Canterbury

Canterbury (/ˈkæntəbri/ (![]()

| Canterbury | |

|---|---|

Canterbury lies on the River Great Stour | |

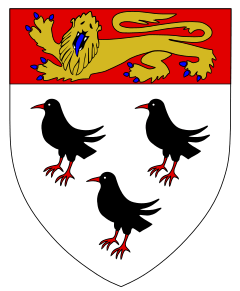

Arms of Canterbury | |

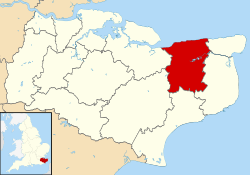

Canterbury Location within Kent | |

| Population | 55,240 (2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TR145575 |

| • London | 54 miles (87 km)[2] |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CANTERBURY |

| Postcode district | CT1–CT4 |

| Dialling code | 01227 |

| Police | Kent |

| Fire | Kent |

| Ambulance | South East Coast |

| UK Parliament | |

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of the Church of England and the worldwide Anglican Communion owing to the importance of St Augustine, who served as the apostle to the pagan Kingdom of Kent around the turn of the 7th century. The city's cathedral became a major focus of pilgrimage following the 1170 martyrdom of Thomas Becket, although it had already been a well-trodden pilgrim destination since the murder of St Alphege by the men of King Canute in 1012. A journey of pilgrims to Becket's shrine served as the frame for Geoffrey Chaucer's 14th century classic The Canterbury Tales.

Canterbury is a popular tourist destination: consistently one of the most-visited cities in the United Kingdom,[4] the city's economy is heavily reliant upon tourism. The city has been occupied since Paleolithic times and served as the capital of the Celtic Cantiaci and Jute Kingdom of Kent. Many historical structures fill the area, including a city wall founded in Roman times and rebuilt in the 14th century, the ruins of St Augustine's Abbey and a Norman castle, and the oldest extant school in the world, the King's School. Modern additions include the Marlowe Theatre and the St Lawrence Ground, home of the Kent County Cricket Club. There is also a substantial student population, brought about by the presence of the University of Kent, Canterbury Christ Church University, the University for the Creative Arts, and the Girne American University Canterbury campus.[5] Canterbury remains, however, a small city in terms of geographical size and population, when compared with other British cities.

Name

The Roman settlement of Durovernum Cantiacorum ("Kentish Durovernum") occupied the location of an earlier British town whose ancient British name has been reconstructed as *Durou̯ernon ("stronghold by the alder grove"),[6] although the name is sometimes supposed to have derived from various British names for the Stour.[7] (Medieval variants of the Roman name include Dorobernia and Dorovernia.)[7] In Sub-Roman Britain, it was known in Old Welsh as Cair Ceint ("stronghold of Kent").[8][9] Occupied by the Jutes, it became known in Old English as Cantwareburh ("stronghold of the Kentish men"),[10] which developed into the present name.

History

Early history

The Canterbury area has been inhabited since prehistoric times. Lower Paleolithic axes, and Neolithic and Bronze Age pots have been found in the area.[11] Canterbury was first recorded as the main settlement of the Celtic tribe of the Cantiaci, which inhabited most of modern-day Kent. In the 1st century AD, the Romans captured the settlement and named it Durovernum Cantiacorum.[6] The Romans rebuilt the city, with new streets in a grid pattern, a theatre, a temple, a forum, and public baths.[12] Although they did not maintain a major military garrison, its position on Watling Street relative to the major Kentish ports of Rutupiae (Richborough), Dubrae (Dover), and Lemanae (Lymne) gave it considerable strategic importance.[13] In the late 3rd century, to defend against attack from barbarians, the Romans built an earth bank around the city and a wall with seven gates, which enclosed an area of 130 acres (53 ha).[12]

Despite being counted as one of the 28 cities of Sub-Roman Britain,[8][9] it seems that after the Romans left Britain in 410 Durovernum Cantiacorum was abandoned for around 100 years, except by a few farmers and gradually decayed.[14] Over the next 100 years, an Anglo-Saxon community formed within the city walls, as Jutish refugees arrived, possibly intermarrying with the locals.[15] In 597, Pope Gregory the Great sent Augustine to convert its King Æthelberht to Christianity. After the conversion, Canterbury, being a Roman town, was chosen by Augustine as the centre for his episcopal see in Kent, and an abbey and cathedral were built. Augustine thus became the first Archbishop of Canterbury.[16] The town's new importance led to its revival, and trades developed in pottery, textiles, and leather. By 630, gold coins were being struck at the Canterbury mint.[17] In 672, the Synod of Hertford gave the see of Canterbury authority over the entire English Church.[10]

In 842 and 851, Canterbury suffered great loss of life during Danish raids. In 978, Archbishop Dunstan refounded the abbey built by Augustine, and named it St Augustine's Abbey.[18] The Siege of Canterbury saw a large Viking army besiege Canterbury in 1011, culminating in the city being pillaged and the eventual murder of Archbishop Alphege in 19 April 1012.[19] Remembering the destruction caused by the Danes, the inhabitants of Canterbury did not resist William the Conqueror's invasion in 1066.[10] William immediately ordered a wooden motte-and-bailey castle to be built by the Roman city wall. In the early 12th century, the castle was rebuilt with stone.[20]

After the murder of the Archbishop Thomas Becket at the cathedral in 1170, Canterbury became one of the most notable towns in Europe, as pilgrims from all parts of Christendom came to visit his shrine.[21] This pilgrimage provided the framework for Geoffrey Chaucer's 14th-century collection of stories, The Canterbury Tales.[22] Canterbury Castle was captured by the French Prince Louis during his 1215 invasion of England, before the death of John caused his English supporters to desert his cause and support the young Henry III.[13]

Canterbury is associated with several saints from this period who lived in Canterbury:

- Saint Augustine of Canterbury

- Saint Anselm of Canterbury

- Saint Thomas Becket

- Saint Mellitus

- Saint Theodore of Tarsus

- Saint Dunstan

- Saint Adrian of Canterbury

- Saint Alphege

- Saint Æthelberht of Kent

14th–17th centuries

The Black Death hit Canterbury in 1348. At 10,000, Canterbury had the 10th largest population in England; by the early 16th century, the population had fallen to 3,000. In 1363, during the Hundred Years' War, a Commission of Inquiry found that disrepair, stone-robbing and ditch-filling had led to the Roman wall becoming eroded. Between 1378 and 1402, the wall was virtually rebuilt, and new wall towers were added.[23] In 1381, during Wat Tyler's Peasants' Revolt, the castle and Archbishop's Palace were sacked, and Archbishop Sudbury was beheaded in London. Sudbury is still remembered annually by the Christmas mayoral procession to his tomb at Canterbury Cathedral. In 1413 Henry IV became the only sovereign to be buried at the cathedral. In 1448 Canterbury was granted a City Charter, which gave it a mayor and a high sheriff; the city still has a Lord Mayor and Sheriff.[24] In 1504 the cathedral's main tower, the Bell Harry Tower, was completed, ending 400 years of building.

During the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the city's priory, nunnery and three friaries were closed. St Augustine's Abbey, the 14th richest in England at the time, was surrendered to the Crown, and its church and cloister were levelled. The rest of the abbey was dismantled over the next 15 years, although part of the site was converted to a palace.[25] Thomas Becket's shrine in the cathedral was demolished and all the gold, silver and jewels were removed to the Tower of London, and Becket's images, name and feasts were obliterated throughout the kingdom, ending the pilgrimages.

By the 17th century, Canterbury's population was 5,000; of whom 2,000 were French-speaking Protestant Huguenots, who had begun fleeing persecution and war in the Spanish Netherlands in the mid-16th century. The Huguenots introduced silk weaving into the city, which by 1676 had outstripped wool weaving.[26]

In 1620 Robert Cushman negotiated the lease of the Mayflower at 59 Palace Street for the purpose of transporting the Pilgrims to America.

In 1647, during the English Civil War, riots broke out when Canterbury's puritan mayor banned church services on Christmas Day. The rioters' trial the following year led to a Kent revolt against the Parliamentarian forces, contributing to the start of the second phase of the war. However, Canterbury surrendered peacefully to the Parliamentarians after their victory at the Battle of Maidstone.[27]

18th century–present

The city's first newspaper, the Kentish Post, was founded in 1717.[28] It merged with the newly founded Kentish Gazette in 1768.[29]

By 1770, the castle had fallen into disrepair, and many parts of it were demolished during the late 18th century and early 19th century.[30] In 1787 all the gates in the city wall, except for Westgate—the city jail—were demolished as a result of a commission that found them impeding to new coach travel.[31] Canterbury Prison was opened in 1808 just outside the city boundary.[32] By 1820 the city's silk industry had been killed by imported Indian muslins;[26] its trade was thereafter mostly limited to hops and wheat.[13] The Canterbury & Whitstable Railway, the world's first passenger railway,[33] was opened in 1830;[34] bankrupt by 1844, it was purchased by the South Eastern Railway, which connected the town to its larger network in 1846.[35] The London, Chatham, and Dover arrived in 1860;[36] the competition and cost-cutting between the lines was resolved by merging them as the South Eastern and Chatham in 1899.[37] In 1848, St Augustine's Abbey was refurbished for use as a missionary college for the Church of England's representatives in the British colonies.[13] Between 1830 and 1900, the city's population grew from 15,000 to 24,000.[33]

During the First World War, a number of barracks and voluntary hospitals were set up around the city, and in 1917 a German bomber crash-landed near Broad Oak Road.[38]

During the Second World War, 10,445 bombs dropped during 135 separate raids destroyed 731 homes and 296 other buildings in the city, including the missionary college and Simon Langton Girls' Grammar Schools.[39] 119 civilian lives were lost through enemy action in the borough.[40] The most devastating raid was on 1 June 1942 during the Baedeker Blitz.[38] On that day alone, 43 people were killed and nearly 100 sustained wounds. Some 800 buildings were destroyed with 1,000 seriously damaged. Although its library was destroyed,[41] the cathedral did not sustain extensive bomb damage and the local Fire Wardens doused any flames on the wooden roof.[42] On 31 October 1942, the Luftwaffe made a further raid on Canterbury when thirty Focke-Wulf fighter-bombers, supported by sixty fighter escorts, launched a low-level raid on Canterbury. Civilians were strafed and bombed throughout the city resulting in twenty-eight bombs dropped and 30 people killed. Three German planes were shot down by the RAF.

Before the end of the war, architect Charles Holden drew up plans to redevelop the city centre, but locals were so opposed that the Citizens' Defence Association was formed and swept to power in the 1945 municipal elections. Rebuilding of the city centre eventually began 10 years after the war.[43] A ring road was constructed in stages outside the city walls some time afterwards to alleviate growing traffic problems in the city centre, which was later pedestrianised. The biggest expansion of the city occurred in the 1960s, with the arrival of the University of Kent at Canterbury and Christ Church College.[43]

The 1980s saw visits from Pope John Paul II and Queen Elizabeth II, and the beginning of the annual Canterbury Festival.[44] Canterbury received its own radio station in CTFM, now KMFM Canterbury, in 1997. Between 1999 and 2005, the Whitefriars Shopping Centre underwent major redevelopment. In 2000, during the redevelopment, a major archaeological project was undertaken by the Canterbury Archaeological Trust, known as the Big Dig,[45] which was supported by Channel Four's Time Team.[46]

Another famous visitor was Mahatma Gandhi, who came to the city[47] in October 1931; he met[48] Hewlett Johnson, the pro-communist then Dean of Canterbury.

The extensive restoration of the cathedral that was underway in mid 2018 was part of a 2016-2021 schedule that includes replacement of the nave roof, improved landscaping and accessibility, new visitor facilities and a general external restoration.[49] The so-called Canterbury Journey project was expected to cost nearly £25 million.[50]

Governance

The Member of Parliament for the Canterbury constituency, which includes Whitstable, is Rosie Duffield of the Labour Party.

Canterbury, along with Whitstable and Herne Bay, is in the City of Canterbury local government district. The city's urban area consists of the six electoral wards of Barton, Blean Forest, Northgate, St Stephens, Westgate, and Wincheap. These wards have eleven of the fifty seats on the Canterbury City Council. Six of these seats are held by the Liberal Democrats, four by the Conservatives and one by Labour.

The city became a county corporate in 1461, and later a county borough under the Local Government Act 1888. In 1974 it lost its status as the smallest county borough in England, after the Local Government Act 1972, and came under the control of Kent County Council.

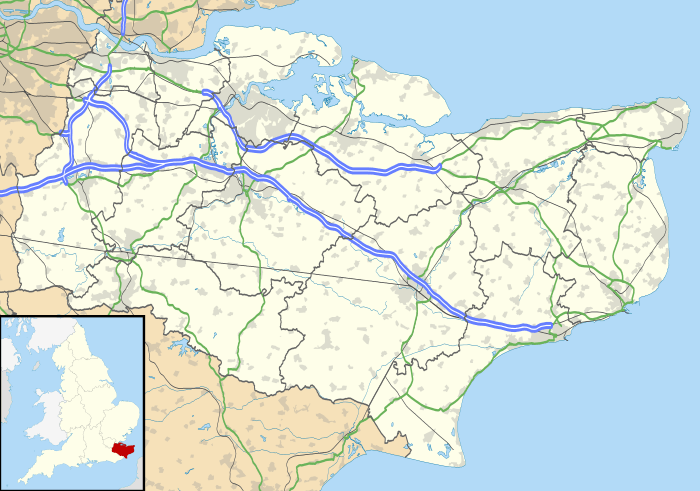

Geography

Canterbury is in east Kent, about 55 miles (89 km) east-southeast of London. The coastal towns of Herne Bay and Whitstable are 6 miles (10 km) to the north, and Faversham is 8 miles (13 km) to the northwest. Nearby villages include Chartham, Rough Common, Sturry and Tyler Hill. The civil parish of Thanington Without is to the southwest; the rest of the city is unparished. Harbledown, Wincheap and Hales Place are suburbs of the city.

The city is on the River Stour or Great Stour, flowing from its source at Lenham north-east through Ashford to the English Channel at Sandwich. As it flows north-east, the river divides west of the city, one branch flowing through the city centre, and the other around the position of the former walls. The two branches create several river islands before finally recombining around the town of Fordwich on the edge of the marshland north east of the city.[51] The Stour is navigable on the tidal section to Fordwich, although above this point canoes and other small craft can be used. Punts and rowed river boats are available for hire in Canterbury.[52] The geology of the area consists mainly of brickearth overlying chalk. Tertiary sands overlain by London clay form St. Thomas's Hill and St. Stephen's Hill about a mile northwest of the city centre.[53]

Climate

Canterbury experiences an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb), similar to almost all of the United Kingdom. Canterbury enjoys mild temperatures all year round, being between 1.8 °C (35.2 °F) and 22.8 °C (73 °F). There is relatively little rainfall throughout the year.

| Climate data for Canterbury | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

10.7 (51.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.8 (62.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

15.3 (59.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.3 (39.7) |

4.3 (39.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.8 (62.2) |

16.9 (62.4) |

14.3 (57.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.1 (44.8) |

5.3 (41.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

1.8 (35.2) |

3.5 (38.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

7.7 (45.9) |

10.5 (50.9) |

12.9 (55.2) |

12.8 (55.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

4.8 (40.6) |

2.5 (36.5) |

6.9 (44.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 62.2 (2.45) |

42.2 (1.66) |

41.3 (1.63) |

42.9 (1.69) |

50.0 (1.97) |

39.0 (1.54) |

40.0 (1.57) |

51.2 (2.02) |

61.6 (2.43) |

83.2 (3.28) |

68.8 (2.71) |

63.4 (2.50) |

645.8 (25.43) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 60.9 | 80.7 | 116.5 | 174.2 | 206.0 | 206.4 | 221.8 | 214.9 | 155.2 | 125.0 | 73.3 | 48.6 | 1,683.3 |

| Source 1: [54] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: [55] | |||||||||||||

Demography

| 2001 UK Census | Canterbury city | Canterbury district | England |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 43,432 | 135,278 | 49,138,831 |

| Foreign born | 11.6% | 5.1% | 9.2% |

| White | 95% | 97% | 91% |

| Asian | 1.8% | 1.6% | 4.6% |

| Black | 0.7% | 0.5% | 2.3% |

| Christian | 68% | 73% | 72% |

| Muslim | 1.1% | 0.6% | 3.1% |

| Hindu | 0.8% | 0.4% | 1.1% |

| No religion | 20% | 17% | 15% |

| Unemployed | 3.0% | 2.7% | 3.3% |

At the 2001 UK census,[56][57][58][59][60][61] C the total population of the city's urban area wards was 43,432, with 135,278 within the Canterbury district. In 2011, the total district population was counted as 151,200, with an 11.7% increase from 2001.[62]

By 2011, the population of the city had grown to over 55,000.[63]

For 2001, residents of the city had an average age of 37.1 years, younger than the 40.2 average of the district and the 38.6 average for England. Of the 17,536 households, 35% were one-person households, 39% were couples, 10% were lone parents, and 15% other. Of those aged 16–74 in the city, 27% had a higher education qualification, higher than the 20% national average.

Compared with the rest of England, the city had an above-average proportion of foreign-born residents, at around 12%. Ninety-five percent of residents were recorded as white; the largest minority group was recorded as Asian, at 1.8% of the population. Religion was recorded as 68.2% Christian, 1.1% Muslim, 0.5% Buddhist, 0.8% Hindu, 0.2% Jewish, and 0.1% Sikh. The rest either had no religion, an alternative religion, or did not state their religion.

| Population growth in Canterbury since 1901 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 2001 | |||||||||

| Population | 24,899 | 24,626 | 23,737 | 24,446 | 26,999 | 27,795 | 30,415 | 33,155 | 43,432 | |||||||||

| Source: A Vision of Britain through Time | ||||||||||||||||||

Economy

Canterbury district retained approximately 4,761 businesses, up to 60,000 full and part-time employees and was worth £1.3 billion in 2001.[64] This made the district the second largest economy in Kent.[64] Today, the three primary sectors are tourism, higher education and retail.[65]

In 2015, the value of tourism to the city of Canterbury was over £450 million; 7.2 million people visited that year. A full 9,378 jobs were supported by tourism, an increase of 6% over the previous year.[66] The two universities provided an even greater benefit. In 2014/2015, the University of Kent and Canterbury Christ Church University were worth £909m to city's economy and accounted for 16% of all jobs.[67]

Unemployment in the city has dropped significantly since 2001 owing to the opening of the Whitefriars shopping complex which introduced thousands of job opportunities.[68] The city's economy benefits mainly from significant economic projects such as the Canterbury Enterprise Hub, Lakesview International Business Park and the Whitefriars retail development.[64]

The registered unemployment rate as of September 2011 stood at 5.7%. By May 2018, the rate had dropped to 1.8%; in fact, Kent in general had a moderate unemployment rate of 2%. This data considers only people claiming either Jobseekers Allowance or Universal Credit principally for the reason of being unemployed. It does not include those without access to such benefits.[69] At the time, the national rate was 4.2%.[70]

In July 2020, a study ranked Canterbury as the best UK location to start a business.[71]

Culture

Landmarks

Canterbury Cathedral is the Mother Church of the Anglican Communion and seat of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Founded in 597 AD by Augustine, it forms a World Heritage Site, along with the Saxon St. Martin's Church and the ruins of St Augustine's Abbey. With one million visitors per year, it is one of the most visited places in the country. Services are held at the cathedral three or more times a day.[72][73]

The Roman Museum houses an in situ mosaic pavement dating from around 300 AD.[74] Surviving structures from the Roman times include Queningate, a blocked gate in the city wall, and the Dane John Mound, once part of a Roman cemetery.[75] The Dane John Gardens were built beside the mound in the 18th century, and a memorial was placed on the mound's summit.[76] A windmill was on the mound between 1731 and 1839.

The ruins of the Norman Canterbury Castle and St Augustine's Abbey are both open to the public. The medieval St Margaret's Church now houses "The Canterbury Tales", in which life-sized character models reconstruct Geoffrey Chaucer's stories. The Westgate is now a museum relating to its history as a jail. The medieval church of St Alphege became redundant in 1982 but had a new lease of life as the Canterbury Urban Studies Centre, later renamed the Canterbury Environment Centre; the building is used by the King's School. The Old Synagogue, now the King's School Music Room, is one of only two Egyptian Revival synagogues still standing. The city centre contains many timber-framed 16th and 17th century houses, however there are far fewer than there were before the Second World War, as many were damaged during the Baedeker Blitz. Many are still standing, including the "Old Weaver's House" used by the Huguenots.[77] St Martin's Mill is the only surviving mill out of the six known to have stood in Canterbury. It was built in 1817 and worked until 1890; it is now a house conversion.[78] St Thomas of Canterbury Church is the only Roman Catholic church in the city and contains relics of Thomas Becket.[79]

Canterbury Heritage Museum housed many exhibits - including the Rupert Bear Museum. The museum has now closed despite campaigning to keep the museum open.[80] Herne Bay Times has reported that the Heritage at Risk Register includes 19 listed buildings in Canterbury which need urgent repair but for which the council has insufficient funds.[81]

Theatres

The city's theatre and concert hall is the Marlowe Theatre named after Christopher Marlowe, who was born in the city in Elizabethan times. He was baptised in the city's St George's Church, which was destroyed during the Second World War.[82] The old Marlowe Theatre was located in St Margaret's Street and housed a repertory theatre. The Gulbenkian Theatre, at the University of Kent, also serves the city, housing also a cinema and café.[83] The Marlowe Theatre was completely rebuilt and reopened in October 2011.

Besides the two theatres, theatrical performances take place at several areas of the city, for instance the cathedral and St Augustine's Abbey. The premiere of Murder in the Cathedral by T. S. Eliot took place at Canterbury Cathedral.[84]

The oldest surviving Tudor theatre in Canterbury is now the Shakespeare,[85] formerly known as Casey's. There are several theatre groups based in Canterbury, including the University of Kent Students' Union's T24 Drama Society, The Canterbury Players[86] and Kent Youth Theatre.

Marlowe Theatre

The redeveloped Marlowe Theatre is (at the time of writing) the largest theatre in the region, offering touring productions and concerts. The programme includes musicals, drama, ballet, contemporary dance, classical orchestras, opera, children's shows, pantomime, stand-up comedy and concerts. There is also a second performance space called the Marlowe Studio, dedicated to creative activity and the programming of new work. The Marlowe Theatre can be seen from many points throughout the city centre, considering it is the only modern and tall structure.

Music

The cathedral

Medieval

Polyphonic music written for the monks of Christ Church Priory (the cathedral) survives from the 13th century. The cathedral may have had an organ as early as the 12th century,[87] though the names of organists are only recorded from the early 15th century.[88] One of the earliest named composers associated with Canterbury Cathedral was Leonel Power, who was appointed master of the new Lady Chapel choir formed in 1438.

Post-Reformation

The Reformation brought a period of decline in the cathedral's music which was revived under Dean Thomas Neville in the early 17th century. Neville introduced instrumentalists into the cathedral's music who played cornett and sackbut, probably members of the city's band of waits. The cathedral acquired sets of recorders, lutes and viols for the use of the choir boys and lay-clerks.[87]

The city

Early modern

As was common in English cities in the Middle Ages, Canterbury employed a town band known as the Waits. There are records of payments to the Waits starting from 1402, though they probably existed earlier than this. The Waits were disbanded by the city authorities in 1641 for 'misdemeanors' but were reinstated in 1660 when they played for the visit of King Charles II on his return from exile.[89] Waits were eventually abolished nationally by the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835. A modern early music group called The Canterbury Waits has revived the name.[90]

The Canterbury Catch Club was a musical and social club which met in the city between 1779 and 1865. The club (male only) met weekly in the winter. It employed an orchestra to assist in performances in the first half of the evening. After the interval, the members sang catches and glees from the club's extensive music library (now deposited at the Cathedral Archives in Canterbury).[91]

Contemporary

The city gave its name to a musical genre known as the Canterbury Sound or Canterbury Scene, a group of progressive rock, avant-garde and jazz musicians established within the city during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Some very notable Canterbury bands were Soft Machine, Caravan, Matching Mole, Egg, Hatfield and the North, National Health, Gilgamesh, Soft Heap, Khan, Camel and In Cahoots. Over the years, with band membership changes and new bands evolving, the term has been used to describe a musical style or subgenre, rather than a regional group of musicians.[92] During the 1970-80's the Canterbury 'Odeon' now the site of the 'New Marlow' played host to many of the Punk and new wave bands of the era including, The Clash, The Ramones, Blondie, Sham69, Magazine, XTC, Dr Feelgood, Elvis Costello and The Attractions, and The Stranglers.

The University of Kent has hosted concerts by bands including Led Zeppelin[93] and The Who.[94] Ian Dury, front man of the 70's rock band Ian Dury and the Blockheads, taught Fine Art at UCA Canterbury[95] and also performed in the city in the early incarnation of his band Kilburn and the High Roads. During the late seventies and early eighties the Canterbury Odeon hosted a number of major acts, including The Cure[96] and Joy Division.[97] The Marlowe Theatre is also used for many musical performances, such as Don McLean in 2007,[98] and Fairport Convention in 2008.[99] A regular music and dance venue is the Westgate Hall.

The Canterbury Choral Society gives regular concerts in Canterbury Cathedral, specialising in the large-scale choral works of the classical repertory.[100] The Canterbury Orchestra, founded in 1953, is a thriving group of enthusiastic players who regularly tackle major works from the symphonic repertoire.[101] Other musical groups include the Canterbury Singers (also founded in 1953), Cantemus, and the City of Canterbury Chamber Choir.[102] The University of Kent has a Symphony Orchestra, a University Choir, a Chamber Choir, and a University Concert Band and Big Band.[103]

The Canterbury Festival takes place over two weeks in October each year in Canterbury and the surrounding towns. It includes a wide range of musical events ranging from opera and symphony concerts to world music, jazz, folk, etc., with a Festival Club, a Fringe and Umbrella events.[104] Canterbury also hosts the annual Lounge On The Farm festival in July, which mainly sees performances from rock, indie and dance artists.

The reggae/ska musician Judge Dread played his last gig at the Penny Theatre. His final words were "Let's hear it for the band." He then went offstage, suffered a major heart attack and died, despite help from both ambulance crews and the audience.

Composers

Composers with an association with Canterbury include

- Thomas Tallis (c. 1505–1585), became a lay clerk (singing man) at Canterbury Cathedral c. 1540 and was subsequently appointed a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal in 1543.[87]

- John Ward (1571–1638), born in Canterbury, a chorister at Canterbury Cathedral, composed madrigals, works for viol consort, services, and anthems.

- Orlando Gibbons (1583–1625), organist, composer and Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, who died in Canterbury and was buried in the cathedral.

- William Flackton (1709–1798), born in Canterbury, a chorister at Canterbury Cathedral, was an organist, viola player and composer.

- John Marsh (1752–1828), lawyer, amateur composer and concert organiser, wrote two symphonies for the Canterbury Orchestra before moving to Chichester in 1784.

- Thomas Clark (1775–1859), shoemaker and organist at the Methodist church in Canterbury, composer of 'West Gallery' hymns and psalm tunes.[105]

- Sir George Job Elvey (1816–1893), organist and composer, was born in Canterbury and trained as a chorister at the cathedral.

- Alan Ridout (1934–1996) educator and broadcaster, composer of church, orchestral and chamber music.

- Sir Peter Maxwell Davies was appointed an Honorary Fellow of Canterbury Christ Church University at a ceremony in Canterbury Cathedral.

- Many Canterbury Cathedral organists composed services, anthems, hymns, etc.

Sport

St Lawrence Ground is notable as one of the two grounds used regularly for first-class cricket that have a tree within the boundary (the other is the City Oval in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa). It is the home ground of Kent County Cricket Club and has hosted several One Day Internationals, including one England match during the 1999 Cricket World Cup.[106]

Canterbury City F.C. reformed in 2007 as a community interest company and currently compete in the Southern Counties East Football League. The previous incarnation of the club folded in 2001.[107] Canterbury RFC were founded in 1926 and became the first East Kent club to achieve National League status and currently play in the fourth tier, National League 2 South.[108]

The Tour de France has visited the city twice. In 1994 the tour passed through, and in 2007 it held the finish for Stage 1.[109]

Canterbury Hockey Club is one of the largest clubs in the country and enter teams in both the Men's and Women's England Hockey Leagues.[110] Former Olympic gold medal winner Sean Kerly also a member of the club.[111]

Sporting activities for the public are provided at the Kingsmead Leisure Centre, which has a 33-metre (108 ft) swimming pool and a sports hall for football, basketball, and badminton.[112]

Public transport

Railway

Canterbury was the terminus of the Canterbury & Whitstable Railway (known locally as the Crab and Winkle line) which was a pioneer line, opened on 3 May 1830, and closed in 1953. The Canterbury & Whitstable was the first regular passenger steam railway in the world.[113] The first station in Canterbury was at North Lane.

Canterbury has two railway stations, called Canterbury West and Canterbury East (despite both stations being west of the city centre: Canterbury West is to the northwest and Canterbury East is to the southwest). Both stations are operated by Southeastern. Canterbury West station, on the South Eastern Railway from Ashford, was opened on 6 February 1846, and on 13 April the line to Ramsgate was completed. Canterbury West is served by High Speed 1 trains to London St Pancras, slower stopping services to London Charing Cross and London Victoria as well as by trains to Ramsgate and Margate. Canterbury East, the more central of the two stations, was opened by the London, Chatham & Dover Railway on 9 July 1860. Services from London Victoria stop at Canterbury East and continue to Dover.

Canterbury used to be served by two other stations. North Lane station was the southern terminus of the Canterbury & Whitstable Railway between 1830 and 1846. Canterbury South was on the Elham Valley Railway, which opened in 1890 and closed in 1947.

Road

Canterbury is by-passed by the A2 London to Dover Road. It is about 45 miles (72 km) from the M25 London orbital motorway, and 61 miles (98 km) from central London by road. One of the other main roads through Canterbury is the A28 from Ashford to Ramsgate and Margate.

The City Council has invested in Park and Ride systems around the city's outskirts, with three sites: at Wincheap, New Dover Road and Sturry Road. There are plans to build direct access sliproads to and from the London directions of the A2 where it meets the congested Wincheap (at present there are only slips from the A28 to and from the direction of Dover) to allow more direct access to Canterbury from the A2, but these are currently subject to local discussion. In 2011 a third junction was constructed, linking the A28 to the northbound A2; this leaves just the A2 southbound exit missing, but since this would cut across the Park & Ride car park and meet the A28 at an already complicated junction, it is not expected to be added in the near term.[114]

The hourly National Express 007 coach service to and from Victoria Coach Station, which leaves from the main bus station, is typically scheduled to take two hours. Eurolines coaches run from the bus station to London and Paris.

Stagecoach in East Kent runs most local bus routes in Canterbury as well as long-distance services. The group runs a special 'Unibus' service, with the buses running on 100% bio fuel from the city centre to the University of Kent.[115]

Education

Universities and colleges

The city has an estimated 31,000 students (the highest student/permanent resident ratio in the UK).[116] It is home to three universities, together with several other higher education institutions and colleges; at the 2001 census, 22% of the population aged 16–74 were full-time students, compared with 7% throughout England.[117]

The three universities are: The University of Kent, Canterbury Christ Church University, the University for the Creative Arts.

The University of Kent's main campus is situated over 600 acres (243 ha) on St. Stephen's Hill, a mile north of Canterbury city centre. Formerly called the University of Kent at Canterbury, it was founded in 1965, with a smaller campus opened in 2000 in the town of Chatham. As of 2014, it had around 20,000 students.[118]

Canterbury Christ Church University was founded as a teacher training college in 1962 by the Church of England. In 1978 its range of courses began to expand into other subjects, and in 1995 it was given the power to become a University college. In 2005 it was granted full university status, and as of 2007 it had around 15,000 students.[119]

The University for the Creative Arts is the oldest higher education institution in the city, having been founded in 1882 by Thomas Sidney Cooper as the Sidney Cooper School of Art. Near the University of Kent is the Franciscan International Study Centre,[120] a place of study for the worldwide Franciscan Order. Chaucer College is an independent college for Japanese and other students within the campus of the University of Kent. Canterbury College, formerly Canterbury College of Technology, offers a mixture of vocation, further and higher education courses for school leavers and adults.

Primary and secondary schools

St John's Church of England Primary School was founded as a Board School in 1876. The original neo-Classical school building on St John's Place is now a private house, with the school housed in larger buildings at the end of the street.

Independent secondary schools include Kent College, St Edmund's School and the King's School, the oldest in the United Kingdom. St. Augustine established a school shortly after his arrival in Canterbury in 597, and it is from this that the King's School grew. The documented history of the school only began after the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century, when the school acquired its present name, referring to Henry VIII.[121] The Kings School in Canterbury is one of the top public schools in the United Kingdom, regularly featuring in the top ten most expensive school fees lists.

The city's secondary grammar schools are Barton Court Grammar School, Simon Langton Grammar School for Boys and Simon Langton Girls' Grammar School; all of which in 2008 had over 93% of their pupils gain five or more GCSEs at grades A* to C, including English and maths.[122] The non-selective state secondary schools are The Canterbury High School, St Anselm's Catholic School and the Church of England's Archbishop's School; all of which in 2008 had more than 30% of their pupils gain five or more GCSEs at grades A* to C including English and maths.

Weekend education

The Kent Japanese School (ケント日本語補習校 Kento Nihongo Hoshū Kō), a weekend Japanese educational programme, is held on Saturday mornings on the campus of St. Edmund's School, Canterbury CT2 8HU.[123]

Local media

Newspapers

Canterbury's first newspaper was the Kentish Post, founded in 1717.[28] It changed its name to the Kentish Gazette in 1768[124] and is still being published, claiming to be the country's second oldest surviving newspaper.[125] It is currently produced as a paid-for newspaper produced by the KM Group, based in nearby Whitstable. This newspaper covers the East Kent area and has a circulation of about 25,000.[126]

Three free weekly newspapers provide news on the Canterbury district: yourcanterbury, the Canterbury Times and Canterbury Extra. The Canterbury Times is owned by the Daily Mail and General Trust and has a circulation of about 55,000.[127][128] The Canterbury Extra is owned by the KM Group and also has a circulation of about 55,000.[129] yourcanterbury is published by KOS Media, which also prints the popular county paper Kent on Sunday. It also runs a website giving daily updated news and events for the city.[130]

Radio and television

Canterbury is served by 2 local radio stations, KMFM Canterbury and CSR 97.4FM.

KMFM Canterbury broadcasts on 106FM. It was formerly known as KMFM106, and before the KM Group took control it was known as CTFM, based on the local postcode being CT.[131] Previously based in the city, the station's studios and presenters were moved to Ashford in 2008.[132]

CSR 97.4FM, an acronym for "Community Student Radio", broadcasts on 97.4FM from studios at both the University of Kent and Canterbury Christ Church University. The station is run by a collaboration of education establishments in the city including the two universities. The transmitter is based at the University of Kent, offering a good coverage of the city.[133] CSR replaced two existing radio stations: C4 Radio, which served Canterbury Christ Church University, and UKC Radio, which served the University of Kent.

There are 2 other stations that cover parts of the city. Canterbury Hospital Radio (CHR) serves the patients of the Kent and Canterbury Hospital,[134] and Simon Langton Boys School has a radio station, SLBSLive, which can only be picked up on the school grounds.[135] The city receives BBC One South East and ITV Meridian from the main transmitter at Dover, and a local relay situated at Chartham.

Notable people

People born in Canterbury include:

- Aphra Behn, restoration playwright and novelist

- Orlando Bloom, actor

- Gideon Coe, BBC Radio 6 Music presenter

- Colin Cokayne-Frith, first-class cricketer and British Army officer

- Thomas Sidney Cooper, Victorian animal painter[136]

- Katie Derham, former ITV News journalist, television presenter and BBC Radio 3 presenter

- Nelson Wellesley Fogarty (1871–1933) was the first Bishop of Damaraland (Namibia) from 1924 to 1933.

- Aruhan Galieva, actress and singer

- David Gower,[137] cricketer

- Stephen Gray, 17th/18th-century astronomer, and electricity pioneer was born in Canterbury in 1666.

- William Harvey,[138] physician

- Sir Freddie Laker,[139] airline entrepreneur

- Jack Lawrence, comic book artist

- Thomas James Longley, actor

- Christopher Marlowe,[140]

- W. Somerset Maugham,[138] writer

- Joseph McManners,[141] boy singer and actor

- Fiona Phillips,[142] TV presenter

- Trevor Pinnock,[143] Harpsichordist, conductor, founder of The English Concert.

- Michael Powell,[138] film director and former pupil of The King's School, Canterbury.

- Edmund Reid, detective

- Mary Tourtel, the creator of Rupert Bear,[144] were both born and lived in the city

Notable alumni of the University of Kent include:

- Rosie Boycott, newspaper editor

- Alan Davies, comedian

- Ellie Goulding, singer

- Kazuo Ishiguro,[145] Booker Prize winning novelist

- Chris Simmons

- Tom Wilkinson, actor

In November 2012, Rowan Williams was awarded Freedom of the City for his work as Archbishop of Canterbury between 2003 and 2012.[146]

The grave of author Joseph Conrad, in Canterbury Cemetery at 32 Clifton Gardens, is a Grade II listed building.[147]

International relations

Canterbury is twinned with the following cities:

City to city partnership

Protocol d'accord[149]

.svg.png)

See also

- Province of Canterbury, also known as Archdiocese of Canterbury

- Archbishop of Canterbury – Senior bishop of the Church of England

- Canterbury Christ Church University

- Catching Lives – local charity supporting the homeless and destitute

- List of mayors of Canterbury – Wikimedia list article

- Sheriff of Canterbury

- Mills in Canterbury

- University for the Creative Arts – arts university in southern England

- University of Kent – University based in Kent, United Kingdom

Notes

- "2011 Census - Built-up areas". ONS. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- "Grid Reference Finder". gridreferencefinder.com.

- Roach, Peter; Hartman, James; Setter, Jane; Jones, Daniel, eds. (2006). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (17th ed.). Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-68086-8.

- "Canterbury | The Southeast Guide". Rough Guides. 1 June 1942. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "Girne American University Canterbury". www.gauc.org.uk. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- Lyle 2002, p. 29.

- Hasted, Edward (1800). The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent. XI. Canterbury: W. Bristow. pp. 135–139. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Nennius (attrib.). Theodor Mommsen (ed.). Historia Brittonum, VI. Composed after AD 830. (in Latin) Hosted at Latin Wikisource.

- Ford, David Nash. "[www.britannia.com/history/ebk/articles/nenniuscities.html The 28 Cities of Britain]" at Britannia. 2000.

- "Canterbury Timeline". Channel 4. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- Lyle 2002, p. 16.

- Lyle 2002, pp. 43–44.

- Godfrey-Faussett 1878, p. 29.

- Lyle 2002, p. 42.

- Lyle 2002, pp. 42, 47.

- Lyle 2002, pp. 47–48.

- Lyle 2002, pp. 48–50.

- Lyle 2002, p. 53.

- Peter Sawyer (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. London: Oxford University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-19-285434-6.

- Lyle 2002, pp. 64, 66.

- "Descriptive Gazetteer entry for Canterbury". Vision of Britain. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- "The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer". British Library.

- Lyle 2002, pp. 86–87.

- Lyle 2002, p. 91.

- Lyle 2002, pp. 97–100.

- Lyle 2002, p. 107.

- Lyle 2002, p. 109.

- RM Wiles, Freshest advices: early provincial newspapers in England, Ohio State University Press, 1965, p. 397.

- David J. Shaw and Sarah Gray, ‘James Abree (1691?–1768): Canterbury’s first "modern" printer’, in: The Reach of print: Making, selling and reading books, ed. P. Isaac and B. McKay, Winchester, St Paul’s Bibliographies, 1998. Pp. 21–36. ISBN 1-873040-51-2

- Tatton-Brown, Tim. "Canterbury Castle". Canterbury Archaeological Trust. Archived from the original on 18 January 2010. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- Lyle 2002, p. 110.

- Canterbury, UK: HM Prison Service, archived from the original on 16 February 2008, retrieved 24 September 2008

- Butler 2002, p. 11.

- Ratcliffe, R.L. (1980), Canterbury & Whitstable Railway 1830-1980, Locomotive Club of Great Britain, ISBN 978-0-905270-11-1

- White, H.P. (1961), A Regional History of the Railways of Southern England, Vol. II, London: Phoenix House, pp. 16–8

- Godfrey-Faussett 1878, p. 28.

- Awdry, Christopher (1990), Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies, Sparkford: Patrick Stephens, p. 199, ISBN 978-1-8526-0049-5

- Butler 2002, p. 13.

- Lyle 2002, p. 127.

- https://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/4004161/canterbury,-country-borough/

- Juergensmeyer, Mark; Roof, Wade Clark (2012). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. ISBN 9780761927297.

- BBC. "The restoration of Canterbury Cathedral".

- Butler 2002, p. 14.

- Butler 2002, p. 15.

- Canterbury Archaeological Trust: Previous articles: Big Dig Archived 15 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Butler 2002, p. 16.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link). wikilivres.ca. Retrieved on 25 August 2011.

- Special Collections – Library Services – University of Kent. Library.kent.ac.uk. Retrieved on 25 August 2011.

- "Physical Works".

- "Canterbury Cathedral £25 million restoration leaves it like a building site". 23 June 2018.

- "Background information on the River Stour". kentishstour.org.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Kent & Canterbury Tourist Attraction | Canterbury Historic River Tours. Canterburyrivertours.co.uk. Retrieved on 25 August 2011.

- Lyle 2002, p. 15.

- "Canterbury climate".

- "Weather statistics for Canterbury, England (United Kingdom)".

- "Barton (Ward)". Statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 10 January 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- "Harbledown (Ward)". Statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- "Northgate (Ward)". Statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- "St Stephens (Ward)". Statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- "Westgate (Ward)". Statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- "Wincheap (Ward)". Statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- "Census 2011 result shows increase in population of the South East". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. 16 July 2012. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016.

- "Canterbury Population 2018 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)". worldpopulationreview.com.

- Proposals to the Casino Advisory Panel Archived 28 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Culture.gov.uk. Retrieved on 25 May 2008

- "The Economy – The Canterbury Society". www.canterburysociety.org.uk. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Canterbury's £450 million tourism boost". Canterbury City Council.

- "Universities' £900m impact on the Canterbury economy - University of Kent". The University of Kent.

- Economic Profile 2007 – Canterbury Kent County Council. Retrieved on 25 May 2008 Archived 28 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- https://www.kent.gov.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/8182/District-unemployment-bulletin.pdf

- "Unemployment figures drop". 12 June 2018.

- "UK startup top 40: our ranking of the best places to start a business • Startups Geek". Startups Geek. 20 July 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "Canterbury Cathedral". Canterbury Cathedral. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- "Crumbling cathedral 'needs £50m'". BBC News. 3 October 2006. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- Scheduled monument listing held at Kent County Council

- Lyle 2002, p. 142.

- Tellem 2002, p. 37

- Lyle 2002, pp. 142–147.

- Coles Finch, William (1933). Watermills and Windmills. London: C W Daniel Company. pp. 177–78.

- Canterbury - St Thomas of Canterbury Archived 4 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine from English Heritage, retrieved 29 January 2016

- McCLELLAN, ANDREW (12 December 2007). "MUSEUM STUDIES NOW". Art History. 30 (4): 566–570. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8365.2007.00563.x. ISSN 0141-6790.

- Blower, Nerissa (20 January 2011). "Historic Sites Crumbling". Herne Bay Times. This is Kent. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- Tellem 2002, p. 38.

- The Gulbenkian Theatre, UK: University of Kent, 25 May 2008

- The Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury, Kent, UK, retrieved 25 May 2008

- "The Shakespeare". shakespearecanterbury.co.uk.

- The Canterbury Players: Canterbury's leading amateur dramatics group

- Roger Bowers, 'The Liturgy of the Cathedral and its music, c. 1075–1642', In: A History of Canterbury Cathedral, ed. P. Collinson, N. Ramsay, M. Sparks. (OUP 1995, revised edition 2002), pp. 408–450.

- Canterbury Cathedral: organs and organists.

- James M. Gibson, 'The Canterbury Waits', in: Records of Early English Drama. Kent: Diocese of Canterbury. University of Toronto Press and The British Library, 2002.

- The Canterbury Waits Archived 7 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Themusickcabinet.co.uk (30 July 2011). Retrieved on 25 August 2011.

- Canterbury Cathedral Library Archived 14 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Canterbury-cathedral.org. Retrieved on 25 August 2011.

- "Canterbury Scene". Allmusic. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "University of Kent". Led Zeppelin – Official Website. Archived from the original on 20 December 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "Year 1970". The Who Concert Guide. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "Biography". Ian Dury. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- "27.04.1981 Canterbury – Odeon". The Cure Concerts Guide. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "Joy Division setlist, 16.06.1979". Manchester District Music Archive. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "An Evening with Don McLean". Marlowe Theatre. Archived from the original on 11 December 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "Fairport Convention". Marlowe Theatre. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- Canterbury Choral Society Archived 15 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Mdesignsolutions.co.uk (18 June 2011). Retrieved on 25 August 2011.

- The Canterbury Orchestra. The Canterbury Orchestra (8 January 2010). Retrieved on 25 August 2011.

- "City of Canterbury Chamber Choir".

- University of Kent Music – Making Music. Kent.ac.uk. Retrieved on 25 August 2011.

- Welcome to the Canterbury Festival, Kent's International Arts Festival | Home. Canterburyfestival.co.uk (13 August 2011). Retrieved on 25 August 2011.

- Article on Thomas Clark on West Gallery Music Association web site.

- "St Lawrence Ground". Cricinfo. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- "Canterbury City F.C". Canterbury City F.C. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "A Brief History of Canterbury RFC". Canterbury RFC. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "Tour de France Canterbury". Canterbury City Council. Archived from the original on 26 April 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- About Canterbury Hockey Club Archived 14 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Canterbury Hockey Club. Retrieved on 25 May 2008

- Canterbury. Tourist Guide & Directory. Retrieved on 25 May 2008

- "Kingsmead Leisure Centre – Our Facilities". Active Life. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- Graham Martin, From Vision to Reality: the Making of the University of Kent at Canterbury (University of Kent at Canterbury, 1990) pages 225–231 ISBN 0-904938-03-4

- How to Get Here Archived 16 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine. www.canterbury.co.uk. Retrieved on 25 May 2008)

- Canterbury Times (September 26, 2013). Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- Kentish Gazette 14 May 2015)

- www.statistics.gov.uk, retrieved on 27 May 2008

- "University profile". University of Kent. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- "History of Canterbury Christ Church University". Canterbury Christ Church University. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- Franciscans Archived 6 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine Franciscans.ac.uk. Retrieved on 25 May 2008)

- "A Brief History of the King's School, Canterbury". The King’s School. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- "Secondary schools in Kent: GCSE-level". BBC News. 15 January 2000. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- "欧州の補習授業校一覧(平成25年4月15日現在)" (). Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). Retrieved on 10 May 2014. "The Centerbury Campus Knight Avenue, Canterbury Kent CT2 8QA, United Kingdom"

- KM Group – Over 150 years of history. Kentonline.co.uk. Retrieved on 25 August 2011.

- About the team – Kentish Gazette. Kentonline.co.uk. Retrieved on 25 August 2011.

- "Kentish Gazette". The Newspaper Society and AdWeb Ltd. Archived from the original on 9 February 2006. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- "Canterbury Times". mediaUK. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- "Canterbury Adscene". The Newspaper Society and AdWeb Ltd. Archived from the original on 9 February 2006. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- "Canterbury KM Extra". The Newspaper Society and AdWeb Ltd. Archived from the original on 9 February 2006. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- "yourcanterbury website". KOS Media. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- KMFM 106 Archived 14 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine KMFM Canterbury Website. Retrieved on 30 May 2008.

- Co-location request for KMFM Archived 29 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- CSR 97.4FM. CSR 97.4FM Website. Retrieved on 30 May 2008.

- Hospital radio Archived 9 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Canterbury Hospital Radio. Retrieved on 30 May 2008.

- Simon Langton Grammar School for Boys. Retrieved on 25 May 2008.

- "cooper-ts - Canterbury History". www.canterbury-archaeology.org.uk. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- "David Gower lord of the manor". BBC News. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "Some Famous OKS". The King's School. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- Sir Freddie Laker – British entrepreneur who pioneered low-cost air travel. The Guardian. Retrieved on 29 May 2008

- Christopher Marlowe – Some biographical facts Archived 23 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine at Prestel.co.uk. Retrieved on 29 May 2008)

- Joseph McManners Biography Archived 8 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. JoeMcManners.com Retrieved on 25 May 2008)

- Fiona Phillips Archived 2 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Lycos.com. Retrieved on 29 May 2008

- Aryeh Oron. "Trevor Pinnock (Conductor, Harpsichord)". Archived from the original on 29 July 2003.. Bach Cantatas.com. Retrieved on 16 December 2019

- MARY TOURTEL (1879–1940) Archived 7 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. ChrisBeetles.com. Retrieved on 29 May 2008

- "Kent Alumni". University of Kent. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- "Archbishop of Canterbury receives freedom of city". BBC News. 17 November 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- "Canterbury City Cemetery: Joseph Conrad Memorial". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk.

- Canterbury City Council – Twinning contacts. Retrieved on 14 October 2009. Canterbury.gov.uk (1 March 2011). Retrieved on 25 August 2011.

- Canterbury City Council – International Links. Retrieved on 17 January 2011 Archived 4 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

References

- Butler, Derek (2002), A Century of Canterbury, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7509-3243-1

- Lyle, Marjorie (2002), Canterbury: 2000 Years of History, Tempus, ISBN 978-0-7524-1948-0

- Tellem, Geraint (2002), Canterbury and Kent, Jarrold Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7117-2079-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canterbury. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Canterbury. |

- , Encyclopædia Britannica, 5 (11th ed.), 1911, pp. 210–212

- Canterbury City Council

- Canterbury Buildings website – Archaeological and heritage site of Canterbury's buildings.

- Canterbury Archaeological Trust – Whitefriars excavations

- TimeTeam: Canterbury Big Dig

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre – World Heritage profile for Canterbury.