New York Botanical Garden

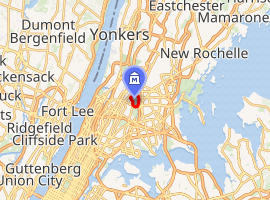

The New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) is a botanical garden located at Bronx Park in the Bronx, New York City. Established in 1891, it is located on a 250-acre (100 ha) site that contains a landscape with over one million living plants; the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory, a greenhouse containing several habitats; and the LuEsther T. Mertz Library, which contains one of the world's largest collections of botany-related texts. As of 2016, over a million people visit the New York Botanical Garden annually.

| |

Visitor Center in June 2012. | |

| |

| Established | 1891 |

|---|---|

| Location | The Bronx, New York City |

| Public transit access | Metro-North Railroad: Botanical Garden New York City Subway: New York City Bus: Bx12, Bx12 SBS, Bx19, Bx22, Bx26 |

| Website | www |

New York Botanical Garden | |

| Location | Southern and Bedford Park Boulevards Bronx, New York 10458 |

| Coordinates | 40°51′49″N 73°52′42″W |

| Area | 250 acres (100 ha) |

| Built | 1891 |

| Architect | Lord & Burnham Co. |

| Architectural style | Victorian era |

| NRHP reference No. | 67000009 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 28, 1967[1] |

| Designated NHL | May 28, 1967 [2] |

NYBG is also a major educational institution, teaching visitors about plant science, ecology, and healthful eating through NYBG's interactive programming. Nearly 90,000 of the annual visitors are children from underserved neighboring communities. An additional 3,000 are teachers from New York City's public school system participating in professional development programs that train them to teach science courses at all grade levels.

NYBG operates one of the world's largest plant research and conservation programs. Since 1967, the garden has been listed as a National Historic Landmark, and several buildings have been designated as official New York City landmarks.

Mission statement

The New York Botanical Garden is an advocate for the plant kingdom. The Garden pursues its mission through its role as a museum of living plant collections arranged in gardens and landscapes across its National Historic Landmark site; through its comprehensive education programs in horticulture and plant science; and through the wide-ranging research programs of the International Plant Science Center.[3]

History

Context

As early as 1877, ideas had been circulating in New York City to create a botanical garden; funding could not be obtained at the time, although the efforts led to parkland being set aside for future use.[4]:47–50 By 1888, the Torrey Botanical Society was promoting the construction of a large botanical garden in New York City. The Garden's creation followed a fund-raising campaign led by the Torrey Botanical Society and Columbia University botanist Nathaniel Lord Britton and his wife Elizabeth Gertrude Britton, who were inspired to emulate the Royal Botanic Gardens in London.[5]:2

In 1889, the Torrey Botanical Society's members decided to build the botanical garden at Bronx Park in the center of the Bronx, New York City's northernmost borough.[5]:2 The Lorillard family owned most of the land at that location.[6] The city had already been given authorization to acquire the land as part of the 1884 New Parks Act, which was intended to preserve lands that would soon become part of New York City.[7]:166[8][9] Some 640 acres (2.6 km2) of land surrounding the Lorillard estate was acquired by the City of New York as part of Bronx Park in 1888–1889.[6]

Establishment

By act of the New York State Legislature, the New York Botanical Garden was established on April 28, 1891.[10]:523 The garden occupied part of the grounds of the Lorillard estate and a parcel that was formerly the easternmost portion of the campus of St. John's College (now Fordham University);[11] the latter included three graves of the Fordham University Cemetery, which were then relocated.[12] The stated purpose of the act was:

... for the purpose of establishing and maintaining a botanical garden and museum and arboretum therein, for the collection of and culture of plants, flowers, shrubs and trees, the advancement of botanical science and knowledge, and the prosecution of original researches therein and in kindred subjects, for affording instruction in the same, for the prosecution and exhibition of ornamental and decorative horticulture and gardening, and for the entertainment, recreation and instruction of the people.[4]:49[5]:2[10]:524

As per the acts of incorporation, a board of directors would manage the NYBG. The board of directors included Columbia College's president and professors of biology, chemistry, and geology; the presidents of the Torrey Society, New York City Board of Education, and the Department of Public Parks' board of commissioners; the Mayor of New York City; and nine other members elected to the board.[5]:2[10]:523–524 The legislation would provide 250 acres (100 ha) within Bronx Park to the NYBG, and enable the board of directors to construct a library and conservatory, if at least $250,000 was raised within five years. If this condition were reached, the city would then issue $0.5 million in bonds.[5]:2[10]:524 The principal officers of the new corporation set up for the garden were Cornelius Vanderbilt, Andrew Carnegie and J.P. Morgan, with Nathaniel Lord Britton as the new secretary.[4]:47–50

Prominent civic leaders and financiers, including Vanderbilt, Carnegie, and Morgan, agreed to match the City's commitment to finance the buildings and improvements.[5]:2 By May 1895, the $250,000 in bonds had been raised[13] but the plans had not been fully confirmed.[14] The Board of Directors then asked landscape architect Calvert Vaux and his partner, Parks Superintendent Samuel Parsons Jr., to consult on site selection. The north end of Bronx Park was decided as the best location for the NYBG.[15] By August 1895, the architects had started a survey on the site. Because the Bronx River and various small tributaries ran through the park, drainage was a major consideration.[16] Though Vaux's preliminary layout was approved in October 1895, he died the following month.[5]:3 The topographical survey was completed in March 1896.[17] The master plan was created by a team that included Britton & Parsons, as well as landscape engineer John R. Brinley, landscape gardener Samuel Henshaw, botanist Lucien Marcus Underwood, and architects Robert W. Gibson and Lincoln Pierson (the latter from the firm Lord & Burnham).[5]:3

The LuEsther T. Mertz Library and Enid A. Haupt Conservatory were among the first structures at the NYBG to open. The Library was built between 1897 and 1900,[5]:4 and the Conservatory was built around the same time, being completed in 1902.[18]

Later operations

For over a century after its opening, the NYBG refused to charge admission.[19] Because of this. as well as insufficient government and private funding, its budget deficit started to increase in the 1950s.[20] After the city cut the NYBG's budget in 1970, the garden was forced to remain closed for 3 to 4 days a week, and officials worried that this could eventually lead to permanent closure.[21] In 1974, for the first time in the botanical garden's history, officials had to annually petition New York State Legislature for funds. That year, the NYBG announced a major renovation to the conservatory and the addition of a building dedicated to displaying plants in different habitats.[20] The next year, budget cuts related to the 1975 New York City fiscal crisis resulted in the NYBG being closed on weekdays for the first time in its history.[22]

In 1988, the NYBG announced a renovation of its museum building, including the addition of a new annex, which was supposed to open in 1991.[23] By the early 1990s, the NYBG facilities were neglected. The garden did not have enough space in its parking lots to accommodate all its visitors, turning away potential guests. Many areas were neglected, except for the 40 acres (16 ha) surrounding the conservatory, and a wetland had even been created unintentionally due to a broken sewer.[24] A controversy arose in 1994 when the adjacent Fordham University proposed building a 480-foot-tall (150 m) radio tower for its radio station WFUV directly across from the Haupt Conservatory.[25] The dispute continued until 2002, after several years of failed resolutions, when Montefiore Medical Center offered to move WFUV's antenna to its own facilities.[26]

By the mid-1990s, additions to the NYBG were being undertaken to reverse years of neglect.[24] In 1994 the formerly free garden started charging an admission fee to fund these improvements as well as the continued maintenance of existing facilities.[19] The Everett Children's Garden opened in mid-1998.[27] By 2000, the NYBG had requested $300 million for renovations, including a new gift shop and renovation of the greenhouses and roads.[28] A new visitor center and gift shop were announced the following year, which would replace temporary facilities built in 1990.[29] The new main entrance, with a gift shop, bookstore, plaza, restrooms, cafe, and information kiosks, was completed in 2004 at a cost of $21 million.[30] Meanwhile, the addition of the library annex was delayed to 1994,[31] then to 2000.[32] Construction on the annex started in 1998[33] and it opened in 2002 as the International Plant Science Center.[34]

In February 2020, NYBG announced that it is partnering with Douglaston Development to create affordable apartments on the northwest edge of the garden. [35]

Grounds

The Garden contains 50 different gardens and plant collections. There is a serene cascade waterfall, as well as wetlands and a 50-acre (20 ha) tract of original, never-logged, old-growth New York forest.[36]

Garden highlights include the 1890s-vintage Haupt Conservatory (designed by Lord & Burnham); the Peggy Rockefeller Rose Garden (originally laid out by Beatrix Jones Farrand in 1916); an alpine rock garden; a Herb Garden (designed by Penelope Hobhouse),[37] and a 37-acre (15 ha) conifer collection. The NYBG's extensive research facilities include a propagation center, 550,000-volume research library,[38] and an herbarium of 7.2 to 7.8 million botanical specimens dating back more than three centuries, among the largest in the world.[39][40]

At the heart of the Garden is the Thain Family Forest,[41] an old-growth forest. It is the largest existing remnant of the original forest which covered all of New York City before the arrival of European settlers in the 17th century. The forest, which was never logged, contains oaks, American beeches, cherry, birch, tulip and white ash trees, some more than two centuries old.[42][43]

The forest itself is split by the Bronx River, the only fresh water river in New York City, and this stretch of the river includes a riverine canyon and rapids.[36] Along the shores sits the Stone Mill, previously known as the Lorillard Snuff Mill, built in 1840.[44] Sculptor Charles Tefft created the Fountain of Life on the grounds in 1905.[5]:9

The Jane Watson Irwin Perennial Garden was designed in the 1970s by Dan Kiley and redefined by horticulturalist Lynden Miller in the 1980's and again in 2003.[45]

Research laboratories

The Pfizer Plant Research Laboratory, built with funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, New York State and New York City, and named for its largest private donor, is a major new research institution at the Garden that opened in 2006. The laboratory is a pure research institution, with projects more diverse than research in universities and pharmaceutical companies.

The laboratory's research emphasis is on plant genomics, the study of how genes function in plant development. One question scientists hope to answer is Darwin's "abominable mystery"; when, where, and why flowering plants emerged. The laboratory's research also furthers the discipline of molecular systematics, the study of DNA as evidence that can reveal the evolutionary history and relationships of plant species. Staff scientists also study plant use in immigrant communities in New York City and the genetic mechanisms by which neurotoxins are produced in some plants, work that may be related to nerve disease in humans.

A staff of 200 trains forty-two doctoral students at a time, from all over the world. Since the 1890s, scientists from the NYBG have mounted about 2,000 exploratory missions worldwide to collect plants in the wild.

At the Pfizer Plant Research Laboratory, genomic DNA from many different species of plants is extracted to create a library of the DNA of the world's plants. This collection is stored in a 768-square-foot (71.3 m2) DNA storage room with 20 freezers housing millions of specimens, including rare, endangered or extinct species. To protect the collection during winter power outages, there is a backup 300-kilowatt electric generator.

The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation has granted the NYBG $572,000 to begin a project called TreeBOL, the Tree Barcode of Life. By sampling the DNA from all 100,000 different species of trees from around the world, TreeBOL will document the diversity of plant life, and advance the process of plant DNA barcoding.[46][47]

LuEsther T. Mertz Library

Founded in 1899 and named after supporter LuEsther Mertz,[38]:33 the LuEsther T. Mertz Library is located in the northern section of NYBG.[36] A 2002 New York Times article mentioned that the library had 775,000 items and 6.5 million plant specimens in its collection.[34] However, a book published in 2014 by the NYBG mentioned that the library had "550,000 physical volumes and 1,800 journal titles".[38]:33 As of 2016 the Mertz Library still contained one of the world's largest collections of botany-related texts. Stephen Sinon, who leads the NYBG's special collections, research and archives, called its collection "the largest of its kind in the world under one roof".[48][49]

The library is housed in what was formerly known as the NYBG's Museum Building or Administration Building. Construction started in 1897[50] and it was completed in 1900.[51] The structure was designed by Robert W. Gibson[52] in the Renaissance Revival style.[5]:1

Enid A. Haupt Conservatory

The Enid A. Haupt Conservatory, named after Enid A. Haupt, is a greenhouse located toward the western end of the NYBG.[36] The conservatory was designed by the major greenhouse company of the late 1890s, Lord and Burnham Co. The design was modeled after the Palm House at the Royal Botanic Garden and Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace in Italian Renaissance style.[53] Groundbreaking took place on January 3, 1899 and construction was completed in 1902 at a cost of $177,000.[53] The building was constructed by John R. Sheehan under contract for the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.[54] Since the original construction, major renovations took place in 1935, 1950, 1978, and 1993.[53]

The Conservatory houses numerous tropical plants and flowers, cacti and other desert plants, and rainforest vegetation. In summer months, the two pools adjacent to the Conservatory display many varieties of lotuses and water lilies.[55]

William & Lynda Steere Herbarium

The William & Lynda Steere Herbarium, in the International Plant Science Center behind the library,[36] is one of the largest herbaria in the world, with approximately 7.2 million[39] to 7.8 million specimens.[40][56] after the French National Museum of Natural History in Paris. Founded in 1891, the herbarium quickly became a repository for many important collections. In 1895 the garden incorporated the herbarium of Columbia College, an acquisition of approximately 600,000 specimens, including the private herbaria of John Torrey and C. F. Meisner. In 1945 the garden incorporated the herbaria of the Columbia College of Pharmacy and Princeton University.[57] The herbarium is named after William Steere (son of William C. Steere) and his wife Lynda, who endowed the herbarium in 2002.[40][58]

Executive leadership

- Dr. Nathaniel Lord Britton (1891–1929)[59]

- Elmer D. Merrill (1930–1935)[60]

- Dr. Marshall A. Howe (1935–1936)[61]

- Dr. Henry A. Gleason (acting, 1937–1938)[62]

- Dr. William J. Robbins (1938–1958)[63]

- Dr. William C. Steere (1958–1972)[64]

- Dr. Howard S. Irwin (1973–1979)[65]

- James M. Hester (1980–1989)[66]

- Gregory Long (1989–2018)[67]

- Dr. Carrie Rebora Barratt (2018–present)

Publications

The NYBG published The Garden Journal (ISSN 0016-4585) from 1977 to 1990 and from 1931 has produced the scientific journal, Brittonia.[68]

Landmark status

The New York Botanical Garden was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1967.[2][69][70] In addition, three structures are designated as individual New York City landmarks: the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory (designated in 1973),[18]:1 the LuEsther T. Mertz Library (2009),[5]:1 and the Lorillard Snuff Mill (1966,[44] also separately on the National Register of Historic Places).[71]

See also

- Education in New York City

- List of herbaria in North America

- List of botanical gardens and arboretums in New York

- List of museums and cultural institutions in New York City

- List of National Historic Landmarks in New York City

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Bronx County, New York

- Other botanical gardens in New York City

- Brooklyn Botanic Garden

- Queens Botanical Garden

- Staten Island Botanical Garden

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- "The New York Botanical Garden". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. September 17, 2007. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013.

- "Mission and History". New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- Tanner, Ogden (1991). The New York Botanical Garden. New York: Walker and Company.

- "Museum Building, Fountain of Life, and Tulip Tree Allee, New York Botanical Garden" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 24, 2009.

- Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0300055366.

- Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300055366.

- "Bronx Park Highlights : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

-

- "The Albany Legislators" (PDF). The New York Times. Albany, New York. March 25, 1884. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- "Proposed New Parks" (PDF). The New York Times. January 24, 1884. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- "An act to provide for the establishment of a botanic garden and arboretum". Laws of the State of New York Passed at the Sessions ... 114th Session: 523–525. 1891 – via HathiTrust.

- Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0300055366.

- "Fordham University History: Fordham Cemetery". Fordham University Libraries. Archived from the original on January 1, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- "BOTANICAL GARDEN PLANS; PROF. BRITTON'S LECTURE BEFORE THE GARDENERS' CLUB. Scenes at Bronx Park as It Now Is -- Views of Other Places Which This Institution Will Rival". The New York Times. May 10, 1896. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- "FOR THE BOTANIC GARDEN; Only $11,000 Needed to Complete the $250,000 Required Fund -- Plans Not Yet Fully Decided On". The New York Times. June 13, 1895. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- "NO BETTER SITE FOUND; The Choice of Bronx Park for a Botanical Garden. ITS MANY SPECIAL ADVANTAGES Chosen After Careful Consideration by Botanists -- N.L. Britton Tells About. Its Selection". The New York Times. August 18, 1895. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- "BOTANIC GARDEN SURVEY; Work in Bronx Park Will Be Begun Within a Short Time. NATURAL BEAUTIES TO BE PRESERVED". The New York Times. August 15, 1895. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- "PLANS FOR THE BOTANICAL GARDEN.; Work to be Begun in the Spring -- 2,500 Trees and Shrubs Are Now Ready for Transplanting". The New York Times. March 8, 1896. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- "The Conservatory, New York Botanical Garden" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 16, 1973.

- Purdy, Matthew (August 2, 1994). "Bronx Garden Imposes Fee For Admission". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Carmody, Deirdre (March 13, 1974). "Bronx Botanical Garden Sprouts Plan To Erect New Building and Fix Old One". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- "Botanical Garden Feels Budget Pinch". The New York Times. December 22, 1970. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Hess, John L. (December 27, 1975). "Cuts Force Closings at Botanical Garden". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Anderson, Susan Heller (February 24, 1988). "Bronx Botanical Garden Plans an Expansion". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Martin, Douglas (December 13, 1995). "Garden Grows in New Direction;Struggling Bronx Institution Aims to Widen Appeal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Dunlap, David W. (July 6, 1994). "A Tower Pits Fordham vs. Botanical Garden". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Elliott, Andrea (May 14, 2004). "Deal Would End 10-Year Feud on Fordham's Radio Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- "TRAVEL ADVISORY; A Children's Garden Grows in the Bronx". The New York Times. April 19, 1998. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Lipton, Eric (October 4, 2000). "Botanical Garden Is Seeking $300 Million". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- "POSTINGS: $9 Million Project at New York Botanical Garden Designed by Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates; Amid the Flowers, a Visitor Center". The New York Times. February 4, 2001. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Collins, Glenn (April 24, 2004). "Seeing the Garden From the Trees; For Its New Visitor Center, Botanical Landmark Preserves the Landscaping". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- "The Botanical Garden sows $32M project". New York Daily News. October 7, 1992. p. 33. Retrieved November 5, 2019 – via newspapers.com

- "POSTINGS: New for New York Botanical Garden; Ivy-Walled Herbarium". The New York Times. November 2, 1997. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- "Cornerstone unveiled for Bronx botany study center". Democrat and Chronicle. September 29, 1998. p. 1. Retrieved November 5, 2019 – via newspapers.com

- Collins, Glenn (April 15, 2002). "Beyond Flowers, a Grove of Academe; Refurbished Botanical Garden Looks to Raise Scholarly Profile". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Spivack, Caroline (February 12, 2020). "New York Botanical Garden plans Bronx affordable housing project". Curbed NY. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- "Interactive Map » New York Botanical Garden". New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Donald, Caroline (March 30, 2008). "Gardening guru Penelope Hobhouse sells her Dorset house and garden". The Sunday Times. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- New York Botanical Garden; Fraser, S.M.; Sellers, V.B. (2014). Flora Illustrata: Great Works from the LuEsther T. Mertz Library of the New York Botanical Garden. New York Botanical Garden. ISBN 978-0-300-19662-7. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- "The William and Lynda Steere Herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden, Global Plants on JSTOR". plants.jstor.org. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- "The William and Lynda Steere Herbarium". www.nybg.org. January 24, 2019.

- "Forest » New York Botanical Garden". New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- Rothstein, Edward (November 3, 2011). "Where the Lenape Trod". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "20 facts you definitely didn't know about the New York Botanical Garden". Time Out New York. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "Lorillard Snuff Mill, New York Botanical Garden" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. April 19, 1966. p. 1. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Edeiken, Louise. "Jane Watson Irwin Perennial Garden". New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- "Tree-BOL to Barcode World's 100,000 Trees". www.bgci.org. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2008.

- "AP article".

- Blakemore, Erin. "Go Inside New York's Nearly Secret Botanical Library". Smithsonian. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Brooks, Katherine (July 5, 2016). "Welcome To The Library Hiding In A Garden Hiding In New York City". HuffPost. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- "New York Botanical Garden". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 11, 1897. p. 12. Retrieved November 6, 2019 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com

- "Harlem and the Bronx". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. March 27, 1900. p. 15. Retrieved November 6, 2019 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com

- "FOR THE STUDY OF BOTANY; A QUARTER OF A MILLION DOL- LARS FOR A BUILDING. Plans of the New-York Botanical Gar- den Association for the Best In- stitution of Its Kind in the Country". The New York Times. November 28, 1896. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- Linda Koebner, "Green house," Landscape Architecture. 87.5 1997, p. 62.

- Tanner, Ogden. "The New York Botanical Garden", New York. Walker and Company, 1991, p. 90.

- "Conservatory » New York Botanical Garden".

- "Index Herbariorum - The William & Lynda Steere Herbarium". sweetgum.nybg.org. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Holmgren, P. K., J. A. Kallunki & B. M. Thiers. 1996. "A short description of the collections of The New York Botanical Garden Herbarium (NY)." Brittonia. 48(3): 285-296.

- "William and Lynda Steere".

- "Nathaniel Lord Britton records (RG4)". New York Botanical Garden. 2006. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- "Elmer Drew Merill records (RG4)". New York Botanical Garden. 2006. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- Stafler, Frans Antonie; Cowan, Richard S. (1976). "Howe, Marshall Avery". Taxonomic literature: a selective guide to botanical publications and collections with dates, commentaries and types. I (2nd ed.). Utrecht: Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema. pp. 347–48. ISBN 9789031302246. OCLC 2709682.

- "Henry A. Gleason records (RG4)". New York Botanical Garden. 2006. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- Kavanagh, Frederick; Hervey, Annette (1991). "William Jacob Robbins 1890-1978" (PDF). Biographical Memoirs. 60. Washington D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. pp. 301–306.

- Crum, Howard (1977). "William Campbell Steere: an account of his life and work". The Bryologist. 80 (4): 662–694. doi:10.2307/3242430. JSTOR 3242430.

- "Howard S. Irwin records (RG4)". New York Botanical Garden. 2006. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- "James Hester, 90, Dies; Guided N.Y.U. to Become a Major University". The New York Times. January 3, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- Kahn, Eve M. (April 20, 2017). "A Farewell to Flowers: Botanical Garden's Leader Steps Down". The New York Times. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- "Brittonia". Springer Nature. 2020. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ""New York Botanical Garden", January 22, 1976, by Richard Greenwood: National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination". National Park Service. January 22, 1976.

- "New York Botanical Garden--Accompanying 17 photos, from c.1962". National Park Service. January 22, 1976.

- "Lorillard Snuff Mill". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. September 15, 2007. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011.

External links

| Wikidata has the property: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New York Botanical Garden. |

- Official website

- "New York Botanical Garden collected news and commentary". The New York Times.

- Brittonia at HathiTrust Digital Library

- Brittonia at SCImago Journal Rank

- Brittonia at Botanical Scientific Journals