.[18] It is the responsibility of the Secretary of Transportation, after consultation with the Administrator, to prescribe regulations that comply with 42 U.S. Code § 7571 (Establishment of standards) and ensure the necessary inspections take place.[19]

Part C: Clean Fuel Vehicles

Trucks and automobiles play a large role in deleterious air quality. Harmful chemicals such as nitrogen oxide, hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide are released from motor vehicles. Some of these also react with sunlight to produce Photochemical.[20] These harmful substances change the climate, alter ocean pH and include toxins that may cause cancer, birth defects or respiratory illness. Motor vehicles increased in the 1990s since approximately 58 percent of households owned two or more vehicles.[20] The Clean Fuel Vehicle programs focused on alternative fuel use and petroleum fuels that met low emission vehicle (LEV) levels. Compressed natural gas, ethanol,[21] methanol,[22] liquefied petroleum gas and electricity are examples of cleaner alternative fuel. Programs such as the California Clean Fuels Program and pilot program are increasing demand that for new fuels to be developed to reduce harmful emissions.[20]

The California pilot program incorporated under this section focuses on pollution control in ozone non-attainment areas. The provisions apply to light-duty trucks and light-duty vehicles in California. The state also requires that clean alternative fuels for sale at numerous locations with sufficient geographic distribution for convenience. Production of clean-fuel vehicles isn't mandated except as part of the California pilot program.[12]

Title III: General Provisions

Under the law prior to 1990, EPA was required to construct a list of Hazardous Air Pollutants as well as health-based standards for each one. There were 187 air pollutants listed and the source from which they came. The EPA was given ten years to generate technology-based emission standards. Title III is considered a second phase, allowing the EPA to assess lingering risks after the enactment of the first phase of emission standards. Title III also enacts new standards with regard to the protection of public health.[23]

A citizen may file a lawsuit to obtain compliance with an emission standard issued by the EPA or by a state, unless there is an ongoing enforcement action being pursued by EPA or the appropriate state agency.[24]

Title IV: Noise Pollution

This title pre-dates the Clean Air Act. With the passage of the Clean Air Act, it became codified as Title IV. However, another Title IV was enacted in the 1990 amendments. The second Title IV was then appended to this Title IV as Title IV-A (see below).

This title established the EPA Office of Noise Abatement and Control to reduce noise pollution in urban areas, to minimize noise-related impacts on psychological and physiological effects on humans, effects on wildlife and property (including values), and other noise-related issues. The agency was also assigned to run experiments to study the effects of noise.

Title IV-A: Acid Deposition Control

This title was added as part of the 1990 amendments. It addresses the issue of acid rain, which is caused by nitrogen oxides (NO

x ) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions from electric power plants powered by fossil fuels, and other industrial sources. The 1990 amendments gave industries more pollution control options including switching to low-sulfur coal and/or adding devices that controlled the harmful emissions. In some cases plants had to be closed down to prevent the dangerous chemicals from entering the atmosphere.[25]

Title IV-A mandated a two-step process to reduce SO2 emissions. The first stage required more than 100 electric generating facilities larger than 100 megawatts to meet a 3.5 million ton SO2 emission reduction by January 1995. The second stage gave facilities larger than 75 megawatts a January 2000 deadline.[26]

Title V: Permits

The 1990 amendments authorized a national operating permit program, covering thousands of large industrial and commercial sources.[27] It required large businesses to address pollutants released into the air, measure their quantity, and have a plan to control and minimize them as well as to periodically report. This consolidated requirements for a facility into a single document.[27]

In non-attainment areas, permits were required for sources that emit as little as 50, 25, or 10 tons per year of VOCs depending on the severity of the region's non-attainment status.[28]

Most permits are issued by state and local agencies.[29] If the state does not adequately monitor requirements, the EPA may take control. The public may request to view the permits by contacting the EPA. The permit is limited to no more than five years and requires a renewal.[28]

Title VI: Stratospheric Ozone Protection

Starting in 1990, Title VI mandated regulations regarding the use and production of chemicals that harm the Earth's stratospheric ozone layer. This ozone layer protects against harmful ultraviolet B sunlight linked to several medical conditions including cataracts and skin cancer.[30]

The ozone-destroying chemicals were classified into two groups, Class I and Class II. Class I consists of substances, including chlorofluorocarbons, that have an ozone depletion potential (ODP) (HL) of 0.2 or higher. Class II lists substances, including hydro chlorofluorocarbons, that are known to or may be detrimental to the stratosphere. Both groups have a timeline for phase-out:

- For Class I substances, no more than seven years after being added to the list and

- For Class II substances no more than ten years.[25]

Title VI establishes methods for preventing harmful chemicals from entering the stratosphere in the first place, including recycling or proper disposal of chemicals and finding substitutes that cause less or no damage.[25] The Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP) Program is EPA's program to evaluate and regulate substitutes for the ozone-depleting chemicals that are being phased out under the stratospheric ozone protection provisions of the Clean Air Act.[31]

Over 190 countries signed the Montreal Protocol in 1987, agreeing to work to eliminate or limit the use of chemicals with ozone-destroying properties.[30]

History

Legislation

Congress passed the first legislation to address air pollution with the 1955 Air Pollution Control Act that provided funds to the U.S. Public Health service, but did not formulate pollution regulation.[32] However, the Clean Air Act in 1963 created a research and regulatory program in the U.S. Public Health Service.[33] The Act authorized development of emission standards for stationary sources, but not mobile sources of air pollution.[34]:211 The 1967 Air Quality Act mandated enforcement of interstate air pollution standards and authorized ambient monitoring studies and stationary source inspections.[35]

In the Clean Air Act Extension of 1970, Congress greatly expanded the federal mandate by requiring comprehensive federal and state regulations for both industrial and mobile sources.[36] The law established four new regulatory programs:

- National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). EPA was required to promulgate national standards for six criteria pollutants: carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, particulate matter, hydrocarbons and photochemical oxidants. (Some of the criteria pollutants were revised in subsequent legislation.)[34]:213[37]

- State Implementation Plans (SIPs)

- New Source Performance Standards (NSPS); and

- National Emissions Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAPs).

The 1970 law is sometimes called the "Muskie Act" because of the central role Maine Senator Edmund Muskie played in drafting the bill.[38]

To implement the strict new Clean Air Act of 1970, during his first term as EPA Administrator William Ruckelshaus spent 60% of his time on the automobile industry, whose emissions were to be reduced 90% under the new law. Senators had been frustrated at the industry's failure to cut emissions under previous, weaker air laws.[39]

The Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 required Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) of air quality for areas attaining the NAAQS and added requirements for non-attainment areas.[40]

The 1990 Clean Air Act added regulatory programs for control of acid deposition (acid rain) and stationary source operating permits. The provisions aimed at reducing sulfur dioxide emissions included a cap-and-trade program, which gave power companies more flexibility in meeting the law's goals compared to earlier iterations of the Clean Air Act.[41] The amendments moved considerably beyond the original criteria pollutants, expanding the NESHAP program with a list of 189 hazardous air pollutants to be controlled within hundreds of source categories, according to a specific schedule.[42] The NAAQS program was also expanded. Other new provisions covered stratospheric ozone protection, increased enforcement authority and expanded research programs.[43]

History of the Clean Air Act

Introduction

The legal authority for federal programs regarding air pollution control is based on the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments (1990 CAAA). These are the latest in a series of amendments made to the Clean Air Act (CAA), often referred to as "the Act." This legislation modified and extended federal legal authority provided by the earlier Clean Air Acts of 1963 and 1970.[7]

The 1955 Air Pollution Control Act was the first federal legislation involving air pollution; it authorized $3 million per year to the U.S. Public Health Service for five years to fund federal level air pollution research, air pollution control research, and technical and training assistance to the states. Subsequently, the act was extended for four years in 1959 with funding levels at $5 million per year. The act was then amended in 1960 and 1962. Although the 1955 act brought the air pollution issue to the federal level, no federal regulations were formulated. Control and prevention of air pollution was instead delegated to state and local agencies.[32]

The Clean Air Act of 1963 was the first federal legislation regarding air pollution control. It established a federal program within the U.S. Public Health Service and authorized research into techniques for monitoring and controlling air pollution. In 1967, the Air Quality Act was enacted in order to expand federal government activities. In accordance with this law, enforcement proceedings were initiated in areas subject to interstate air pollution transport. As part of these proceedings, the federal government for the first time conducted extensive ambient monitoring studies and stationary source inspections.

The Air Quality Act of 1967 also authorized expanded studies of air pollutant emission inventories, ambient monitoring techniques, and control techniques.[7]

Clean Air Amendments of 1970

The Clean Air Amendments of 1970 (1970 CAA) authorized the development of comprehensive federal and state regulations to limit emissions from both stationary (industrial) sources and mobile sources.[44] Four major regulatory programs affecting stationary sources were initiated:

- the National Ambient Air Quality Standards [NAAQS (pronounced "knacks")],

- State Implementation Plans (SIPs),

- New Source Performance Standards (NSPS),

- and National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAPs).

Enforcement authority was substantially expanded. These major amendments were adopted during the same year as the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act and the establishment of EPA.[7][10]

Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977

Major amendments were added to the Clean Air Act in 1977 (1977 CAAA). The 1977 Amendments primarily concerned provisions for the Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) of air quality in areas attaining the NAAQS. The 1977 CAAA also contained requirements pertaining to sources in non-attainment areas for NAAQS. A non-attainment area is a geographic area that does not meet one or more of the federal air quality standards. Both of these 1977 CAAA established major permit review requirements to ensure attainment and maintenance of the NAAQS.[7] These amendments also included the adoption of an offset trading policy originally applied to Los Angeles in 1974 that enables new sources to offset their emissions by purchasing extra reductions from existing sources.[8]

Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990

Another set of major amendments to the Clean Air Act occurred in 1990 (1990 CAAA). The 1990 CAAA substantially increased the authority and responsibility of the federal government. New regulatory programs were authorized for control of acid deposition (acid rain)[45] and for the issuance of stationary source operating permits. The NESHAPs were incorporated into a greatly expanded program for controlling toxic air pollutants. The provisions for attainment and maintenance of NAAQS were substantially modified and expanded. Other revisions included provisions regarding stratospheric ozone protection, increased enforcement authority, and expanded research programs.[7]

Milestones

Some of the principal milestones in the evolution of the Clean Air Act are as follows:[7]

The Air Pollution Control Act of 1955

- First federal air pollution legislation

- Funded research on scope and sources of air pollution

Clean Air Act of 1963

- Authorized a national program to address air pollution

- Authorized research into techniques to minimize air pollution

Air Quality Act of 1967

- Authorized enforcement procedures involving interstate transport of pollutants

- Expanded research activities

Clean Air Act of 1970

- Established National Ambient Air Quality Standards

- Established requirements for State Implementation Plans to achieve them

- Establishment of New Source Performance Standards for new and modified stationary sources

- Establishment of National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants

- Increased enforcement authority

- Authorized control of motor vehicle emissions

1977 Amendments to the Clean Air Act of 1970

- Authorized provisions related to prevention of significant deterioration

- Authorized provisions relating to non-attainment areas

1990 Amendments to the Clean Air Act of 1970

- Authorized programs for acid deposition control

- Authorized controls for 189 toxic pollutants, including those previously regulated by the national emission standards for hazardous air pollutants

- Established permit program requirements

- Expanded and modified provisions concerning National Ambient Air Quality Standards

- Expanded and modified enforcement authority

Regulations

Since the initial establishment of six mandated criteria pollutants (ozone, particulate matter, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, and lead), advancements in testing and monitoring have led to the discovery of many other significant air pollutants.[46]

However, with the act in place and its many improvements, the U.S. has seen many pollutant levels and associated cases of health complications drop. According to the EPA, the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments has prevented or will prevent:

| Year 2010 (cases prevented) | Year 2020 (cases prevented) | |

|---|---|---|

| Adult Mortality - particles | 160,000 | 230,000 |

| Infant Mortality - particles | 230 | 280 |

| Mortality - ozone | 4,300 | 71,000 |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 54,000 | 75,000 |

| Heart Disease - Acute Myocardial Infarction | 130,000 | 200,000 |

| Asthma Exacerbation | 1,700,000 | 2,400,000 |

| Emergency Room Visits | 86,000 | 120,000 |

| School Loss Days | 3,200,000 | 5,400,000 |

| Lost Work Days | 13,000,000 | 17,000,000 |

This chart shows the health benefits of the Clean Air Act programs that reduce levels of fine particles and ozone.[47]

In 1997 EPA tightened the NAAQS regarding permissible levels of the ground-level ozone that make up smog and the fine airborne particulate matter that makes up soot.[48][49] The decision came after months of public review of the proposed new standards, as well as long and fierce internal discussion within the Clinton administration, leading to the most divisive environmental debate of that decade.[50] The new regulations were challenged in the courts by industry groups as a violation of the U.S. Constitution's nondelegation principle and eventually landed in the Supreme Court of the United States,[49] whose 2001 unanimous ruling in Whitman v. American Trucking Ass'ns, Inc. largely upheld EPA's actions.[51]

The Clean Air Act (CAA or Act) directs the EPA to establish national ambient air quality standards (NAAQS) for pollutants at levels that will protect public health. The EPA and the American Lung Association promoted the 2011 Cross State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR) as a means of controlling ozone and fine particle emissions. It was claimed that this prevented up 400,000 asthma cases and saved two millions workdays and schooldays that otherwise would have been lost to respiratory illnesses. Cities and power companies sued the EPA over the law in EPA v. EME Homer City Generation, but the case was eventually decided in favor of the EPA.[52]

Roles of the federal government and states

The 1970 Clean Air Act required states to develop State Implementation Plans for how they would meet new national ambient air quality standards by 1977.[53] Although the 1990 Clean Air Act is a federal law covering the entire country, the states do much of the work to carry out the Act. The EPA has allowed the individual states to elect responsibility for compliance with and regulation of the CAA within their own borders in exchange for funding. For example, a state air pollution agency holds a hearing on a permit application by a power or chemical plant or fines a company for violating air pollution limits. However, election is not mandatory and in some cases states have chosen to not accept responsibility for enforcement of the act and force the EPA to assume those duties.

In order to take over compliance with the CAA the states must write and submit a state implementation plan (SIP) to the EPA for approval. A state implementation plan is a collection of the regulations a state will use to clean up polluted areas. The states are obligated to notify the public of these plans, through hearings that offer opportunities to comment, in the development of each state implementation plan. The SIP becomes the state's legal guide for local enforcement of the CAA. For example, Rhode Island law requires compliance with the Federal CAA through the SIP.[54] The SIP delegates permitting and enforcement responsibility to the state Department of Environmental Management (RI-DEM).

The federal law recognizes that states should lead in carrying out the Clean Air Act, because pollution control problems often require special understanding of local industries, geography, housing patterns, etc. However, states are not allowed to have weaker pollution controls than the national minimum criteria set by EPA. EPA must approve each SIP, and if a SIP isn't acceptable, EPA can retain CAA enforcement in that state. For example, California was unable to meet the new standards set by the Clean Air Act of 1970, which led to a lawsuit and a federal state implementation plan for the state.[55]

The United States government, through the EPA, assists the states by providing scientific research, expert studies, engineering designs, and money to support clean air programs.

Metropolitan planning organizations must approve all federally funded transportation projects in a given urban area. If the MPO's plans do not, Federal Highway Administration and the Federal Transit Administration have the authority to withhold funds if the plans do not conform with federal requirements, including air quality standards.[56] In 2010, the EPA directly fined the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District $29 million for failure to meet ozone standards, resulting in fees for county drivers and businesses. This was the results of a federal appeals court case that required the EPA to continue enforce older, stronger standards,[57] and spurred debate in Congress over amending the Act.[58]

The law prevents states from setting standards that are more strict than the federal standards, but carves out a special exemption for California due to its past issues with smog pollution in the metropolitan areas. In practice, when California's environmental agencies decide on new vehicle emission standards, they are submitted to the EPA for approval under this waiver, with the most recent approval in 2009.[59] The California standard was adopted by twelve other states, and established the de facto standard that automobile manufacturers subsequently accepted, to avoid having to develop different emission systems in their vehicles for different states. However, in September 2019, President Donald Trump revoked this waiver, arguing that the stricter emissions have made cars too expensive, and by removing them, will make vehicles safer. EPA's Andrew Wheeler also stated that while the agency respects federalism, they could not allow one state to dictate standards for the entire nation. California's governor Gavin Newsom considered the move part of Trump's "political vendetta" against California and stated his intent to sue the federal government.[60] Twenty-three states, along with the District of Columbia and the cities of New York City and Los Angeles joined California in a federal lawsuit challenging the administration's decision.[61]

State programs

Many states, or concerned citizens of the state, have established their own programs to help promote pollution clean-up strategies.

For example, (in alphabetical order by state)

- California – California's Clean Air Project – designed to create a smoke-free gaming atmosphere in tribal casinos

- Georgia – The Clean Air Campaign

- Illinois – Illinois Citizens for Clean Air and Water – coalition of farmers and other citizens to reduce harmful effects of large-scale livestock production methods

- New York – Clean Air NY

- Oklahoma – "Breathe Easy" – Oklahoma Statutes on Smoking in Public Places and Indoor Workplaces (Effective November 1, 2010)[62]

- Oregon – Indoor Clean Air Act – Statutes on Smoking in Indoor Workplaces and Within 10 ft of an Entrance[63]

- Texas – Drive Clean Across Texas

- Virginia – Virginia Clean Cities, Inc.

Interstate air pollution

Air pollution often travels from its source in one state to another state. In many metropolitan areas, people live in one state and work or shop in another; air pollution from cars and trucks may spread throughout the interstate area. The 1990 Clean Air Act provides for interstate commissions on air pollution control, which are to develop regional strategies for cleaning up air pollution. The 1990 amendments include other provisions to reduce interstate air pollution.

The Acid Rain Program, created under Title IV of the Act, authorizes emissions trading to reduce the overall cost of controlling emissions of sulfur dioxide.

Leak detection and repair

The Act requires industrial facilities to implement a Leak Detection and Repair (LDAR) program to monitor and audit a facility's fugitive emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOC). The program is intended to identify and repair components such as valves, pumps, compressors, flanges, connectors and other components that may be leaking. These components are the main source of the fugitive VOC emissions.

Testing is done manually using a portable vapor analyzer that read in parts per million (ppm). Monitoring frequency, and the leak threshold, is determined by various factors such as the type of component being tested and the chemical running through the line. Moving components such as pumps and agitators are monitored more frequently than non-moving components such as flanges and screwed connectors. The regulations require that when a leak is detected the component be repaired within a set number of days. Most facilities get 5 days for an initial repair attempt with no more than 15 days for a complete repair. Allowances for delaying the repairs beyond the allowed time are made for some components where repairing the component requires shutting process equipment down.

Application to greenhouse gas emissions

EPA began regulating greenhouse gases (GHGs) from mobile and stationary sources of air pollution under the Clean Air Act for the first time on January 2, 2011, after having established its first auto emissions standards in 2010.[64] Standards for mobile sources have been established pursuant to Section 202 of the CAA, and GHGs from stationary sources are controlled under the authority of Part C of Title I of the Act. The EPA's auto emission standards for greenhouse gas emissions issued in 2010 and 2012 are intended to cut emissions from targeted vehicles by half, double fuel economy of passenger cars and light-duty trucks by 2025 and save over $4 billion barrels of oil and $1.7 trillion for consumers. The agency has also proposed a two-phase program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions for medium and heavy duty trucks and buses.[8]

Below is a table for the sources of greenhouse gases, taken from data in 2008.[65] Of all greenhouse gases, about 76 percent of the sources are manageable under the CAA, marked with an asterisk (*). All others are regulated independently, if at all.

| Source | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Electric Generation* | 34% |

| Industry* | 15% |

| Large Non-Agricultural Methane Sources* | 5% |

| Light-, Medium-, and Heavy-Duty Vehicles* | 22% |

| Other Transport | 7% |

| Commercial and Residential Heating | 7% |

| Agriculture | 7% |

| HFCs | 2% |

| Other | 1% |

Clean Air Act and environmental justice

By promoting pollution reduction, the Clean Air Act can help reduce heightened exposure to air pollution among communities of color and low-income communities.[66] Environmental researcher Dr. Marie Lynn Miranda notes that African American populations are "consistently over represented" in areas with the poorest air quality.[67] Dense populations of low-income and minority communities inhabit the most polluted areas across the United States, which is considered to exacerbate health problems among these populations.[68] High levels of exposure to air pollution is linked to several health conditions, including asthma, cancer, premature death, and infant mortality, each of which disproportionately impact communities of color and low-income communities.[69] The pollution reduction achieved by the Clean Air Act is associated with a decline in each of these conditions and can promote environmental justice for communities that are disproportionately impacted by air pollution and diminished health status.[69]

Clean Air Act violations

The EPA analyzes violators of the Clean Air Act and addresses the violators accordingly. For companies or parties that do not comply with the act monetary penalties can be cited. Per day the EPA could fine civil administrators $37,500 per day, with a maximum of about 8 days; unless otherwise mandated by the EPA. For a field citation which is against federal facilities which are not abiding by EPA standards can get fines up to $7,500 per day.[70]

Major cases of Clean Air Act violations include:

- The Volkswagen emissions scandal (2015), etc.

- Caterpillar and five other manufacturers violated diesel engine emission standards (consent decree, July 1999)[71]

- Alleged violations by Hyundai and Kia which resulted in a total $100 million in civil penalties paid to the United States and to the California Air Resources Board.[72]

Effects

A 2017 study found that the Clean Air Act of 1970 led to an over 10 percent reduction in pollution ("ambient TSP levels") in counties that exceeded the pollution thresholds set by the Act in the three years after the regulation went into effect. The study found that this regulation-induced reduction in air pollution has caused affected workers to work more and earned one percent more in annual earnings. The authors estimate that cumulative lifetime income gain for each affected individual is approximately $4,300 in present value terms.[73]

In addition, because air quality across the United States improved; it is estimated 205,000 premature deaths and millions of other respiratory complications were prevented which resulted in an economic savings of $50 trillion versus the $523 billion invested to meet the Clean Air Act standard.[74]

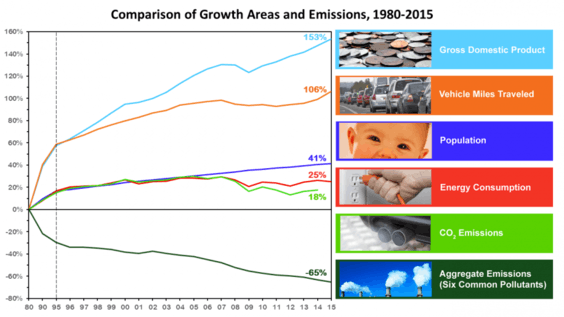

Mobile sources including automobiles, trains, and boat engines have become 99% cleaner for pollutants like hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and particle emissions since the 1970s. The allowable emissions of volatile organic chemicals, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and lead from individual cars have also been reduced by more than 90%, resulting in decreased national emissions of these pollutants despite a more than 400% increase in total miles driven yearly.[8]

Since the 1980s, 1/4th of ground level ozone has been cut, mercury emissions have been cut by 80%, and since the change from leaded gas to unleaded gas 90% of atmospheric lead pollution has been reduced.[75]

A 2018 study found that the Clean Air Act contributed to the 60% decline in pollution emissions by the manufacturing industry between 1990 and 2008.[76][77]

Future challenges

Climate change poses a challenge to the management of conventional air pollutants in the United States due to warmer, dryer summer conditions that can lead to increased air stagnation episodes. Prolonged droughts that may contribute to wildfires would also result in regionally high levels of air particles.[78]

As of 2017, some US cities still don't meet all national ambient air quality standards. It is likely that tens of thousands of premature deaths are still being caused by fine-particle pollution and ground-level ozone pollution.[8]

Air pollution is not bound to a nation. Often, air coming into the U.S. contains pollution from upwind countries, making it harder to meet air quality standards. In turn, air that travels downwind of the U.S. likely has pollutants in it already. Addressing this may require international negotiations of reductions of pollutants in the originating countries.[8] This also relates to the challenge of climate change.

Criticism

Diane Katz, a research fellow for the Heritage Foundation, criticized the validity of the Clean Air Act by stating, "The largest proportion of economic benefit is based on the value of avoiding premature mortality. Yet the valuation of this benefit ranks among the most significant uncertainties in the study, according to the researchers. Alternative estimates they cite would lower the benefit calculation by up to 22 percent."[79] The Clean Air Act is a constant battle between current economic benefits versus future cost benefits of both health of the nation, and economy.

See also

- Clean Air Act (disambiguation)

- Air quality law

- United States environmental law

- Alan Carlin, controversy over the EPA carbon dioxide endangerment finding

- Commission on Risk Assessment and Risk Management

- Emission standard

- Emissions trading

- Environmental policy of the United States

- Photochemical Assessment Monitoring Station

- Startups, shutdowns, and malfunctions

- The Center for Clean Air Policy (in the US)

- Regional Haze Rule

References

- "The Plain English Guide to the Clean Air Act". Clean Air Act Overview. Washington, D.C.: US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). April 2007.

- "Environmental Laws and Treaties". Natural Resources Defense Council. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- Gordon, Erin L. "History of the Modern Environmental Movement in America" (PDF).

- "Summary of the Clean Air Act". EPA. February 22, 2013. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- Shekhtman, Lonnie. "Beijing smog: What makes some cities cleaner than others?". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- Yang, Ming. Energy Efficiency: Benefits for Environment and Society.

-

- John Bachmann, David Calkins, Margo Oge. "Cleaning the Air We Breathe: A Half Century of Progress." EPA Alumni Association. September 2017.

-

- Rinde, Meir (2017). "Richard Nixon and the Rise of American Environmentalism". Distillations. 3 (1): 16–29. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- EPA Alumni Association: EPA Administrator William K. Reilly describes why passage of the 1990 Clean Air Act amendments was vitally important. Reflections on US Environmental Policy: An Interview with William K. Reilly Video, Transcript (see p10).

- "Clean Air Act: Title I - Air Pollution Prevention and Control". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Archived from the original on May 1, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- EPA. "Clean Air Act: Title VI - Stratospheric Ozone Protection." Archived November 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Updated December 19, 2008.

- "The Clean Air Act in a Nutshell: How It Works" (PDF). February 27, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

Collectively, the PSD permitting program and nonattainment area permitting program for major sources are known as "New Source Review." Before starting the construction of a new major source located in an attainment, or unclassifiable area, or the modification of an existing major source that results in a significant emissions increase in such areas, the source must obtain a PSD permit under the Act.

- EPA (1990). New Source Review Workshop Manual: Prevention of Significant Deterioration and Nonattainment Area Permitting.

- "Clean Air Act: Title II - Emission Standards for Moving Sources". EPA. Archived from the original on May 1, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- Trendowski, John. "Sustainability Trends — Reducing Emissions at Airports" (PDF). Airport Magazine. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2010. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- "Aircraft Emissions Expected to Grow, but Technological and Operational Improvements and Government Policies Can Help Control Emissions" (PDF). U.S. Government Accountability Office. Retrieved April 22, 2012. Report no. GAO-09-554.

- "Clean Air Act". Cornell University Law School. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- "www.biodiesel.org" (PDF). The Clean Air Act's Clean-Fuel Vehicle Program. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- Shackleton, Abe (June 6, 2011). "What is Ethanol?". Open Fuel Standard. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- Shackleton, Abe (May 31, 2011). "What is Methanol?". Open Fuel Standard. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "Title III: General" Clean Air Act, United States. The Earth Encyclopedia. Updated: April 12, 2011. http://www.eoearth.org/article/Clean_Air_Act,_United_States

- CAA section 304, 42 U.S.C. § 7604.

- "Search - The Encyclopedia of Earth". editors.eol.org.

- "Title IV: Acid Deposition Control. Clean Air Act, United States. The Earth Encyclopedia. Updated: April 12, 2011".

- EPA. "Permits and Enforcement." The Plain English Guide to the Clean Air Act. Revised November 8, 2011.

- McCarthy, James (February 6, 2017). "Clean Air Act: A Summary of the Act and its Major Requirements" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- EPA (February 1998). "Air Pollution Operating Permit Program Update: Key Features and Benefits." Document no. EPA/451/K-98/002. p. 1.

- EPA. "Protecting the Stratospheric Ozone Layer." The Plain English Guide to the Clean Air Act. Revised November 8, 2011.

- "Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP) Program". US EPA. October 15, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- Jacobson, Mark Z. (April 2012). Air Pollution and Global Warming History, Science, and Solutions (Google Books) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 175, 176. ISBN 9781107691155.

- Clean Air Act of 1963, P.L. 88-206, 77 Stat. 392, December 17, 1963.

- Jacobson, Mark Z. (2002). Atmospheric Pollution: History, Science, and Regulation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-01044-3.

- EPA. "History of the Clean Air Act." Archived May 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Updated November 16, 2010.

- Clean Air Act Extension of 1970, 84 Stat. 1676, P.L. 91-604, December 31, 1970.

- EPA. "National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS)." Updated April 18, 2011.

- "Muskie Act". Toyota.

- EPA Alumni Association: William Ruckelshaus in a 2013 interview discusses his first-term efforts at implementing the Clean Air Act of 1970, Video, Transcript (see p14).

- Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977, P.L. 95-95, 91 Stat. 685, August 7, 1977.

- Turner, James Morton; Isenberg, Andrew C. (2018). The Republican Reversal: Conservatives and the Environment from Nixon to Trump. Harvard University Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 978-0674979970.

- EPA. "Reducing Toxic Air Pollutants." The Plain English Guide to the Clean Air Act. Revised November 8, 2011.

- Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990, P.L. 101-549, 104 Stat. 2399, November 15, 1990.

- United States. Clean Air Amendments of 1970. Pub.L. 91–604 Approved December 31, 1970.

- Former Deputy Administrator Hank Habicht talks about management at EPA. An Interview with Hank Habicht Video, Transcript (see p6). December 21, 2012.

- EPA. "What Are the Six Common Air Pollutants?" Revised July 1, 2010.

- EPA (2011). "The Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act from 1990 to 2020. Final Report." archived (also known as the "Second Prospective Study." archived)

- Cushman Jr.; John H. (June 26, 1997). "Clinton Sharply Tightens Air Pollution Regulations Despite Concern Over Costs". New York Times.

- Chebium, Raju (November 7, 2000). "U.S. Supreme Court hears clean air cases regarding smog and soot standards". CNN. Archived from the original on September 19, 2007.

- Cushman Jr.; John H. (June 25, 1997). "D'Amato Vows to Fight for E.P.A.'s Tightened Air Standards". New York Times.

- Greenhouse, Linda (February 28, 2001). "E.P.A.'s Right to Set Air Rules Wins Supreme Court Backing". New York Times.

- "EPA V. EME Homer City Generation, L.P., 134 S. Ct. 1584 (2014)". www.justice.gov. April 13, 2015.

- "Early Implementation of the Clean Air Act of 1970 in California." EPA Alumni Association. Video, Transcript (see p. 6). July 12, 2016.

- Rhode Island General Law, Title 23, Chapter 23, Section 2 (RIGL 23-23-2).

- "Early Implementation of the Clean Air Act of 1970 in California." EPA Alumni Association. Video, Transcript. July 12, 2016.

- Texas Department of Transportation (2010). "Metropolitan Planning Funds Administration. Section 5: Planning Process Self-Certification." TxDOT Manual System.

- Nelson, Gabriel (July 1, 2011). "D.C. Circuit Rejects EPA's Latest Guidance on Smog Standards". The New York Times.

- Nelson, Gabriel (May 3, 2011). "Republicans seek to spare smoggy Calif. areas from punishment". Environment & Energy News.

- "Shifting Gears: The Federal Government's Reversal on California's Clean Air Act Waiver | ACS" (PDF). American Constitution Society. February 11, 2019. Archived from the original on February 23, 2019. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- Liptak, Kevin (September 18, 2019). "Trump revokes waiver for California to set higher auto emissions standards". CNN. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- Davenport, Carol (September 20, 2019). "California Sues the Trump Administration in Its Escalating War Over Auto Emissions". The New York Times. Retrieved September 20, 2019.

- "Breathe Easy OK - Secondhand Smoke Laws". Ok.gov. July 1, 2002. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "Oregon ICAA". Oregon Health Authority. Oregon Public Health Division. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Environmental Protection Agency. "Fact Sheet: Clean Air Act Permitting for Greenhouse Gas Emissions – Final Rules" (PDF). EPA. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- EPA (2010). "Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2008." Document no. 430-R-10-006. Office of Atmospheric Programs.

- EPA, OAR, US (May 27, 2015). "Air Pollution: Current and Future Challenges". www.epa.gov. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- Miranda, Marie Lynn; Edwards, Sharon E.; Keating, Martha H.; Paul, Christopher J. (April 18, 2017). "Making the Environmental Justice Grade: The Relative Burden of Air Pollution Exposure in the United States". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 8 (6): 1755–1771. doi:10.3390/ijerph8061755. ISSN 1661-7827. PMC 3137995. PMID 21776200.

- Massey, Rachel (2004). "Environmental Justice: Income, Race, and Health" (PDF). Tufts University Global Development And Environment Institute, Tufts University.

- A Federal Advisory Committee to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2002). "ADVANCING ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE THROUGH POLLUTION PREVENTION A Report developed from the National Environmental Justice Advisory Council Meeting of December 9-13, 2002" (PDF). Environmental Protection Agency.

- "Clean Air Act (CAA) and Federal Facilities". US EPA. August 19, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Caterpillar Inc.#Clean Air Act violation 404 404

- United States et al. v. Hyundai Motor Company et al. (3 November 2014). Text

- Isen, Adam; Rossin-Slater, Maya; Walker, W. Reed (May 1, 2017). "Every Breath You Take – Every Dollar You'll Make: The Long-Term Consequences of the Clean Air Act of 1970". Journal of Political Economy. 125 (3): 848–902. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.589.9755. doi:10.1086/691465. ISSN 0022-3808.

- Ross, Kristie; Chmiel, James F.; Ferkol, Thomas (November 2012). "The impact of the Clean Air Act". The Journal of Pediatrics. 161 (5): 781–786. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.064. ISSN 0022-3476. PMC 4133758. PMID 22920509.

- "The Clean Air Act". Union of Concerned Scientists. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- "Environmental regulations drove steep declines in U.S. factory pollution". Berkeley News. August 9, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- Shapiro, Joseph S.; Walker, Reed (2018). "Why is Pollution from U.S. Manufacturing Declining? The Roles of Environmental Regulation, Productivity, and Trade". American Economic Review. 108 (12): 3814–3854. doi:10.1257/aer.20151272. ISSN 0002-8282.

- John Bachmann, David Calkins, Margo Oge. "Cleaning the Air We Breathe: A Half Century of Progress." EPA Alumni Association. September 2017. pp. 32–33.

- "The Clean Air Act – Was It Worth the Cost?". news.thomasnet.com. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

Further reading

- EPA Alumni Association. "Cleaning the Air We Breathe: A Half Century of Progress.". September 2016.

- Currie, Janet, and Reed Walker. 2019. "What Do Economists Have to Say about the Clean Air Act 50 Years after the Establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency?" Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33 (4): 3-26.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |