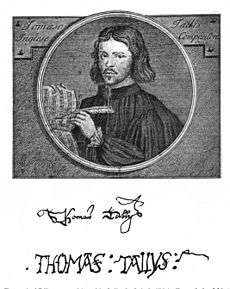

Thomas Tallis

Thomas Tallis (c. 1505 – 23 November 1585)[lower-alpha 1] was an English composer who occupies a primary place in anthologies of English choral music. He is considered one of England's greatest composers, and he is honoured for his original voice in English musicianship.[2] No contemporaneous portrait of Tallis survives; the one painted by Gerard Vandergucht dates from 150 years after Tallis died, and there is no reason to suppose that it is a fair likeness. In a rare existing copy of his blackletter signature, he spelled his name "Tallys".[3]

Life

Early years

Little is known about Tallis's early life. He was born in the early 16th century toward the end of Henry VII's reign. The name "Tallis" is derived from the French word taillis, which means a "thicket." There are suggestions that he was a child of the chapel (boy chorister) of the Chapel Royal, the same singing establishment which he joined as an adult.[4]

Tallis's first known musical appointment was in 1532 as organist of Dover Priory (now Dover College), a Benedictine priory in Kent.[5] His career took him to London, then to Waltham Abbey in the autumn of 1538, a large Augustinian monastery in Essex which was dissolved in 1540. He was paid off and acquired a book about music that contained a treatise by Leonel Power which prohibits consecutive unisons, fifths, and octaves.[4]

.jpg)

Tallis's next post was at Canterbury Cathedral. He was sent to Court as a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal in 1543, where he composed and performed for Henry VIII,[6] Edward VI (1547–53), Mary I (1553–58), and Elizabeth I, until he died in 1585.[7]

Tallis avoided the religious controversies that raged around him throughout his service to successive monarchs, though he remained an "unreformed Roman Catholic", in the words of Ackroyd 2002, p. 184. Tallis was capable of switching the style of his compositions to suit the different monarchs' vastly different demands.[8] He stood out among other important composers of the time, including Christopher Tye and Robert White. Walker observes that "he had more versatility of style" than Tye and White, and "his general handling of his material was more consistently easy and certain."[9] Tallis was also a teacher of William Byrd and of Elway Bevin, an organist of Bristol Cathedral and Gentleman of the Chapel Royal.[10] Tallis married around 1552, and his wife Joan outlived him by four years. They apparently had no children. Late in his life, he lived in Greenwich, possibly close to the royal palace; tradition holds that he lived on Stockwell Street.[11]

Work with William Byrd

.jpg)

Queen Mary granted Tallis a lease on a manor in Kent which provided a comfortable annual income.<[12]

In 1575, Queen Elizabeth granted him and William Byrd a 21-year monopoly for polyphonic music[13] and a patent to print and publish music, which was one of the first arrangements of that type in the country.[14] Tallis's monopoly covered "set songe or songes in parts", and he composed in English, Latin, French, Italian, and other languages, as long as they served for music in the church or chamber.[13] Tallis had exclusive rights to print any music in any language, and he and Byrd were the only ones allowed to use the paper that was used in printing music. They used their monopoly to produce Cantiones quae ab argumento sacrae vocantur in 1575, but the collection did not sell well and they appealed to Queen Elizabeth for her support.[13] People were naturally wary of their new publications, and it did not help that they were both avowed Roman Catholics.[14] They were also forbidden to sell any imported music. Lord points out that they were not given "the rights to music type fonts, printing patents were not under their command, and they didn't actually own a printing press."[15]

Tallis retained respect during a time of religious and political upheaval, and he avoided the violence which claimed Catholics and Protestants alike.[16]

Death

Tallis died in his house in Greenwich in November 1585; most historians agree that he died on 23 November, though one source gives the date as 20 November.[17][18] He was buried in the chancel of the parish of St Alfege Church, Greenwich, though the exact location in the church is unknown. His remains may have been discarded by labourers between 1712 and 1714 when the church was rebuilt, and nothing remains of Tallis's original memorial in the church. John Strype found a brass plate in 1720 which read:

Entered here doth ly a worthy wyght,

Who for long tyme in musick bore the bell:

His name to shew, was THOMAS TALLYS hyght,

In honest virtuous lyff he dyd excell.

He serv’d long tyme in chappel with grete prayse

Fower sovereygnes reygnes (a thing not often seen);

I meane Kyng Henry and Prynce Edward’s dayes,

Quene Mary, and Elizabeth oure Quene.

He mary’d was, though children he had none,

And lyv’d in love full thre and thirty yeres

Wyth loyal spowse, whose name yclypt was JONE,

Who here entomb’d him company now beares.

As he dyd lyve, so also did he dy,

In myld and quyet sort (O happy man!)

To God ful oft for mercy did he cry,

Wherefore he lyves, let deth do what he can.[19]

William Byrd wrote the musical elegy Ye Sacred Muses on Tallis's death.

Liturgical calendar

Tallis is honoured with a feast day, together with William Byrd and John Merbecke, on the liturgical calendar of the American Episcopal Church on 21 November.

Works

Early works

The earliest surviving works by Tallis are Salve intemerata virgo, Ave rosa sine spinis and Ave Dei patris filia, both devotional antiphons to the Virgin Mary which were sung in the evening after the last service of the day; they were cultivated in England at least until the early 1540s. Henry VIII's break from the Roman Catholic church in 1534 and the rise of Thomas Cranmer noticeably influenced the style of music being written. Cranmer recommended a syllabic style of music where each syllable is sung to one pitch, as his instructions make clear for the setting of the 1544 English Litany.[20] As a result, the writing of Tallis and his contemporaries became less florid. Tallis' Mass for Four Voices is marked with a syllabic and chordal style emphasising chords, and a diminished use of melisma. He provides a rhythmic variety and differentiation of moods depending on the meaning of his texts.[21]

The reformed Anglican liturgy was inaugurated during the short reign of Edward VI (1547–53),[22] and Tallis was one of the first church musicians to write anthems set to English words, although Latin continued to be used alongside the vernacular.[23] Mary Tudor set about undoing some of the religious reforms of the preceding decades, following her accession in 1553. She restored the Roman Rite, and compositional style reverted to the elaborate writing prevalent early in the century.[24] Two of Tallis's major works were Gaude gloriosa Dei Mater[25] and the Christmas Mass Puer natus est nobis, and both are believed to be from this period. Puer natus est nobis based on the introit for the third Mass for Christmas Day may have been sung at Christmas 1554 when Mary believed that she was pregnant with a male heir.[26] These pieces were intended to exalt the image of the Queen, as well as to praise the Virgin Mary.[24]

Some of Tallis's works were compiled by Thomas Mulliner in a manuscript copybook called The Mulliner Book before Queen Elizabeth's reign, and may have been used by the queen herself when she was younger. Elizabeth succeeded her half-sister in 1558, and the Act of Uniformity abolished the Roman Liturgy[2] and firmly established the Book of Common Prayer.[27] Composers resumed writing English anthems, although the practice continued of setting Latin texts among composers employed by Elizabeth's Chapel Royal.

The religious authorities at the beginning of Elizabeth's reign being protestant, tended to discourage polyphony in church unless the words were clearly audible or, as the 1559 Injunctions stated, "playnelye understanded, as if it were read without singing".[28] Tallis wrote nine psalm chant tunes for four voices for Archbishop Matthew Parker's Psalter published in 1567.[29] One of the nine tunes was the "Third Mode Melody" which inspired the composition of Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis by Ralph Vaughan Williams in 1910.[30] His setting of Psalm 67 became known as "Tallis's Canon", and the setting by Thomas Ravenscroft is an adaptation for the hymn "All praise to thee, my God, this night" (1709) by Thomas Ken,[31] and it has become his best-known composition. The Injunctions, however, also allowed a more elaborate piece of music to be sung in church at certain times of the day,[28] and many of Tallis's more complex Elizabethan anthems may have been sung in this context, or alternatively by the many families that sang sacred polyphony at home.[32] Tallis's better-known works from the Elizabethan years include his settings of the Lamentations (of Jeremiah the Prophet)[12] for the Holy Week services and the unique motet Spem in alium written for eight five-voice choirs, for which he is most remembered. He also produced compositions for other monarchs, and several of his anthems written in Edward's reign are judged to be on the same level as his Elizabethan works, such as "If Ye Love Me".[33] Records are incomplete on his works from previous periods; 11 of his 18 Latin-texted pieces from Elizabeth's reign were published, "which ensured their survival in a way not available to the earlier material".[34]

Later works

Toward the end of his life, Tallis resisted the musical development seen in his younger contemporaries such as William Byrd, who embraced compositional complexity and adopted texts of disparate biblical extracts.[35] Tallis was content to draw his texts from the Liturgy[2] and wrote for the worship services in the Chapel Royal.[2] He composed during the conflict between Catholicism and Protestantism, and his music often displays characteristics of the turmoil.[36]

Fictional portrayals

A fictionalised Thomas Tallis was portrayed by Joe Van Moyland in 2007 on the BBC television series The Tudors.[37]

References

Notes

- 3 December 1585 by the Gregorian calendar

Citations

- Cole 2008, pp. 212–226.

- Farrell 2001, p. 125.

- Cole 2008b, p. 62.

- Walker 1907, p. 34.

- Lord & Brinkman 2003, p. 197.

- Holman 1999, p. 201.

- Thomas 1998, p. 136.

- Phillips 2005, p. 8.

- Walker 1907, p. 44.

- Walker 1907, p. 56.

- Paul Doe/David Allinson, Grove online.

- Cole 2008b, p. 93.

- Holman 1999, p. 1.

- Lord & Brinkman 2003, p. 69.

- Lord & Brinkman 2003, p. 70.

- Gatens. "Tallis: Works, all." American Record Guide 68.3 (May–June 2005): 181.

- Harley, John (2015). Thomas Tallis. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate. p. 212. ISBN 9781317010364.

- Rimbault, Edward F. (1872). The Old Cheque-Book or Book of Remembrance of The Chapel Royal from 1561 to 1744, J.B, Nichols and Sons, p. 192.

- Rimbault 192–193.

- Willis, Jonathan P. Church Music and Protestantism in Post-Reformation England, Ashgate, 2010, p. 52.

- Manderson, Desmond. Songs Without Music: Aesthetic Dimensions of Law and Justice, University of California Press, 2000, p. 86.

- Lord & Brinkman 2003, p. 75.

- Lord & Brinkman 2003, p. 200.

- Shrock 148

- "Gaude gloriosa Dei Mater (Thomas Tallis) – ChoralWiki". Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- Milsom, John, "Tallis, Thomas", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Thomas 89.

- Willis, 57.

- Lord & Brinkman 2003, p. 86.

- Steinberg, Michael. Choral Masterworks: A Listener’s Guide, New York: Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 291.

- "Tallis's Canon", Hymnary.org.

- Milsom, John, "Sacred Songs in the Chamber" in John Morehen (ed.), English Choral Practice, 1400–1650, CUP, 1995, p. 163.

- Phillips 2005, p. 11.

- Phillips 2005, p. 13.

- Phillips 2005, p. 9.

- Gatens 181.

- "BBC Two - The Tudors, Series 1, Episode 1". BBC. 5 October 2007. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

Sources

- Ackroyd, Peter (2002). Albion: The Origins of the English Imagination. Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-1-85619-721-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cole, S. (2008). "Who is the Father? Changing Perceptions of Tallis and Byrd in Late Nineteenth-Century England". Music and Letters. 89 (2): 212–226. doi:10.1093/ml/gcm082. ISSN 0027-4224. JSTOR 30162967.

- Cole, Suzanne (2008b). Thomas Tallis and His Music in Victorian England. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-380-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Doe, Paul and Allinson, David : Thomas Tallis, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 5 May 2007), (subscription access)

- Farrell, Joseph (2001). Latin Language and Latin Culture: From Ancient to Modern Times. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77663-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gatens. Tallis: Works, all. American Record Guide 68.3 (May–June 2005): 181.

- Holman, Peter (1999). Dowland: Lachrimae (1604). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58829-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lord, Suzanne; Brinkman, David (2003). Music from the Age of Shakespeare: A Cultural History. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-31713-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Manderson, Desmond. Songs Without Music: Aesthetic Dimensions of Law and Justice. University of California Press, 2000.

- Milsom, John. 'Tallis, Thomas' Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (accessed 14 April 2015), (subscription access)

- Milsom, John. "Tallis, Thomas (c.1505–1585)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26954. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Davey, Henry (1898). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 55. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Phillips, Peter (Summer 2005). "Sign of Contradiction: Tallis at 500". Musical Times. 146 (1891): 7–15. JSTOR 30044086.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shrock, Dennis. Choral Repertoire. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Steinberg, Michael. Choral Masterworks: A Listener’s Guide. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- St James's Palace; Rimbault, Edward F. The Old Cheque-Book. Chapel Royal. Westminster: J.B, Nichols and Sons.

- Thomas, Jane Resh (1998). Behind the Mask: The Life of Queen Elizabeth I. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-395-69120-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walker, Ernest (1907). A History of Music in England. Oxford: Clarendon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas Tallis. |

- Thomas Tallis at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- BBC Radio 3 Discovering Music program on Spem in Alium and related works

- Listen to free recordings of Latin church music and English church music from Umeå Akademiska Kör

- The Mutopia Project has compositions by Thomas Tallis

- Free access to high-resolution images of manuscripts containing works by Tallis from Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music

- Free scores by Thomas Tallis in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free scores by Thomas Tallis at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- In Pace in Idipsum, edited by quilisma-publications.info

- Image of Tallis's signature in a book from one of his early places of employment, Waltham Abbey.