Chicken

The chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) is a type of domesticated fowl, a subspecies of the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus). Chickens are one of the most common and widespread domestic animals, with a total population of 23.7 billion as of 2018.[1] up from more than 19 billion in 2011.[2] There are more chickens in the world than any other bird or domesticated fowl.[2] Humans keep chickens primarily as a source of food (consuming both their meat and eggs) and, less commonly, as pets. Originally raised for cockfighting or for special ceremonies, chickens were not kept for food until the Hellenistic period (4th–2nd centuries BC).[3][4]

| Chicken | |

|---|---|

| |

| A rooster or cock (left) and hen (right) perching on a roost. | |

Domesticated | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Phasianidae |

| Genus: | Gallus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | G. g. domesticus |

| Trinomial name | |

| Gallus gallus domesticus | |

Genetic studies have pointed to multiple maternal origins in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia,[5] but with the clade found in the Americas, Europe, the Middle East and Africa originating in the Indian subcontinent. From ancient India, the domesticated chicken spread to Lydia in western Asia Minor, and to Greece by the 5th century BC.[6] Fowl had been known in Egypt since the mid-15th century BC, with the "bird that gives birth every day" having come to Egypt from the land between Syria and Shinar, Babylonia, according to the annals of Thutmose III.[7][8][9]

Terminology

In the UK and Ireland, adult male chickens over the age of one year are primarily known as cocks, whereas in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, they are more commonly called roosters. Males less than a year old are cockerels.[10] Castrated or neutered roosters are called capons (surgical and chemical castration are now illegal in some parts of the world). Females over a year old are known as hens, and younger females as pullets,[11] although in the egg-laying industry, a pullet becomes a hen when she begins to lay eggs, at 16 to 20 weeks of age. In Australia and New Zealand (also sometimes in Britain), there is a generic term chook /tʃʊk/ to describe all ages and both sexes.[12] The young are often called chicks.

Chicken originally referred to young domestic fowl.[13] The species as a whole was then called domestic fowl, or just fowl. This use of chicken survives in the phrase Hen and Chickens, sometimes used as a British public house or theatre name, and to name groups of one large and many small rocks or islands in the sea .

In the Deep South of the United States, chickens are referred to by the slang term yardbird.[14]

General biology and habitat

Chickens are omnivores.[15] In the wild, they often scratch at the soil to search for seeds, insects and even animals as large as lizards, small snakes,[16] or young mice.[17]

The average chicken may live for five to ten years, depending on the breed.[18] The world's oldest known chicken was a hen which died of heart failure at the age of 16 years according to the Guinness World Records.[19]

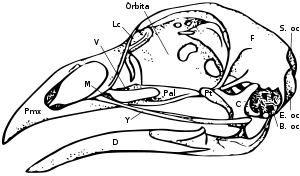

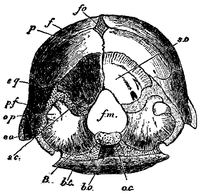

Roosters can usually be differentiated from hens by their striking plumage of long flowing tails and shiny, pointed feathers on their necks (hackles) and backs (saddle), which are typically of brighter, bolder colours than those of females of the same breed. However, in some breeds, such as the Sebright chicken, the rooster has only slightly pointed neck feathers, the same colour as the hen's. The identification can be made by looking at the comb, or eventually from the development of spurs on the male's legs (in a few breeds and in certain hybrids, the male and female chicks may be differentiated by colour). Adult chickens have a fleshy crest on their heads called a comb, or cockscomb, and hanging flaps of skin either side under their beaks called wattles. Collectively, these and other fleshy protuberances on the head and throat are called caruncles. Both the adult male and female have wattles and combs, but in most breeds these are more prominent in males. A muff or beard is a mutation found in several chicken breeds which causes extra feathering under the chicken's face, giving the appearance of a beard. Domestic chickens are not capable of long distance flight, although lighter chickens are generally capable of flying for short distances, such as over fences or into trees (where they would naturally roost). Chickens may occasionally fly briefly to explore their surroundings, but generally do so only to flee perceived danger.

Behavior

Social behaviour

.jpg)

Chickens are gregarious birds and live together in flocks. They have a communal approach to the incubation of eggs and raising of young. Individual chickens in a flock will dominate others, establishing a "pecking order", with dominant individuals having priority for food access and nesting locations. Removing hens or roosters from a flock causes a temporary disruption to this social order until a new pecking order is established. Adding hens, especially younger birds, to an existing flock can lead to fighting and injury.[20] When a rooster finds food, he may call other chickens to eat first. He does this by clucking in a high pitch as well as picking up and dropping the food. This behaviour may also be observed in mother hens to call their chicks and encourage them to eat.

A rooster's crowing is a loud and sometimes shrill call and sends a territorial signal to other roosters.[21] However, roosters may also crow in response to sudden disturbances within their surroundings. Hens cluck loudly after laying an egg, and also to call their chicks. Chickens also give different warning calls when they sense a predator approaching from the air or on the ground.[22]

Courtship

To initiate courting, some roosters may dance in a circle around or near a hen ("a circle dance"), often lowering the wing which is closest to the hen.[23] The dance triggers a response in the hen[23] and when she responds to his "call", the rooster may mount the hen and proceed with the mating.

More specifically, mating typically involves the following sequence: 1. Male approaching the hen. 2. Male pre-copulatory waltzing. 3. Male waltzing. 4. Female crouching (receptive posture) or stepping aside or running away (if unwilling to copulate). 5. Male mounting. 6. Male treading with both feet on hen's back. 7. Male tail bending (following successful copulation).[24]

Nesting and laying behaviour

Hens will often try to lay in nests that already contain eggs and have been known to move eggs from neighbouring nests into their own. The result of this behaviour is that a flock will use only a few preferred locations, rather than having a different nest for every bird. Hens will often express a preference to lay in the same location. It is not unknown for two (or more) hens to try to share the same nest at the same time. If the nest is small, or one of the hens is particularly determined, this may result in chickens trying to lay on top of each other. There is evidence that individual hens prefer to be either solitary or gregarious nesters.[25]

Broodiness

Under natural conditions, most birds lay only until a clutch is complete, and they will then incubate all the eggs. Hens are then said to "go broody". The broody hen will stop laying and instead will focus on the incubation of the eggs (a full clutch is usually about 12 eggs). She will "sit" or "set" on the nest, protesting or pecking in defense if disturbed or removed, and she will rarely leave the nest to eat, drink, or dust-bathe. While brooding, the hen maintains the nest at a constant temperature and humidity, as well as turning the eggs regularly during the first part of the incubation. To stimulate broodiness, owners may place several artificial eggs in the nest. To discourage it, they may place the hen in an elevated cage with an open wire floor.

Breeds artificially developed for egg production rarely go broody, and those that do often stop part-way through the incubation. However, other breeds, such as the Cochin, Cornish and Silkie, do regularly go broody, and they make excellent mothers, not only for chicken eggs but also for those of other species — even those with much smaller or larger eggs and different incubation periods, such as quail, pheasants, turkeys, or geese.

Hatching and early life

Fertile chicken eggs hatch at the end of the incubation period, about 21 days.[23] Development of the chick starts only when incubation begins, so all chicks hatch within a day or two of each other, despite perhaps being laid over a period of two weeks or so. Before hatching, the hen can hear the chicks peeping inside the eggs, and will gently cluck to stimulate them to break out of their shells. The chick begins by "pipping"; pecking a breathing hole with its egg tooth towards the blunt end of the egg, usually on the upper side. The chick then rests for some hours, absorbing the remaining egg yolk and withdrawing the blood supply from the membrane beneath the shell (used earlier for breathing through the shell). The chick then enlarges the hole, gradually turning round as it goes, and eventually severing the blunt end of the shell completely to make a lid. The chick crawls out of the remaining shell, and the wet down dries out in the warmth of the nest.

Hens usually remain on the nest for about two days after the first chick hatches, and during this time the newly hatched chicks feed by absorbing the internal yolk sac. Some breeds sometimes start eating cracked eggs, which can become habitual.[26] Hens fiercely guard their chicks, and brood them when necessary to keep them warm, at first often returning to the nest at night. She leads them to food and water and will call them toward edible items, but seldom feeds them directly. She continues to care for them until they are several weeks old. Although there are some hens, the Black Hen Atriana, in the territory of Atri, that are aggressive and often kill their own chicks. They are characterized as a small-sized hen that lays mant eggs daily.[27]

Defensive behaviour

Chickens may occasionally gang up on a weak or inexperienced predator. At least one credible report exists of a young fox killed by hens.[28][29][30] A group of hens have been recorded in attacking a hawk that had entered their coop.[31]

Embryology

.

In 2006, scientists researching the ancestry of birds "turned on" a chicken recessive gene, talpid2, and found that the embryo jaws initiated formation of teeth, like those found in ancient bird fossils. John Fallon, the overseer of the project, stated that chickens have "...retained the ability to make teeth, under certain conditions... ."[32]

Breeding

Origins

Galliformes, the order of bird that chickens belong to, is directly linked to the survival of birds when all other dinosaurs went extinct. Water or ground-dwelling fowl, similar to modern partridges, survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event that killed all tree-dwelling birds and dinosaurs.[33] Some of these evolved into the modern galliformes, of which domesticated chickens are a main model. They are descended primarily from the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) and are scientifically classified as the same species.[34] As such, they can and do freely interbreed with populations of red junglefowl.[34] Subsequent hybridization of domestic chicken with grey junglefowl, Sri Lankan junglefowl and green junglefowl occurred[35] with at least, a gene for yellow skin was incorporated into domestic birds through hybridization with the grey junglefowl (G. sonneratii).[36] In a study published in 2020, it was found that chickens shared between 71% - 79% of their genome with red junglefowl with domestication period dated to 8,000 years ago.[35]

The traditional view is that chickens were first domesticated for cockfighting in Asia, Africa, and Europe.[3] In the last decade, there have been a number of genetic studies to clarify the origins. According to one early study, a single domestication event which took place in what now is the country of Thailand gave rise to the modern chicken with minor transitions separating the modern breeds.[37] However, that study was later found to be based on incomplete data, and recent studies point to multiple maternal origins, with the clade found in the Americas, Europe, Middle East, and Africa, originating from the Indian subcontinent, where a large number of unique haplotypes occur.[38][39] The red junglefowl, known as the bamboo fowl in many Southeast Asian languages, is a special bird well-adapted to take advantage of the large amounts of fruits that are produced during the end of the 50-year bamboo seeding cycle, to boost its own reproduction.[40] In domesticating the chicken, humans took advantage of this predisposition for prolific reproduction of the red junglefowl when exposed to large amounts of food.[41]

Several controversies still surround the time chicken was domesticated. A recent molecular evidence obtained from whole-genome study published in 2020 reveal that chicken was domesticated 8,000 years ago.[35] Though, it was previously thought to have been domesticated in Southern China in 6000 BC based on paleoclimatic assumptions[42] which has now raised doubts from another study that question whether those birds were the ancestors of chickens today.[43] Majority of the world chicken today may have migrated from the Harappan culture of the Indus Valley. Eventually, the chicken moved to the Tarim basin of central Asia. The chicken reached Europe (Romania, Turkey, Greece, Ukraine) about 3000 BC.[44] Introduction into Western Europe came far later, about the 1st millennium BC. Phoenicians spread chickens along the Mediterranean coasts as far as Iberia. Breeding increased under the Roman Empire, and was reduced in the Middle Ages.[44] Genetic sequencing of chicken bones from archaeological sites in Europe revealed that in the High Middle Ages chickens became less aggressive and began to lay eggs earlier in the breeding season.[45]

Middle East traces of chicken go back to a little earlier than 2000 BC, in Syria; chickens went southward only in the 1st millennium BC. They reached Egypt for purposes of cockfighting about 1400 BC, and became widely bred only in Ptolemaic Egypt (about 300 BC).[44] Little is known about the chicken's introduction into Africa. It was during the Hellenistic period (4th-2nd centuries BC), in the Southern Levant, that chickens began widely to be domesticated for food.[4] This change occurred at least 100 years before domestication of chickens spread to Europe.

Three possible routes of introduction in about the early first millennium AD could have been through the Egyptian Nile Valley, the East Africa Roman-Greek or Indian trade, or from Carthage and the Berbers, across the Sahara. The earliest known remains are from Mali, Nubia, East Coast, and South Africa and date back to the middle of the first millennium AD.[44]

Domestic chicken in the Americas before Western contact is still an ongoing discussion, but blue-egged chickens, found only in the Americas and Asia, suggest an Asian origin for early American chickens.[44]

A lack of data from Thailand, Russia, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa makes it difficult to lay out a clear map of the spread of chickens in these areas; better description and genetic analysis of local breeds threatened by extinction may also help with research into this area.[44]

South America

An unusual variety of chicken that has its origins in South America is the araucana, bred in southern Chile by the Mapuche people. Araucanas, some of which are tailless and some of which have tufts of feathers around their ears, lay blue-green eggs. It has long been suggested that they pre-date the arrival of European chickens brought by the Spanish and are evidence of pre-Columbian trans-Pacific contacts between Asian or Pacific Oceanic peoples, particularly the Polynesians, and South America. In 2007, an international team of researchers reported the results of analysis of chicken bones found on the Arauco Peninsula in south-central Chile. Radiocarbon dating suggested that the chickens were Pre-Columbian, and DNA analysis showed that they were related to prehistoric populations of chickens in Polynesia.[46] These results appeared to confirm that the chickens came from Polynesia and that there were transpacific contacts between Polynesia and South America before Columbus's arrival in the Americas.[47]

However, a later report looking at the same specimens concluded:

A published, apparently pre-Columbian, Chilean specimen and six pre-European Polynesian specimens also cluster with the same European/Indian subcontinental/Southeast Asian sequences, providing no support for a Polynesian introduction of chickens to South America. In contrast, sequences from two archaeological sites on Easter Island group with an uncommon haplogroup from Indonesia, Japan, and China and may represent a genetic signature of an early Polynesian dispersal. Modeling of the potential marine carbon contribution to the Chilean archaeological specimen casts further doubt on claims for pre-Columbian chickens, and definitive proof will require further analyses of ancient DNA sequences and radiocarbon and stable isotope data from archaeological excavations within both Chile and Polynesia.[48]

The debate for and against a Polynesian origin for South American chickens continued with this 2014 paper and subsequent responses in PNAS.[49]

Use by humans

Farming

More than 50 billion chickens are reared annually as a source of meat and eggs.[51] In the United States alone, more than 8 billion chickens are slaughtered each year for meat,[52] and more than 300 million chickens are reared for egg production.[53]

The vast majority of poultry are raised in factory farms. According to the Worldwatch Institute, 74 percent of the world's poultry meat and 68 percent of eggs are produced this way.[54] An alternative to intensive poultry farming is free-range farming.

Friction between these two main methods has led to long-term issues of ethical consumerism. Opponents of intensive farming argue that it harms the environment, creates human health risks and is inhumane.[55] Advocates of intensive farming say that their highly efficient systems save land and food resources owing to increased productivity, and that the animals are looked after in state-of-the-art environmentally controlled facilities.[56]

Reared for meat

Chickens farmed for meat are called broilers. Chickens will naturally live for six or more years, but broiler breeds typically take less than six weeks to reach slaughter size.[57] A free range or organic broiler will usually be slaughtered at about 14 weeks of age.

Reared for eggs

Chickens farmed primarily for eggs are called layer hens. In total, the UK alone consumes more than 34 million eggs per day.[58] Some hen breeds can produce over 300 eggs per year, with "the highest authenticated rate of egg laying being 371 eggs in 364 days".[59] After 12 months of laying, the commercial hen's egg-laying ability starts to decline to the point where the flock is commercially unviable. Hens, particularly from battery cage systems, are sometimes infirm or have lost a significant amount of their feathers, and their life expectancy has been reduced from around seven years to less than two years.[60] In the UK and Europe, laying hens are then slaughtered and used in processed foods or sold as "soup hens".[60] In some other countries, flocks are sometimes force moulted, rather than being slaughtered, to re-invigorate egg-laying. This involves complete withdrawal of food (and sometimes water) for 7–14 days[61] or sufficiently long to cause a body weight loss of 25 to 35%,[62] or up to 28 days under experimental conditions.[63] This stimulates the hen to lose her feathers, but also re-invigorates egg-production. Some flocks may be force-moulted several times. In 2003, more than 75% of all flocks were moulted in the US.[64]

As pets

Keeping chickens as pets became increasingly popular in the 2000s[65] among urban and suburban residents.[66] Many people obtain chickens for their egg production but often name them and treat them as any other pet. Chickens are just like any other pet in that they provide companionship and have individual personalities. While many do not cuddle much, they will eat from one's hand, respond to and follow their handlers, as well as show affection.[67]

Chickens are social, inquisitive, intelligent birds, and many find their behaviour entertaining.[68] Certain breeds, such as Silkies and many bantam varieties, are generally docile and are often recommended as good pets around children with disabilities.[69] Many people feed chickens in part with kitchen food scraps.

Chickens can carry and transmit salmonella in their dander and feces. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advise against bringing them indoors or letting small children handle them.[70][71]

Artificial incubation

Incubation can successfully occur artificially in machines that provide the correct, controlled environment for the developing chick.[72][73] The average incubation period for chickens is 21 days but may depend on the temperature and humidity in the incubator. Temperature regulation is the most critical factor for a successful hatch. Variations of more than 1 °C (1.8 °F) from the optimum temperature of 37.5 °C (99.5 °F) will reduce hatch rates. Humidity is also important because the rate at which eggs lose water by evaporation depends on the ambient relative humidity. Evaporation can be assessed by candling, to view the size of the air sac, or by measuring weight loss. Relative humidity should be increased to around 70% in the last three days of incubation to keep the membrane around the hatching chick from drying out after the chick cracks the shell. Lower humidity is usual in the first 18 days to ensure adequate evaporation. The position of the eggs in the incubator can also influence hatch rates. For best results, eggs should be placed with the pointed ends down and turned regularly (at least three times per day) until one to three days before hatching. If the eggs aren't turned, the embryo inside may stick to the shell and may hatch with physical defects. Adequate ventilation is necessary to provide the embryo with oxygen. Older eggs require increased ventilation.

Many commercial incubators are industrial-sized with shelves holding tens of thousands of eggs at a time, with rotation of the eggs a fully automated process. Home incubators are boxes holding from 6 to 75 eggs; they are usually electrically powered, but in the past some were heated with an oil or paraffin lamp.

Diseases and ailments

Chickens are susceptible to several parasites, including lice, mites, ticks, fleas, and intestinal worms, as well as other diseases. Despite the name, they are not affected by chickenpox, which is generally restricted to humans.[74]

Some of the diseases that can affect chickens are shown below:

| Name | Common name | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillosis | Aspergillus fungi | |

| Avian influenza | bird flu | virus |

| Histomoniasis | blackhead disease | Histomonas meleagridis |

| Botulism | paralysis | Clostridium botulinum toxin |

| Cage layer fatigue | mineral deficiency, lack of physical exercise | |

| Campylobacteriosis | tissue injury in the gut | |

| Coccidiosis | Coccidia | |

| Colds | virus | |

| Crop bound | improper feeding | |

| Dermanyssus gallinae | red mite | parasite |

| Egg binding | oversized egg | |

| Erysipelas | Streptococcus bacteria | |

| Fatty liver hemorrhagic syndrome | high-energy food | |

| Fowl cholera | Pasteurella multocida | |

| Fowlpox | Fowlpox virus | |

| Fowl typhoid | bacteria | |

| Avian infectious laryngotracheitis | LT | Gallid alphaherpesvirus 1 |

| Gapeworm | Syngamus trachea | worms |

| Infectious bronchitis | Infectious Bronchitis Virus | |

| Infectious bursal disease | Gumboro | infectious bursal disease virus |

| Infectious coryza in chickens | Avibacterium paragallinarum | |

| Lymphoid leukosis | Avian sarcoma leukosis virus | |

| Marek's disease | Gallid alphaherpesvirus 2 | |

| Moniliasis | yeast infection or thrush |

Candida fungi |

| Mycoplasma | bacteria | |

| Newcastle disease | Avian avulavirus 1 | |

| Necrotic enteritis | bacteria | |

| Omphalitis | Mushy chick disease[75] | bacteria |

| Peritonitis[76] | infection in abdomen from egg yolk | |

| Psittacosis | Chlamydia psittaci | |

| Pullorum | Salmonella | bacteria |

| Scaly leg | Cnemidocoptes mutans | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | cancer | |

| Tibial dyschondroplasia | speed growing | |

| Toxoplasmosis | Toxoplasma gondii | |

| Ulcerative enteritis | bacteria | |

| Ulcerative pododermatitis | bumblefoot | bacteria |

In religion and mythology

Since antiquity chickens have been, and still are, a sacred animal in some cultures[77] and deeply embedded within belief systems and religious worship. The term "Persian bird" for the rooster appears to have been given by the Greeks after Persian contact "because of his great importance and his religious use among the Persians".[78]

In Indonesia the chicken has great significance during the Hindu cremation ceremony. A chicken is considered a channel for evil spirits which may be present during the ceremony. A chicken is tethered by the leg and kept present at the ceremony for its duration to ensure that any evil spirits present go into the chicken and not the family members. The chicken is then taken home and returns to its normal life.

In ancient Greece, chickens were not normally used for sacrifices, perhaps because they were still considered an exotic animal. Because of its valor, the cock is found as an attribute of Ares, Heracles, and Athena. The alleged last words of Socrates as he died from hemlock poisoning, as recounted by Plato, were "Crito, I owe a cock to Asclepius; will you remember to pay the debt?", signifying that death was a cure for the illness of life.

The Greeks believed that even lions were afraid of roosters. Several of Aesop's Fables reference this belief.

In the New Testament, Jesus prophesied the betrayal by Peter: "Jesus answered, 'I tell you, Peter, before the rooster crows today, you will deny three times that you know me.'"[79] It happened,[80] and Peter cried bitterly. This made the rooster a symbol for both vigilance and betrayal.

Earlier, Jesus compares himself to a mother hen when talking about Jerusalem: "O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, you who kill the prophets and stone those sent to you, how often I have longed to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, but you were not willing."[81]

In the sixth century, Pope Gregory I declared the rooster the emblem of Christianity[82] and another Papal enactment of the ninth century by Pope Nicholas I[77] ordered the figure of the rooster to be placed on every church steeple.[83]

In many Central European folk tales, the devil is believed to flee at the first crowing of a rooster.

In traditional Jewish practice, a kosher animal is swung around the head and then slaughtered on the afternoon before Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, in a ritual called kapparos; it is now common practice to cradle the bird and move him or her around the head. A chicken or fish is typically used because it is commonly available (and small enough to hold). The sacrifice of the animal is to receive atonement, for the animal symbolically takes on all the person's sins in kapparos. The meat is then donated to the poor. A woman brings a hen for the ceremony, while a man brings a rooster. Although not a sacrifice in the biblical sense, the death of the animal reminds the penitent sinner that his or her life is in God's hands.

The Talmud speaks of learning "courtesy toward one's mate" from the rooster.[84] This might refer to the fact that when a rooster finds something good to eat, he calls his hens to eat first. A rooster might also come to the aid of a hen if she is attacked. The Talmud likewise provides us with the statement "Had the Torah not been given to us, we would have learned modesty from cats, honest toil from ants, chastity from doves and gallantry from cocks",[85][86] which may be further understood as to that of the gallantry of cocks being taken in the context of a religious instilling vessel of "a girt one of the loins" (Young's Literal Translation) that which is "stately in his stride" and "move with stately bearing" in the Book of Proverbs 30:29-31 as referenced by Michael V. Fox in his Proverbs 10-31 where Saʻadiah ben Yosef Gaon (Saadia Gaon) identifies the definitive trait of "A cock girded about the loins" in Proverbs 30:31 (Douay–Rheims Bible) as "the honesty of their behavior and their success",[87] identifying a spiritual purpose of a religious vessel within that religious instilling schema of purpose and use.

The chicken is one of the symbols of the Chinese Zodiac. In Chinese folk religion, a cooked chicken as a religious offering is usually limited to ancestor veneration and worship of village deities. Vegetarian deities such as the Buddha are not recipients of such offerings. Under some observations, an offering of chicken is presented with "serious" prayer (while roasted pork is offered during a joyous celebration). In Confucian Chinese weddings, a chicken can be used as a substitute for one who is seriously ill or not available (e.g., sudden death) to attend the ceremony. A red silk scarf is placed on the chicken's head and a close relative of the absent bride/groom holds the chicken so the ceremony may proceed. However, this practice is rare today.

A cockatrice was supposed to have been born from an egg laid by a rooster, as well as killed by a rooster's call.

In history

An early domestication of chickens in Southeast Asia is probable, since the word for domestic chicken (*manuk) is part of the reconstructed Proto-Austronesian language . Chickens, together with dogs and pigs, were the domestic animals of the Lapita culture,[88] the first Neolithic culture of Oceania.[89]

The first pictures of chickens in Europe are found on Corinthian pottery of the 7th century BC.[90][91] The poet Cratinus (mid-5th century BC, according to the later Greek author Athenaeus) calls the chicken "the Persian alarm". In Aristophanes's comedy The Birds (414 BC) a chicken is called "the Median bird", which points to an introduction from the East. Pictures of chickens are found on Greek red figure and black-figure pottery.

In ancient Greece, chickens were still rare and were a rather prestigious food for symposia.[92] Delos seems to have been a center of chicken breeding (Columella, De Re Rustica 8.3.4). "About 3200 BC chickens were common in Sindh. After the attacks of Aria people these fowls spred from Sindh to Balakh and Iran. During attacks and wars between Iranian and Greeks the chickens of Hellanic breed came in Iran and about 1000 BC Hellanic chickens came into Sindh through Medan".[93]

The Romans used chickens for oracles, both when flying ("ex avibus", Augury) and when feeding ("auspicium ex tripudiis", Alectryomancy). The hen ("gallina") gave a favourable omen ("auspicium ratum"), when appearing from the left (Cic., de Div. ii.26), like the crow and the owl.

For the oracle "ex tripudiis" according to Cicero (Cic. de Div. ii.34), any bird could be used in auspice, and shows at one point that any bird could perform the tripudium[94] but normally only chickens ("pulli") were consulted. The chickens were cared for by the pullarius, who opened their cage and fed them pulses or a special kind of soft cake when an augury was needed. If the chickens stayed in their cage, made noises ("occinerent"), beat their wings or flew away, the omen was bad; if they ate greedily, the omen was good.[95]

In 249 BC, the Roman general Publius Claudius Pulcher had his "sacred chickens" "[96] thrown overboard when they refused to feed before the battle of Drepana, saying "If they won't eat, perhaps they will drink." He promptly lost the battle against the Carthaginians and 93 Roman ships were sunk. Back in Rome, he was tried for impiety and heavily fined.[97]

In 162 BC, the Lex Faunia forbade fattening hens on grain which was a measure enacted to reduce the demand for grain.[98] To get around this, the Romans castrated roosters (capon), which resulted in a doubling of size[99] despite the law that was passed in Rome that forbade the consumption of fattened chickens. It was renewed a number of times, but does not seem to have been successful. Fattening chickens with bread soaked in milk was thought to give especially delicious results. The Roman gourmet Apicius offers 17 recipes for chicken, mainly boiled chicken with a sauce. All parts of the animal are used: the recipes include the stomach, liver, testicles and even the pygostyle (the fatty "tail" of the chicken where the tail feathers attach).

The Roman author Columella gives advice on chicken breeding in the eighth book of his treatise, De Re Rustica (On Agriculture). He identified Tanagrian, Rhodic, Chalkidic and Median (commonly misidentified as Melian) breeds, which have an impressive appearance, a quarrelsome nature and were used for cockfighting by the Greeks (De Re Rustica 8.3.4). For farming, native (Roman) chickens are to be preferred, or a cross between native hens and Greek cocks (De Re Rustica 8.2.13). Dwarf chickens are nice to watch because of their size but have no other advantages.

According to Columella (De Re Rustica 8.2.7), the ideal flock consists of 200 birds, which can be supervised by one person if someone is watching for stray animals. White chickens should be avoided as they are not very fertile and are easily caught by eagles or goshawks. One cock should be kept for five hens. In the case of Rhodian and Median cocks that are very heavy and therefore not much inclined to sex, only three hens are kept per cock. The hens of heavy fowls are not much inclined to brood; therefore their eggs are best hatched by normal hens. A hen can hatch no more than 15-23 eggs, depending on the time of year, and supervise no more than 30 hatchlings. Eggs that are long and pointed give more male hatchlings, rounded eggs mainly female hatchlings (De Re Rustica 8.5.11).

Columella also states that chicken coops should face southeast and lie adjacent to the kitchen, as smoke is beneficial for the animals and "poultry never thrive so well as in warmth and smoke" (De Re Rustica 8.3.1).[100] Coops should consist of three rooms and possess a hearth. Dry dust or ash should be provided for dust-baths.

According to Columella (De Re Rustica 8.4.1), chickens should be fed on barley groats, small chick-peas, millet and wheat bran, if they are cheap. Wheat itself should be avoided as it is harmful to the birds. Boiled ryegrass (Lolium sp.) and the leaves and seeds of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) can be used as well. Grape marc can be used, but only when the hens stop laying eggs, that is, about the middle of November; otherwise eggs are small and few. When feeding grape marc, it should be supplemented with some bran. Hens start to lay eggs after the winter solstice, in warm places around the first of January, in colder areas in the middle of February. Parboiled barley increases their fertility; this should be mixed with alfalfa leaves and seeds, or vetches or millet if alfalfa is not at hand. Free-ranging chickens should receive two cups of barley daily.

Columella[101] advises farmers to slaughter hens that are older than three years, those that aren't productive or are poor care-takers of their eggs, and particularly those that eat their own and other hens' eggs.

According to Aldrovandi, capons were produced by burning "the hind part of the bowels, or loins or spurs"[102] with a hot iron. The wound was treated with potter's chalk.

For the use of poultry and eggs in the kitchens of ancient Rome see Roman eating and drinking.

Chickens were spread by Polynesian seafarers and reached Easter Island in the 12th century AD, where they were the only domestic animal, with the possible exception of the Polynesian rat (Rattus exulans). They were housed in extremely solid chicken coops built from stone, which was first reported as such to Linton Palmer in 1868, who also "expressed his doubts about this".[103].

See also

- Urban chicken keeping

- Abnormal behaviour of birds in captivity

- Battery Hen Welfare Trust, a UK charity for laying hens

- Chicken eyeglasses

- Chicken fat

- Chicken hypnotism

- Chicken or the egg

- Chicken manure

- Chook raffle – a type of raffle where the prize is a chicken.

- Early feeding

- Feral chicken

- Gamebird hybrids – hybrids between chickens, peafowl, guineafowl and pheasants

- Henopause

- List of chicken breeds

- Poularde

- Rubber chicken

- Sex change in chickens

- Symbolic chickens

- Tastes like chicken

- Unihemispheric slow-wave sleep

- "Why did the chicken cross the road?"

References

- "Number of chickens worldwide from 1990 to 2018". Statista. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation (July 2011). "Global Livestock Counts". The Economist. Archived from the original on July 15, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- "The Ancient City Where People Decided to Eat Chickens". Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Perry-Gal, Lee; Erlich, Adi; Gilboa, Ayelet; Bar-Oz, Guy (2015). "Earliest economic exploitation of chicken outside East Asia: Evidence from the Hellenistic Southern Levant". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (32): 9849–9854. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.9849P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1504236112. PMC 4538678. PMID 26195775. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Xiang, H.; Gao, J.; Yu, B.; Zhou, H.; Cai, D.; Zhang, Y. & Zhao, X. (2014). "Early Holocene chicken domestication in northern China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (49): 17564–69. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11117564X. doi:10.1073/pnas.1411882111. PMC 4267363. PMID 25422439.

- Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, (Anthea Bell, translator) The History of Food, Ch. 11 "The History of Poultry", revised ed. 2009, p. 306.

- Carter, Howard (April 1923). "An Ostracon Depicting a Red Jungle-Fowl (The Earliest Known Drawing of the Domestic Cock)". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 9 (1/2): 1–4. doi:10.2307/3853489. JSTOR 3853489.

- Pritchard, Earl H. "The Asiatic Campaigns of Thutmose III". Ancient Near East Texts related to the Old Testament. p. 240.

- Roehrig, Catharine H.; Dreyfus, Renée; Keller, Cathleen A. (2005). Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 268. ISBN 978-1-58839-173-5. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- Cockerel. Dictionary.reference.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- Pullet. Dictionary.reference.com. Archived from the original on November 9, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- Definition of "chook". Encarta. Archived from the original on April 9, 2009.

an offensive term that deliberately insults a woman's age or appearance (slang)

- Dohner, Janet Vorwald (January 1, 2001). The Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300138139. Archived from the original on June 28, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- Berhardt, Clyde E. B. (1986). I Remember: Eighty Years of Black Entertainment, Big Bands. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8122-8018-0. OCLC 12805260.

- "Info on Chicken Care". Ideas-4-pets.co.uk. 2003. Archived from the original on June 25, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- D Lines (July 27, 2013). "Chicken Kills Rattlesnake". YouTube. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- Gerard P.Worrell AKA "Farmer Jerry". "Frequently asked questions about chickens & eggs". Gworrell.freeyellow.com. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- "The Poultry Guide – A to Z and FAQs". Ruleworks.co.uk. Archived from the original on November 28, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- Smith, Jamon (August 6, 2006). "World's oldest chicken starred in magic shows, was on 'Tonight Show'". Tuscaloosa News. Alabama, USA. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- "Introducing new hens to a flock " Musings from a Stonehead". Stonehead.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- "Top cock: Roosters crow in pecking order". Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- Evans, Christopher S.; Evans, Linda; Marler, Peter (July 1, 1993). "On the meaning of alarm calls: functional reference in an avian vocal system". Animal Behaviour. 46 (1): 23–38. doi:10.1006/anbe.1993.1158. ISSN 0003-3472.

- Grandin, Temple; Johnson, Catherine (2005). Animals in Translation. New York City: Scribner. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-7432-4769-6.

- Cheng, Kimberly M. and Burns, Jeffrey T. (1988). "Dominance relationship and mating behavior of domestic cocks--a model to study mate-guarding and sperm competition in birds" (PDF). The Condor. 90 (3): 697–704. doi:10.2307/1368360. JSTOR 1368360.

- Sherwin, C.M.; Nicol, C.J. (1993). "Factors influencing floor-laying by hens in modified cages". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 36 (2–3): 211–222. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(93)90011-d.

- Ali, A.; Cheng, K.M. (1985). "Early egg production in genetically blind (rc/rc) chickens in comparison with sighted (Rc+/rc) controls". Poultry Science. 64 (5): 789–794. doi:10.3382/ps.0640789. PMID 4001066.

- Gessner, Conrad (January 8, 2010) [c. 1555]. De Gallo Gallinaceo, et iis Omnibus [The Chicken of Conrad Gessner]. Translated by Corti, Elio. transcribed by Fernando Civardi. pp. 4–5.

- "Chickens team up to 'peck fox to death'". The Independent. March 13, 2019. Archived from the original on March 15, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- "Chickens 'gang up' to kill fox". Bbc.co.uk. March 13, 2019. Archived from the original on March 14, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- AFP (March 12, 2019). "Chickens 'teamed up to kill fox' at Brittany farming school". Theguardian.com. Archived from the original on March 13, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- "Check this out! This hawk thought he'd have a chicken dinner until he met our hens". Rustic Road Farm – via Facebook.

- Scientists Find Chickens Retain Ancient Ability to Grow Teeth Archived June 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Ammu Kannampilly, ABC News, February 27, 2006. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- "Quaillike creatures were the only birds to survive the dinosaur-killing asteroid impact". May 24, 2018. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- Wong, GK; et al. (December 2004). "A genetic variation map for chicken with 2.8 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms". Nature. 432 (7018): 717–722. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..717B. doi:10.1038/nature03156. PMC 2263125. PMID 15592405.

- Lawal, RA.; et al. (2020). "The wild species genome ancestry of domestic chickens". BMC Biology. 18 (13): 13. doi:10.1186/s12915-020-0738-1. PMC 7014787. PMID 32050971.

- Eriksson, J; Larson, G; Gunnarsson, U; Bed'hom, B; Tixier-Boichard, M; et al. (2008). "Identification of the Yellow Skin Gene Reveals a Hybrid Origin of the Domestic Chicken". PLOS Genet. 4 (2): e1000010. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000010. PMC 2265484. PMID 18454198.

- Fumihito, A; Miyake, T; Sumi, S; Takada, M; Ohno, S; Kondo, N (December 20, 1994), "One subspecies of the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus gallus) suffices as the matriarchic ancestor of all domestic breeds", PNAS, 91 (26): 12505–12509, Bibcode:1994PNAS...9112505F, doi:10.1073/pnas.91.26.12505, PMC 45467, PMID 7809067

- Liu, Yi-Ping; Wu, Gui-Sheng; Yao, Yong-Gang; Miao, Yong-Wang; Luikart, Gordon; Baig, Mumtaz; Beja-Pereira, Albano; Ding, Zhao-Li; Palanichamy, Malliya Gounder; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2006), "Multiple maternal origins of chickens: Out of the Asian jungles", Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 38 (1): 12–19, doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.014, PMID 16275023

- Zeder; et al. (2006). "Documenting domestication: the intersection of genetics and archaeology". Trends in Genetics. 22 (3): 139–155. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2006.01.007. PMID 16458995.

- King, Rick (February 24, 2009), "Rat Attack", NOVA and National Geographic Television, archived from the original on August 23, 2017, retrieved August 25, 2017

- King, Rick (February 1, 2009), "Plant vs. Predator", NOVA, archived from the original on August 21, 2017, retrieved August 25, 2017

- West, B.; Zhou, B.X. (1988). "Did chickens go north? New evidence for domestication". J. Archaeol. Sci. 14 (5): 515–533. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(88)90080-5.

- Al-Nasser, A.; et al. (2007). "Overview of chicken taxonomy and domestication". World's Poultry Science Journal. 63 (2): 285–300. doi:10.1017/S004393390700147X.

- CHOF : The Cambridge History of Food, 2000, Cambridge University Press, vol.1, pp496-499

- Brown, Marley (September–October 2017). "Fast Food". Archaeology. 70 (5): 18. ISSN 0003-8113. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- DNA reveals how the chicken crossed the sea Archived October 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Brendan Borrell, Nature, June 5, 2007. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- A. A. Storey et al., "Radiocarbon and DNA evidence for a pre-Columbian introduction of Polynesian chickens to Chile", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0703993104; John Noble Wilford, "First Chickens in Americas were Brought from Polynesia, The New York Times, June 5, 2007.

- Gongora, Jaime; Rawlence, Nicolas J.; Mobegi, Victor A.; Jianlin, Han; Alcalde, Jose A.; Matus, Jose T.; Hanotte, Olivier; Moran, Chris; Austin, J.; Ulm, Sean; Anderson, Atholl J.; Larson, Greger; Cooper, Alan (2008). "Indo-European and Asian origins for Chilean and Pacific chickens revealed by mtDNA". PNAS. 105 (30): 10308–10313. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10510308G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801991105. PMC 2492461. PMID 18663216.

- Thomson, Vicki A.; Lebrasseur, Ophélie; Austin, Jeremy J.; Hunt, Terry L.; Burney, David A.; Denham, Tim; Rawlence, Nicolas J.; Wood, Jamie R.; Gongora, Jaime; Girdland Flink, Linus; Linderholm, Anna; Dobney, Keith; Larson, Greger; Cooper, Alan (2014). "Using ancient DNA to study the origins and dispersal of ancestral Polynesian chickens across the Pacific". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (13): 4826–4831. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4826T. doi:10.1073/pnas.1320412111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3977275. PMID 24639505.

- Jones, E.K.M.; Prescott, N.B. (2000). "Visual cues used in the choice of mate by fowl and their potential importance for the breeder industry". World's Poultry Science Journal. 56 (2): 127–138. doi:10.1079/WPS20000010.

- "About chickens | Compassion in World Farming". Ciwf.org.uk. Archived from the original on April 26, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Fereira, John. "Poultry Slaughter Annual Summary". usda.mannlib.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on April 26, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Fereira, John. "Chickens and Eggs Annual Summary". usda.mannlib.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on April 26, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- "Towards Happier Meals In A Globalized World". World Watch Institute. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- Ilea, Ramona Cristina (April 1, 2009). "Intensive Livestock Farming: Global Trends, Increased Environmental Concerns, and Ethical Solutions". Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. 22 (2): 153–167. doi:10.1007/s10806-008-9136-3. ISSN 1187-7863.

- Tilman, David; Cassman, Kenneth G.; Matson, Pamela A.; Naylor, Rosamond; Polasky, Stephen (August 8, 2002). "Agricultural sustainability and intensive production practices". Nature. 418 (6898): 671–677. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..671T. doi:10.1038/nature01014. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 12167873.

- "Broiler Chickens Fact Sheet // Animals Australia". Animalsaustralia.org. Archived from the original on July 12, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- "UK Egg Industry Data | Official Egg Info". Egginfo.co.uk. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Guinness World Records 2011 ed. by Craig Glenday – page 286

- Browne, Anthony (March 10, 2002). "Ten weeks to live". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- Patwardhan, D.; King, A. (2011). "Review: feed withdrawal and non feed withdrawal moult". World's Poultry Science Journal. 67 (2): 253–268. doi:10.1017/s0043933911000286.

- Webster, A.B. (2003). "Physiology and behavior of the hen during induced moult". Poultry Science. 82 (6): 992–1002. doi:10.1093/ps/82.6.992. PMID 12817455.

- Molino, A.B.; Garcia, E.A.; Berto, D.A.; Pelícia, K.; Silva, A.P.; Vercese, F. (2009). "The Effects of Alternative Forced-Molting Methods on The Performance and Egg Quality of Commercial Layers". Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science. 11 (2): 109–113. doi:10.1590/s1516-635x2009000200006.

- Yousaf, M.; Chaudhry, A.S. (2008). "History, changing scenarios and future strategies to induce moulting in laying hens". World's Poultry Science Journal. 64: 65–75. doi:10.1017/s0043933907001729.

- Fly, Colin (July 27, 2007). "Some homeowners find chickens all the rage". Chicago Tribune.

- Pollack-Fusi, Mindy (December 16, 2004). "Cooped up in suburbia". Boston Globe.

- Boone, Lisa. "Chickens will become a beloved pet — just like the family dog". latimes.com. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- United Poultry Concerns. "Providing a Good Home for Chickens". Archived from the original on June 5, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2009.

- "Choosing Your Chickens". Clucks and Chooks. Archived from the original on July 30, 2009.

- "Forget dogs and cats. The most pampered pets of the moment might be our backyard chickens". USA TODAY. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- CDC (March 18, 2019). "Keeping Backyard Poultry". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- Joe G. Berry. "Artificial Incubation". Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service, Oklahoma State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 4, 2010. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- Phillip J. Clauer. "Incubating Eggs" (PDF). Virginia Cooperative Extension Service, Virginia State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- White, T. M.; Gilden, D. H.; Mahalingam, R. (2001). "An animal model of varicella virus infection". Brain Pathology (Zurich, Switzerland). 11 (4): 475–479. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2001.tb00416.x. PMID 11556693.

- "Overview of Omphalitis in Poultry". Merck Veterinary Manual. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- "Clucks and Chooks: guide to keeping chickens". Henkeeping.co.uk. Archived from the original on January 15, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- Adler, Jerry; Lawler, Andrew (June 2012). "How the Chicken Conquered the World". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- Peters, John P. (1913). "The Cock". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 33: 363–396. doi:10.2307/592841. JSTOR 592841. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- Luke 22:34

- Luke 22:61

- Matthew 23:37; also Luke 13:34. For a recent study of chickens in the New Testament, see Joshua N. Tilton "Chickens and the Cultural Context of the Gospels Archived August 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine" www.jerusalemperspective.com Archived August 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- The Antiquary: a magazine devoted to the study of the past, Volume 17 edited by Edward Walford, John Charles Cox, George Latimer Apperson – page 202

- The Philadelphia Museum bulletin, Volumes 1-5, Pennsylvania Museum of Art, Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art, p 14, 1906

- Eruvin 100b.

- A Treasury of Jewish Quotations By Joseph L. Baron – 1985

- Jonathan ben Nappaha. Talmud: Erubin 100b

- PROVERBS 10-31, Volume 18, Michael V. Fox, Yale University Press 2009, 704 pages

- Meleisea, Malama (March 25, 2004). The Cambridge History of the Pacific Islanders. Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780521003544. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- Crawford, Michael H. (March 13, 2019). Anthropological Genetics: Theory, Methods and Applications. Cambridge University Press. p. 411. ISBN 9780521546973. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- Karayanis, Dean; Karayanis, Catherine (March 13, 2019). Regional Greek Cooking. Hippocrene Books. p. 176. ISBN 9780781811460. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- Chiffolo, Anthony F.; Hesse, Rayner W. (March 13, 2019). Cooking with the Bible: Biblical Food, Feasts, and Lore. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 207. ISBN 9780313334108. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- Columella, Lucius Junius Moderatus (1941). On agriculture, with a recension of the text and an English translation by Harrison Boyd Ash. Robarts - University of Toronto. Cambridge Harvard University Press. p. 355. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- Marely A.Jull; Poultry Husbandry, chapter I,pages2-3; New York,1938

- A classical and archaeological dictionary of the manners, customs, laws, institutions, arts, etc. of the celebrated nations of antiquity, and of the middle ages: To which is prefixed A synoptical and chronological view of ancient history Archived June 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine P. Austin Nuttall – Printed for Whittaker and co., 1840 – page 601

- ltd, Chambers W. and R. (March 13, 2019). "Chambers's information for the people, ed. by W. and R. Chambers". p. 458. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- McKeown, J. C. (June 1, 2010). A Cabinet of Roman Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the World's Greatest Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780199752782. Archived from the original on September 12, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- Paul Sheridan (November 8, 2015). "The Sacred Chickens of Rome". Anecdotesfromantiquity.net. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne (March 25, 2009). A History of Food. John Wiley & Sons. p. 305. ISBN 9781444305142. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, (Anthea Bell, translator) The History of Food, Ch. 11 "The History of Poultry", revised ed. 2009, p. 305.

- "The New England Farmer". Thomas W. Shepard. March 13, 2019. p. 69. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ES Forster, EH Heffner (1954). On agriculture, volume II: books 5–9. The Loeb Classical Library: Harvard University Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-0674994485.

- Birkhead, Tim (March 13, 2019). The Wisdom of Birds: An Illustrated History of Ornithology. Bloomsbury. p. 278. ISBN 9780747598220. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- Flenley, John; Bahn, Paul (May 29, 2003). The Enigmas of Easter Island. Oxford University Press, UK. p. 6. ISBN 9780191587917. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

Further reading

- Green-Armytage, Stephen (October 2000). Extraordinary Chickens. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-3343-9.

- Smith, Page; Charles Daniel (April 2000). The Chicken Book. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-2213-1.

- Siddharth, Biswas (2014). "Gallus gallus domesticus Linnaeus, 1758: Keep safe your domestic fowl from your domestic foul" (PDF). Ambient Science. 1 (1): 41–43. doi:10.21276/ambi.2014.01.1.nn02. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- Andrew Lawler (2014). Why Did the Chicken Cross the World?: The Epic Saga of the Bird that Powers Civilization. Atria Books. ISBN 978-1476729893.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chickens. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Gallus gallus domesticus |