Canterbury city walls

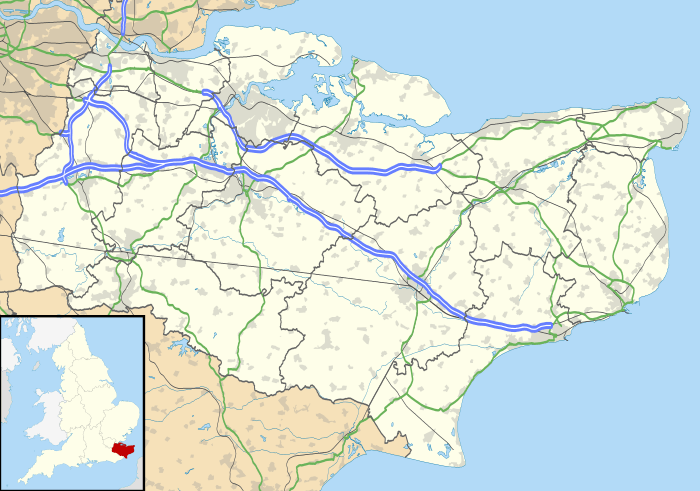

Canterbury city walls are a sequence of defensive walls built around the city of Canterbury in Kent, England. The first city walls were built by the Romans, probably between 270 and 280 AD. These walls were constructed from stone on top of an earth bank, and protected by a ditch and wall towers. At least five gates were placed into the walls, linked to the network of Roman roads across the region. With the collapse of Roman Britain, Canterbury went into decline but the walls remained, and may have influenced the decision of Augustine to settle in the city at the end of the 6th century. The Anglo-Saxons retained the defensive walls, building chapels over most of the gates and using them to defend Canterbury against Viking incursions.[1]

| Canterbury city walls | |

|---|---|

| Canterbury, Kent, England | |

Canterbury city walls | |

Canterbury city walls | |

| Coordinates | 51.28142°N 1.07567°E |

| Type | City wall |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Ragstone, flint |

| Events | Viking expansion Peasants' Revolt Jack Cade's Rebellion English Civil War |

The Norman invaders of the 11th century took the city without resistance, and by the 12th century the walls were ill-maintained and of little military value. Fears of a French invasion during the Hundred Years' War led to an enquiry into Canterbury's defences in 1363. The decision was taken to restore the city walls and for around the next thirty years the old Roman defences were freshly rebuilt in stone, incorporating the older walls where they still remained. 24 towers were constructed around the circuit, and over the coming years many of the gatehouses were rebuilt in stone and brick, defended by some of the first batteries of guns in England. Parts of the wall were deliberately damaged by Parliament during the English Civil War of the 17th century and the doors to the city's gates burnt; with the restoration of Charles II in 1660, new doors were reinstalled.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Canterbury's city walls came under extensive pressure from urban development. All the gates but one, West Gate, were destroyed and extensive parts of the walled circuit were knocked down to make way for new roads and buildings. German bombing during the Second World War caused further damage. Despite this, the remaining walls and gatehouse survived post-war redevelopment intact and some portions were rebuilt entirely. Over half the original circuit survives, enclosing an area of 130 acres (53 ha), and archaeologists Oliver Creighton and Robert Higham consider the city wall to be "one of the most magnificent in Britain".[2]

History

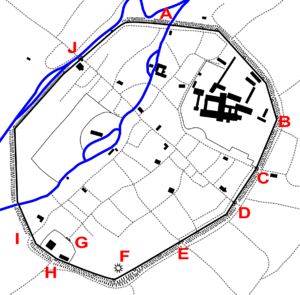

3rd–4th centuries

The first city walls in Canterbury were built by the Romans.[3] Canterbury, then called Duverovernum Cantiacorum, was initially probably defended by a small fort but had not required any other civic defences.[4] The security situation in Britain deteriorated in the late 3rd century AD and a circuit of defensive walls were built around the city, probably between 270 and 290.[5] They enclosed an area of 130 acres (53 ha), cutting off the old industrial parts of the western side of the city, but incorporating a cemetery area to the south-east that had formerly been outside the city boundary.[6] New coastal forts were also built across the region at around the same time, and a headquarters for them may have been established in Canterbury.[7]

The walls were typically 7.5 feet (2.3 m) inches thick and built of flint and mortar, with some limited use of larger sandstone blocks.[3] The height of these walls is uncertain, but sections have survived that are up to 20 feet (6.1 m) high.[8] The walls stood on a bank of earth between 20 feet (6.1 m) and 30 feet (9.1 m) wide and at least 7 feet (2.1 m) high, protected by a ditch, typically 59 feet (18 m) wide and 16.5 feet (5.0 m) deep, but in places up to 82 feet (25 m) wide.[9] A 10 feet (3.0 m) wide cobbled berm ran between the ditch and the wall.[10]

The walls had at least five gates, typically positioned near angles in the city wall, although, judging from the location of Roman roads, it is possible that another two Roman gates may also have existed.[11] The gates linked to the network of major roads that ran across Kent.[12] The Riding Gate, which took its name from the red bricks with which it was built, had two protective towers and a pair of entrance arches for pedestrians and carriages, as probably did Burgate.[13] The Worth Gate, the London Gate and the Queningate had simpler entrance arches.[14] A sequence of square towers protected the walls, and at least one additional wall tower was constructed following the Saxon invasion of Britain in 367.[14]

5th–11th centuries

During the 5th century, Canterbury went into decline and its Roman institutions and buildings crumbled, although the city walls survived.[15] In 597, Augustine was sent to Kent by Pope Gregory I to convert the local population to Christianity.[16] Augustine established Canterbury Cathedral within the city, possibly because the walled site gave them additional protection or because it was symbolically important as a former Roman city.[17] Canterbury, now called Cantwaraburh, prospered and its population and trade increased.[18] Much of the land within the walls had become water meadows and farmland, and an palisade may have built around the cathedral and its precinct to form a secure inner stronghold.[19]

In the late Anglo-Saxon period, the internal street layout of Canterbury was remodelled, but the line of the outer walls remained the same.[20] A cattle market was created outside the city to the south-east, and Newingate, later renamed St George's Gate, was inserted into the walls to allow easy access to it.[21] During this the period the main axis of the city shifted from the older line of streets running from London Gate and Riding Gate, to the new route between West Gate and Newingate.[22] A lane was built running around the inside of the walls, in a similar way to the intramural streets built around the same time at Exeter and Winchester.[23] Churches and chapels were built over the gates, including St Mary's above the North Gate; the Holy Cross over West Gate; St Michael's over Bargate; St Edmund's within Riding Gate; and, potentially, St George's Chapel over Newingate.[24] Canterbury's walls were mentioned by the early chronicler, Bede, in his history of England.[25]

Despite Canterbury's walls, a Viking army successfully attacked the city in 835, killing many of the inhabitants.[26] Scandinavian raids recommenced from 991 onwards and in 1011 a Danish army demanded fresh tribute from the city.[26] The city walls were used to defend the city during an 11-day siege, and the chronicler Roger of Hoveden recounts how the attacking Danes were thrown off the tops of the walls to their deaths by the citizens.[27] Roger's account may be an exaggeration, but the story shows that the city walls were in sufficiently good condition for such a story to be considered plausible at the time.[28] After a fire broke out in the city, however, the Danes entered and pillaged Canterbury.[29]

11th–13th centuries

The inhabitants of Canterbury put up no resistance to the Normans during their conquest of England in 1066.[30] William the Conqueror instructed that a castle was to be built in the city; Canterbury Castle was built on the south side of the city and formed part of the circuit of defence, with property being destroyed to make room for it.[31] Despite its location along the walls, archaeologists Oliver Creighton and Robert Higham have observed that the castle was not an "addition" to the defences, but more an "imposition" on the town within it.[32] The first timber motte and bailey castle was later abandoned and a second, with a square, stone keep, built in 1123.[33] The Worth Gate became the south entrance to the castle site, and a new gate was put into the walls to the east for general use.[34]

In 1086, the Domesday Book recorded that 11 houses had been built in the ditches around the city walls, which by then appear to have been in a poor condition.[27] The encroachment was possibly the result of population pressures on the inner, walled city, as Canterbury had spread out well beyond the walls by the mid-11th century.[35] It is unclear how the walls were maintained during this period, and by the 12th century they were in ruins and of little practical defensive value.[36] In the late-12th century, the walls were assigned some limited royal funding through the local sheriff, probably for the maintenance of existing structures, and just over £5 was spent in 1166–67 on these repairs.[37]

Wooden "bars" had been placed outside many of the city gates to regulate the flow of traffic by the 12th century, including Riding Gate, Worth Gate and North Gate.[38] One area of the city beyond the wall, called the baggeberi, may also have been protected by its own earthworks during the middle of the 12th century.[39] Canterbury was divided into wards by the 12th century, although these may potentially have been created as early as the Anglo-Saxon period.[40] These administrative districts, named after the city gates, were termed berthae and were linked to maintenance and manning of the city walls.[41] The wards took the form of segments, spreading out from the centre of the city, incorporating the relevant gate and sometimes the suburbs beyond that had spread outside the walls.[42] By the 1160s Canterbury's wards included Burgate, Northgate and Newingate, with the wards of Riding Gate, Worthgate and West Gate being formed by the end of the century.[42]

After the 12th century, work on the walls appears to have stopped until the second half of the 14th century.[43] The city walls fell further into disrepair as a result.[44] In some places, over 1 foot (0.30 m) of debris came to cover the remaining stonework of the old Roman walls, while in another case a building was constructed directly over the top of the former defences.[44]

14th century

In the early 1360s, during the Hundred Years War, there was an increased level of concern about potential French raids or invasion along the south of England.[45] Canterbury was particularly important for the defence of the south-east, as it formed a potential barrier to any invaders marching on London.[46] An enquiry was carried out in 1363 into the state of Canterbury's defences, which concluded that the city was in a parlous position, as "the walls of Canterbury are for the most part fallen because of age, and the stones thereof carried away, and the ditches under the walls are obstructed".[43]

Canterbury's bailiffs were ordered to repair the walls, with similar instructions being issued to the authorities in vulnerable cities such as Colchester, Bath and Rochester.[47] The result was what historian Hilary Turner has described as a "well-planned operation", designed to build the walls rapidly, but which still took around 30 years to complete.[48] The city and the cathedral authorities worked closely together on the project, an unusual situation, given the local political tensions that existed between them.[49]

Money was needed to pay for this work. During the previous century, a method of taxation had been introduced to support the creation or maintenance of city walls, called murage, which was authorised by the king and applied to trade entering a city.[50] In total, Canterbury was assigned 31 years of murage grants for its walls, starting in 1378, when five years of murage was granted by Richard II, along with a writ allowing them to use stonemasons from across the county.[51] In 1379, a new 10-year murage grant was issued.[43] In 1385, £100 from the issues of Kent was given to Canterbury, and the murage tax extended for a further five years.[52] In the financial year of 1385–86, approximately £619 was spent on the walls.[52] Despite the walls, during the Peasants Revolt of 1381, Wat Tyler and his army were able to enter Canterbury unopposed.[53] 1399 saw another five years of murage granted, followed in 1402 by a final grant of three years.[52]

Despite this, progress was not fast enough to suit the royal authorities. Richard II ordered the city to force workmen to repair the defences, and intervened in Canterbury's local elections in 1387 to ensure that two trusted bailiffs – Henry Lincoln and John Proude – were returned to office, in order for the King to have confidence in the walls being maintained.[54][nb 1] In 1403, Henry IV sent messages to the city complaining that the defences were not being adequately maintained, and that the city was still insecure.[55]

15th–16th centuries

A survey in 1402 suggested that most of the city was walled, except for part of the stretch between the West Gate and North Gate.[52] In 1409, the city's bailiffs were allowed to acquire lands worth £20 a year to support the maintenance of the walls, and Canterbury was permitted to draw funding from the royal customs duties for the walls.[56] Murage taxes in Canterbury gave way to the introduction of support through a system of rates, with each ward being tasked to raise money through local taxes on its citizens.[57] The walls became an important symbol of the city, and 15th-century art from Canterbury presents the cathedral and the city wall as having equal status as key features of the city.[58]

The resulting circuit of walls followed the line of the former Roman and Anglo-Saxon defences, incorporating them where they survived in good condition. Parts of the 14th century walls, for example along Burgate Lane, have been shown to 4 feet (1.2 m) thick at the base and built of Kentish ragstone; other sections incorporated the original Roman wall, which was still up to 8 feet (2.4 m) high in places.[59] The new walls had a continuous wall walk and were crenellated.[60] Most of the circuit was protected by an external ditch.[61] The city walls retained the older system of Roman and Anglo-Saxon gates. West Gate was rebuilt around 1380 by the prominent mason, Henry Yevele, an unusually prominent architect for a city wall programme.[62] As part of this work, Holy Cross Church was moved from over the gate to a nearby site.[63] The old Roman Riding Gate was cut through by a new archway.[14]

Defensive towers were built around the city walls, and archaeological and historical evidence suggests that there were 24 of these.[64] The towers had a generally uniform appearance, with 16 half-circular, or "horse-shoe", hollow-backed towers and eight square towers.[65] The horse-shoe towers followed a fashion that had been popular from around 1260 to 1390, making Canterbury's towers a late example of the trend.[66] The square towers were a newer design, and were built around the turn of the 14th and 15th century by Thomas Chillenden of Christchurch Priory.[67]

The reconstructed walls also saw the introduction of gunports.[68] West Gate was an innovative piece of defensive design in this regard, forming a powerful battery, carefully designed to have a wide angle of covering fire.[69] Positioning of the gunloops is similar to those at Cooling Castle, built around the same time, and gave particular focus to the left flank along North Gate, the most likely route for any attackers.[70] Gunports in south-west corner of the city walls are put at alternate heights, for overlapping fire.[71] The first documentary record of Canterbury's guns appears in 1403, when it is clear that there were several kept in the West Gate.[72]

A second wave of work took place on the city walls in the late 15th century.[73] Backed by substantial communal effort and financial contributions, Newingate was rebuilt between 1450 and 1470, and probably closely resembled the West Gate in style.[74] Burgate was rebuilt in brick from 1475 onwards, again thanks to public contributions, but it was not completed until 1525, furnished with gunports and anachronistic battlements.[75] Queningate was closed up at shortly after the 15th century, probably following the construction of a new postern gate nearby.[14] West Gate was appointed the city gaol in 1453 by Henry VI, with Canterbury Castle serving as the county gaol.[63]

In contrast to Wat Tyler's entrance in 1381, in 1450, Jack Cade and 4,000 rebels were barred entry from the city at West Gate.[53] In 1533, Canterbury reacted with concern to the news of Thomas Wyatt's rebellion in Kent; repairs were made to the walls, guns and ammunition mobilised, and the Riding Gate was blocked up.[76] Queen Mary later thanked the city for their efforts.[77]

17th–19th centuries

By 1614, the ditch outside the walls appears to have been partially filled in and the reclaimed land rented out.[78] During the English Civil War, Canterbury was initially held by Parliamentary forces.[79] In 1647, however, riots broke out in protest over the actions of the city's Puritan mayor and Canterbury declared its loyalty for Charles I.[79] Parliamentary forces intervened and reoccupied the city, burning the wooden city gates and deliberately damaging, or slighting, the walls near Canterbury Castle.[79] With the restoration of Charles II to the throne in 1660, new wooden doors were installed at the West Gate.[63]

Towards the end of the 18th century, horse-drawn coaches became much more common in Canterbury, which lay at the centre of a new turnpike road system.[80] This required extensive changes to the city streets and gateways, which were typically too narrow to be easily navigated by these vehicles.[81] By 1779, Northgate and Burgate had been destroyed to allow wider entrances for the city.[82] Riding Gate was demolished in 1782, but in 1791 the local citizen James Simmons built a new, brick archway on the old foundations, which was rapidly occupied by a new house, blocking most of the gateway.[83] An iron bridge was later built over the site of Riding Gate.[84] The Worth Gate was demolished in 1791 and reused in a local garden, a new entrance being built in its place.[85] Newingate's drum towers were used as a water reservoir for the city, and the gatehouse was not demolished until 1801.[86] Sections of the wall were cut away to allow new roads to be built; the walls near St Radiguns's Public Baths were demolished in 1794 and the city wall around London Gate was demolished around 1800.[87]

In other parts of Canterbury, the city walls became used for promenades by the more fashionable citizens.[88] The Dane John Gardens were built between 1790 and 1803 by Simmons in the south-east corner of the walls, remodelling the old castle motte, and incorporating the Roman bank and the medieval wall-walk into the design.[89] The ownership of the land was disputed, and the park was taken into the control of the city shortly after its construction.[90]

West Gate continued to be used as the city gaol, resulting in it surviving the destruction of the other city gates.[91] When the reformer John Howard visited the gaol in the mid-1770s, he noted that it contained a large day room for male and female prisoners and two small night rooms, but no courtyard for exercise.[92] Prison reform became an important issue during the early 19th century, and the West Gate gaol was considered unsatisfactory, being condemned as dirty, cramped and insecure, resulting in the extension of the gaol into Pound Lane and the consequent dismantling of the adjacent city wall.[93] There was a legal attempt to demolish the West Gate altogether in 1859, in order to allow the Wombwell Circus to march a parade of elephants into the city; the gatehouse was only saved by the casting vote of Canterbury's mayor.[94] In 1865 the prison was closed and the West Gate became used first for the storage of archives and then as a museum.[63]

20th–21st centuries

During the Second World War, part of the city walls near the Dane John Gardens were turned into an ammunition depot, dug into the bank of the wall.[90] German bombing campaigns in 1942 caused extensive damage to Canterbury, including the city walls around Riding Gate.[84] The bomb damage provided fresh opportunities for archaeological investigation, however, and work by the Canterbury Excavation Committee began in 1944.[95] This research disproved older theories about the shape of the Roman city walls, demonstrating that the Roman and medieval defences formed an identical circuit.[95]

In the post-war years, the city walls shaped the route of Canterbury's modern ring road system, protecting the inner core of the ancient city, despite proposals under the Holden Plan of 1945 for a radical reshaping of the city's road network.[96] During the 1950s, a stretch of Canterbury's walls were reconstructed, including two circular towers, as part of the redevelopment of the St George district.[94] In the early 1980s, the volume of traffic around the West Gate was causing damage to the structure of the building.[97] The remaining walls and West Gate are protected under UK law as scheduled monuments and as a Grade I listed building.

Architecture

Canterbury's city walls in the 21st century are a mixture of survivals from the multiple periods of building, from Roman to the 20th century, but the majority of the visible walls are medieval in origin.[98] Over half the original circuit survives, and archaeologists Oliver Creighton and Robert Higham consider it "one of the most magnificent in Britain".[2] Of the original 24 medieval towers along the walls, 17 remain intact, and one entranceway into the city, the West Gate, also survives.[61]

North Gate was destroyed in the 19th century, but its former location is marked by a "Cozen Stone", a marker laid down by amateur archaeologist Walter Cozens in the interwar years.[99] Moving clockwise around the circuit from Northgate, St Mary's Church incorporates parts of the walls into its structure, and the original medieval crenellations can be seen in the stonework.[2] Four square towers survive around the walls here, mostly somewhat reduced in height from their original medieval form, and with their gunports converted to windows.[82] The outline of Queningate is marked out on the local road, and parts of the Roman wall discovered in archaeological investigations are presented in a local display.[100] A further two towers beyond Queningate survive, complete with their original gunports.[82] The former site of Burgate is marked by another Cozen Stone, and on the next stretch of wall, one tower survives, used for a period as a water cistern and now incorporated into the 19th century Zoar Chapel.[101]

The south-east stretch of the walls beyond the former site of Riding Gate, marked by a 19th-century plaque, are particularly well preserved, including the Dane John Gardens, used as a public park and decorated with sculptures.[102] The two towers near this stretch of wall are reconstructions from the 1950s on the original medieval foundations.[103] Another four towers survive between the former sites of Riding Gate and Wincheap Gate, one of which remains near its original height and retains its defensive crenellations.[103] Beyond the former site of Wincheap Gate the wall has mostly been destroyed, although one tower survives, converted into a private house; the former site of Worth Gate is marked by a memorial stone.[104]

The West Gate has survived in excellent condition, and Creighton and Higham describe it as "one of the most monumental of all examples of town gate architecture".[105] Constructed from ragstone and flint, it has two large circular towers at the front, but has a square-facing interior; although fireplaces were built into each tower in the 14th century, their flues were designed to be hidden from sight so as not to spoil its military appearance.[106] The West Gate hosts a local museum and cafe.[63] A final three towers survive on the stretch of the walls between West Gate and the former North Gate.[82]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canterbury city walls. |

- List of town walls in England and Wales

- Southampton city walls

References

Notes

- The King's intervention in the elections in this way was unusual, only occurring in Canterbury, Southampton, Winchester and Sandwich.[52]

References

- Julian D. Richards. Viking Age England. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-7524-2888-8.

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 259

- Frere & Stow 1982, p. 17

- Lyle 2002, pp. 29–31

- Lyle 2002, pp. 43–44

- Lyle 2002, p. 20; Frere & Stow 1982, p. 17

- Lyle 2002, p. 46

- Lyle 2002, p. 44

- Frere & Stow 1982, p. 20; Lyle 2002, p. 44

- Lyle 2002, p. 20

- Frere & Stow 1982, pp. 19–20, 51; Lyle 2002, p. 44

- Lyle 2002, pp. 21–23

- Frere & Stow 1982, p. 19; Lyle 2002, p. 44; "Riding Gate", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013.

- Frere & Stow 1982, p. 19

- Lyle 2002, pp. 40–42

- Lyle 2002, pp. 47–48

- Creighton & Higham 2005, pp. 55–56; Lyle 2002, pp. 47–48

- Lyle 2002, p. 51

- Lyle 2002, p. 50; Fleming 2011, p. 186

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 44

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 45

- Lyle 2002, p. 24

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 52

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 177; "Riding Gate", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013.

- Frere & Stow 1982, p. 21

- Lyle 2002, p. 53

- Turner 1971, p. 21

- Turner 1971, pp. 22, 148; Frere & Stow 1982, p. 21

- Lyle 2002, pp. 53–54

- Lyle 2002, p. 56

- Turner 1971, p. 55; Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 68; Lyle 2002, p. 64

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 69

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 70; Lyle 2002, p. 65

- Frere & Stow 1982, p. 56

- Creighton & Higham 2005, pp. 65, 95

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 65; Turner 1971, p. 151

- Turner 1971, pp. 23, 151

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 90

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 95

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 185; Lyle 2002, p. 56

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 184; Lyle 2002, p. 56

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 188

- Turner 1971, p. 148

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 67

- Turner 1971, pp. 41–42, 81; Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 203

- Turner 1971, p. 82

- Turner 1971, p. 81

- Turner 1971, p. 15; Frere & Stow 1982, p. 21

- Turner 1971, p. 150

- Turner 1971, pp. 28–31

- Turner 1971, pp. 148, 150

- Turner 1971, p. 149

- Lyle 2002, p. 91

- Turner 1971, pp. 49, 81, 149

- Turner 1971, pp. 81–82

- Turner 1971, pp. 43, 150

- Turner 1971, p. 40

- Turner 1971, p. 92

- Turner 1971, p. 151

- Turner 1971, pp. 62–63

- Turner 1971, p. 152

- Turner 1971, p. 47

- "Westgate", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013.

- Frere & Stow 1982, p. 23

- Frere & Stow 1982, p. 23; Turner 1971, p. 58

- Turner 1971, p. 58

- Turner 1971, p. 60; Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 139

- Turner 1971, pp. 65–66

- Turner 1971, p. 66; Creighton & Higham 2005, pp. 37, 114

- Frere & Stow 1982, p. 117

- Turner 1971, p. 66

- Turner 1971, p. 84

- Frere & Stow 1982, p. 22

- Turner 1971, p. 154; Frere & Stow 1982, p. 22; Lyle 2002, p. 89

- Turner 1971, p. 153; Lyle 2002, p. 89

- "Riding Gate", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013; Cox 1905, p. 107

- Cox 1905, p. 107

- Frere & Stow 1982, p. 96

- Lyle 2002, p. 109

- Lyle 2002, p. 110

- Lyle 2002, p. 111

- Turner 1971, p. 153

- Frere & Stow 1982, p. 19; "Riding Gate", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013.

- "Riding Gate", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013.

- Frere & Stow 1982, pp. 19, 56

- Turner 1971, p. 154; Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 240

- Frere & Stow 1982, pp. 28, 97

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 241

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 242; "Dane John Gardens", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013.

- "Dane John Gardens", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013.

- Creighton & Higham 2005, pp. 171, 239

- Howard 1777, p. 226

- Brent 1860, p. 26; "Westgate", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013.

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 243

- Lyle 2002, p. 129

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 243; Lyle 2002, pp. 128–129

- Frere & Stow 1982, p. 107

- Creighton & Higham 2005, pp. 40, 259

- "Dane John Gardens", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013; "Cozens' Paving Stones", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013.

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 259; "St George's Gate", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013.

- Turner 1971, p. 154; Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 259; "Zoar Chapel", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013; "Burgate", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013.

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 259; "Dane John Gardens", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013; "Riding Gate", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013.

- Turner 1971, p. 154

- Turner 1971, p. 154; "Worth Gate", Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, retrieved 29 March 2013.

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 193; Turner 1971, p. 152.

- Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 114; Turner 1971, p. 152; Frere & Stow 1982, p. 111

Bibliography

- Brent, John (1860). Canterbury in the Olden Time: From the Municipal Archives and Other Sources. Canterbury, UK and London, UK: A. Ginder, and Bell and Daldy. OCLC 6386983.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cox, J. Charles (1905). Canterbury, a Historical and Topographical Account of the City. London, UK: Methuen. OCLC 185430872.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Creighton, Oliver; Higham, Robert (2005). Medieval Town Walls: an Archaeology and Social History of Urban Defence. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-1445-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fleming, Robin (2011). Britain After Rome: The Fall and Rise, 400 to 1070. London, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-014823-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frere, S. S.; Stow, Sally (1982). "The Defensive Circuit". In Frere, S. S.; Stow, Sally; Bennett, P. (eds.). Excavations on the Roman and Medieval Defences of Canterbury. Maidstone, UK: Canterbury Archaeological Trust and Kent Archaeological Society. pp. 17–120. ISBN 0-906746-03-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howard, John (1777). The State of the Prisons in England and Wales, with Preliminary Observations and an Account of Some Foreign Prisons. Warringon, UK: William Eyres. OCLC 24425499.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lyle, Marjorie (2002). Canterbury: 2000 Years of History (Revised ed.). Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-1948-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turner, Hilary L. (1971). Town Defences in England and Wales. London, UK: John Baker. OCLC 463160092.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)