Bicolano people

The Bicolano people (Bikol: Mga Bikolnon) are the fourth-largest Filipino ethnolinguistic group.[2] Their native region is commonly referred to as Bicolandia, which comprises the entirety of the Bicol Peninsula and neighbouring minor islands, all in the southeast portion of Luzon.

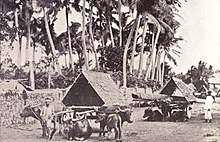

_preparing_Hemp_-Drawing_out_the_fibre_(c._1900%2C_Philippines).jpg) Bicolano men preparing hemp by drawing out its fibers, c. 1900 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 6,299,283[1] (6.84% of the Philippine population) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(Bicol Region, Quezon Province, Northern Samar, Metro Manila) | |

| Languages | |

| Bikol languages Filipino, English (auxiliary) | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (predominantly Roman Catholicism, with minority Protestantism) Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Tagalogs, Visayans (Masbateños and Warays), other Filipinos |

They are largely an agricultural and rural people, producing rice, coconuts, and hemp. Nearly all of them are Christians, predominantly Roman Catholics, but with some Protestant minorities. Their language, which is actually a collection of closely related varieties, is closely related to other languages of the central Philippines, all of which belong to the Austronesian (specifically Malayo-Polynesian) super-family of languages.[3]

History

According to a folk epic entitled Ibalong, the people of the region were formerly called Ibalong or Ibalnong, a name believed to have been derived from Gat Ibal who ruled Sawangan (now the city of Legazpi) in ancient times. Ibalong used to mean the "people of Ibal"; eventually, this was shortened to Ibalon. The word Bikol, which replaced Ibalon, was originally bikod (meaning "meandering"), a word which supposedly described the principal river of that area.

Archaeological diggings, dating back to as early as the Neolithic, and accidental findings resulting from the mining industry, road-building and railway projects in the region, reveal that the Bicol mainland is a rich storehouse of ceramic artifacts. Burial cave findings also point to the pre-Hispanic practice of using burial jars.

The Spanish influence in Bicol resulted mainly from the efforts of Augustinian and Franciscan Spanish missionaries. Through the Franciscans, the annual feast of the Virgin of Peñafrancia, the Patroness for Bicolandia, was started. Father Miguel Robles asked a local artist to carve a replica of the statue of the Virgin in Salamanca; now, the statue is celebrated through an annual fluvial parade in Naga City.

Bicolanos actively participated in the national resistance to the American and Japanese occupations through two well known leaders who rose up in arms: Simeón Ola and Governor Wenceslao Q. Vinzons.[4] Historically, the Bicolano people have been the most rebellious against foreign occupation.[4]

Area

Bicolanos live in Bicol Region that occupies the southeastern part of Luzon, now containing the provinces of Albay, Camarines Norte, Camarines Sur, Catanduanes and Sorsogon, as well as Masbate (although the majority of Masbate's population are a subgroup of Visayans). Many Bicolanos also live in the southeastern towns of the Calabarzon province of Quezon.

Demographics

Bicolanos number 6,299,283 in 2010.[5] They are descended from Austronesian peoples who came from Taiwan during the Iron Age. Many Bicolanos also have some Han Chinese and Spanish admixtures. Most of the townsfolk have small traces of each heritage while their language is referred to as Bicol/Bicolano. The Bicolano language is very fragmented, and its dialects are almost mutually incomprehensible to speakers of other Bicolano dialects. The majority of the Bicolano people are devout Roman Catholics and Catholic Mass is celebrated daily in many of the Bicol Region's churches.

Culture and traits

Cuisine

The Bicolano cuisine is primarily noted for the prominent use of chili peppers and gata (coconut milk) in its food. A classic example is the gulay na lada, known outside the region as Bicol Express, a well-loved dish using siling labuyo (native small chillies) and the aforementioned gata. Meals are generally rich in carbohydrates and viands of vegetables, fish, and meat are cooked in various ways. Bicolanos almost always cook their vegetables in coconut milk; for meat recipes such as pochero, adobo, and tapa. A special meat dish is the dinuguan. Fishes that serve as common viand are mackerel and anchovy; in Lake Buhi, the sinarapan or tabyos (known as the smallest fish in the world) is common.

Livelihood

Copra processing and abacá stripping are generally done by hand. Fishing is also an important industry and fish supply is normally plentiful during the months of May through September. Organized or big-time fishing makes use of costly nets and motor-powered and electric-lighted boats or launches called palakaya or basnigan. Individual fishermen, on the other hand, commonly use two types of nets – the basnig and the pangki as well as the chinchoro, buliche, and sarap. In Lake Buhi, the sarap and sumbiling are used; the small fishes caught through the former is the sinarapan. The bunuan (corral) of the inangcla, sakag, sibi-sibid and sakag types are common. The {{transl|bik|banwit{{transl|bik|, two kinds of which are the {{transl|bik|og-og{{transl|bik| and kitang, are also used. Mining and the manufacture of various items from abaca are important industries. The former started when the Spaniards discovered the Paracale mines in Camarines Norte.

Coconut and abacá are two dollar-earning products that are grown in the coastal valleys, hillsides, or slopes of several fertile volcanoes respectively. The Bicol River basin or rice granary provide the peasants rice, corn, and root crops for food and small cash surplus when crops evade the dreaded frequent typhoons. For land preparation, carabao-drawn plough and harrow are generally used; sickles are used for cutting rice stalks, threshing is done either by stepping on or beating the rice straws with basbas and cleaning is done with the use of the nigo (winnowing basket).

Cultural values

Like their other neighbouring regions, Bicolanas are also expected to lend a hand in household work. They are even anticipated to offer assistance after being married. On the other hand, Bicolano men are expected to assume the role of becoming the primary source of income and financial support of his family. Close family ties and religiosity are important traits for survival in the typhoon-prone physical environment. Some persisting traditional practices are the pamalay, pantomina and tigsikan. Beliefs on god, the soul and life after death are strongly held by the people. Related to these, there are annual rituals like the pabasa, tanggal, fiestas and flores de mayo. Side by side with these are held beliefs on spiritual beings as the tawo sa lipod, duwende, onglo, tambaluslos, kalag, katambay, aswang and mangkukulam.

On the whole, the value system of the Bicolanos shows the influence of Spanish religious doctrines and American materialism merged with traditional animistic beliefs. Consequently, it is a multi-cultural system that evolved through the years to accommodate the realities of the erratic regional climatic conditions in a varied geographical setting. Such traits can be gleaned from numerous folk tales and folk songs that abound, the most known of which is the Sarung Banggi. The heroic stories reflect such traits as kindness, a determination to conquer evil forces, resourcefulness and courage. The folk song come in the form of awit, sinamlampati, panayokyok, panambitan, hatol, pag-omaw, rawit-dawit and children’s song and chants.

To suit the tropical climate, Bicolanos use light material for their houses; others now have bungalows to withstand the impact of strong typhoons. Light, western-styled clothes are predominantly used now. The typical Bicolano wears light, western-styled clothes similar to the Filipinos in urban centres. Seldom, if ever, are there Bicolanos weaving {{transl|bik|sinamy{{transl|bik| or piña for clothing as in the past; sinamy is reserved now for pillow cases, mosquito nets, fishing nets, bags and other decorative items.[4]

Bicolanos observe an annual festival in honour of the Virgin of Peñafrancia every third Sunday of September. The towns of Naga comes alive. During the celebration, a jostling crowd of all-male devotees carries the image of the Virgin on their shoulders to the cathedral, while shouting Viva La Virgin! For the next seven days people, mostly Bicolanos, come for an annual visit light candles and kisses the image of the Virgin. To the Bicolanos, this affair is religious and cultural, as well. Every night, shows are held at the plaza the year's biggest cockfights take place, bicycle races are held and the river, a lively boat race precedes the fluvial procession. At noon of the third Saturday of the month, the devotees carry the Image on their shoulders preceded to the packed waterfront. The image is boarded onto the barge and the procession begins. With much splashing back to the old chapel until next year's celebration.[6]

Indigenous religion

Immortals

- Gugurang: the supreme god; causes the pit of Mayon volcano to rumble when he is displeased; cut Mt. Malinao in hald with a thunderbolt[7]; the god of good[8]

- Asuang: brother of Gugurang; an evil god who wanted Gugurang's fire, and gathered evil spirits and advisers to cause immortality and crime to reign; vanquished by Gugurang but his influence still lingers[9]

- Assistants of Gugurang

- Unnamed Giant: supports the world; movement from his index finger causes a small earthquake, while movement from his third finger causes strong ones; if he moves his whole body, the earth will be destroyed[12]

- Languiton: the god of the sky[13]

- Tubigan: the god of the water[14]

- Dagat: goddess of the sea[15]

- Paros: god of the wind; married to Dagat[16]

- Daga: son of Dagat and Paros; inherited his father'control of the wind; instigated an unsuccessfully rebellion against his grandfather, Languit, and died; his body became the earth[17]

- Adlao: son of Dagat and Paros; joined Daga's rebellion and died; his body became the sun[18]; in another myth, he was alive and during a battle, he cut one of Bulan's arm and hit Bulan's eyes, where the arm was flattened and became the earth, while Bulan's tears became the rivers and seas[19]

- Bulan: son of Dagat and Paros; joined Daga's rebellion and died; his body became the moon[20]; in another myth, he was alive and from his cut arm, the earth was established, and from his tears, the rivers and seas were established[21]

- Bitoon: daughter of Dagat and Paros; accidentally killed by Languit during a rage against his grandsons' rebellion; her shattered body became the stars[22]

- Unnamed God: a sun god who fell in love with the mortal, Rosa; refused to light the world until his father consented to their marriage; he afterwards visited Rosa, but forgetting to remove his powers over fire, he accidentally burned Rosa's whole village until nothing but hot springs remained[23]

- Magindang: the god of fishing who leads fishermen in getting a good fish catch through sounds and signs[24]

- Okot: the forest god whose whistle would lead hunters to their prey[25]

- Bakunawa: a serpent that seeks to swallow the moon[26]

- Haliya: the goddess of the moon[27]

- Batala: a good god who battled against Kalaon[28]

- Kalaon: an evil god of destruction[29]

- Son of Kalaon: son of Kalaon who defied his evil father's wishes[30]

- Onos: freed the great flood that changed the land's features[31]

- Oryol: a wily serpent who appeared as a beautiful maiden with a seductive voice; admired the hero Handyong's bravery and gallantry, leading her to aid the hero in clearing the region of beasts until peace came into the land[32]

Mortals

- Baltog: the hero who slew the giant wild boar Tandayag[33]

- Handyong: the hero who cleared the land of beasts with the aid of Oryol; crafted the people's first laws, which created a period for a variety of human inventions[34]

- Bantong: the hero who single-handedly slew the half-man half-beast Rabot[35]

- Dinahong: the first potter; a pygmy who taught the people how to cook and make pottery

- Ginantong: made the first plow, harrow, and other farming tools[36]

- Hablom: the inventor of the first weaving loom and bobbins[37]

- Kimantong: the first person to fashion the rudder called timon, the sail called layag, the plow called arado, the harrow called surod, the ganta and other measures, the roller, the yoke, the bolo, and the hoe[38]

- Sural: the first person to have thought of a syllabry; carved the first writing on a white rock-slab from Libong[39]

- Gapon: polished the rock-slab where the first writing was on[40]

- Takay: a lovely maiden who drowned during the great flood; transformed into the water hyacinth in Lake Bato[41]

- Rosa: a sun god's lover, who perished after the sun god accidentally burned her entire village[42]

See also

References

- "2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A: Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables) - Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 11, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Bicol - people". Britannica.com. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "The Bicolanos - National Commission for Culture and the Arts". Ncca.gov.ph. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A: Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables) - Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Herrington, Don. "Bicolanos Culture, Customs And Traditions - Culture And Tradition". Livinginthephilippines.com. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- Vibal, H. (1923). Asuang Steals Fire from Gugurang. Ethnography of The Bikol People, ii.

- Tiongson, N. G., Barrios, J. (1994). CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art: Peoples of the Philippines. Cultural Center of the Philippines.

- Vibal, H. (1923). Asuang Steals Fire from Gugurang. Ethnography of The Bikol People, ii.

- Vibal, H. (1923). Asuang Steals Fire from Gugurang. Ethnography of The Bikol People, ii.

- Vibal, H. (1923). Asuang Steals Fire from Gugurang. Ethnography of The Bikol People, ii.

- Beyer, H. O. (1923). Ethnogrphy of the Bikol People. vii.

- Beyer, H. O. (1923). Ethnogrphy of the Bikol People. vii.

- Beyer, H. O. (1923). Ethnogrphy of the Bikol People. vii.

- Beyer, H. O. (1923). Ethnogrphy of the Bikol People. vii.

- Beyer, H. O. (1923). Ethnogrphy of the Bikol People. vii.

- Beyer, H. O. (1923). Ethnogrphy of the Bikol People. vii.

- Beyer, H. O. (1923). Ethnogrphy of the Bikol People. vii.

- Arcilla, A. M. (1923). The Origin of Earth and of Man. Ethnography of the Bikol People, vii.

- Beyer, H. O. (1923). Ethnogrphy of the Bikol People. vii.

- Arcilla, A. M. (1923). The Origin of Earth and of Man. Ethnography of the Bikol People, vii.

- Beyer, H. O. (1923). Ethnogrphy of the Bikol People. vii.

- Buenabora, N. P. (1975). Pag-aaral at Pagsalin sa Pilipino ng mga Kaalamang-Bayan ng Bikol at ang Kahalagahan ng mga Ito sa Pagtuturo ng Pilipino sa Bagong Lipunan. National Teacher's College.

- Realubit, M. L. F. (1983). Bikols of the Philippines. A.M.S. Press.

- Realubit, M. L. F. (1983). Bikols of the Philippines. A.M.S. Press.

- Realubit, M. L. F. (1983). Bikols of the Philippines. A.M.S. Press.

- Tiongson, N. G., Barrios, J. (1994). CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art: Peoples of the Philippines. Cultural Center of the Philippines.

- Realubit, M. L. F. (1983). Bikols of the Philippines. A.M.S. Press.

- Realubit, M. L. F. (1983). Bikols of the Philippines. A.M.S. Press.

- Realubit, M. L. F. (1983). Bikols of the Philippines. A.M.S. Press.

- Castaño, F. J. (1895). un pequeño fragmento inedito en verso.

- Castaño, F. J. (1895). un pequeño fragmento inedito en verso.

- Castaño, F. J. (1895). un pequeño fragmento inedito en verso.

- Castaño, F. J. (1895). un pequeño fragmento inedito en verso.

- Castaño, F. J. (1895). un pequeño fragmento inedito en verso.

- Lacson, T.; Gamos, A. (1992). Ibalon: Tatlong Bayani ng Epikong Bicol. Philippines: Children's Communication Center: Aklat Adarna.

- Aguilar, [edited by] Celedonio G. (1994). Readings in Philippine literature. Manila: Rex Book Store.

- Aguilar, [edited by] Celedonio G. (1994). Readings in Philippine literature. Manila: Rex Book Store.

- Aguilar, [edited by] Celedonio G. (1994). Readings in Philippine literature. Manila: Rex Book Store.

- Aguilar, [edited by] Celedonio G. (1994). Readings in Philippine literature. Manila: Rex Book Store.

- Aguilar, [edited by] Celedonio G. (1994). Readings in Philippine literature. Manila: Rex Book Store.

- Buenabora, N. P. (1975). Pag-aaral at Pagsalin sa Pilipino ng mga Kaalamang-Bayan ng Bikol at ang Kahalagahan ng mga Ito sa Pagtuturo ng Pilipino sa Bagong Lipunan. National Teacher's College.

External links

- "BICOL STANDARD - Bicol News". Bicolstandard.com. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Bicolano Social Network - goBicol.com". GoBicol.com. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Ang Aming Angkan". Ang Aming Angkan. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2018.