Megarachne

Megarachne is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Megarachne have been discovered in deposits of Late Carboniferous age, from the Gzhelian stage, in San Luis, Argentina. The fossils of the single and type species M. servinei have been recovered from deposits that had once been a freshwater environment. The generic name, composed of the Ancient Greek μέγας (megas) meaning "great" and Ancient Greek ἀράχνη (arachne) meaning "spider", translates to "great spider", because the fossil was misidentified as a large prehistoric spider.

| Megarachne | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cast of the holotype specimen of Megarachne exhibited at Royal Ontario Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Order: | †Eurypterida |

| Superfamily: | †Mycteropoidea |

| Family: | †Mycteroptidae |

| Genus: | †Megarachne Hünicken, 1980 |

| Species: | †M. servinei |

| Binomial name | |

| †Megarachne servinei Hünicken, 1980 | |

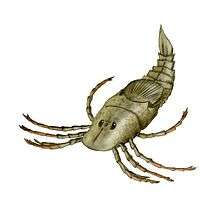

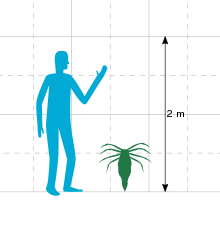

With a body length of 54 cm (21 in), Megarachne was a medium-sized eurypterid. If the original identification as a spider had been correct, Megarachne would have been the largest known spider to have ever lived. Eurypterids such as Megarachne are often called "sea scorpions", but the strata in which Megarachne has been found indicates that it dwelled in freshwater and not in marine environments.

Megarachne was similar to other eurypterids within the Mycteropoidea, a rare group known primarily from South Africa and Scotland. The mycteropoids had evolved a specialized method of feeding referred to as sweep-feeding. This involved raking through the substrate of riverbeds in order to capture and eat smaller invertebrates. Despite only two specimens having been recovered, Megarachne represents the most complete eurypterid discovered in Carboniferous deposits in South America so far.[1] Due to their fragmentary fossil record and similarities between the genera, some researchers have hypothesized that Megarachne and two other members of its family, Mycterops and Woodwardopterus, represent different developmental stages of a single genus.

Description

Known fossils of Megarachne indicate a body length of 54 cm (21 in). Whilst large for an arthropod, Megarachne was dwarfed by other eurypterids, even relatively close relatives such as Hibbertopterus which could reach lengths exceeding 1.5 m (59 in).[2] Though originally described as a giant spider, a multitude of features support the classification of Megarachne as a eurypterid. Among them, the raised lunules (the vaguely moon-shaped ornamentation, similar to scales) and the cuticular sculpture of the mucrones (a dividing ridge continuing uninterrupted throughout the carapace, the part of the exoskeleton which covers the head) are especially important since these features are characteristic of eurypterids.[3]

Megarachne possessed blade-like structures on its appendages (limbs) which would have allowed it to engage in a feeding method known as sweep-feeding, raking through the soft sediment of aquatic environments in swamps and rivers with its frontal appendage blades to capture and feed on small invertebrates. Megarachne also possessed a large and circular second opisthosomal tergite (the second dorsal segment of the abdomen), the function of which remains unknown.[3]

Megarachne was very similar to other mycteroptid eurypterids in appearance, a group distinguished from other mycteropoids by the parabolic shape of their prosoma (the head plate), hastate telsons (the hindmost part of the body being shaped like a gladius, a Roman sword) with paired keel-shaped projections on the underside,[4] and heads with small compound eyes that were roughly trapezoidal in shape.[5]

History of research

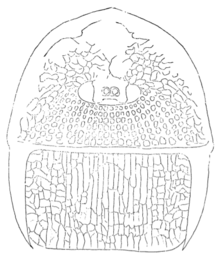

Megarachne servinei was originally described in 1980 by the Argentinean paleontologist Mario Hünicken. The generic name, composed of the Ancient Greek μέγας (megas) meaning "great" and Latin arachne meaning "spider", translates to "great spider". The holotype (now stored at the Museum of Paleontology at the National University of Córdoba) was recovered from the Pallero Member of the Bajo de Véliz Formation of Argentina, which has been dated to the Gzhelian age, 303.7 to 298.9 million years ago.[6][7] The specimen preserves the carapace, the first two tergites, three partial appendages and what is possibly a coxa (the proximalmost limb segment).[1][6]

Hünicken wrongly identified the specimen as a mygalomorph spider (the group that includes tarantulae) based on the shape of the carapace, the 15-millimetre (0.59 in) wide circular eye tubercle (round outgrowth) located in the center of the head between the two eyes and a circular structure behind the first body segment which he identified as the "moderately hairy" abdomen. Hünicken's identification relied heavily on X-ray microtomography of the holotype. Additional hidden structures – such as a sternum and labium, coxae and cheliceral fangs – were also extrapolated from the X-radiographs.[6]

With an estimated length of 33.9 cm (13.3 in) based on the assumption that the fossil was of a spider, and a legspan estimated to be 50 centimetres (20 in), Megarachne servinei would have been the largest spider to have ever existed, exceeding the goliath birdeater (Theraphosa blondi) which has a maximum legspan of around 30 cm (12 in). Because of its status as the "largest spider to have ever lived", Megarachne quickly became popular. Based on Hünicken's detailed description of the fossil specimen and various other illustrations and reconstructions made by him, reconstructions of Megarachne as a giant spider were set up in museums around the world.[8][7]

The identification of the specimen as a spider was doubted by some arachnologists, such as Shear and colleagues (1989), who stated that whilst Megarachne had been assigned to the Araneae, it "may represent an unnamed order or a ricinuleid".[9] Even Hünicken himself acknowledged discrepancies in the morphology of the fossil that could not be accommodated with an arachnid identity. These discrepancies included an unusual cuticular ornamentation, the carapace being divided into frontal and rear parts by a suture and spatulate (having a broad, rounded end) chelicerae (already noted by Hünicken as a strange feature as no known spider possesses spatulate chelicerae), all features unknown in other spiders. However, the holotype was by then deposited in a bank vault so other paleontologists only had access to plaster casts.[8]

In 2005, a second, more complete specimen consisting of a part and counterpart (the matching halves of a compression fossil) was recovered, preserving parts of the front section of the body, as well as coxae possibly from the fourth pair of appendages, was recovered from the same locality and horizon.[6] A research team led by the British paleontologist and arachnologist Paul A. Selden and also consisting of Hünicken and Argentinean arachnologist José A. Corronca reexamined the holotype in light of the new discovery. They concluded that Megarachne servinei was a large eurypterid (a group also known as "sea scorpions"), not a spider.[3][7] Although Hünicken had misidentified Megarachne, his identification as an arachnid was not entirely absurd as the two groups are closely related.[10] A morphological comparison with other eurypterids indicated that Megarachne most closely resembled another large Permo-Carboniferous eurypterid, the mycteroptid Woodwardopterus scabrosus which is known only from a single specimen.[3] Selden and colleagues (2005) concluded that despite only being represented by two known specimens, Megarachne is the most complete eurypterid discovered in Carboniferous deposits in South America so far.[1]

Classification

Megarachne was part of the stylonurine suborder, a relatively rare clade of eurypterids. Within the stylonurines, Megarachne is a member of the superfamily Mycteropoidea and its constituent family Mycteropidae, which includes the close relatives Woodwardopterus and Mycterops.[4]

Fossilized remains of the second tergite of the mycteroptid Woodwardopterus were compared to the fossil remains of Megarachne by Selden and colleagues (2005), which revealed that they were virtually identical, including features previously not noted in Woodwardopterus, such as radiating lines covering the tergite. It was concluded that Megarachne and Woodwardopterus were part of the same family by Selden and colleagues (2005), with two primary differences; the tergites and the mucrones on the carapace are more sparsely packed in Megarachne and the protrusion of the anteroedian (i.e. before the middle) carapace, seen prominently in Megarachne, does not occur in Woodwardopterus.[3]

It has been suggested that three of the four genera that constitute the Mycteroptidae, Mycterops, Woodwardopterus and Megarachne, might represent different ontogenetic stages (different developmental stages of the animal during its life) of each other based on their morphology and the size of the specimens.[4] Should this interpretation be correct, the sparse mucrones of Megarachne might be because of its age, as Megarachne is significantly larger than Woodwardopterus. The smallest genus, Mycterops, has even more densely packed ornaments on its carapace and tergite and might thus be the youngest ontogenetic stage of the animal.[3] Should Mycterops, Megarachne and Woodwardopterus represent the same animal, the name taking priority would be Mycterops as it was named first, in 1886.[11]

The cladogram below is adapted from Lamsdell and colleagues (2010)[4] and shows the relationship of Megarachne within the suborder Stylonurina.

| Stylonurina |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

Both known specimens of Megarachne have been recovered from the Bajo de Véliz Formation of Argentina, dated to the Gzhelian stage of the Late Carboniferous.[6][7] The environment of the Bajo de Véliz formation was, unlike the typical living environments of eurypterids (especially the swimming eurypterids of the suborder Eurypterina), a freshwater environment[6] in a floodplain.[12] Similar Late Carboniferous floodplains with fossilized remnants discovered in modern-day Australia suggest a flora dominated by different types of pteridosperms with pockets of isoetoid lycopsids.[13]

During Megarachne's time, Argentina and the rest of South America was part of the ancient supercontinent Gondwana which was beginning to fuse with the northern continents of Euramerica, North China, Siberia and Kazakhstania to form Pangaea.[13] In addition to Megarachne, the Bajo de Véliz Formation preserves a wide array of fossilized flying insects, such as Rigattoptera (classified in the order Protorthoptera),[14] but as a freshwater predator, Megarachne would probably not have fed on them. Instead, the blades on the frontal appendages of Megarachne would have allowed it to sweep-feed, raking through the soft sediment of the rivers it inhabited in order to capture and feed on small invertebrates.[3] This feeding strategy was common to other mycteropoids.[4]

In comparison to the comparatively warm climate of the earlier parts of the Carboniferous, the Late Carboniferous was relatively cold globally. This climate change likely occurred during the Middle Carboniferous due to falling CO

2 levels in the atmosphere and high oxygen levels. The Southern Hemisphere, where Argentina was and still is located, may even have experienced glaciation with large continental ice sheets similar to the modern glacial ice sheets of the Arctic and Antarctica, or smaller glaciers in dispersed centers. The spread of the ice sheets also affected sea levels, which would rise and fall throughout the period. Late Carboniferous flora was low in diversity but also developed uniformly throughout Gondwana. The plant life consisted of pteridosperm trees such as Nothorhacopteris, Triphyllopteris and Botrychiopsis, and lycopsid trees Malanzania, Lepidodendropsis and Bumbudendron. The plant fossils present also suggest that it was subject to monsoons during certain time intervals.[13]

In popular culture

During the production of the 2005 British documentary Walking with Monsters, Megarachne was slated to appear as a giant tarantula-like spider hunting the cat-sized reptile Petrolacosaurus in the segment detailing the Carboniferous, with the reconstruction closely following what was thought to be known of the genus at the time the series began production. The actual identity of the genus, as a eurypterid, was only discovered well into production and by then it was far too late to update the reconstructions. The scenes were left in, but the giant spider was renamed as an unspecified species belonging to the primitive spider suborder Mesothelae, a suborder that actually exists but with genera much smaller than, and looking considerably different from, the spider featured in the program.[7]

References

- Selden, Paul A; Corronca, José A; Hünicken, Mario A (22 March 2005). "The true identity of the supposed giant fossil spider Megarachne – Abstract". Biology Letters. ScienceBlogs. 1 (1): 44–48. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0272. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 1629066. PMID 17148124.

- Lamsdell, James C.; Braddy, Simon J. (2010-04-23). "Cope's Rule and Romer's theory: patterns of diversity and gigantism in eurypterids and Palaeozoic vertebrates". Biology Letters. ScienceBlogs. 6 (2): 265–69. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0700. PMC 2865068. PMID 19828493.

- Selden, Paul A; Corronca, José A; Hünicken, Mario A (22 March 2005). "The true identity of the supposed giant fossil spider Megarachne – 4. Discussion". Biology Letters. ScienceBlogs. 1 (1). doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0272. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 1629066. PMID 17148124.

- Lamsdell, James C.; Braddy, Simon J.; Tetlie, O. Erik (2010). "The systematics and phylogeny of the Stylonurina (Arthropoda: Chelicerata: Eurypterida)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1080/14772011003603564.

- Størmer, Leif (1955). "Merostomata". Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part P Arthropoda 2, Chelicerata. p. 39.

- Selden, Paul A; Corronca, José A; Hünicken, Mario A (22 March 2005). "The true identity of the supposed giant fossil spider Megarachne – 3. Results". Biology Letters. ScienceBlogs. 1 (1). doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0272. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 1629066. PMID 17148124.

- Switek, Brian (2010). "Megarachne, the Giant Spider That Wasn't". Biology Letters. ScienceBlogs. 1 (1): 44–48. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0272. PMC 1629066. PMID 17148124. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- Selden, Paul A; Corronca, José A; Hünicken, Mario A (22 March 2005). "The true identity of the supposed giant fossil spider Megarachne – 1. Introduction". Biology Letters. ScienceBlogs. 1 (1). doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0272. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 1629066. PMID 17148124.

- Shear, W. A.; Palmer, J. M.; Coddington, J. A.; Bonamo, P. M. (1989). "A Devonian spinneret: early evidence of spiders and silk use". Science. 246 (4929): 479–81. Bibcode:1989Sci...246..479S. doi:10.1126/science.246.4929.479. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17788699.

- Lamsdell, James C. (2013-01-01). "Revised systematics of Palaeozoic 'horseshoe crabs' and the myth of monophyletic Xiphosura". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 167 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00874.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2018. A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives. In World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern, p. 19

- "Bajo de Veliz (CORD collection), Carboniferous of Argentina". Fossilworks. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- DiMichele, W. A.; Pfefferkorn, H. W.; Gastaldo, R. A. (2001). "Response of Late Carboniferous And Early Permian Plant Communities To Climate Change". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 29: 461–69. Bibcode:2001AREPS..29..461D. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.29.1.461.

- Pinto, I.D. (1996). "'Rigattoptera ornellasae' n. g. n. sp., a new fossil insect from the Carboniferous of Argentina". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Monatshefte. 1: 43–47. doi:10.1127/njgpm/1996/1996/43.

External links