Sweet potato

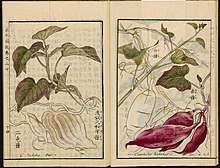

The sweet potato or sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas) is a dicotyledonous plant that belongs to the bindweed or morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its large, starchy, sweet-tasting, tuberous roots are a root vegetable.[1][2] The young leaves and shoots are sometimes eaten as greens. The sweet potato is commonly thought to be a type of potato (Solanum tuberosum) but does not belong to the nightshade family, Solanaceae, but both families belong to the same taxonomic order, the Solanales. The sweet potato, especially the orange variety, is often called a "yam" in parts of North America, but is botanically very distinct from true yams.

| Sweet potato | |

|---|---|

| Sweet potato tubers | |

_Flower.jpg) | |

| Sweet potato flower in Hong Kong | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Convolvulaceae |

| Genus: | Ipomoea |

| Species: | I. batatas |

| Binomial name | |

| Ipomoea batatas | |

The plant is a herbaceous perennial vine, bearing alternate heart-shaped or palmately lobed leaves and medium-sized sympetalous flowers. The edible tuberous root is long and tapered, with a smooth skin whose color ranges between yellow, orange, red, brown, purple, and beige. Its flesh ranges from beige through white, red, pink, violet, yellow, orange, and purple. Sweet potato cultivars with white or pale yellow flesh are less sweet and moist than those with red, pink or orange flesh.[3]

Ipomoea batatas is native to the tropical regions in the Americas.[4][5] Of the approximately 50 genera and more than 1,000 species of Convolvulaceae, I. batatas is the only crop plant of major importance—some others are used locally (e.g., I. aquatica "kangkong"), but many are poisonous. The genus Ipomoea that contains the sweet potato also includes several garden flowers called morning glories, though that term is not usually extended to Ipomoea batatas. Some cultivars of Ipomoea batatas are grown as ornamental plants under the name tuberous morning glory, used in a horticultural context.

Naming

Although the soft, orange sweet potato is often called a "yam" in parts of North America, the sweet potato is very distinct from the botanical yam (Dioscorea), which has a cosmopolitan distribution,[6] and belongs to the monocot family Dioscoreaceae. A different crop plant, the oca (Oxalis tuberosa, a species of wood sorrel), is called a "yam" in many parts of Polynesia, including New Zealand.

Although the sweet potato is not closely related botanically to the common potato, they have a shared etymology. The first Europeans to taste sweet potatoes were members of Christopher Columbus's expedition in 1492. Later explorers found many cultivars under an assortment of local names, but the name which stayed was the indigenous Taino name of batata. The Spanish combined this with the Quechua word for potato, papa, to create the word patata for the common potato.

Some organizations and researchers advocate for the styling of the name as one word—sweetpotato—instead of two, to emphasize the plant's genetic uniqueness from both common potatoes and yams and to avoid confusion of it being classified as a type of common potato.[7][8][9] In its current usage in American English, the styling of the name as two words is still preferred.[10]

In Argentina, Venezuela, Puerto Rico, Brazil and the Dominican Republic the sweet potato is called batata. In Mexico, Peru, Chile, Central America, and the Philippines, the sweet potato is known as camote (alternatively spelled kamote in the Philippines), derived from the Nahuatl word camotli.[11]

In Peru, the Quechua name for a type of sweet potato is kumar, strikingly similar to the Polynesian name kumara and its regional Oceanic cognates (kumala, umala, 'uala, etc.), which has led some scholars to suspect an instance of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact. This theory is also supported by genetic evidence.[12]

In Australia, about 90% of production is devoted to the orange cultivar named "Beauregard", which was originally developed by the Louisiana Agricultural Experiment Station in 1981.[13]

In New Zealand, the original Māori varieties bore elongated tubers with white skin and a whitish flesh[14] (which, it is thought, points to pre-European cross-Pacific travel).[15] Known as kumara (now spelled kūmara in the Māori language), the most common cultivar now is the red cultivar called Owairaka, but orange ("Beauregard"), gold, purple and other cultivars are also available.[16][17] Kumara is particularly popular as a roasted food, often served with sour cream and sweet chili sauce.

Origin

The origin and domestication of sweet potato occurred in either Central or South America.[18] In Central America, domesticated sweet potatoes were present at least 5,000 years ago,[19] with the origin of I. batatas possibly between the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico and the mouth of the Orinoco River in Venezuela.[20] The cultigen was most likely spread by local people to the Caribbean and South America by 2500 BCE.[21]

The sweet potato was grown in Polynesia before western exploration as the Ipomoea batatas, which is generally spread by vine cuttings rather than by seeds.[22] Sweet potato has been radiocarbon-dated in the Cook Islands to 1210-1400 CE.[14] A common hypothesis is that a vine cutting was brought to central Polynesia by Polynesians who had traveled to South America and back, and spread from there across Polynesia to Easter Island, Hawaii and New Zealand.[14][23][24] Genetic traces of the Zenú, a people inhabiting the Pacific coast of present-day Colombia, indicate possible transport of the sweet potato to Polynesia prior to European contact.[25]

Divergence time estimates suggest that sweet potatoes might have been present in Polynesia thousands of years before humans arrived there,[26][27] although other reports dispute this.[14][28]

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 359 kJ (86 kcal) |

20.1 g | |

| Starch | 12.7 g |

| Sugars | 4.2 g |

| Dietary fiber | 3 g |

0.1 g | |

1.6 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 89% 709 μg79% 8509 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 7% 0.078 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 5% 0.061 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 4% 0.557 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 16% 0.8 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 16% 0.209 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 3% 11 μg |

| Vitamin C | 3% 2.4 mg |

| Vitamin E | 2% 0.26 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 3% 30 mg |

| Iron | 5% 0.61 mg |

| Magnesium | 7% 25 mg |

| Manganese | 12% 0.258 mg |

| Phosphorus | 7% 47 mg |

| Potassium | 7% 337 mg |

| Sodium | 4% 55 mg |

| Zinc | 3% 0.3 mg |

"Sweet potato". USDA Database. | |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Dispersal in historical times

Sweet potatoes were first introduced to the Philippines during the Spanish colonial period (1521-1598) via the Manila galleons, along with other New World crops.[29] It was introduced to the Fujian province of China in about 1594 from Luzon, in response to a major crop failure. The growing of sweet potatoes was encouraged by the Governor Chin Hsüeh-tseng (Jin Xuezeng).[30]

Sweet potatoes were also introduced to the Ryukyu Kingdom, present-day Okinawa, Japan, in the early 1600s by the Portuguese.[31][32][33] Sweet potatoes became a staple in Japan because they were important in preventing famine when rice harvests were poor.[33][34] Sweet potatoes were later planted in Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshimune's private garden.[35] It was also introduced to Korea in 1764.[36]

The sweet potato arrived in Europe with the Columbian exchange. It is recorded, for example, in Elinor Fettiplace's Receipt Book, compiled in England in 1604.[37][38]

Transgenicity

The genome of cultivated sweet potatoes contains sequences of DNA from Agrobacterium, with genes actively expressed by the plants.[39] Transgenes were observed both in closely related wild relatives of the sweet potato, and in more distantly related wild species.[39] Studies indicated that the sweet potato genome evolved over millennia, with eventual domestication of the crop taking advantage of natural genetic modifications.[39] These observations make sweet potatoes the first known example of a naturally transgenic food crop.[39][40]

Cultivation

The plant does not tolerate frost. It grows best at an average temperature of 24 °C (75 °F), abundant sunshine and warm nights. Annual rainfalls of 750–1,000 mm (30–39 in) are considered most suitable, with a minimum of 500 mm (20 in) in the growing season. The crop is sensitive to drought at the tuber initiation stage 50–60 days after planting, and it is not tolerant to water-logging, as it may cause tuber rots and reduce growth of storage roots if aeration is poor.[41]

Depending on the cultivar and conditions, tuberous roots mature in two to nine months. With care, early-maturing cultivars can be grown as an annual summer crop in temperate areas, such as the Eastern United States and China. Sweet potatoes rarely flower when the daylight is longer than 11 hours, as is normal outside of the tropics. They are mostly propagated by stem or root cuttings or by adventitious shoots called "slips" that grow out from the tuberous roots during storage. True seeds are used for breeding only.

They grow well in many farming conditions and have few natural enemies; pesticides are rarely needed. Sweet potatoes are grown on a variety of soils, but well-drained, light- and medium-textured soils with a pH range of 4.5–7.0 are more favorable for the plant.[2] They can be grown in poor soils with little fertilizer. However, sweet potatoes are very sensitive to aluminum toxicity and will die about six weeks after planting if lime is not applied at planting in this type of soil.[2] Because they are sown by vine cuttings rather than seeds, sweet potatoes are relatively easy to plant. Because the rapidly growing vines shade out weeds, little weeding is needed. A commonly used herbicide to rid the soil of any unwelcome plants that may interfere with growth is DCPA, also known as Dacthal. In the tropics, the crop can be maintained in the ground and harvested as needed for market or home consumption. In temperate regions, sweet potatoes are most often grown on larger farms and are harvested before first frosts.

Sweet potatoes are cultivated throughout tropical and warm temperate regions wherever there is sufficient water to support their growth.[42] Sweet potatoes became common as a food crop in the islands of the Pacific Ocean, South India, Uganda and other African countries.

A cultivar of the sweet potato called the boniato is grown in the Caribbean; its flesh is cream-colored, unlike the more common orange hue seen in other cultivars. Boniatos are not as sweet and moist as other sweet potatoes, but their consistency and delicate flavor are different than the common orange-colored sweet potato.

Sweet potatoes have been a part of the diet in the United States for most of its history, especially in the Southeast. The average per capita consumption of sweet potatoes in the United States is only about 1.5–2 kg (3.3–4.4 lb) per year, down from 13 kg (29 lb) in 1920. “Orange sweet potatoes (the most common type encountered in the US) received higher appearance liking scores compared with yellow or purple cultivars.”[43] Purple and yellow sweet potatoes were not as well liked by consumers compared to orange sweet potatoes “possibly because of the familiarity of orange color that is associated with sweet potatoes.”[43]

In the Southeastern United States, sweet potatoes are traditionally cured to improve storage, flavor, and nutrition, and to allow wounds on the periderm of the harvested root to heal.[44] Proper curing requires drying the freshly dug roots on the ground for two to three hours, then storage at 29–32 °C (85–90 °F) with 90 to 95% relative humidity from five to fourteen days. Cured sweet potatoes can keep for thirteen months when stored at 13–15 °C (55–59 °F) with >90% relative humidity. Colder temperatures injure the roots.[45][46]

| Sweet potato production – 2017 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Production (millions of tonnes) |

Diseases

Production

In 2017, global production of sweet potatoes was 113 million tonnes, led by China with 64% of the world total (table). Secondary producers were Malawi and Nigeria.[47]

Nutrient content

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 378 kJ (90 kcal) |

20.7 g | |

| Starch | 7.05 g |

| Sugars | 6.5 g |

| Dietary fiber | 3.3 g |

0.15 g | |

2.0 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 120% 961 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 10% 0.11 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 9% 0.11 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 10% 1.5 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 22% 0.29 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 2% 6 μg |

| Vitamin C | 24% 19.6 mg |

| Vitamin E | 5% 0.71 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 4% 38 mg |

| Iron | 5% 0.69 mg |

| Magnesium | 8% 27 mg |

| Manganese | 24% 0.5 mg |

| Phosphorus | 8% 54 mg |

| Potassium | 10% 475 mg |

| Sodium | 2% 36 mg |

| Zinc | 3% 0.32 mg |

"Sweet potato". USDA Database. | |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Besides simple starches, raw sweet potatoes are rich in complex carbohydrates, dietary fiber and beta-carotene (a provitamin A carotenoid), with moderate contents of other micronutrients, including vitamin B5, vitamin B6 and manganese (table).[48] When cooked by baking, small variable changes in micronutrient density occur to include a higher content of vitamin C at 24% of the Daily Value per 100 g serving (right table).[49][50]

The Center for Science in the Public Interest ranked the nutritional value of sweet potatoes as highest among several other foods.[51] In addition, their leaves are edible and can be prepared like spinach or turnip greens.[52]

Sweet potato cultivars with dark orange flesh have more beta-carotene than those with light-colored flesh, and their increased cultivation is being encouraged in Africa where vitamin A deficiency is a serious health problem. A 2012 study of 10,000 households in Uganda found that children eating beta-carotene enriched sweet potatoes suffered less vitamin A deficiency than those not consuming as much beta-carotene.[53]

Comparison to other food staples

The table below presents the relative performance of sweet potato (in column [G]) to other staple foods. While sweet potato provides less edible energy and protein per unit weight than cereals, it has higher nutrient density than cereals.[54]

According to a study by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, sweet potatoes are the most efficient staple food to grow in terms of farmland, yielding approximately 70,000 kcal/ha d.[55]

| Nutrient | Maize (corn)[A] | Rice, white[B] | Wheat[C] | Potatoes[D] | Cassava[E] | Soybeans, green[F] | Sweet potatoes[G] | Yams[Y] | Sorghum[H] | Plantain[Z] | RDA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water (g) | 10 | 12 | 13 | 79 | 60 | 68 | 77 | 70 | 9 | 65 | 3,000 |

| Energy (kJ) | 1,528 | 1,528 | 1,369 | 322 | 670 | 615 | 360 | 494 | 1,419 | 511 | 8,368–10,460 |

| Protein (g) | 9.4 | 7.1 | 12.6 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 13.0 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 11.3 | 1.3 | 50 |

| Fat (g) | 4.74 | 0.66 | 1.54 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 6.8 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 3.3 | 0.37 | 44–77 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 74 | 80 | 71 | 17 | 38 | 11 | 20 | 28 | 75 | 32 | 130 |

| Fiber (g) | 7.3 | 1.3 | 12.2 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 4.2 | 3 | 4.1 | 6.3 | 2.3 | 30 |

| Sugar (g) | 0.64 | 0.12 | 0.41 | 0.78 | 1.7 | 0 | 4.18 | 0.5 | 0 | 15 | minimal |

| Minerals | [A] | [B] | [C] | [D] | [E] | [F] | [G] | [Y] | [H] | [Z] | RDA |

| Calcium (mg) | 7 | 28 | 29 | 12 | 16 | 197 | 30 | 17 | 28 | 3 | 1,000 |

| Iron (mg) | 2.71 | 0.8 | 3.19 | 0.78 | 0.27 | 3.55 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 4.4 | 0.6 | 8 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 127 | 25 | 126 | 23 | 21 | 65 | 25 | 21 | 0 | 37 | 400 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 210 | 115 | 288 | 57 | 27 | 194 | 47 | 55 | 287 | 34 | 700 |

| Potassium (mg) | 287 | 115 | 363 | 421 | 271 | 620 | 337 | 816 | 350 | 499 | 4,700 |

| Sodium (mg) | 35 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 14 | 15 | 55 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 1,500 |

| Zinc (mg) | 2.21 | 1.09 | 2.65 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.99 | 0.3 | 0.24 | 0 | 0.14 | 11 |

| Copper (mg) | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.18 | - | 0.08 | 0.9 |

| Manganese (mg) | 0.49 | 1.09 | 3.99 | 0.15 | 0.38 | 0.55 | 0.26 | 0.40 | - | - | 2.3 |

| Selenium (μg) | 15.5 | 15.1 | 70.7 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0 | 1.5 | 55 |

| Vitamins | [A] | [B] | [C] | [D] | [E] | [F] | [G] | [Y] | [H] | [Z] | RDA |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19.7 | 20.6 | 29 | 2.4 | 17.1 | 0 | 18.4 | 90 |

| Thiamin (B1) (mg) | 0.39 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 1.2 |

| Riboflavin (B2) (mg) | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 1.3 |

| Niacin (B3) (mg) | 3.63 | 1.6 | 5.46 | 1.05 | 0.85 | 1.65 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 2.93 | 0.69 | 16 |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) (mg) | 0.42 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.80 | 0.31 | - | 0.26 | 5 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.62 | 0.16 | 0.3 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.29 | - | 0.30 | 1.3 |

| Folate Total (B9) (μg) | 19 | 8 | 38 | 16 | 27 | 165 | 11 | 23 | 0 | 22 | 400 |

| Vitamin A (IU) | 214 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 13 | 180 | 14,187 | 138 | 0 | 1,127 | 5,000 |

| Vitamin E, alpha-tocopherol (mg) | 0.49 | 0.11 | 1.01 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0 | 0.26 | 0.39 | 0 | 0.14 | 15 |

| Vitamin K1 (μg) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.7 | 120 |

| Beta-carotene (μg) | 97 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 8,509 | 83 | 0 | 457 | 10,500 |

| Lutein+zeaxanthin (μg) | 1,355 | 0 | 220 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 6,000 |

| Fats | [A] | [B] | [C] | [D] | [E] | [F] | [G] | [Y] | [H] | [Z] | RDA |

| Saturated fatty acids (g) | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.14 | minimal |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids (g) | 1.25 | 0.21 | 0.2 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 1.28 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.03 | 22–55 |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids (g) | 2.16 | 0.18 | 0.63 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 3.20 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 1.37 | 0.07 | 13–19 |

| [A] | [B] | [C] | [D] | [E] | [F] | [G] | [Y] | [H] | [Z] | RDA |

Culinary uses

Although the leaves and shoots are also edible, the starchy tuberous roots are by far the most important product. In some tropical areas, they are a staple food crop.

Africa

Amukeke (sun-dried slices of root) and inginyo (sun-dried crushed root) are a staple food for people in northeastern Uganda.[57] Amukeke is mainly served for breakfast, eaten with peanut sauce. Inginyo is mixed with cassava flour and tamarind to make atapa. People eat atapa with smoked fish cooked in peanut sauce or with dried cowpea leaves cooked in peanut sauce. Emukaru (earth-baked root) is eaten as a snack anytime and is mostly served with tea or with peanut sauce. Similar uses are also found in South Sudan.

The young leaves and vine tips of sweet potato leaves are widely consumed as a vegetable in West African countries (Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, for example), as well as in northeastern Uganda, East Africa.[57] According to FAO leaflet No. 13 - 1990, sweet potato leaves and shoots are a good source of vitamins A, C, and B2 (riboflavin), and according to research done by A. Khachatryan, are an excellent source of lutein.

In Kenya, Rhoda Nungo of the home economics department of the Ministry of Agriculture has written a guide to using sweet potatoes in modern recipes.[58] This includes uses both in the mashed form and as flour from the dried tubers to replace part of the wheat flour and sugar in baked products such as cakes, chapatis, mandazis, bread, buns and cookies. A nutritious juice drink is made from the orange-fleshed cultivars, and deep-fried snacks are also included.

In Egypt, sweet potato tubers are known as "batata" (بطاطا) and are a common street food in winter, when street vendors with carts fitted with ovens sell them to people passing time by the Nile or the sea.[59] The cultivars used are an orange-fleshed one as well as a white/cream-fleshed one. They are also baked at home as a snack or dessert, drenched with honey.

In Ethiopia, the commonly found cultivars are black-skinned, cream-fleshed and called "bitatis" or "mitatis". They are cultivated in the eastern and southern lower highlands and harvested during the rainy season (June/July). In recent years, better yielding orange-fleshed cultivars were released for cultivation by Haramaya University as a less sugary sweet potato with higher vitamin A content.[60] Sweet potatoes are widely eaten boiled as a favored snack.

Asia

_2.jpg)

_2.jpg)

In East Asia, roasted sweet potatoes are popular street food. In China, sweet potatoes, typically yellow cultivars, are baked in a large iron drum and sold as street food during winter. In Korea, sweet potatoes, known as goguma, are roasted in a drum can, baked in foil or on an open fire, typically during winter. In Japan, a dish similar to the Korean preparation is called yaki-imo (roasted sweet potato), which typically uses either the yellow-fleshed "Japanese sweet potato" or the purple-fleshed "Okinawan sweet potato", which is known as beni-imo.

Sweet potato soup, served during winter, consists of boiling sweet potato in water with rock sugar and ginger. Sweet potato greens are a common side dish in Taiwanese cuisine, often boiled or sautéed and served with a garlic and soy sauce mixture, or simply salted before serving. They, as well as dishes featuring the sweet potato root, are commonly found at bento (Pe̍h-ōe-jī: piān-tong) restaurants. In northeastern Chinese cuisine, sweet potatoes are often cut into chunks and fried, before being drenched into a pan of boiling syrup.[61]

In some regions of India, sweet potato is roasted slow over kitchen coals at night and eaten with some dressing while the easier way in the south is simply boiling or pressure cooking before peeling, cubing and seasoning for a vegetable dish as part of the meal. In Indian state of Tamil Nadu, it is known as 'Sakkara valli Kilangu'. It is boiled and consumed as evening snack. In some parts of India, fresh sweet potato is chipped, dried and then ground into flour; this is then mixed with wheat flour and baked into chapattis (bread). Between 15 and 20 percent of sweet potato harvest is converted by some Indian communities into pickles and snack chips. A part of the tuber harvest is used in India as cattle fodder.[3]

In Pakistan, sweet potato is known as shakarqandi and is cooked as vegetable dish and also with meat dishes (chicken, mutton or beef). The ash roasted sweet potatoes are sold as a snack and street food in Pakistani bazaars especially during the winter months.[62]

In Sri Lanka, it is called 'Bathala' and tubers are used mainly for breakfast (boiled sweet potato commonly with sambal or grated coconut) or as an supplementary curry dish for rice. There are many other culinary uses with sweet potato as well.

The tubers of this plant, known as kattala in Dhivehi, have been used in the traditional diet of the Maldives. The leaves were finely chopped and used in dishes such as mas huni.[63]

In Japan, both sweet potatoes (called "satsuma-imo") and true purple yams (called "daijo" or "beni-imo") are grown. Boiling, roasting and steaming are the most common cooking methods. Also, the use in vegetable tempura is common. Daigaku-imo is a baked sweet potato dessert. Because it is sweet and starchy, it is used in imo-kinton and some other traditional sweets, such as ofukuimo. Shōchū, a Japanese spirit normally made from the fermentation of rice, can also be made from sweet potato, in which case it is called imo-jōchū. Imo-gohan, sweet potato cooked with rice, is popular in Guangdong, Taiwan and Japan. It is also served in nimono or nitsuke, boiled and typically flavored with soy sauce, mirin and dashi.

In Korean cuisine, sweet potato starch is used to produce dangmyeon (cellophane noodles). Sweet potatoes are also boiled, steamed, or roasted, and young stems are eaten as namul. Pizza restaurants such as Pizza Hut and Domino's in Korea are using sweet potatoes as a popular topping. Sweet potatoes are also used in the distillation of a variety of Soju. A popular Korean side dish or snack, goguma-mattang, also known as Korean candied sweet potato, is made by deep frying sweet potatoes that were cut into big chunks and coating them with caramelized sugar.

In Malaysia and Singapore, sweet potato is often cut into small cubes and cooked with taro and coconut milk (santan) to make a sweet dessert called bubur caca or "bubur cha cha". A favorite way of cooking sweet potato is deep frying slices of sweet potato in batter, and served as a tea-time snack. In homes, sweet potatoes are usually boiled. The leaves of sweet potatoes are usually stir-fried with only garlic or with sambal belacan and dried shrimp by Malaysians.

.jpg)

In the Philippines, sweet potatoes (locally known as camote or kamote) are an important food crop in rural areas. They are often a staple among impoverished families in provinces, as they are easier to cultivate and cost less than rice.[64] The tubers are boiled or baked in coals and may be dipped in sugar or syrup. Young leaves and shoots (locally known as talbos ng kamote or camote tops) are eaten fresh in salads with shrimp paste (bagoong alamang) or fish sauce. They can be cooked in vinegar and soy sauce and served with fried fish (a dish known as adobong talbos ng kamote), or with recipes such as sinigang.[64] The stew obtained from boiling camote tops is purple-colored, and is often mixed with lemon as juice. Sweet potatoes are also sold as street food in suburban and rural areas. Fried sweet potatoes coated with caramelized sugar and served in skewers (camote cue) are popular afternoon snacks.[65] Sweet potatoes are also used in a variant of halo-halo called ginatan, where they are cooked in coconut milk and sugar and mixed with a variety of rootcrops, sago, jackfruit, and bilu-bilo (glutinous rice balls).[66] Bread made from sweet potato flour is also gaining popularity. Sweet potato is relatively easy to propagate, and in rural areas that can be seen abundantly at canals and dikes. The uncultivated plant is usually fed to pigs.

In Indonesia, sweet potatoes are locally known as ubi jalar (lit: spreading tuber) and are frequently fried with batter and served as snacks with spicy condiments, along with other kinds of fritters such as fried bananas, tempeh, tahu, breadfruits, or cassava. In the mountainous regions of West Papua, sweet potatoes are the staple food among the natives there. Using the bakar batu way of cooking (free translation: burning rocks), rocks that have been burned in a nearby bonfire are thrown into a pit lined with leaves. Layers of sweet potatoes, an assortment of vegetables, and pork are piled on top of the rocks. The top of the pile then is insulated with more leaves, creating a pressure of heat and steam inside which cooks all food within the pile after several hours.

In Vietnamese cuisine sweet potatoes are known as khoai lang and they are commonly cooked with a sweetener such as corn syrup, honey, sugar, or molasses.[67]

Young sweet potato leaves are also used as baby food particularly in Southeast Asia and East Asia.[68][69] Mashed sweet potato tubers are used similarly throughout the world.[70]

United States

Candied sweet potatoes are a side dish consisting mainly of sweet potatoes prepared with brown sugar, marshmallows, maple syrup, molasses, orange juice, marron glacé, or other sweet ingredients. It is often served in the US on Thanksgiving. Sweet potato casserole is a side dish of mashed sweet potatoes in a casserole dish, topped with a brown sugar and pecan topping.[71]

The sweet potato became a favorite food item of the French and Spanish settlers and thus continued a long history of cultivation in Louisiana.[72] Sweet potatoes are recognized as the state vegetable of North Carolina.[73] Sweet potato pie is also a traditional favorite dish in Southern U.S. cuisine. Another variation on the typical sweet potato pie is the Okinawan sweet potato haupia pie, which is made with purple sweet potatoes, native to the island of Hawaii and believed to have been originally cultivated as early as 500 CE.[74]

The fried sweet potatoes tradition dates to the early nineteenth century in the United States.[75] Sweet potato fries or chips are a common preparation, and are made by julienning and deep frying sweet potatoes, in the fashion of French fried potatoes. Roasting sliced or chopped sweet potatoes lightly coated in animal or vegetable oil at high heat became common in the United States at the start of the 21st century, a dish called “sweet potato fries”. Sweet potato mash is served as a side dish, often at Thanksgiving dinner or with barbecue.

John Buttencourt Avila is called the "father of the sweet potato industry" in North America.

New Zealand

Before European contact, the Māori grew several varieties of small, yellow-skin, finger-sized kumara (with names including taputini,[76] taroamahoe, pehu, hutihuti, and rekamaroa[77]) that they had brought with them from east Polynesia. Modern trials have shown that these smaller varieties were capable of producing well,[78] but when American whalers, sealers and trading vessels introduced larger cultivars in the early 19th century, they quickly predominated.[79][80][81][82]

Māori traditionally cooked the kūmara in a hāngi earth oven. This is still a common practice when there are large gatherings on marae.

In 1947 black rot (Ceratocystis fimbriata) appeared in kumara around Auckland and increased in severity through the 1950s.[83] A disease-free strain was developed by Joe and Fay Gock. They gifted the strain to the nation, later in 2013 earning them the Bledisloe Cup.[84][85]

There are three main cultivars of kumara sold in New Zealand: 'Owairaka Red' ("red"), 'Toka Toka Gold' ("gold"), and 'Beauregard' ("orange"). The country grows around 24,000 tonnes of kumara annually,[86] with nearly all of it (97%) grown in the Northland region.[87] Kumara are widely available throughout New Zealand year-round, where they are a popular alternative to potatoes.[88]

Kumara are an integral part of roast meals in New Zealand. They are served alongside such vegetables as potatoes and pumpkin and, as such, are generally prepared in a savory manner. Kumara are ubiquitous in supermarkets, roast meal takeaway shops and hāngi.

Other

Among the Urapmin people of Papua New Guinea, taro (known in Urap as ima) and the sweet potato (Urap: wan) are the main sources of sustenance, and in fact the word for "food" in Urap is a compound of these two words.[89]

In Spain, sweet potato is called boniato. On the evening of All Souls' Day, in Catalonia (northeastern Spain) it is traditional to serve roasted sweet potato and chestnuts, panellets and sweet wine. The occasion is called La Castanyada.[90] Sweet potato is also appreciated to make cakes or to eat roasted through the whole country.

In Peru, sweet potatoes are called "camote" and are frequently served alongside ceviche. Sweet potato chips are also a commonly sold snack, be it on the street or in packaged foods.

Dulce de batata is a traditional Argentine, Paraguayan and Uruguayan dessert, which is made of sweet potatoes. It is a sweet jelly, which resembles a marmalade because of its color and sweetness but it has a harder texture, and it has to be sliced in thin portions with a knife as if it was a pie. It is commonly served with a portion of the same size of soft cheese on top of it.

In the Veneto (northeast Italy), sweet potato is known as patata mericana in the Venetian language (patata americana in Italian, meaning "American potato"), and it is cultivated above all in the southern area of the region;[91] it is a traditional fall dish, boiled or roasted.

Globally, sweet potatoes are now a staple ingredient of modern sushi cuisine, specifically used in maki rolls. The advent of sweet potato as a sushi ingredient is credited to chef Bun Lai of Miya's Sushi, who first introduced sweet potato rolls in the 1990s as a plant-based alternative to traditional fish-based sushi rolls.[92][93][94]

Non-culinary uses

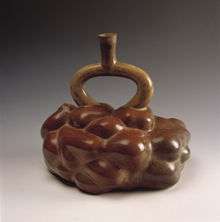

Ceramics modeled after sweet potatoes or camotes are often found in the Moche culture.[95]

In South America, the juice of red sweet potatoes is combined with lime juice to make a dye for cloth. By varying the proportions of the juices, every shade from pink to black can be obtained.[96] Purple sweet potato color is also used as a ‘natural’ food coloring.[97]

Cuttings of sweet potato vine, either edible or ornamental cultivars, will rapidly form roots in water and will grow in it, indefinitely, in good lighting with a steady supply of nutrients. For this reason, sweet potato vine is ideal for use in home aquariums, trailing out of the water with its roots submerged, as its rapid growth is fueled by toxic ammonia and nitrates, a waste product of aquatic life, which it removes from the water. This improves the living conditions for fish, which also find refuge in the extensive root systems.[75][97]

References

- Purseglove, John Williams (1968). Tropical crops: Dicotyledons. Longman Scientific and Technical. New York: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-582-46666-1.

- Woolfe, Jennifer A. (5 March 1992). Sweet Potato: An untapped food resource. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press and the International Potato Center (CIP). ISBN 9780521402958.

- Gad Loebenstein; George Thottappilly (2009). The sweetpotato. pp. 391–425. ISBN 978-1-4020-9475-0.

- "Ipomoea batatas". purdue.edu.

- "Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas) Classification". uwlax.edu.

- "Dioscorea". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- "Sweetpotato: One Word or Two?". International Potato Center. 12 November 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Averre, Charles W.; Wilson, L. George. "Sweetpotato — Why one word?". NCSU Plant Pathology. North Carolina State University Department of Plant Pathology. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Loebenstein, Gad; Thottappilly, George, eds. (2009). The Sweetpotato. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 298. ISBN 9781402094750.

- "What is a Sweetpotato?" (PDF), UC Vegetable Research & Information Center, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California, p. 2, October 2010, retrieved 29 December 2019

- "Nahuatl influences in Tagalog". El Galéon de Acapulco News. Embajada de México, Filipinas. Archived from the original on 27 April 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- Timmer, John (21 January 2013). "Polynesians reached South America, picked up sweet potatoes, went home". Ars Technica. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Dominic and Margaret Jolimont. "Sweet potato". Slater Community Gardens. Retrieved 10 July 2019.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Crowe, Andrew (2018). Pathway of the Birds: The Voyaging Achievements of Māori and their Polynesian Ancestors. Auckland, New Zealand: Bateman. ISBN 9781869539610.

- Field, Michael (23 January 2013). "Kumara origin points to pan-Pacific voyage". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- Yen, D. E. (1963). "The New Zealand Kumara or Sweet Potato". Economic Botany. 17 (1): 31–45. doi:10.1007/bf02985351. JSTOR 4252401.

- "Types of kumara grown in New Zealand". Kaipara Kumara.

- Geneflow 2009. ISBN 9789290438137.

- "Sweet Potato". Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research. Archived from the original on 7 February 2005.

- Austin, Daniel F. (1988). "The taxonomy, evolution and genetic diversity of sweet potatoes and related wild species". In P. Gregory (ed.). Exploration, Maintenance, and Utilization of Sweet Potato Genetic Resources. First Sweet Potato Planning Conference, 1987. Lima, Peru: International Potato Center. pp. 27–60.

- Zhang, D.P.; Ghislain, M.; Huaman, Z.; Cervantes, J.C.; Carey, E.E. (1999). AFLP Assessment of Sweetpotato Genetic Diversity in Four Tropical American Regions (PDF). International Potato Center (CIP) Program report 1997-1998. Lima, Peru: International Potato Center (CIP). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2014.

- "Batatas, Not Potatoes". Botgard.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 19 May 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- van Tilburg, Jo Anne (1994). Easter Island: Archaeology, ecology, and culture. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Bassett, Gordon; et al. "Gardening at the Edge: Documenting the limits of tropical Polynesian kumara horticulture in southern New Zealand" (PDF). New Zealand: University of Canterbury. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011.

- Lizzie Wade (8 July 2020). "Polynesians steering by the stars met Native Americans long before Europeans arrived". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abd7159.

- "Sweet potato history casts doubt on early contact between Polynesia and the Americas". EurekaAlert! Cell Press. 12 April 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- Muñoz-Rodríguez, Pablo; Carruthers, Tom; Wood, John R.I.; Williams, Bethany R.M.; Weitemier, Kevin; Kronmiller, Brent; Ellis, David; Anglin, Noelle L.; Longway, Lucas; Harris, Stephen A.; Rausher, Mark D.; Kelly, Steven; Liston, Aaron; Scotland, Robert W. (2018). "Reconciling conflicting phylogenies in the origin of sweet potato and dispersal to Polynesia". Current Biology. 28 (8): 1246–1256.e12. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.03.020. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 29657119.

- Matisoo-Smith, Lisa. "When did sweet potatoes arrive in the Pacific – Expert Reaction". www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz. Science Media Centre. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Loebenstein, Gad (2009). "Origin, Distribution and Economic Importance". In Loebenstein, Gad; Thottappilly, George (eds.). The Sweetpotato. Springer. ISBN 9781402094743.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1993). Chinese Roundabout: Essays in History and Culture (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 167. ISBN 978-0393309942.

- Goodman, Grant K. (2013). Japan and the Dutch 1600-1853. London: Routledge. pp. 66–67. doi:10.4324/9781315028064. ISBN 9781315028064.

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. (2003). "First Globalization: The Eurasian Exchange, 1500-1800". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 36 (3): 932–933. doi:10.2307/20477565. JSTOR 20477565.

- Obrien, Patricia J. (1972). "The sweet potato: Its origin and dispersal". American Anthropologist. 74 (3): 342–365. doi:10.1525/aa.1972.74.3.02a00070.

- Itoh, Makiko (22 April 2017). "The storied history of the potato in Japanese cooking". The Japan Times. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Takekoshi, Yosaburō (1930). Economic Aspects of the History of the Civilization of Japan. p. 352. ISBN 9780415323802.

- Kim, Jinwung (2012). A History of Korea: From 'Land of the Morning Calm' to states in conflict. p. 255. ISBN 978-0253000781.

- Fettiplace, Elinor (1986) [1604]. Spurling, Hilary (ed.). Elinor Fettiplace's Receipt Book: Elizabethan Country House Cooking. Viking.

- Dickson Wright, 2011. Pages 149–169

- Kyndt, Tina; Quispea, Dora; Zhaic, Hong; Jarretd, Robert; Ghislainb, Marc; Liuc, Qingchang; Gheysena, Godelieve; Kreuzeb, Jan F. (20 April 2015). "The genome of cultivated sweet potato contains Agrobacterium T-DNAs with expressed genes: An example of a naturally transgenic food crop". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (18): 5844–5849. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419685112. PMC 4426443. PMID 25902487.

- "Sweet potato is a natural GMO". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. 22 April 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- Ahn, Peter (1993). Tropical soils and fertilizer use. Intermediate Tropical Agriculture Series. UK: Longman Scientific and Technical Ltd. ISBN 978-0-582-77507-7.

- O'Hair, Stephen K. (1990). "Tropical root and tuber crops". In Janick, J.; Simon, J.E. (eds.). Advances in New Crops. Portland, OR: Timber Press. pp. 424–428. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- Leksrisompong, P.P.; Whitson, M.E.; Truong, V.D.; Drake, M.A. (2012). "Sensory attributes and consumer acceptance of sweet potato cultivars with varying flesh colors". Journal of Sensory Studies. 27 (1): 59–69. doi:10.1111/j.1745-459x.2011.00367.x.

- "Sweet potatoes". North Carolina Sweet Potato Commission (NCSPC).

- "Sweetpotato: Organic Production". National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service.

- "Sweet potato". Produce Facts. UC Davis. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010.

- "Sweet potato production in 2017; World Regions/Production Quantity from pick lists". Statistics Division (FAOSTAT). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- "Sweet potato, raw, unprepared, includes USDA commodity food A230". Nutritiondata.com. Conde Nast. 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- "Sweet potato, cooked, baked in skin, without salt". Nutritiondata.com. Conde Nast. 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- Dincer, C.; Karaoglan, M.; Erden, F.; Tetik, N.; Topuz, A.; Ozdemir, F. (November 2011). "Effects of baking and boiling on the nutritional and antioxidant properties of sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.] cultivars". Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 66 (4): 341–347. doi:10.1007/s11130-011-0262-0. PMID 22101780.

- "10 Worst and Best Foods". Nutrition Action Health Letter. Center for Science in the Public Interest. 2013. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Dyer, Mary H. "Are sweet potato leaves edible?". Gardening Know How. Potato vine plant leaves. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- Coghlan, A. (17 August 2012). "Nutrient-boosted foods protect against blindness". Health. New Scientist. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Scott, Best, Rosegrant, and Bokanga (2000). Roots and tubers in the global food system: A vision statement to the year 2020 (PDF). International Potato Center, and others. ISBN 978-92-9060-203-3.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Roots, tubers, plantains and bananas in human nutrition". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "Nutrient data laboratory". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- Abidin, P.E. (2004). Sweetpotato breeding for northeastern Uganda: Farmer varieties, farmer-participatory selection, and stability of performance (PhD Thesis). The Netherlands: Wageningen University. p. 152 pp. ISBN 90-8504-033-7.

- Nungo, Rhoda A., ed. (1994). Nutritious Kenyan Sweet Potato Recipes. Kakamega, Kenya: Kenya Agricultural Research Institute.

- "The batata man". Egypt Independent. 19 October 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Tsegaw, Tekalign; Dechassa, Nigussie (2008). "Registration of Adu and Barkume: Improved sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) varieties for eastern Ethiopia". East African Journal of Sciences. 2 (2): 189–191. doi:10.4314/eajsci.v2i2.40382.(registration required)

- "CaiPu". ttmeishi.com (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 4 October 2007.

- Aazim, Mohiuddin (17 December 2012). "Exploiting sweet potato potential". InpaperMagazine. Dawn. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- Romero-Frias, Xavier (1999). The Maldive Islanders: A study of the popular culture of an ancient ocean kingdom. Barcelona, ES. ISBN 978-84-7254-801-5.

- "Fusion kamote". The Manila Times (The Sunday Times) Editorials. 16 March 2008. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- Nicole J. Managbanag (25 October 2010). "Elections and banana cue". Sun.Star. sunstar.com.ph/. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- Daluz, Susan G. (2005). "A recipe that supported a brood of 12". Philippine Daily Inquirer. INQ7 Interactive, Inc. an Inquirer and GMA Network Company. Inquirer News Service. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- Bác sĩ Nguyễn Ý Đức. Dinh dưỡng và thực phẩm (in Vietnamese).

- Sweet Potato. South Pacific Commission. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1990. ISSN 1018-0966. Leaflet No. 13.

- Ma, Idelia; Glorioso, G. (January–December 2003). "10 Best Foods for Babies". Food and Nutrition Research Institute. Department of Science and Technology, Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Ember, Carol R.; Ember, Melvin, eds. (2004). "Cultures". Encyclopedia of Medical Anthropology. Springer. p. 596. ISBN 9780306477546.

- Diana Rattray. "Sweet potato casserole recipe with crunchy pecan topping". Southern Food. About.com.

- "History of the Louisiana Yambilee". Yambilee.com.

- "Sweet Potato - North Carolina State Vegetable". State of North Carolina. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- Chung, H.L. (October 1923). "The Sweet Potato in Hawaii" (PDF). ctahr.hawaii.edu. United States Deptartment of Agriculture.

- McLellan Plaisted, S. (October 2011). "Sweet potato fries are not new". hearttoearthcookery.com. Historical Society of York County, Pennsylvania.

- Burtenshaw, M. (2009). "A guide to growing pre-European Māori kumara" (PDF). The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand.

- Tapsell, Enid (1947). "Original Kumara". TJPS. pp. 325–332.

- Wilson, Dee (29 April 2009). "Heritage kumara shows its worth". The Marlborough Express. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Waitangi tribunal and the kumara claim". The Grower. Horticulture New Zealand. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.

- Stokes, Jon (1 February 2007). "Kumara claim becomes hot potato". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "DNA analysis expected to solve kumara row". The New Zealand Herald. NZPA. 8 February 2007. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Kumara". teara.govt.nz.

- Slade, D. A. (1960). "Black rot an important disease of Kumaras". New Zealand Journal of Agriculture. 100 (4).

- Loren, Anna (8 August 2013). "Bledisloe Cup for service to horticulture". Manukau Courier. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "Loading Docs 2016 - How Mr and Mrs Gock Saved the Kumara". Loading Docs. NZ On Screen. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- "Fresh Facts: New Zealand Horticulture" (PDF). Plant & Food Research. 2018. ISSN 1177-2190.

- Barrington, Mike; Downey, Robyn (18 March 2006). "Ohakune has its carrot ... and Dargaville has its kumara". The Northern Advocate. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- "How to cook with kumara". Taranaki Daily News. 3 March 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- Robbins, Joel (1995). "Dispossessing the Spirits: Christian Transformations of Desire and Ecology among the Urapmin of Papua New Guinea". Ethnology. 34 (3): 211–24. doi:10.2307/3773824. JSTOR 3773824.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- es:Castanyada#Castañada

- "la patata americana di Anguillara". Mondo agricolo veneto. Archived from the original on 12 January 2010.

- Knighton, Ryan (6 October 2016). "The Sushi Chef Turning Invasive Species Into Delicacies". Popular Mechanics.

- Kleiner, Matthew (1 February 2019). "Sushi's Role". Yale Daily News. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- Arnott, Christopher (September–October 2016). "New Haven: Sushi celebrity". Yale Alumni Magazine. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- Berrin, Katherine; Larco Museum staff (1997). The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York, NY: Thames and Hudson.

- Verrill, Alpheus Hyatt; Barrett, Otis Warren (1937). Foods America gave the World: The strange, fascinating and often romantic histories of many native American food plants, their origin, and other interesting and curious facts concerning them. Boston, MA: L.C. Page & Co. p. 47.

- "Purple sweet potatoes among "new naturals" for food and beverage colors". September 2013.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Sweet Potato. |

| Look up Sweet potato in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sweet potato. |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

"Sweet Potato". fao.org. 1990. FAO Leaflet 13.