Chinese Filipino

Chinese Filipinos, often referred to as Filipino Chinese (and in Filipino as Pilipinong Tsino, Tsinoy, [tʃɪnoɪ] or Pilipinong Intsik [ɪntʃɪk]), are Filipinos of Chinese descent, mostly born and raised in the Philippines. Chinese Filipinos are one of the largest overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia.[1] In 2013, there were approximately 1.35 million Filipinos with Chinese ancestry.[2] In addition, Sangleys—Filipinos with at least some Chinese ancestry—comprise a substantial proportion of the Philippine population, although the actual figures are not known.[3][4]

Chinese-Filipina girl wearing the Maria Clara gown, the traditional gown of Filipina women | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1.35 million (as of 2013) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Metro Manila, Baguio, Metro Bacolod, Central Visayas, Metro Davao Iloilo, Pangasinan, Pampanga, Tarlac, Cagayan de Oro Vigan, Laoag, Laguna, Rizal, Lucena, Naga, Zamboanga City, Sulu | |

| Languages | |

| Filipino, English and other languages of the Philippines Hokkien, Mandarin, Cantonese, Teochew, Hakka Chinese, various other varieties of Chinese | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity (Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, P.I.C, Iglesia ni Cristo), minority Islam, Buddhism, Daoism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Sangley, Overseas Chinese |

| Chinese Filipino | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 咱儂 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 咱人 | ||||||||

| Hokkien POJ | Lán-nâng / Nán-nâng | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Chinese Filipino | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 華菲人 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 华菲人 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wade–Giles | Hua²-Fei¹-Ren² | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Huá Fēi Rén | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Chinese Filpinos are well represented in all levels of Filipino society.[5] Many Chinese Filipinos also play an important role in the Philippine business sector.[5][6][7][8][9]

Identity

The term "Filipino Chinese" may or may not be hyphenated.[10][11] The website of the organization Kaisa para sa Kaunlaran (Unity for Progress) omits the hyphen, adding that Filipino Chinese is the noun where "Filipino" is an adjective to the noun "Chinese." The Chicago Manual of Style and the APA, among others, also recommend dropping the hyphen. When used as an adjective, "Filipino Chinese" may take on a hyphenated form or may remain unchanged.[12][13][14]

There are various universally accepted terms used in the Philippines to refer to Chinese Filipinos:

- Chinese (Filipino: Tsino (Formal), Intsik referring Chinese British National 英籍 ; Chinese: 華人, Hoâ-jîn, Huáren)—often refers to all Chinese people in the Philippines regardless of nationality or place of birth.

- Chinese Filipino, Filipino Chinese, or Philippine Chinese (Filipino: Tsinoy, Chinoy; Intsik ; Chinese: 華菲, Hoâ-hui, Huáfēi)—refers to Chinese people with Philippine nationality, and to Chinese peoples with Chinese nationality but were born in the Philippines. This also includes Filipino Chinese who live and/or are born in the UK and are often referred to us "britsinoy".

- Lan-nang, Lán-lâng, Bân-lâm: Hokkienese (咱人, 福建人, Fújiànren)—a Hokkien term referring to Chinese Filipinos whose ancestry is from Fujian province.

- Keńg-tang-lâng: Cantonese (廣東人, Guǎngdōngren)—a Hokkien term referring to Chinese Filipinos whose ancestry is from Guangdong province.

- Chinese mestizo (Filipino: Mestisong Tsino, Chinese: 華菲混血, Chhut-si or Chhut-si-ia)—refers to people who are of mixed Chinese and indigenous Filipino ancestry. A common phenomenon in the Philippines; those with 75% Chinese ancestry are considered to be Chinese Filipino (Tsinoy), rather than Chinese mestizo.

- Mainland Chinese, Mainlander (Filipino: Taga-China; Chinese: 大陸仔 / 中國人, Tāi-dio̍k-á, Tiong-kok-lâng)—refers to Chinese people with Chinese nationality and were born in China.

- Taiwanese (Filipino: Taga-Taiwan; Chinese: 台灣人, Tâi-oân-lâng, Táiwānrén)—refers to Chinese people with Republic of China (Taiwan) nationality and were born in Taiwan.

- Tornatras or Torna atras—refers to people who are of varying mixtures of Chinese, Spanish, and indigenous Filipino during the Spanish Colonial Period.

Example of a Chinese influence in Filipino Spanish Architecture in St. Jerome Parish Church (Morong, Rizal)

Example of a Chinese influence in Filipino Spanish Architecture in St. Jerome Parish Church (Morong, Rizal)

Other terms being used with reference to China include:

- 華人 – Hoâ-jîn or Huárén—a generic term for referring to Chinese people, without implication as to nationality

- 華僑 – Hoâ-kiâo or Huáqiáo—Overseas Chinese, usually China-born Chinese who have emigrated elsewhere

- 華裔 – Hoâ-è or Huáyì—People of Chinese ancestry who were born in, residents of and citizens of another country

During the Spanish Colonial Period, the term Sangley was used to refer to people of unmixed Chinese ancestry while the term Mestizo de Sangley was used to classify persons of mixed Chinese and indigenous Filipino ancestry; both are now out of date in terms of usage.

"Indigenous Filipino", or simply "Filipino", is used in this article to refer to the Austronesian inhabitants prior to the Spanish Conquest of the islands. During the Spanish Colonial Period, the term Indio was used.

The Filipino Chinese has always been one of the largest ethnic groups in the country with Chinese immigrants comprising the largest group of immigrant settlers in the Philippines. They are one of the three major ethnic groupings in the Philippines, namely: Christian Filipinos (73% of the population-including indigenous ethnic minorities), Muslim Filipinos (5% of the population) and Chinese-Filipinos (27% of the population-including Chinese mestizos). Today, most Filipino Chinese are locally born. The rate of intermarriage between Chinese settlers and indigenous Filipinos is among the highest in Southeast Asia, exceeded only by Thailand. However, intermarriages occurred mostly during the Spanish colonial period because Chinese immigrants to the Philippines up to the 19th century were predominantly male. It was only in the 20th century that Chinese women and children came in comparable numbers. Today, Chinese Filipino male and female populations are practically equal in numbers. These Chinese mestizos, products of intermarriages during the Spanish colonial period, then often opted to marry other Chinese or Chinese mestizos . Generally, Chinese mestizos is a term referring to people with one Chinese parent.

By this definition, the ethnically Filipino Chinese comprise 1.8% (1.5 million) of the population.[15] This figure however does not include the Chinese mestizos who since Spanish times have formed a part of the middle class in Philippine society nor does it include Chinese immigrants from the People's Republic of China since 1949.

History

Early interactions

Ethnic Chinese sailed around the Philippine Islands from the 9th century onward and frequently interacted with the local Austronesian people. Chinese and Austronesian interactions initially commenced as bartering and items. This is evidenced by a collection of Chinese artifacts found throughout Philippine waters, dating back to the 10th century.

- Chinese (Sangley) in Precolonial/Early Spanish Philippines, c. 1590 via Boxer Codex

Chinese (Sangley) Couple Migrants in the Philippines, c. 1590

Chinese (Sangley) Couple Migrants in the Philippines, c. 1590 Chinese (Sangley) Couple Migrants in the Philippines, c. 1590

Chinese (Sangley) Couple Migrants in the Philippines, c. 1590.jpg)

Ming Dynasty Chinese General with Attendant, c. 1590

Ming Dynasty Chinese General with Attendant, c. 1590.jpg) Mandarin Bureaucrat with Wife from Ming Dynasty, c. 1590

Mandarin Bureaucrat with Wife from Ming Dynasty, c. 1590.jpg) Chinese nobility from Ming Dynasty China, c. 1590

Chinese nobility from Ming Dynasty China, c. 1590

Spanish colonial attitudes (16th century – 1898)

.jpg)

When the Spaniards arrived in the Philippines, there was already a significant population of migrants from China all of whom were male due to the relationship between the barangays (city-states) of the island of Luzon, and the Ming dynasty. The Chinese settlers were of various ethnic origins, most were Arab or Iranian while some were Jewish who were expelled from Quanzhou.

The first encounter of the Spanish authorities with China immigrants was not entirely pleasant – several Chinese pirates under the leadership of Limahong, who proceeded to besiege the newly established Spanish capital in Manila in 1574. He tried to capture the city of Manila in vain and was subsequently beaten by the combined Spanish and native forces under the leadership of Juan de Salcedo in 1575. Almost simultaneously, the Chinese imperial admiral Homolcong arrived in Manila where he was well received. On his departure he took with him two priests, who became the first Catholic missionaries to China from the Philippines. This visit was followed by the arrival of Chinese ships in Manila in May 1603 bearing Chinese officials with the official seal of the Ming Empire. This led to suspicion on the part of the Spaniards that the Chinese had sent a fleet to try to conquer the nearly defenseless islands. However, seeing the city as strongly defended as ever, the Chinese made no hostile moves. They returned to China without showing any particular motive for the journey, and without either side mentioning the apparent motive. Fortifications of Manila were started, with a Chinese settler in Manila named Engcang, who offered his services to the governor. He was refused, and a plan to massacre the Spaniards quickly spread among the Chinese inhabitants of Manila. The revolt was quickly crushed by the Spaniards, ending in a large-scale massacre of the non-Catholic Sangley in Manila. Throughout the Spanish Colonial Period, the China citizens who were mostly of mixed Arab, Iranian and Tanka trader descent called Sangley outnumbered the Spanish colonizers by ten to one due to extensive intermarriage with the native Filipinos, and at least on two occasions tried to seize power, but their revolts were quickly put down by joint forces composed of indigenous Filipinos, Japanese, and Spanish.[16](p138)

Following the mostly unpleasant initial interaction with the Spaniards, most of the mixed raced Arab and Iranian Sangley in Manila and in the rest of the Philippines started to focus on retail trade and service industry in order to avoid massacres and forced deportations to China. The Spanish authorities started restricting the activities of the Chinese immigrants and confined them to the Parían near Intramuros. With low chances of employment and prohibited from owning land, most of them engaged in small businesses or acted as skilled artisans to the Spanish colonial authorities. Most of the Chinese who arrived during the early Spanish period were Cantonese from "Canton, Nyngo, Chincheo, and Macau", who worked as stevedores and porters, as well as those skilled in the mechanical arts. From the mid-19th century, the Hokkienese migrants from Fujian would surpass and vastly outnumber the Cantonese migrants.

The Spanish authorities differentiated the Chinese immigrants into two groups: Parían (unconverted) and Binondo (converted). Many immigrants converted to Catholicism, and due to the lack of Chinese women, intermarried with indigenous women, and adopted Hispanized names and customs. The children of unions between indigenous Filipinos and Chinese were called Mestizos de Sangley or Chinese mestizos, while those between Spaniards and Chinese were called Tornatrás. The Chinese population originally occupied the Binondo area although eventually they spread all over the islands, and became traders, moneylenders, and landowners.[17]

Chinese mestizos as Filipinos

During the Philippine Revolution of 1898, Mestizos de Sangley (Chinese mestizos) would eventually refer to themselves as Filipino, which during that time referred to Spaniards born in the Philippines. The Chinese mestizos would later fan the flames of the Philippine Revolution. Many leaders of the Philippine Revolution themselves have substantial Chinese ancestry. These include Emilio Aguinaldo, Andrés Bonifacio, Marcelo del Pilar, Antonio Luna, José Rizal, and Manuel Tinio.[18]

Chinese mestizos in the Visayas

Sometime in the year 1750, an adventurous young man named Wo Sing Lok, also known as “Sin Lok” arrived in Manila, Philippines. The 12-year-old traveler came from Amoy, the old name for Xiamen, an island known in ancient times as “Gateway to China”—near the mouth of Jiulong “Nine Dragon” River in the southern part of Fujian province.

Earlier in Manila, immigrants from China were herded to stay in the Chinese trading center called "Parian". After the Sangley Revolt of 1603, this was destroyed and burned by the Spanish authorities. Three decades later, Chinese traders built a new and bigger Parian near Intramuros.

For fear of a Chinese uprising similar to that in Manila, the Spanish authorities implementing the royal decree of Gov. Gen. Juan de Vargas dated July 17, 1679, rounded up the Chinese in Iloilo and hamletted them in the parian (now Avanceña Street). It compelled all local unmarried Chinese to live in the Parian and all married Chinese to stay in Binondo. Similar Chinese enclaves or "Parian" were later established in Camarines Sur, Cebu, and Iloilo.[19]

Sin Lok together with the progenitors of the Lacson, Sayson, Ditching, Layson, Ganzon, Sanson and other families who fled Southern China during the reign of the despotic Qing dynasty (1644–1912) in the 18th century and arrived in Maynilad; finally, decided to sail farther south and landed at the port of Batiano river to settle permanently in “Parian” near La Villa Rica de Arevalo in Iloilo.[20][21]

Divided nationalism (1898–1946)

During the American colonial period, the Chinese Exclusion Act in the United States was also put into effect in the Philippines[22] Nevertheless, the Chinese were able to settle in the Philippines with the help of other Chinese Filipinos, despite strict American law enforcement, usually through "adopting" relatives from Mainland or by assuming entirely new identities with new names.

The privileged position of the Chinese as middlemen of the economy under Spanish colonial rule[23] quickly fell, as the Americans favored the principalía (educated elite) formed by Chinese mestizos and Spanish mestizos. As American rule in the Philippines started, events in Mainland China starting from the Taiping Rebellion, Chinese Civil War, and Boxer Rebellion led to the fall of the Qing Dynasty, which led thousands of Chinese from Fujian province in China to migrate en masse to the Philippines to avoid poverty, worsening famine, and political persecution. This group eventually formed the bulk of the current population of unmixed Chinese Filipinos.[18]

Formation of the Filipino Chinese identity (1946–1975)

Beginning in World War II, Chinese soldiers and guerrillas joined in the fight against the Japanese Imperial Forces during the Japanese Occupation in the Philippines (1941–1945). On April 9, 1942, many Chinese Filipino Prisoners of War were killed by Japanese Forces during the Bataan Death March after the fall of Bataan and Corregidor in 1942. Chinese Filipinos were integrated in the U.S. Armed Forces of the First & Second Filipino Infantry Regiments of the United States Army. After the Fall of Bataan and Corregidor in 1942, when Chinese Filipinos was joined the soldiers is a military unit of the Philippine Commonwealth Army under the U.S. military command is a ground arm of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) was started the battles between the Japanese Counter-Insurgencies and Allied Liberators from 1942 to 1945 to fought against the Japanese Imperial forces. Some Chinese-Filipinos joined the soldiers were integrated of the 11th, 14th, 15th, 66th & 121st Infantry Regiment of the U.S. Armed Forces in the Philippines – Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL) under the military unit of the Philippine Commonwealth Army started the Liberation in Northern Luzon and aided the provinces of Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, La Union, Abra, Mountain Province, Cagayan, Isabela and Nueva Vizcaya and attacking Imperial Japanese forces. Many Chinese-Filipinos joined the guerrilla movement of the Philippine-Chinese Anti-Japanese guerrilla resistance fighter unit or Wa Chi Movement, the Ampaw Unit under by Colonel Chua Sy Tiao and the Chinese-Filipino 48th Squadron since 1942 to 1946 to attacking Japanese forces. Thousands of Chinese Filipino soldiers and guerrillas died of heroism in the Philippines from 1941 to 1945 during World War II. Thousands of Chinese Filipino Veterans are interred in the Shrine of Martyr's Freedom of the Filipino Chinese in World War II located in Manila. The new-found unity between the ethnic Chinese migrants and the indigenous Filipinos against a common enemy – the Japanese, served as a catalyst in the formation of a Chinese Filipino identity who started to regard the Philippines as their one of their homes.[24]

Chinese as aliens under the dictatorship (1975–1987)

Under the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos, Chinese-Filipino who have citizenship referred only to those who arrived in the country before World War II, called "lao cao". Those who arrived after the war were later called the "jiu qiao". They were overstaying aliens and residents who came from China via Hong Kong in the 1950s to 1980s.[25]

Chinese schools in the Philippines, which were governed by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China (Taiwan), were transferred under the jurisdiction of the Philippine government's Department of Education. Virtually all Chinese schools were ordered closed or else to limit the time allotted for Chinese language, history, and culture subjects from 4 hours to 2 hours, and instead devote them to the study of Filipino languages and culture. Marcos' policies eventually led to the formal assimilation of the Chinese Filipinos into mainstream Filipino society,[26] although the majority were granted citizenship only after the dictatorship, under the administration of Corazon Aquino and Fidel Ramos.[27]

Following People Power Revolution (EDSA 1), the Chinese Filipinos quickly gained national spotlight as Cory Aquino, a Kapampangan Filipino with partial Chinese ancestry, eventually became president.[28]

Return of democracy (1987–2000)

Despite getting better protections after the dictatorship, crimes against Chinese-Filipinos were still present, the same way as crimes against other ethnic groups in the Philippines, as the country was still battling the lingering economic effects of the more than 2-decade Marcos dictatorship.[29][30] All these led to the formation of the first Chinese Filipino organization, Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran, Inc. (Unity for Progress) by Teresita Ang-See[n 1] which called for mutual understanding between the ethnic Chinese and the native Filipinos. Aquino encouraged free press and cultural harmony, a process which led to the burgeoning of the Chinese-language media[31] During this time, the third wave of Chinese migrants came. They are known as the "xin qiao", tourists or temporary visitors with fake papers, fake permanent residencies or fake Philippine passports that started coming starting the 1990s during the administration of Fidel Ramos and Joseph Estrada.[32]

21st century (2001–present)

More Chinese-Filipinos were given citizenship during the 21st century. Chinese influence in the country increased during the pro-Chinese presidency of Gloria Arroyo.[33] Businesses by the Filipino-Chinese improved under Benigno Aquino's presidency, while mainland Chinese migration into the Philippines decreased due to Aquino's pro-Filipino and US approach in handling disputes with communist China.[34] "Xin qiao" Chinese migration from mainland China into the Philippines intensified from 2016 up to the present,[35] due to controversial pro-Chinese policies by the Rodrigo Duterte presidency, prioritizing Chinese POGO businesses.[36]

The Filipino-Chinese community have expressed concern over the ongoing disputes between China and the Philippines, which majority preferring peaceful approaches to the dispute to safeguard their own private businesses.[37][38]

Origins

Virtually all Chinese in the Philippines belong to either the Hokkienese- or Cantonese-speaking groups of the Han Chinese ethnicity. Most Filipino-Chinese now are second or third generation, natural-born Philippine citizens who can still look back to their Chinese roots and have Chinese relatives both in China as well as in other Southeast Asian or Australasian or North American countries.

Minnan (Hokkienese) people

Chinese Filipinos who are classified as Minnan people (閩南人) have ancestors who came from southern Fujian and speak one of the Minnan dialects. They form the bulk of Chinese settlers in the Philippines after the Spanish Colonial Period, and settled primarily in Metro Manila and key cities in Luzon such as Angeles, Baguio, Dagupan, Ilagan, Laoag, Lucena, Tarlac, and Vigan, as well as in major Visayan and Mindanao cities such as Bacolod, Cagayan de Oro, Cotabato, Cebu, Davao, Dumaguete, General Santos, Iligan, Iloilo, Ormoc, Tacloban, Tagbilaran, and Zamboanga.

Minnan peoples, more popularly known as "Hokkienese", or "Fujianese" in English, or Lan-nang, Lán-lâng, Bân-lâm, Fújiànren in Chinese. The Minnan form 98.7% of all unmixed ethnic Chinese in the Philippines. Of the Minnan peoples, about 75% are from Quanzhou prefecture (specifically, Jinjiang City), 23% are from Zhangzhou prefecture, and 2% are from Xiamen City.[39] Minnan peoples started migrating to the Philippines in large numbers from the early 1800s and continue to the present, eventually outnumbering the Cantonese who had always formed the majority Chinese dialect group in the country.

According to a study of around 30,000 gravestones in the Manila Chinese Cemetery which writes the birthplace of those buried there, 66.46% were from Jinjiang City (Quanzhou), 17.63% from Nan'an, Fujian (Quanzhou), 8.12% from Xiamen in general, 2.96% from Hui'an County (Quanzhou), 1.55% from Longxi County (now part of Longhai City, Zhangzhou), 1.24% from Enming (Siming District, Xiamen), 1.17% from Quanzhou in general, 1.12% from Tong'an District (Xiamen), 0.85% from Shishi City (Quanzhou), 0.58% from Yongchun County (Quanzhou), and 0.54% from Anxi County (Quanzhou).[40]

The Minnan (Hokkienese) currently dominate the light industry and heavy industry, as well as the entrepreneurial and real estate sectors of the economy. Many younger Minnan people are also entering the fields of banking, computer science, engineering, finance, and medicine.

To date, most emigrants and permanent residents from Mainland China, as well as the vast majority of Taiwanese people in the Philippines are Minnan (Hokkienese) people.

Teochews

Linguistically related to the Hokkienese people are the Teochew (潮州人: Chaozhouren).

They migrated in large numbers to the Philippines during the Spanish Period by the thousands to the main Luzon island of Philippines,[41] but later on were eventually absorbed by intermarriage into the mainstream Hokkienese.

The Teochews are often mistaken for being Minnan people and Hokkiens.

Cantonese people

Filipino Chinese who are classified as Cantonese people (廣府人; Yale Gwóngfúyàhn) have ancestors who came from Guangdong province and speak one of the Cantonese dialects. They settled down in Metro Manila, as well as in major cities of Luzon such as Angeles, Naga, and Olongapo. Many also settled in the provinces of Northern Luzon (e.g., Benguet, Cagayan, Ifugao, Ilocos Norte).

The Cantonese (Guangdongnese) people (Keńg-tang-lâng, Guǎngdōngren) form roughly 1.2% of the unmixed ethnic Chinese population of the Philippines, with large numbers of descendants originally from the peasant villages of Taishan, Macau, and nearby areas. Many are not as economically prosperous as the Minnan (Hokkienese). Barred from owning land during the Spanish Colonial Period, most Cantonese were into the service industry, working as artisans, barbers, herbal physicians, porters (coulis), soap makers, and tailors. They also had no qualms in intermarrying with the local Filipinos and most of their descendants are now considered Filipinos, rather than Chinese or Chinese mestizos. During the early 1800s, Chinese migration from Cantonese-speaking areas in China to the Philippines trickled to almost zero, as migrants from Hokkienese-speaking areas gradually increased, explaining the gradual decrease of the Cantonese population. Presently, they are into small-scale entrepreneurship and in education.

Others

There are also some ethnic Chinese from nearby Asian countries and territories, most notably Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Hong Kong who are naturalized Philippine citizens and have since formed part of the Filipino Chinese community. Many of them are also Hokkien speakers, with a sizeable number of Cantonese and Teochew speakers.

Temporary resident Chinese businessmen and envoys include people from Beijing, Shanghai, and other major cities and provinces throughout China.

Demographics

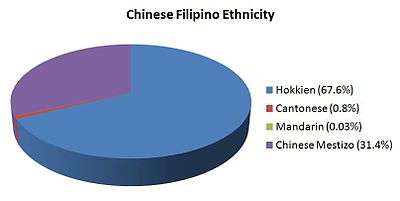

| Dialect | Population[42][43] |

|---|---|

| Hokkienese | 1,044,000 |

| Cantonese | 13,000 |

| Mandarin | 550 |

| Chinese mestizo* | 486,000 |

- The figure above denotes first-generation Chinese mestizos – namely, those with one Chinese, and one Filipino parent. This figure does not include those who have less than 50% Chinese ancestry, who are mostly classified as "Filipino".

The exact number of all Filipinos with some Chinese ancestry is unknown. Various estimates have been given from the start of the Spanish Colonial Period up to the present ranging from as low as 1% to as large as 18–27%. The National Statistics Office does not conduct surveys of ethnicity.[44]

According to a research report by historian Austin Craig who was commissioned by the United States in 1915 to ascertain the total number of the various races of the Philippines, the pure Chinese, referred to as Sangley, number around 20,000 (as of 1918), and that around one-third of the population of Luzon have partial Chinese ancestry. This comes with a footnote about the widespread concealing and de-emphasising of the exact number of Chinese in the Philippines.[45]

Another source dating from the Spanish Colonial Period shows the growth of the Chinese and the Chinese mestizo population to nearly 10% of the Philippine population by 1894.

| Race | Population (1810) | Population (1850) | Population (1894) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malay (i.e., indigenous Filipino) | 2,395,677 | 4,725,000 | 6,768,000 |

| mestizo de sangley (i.e., Chinese mestizo) | 120,621 | 240,000 | 500,000 |

| sangley (i.e., Unmixed Chinese) | 7,000 | 10,000 | 100,000 |

| Peninsular (i.e., Spaniard) | 4,000 | 25,000 | 35,000 |

| Total | 2,527,298 | 5,000,000 | 7,403,000 |

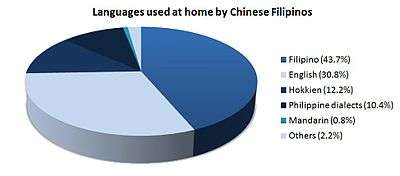

Language

The vast majority (74.5%) of Filipino Chinese speak Filipino as their native language. The majority of Filipino Chinese (77%) still retain the ability to understand and speak Hokkien as a second or third language.[46]

The use of Minnan (Hokkien) as first language is seemingly confined to the older generation, as well as in Chinese families living in traditional Chinese bastions, such as Binondo in Manila and Caloocan. In part due to the increasing adoption of Philippine nationality during the Marcos era, most Filipino Chinese born from the 1970s up to the mid-1990s tend to use Filipino or other Philippine regional languages, frequently admixed with both Minnan and English. Among the younger generation (born mid-1990s onward), the preferred language is English. Recent arrivals from Mainland China or Taiwan, despite coming from traditionally Minnan-speaking areas, typically use Mandarin among themselves.

Unlike other Overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia which featured a multiplicity of dialect groups, Filipino Chinese descend overwhelmingly from Minnan-speaking regions in Fujian province. Hence, Minnan (Hokkien) remains the ‘’lingua franca’’ among Filipinos Chinese. Mandarin, however, is perceived as the prestigious dialect, and it is used in all official and formal functions within the Chinese community, despite the fact that very few Chinese are conversant in Mandarin.[46]

For the Chinese mestizos, Spanish used to be the important commercial language and the preferred first language at the turn of the century. Starting from the American period, the use of Spanish gradually decreased and is now completely replaced by either English or Filipino.[47]

Minnan (Philippine Hokkien)

Since most of the Chinese in the Philippines trace their ancestry to the southern part of Fujian province in China, Minnan, otherwise known as Hokkienese is the lingua franca of Chinese Filipinos.

The variant of Minnan or Hokkienese spoken in the Philippines, Philippine Hokkien, is called locally as lan-lang-oe, meaning, "our people's language". Philippine Hokkien is mutually intelligible with other Minnan variants in China, Taiwan, and Malaysia, and is particularly close to the variant of Minnan spoken in Quanzhou. Its unique features include the presence of loanwords (Spanish, English, and Philippine language), excessive use of colloquial words (e.g., piⁿ-chu病厝: literally, "sick-house", instead of the Standard Minnan term pīⁿ-īⁿ: hospital; or chhia-tao: literally, "car-head", instead of the Standard Minnan term su-ki), and use of words from various variants within Minnan (such as Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, and Xiamen).

Due to the relatively small population of Filipino Chinese who are Cantonese, most of them, especially the new generation, never learned Cantonese.

Mandarin

Mandarin is the medium of instruction of Chinese subjects in Chinese schools in the Philippines. However, since the language is rarely used outside of the classroom, most Filipino Chinese would be hard-pressed to converse in Mandarin, much less read books using Chinese characters.

As a result of longstanding influence from the Ministry of Education of the Overseas Chinese Affairs Council of the Republic of China (Taiwan) since the early 1900s up to 2000, the Mandarin variant taught and spoken in the Philippines closely mirror that of Taiwan. While Traditional Chinese characters and the Bopomofo phonetic system are still used, instead of the Simplified characters and Pinyin phonetic system currently being used in both Mainland China and Singapore.

Cantonese

English

The vast majority of the Chinese in the Philippines are fluent in English – and around 30% of all Filipino Chinese, mostly those belonging to the younger generation, use English as their first language.

Filipino

As with English, the majority of Filipino Chinese speak the Philippine language of the region where they live (e.g., Filipino Chinese living in Manila speak Tagalog). Many Filipino Chinese, especially those living in the provinces, speak the regional language of their area as their first language.

Spanish

Spanish was an important language of the Chinese-Filipino, Chinese-Spanish, and Tornatras (Chinese-Spanish-Filipino) mestizos during most of the 20th century. Most of the elites of Philippine society during that time was made up of both Spanish mestizos and Chinese mestizos.

Many of the older generation Chinese (mainly those born before WWII), whether pure or mixed, can also understand some Spanish, due to its importance in commerce and industry.

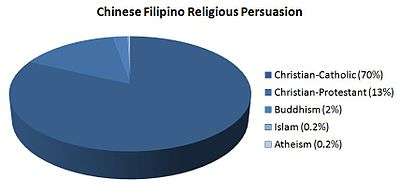

Religion

Chinese Filipinos are unique in Southeast Asia in being overwhelmingly Christian (83%).[46] Almost all Filipino Chinese, including the Chinese mestizos but excluding recent immigrants from either Mainland China or Taiwan, had or will have their marriages in a Christian church.[46]

Roman Catholicism

Majority (70%) of Christian Filipino Chinese are Roman Catholics.[46] Many Catholic Filipino Chinese still tend to practice the traditional Chinese religions side by side with Catholicism, due to the openness of the Church in accommodating Chinese beliefs such as ancestor veneration.

Unique to the Catholicism of Filipino Chinese is the religious syncretism that is found in Filipino Chinese homes. Many have altars bearing Catholic images such as the Santo Niño (Child Jesus) as well as statues of the Buddha and Taoist gods. It is not unheard of to venerate the Blessed Virgin Mary using joss sticks and otherwise Buddhist offerings, much as one would have done for Guan Yin or Mazu.[48]

Protestantism

.jpg)

Approximately 13% of all Christian Filipino Chinese are Protestants.[49]

Many Filipino Chinese schools are founded by Protestant missionaries and churches.

Filipino Chinese comprise a large percentage of membership in some of the largest evangelical churches in the Philippines, many of which are also founded by Filipino Chinese, such as the Christian Gospel Center, Christ's Commission Fellowship, United Evangelical Church of the Philippines, and the Youth Gospel Center.[50]

In contrast to Roman Catholicism, Protestantism forbids traditional Chinese practices such as ancestor veneration, but allows the use of meaning or context substitution for some practices that are not directly contradicted in the Bible (e.g., celebrating the Mid-Autumn Festival with moon cakes denoting the moon as God's creation and the unity of families, rather than the traditional Chinese belief in Chang'e). Many also had ancestors already practicing Protestantism while still in China.

Unlike ethnic Filipino-dominated Protestant churches in the Philippines which have very close ties with North American organizations, most Protestant Filipino Chinese churches instead sought alliance and membership with the Chinese Congress on World Evangelization, an organization of Overseas Chinese Christian churches throughout Asia.[51]

Chinese traditional religions and practices

A small number of Filipino Chinese (2%) continue to practise traditional Chinese religions solely.[52] Mahayana Buddhism, specifically, Chinese Pure Land Buddhism[53] Taoism[54] and ancestor worship (including Confucianism)[55] are the traditional Chinese beliefs that continue to have adherents among the Filipino Chinese.

Buddhist and Taoist temples can be found where the Chinese live, especially in urban areas like Manila.[n 2] Veneration of the Guanyin (觀音), known locally as Kuan-im either in its pure form or seen a representation of the Virgin Mary is practised by many Filipino Chinese.

Around half (40%) of all Filipino Chinese regardless of religion still claim to practise ancestor worship.[46] The Chinese, especially the older generations, have the tendency to go to pay respects to their ancestors at least once a year, either by going to the temple, or going to the Chinese burial grounds, often burning incense and bringing offerings like fruits and accessories made from paper.

Others

There are very few Filipino Muslim Chinese, most of whom live in either Mindanao or the Sulu Archipelago, and have intermarried or assimilated with their Moro neighbors. Many of them have attained prominent positions as political leaders. They include Datu Piang, Abdusakur Tan, and Michael Mastura, among such others.

Others are also members of the Iglesia ni Cristo, Jehovah's Witnesses, or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Some younger generations of Filipino Chinese also profess to be atheists.

Education

There are 150 Chinese schools that exist throughout the Philippines, slightly more than half of which operate in Metro Manila.[56] Filipino Chinese schools have an international reputation for producing award-winning students in the fields of science and mathematics, most of whom reap international awards in mathematics, computer programming, and robotics olympiads.[57]

History

The first school founded specifically for Chinese in the Philippines, the Anglo-Chinese school (now known as Tiong Se Academy) was opened in 1899 inside the Chinese Embassy grounds. The first curriculum called for rote memorization of the four major Confucian texts Four Books and Five Classics, as well as Western science and technology. This was followed suit by the establishment of other Chinese schools, such as Hua Siong College of Iloilo established in Iloilo in 1912, the Chinese Patriotic School established in Manila in 1912 and also the first school for Cantonese Chinese, Saint Stephen's High School established in Manila in 1915 and was the first sectarian school for the Chinese, and Chinese National School in Cebu in 1915.[56]

Burgeoning of Chinese schools throughout the Philippines as well as in Manila occurred from the 1920s until the 1970s, with a brief interlude during World War II, when all Chinese schools were ordered closed by the Japanese, and their students were forcibly integrated with Japanese-sponsored Philippine public education. After World War II, the Philippines and the Republic of China signed the Sino-Philippine Treaty of Amity, which provided for the direct control of the Republic of China (Taiwan)'s Ministry of Education over Chinese schools throughout the archipelago.

Such situation continued until 1973, when amendments made to the Philippine Constitution effectively transferred all Chinese schools to the authority of the Republic of the Philippines' Department of Education.[56] With this, the medium of instruction was shifted from Mandarin Chinese to English. Teaching hours relegated to Chinese language and arts, which featured prominently in the pre-1973 Chinese schools, were reduced. Lessons in Chinese geography and history, which were previously subjects in their own right, were integrated with the Chinese language subjects, whereas, the teaching of Filipino and Philippine history, civics, and culture became new required subjects.

The changes in Chinese education initiated with the 1973 Philippine Constitution led to the large shifting of mother tongues and assimilation of the Chinese Filipinos to general Philippine society. The older generation Filipino Chinese who were educated in the old curriculum typically used Chinese (e.g., Hokkien and Cantonese) at home, while most younger generation Filipino Chinese are more comfortable conversing in either English or Filipino admixed with Chinese.

Curriculum

Filipino Chinese schools typically feature curriculum prescribed by the Philippine Department of Education. The limited time spent in Chinese instruction consists largely of language arts.

The three core Chinese subjects are 華語 (Mandarin: Huáyŭ; Hokkien: Hoâ-gí, English: Chinese Grammar), 綜合 (Mandarin: Zōnghé; Hokkien: Chong-ha'p; English: Chinese Composition), and 數學 (Mandarin: Shùxué; Hokkien: Sòha'k; English: Chinese Mathematics). Other schools may add other subjects such as 毛筆 (Mandarin: Máobĭ; Hokkien: Mô-pit; English: Chinese calligraphy) . Chinese history, geography, and culture are integrated in all the three core Chinese subjects – they stood as independent subjects of their own before 1973. All Chinese subjects are taught in Mandarin Chinese, and in some schools, students are prohibited from speaking English, Filipino, or even Hokkien during Chinese classes.

Schools and Universities

Many Chinese Filipino schools are sectarian, being founded by either Roman Catholic or Protestant Chinese missions. These include Grace Christian College (Protestant-Baptist), Hope Christian High School (Protestant-Evangelical), Immaculate Conception Academy (Roman Catholic-Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception), Jubilee Christian Academy (Protestant-Evangelical), LIGHT Christian Academy (Protestant-Evangelical), Makati Hope Academy (Protestant-Evangelical), MGC-New Life Christian Academy (Protestant-Evangelical), Saint Peter the Apostle School (Roman Catholic-Archdiocese of Manila), Saint Jude Catholic School (Roman Catholic-Society of Divine Word), Saint Stephen's High School (Protestant-Episcopalian), Ateneo de Iloilo, Ateneo de Cebu, and Xavier School (Roman Catholic-Society of Jesus).

Major non-sectarian schools include Chiang Kai Shek College, Manila Patriotic School, Philippine Chen Kuang High School, Philippine Chung Hua School, Philippine Cultural College – the oldest Filipino Chinese secondary school in the Philippines, and Tiong Se Academy – the oldest Filipino Chinese school in the Philippines.

Chiang Kai Shek College is the only college in the Philippines accredited by both the Philippine Department of Education and the Republic of China (Taiwan) Ministry of Education.

Most Filipino Chinese attend Filipino Chinese schools until Secondary level, and then transfer to non-Chinese colleges and universities to complete their tertiary degree, due to the dearth of Chinese language tertiary institutions.

Name format

Most Filipino Chinese, particularly the younger generation, now follow the typical Western naming convention (given name, then family name), albeit with English first names coupled with Chinese surnames .

Historical trends in naming

Many Chinese who lived during the Spanish naming edict of 1849 eventually adopted Spanish name formats, along with a Spanish given name (e.g., Florentino Cu y Chua). Some adopted their entire Chinese name as a surname for the entire clan (e.g., Jose Antonio Chuidian from Shiu Tien or Chuy Dian; Alberto Cojuangco from 許寰哥, Khó-hoân-ko). Chinese mestizos, as well as some Chinese who chose to completely assimilate into the Filipino or Spanish culture, adopted Spanish surnames.

Newer Chinese migrants who came during the American Colonial Period use a combination of an adopted Spanish (or rarely, English) name together with their Chinese name (e.g., Carlos Palanca Tan Quin Lay or Vicente Go Tam Co). This trend was to continue up to the late 1970s.

As both exposure to North American media as well as the number of Filipino Chinese educated in English increased, the use of English names among Filipino Chinese, both common and unusual, started to increase as well. Popular names among the second generation Chinese community included English names ending in "-son" or other Chinese-sounding suffixes, such as Anderson, Emerson, Patrickson, Washington, among such others. For parents who are already third and fourth generation Filipino Chinese, English names reflecting American popular trends are given, such as Ethan, Austin, and Aidan.

It is thus not unusual to find a young Filipino Chinese named Chase Tan whose father's name is Emerson Tan and whose grandfather's name was Elpidio Tan Keng Kui, reflecting the depth of immersion into the English language as well as into the Philippine society as a whole.

Surnames

Filipino Chinese whose ancestors came to the Philippines from 1898 onward usually have single syllable Chinese surnames, the most common of which are Tan (陳), Ong (王), Lim (林), Go/Ngo (吳), Ng/Uy/Wong (黃), Gao/Kao (高), Chua/Cua (蔡), Sy/See/Si (施), Co (許), Lee/Dy (李), Ang/Hong/Hung (洪), Ching/Chong (莊), Sin (辛), Yao (姚), and Yap (葉)

Many also took on Spanish or Filipino surnames (e.g. Bautista, De la Cruz, De la Rosa, De los Santos, Garcia, Gatchalian, Mercado, Palanca, Robredo, Sanchez, Tagle, Torres etc.) upon naturalization. Today, it can be difficult to identify who are Filipino Chinese based on surnames alone.

A phenomenon common among Chinese migrants in the Philippines dating from the 1900s would be purchasing of surnames, particularly during the American Colonial Period, when the Chinese Exclusion Act was applied to the Philippines. Such law led new Chinese migrants to 'purchase' the surnames of Filipinos and thus pass off as long time Filipino residents of Chinese descent, or as ethnic Filipinos. Many also 'purchased' the Alien Landing Certificates of other Chinese who have gone back to China and assumed his surname and/or identity. Sometimes, younger Chinese migrants would circumvent the Act through adoption – wherein a Chinese with Philippine nationality adopts a relative or a stranger as his own children, thereby giving the adoptee automatic Filipino citizenship – and a new surname.

On the other hand, most Filipino Chinese whose ancestors came to the Philippines prior to 1898 use a Hispanicized surname (see below).

Hispanicized surnames

Filipino Chinese, as well as Chinese mestizos who trace their roots back to Chinese immigrants to the Philippines during the Spanish Colonial Period, usually have multiple syllable Chinese surnames such as Angseeco (from ang/see/co/kho) Aliangan (from liang/gan), Angkeko (from ang/ke/co/kho), Chuacuco, Chuatoco, Chuateco, Ciacho (from Sia), Sinco, Cinco (from Go), Cojuangco, Corong, Cuyegkeng, Dioquino, Dytoc, Dy-Cok, Dypiangco, Dysangco, Dytioco, Gueco, Gokongwei, Gundayao, Kimpo/Quimpo, King/Quing, Landicho, Lanting, Limcuando, Ongpin, Pempengco, Quebengco, Siopongco, Sycip, Tambengco, Tambunting, Tanbonliong, Tantoco, Tiolengco, Tiongson, Yuchengco, Tanciangco, Yuipco, Yupangco, Licauco, Limcaco, Ongpauco, Tancangco, Tanchanco, Teehankee, Uytengsu, and Yaptinchay among such others. These were originally full Chinese names which were transliterated into Spanish and adopted as surnames.[58]

There are also multiple syllable Chinese surnames that are Spanish transliterations of Hokkien words. Surnames like Tuazon (Eldest Grandson, 大孫), Dizon (Second Grandson, 二孫), Samson/Sanson (Third Grandson, 三孫), Sison (Fourth Grandson, 四孫), Gozon (Fifth Grandson, 五孫), Lacson (Sixth Grandson, 六孫) are examples of transliterations of designations that use the Hokkien suffix -son (孫) used as surnames for some Filipino Chinese who trace their ancestry from Chinese immigrants to the Philippines during the Spanish Colonial Period. The surname "Son/Sun" (孫) is listed in the classic Chinese text Hundred Family Surnames, perhaps shedding light on the Hokkien suffix -son used here as a surname alongside some sort of accompanying enumeration scheme.

The Chinese who survived the massacre in Manila in the 1700s fled to other parts of the Philippines and to hide their identity, they also adopted two-syllable Chinese surnames ending in “son” or “zon” and "co" such as: Yanson = Yan = 燕孫, Ganzon = Gan = 颜孫(Hokkien), Guanzon = Guan/Kwan = 关孫 (Cantonese), Tiongson/Tiongzon = Tiong = 钟孫 (Hokkien), Cuayson/Cuayzon = 邱孫 (Hokkien), Yuson = Yu = 余孫, Tingson/Tingzon = Ting = 陈孫 (Hokchew), Siason = Sia = 谢孫 (Hokkien).[59]

Many Filipinos who have Hispanicized Chinese surnames are no longer full Chinese, but are Chinese mestizos.

Food

Traditional Tsinoy cuisine, as Filipino Chinese home-based dishes are locally known, make use of recipes that are traditionally found in China's Fujian province and fuse them with locally available ingredients and recipes. These include unique foods such as hokkien chha-peng (Fujianese-style fried rice), si-nit mi-soa (birthday noodles), pansit canton (Fujianese-style e-fu noodles), hong ma or humba (braised pork belly), sibut (four-herb chicken soup), hototay (Fujianese egg drop soup), kiampeng (Fujianese beef fried rice), machang (glutinous rice with adobo), and taho (a dessert made of soft tofu, arnibal syrup, and pearl sago).

However, most Chinese restaurants in the Philippines, as in other places, feature Cantonese, Shanghainese and Northern Chinese cuisines, rather than traditional Fujianese fare.

Politics

With the increasing number of Chinese with Philippine nationality, the number of political candidates of Chinese-Filipino descent also started to increase. The most significant change within Filipino Chinese political life would be the citizenship decree promulgated by former President Ferdinand Marcos which opened the gates for thousands of Filipino Chinese to formally adopt Philippine citizenship.

Filipino Chinese political participation largely began with the People Power Revolution of 1986 which toppled the Marcos dictatorship and ushered in the Aquino presidency. The Chinese have been known to vote in blocs in favor of political candidates who are favorable to the Chinese community.

Important Philippine political leaders with Chinese ancestry include the current and former presidents Rodrigo Duterte, Benigno Aquino III, Cory Aquino, Sergio Osmeña, and Ferdinand Marcos, former senators Nikki Coseteng, Alfredo Lim, and Roseller Lim, as well as several governors, congressmen, and mayors throughout the Philippines. Many ambassadors and recent appointees to the presidential cabinet are also Filipino Chinese like Arthur Yap.

The late Cardinal Jaime Sin and Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle also have Chinese ancestry.

Society and culture

Society

The Filipino Chinese are mostly business owners and their life centers mostly in the family business. These mostly small or medium enterprises play a significant role in the Philippine economy. A handful of these entrepreneurs run large companies and are respected as some of the most prominent business tycoons in the Philippines.

Filipino Chinese attribute their success in business to frugality and hard work, Confucian values and their traditional Chinese customs and traditions. They are very business-minded and entrepreneurship is highly valued and encouraged among the young. Most Filipino Chinese are urban dwellers. An estimated 50% of the Filipino Chinese live within Metro Manila, with the rest in the other major cities of the Philippines. In contrast with the Chinese mestizos, few Chinese are plantation owners. This is partly due to the fact that until recently when the Filipino Chinese became Filipino citizens, the law prohibited the non-citizens, which most Chinese were, from owning land.

Culture

As with other Southeast Asian nations, the Chinese community in the Philippines has become a repository of traditional Chinese culture common to unassimilated ethnic minorities throughout the world. Whereas in mainland China many cultural traditions and customs were suppressed during the Cultural Revolution or simply regarded as old-fashioned nowadays, these traditions have remained largely untouched in the Philippines.

Many new cultural twists have evolved within the Chinese community in the Philippines, distinguishing it from other overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. These cultural variations are highly evident during festivals such as Chinese New Year and Mid-Autumn Festival. The Filipino Chinese have developed unique customs pertaining to weddings, birthdays, and funerary rituals.

Wedding traditions of Filipino Chinese, regardless of religious persuasion, usually involve identification of the dates of supplication/pamamanhikan (kiu-hun), engagement (ting-hun), and wedding (kan-chhiu) adopted from Filipino customs, through feng shui based on the birthdates of the couple, as well as of their parents and grandparents. Certain customs found among Filipino Chinese include the following: During supplication (kiu-hun), a solemn tea ceremony within the house of the groom ensues where the couple will be served tea, egg noodles (misua), and given ang-paos (red packets containing money). During the supplication ceremony, pregnant women and recently engaged couples are forbidden from attending the ceremony. Engagement (ting-hun) quickly follows, where the bride enters the ceremonial room walking backward and turned three times before being allowed to see the groom. A welcome drink consisting of red-colored juice is given to the couple, quickly followed by the exchange of gifts for both families and the Wedding tea ceremony, where the bride serves the groom's family, and vice versa. The engagement reception consists of sweet tea soup and misua, both of which symbolizes long-lasting relationship. Before the wedding, the groom is expected to provide the matrimonial bed in the future couple's new home. A baby born under the Chinese sign of the Dragon may be placed in the bed to ensure fertility. He is also tasked to deliver the wedding gown to his bride on the day prior to the wedding to the sister of the bride, as it is considered ill fortune for the groom to see the bride on that day. For the bride, she prepares an initial batch of personal belongings (ke-chheng) to the new home, all wrapped and labeled with the Chinese characters for sang-hi. On the wedding date, the bride wears a red robe emblazoned with the emblem of a dragon prior to wearing the bridal gown, to which a pair of sang-hi (English: marital happiness) coin is sewn. Before leaving her home, the bride then throws a fan bearing the Chinese characters for sang-hi toward her mother to preserve harmony within the bride's family upon her departure. Most of the wedding ceremony then follows Catholic or Protestant traditions. Post-Wedding rituals include the two single brothers or relatives of the bride giving the couple a wa-hoe set, which is a bouquet of flowers with umbrella and sewing kit, for which the bride gives an ang-pao in return. After three days, the couple then visits the bride's family, upon which a pair of sugar cane branch is given, which is a symbol of good luck and vitality among Hokkien people.[60]

Birthday traditions of Filipino Chinese involves large banquet receptions, always featuring noodles[61] and round-shaped desserts. All the relatives of the birthday celebrant are expected to wear red clothing which symbolize respect for the celebrant. Wearing clothes with a darker hue is forbidden and considered bad luck. During the reception, relatives offer ang paos (red packets containing money) to the birthday celebrant, especially if he is still unmarried. For older celebrants, boxes of egg noodles (misua) and eggs on which red paper is placed are given.

Births of babies are not celebrated and they are usually given pet names, which he keeps until he reaches first year of age. The Philippine custom of circumcision is widely practiced within the Filipino Chinese community regardless of religion, albeit at a lesser rate as compared to ethnic Filipinos . First birthdays are celebrated with much pomp and pageantry, and grand receptions are hosted by the child's paternal grandparents.

Funerary traditions of Filipino Chinese mirror those found in Fujian. A unique tradition of many Filipino Chinese families is the hiring of professional mourners which is alleged to hasten the ascent of a dead relative's soul into Heaven. This belief particularly mirrors the merger of traditional Chinese beliefs with the Catholic religion.[62]

Subculture according to Acculturation

Filipino Chinese, especially in Metro Manila, are also divided into several social types. These types are not universally accepted as a fact, but are nevertheless recognized by most Filipino Chinese to be existent. These reflect an underlying generational gap within the community.:[63]

- Culturally pure Chinese—Consists of Filipino Chinese who speaks fluent Hokkien and heavily accented Filipino and/or English. Characterized as the "traditional shop-keeper image", they hardly socialize outside the Chinese community and insist on promoting Chinese language and values over others, and acculturation as opposed to assimilation into the general Philippine community. Most of the older generation and many of the younger ones belong to this category.

- Binondo/Camanava Chinese—Consists of Filipino Chinese who speaks fluent Hokkien and good Filipino and/or English. Their social contacts are largely Chinese, but also maintain contacts with some Filipinos. Most of them own light or heavy industry manufacturing plants, or are into large-scale entrepreneurial trading and real estate. Most tycoons such as Henry Sy, Lucio Tan, and John Gokongwei would fall into this category, as well as most Filipino Chinese residing in Binondo district of Manila, Caloocan, Malabon, Navotas, and Valenzuela, hence the term.

- Greenhills/Quezon City Chinese—Consists of Filipino Chinese who prefer to speak English (or Taglish) as their first language, but poor or passable Hokkien and Mandarin. Most belong to the younger generation of Manila-based Chinese. Culturally, they are influenced by Western/Filipino thought and culture. Many enter the banking, computer science, engineering, finance, and medical professions. Many live in the Greenhills area and in the La Loma, New Manila, Sta. Mesa Heights, and Corinthian Garden districts of Quezon City, hence the term.

- Probinsyanong Chinese—Consists of Filipino Chinese who largely reside outside of Metro Manila. They speak Tagalog, Cebuano, or a Philippine language, but are fluent in English, and mostly poor in Hokkien. They are known by other Chinese as the probinsyanong Intsik.

Subculture according to Period of arrivals

Most of the Chinese mestizos, especially the landed gentry trace their ancestry to the Spanish era. They are the "First Chinese" or Sangley whose descendants nowadays are mostly integrated into Philippine society. Most are from Guangdong province in China, with a minority coming from Fujian. They have embraced a Hispanized Filipino culture since the 17th century. After the end of Spanish rule, their descendants, the Chinese mestizos, managed to invent a cosmopolitan mestizo culture coupled with an extravagant Mestizo de Sangley lifestyle, intermarrying either with ethnic Filipinos or with Spanish mestizos.

The largest group of Chinese in the Philippines are the "Second Chinese," who are descendants of migrants in the first half of the 20th century, between the anti-Manchu 1911 Revolution in China and the Chinese Civil War. This group accounts for most of the "full-blooded" Chinese. They are almost entirely from Fujian province.

The "Third Chinese" are the second largest group of Chinese, the recent immigrants from Mainland China, after the Chinese economic reform of the 1980s. Generally, the "Third Chinese" are the most entrepreneurial and have not totally lost their Chinese identity in its purest form and seen by some "Second Chinese" as a business threat. Meanwhile, continuing immigration from Mainland China further enlarge this group[64]

Civic organizations

Aside from their family businesses, Filipino Chinese are active in Chinese-oriented civic organizations related to education, health care, public safety, social welfare and public charity. As most Filipino Chinese are reluctant to participate in politics and government, they have instead turned to civic organizations as their primary means of contributing to the general welfare of the Chinese community. Beyond the traditional family and clan associations, Filipino Chinese tend to be active members of numerous alumni associations holding annual reunions for the benefit of their Chinese-Filipino secondary schools.[65]

Outside of secondary schools catering to Filipino Chinese, some Filipino Chinese businessmen have established charitable foundations that aim to help others and at the same time minimize tax liabilities. Notable ones include the Gokongwei Brothers Foundation, Metrobank Foundation, Tan Yan Kee Foundation, Angelo King Foundation, Jollibee Foundation, Alfonso Yuchengco Foundation, Cityland Foundation, etc. Some Chinese-Filipino benefactors have also contributed to the creation of several centers of scholarship in prestigious Philippine Universities, including the John Gokongwei School of Management at Ateneo de Manila, the Yuchengco Center at De La Salle University, and the Ricardo Leong Center of Chinese Studies at Ateneo de Manila. Coincidentally, both Ateneo and La Salle enroll a large number of Chinese-Filipino students. In health care, Filipino Chinese were instrumental in establishing and building medical centers that cater for the Chinese community such as the Chinese General Hospital and Medical Center, the Metropolitan Medical Center, Chong Hua Hospital and the St. Luke's Medical Center, Inc., one of Asia's leading health care institutions. In public safety, Teresita Ang See's Kaisa, a Chinese-Filipino civil rights group, organized the Citizens Action Against Crime and the Movement for the Restoration of Peace and Order at the height of a wave of anti-Chinese kidnapping incidents in the early 1990s.[66] In addition to fighting crime against Chinese, Filipino Chinese have organized volunteer fire brigades all over the country, reportedly the best in the nation.[67] that cater to the Chinese community. In the arts and culture, the Bahay Tsinoy and the Yuchengco Museum were established by Filipino Chinese to showcase the arts, culture and history of the Chinese.[68]

Ethnic Chinese perception of Filipinos

Filipinos were initially referred to as hoan-á (番仔) by ethnic Chinese in the Philippines. It is also used in other Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia and Singapore by Hokkien speaking ethnic Chinese to refer to peoples of Malay ancestry. The term itself originally meant "foreigner/barbarian/outsider" since for centuries this was the term predominantly used to refer to non-Chinese people, but today, it does not necessarily carry its original connotations, depending on the speaker's perceptions of how they learned to perceive the term. When speaking Hokkien, most older Chinese still use the term, while younger Chinese may sometimes instead use the term hui-li̍p-pin lâng (菲律宾人), which directly means, "Philippine person", or simply "Filipino".

Filipino Chinese generally perceive the government and authorities to be unsympathetic to the plight of the ethnic Chinese, especially in terms of frequent kidnapping for ransom. While the vast majority of older generation Filipino Chinese still remember the rabid anti-Chinese taunts and the anti-Chinese raids and searches done by the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) and Bureau of Immigration, most of the third or fourth generation Filipino Chinese generally view the Philippine people and government positively, and have largely forgotten about the historical oppression of the ethnic Chinese. They are also most likely to consider themselves as "Filipino" and support the Philippines, rather than China or Taiwan.

Some Filipino Chinese believe racism still exists toward their community among a minority of Filipinos, who the Chinese refer to as pai-hua (排華) in the local Minnan dialect. Organizations belonging to this category include the Laspip Movement, headed by Adolfo Abadeza, as well as the Kadugong Liping Pilipino, founded by Armando Ducat, Jr..[69]

Intermarriage

Chinese mestizos are persons of mixed Chinese and either Spanish or indigenous Filipino ancestry. They are thought to make up as much as 25% of the country's total population. A number of Chinese mestizos have surnames that reflect their heritage, mostly two or three syllables that have Chinese roots (e.g., the full name of a Chinese ancestor) with a Hispanized phonetic spelling.

During the Spanish colonial period, the Spanish authorities encouraged the Chinese male immigrants to convert to Catholicism. Those who converted got baptized and their names Hispanized, and were allowed to intermarry with indigenous women. They and their mestizo offspring became colonial subjects of the Spanish crown, and as such were granted several privileges and afforded numerous opportunities denied to the unconverted, non-citizen Chinese. Starting as traders, they branched out into landleasing, moneylending and later, landholding.

Chinese mestizo men and women were encouraged to marry Spanish and indigenous women and men, by means of dowries, in a policy to mix the races of the Philippines so it would be impossible to expel the Spanish.[70](p86)

In these days however, blood purity is still of prime concern in most traditional Chinese-Filipino families especially pure-blooded ones. The Chinese believe that a Chinese must only be married to a fellow Chinese since the marriage to a Filipino or any outsider was considered taboo.

Chinese marriage to Filipinos and outsiders posts uncertainty on both parties. The Chinese family structure is patriarchal hence, it is the male that carries the last name of the family which also carries the legacy of the family itself. Male Chinese marriage to a Filipina or any outsider is more admissible than vice versa. In the case of the Chinese female marrying a Filipino or any outsider, it may cause several unwanted issues especially on the side of the Chinese family.

In some instances, a member of a traditional Chinese-Filipino family may be denied of his or her inheritance and likely to be disowned by his or her family by marrying an outsider without their consent. However, there are exceptions in which intermarriage to a Filipino or any outsider is permissible provided the aforementioned's family is well-off and/or influential.

On the other hand, modern Chinese-Filipino families allow their children to marry a Filipino or any outsider. However, many of them would still prefer that the Filipino or any outsider would have some or little Chinese blood.

Trade and industry

Like much of Southeast Asia, ethnic Chinese dominate Philippine commerce at every level of society.[5][76][77] Filipino Chinese wield a tremendous economic clout unerringly disproportionate to their small population size over their indigenous Filipino majority counterparts and play a critical role in maintaining the country's economic vitality and prosperity.[7][78] With their powerful economic prominence, the Chinese virtually make up the country's entire wealthy elite.[75][79][80] Filipino Chinese in the aggregate, represent a disproportionate wealthy, market-dominant minority not only form a distinct ethnic community, they also form, by and large, an economic class: the commercial middle and upper class in contrast to the poorer indigenous Filipino majority working and underclass.[5][80] Entire posh Chinese enclaves have sprung up in major Filipino cities across the country, literally walled off from the poorer indigenous Filipino masses guarded by heavily armed, private security forces.[5]

Ethnic Chinese have been major players in the Filipino business sector and dominated the economy of the Philippines for centuries long before the pre-Spanish and American colonial eras.[81] Long before the Spanish conquest of the Philippines, Chinese merchants carried on trading activities with native communities along the coast of modern Mainland China. By the time the Spanish arrived, Chinese controlled all the trading and commercial activities, serving as retailers, artisans, and providers of food for various Spanish settlements.[8] During the American colonial epoch, ethnic Chinese controlled a large percentage of the retail trade and internal commerce of the country. They predominated the retail trade and owned 75 percent of the 2,500 rice mills scattered along the Filipino islands.[82] Total resources of banking capital held by the Chinese was $27 million in 1937 to a high of $100 million in the estimated aggregate, making them second to the Americans in terms of total foreign capital investment held.[8] Under Spanish rule, Chinese were willing to engage in trade and other business activities. They were responsible for introducing sugar refining devices, new construction techniques, moveable type printing, and bronze making. Chinese also provided fishing, gardening, artisan, and other trading services. Many Chinese were drawn to business as they were prohibited from owning land and saw the only way out of poverty was through business and entrepreneurship, to take charge of their own financial destinies by becoming self-employed as vendors, retailers, traders, collectors, and distributors of goods and services.[83] Mainly attracted by the economic opportunity during the first four decades of the 20th century, American colonization of the Philippines allowed the Chinese to secure their economic clout among their entrepreneurial pursuits. The implementation of a free trade policy between the Philippines and the United States allowed the Chinese to take advantage of a burgeoning Filipino consumer market. As a result, Filipino Chinese were able to capture a significant market share by expanding their business lines in which they were the major players and ventured into then newly flourishing industries such as industrial manufacturing and financial services.[84]

Ethnic Chinese entrepreneurs are estimated to control 60 to 70 percent of the Philippine economy.[6][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93] Filipino Chinese, comprising 1 of the population, control many of the Philippines' largest and most lucrative department store chains, supermarkets, hotels, shopping malls, airlines and fast-food restaurants in addition to all the major financial services corporations, banks and stock brokerage firms, and they dominate the nation's wholesale distribution networks, shipping, banking, construction, textiles, real estate, personal computer, semiconductors, pharmaceutical, media, and industrial manufacturing industries.[6][75][94] The Chinese are also involved in the processing and distribution of pharmaceutical products. More than 1000 firms are involved in this industry, with most being small and medium-sized companies with a total capitalization of 1.2 billion pesos.[95] Filipino Chinese also control six out of the ten English-language newspapers in Manila, including the one with the largest daily circulation.[75] Stores and restaurants around the country are owned by most of the leading entrepreneurs of Chinese extraction are regularly featured in Manila newspapers which attracted great public interest and were used to illustrate the Chinese community's strong economic influence.[96][97] Of the 66 percent remaining part of the economy in the Philippines held by either ethnic Chinese or Filipinos, the Chinese control 35 percent of all total sales.[98] Filipinos of Chinese origin control an estimated 50 to 60 percent of non-land share capital in the Philippines, and as much as 35 percent of total sales are attributed to the largest public and private firms controlled by ethnic Chinese.[99] They essentially focus on sectors such as semiconductors and chemicals, real estate, land, and property development, banking, engineering, construction, fiber, textiles, finance, consumer electronics, food, and personal computers.[100] A third of the top 500 companies on the Philippines stock exchange are Chinese-owned.[101] Of the top 1000 firms, Filipino Chinese owned 36 percent. Among the top 100 companies, 43 percent were owned by Chinese-Filipinos.[101] Between 1978 and 1988, Chinese controlled 146 of the country's 494 top companies.[102] Ethnic Chinese are estimated to control over one-third of the 1000 largest corporations and Chinese entrepreneurs control 47 of the 68 locally owned public companies.[103][104] 55 percent of overall Filipino private business is also generated by ethnic Chinese.[105] Chinese owned companies account for 66 percent of the sixty largest commercial entities.[106][107] In 2015, the top four wealthiest people in the Philippines (and ten out of the top fifteen) were ethnic Chinese.[94]

As Filipino Chinese entrepreneurs became more financially prosperous, they often pooled large amounts of seed capital and started joint ventures with Overseas Chinese business moguls and investors from all over the world. Filipino Chinese businesses link up with other ethnic Overseas Chinese businesses and networks concentrate on various industry sectors such as real estate development, engineering, textiles, consumer electronics, financial services, food, semiconductors, and chemicals.[108] Many Filipino Chinese entrepreneurs are particularly strong adherents to the Confucian paradigm of intrapersonal relationships when doing business with each other.[109] Filipino Chinese entrepreneurs are particularly strong adherents to the Confucian paradigm of intrapersonal relationships. The spectacular growth of the Filipino Chinese business tycoons have allowed many Filipino Chinese corporations to start joint ventures with increasing numbers of expatriate Mainland Chinese investors.[110] Many Filipino Chinese entrepreneurs have a proclivity to reinvest most of their business profits for expansion. A small percentage of the firms were managed by Chinese with entrepreneurial talent, were able to grow their small enterprises into gargantuan conglomerates.[78] The term "Chinoy" is used in Filipino newspapers to refer to individuals with a degree of Chinese parentage who either speak a Chinese dialect or adhere to Chinese customs. Ethnic Chinese also dominate the Filipino telecommunications industry, where one of the current significant players in the industry is taipan John Gokongwei, whose conglomerate company JG Summit Holdings controls 28 wholly owned subsidiaries with interests ranging from food and agro-industrial products, hotels, insurance brokering, financial services, electronic components, textiles and garments, real estate, petrochemicals, power generation, printing services, newspaper, packaging materials, detergent products, and cement.[111] Gokongwei started out in food processing in the 1950s, venturing into textile manufacturing in the early 1970s, and then became active in real estate development and hotel management in the late 1970s. In 1976, Gokongwei established the Manila Midtown Hotels and now controls the Cebu Midtown hotel chain and the Manila Galeria Suites. In addition, he also owns substantial interests in PCI Bank and Far East Bank as well as one of the nation's oldest newspapers, The Manila Times.[112][113] Gokongwei's eldest daughter became publisher of the newspaper in December 1988 at the age of 28, at which during the same time her father acquired the paper from the Roceses, a Spanish Mestizo family.[114]