Ipomoea tricolor

Ipomoea tricolor, the Mexican morning glory or just morning glory[1], is a species of flowering plant in the family Convolvulaceae, native to the New World tropics, and widely cultivated and naturalised elsewhere. It is an herbaceous annual or perennial twining liana growing to 2–4 m (7–13 ft) tall. The leaves are spirally arranged, 3–7 cm (1" to 3") long with a 1.5–6 cm (½" to 2") long petiole. The flowers are trumpet-shaped, 4–9 cm (2–4 in) in diameter, most commonly blue with a white to golden yellow centre.

| Ipomoea tricolor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ipomoea tricolor 'Heavenly Blue' | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Convolvulaceae |

| Genus: | Ipomoea |

| Species: | I. tricolor |

| Binomial name | |

| Ipomoea tricolor | |

Cultivation and uses

In cultivation, the species is very commonly grown misnamed as Ipomoea violacea, actually a different though related species. I. tricolor does not tolerate temperatures below 5 °C (41 °F), so in temperate regions it is usually grown as an annual. It is in any case a relatively short-lived plant.

Numerous cultivars of I. tricolor with different flower colours have been selected for use as ornamental plants; widely grown examples include:

- ‘Blue Star’

- ‘Flying Saucers’

- ‘Heavenly Blue’

- ‘Heavenly Blue Improved’

- ‘Pearly Gates’

- ‘Rainbow Flash’

- ‘Skylark’

- ‘Summer Skies’

- ‘Wedding Bells’

The cultivar 'Heavenly Blue' has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[2][3]

Entheogenic use

The seeds, vines, flowers, and leaves contain ergoline alkaloids, and have been used for centuries by many Mexican Native American cultures as an entheogen; R. Gordon Wasson has argued that the hallucinogenic seeds used by the Aztecs under the Nahuatl name tlitliltzin, were the seeds of I. tricolor. Wasson also noted that the modern-day Zapotecs of Oaxaca know the seeds as badoh negro.[4]

Richard Schultes in 1941 described Mexican Native American use in a short report documenting the use dating back to Aztec times cited in TiHKAL by Alexander Shulgin. Further research was published in 1960, when Don Thomes MacDougall reported that the seeds of Ipomoea tricolor were used as sacraments by certain Zapotecs, sometimes in conjunction with the seeds of Rivea corymbosa, another species which has a similar chemical composition, with lysergol instead of ergometrine. This more widespread knowledge has led to a rise in entheogenic use by people other than Native Americans.

The hallucinogenic properties of the seeds are usually attributed to ergine (also known as d-lysergic acid amide, or LSA), although the validity of the attribution remains disputed. Lysergic acid hydroxyethylamide and ergonovine are also considered to be contributing psychedelic alkaloids in the plant. While ergine is listed as a Schedule III substance in the United States, parts of the plant itself are not controlled, and seeds and plants are still sold by many nurseries and garden suppliers.

The seeds also contain glycosides, which may cause nausea if consumed.

Toxic treatments

Commercial seeds are sometimes treated with toxic methylmercury (although the use of methylmercury has been banned in the US and the UK since the 1980s), which serves as a preservative and a cumulative neurotoxic poison that is considered useful by some to discourage recreational use of them. There is no legal requirement in the United States to disclose to buyers that seeds have been treated with a toxic heavy metal compound.[5] According to the book Substances of Abuse, in addition to methylmercury, the seeds are claimed to be sometimes coated with a chemical that cannot be removed with washing that is designed to cause unpleasant physical symptoms such as nausea and abdominal pain. The book states that this chemical is also toxic.[6]

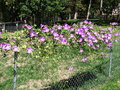

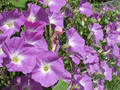

Wedding Bells

Wedding Bells Wedding Bells close-up

Wedding Bells close-up

Colour change

In Ipomoea tricolor 'Heavenly Blue', the colour of the flower changes during blossom according to an increase in vacuolar pH.[7][8][9] This shift, from red to blue, is induced by chemical modifications affecting the anthocyanin molecules present in the petals.

References

- Brickell, Christopher, ed. (2008). The Royal Horticultural Society A-Z Encyclopedia of Garden Plants. United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 570. ISBN 9781405332965.

- "RHS Plant Selector - Ipomoea tricolor". Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 2013-06-14. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- "AGM Plants - Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 53. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Carod-Artal, FJ (2015). "Hallucinogenic drugs in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures". Neurologia. 30 (1): 42–9. doi:10.1016/j.nrl.2011.07.003. PMID 21893367.

- Dunn Chace, Teri (2015). Seeing Seeds: A Journey into the World of Seedheads, Pods, and Fruit. Portland OR: Timber Press. ISBN 978-1604694925.

- Potter, James (2008). Substances of Abuse. Redding CA: Jubilee Enterprises. p. 157. ISBN 978-1930327467.

- Yoshida, Kumi; Kawachi, Miki; Mori, Mihoko; Maeshima, Masayoshi; Kondo, Maki; Nishimura, Mikio; Kondo, Tadao (2005). "The Involvement of Tonoplast Proton Pumps and Na+(K+)/H+ Exchangers in the Change of Petal Color During Flower Opening of Morning Glory, Ipomoea tricolor cv. Heavenly Blue". Plant and Cell Physiology. 46 (3): 407–415. doi:10.1093/pcp/pci057. ISSN 1471-9053. PMID 15695444.

- Yoshida, Kumi; Kondo, Tadao; Okazaki, Yoshiji; Katou, Kiyoshi (1995). "Cause of blue petal colour". Nature. 373 (6512): 291. Bibcode:1995Natur.373..291Y. doi:10.1038/373291a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- Yoshida, Kumi; Miki, Naoko; Momonoi, Kazumi; Kawachi, Miki; Katou, Kiyoshi; Okazaki, Yoshiji; Uozumi, Nobuyuki; Maeshima, Masayoshi; Kondo, Tadao (2009). "Synchrony between flower opening and petal-color change from red to blue in morning glory, Ipomoea tricolor cv. Heavenly Blue". Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B. 85 (6): 187–197. Bibcode:2009PJAB...85..187Y. doi:10.2183/pjab.85.187. ISSN 0386-2208. PMC 3559195. PMID 19521056.